AI Blakface controversy erupts as Bush Legend TikTok star is revealed to be entirely fabricated

3 Sources

3 Sources

[1]

This TikTok star sharing Australian animal stories doesn't exist - it's AI Blakface

The self-described "Bush Legend" on TikTok, Facebook and Instagram is growing in popularity. These short and sharp videos feature an Aboriginal man - sometimes painted up in ochre, other times in an all khaki outfit - as he introduces different native animals and facts about them. These videos are paired with miscellaneous yidaki (didgeridoo) tunes, including techno mixes. Comments on the videos often mention his bubbly persona, with some comments saying he needs his own TV show. But the Bush Legend isn't real. He is generated by artificial intelligence (AI). This is a part of a growing influx of AI being utilised to represent Indigenous peoples, knowledges and cultures with no community accountability or relationships with Indigenous peoples. It forms a new type of cultural appropriation, one that Indigenous peoples are increasingly concerned about. Do they know it's AI? In the user description, the Bush Legend pages say the visuals are AI. But does the average user scrolling through videos on their social media click onto a profile to read these details? Some of the videos do feature AI watermarks, or mention they are AI in the caption. But many in the audience will be completely unaware this person is not real, and the entire video is artificially generated. These videos "bait" the audience in through a spectrum of cute and cuddly to extremely dangerous creatures. Comments left on the videos query how close the man is to the animals, alongside their words of encouragement. One commenter on Facebook writes "You have the same wonderful energy Steve Irwin had and your voice is great to listen to." The voice and energy they are referring to is fabricated. A lack of respect With any Indigenous content on the internet (authentic or AI), there remains racist commentary. As Indigenous people, we often say don't read the comments, when it comes to social media and Indigenous content. While the Bush Legend is not real nor culturally grounded, it too is not immune to online racism. I have read comments on his videos which uplift this AI persona while denigrating all other Indigenous people. While this does not impact the creator, it does impact Indigenous peoples who are reading the comments. The only information available on Bush Legend, other than the fact it is AI, is the creator is based in Aotearoa New Zealand. This suggests there is likely no connection to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities that this likeness is being taken from. Recently, Bush Legend addressed some of this critique in a video. He said: I'm not here to represent any culture or group [...] If this isn't your thing, mate, no worries at all, just scroll and move on. This does not sufficiently address the very real concerns. If the videos are "simply about animal stories", why does the creator insist on using the likeness of an Aboriginal man? Accountability to the communities this involves is not considered in this scenario. The ethics of AI Generative AI represents a new platform in which Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) rights are breached. Concerns for AI and Indigenous peoples lie across many areas, including education, and the lack of Indigenous involvement in AI creation and governance. Of course, there is also the cost to Country with considerable environmental impacts. The recently released national AI plan offers little in terms of regulation. Indigenous peoples have long fought to tell our own stories. AI poses another way in which our self determination is diminished or removed completely. It also serves as a way for non-Indigenous people to distance themselves from actual Indigenous peoples by allowing them to engage with content which is fabricated and, often, more palatable. Bush Legend reflects a slippery slope when it comes to AI generated content of Indigenous peoples, as people can remove themselves further and further from engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people directly. A new era of AI Blakface We are seeing the rise of an AI Blakface that is utilised with ease thanks to the availability and prevalence of AI. Non-Indigenous people and entities are able to create Indigenous personas through AI, often grounded in stereotypical representations that both amalgamate and appropriate cultures. Bush Legend is often seen wearing cultural jewellery and with ochre painted on his skin. As these are generated, they are shallow misappropriations and lack the necessary cultural underpinnings of these practices. This forms a new type of appropriation, that extends on the violence that Indigenous peoples already experience in the digital realm, particularly on social media. The theft of Indigenous knowledge for generative AI forms a new type of algorithmic settler colonialism, impacting Indigenous self-determination. Most concerningly, these AI Blakfaces can be monetised and lead to financial gain for the creator. This financial benefit should go to the communities the content is taking from. What is needed? It is concerning to be living in a time where we do not know if the things we are consuming online are real. Increasing our AI and media literacy levels is integral. Seeing AI content shared online as truth? Let the person sharing this content know - conversations with our communities serve as an opportunity to learn together. Support actual Indigenous people sharing knowledge online, such as @Indigigrow, @littleredwrites or @meissa. Or check out all the Indigenous Ranger videos on TikTok. When engaging online, take a moment to consider the source. Is this AI generated? Is this where my support should be?

[2]

Indigenous TikTok star 'Bush Legend' is actually AI-generated, leading to accusations of 'digital blackface'

These short and sharp videos feature an Aboriginal man -- sometimes painted up in ochre, other times in an all khaki outfit -- as he introduces different native animals and facts about them. These videos are paired with miscellaneous yidaki (didgeridoo) tunes, including techno mixes. Comments on the videos often mention his bubbly persona, with some comments saying he needs his own TV show. But the Bush Legend isn't real. He is generated by artificial intelligence (AI). This is a part of a growing influx of AI being utilized to represent Indigenous peoples, knowledges and cultures with no community accountability or relationships with Indigenous peoples. It forms a new type of cultural appropriation, one that Indigenous peoples are increasingly concerned about. In the user description, the Bush Legend pages say the visuals are AI. But does the average user scrolling through videos on their social media click onto a profile to read these details? Some of the videos do feature AI watermarks, or mention they are AI in the caption. But many in the audience will be completely unaware this person is not real, and the entire video is artificially generated. These videos "bait" the audience in through a spectrum of cute and cuddly to extremely dangerous creatures. Comments left on the videos query how close the man is to the animals, alongside their words of encouragement. One commenter on Facebook writes "You have the same wonderful energy Steve Irwin had and your voice is great to listen to." The voice and energy they are referring to is fabricated. With any Indigenous content on the internet (authentic or AI), there remains racist commentary. As Indigenous people, we often say don't read the comments, when it comes to social media and Indigenous content. While the Bush Legend is not real nor culturally grounded, it too is not immune to online racism. I have read comments on his videos which uplift this AI persona while denigrating all other Indigenous people. While this does not impact the creator, it does impact Indigenous peoples who are reading the comments. The only information available on Bush Legend, other than the fact it is AI, is the creator is based in Aotearoa New Zealand. This suggests there is likely no connection to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities that this likeness is being taken from. I'm not here to represent any culture or group [...] If this isn't your thing, mate, no worries at all, just scroll and move on. This does not sufficiently address the very real concerns. If the videos are "simply about animal stories", why does the creator insist on using the likeness of an Aboriginal man? Accountability to the communities this involves is not considered in this scenario. Generative AI represents a new platform in which Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) rights are breached. Concerns for AI and Indigenous peoples lie across many areas, including education, and the lack of Indigenous involvement in AI creation and governance. Of course, there is also the cost to Country with considerable environmental impacts. The recently released national AI plan offers little in terms of regulation. Indigenous peoples have long fought to tell our own stories. AI poses another way in which our self determination is diminished or removed completely. It also serves as a way for non-Indigenous people to distance themselves from actual Indigenous peoples by allowing them to engage with content which is fabricated and, often, more palatable. Bush Legend reflects a slippery slope when it comes to AI generated content of Indigenous peoples, as people can remove themselves further and further from engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people directly. Non-Indigenous people and entities are able to create Indigenous personas through AI, often grounded in stereotypical representations that both amalgamate and appropriate cultures. Bush Legend is often seen wearing cultural jewelry and with ochre painted on his skin. As these are generated, they are shallow misappropriations and lack the necessary cultural underpinnings of these practices. This forms a new type of appropriation, that extends on the violence that Indigenous peoples already experience in the digital realm, particularly on social media. The theft of Indigenous knowledge for generative AI forms a new type of algorithmic settler colonialism, impacting Indigenous self-determination. Most concerningly, these AI Blakfaces can be monetized and lead to financial gain for the creator. This financial benefit should go to the communities the content is taking from. It is concerning to be living in a time where we do not know if the things we are consuming online are real. Increasing our AI and media literacy levels is integral. Seeing AI content shared online as truth? Let the person sharing this content know -- conversations with our communities serve as an opportunity to learn together. Support actual Indigenous people sharing knowledge online, such as @Indigigrow, @littleredwrites or @meissa. Or check out all the Indigenous Ranger videos on TikTok. When engaging online, take a moment to consider the source. Is this AI generated? Is this where my support should be?

[3]

'It's AI blackface': social media account hailed as the Aboriginal Steve Irwin is an AI character created in New Zealand

More than 180,000 people follow the Bush Legend's accounts across Meta platforms, but its Aboriginal host is a work of digital fiction With a mop of dark curls and brown eyes, Jarren stands in the thick of the Australian outback, red dirt at his feet, a snake unfurling in front of him. In a series of online videos, the social media star, known online as the Bush Legend, walks through dense forests or drives along deserted roads on the hunt for wedge-tailed eagles. Many of the videos are set to pulsating percussion instruments and yidakis (didgeridoo). His voice sounds like a cross between Gardening Australia's Costa Georgiadis and Steve Irwin. His speech is peppered with "mate" and "crikey" as he passionately shares snippets with thousands of his followers about Australian wildlife - from venomous snakes and crocodiles to redback spiders and the elusive night parrots, once thought extinct. His followers leave admiring comments, marvelling at how he can get so close to the animals and even suggesting he needs his own TV show. But none of it is real. The wildlife and the man presenting them are all creations of AI. Created in October 2025, Meta indicates the account is based in New Zealand, with the Instagram account originally sharing an AI-generated satirical news account called 'Nek Minute News before pivoting to wildlife content. Earlier incarnations of Bush Legend show the character wearing white body paint seeming to mimic ochre, a beaded necklace adorning his neck. As of this week, the Bush Legend account has 90,000 followers on Instagram and 96,000 on Facebook. It says its focus is on building awareness and education about Australian wildlife. Guardian Australia has contacted the person believed to have created the account, who is a South African living in New Zealand. They did not respond to multiple approaches. The choice to create an avatar of an Indigenous person has raised ethical concerns. Dr Terri Janke, a lawyer and Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, expert, says the images and content are "remarkable" in their realism. "You think it's real, I was just scrolling through and I was like, 'How come I've never heard of this guy?' He's deadly, he should have his own show," she says. "Is he the Black Steve Irwin? In his greens or the khakis, he's a bit like Steve Irwin meets David Attenborough. But while the Wuthathi, Yadhaigana and Meriam woman says the engaging videos are "pretty incredible when you look at it as a tool for education", the creation of a seemingly Indigenous avatar is offensive and carries a risk of "cultural flattening". "Whose personal image did they use to make this person? Did they bring together people?" she asks. "I feel a bit misled by it all." AI-generated content poses a particular risk to marginalised communities and could be considered theft of cultural and intellectual property. It also potentially takes opportunities away from authentic accounts, such as videos created by the vast network of Aboriginal rangers. "It's theft that is very insidious in that it also involves a cultural harm," Janke says. "Because of the discrimination ... the impacts of stereotypes and negative thinking, those impacts do hit harder." Janke says it is possible to ethically use AI technology to create content about First Nations people, but it requires the consent and involvement of First Nations people. Tamika Worrell, a senior lecturer in critical Indigenous studies at Macquarie University, says the AI avatar is a form of cultural appropriation and "digital blackface" where a non-Black person creates a Black or Indigenous caricature online. The Kamilaroi woman says the proliferation of AI tools without appropriate legislative guardrails means that images, cultural knowledge and stories can be transmitted without appropriate consent. "AI becomes this new platform that we have no control or no say in it," she says. "Not only stories or language but actual visuals of us can often be taken from people that have passed away - or just blending a range of different people [to create an AI avatar] with no kind of accountability to the communities that these people are from. "It's AI blackface - people can just generate artworks, generate people, [but] they are not actually engaging with Indigenous people." The potential for harm is twofold: such accounts default to sharing the "palatable" or "comfortable" aspects of Indigenous cultural knowledge and experience, rather than the more complex reality; and it also has the potential to amplify racism. "I was looking at the comments from a latest post of Bush Legend. We see the same racist comments that we know mob online get. We see it again applied to an AI person as well," she says. Toby Walsh, laureate fellow and scientia professor of artificial intelligence at the University of New South Wales, says AI is trained to reproduce information and rendering through large-scale data sets with inbuilt biases, meaning it's not immune to racist or prejudicial content. "They are going to carry the biases of that training data," he says. "Certain groups may be stereotyped because the video data or the image data that exists in that group online is somewhat stereotypical. So we're going to perpetuate that stereotype moving forwards." Guardian Australia attempted to contact the page's creator through multiple social media accounts and email but was yet to receive a response. The Bush Legend account has seemingly addressed the criticism through its avatar, saying the page doesn't seek to "represent any culture or group". "This channel is simply about animal stories," the AI creation said in a video last week. It went on to say the page "isn't asking for money, donations or support" and content is "free to watch", and suggests people "scroll on" if they don't like it. Earlier plugs asked followers to subscribe for $2.99 per month. Meta has been contacted for further comment. Walsh says while digital literacy can assist users with identifying AI content, the "tells" that help identify it are getting increasingly hard to spot. "If not now, in the very near future, it's going to be next to impossible to be able to identify for yourself whether this was real or fake," Walsh says. "We used to believe in things that we see, because it used to be the things that you saw were largely real things. "Now it's not hard to fake stuff. It's incredibly easy to fake stuff in a very convincing way, so we're going to stretch the boundaries of what is true and false."

Share

Share

Copy Link

A popular social media personality known as Bush Legend, who shares Australian animal stories and has amassed over 180,000 followers, has been exposed as an AI-generated persona created in New Zealand. Indigenous experts are calling it AI Blakface and cultural appropriation, raising concerns about how artificial intelligence enables the theft of Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property without community accountability or consent.

AI-Generated TikTok Persona Deceives Thousands

A self-described "Bush Legend" has been captivating audiences across TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram with short videos featuring what appears to be an Aboriginal man sharing Australian animal stories. The character, sometimes painted in ochre and other times dressed in khaki, introduces native wildlife—from venomous snakes to wedge-tailed eagles—set to yidaki (didgeridoo) tunes and techno mixes

1

. With over 90,000 followers on Instagram and 96,000 on Facebook, the account has drawn comparisons to Steve Irwin, with one commenter writing, "You have the same wonderful energy Steve Irwin had and your voice is great to listen to"2

. But the bubbly persona they're praising doesn't exist. Bush Legend is entirely AI-generated content, created by someone based in New Zealand with no apparent connection to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities3

.

Source: The Conversation

Digital Blackface and Cultural Appropriation

While the user description mentions the visuals are generated by artificial intelligence, many viewers remain unaware they're watching fabricated content. Some videos feature AI watermarks, but most audience members scrolling through social media don't click onto profiles to read these details

1

. Indigenous experts are calling this phenomenon AI Blakface—a form of digital blackface where non-Indigenous creators use generative AI to produce Indigenous personas grounded in stereotypical representations. Dr. Terri Janke, a Wuthathi, Yadhaigana and Meriam woman and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property expert, describes feeling "misled" by the realistic images. "Whose personal image did they use to make this person?" she asks, noting concerns about cultural flattening and the potential theft of ICIP rights3

. The character appears wearing cultural jewelry and ochre body paint—sacred practices that lack necessary cultural underpinnings when artificially generated, creating shallow misappropriation1

.Algorithmic Settler Colonialism and Self-Determination

Tamika Worrell, a Kamilaroi woman and senior lecturer in critical Indigenous studies at Macquarie University, explains that AI becomes a platform where Indigenous peoples have no control or say. "It's AI blackface—people can just generate artworks, generate people, [but] they are not actually engaging with Indigenous people," she states

3

. This represents what experts call algorithmic settler colonialism, a new form of appropriation that diminishes Indigenous self-determination by allowing non-Indigenous people to distance themselves from actual Indigenous peoples. The creator, believed to be a South African living in New Zealand, addressed criticism in a video saying, "I'm not here to represent any culture or group," but offered no explanation for why the likeness of an Aboriginal man was necessary if the content is "simply about animal stories"1

. Community accountability to the communities this involves remains absent.Monetization Without Consent

The ethical concerns extend beyond representation. These AI-generated personas can be monetized, leading to financial gain for creators while potentially taking opportunities away from authentic accounts, such as videos created by Aboriginal rangers

3

. The theft of Indigenous knowledge for generative AI creates a troubling precedent where financial benefits flow to creators rather than the communities whose cultural practices are being appropriated. Meta indicates the account originally shared AI-generated satirical news before pivoting to wildlife content, with earlier versions showing the character wearing white body paint mimicking ochre and beaded necklaces3

.Related Stories

Amplifying Racism and Stereotypes

The harm extends to the comment sections on social media platforms. While Bush Legend may not be real, the racist commentary it attracts is. Worrell notes that the AI persona receives the same racist comments that Indigenous people experience online, with some comments uplifting the AI character while denigrating actual Indigenous peoples

3

. This creates a disturbing dynamic where audiences engage with palatable, fabricated Indigenous content while avoiding the complex realities of First Nations communities. The lack of Indigenous involvement in AI creation and governance, combined with minimal regulation in recently released national AI plans, leaves communities vulnerable to these stereotypes and misappropriation1

.The Need for Media Literacy and Ethics

As AI-generated content becomes increasingly realistic, the need for media literacy grows urgent. Dr. Janke acknowledges that while the technology could serve as an incredible educational tool, ethical use requires consent and involvement of First Nations people

3

. Indigenous peoples have long fought to tell their own stories, and artificial intelligence poses another threat to that self-determination. The Bush Legend case highlights how easily non-Indigenous entities can create Indigenous personas through AI, removing themselves further from engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people directly2

. Experts urge audiences to question content authenticity and engage in conversations with their communities when they see AI content shared as truth, building collective awareness about this emerging form of cultural harm.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[2]

Related Stories

AI-Generated 'Australiana' Images Reveal Racial and Cultural Biases, Study Finds

15 Aug 2025•Technology

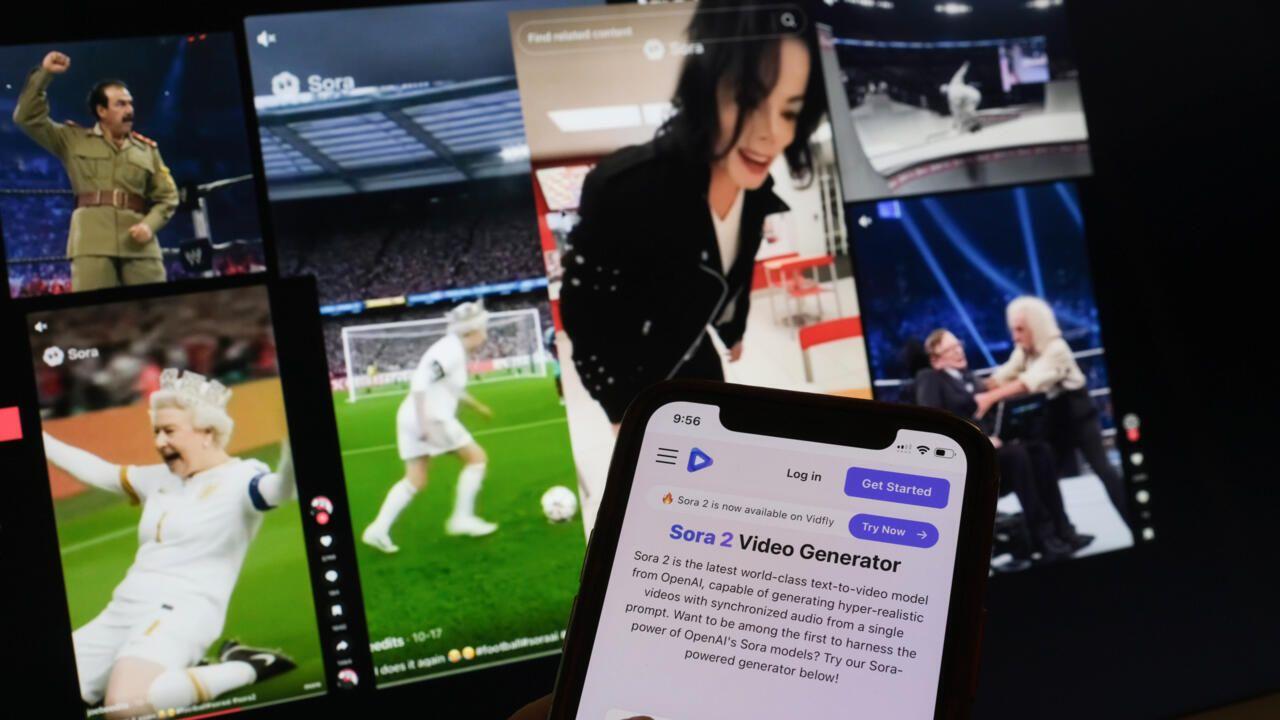

Sora 2: OpenAI's AI Video Generator Sparks Controversy and Ethical Concerns

14 Oct 2025•Technology

AI-Generated Country Hit 'Walk My Walk' Sparks Ethics Debate Over Artist Attribution and Voice Cloning

29 Nov 2025•Entertainment and Society

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic sues Pentagon over supply chain risk label after refusing autonomous weapons use

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round as questions swirl around AI bubble and profitability

Business and Economy