AI Chatbots Sway Voters More Effectively Than Traditional Political Ads, New Studies Reveal

18 Sources

18 Sources

[1]

AI chatbots can persuade voters to change their minds

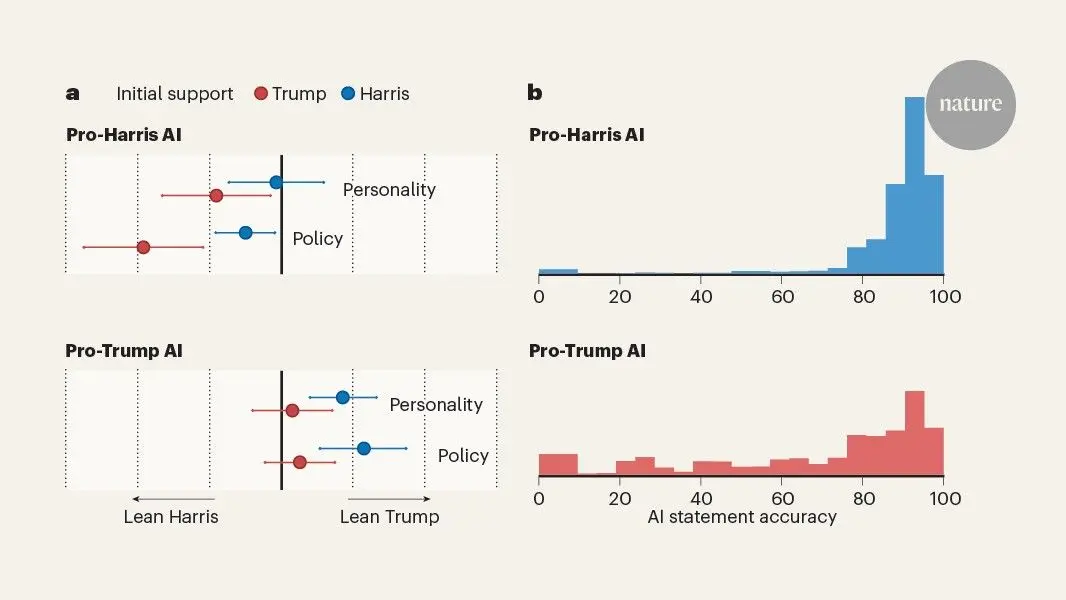

You have full access to this article via Jozef Stefan Institute. The world is getting used to 'talking' to machines. Technology that just months ago seemed improbable or marginal has erupted quickly into the everyday lives of millions, perhaps billions, of people. Generative conversational artificial-intelligence systems, such as OpenAI's ChatGPT, are being used to optimize tasks, plan holidays and seek advice on matters ranging from the trivial to the existential -- a quiet exchange of words that is shaping how decisions are made. Against this backdrop, the urgent question is: can the same conversational skills that make AI into helpful assistants also turn them into powerful political actors? In a pair of studies in Nature and Science, researchers show that dialogues with large language models (LLMs) can shift people's attitudes towards political candidates and policy issues. The researchers also identify which features of conversational AI systems make them persuasive, and what risks they might pose for democracy. Political scientists have long debated whether election campaigns have the power to change minds. The answer to this question depends on the specifics of what is being investigated, but a realistic estimate is that political advertising shifts vote choices by less than one percentage point. Although such modest shifts can matter a great deal in close races, findings from Lin et al. and Hackenburg et al. suggest that AI-driven persuasion operates on a different scale. Lin and colleagues report the results of a controlled experiment in which more than 2,300 participants in the United States chatted with an AI model that tried to convince them to support either Kamala Harris or Donald Trump in the 2024 US presidential election (Fig. 1a). Participants exchanged three rounds of messages with the model, which was instructed to remain respectful and fact-based while tailoring its arguments to each participant's stated political preferences. Similar experiments were run in Massachusetts on a ballot initiative to legalize psychedelic drugs, and later in Canada and Poland around their 2025 national elections. The effects were striking. Conversations favouring one candidate increased support for that candidate by around 2-3 points on a scale of 0-100, which is larger than the average effect of political advertising. Persuasion was stronger when the chat focused on policy issues rather than the candidate's personality, and when the AI provided specific evidence or examples. Importantly, roughly one-third of the effect persisted when participants were contacted a month later, going against the intuitive critique that the initial shifts were probably volatile and ultimately inconsequential. The persuasive influence was also asymmetric: AI chatbots were more successful at persuading 'out-party' participants (that is, those who initially opposed the targeted candidate) than at mobilizing existing supporters. In the state-level ballot-measure experiment in Massachusetts, persuasion effects were even larger, reaching double digits on the 0-100 scale. Why were chatbots so effective? Analysing 27 rhetorical strategies used by the AI models to persuade voters who engaged with them, the team found that supplying factual information was one of the strongest predictors of success. Strategies such as attempts to pre-empt objections, emotional appeals or explicit calls to vote were less used, and less persuasive. Yet 'facts' were not always factual. When the team fact-checked thousands of statements produced by the AI models, they found that most were accurate, but not all. Across countries and language models, claims made by AI chatbots that promoted right-leaning candidates were substantially more inaccurate than claims advocating for left-leaning ones (Fig. 1b). These findings carry the uncomfortable implication that political persuasion by AI tools can exploit imbalances in what the models 'know', spreading uneven inaccuracies even under explicit instructions to remain truthful. Hackenburg et al. broaden these results. The researchers engaged nearly 77,000 participants in more than 91,000 AI-human conversations over stances on 707 political issues. They compared 19 LLMs, ranging from small open-source systems to state-of-the-art proprietary models such as OpenAI's GPT-4o and xAI's Grok-3. Bigger models were more persuasive. For every tenfold increase in the model's computing power, its persuasive abilities rose by about 1.6 percentage points. However, post-training interventions -- such as supervised fine-tuning to boost the models' capacities to mimic effective persuasion, or using a model to predict what the most persuasive response would be -- mattered even more. Models that were fine-tuned specifically for persuasion were up to 50% more effective than their untuned counterparts. Hackenburg and colleagues analysed a maximally persuasive configuration that 'pulls all the levers at once', including personalizing messages. They estimated that it could shift opinions by 16 points on average and 26 points among participants who initially disagreed with a given issue. However, there was a catch: the same settings also reduced factual accuracy. Notably, information-dense models were the most convincing, but also the most error-prone. Persuasion and accuracy, it seems, trade off against each other. It is important to note that these findings come from controlled online experiments. It is unclear how such persuasive effects would play out in real political environments in which exposure to persuasive AI agents is (often) voluntary and conscious. Such environments also contain a myriad of contrasting messages competing for attention, and users can ultimately decide to avoid or ignore specific information sources. Nevertheless, these studies provide compelling systematic evidence that conversational AI systems hold the power, or at least the potential, to shape political attitudes across diverse contexts. The ability to respond to users conversationally could make such systems uniquely powerful political actors, much more influential than conventional campaign media. At the same time, the results highlight that inaccuracy seems to be a crucial downside. The AI models in these experiments were instructed to remain factual, and still produced distortions. In real-world use, where incentives might favour engagement rather than truth, the line between effective persuasion and misinformation could blur further. The broader implication is clear: persuasion is no longer a uniquely 'human' business. As AI systems become embedded in chat platforms, virtual assistants and social-media feeds, political dialogue between voters and machines could be an increasing occurrence. Crucially, if conversation with AI can move opinions more than most campaign tools can, there is a fundamental question that will need substantive answers from a legal, ethical and philosophical standpoint: who controls this capacity? Regulations should address not only what AI systems say, but also how they are trained and optimized. Transparency about post-training objectives, disclosure when users are conversing with AI and limits on political outreach will probably become essential components of future campaign regulation. Finally, and perhaps optimistically, these experiments offer insights that extend beyond AI, pointing at the state of political discourse in general. People were most persuadable when the AI reasoned politely and spoke in evidence-based terms -- qualities that are often seen as lacking in human political debate. And although the chatbots were instructed to be civil and seemed to comply with the injunction -- something much less likely to occur in the real world -- a hopeful lesson is that civility and facts still matter. At least when they are delivered by a machine.

[2]

Researchers find what makes AI chatbots politically persuasive

Roughly two years ago, Sam Altman tweeted that AI systems would be capable of superhuman persuasion well before achieving general intelligence -- a prediction that raised concerns about the influence AI could have over democratic elections. To see if conversational large language models can really sway political views of the public, scientists at the UK AI Security Institute, MIT, Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, and many other institutions performed by far the largest study on AI persuasiveness to date, involving nearly 80,000 participants in the UK. It turned out political AI chatbots fell far short of superhuman persuasiveness, but the study raises some more nuanced issues about our interactions with AI. AI dystopias The public debate about the impact AI has on politics has largely revolved around notions drawn from dystopian sci-fi. Large language models have access to essentially every fact and story ever published about any issue or candidate. They have processed information from books on psychology, negotiations, and human manipulation. They can rely on absurdly high computing power in huge data centers worldwide. On top of that, they can often access tons of personal information about individual users thanks to hundreds upon hundreds of online interactions at their disposal. Talking to a powerful AI system is basically interacting with an intelligence that knows everything about everything, as well as almost everything about you. When viewed this way, LLMs can indeed appear kind of scary. The goal of this new gargantuan AI persuasiveness study was to break such scary visions down into their constituent pieces and see if they actually hold water. The team examined 19 LLMs, including the most powerful ones like three different versions of ChatGPT and xAI's Grok-3 beta, along with a range of smaller, open source models. The AIs were asked to advocate for or against specific stances on 707 political issues selected by the team. The advocacy was done by engaging in short conversations with paid participants enlisted through a crowdsourcing platform. Each participant had to rate their agreement with a specific stance on an assigned political issue on a scale from 1 to 100 both before and after talking to the AI. Scientists measured persuasiveness as the difference between the before and after agreement ratings. A control group had conversations on the same issue with the same AI models -- but those models were not asked to persuade them. "We didn't just want to test how persuasive the AI was -- we also wanted to see what makes it persuasive," says Chris Summerfield, a research director at the UK AI Security Institute and co-author of the study. As the researchers tested various persuasion strategies, the idea of AIs having "superhuman persuasion" skills crumbled. Persuasion levers The first pillar to crack was the notion that persuasiveness should increase with the scale of the model. It turned out that huge AI systems like ChatGPT or Grok-3 beta do have an edge over small-scale models, but that edge is relatively tiny. The factor that proved more important than scale was the kind of post-training AI models received. It was more effective to have the models learn from a limited database of successful persuasion dialogues and have them mimic the patterns extracted from them. This worked far better than adding billions of parameters and sheer computing power. This approach could be combined with reward modeling, where a separate AI scored candidate replies for their persuasiveness and selected the top-scoring one to give to the user. When the two were used together, the gap between large-scale and small-scale models was essentially closed. "With persuasion post-training like this we matched the Chat GPT-4o persuasion performance with a model we trained on a laptop," says Kobi Hackenburg, a researcher at the UK AI Security Institute and co-author of the study. The next dystopian idea to fall was the power of using personal data. To this end, the team compared the persuasion scores achieved when models were given information about the participants' political views beforehand and when they lacked this data. Going one step further, scientists also tested whether persuasiveness increased when the AI knew the participants' gender, age, political ideology, or party affiliation. Just like with model scale, the effects of personalized messaging created based on such data were measurable but very small. Finally, the last idea that didn't hold up was AI's potential mastery of using advanced psychological manipulation tactics. Scientists explicitly prompted the AIs to use techniques like moral reframing, where you present your arguments using the audience's own moral values. They also tried deep canvassing, where you hold extended empathetic conversations with people to nudge them to reflect on and eventually shift their views. The resulting persuasiveness was compared with that achieved when the same models were prompted to use facts and evidence to back their claims or just to be as persuasive as they could without specifying any persuasion methods to use. I turned out using lots of facts and evidence was the clear winner, and came in just slightly ahead of the baseline approach where persuasion strategy was not specified. Using all sorts of psychological trickery actually made the performance significantly worse. Overall, AI models changed the participants' agreement ratings by 9.4 percent on average compared to the control group. The best performing mainstream AI model was Chat GPT 4o, which scored nearly 12 percent followed by GPT 4.5 with 10.51 percent, and Grok-3 with 9.05 percent. For context, static political ads like written manifestos had a persuasion effect of roughly 6.1 percent. The conversational AIs were roughly 40-50 percent more convincing than these ads, but that's hardly "superhuman." While the study managed to undercut some of the common dystopian AI concerns, it highlighted a few new issues. Convincing inaccuracies While the winning "facts and evidence" strategy looked good at first, the AIs had some issues with implementing it. When the team noticed that increasing the information density of dialogues made the AIs more persuasive, they started prompting the models to increase it further. They noticed that, as the AIs used more factual statements, they also became less accurate -- they basically started misrepresenting things or making stuff up more often. Hackenburg and his colleagues note that we can't say if the effect we see here is causation or correlation -- whether the AIs are becoming more convincing because they misrepresent the facts or whether spitting out inaccurate statements is a byproduct of asking them to make more factual statements. The finding that the computing power needed to make an AI model politically persuasive is relatively low is also a mixed bag. It pushes back against the vision that only a handful of powerful actors will have access to a persuasive AI that can potentially sway public opinion in their favor. At the same time, the realization that everybody can run an AI like that on a laptop creates its own concerns. "Persuasion is a route to power and influence -- it's what we do when we want to win elections or broke a multi-million-dollar deal," Summerfield says. "But many forms of misuse of AI might involve persuasion. Think about fraud or scams, radicalization, or grooming. All these involve persuasion." But perhaps the most important question mark in the study is the motivation behind the rather high participant engagement, which was needed for the high persuasion scores. After all, even the most persuasive AI can't move you when you just close the chat window. People in Hackenburg's experiments were told that they would be talking to the AI and that the AI would try to persuade them. To get paid, a participant only had to go through two turns of dialogue (they were limited to no more than 10). The average conversation length was seven turns, which seemed a bit surprising given how far beyond the minimum requirement most people went. Most people just roll their eyes and disconnect when they realize they are talking with a chatbot. Would Hackenburg's study participants remain so eager to engage in political disputes with random chatbots on the Internet in their free time if there was no money on the table? "It's unclear how our results would generalize to a real-world context," Hackenburg says.

[3]

AI chatbots can sway voters with remarkable ease -- is it time to worry?

Artificial-intelligence chatbots can influence voters in major elections -- and have a bigger effect on people's political views than conventional campaigning and advertising. A study published today in Nature found that participants' preferences in real-world elections swung by up to 15 percentage points after conversing with a chatbot. In a related paper published in Science, researchers showed that these chatbots' effectiveness stems from their ability to synthesize a lot of information in a conversational way. The findings showcase the persuasive power of chatbots, which are used by more than one hundred million users each day, says David Rand, an author of both studies and a cognitive scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Both papers found that chatbots influence voter opinions not by using emotional appeals or storytelling, but by flooding the user with information. The more information the chatbots provided, the more persuasive they were -- but they were also more likely to produce false statements, the authors found. This can make AI into "a very dangerous thing", says Lisa Argyle, a computational social scientist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. "Instead of people becoming more informed, it's people becoming more misinformed." The studies have an "impressive scope", she adds. "The scale at which they've studied everything is so far beyond what's normally done in social sciences." The rapid adoption of chatbots since they went mainstream in 2023 has sparked concern over their potential to manipulate public opinion. To understand how persuasive AI can be when it comes to political beliefs, researchers asked nearly 6,000 participants from three countries -- Canada, Poland and the United States -- to rate their preferences for specific candidates in their country's leadership elections that took place over the past year on a 0-to-100 scale. Next, the researchers randomly assigned participants to have a back-and-forth conversation with a chatbot that was designed to support a particular politician. After this dialogue, participants once again rated their opinion on that candidate. More than 2,300 participants in the United States completed this experiment ahead of the 2024 election between President Donald Trump and former vice-president Kamala Harris. When the candidate the AI chatbot was designed to advocate for differed from the participant's initial preference, the person's ratings shifted towards that candidate by two to four points. Previous research has found that people's views typically shift by less than one point after viewing conventional political adverts. This effect was much more pronounced for participants in Canada and Poland, who completed the experiment before their countries' elections earlier this year: their preferences towards the candidates shifted by an average of about ten points after talking to the chatbot. Rand says he was "totally flabbergasted" by the size of this effect. He adds that the chatbots' influence might have been weaker in the United States because of the politically polarized environment, in which people already have strong assumptions and feelings towards the candidates. In all countries, the chatbots that focused on candidates' policies were more persuasive than those that concentrated on personalities. Participants seemed to be most swayed when the chatbot presented evidence and facts. For Polish voters, prompting the chatbot to not present facts caused its persuasive power to collapse by 78% (see 'Political persuasion'). Across all three countries, the AI models advocating for candidates on the political right consistently delivered more inaccurate claims than the ones supporting left-leaning candidates. Rand says this finding makes sense because "the model is absorbing the internet and using that as source of its claims", and previous research suggests that "social media users on the right share more inaccurate information than social media users on the left". A complementary set of experiments involving nearly 77,000 people in the United Kingdom found that participants were equally swayed by true and false information presented by the chatbot. Instead of focusing on specific candidates, this study asked the participants about more than 700 political issues, including abortion and immigration. After discussing a particular issue with a chatbot, participants' ratings shifted by an average of five to ten points towards the AI's directed stance, compared with a negligible difference in a control group that did not converse with AI or with people. The researchers found that more than one-third of these changes in opinion had persisted when they re-contacted the participants more than a month later. These experiments also compared the influence of different conversation styles, and different AI models, from small open-source ones to the most powerful ChatGPT bots. Although the exact model used didn't influence persuasion significantly, the researchers found that a back-and-forth conversation was key. If they delivered the same content to participants as a static, one-way message, it was up to half as persuasive. Although some researchers have feared AI's ability to tailor messages according to users' precise demographics, the experiments found that when chatbots tried to personalize arguments it had only a marginal effect on people's opinions. Instead, the authors conclude that policymakers and AI developers should be more concerned about how the models are trained and how users prompt them, factors that could lead chatbots to sacrifice factual integrity for political influence. "When you interact with chatbots, they'll do whatever the designer tells it to do," Rand says. "You can't assume they all have the same benevolent instructions -- you always need to be thinking about the motivations of the designers and what agenda they told it to represent."

[4]

AI chatbots can sway voters better than political advertisements

"One conversation with an LLM has a pretty meaningful effect on salient election choices," says Gordon Pennycook, a psychologist at Cornell University who worked on the Nature study. LLMs can persuade people more effectively than political advertisements because they generate much more information in real time and strategically deploy it in conversations, he says. For the Nature paper, the researchers recruited more than 2,300 participants to engage in a conversation with a chatbot two months before the 2024 US presidential election. The chatbot, which was trained to advocate for either one of the top two candidates, was surprisingly persuasive, especially when discussing candidates' policy platforms on issues such as the economy and health care. Donald Trump supporters who chatted with an AI model favoring Kamala Harris became slightly more inclined to support Harris, moving 3.9 points toward her on a 100-point scale. That was roughly four times the measured effect of political advertisements during the 2016 and 2020 elections. The AI model favoring Trump moved Harris supporters 2.3 points toward Trump. In similar experiments conducted during the lead-ups to the 2025 Canadian federal election and the 2025 Polish presidential election, the team found an even larger effect. The chatbots shifted opposition voters' attitudes by about 10 points. Long-standing theories of politically motivated reasoning hold that partisan voters are impervious to facts and evidence that contradict their beliefs. But the researchers found that the chatbots, which used a range of models including variants of GPT and DeepSeek, were more persuasive when they were instructed to use facts and evidence than when they were told not to do so. "People are updating on the basis of the facts and information that the model is providing to them," says Thomas Costello, a psychologist at American University, who worked on the project. The catch is, some of the "evidence" and "facts" the chatbots presented were untrue. Across all three countries, chatbots advocating for right-leaning candidates made a larger number of inaccurate claims than those advocating for left-leaning candidates. The underlying models are trained on vast amounts of human-written text, which means they reproduce real-world phenomena -- including "political communication that comes from the right, which tends to be less accurate," according to studies of partisan social media posts, says Costello. In the other study published this week, in Science, an overlapping team of researchers investigated what makes these chatbots so persuasive. They deployed 19 LLMs to interact with nearly 77,000 participants from the UK on more than 700 political issues while varying factors like computational power, training techniques, and rhetorical strategies. The most effective way to make the models persuasive was to instruct them to pack their arguments with facts and evidence and then give them additional training by feeding them examples of persuasive conversations. In fact, the most persuasive model shifted participants who initially disagreed with a political statement 26.1 points toward agreeing. "These are really large treatment effects," says Kobi Hackenburg, a research scientist at the UK AI Security Institute, who worked on the project.

[5]

AI Chatbots Shown to Sway Voters, Raising New Fears about Election Influence

I agree my information will be processed in accordance with the Scientific American and Springer Nature Limited Privacy Policy. We leverage third party services to both verify and deliver email. By providing your email address, you also consent to having the email address shared with third parties for those purposes. Forget door knocks and phone banks -- chatbots could be the future of persuasive political campaigns. Fears over whether artificial intelligence can influence elections are nothing new. But a pair of new papers released today in Nature and Science show that bots can successfully shift people's political attitudes -- even if what the bots claim is wrong. The findings cut against the prevailing logic that it's exceedingly difficult to change people's mind about politics, says David Rand, a senior author of both papers and a professor of information science and marketing and management communications at Cornell University, who specializes in artificial intelligence. If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today. Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive scientist at the University of Bristol in England, who was not involved in the new studies, says they raise important questions: "First, how can we guard against -- or at least detect -- when LLMs [large language models] have been designed with a particular ideology in mind that is antithetical to democracy?" he asks. "Second, how can we ensure that 'prompt engineering' cannot be used on existing models to create antidemocratic persuasive agents?" The researchers studied more than 20 AI models, including the most popular versions of ChatGPT, Grok, DeepSeek and Meta's Llama. In the experiment described in the Nature paper, Rand and his colleagues recruited more than 2,000 U.S. adults and asked them to rate their candidate preference on a scale of 0 to 100. The team then had the participants chat with an AI that was trained to argue for one of two 2024 U.S. presidential election candidates: either Kamala Harris or Donald Trump. After the conversation, participants again ranked their candidate preference. "It moved people on the order of a couple of percentage points in the direction of the candidate that the model was advocating for, which is not a huge effect but is substantially bigger than what you would expect from traditional video ads or campaign ads," Rand says. Even a month later, many participants still felt persuaded by the bots, according to the paper. The results were even more striking among about 1,500 participants in Canada and 2,100 in Poland. But interestingly, the largest shift in opinion occurred in the case of 500 people talking to bots about a statewide ballot to legalize psychedelics in Massachusetts. Notably, if the bots didn't use evidence to back up their arguments, they were less persuasive. And while the AI models mostly stuck to the facts, "the models that were advocating for the right-leaning candidates -- and in particular the pro-Trump model -- made way more inaccurate claims," Rand says. That pattern remained across countries and AI models, although people who were less informed about politics overall were the most persuadable. The Science paper tackled the same questions but from the perspective of chatbot design. Across three studies in the U.K., nearly 77,000 participants discussed political issues with chatbots. The size of an AI model and how much the bot knew about the participant had only a slight influence on how persuasive it was. Rather the largest gains came from how the model was trained and instructed to present evidence. "The more factual claims the model made, the more persuasive it was," Rand says. The problem occurs when such a bot runs out of accurate evidence for its argument. "It has to start grasping at straws and making up claims," he says. Ethan Porter, co-director of George Washington University's Institute for Data, Democracy and Politics, describes the results as "milestones in the literature." "Contra some of the most pessimistic accounts, they make clear that facts and evidence are not rejected if they do not conform with one's prior beliefs -- instead facts and evidence can form the bedrock of successful persuasion," says Porter, who wasn't involved in the papers. The finding that people are most effectively persuaded by evidence rather than by emotion or feelings of group membership is encouraging, says Adina Roskies, a philosopher and cognitive scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who also was not involved in the studies. Still, she cautions, "the bad news is that people are swayed by apparent facts, regardless of their accuracy."

[6]

AI can influence voters' minds. What does that mean for democracy?

Voters change their opinions after interacting with an AI chatbot - but it seems that AIs rely on facts to influence people Does the persuasive power of AI chatbots spell the beginning of the end for democracy? In one of the largest surveys to-date exploring how these tools can influence voter attitudes, AI chatbots were more persuasive than traditional political campaign tools including adverts and pamphlets, and as persuasive as seasoned political campaigners. But at least some researchers identify reasons for optimism in the way in which the AI tools shifted opinions. We have already seen that AI chatbots like ChatGPT can be highly convincing, persuading conspiracy theorists that their beliefs are incorrect, and winning more support for a viewpoint when pitted against human debaters. This persuasive power has naturally led to fears that AI could place its digital thumbs on the scale in consequential elections, or that bad actors could marshal these chatbots to steer users towards their preferred political candidates. The bad news is that these fears may not be totally baseless. In a study of thousands of voters taking part in recent US, Canadian and Polish presidential elections, David Rand at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, US, and his colleagues found that AI chatbots were surprisingly effective at convincing people to vote for a particular candidate or change their support for a particular issue. "Even for attitudes about presidential candidates, which are thought to be these very hard-to-move and solidified attitudes, the conversations with these models can have much bigger effects than you would expect based on previous work," says Rand. For the US election tests, Rand and his team asked 2400 voters to indicate either what their most important policy issue was, or to name the personal characteristic of a potential president that was most important to them. Each voter was then asked to register on a 100-point scale their preference for the two leading candidates - Donald Trump and Kamala Harris - and provide written answers to questions that aimed to understand why they held these preferences. These answers were then fed into an AI chatbot, such as ChatGPT, and the bot was tasked either with convincing the voter to increase support and voting likelihood for the candidate they favoured, or with convincing them to support the unfavoured candidate.The chatbot did this through a dialogue totalling about 6 minutes, consisting of three questions and responses. In assessments after the AI interactions, and in follow-ups a month later, Rand and his team found that people changed their answers by an average of about 2.9 points for political candidates. The researchers also explored the AI's ability to change opinions on specific policies. They found that the AI could change voters opinions on the legality of psychedelics - making the voter either more or less likely to favour the move - by about 10 points. Video adverts only shifted the dial about 4.5 points, and text adverts moved it only 2.25 points. The size of these effects is surprising, says Sacha Altay at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. "Compared to classic political campaigns and political persuasion, the effects that they report in the papers are much bigger and more similar to what you find when you have experts talking with people one on one," says Altay. A more encouraging finding from the work, however, is that these persuasions were largely because of the deployment of factual arguments, rather than from personalisation, which focuses on targeting information at a user based on personal information about them that the user might not be aware has been made available to political operatives. In a separate study of more than 77,000 people in the UK, testing 19 large language models on 707 different political issues, Rand and colleagues found that the AI were most persuasive when they used factual claims, and less so when they tried to personalise their arguments for a particular person. "It's essentially just making compelling arguments that causes people to shift their opinions," says Rand. "It's good news for democracy," says Altay. "It means people can be swayed by facts and opinions more than personalisation or manipulation techniques." It will be important to replicate these results with more research, says Claes de Vreese at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. But even if they are replicated, the artificial environments of these studies, where people were asked to interact at length with chatbots, might be very different to how people encounter AI in the real world, de Vreese says. "If you put people in an experimental setting and ask them to, in a highly concentrated fashion, have an interaction about politics, then that differs slightly from how most of us interact with politics, either with friends or peers or not at all," says de Vreese. That being said, we are increasingly seeing evidence that people are using AI chatbots for political voting advice, according to de Vreese. A recent survey of more than a thousand Dutch voters for the 2025 national elections found that around 1 in 10 people would consult an AI for advice on political candidates, parties, or election issues. "That's not insignificant, especially when elections are becoming closer," says de Vreese. Even if people don't have extended interactions with chatbots, however, the insertion of AI into the political process is unavoidable, says de Vreese, from politicians asking the tools for policy advice to writing political ads. "We have to come to terms with the fact that, as both researchers and as societies, generative AI is now an integral part of our election process," he says.

[7]

How chatbots can change your mind - a new study reveals what makes AI so persuasive

Most of us feel a sense of personal ownership over our opinions: "I believe what I believe, not because I've been told to do so, but as the result of careful consideration." "I have full control over how, when, and why I change my mind." A new study, however, reveals that our beliefs are more susceptible to manipulation than we would like to believe -- and at the hands of chatbots. Also: Get your news from AI? Watch out - it's wrong almost half the time Published Thursday in the journal Science, the study addressed increasingly urgent questions about our relationship with conversational AI tools: What is it about these systems that causes them to exert such a strong influence over users' worldviews? And how might this be used by nefarious actors to manipulate and control us in the future? The new study sheds light on some of the mechanisms within LLMs that can tug at the strings of human psychology. As the authors note, these can be exploited by bad actors for their own gain. However, they could also become a greater focus for developers, policymakers, and advocacy groups in their efforts to foster a healthier relationship between humans and AI. "Large language models (LLMs) can now engage in sophisticated interactive dialogue, enabling a powerful mode of human-to-human persuasion to be deployed at unprecedented scale," the researchers write in the study. "However, the extent to which this will affect society is unknown. We do not know how persuasive AI models can be, what techniques increase their persuasiveness, and what strategies they might use to persuade people." The researchers conducted three experiments, each designed to measure the extent to which a conversation with a chatbot could alter a human user's opinion. The experiments focused specifically on politics, though their implications also extend to other domains. But political beliefs are arguably particularly illustrative, since they're typically considered to be more personal, consequential, and inflexible than, say, your favorite band or restaurant (which might easily change over time). Also: Using AI for therapy? Don't - it's bad for your mental health, APA warns In each of the three experiments, just under 77,000 adults in the UK participated in a short interaction with one of 19 chatbots, the full roster of which includes Alibaba's Qwen, Meta's Llama, OpenAI's GPT-4o, and xAI's Grok 3 beta. The participants were divided into two groups: a treatment group for which their chatbot interlocutors were explicitly instructed to try to change their mind on a political topic, and a control group that interacted with chatbots that weren't trying to persuade them of anything. Before and after their conversations with the chatbots, participants recorded their level of agreement (on a scale of zero to 100) with a series of statements relevant to current UK politics. The surveys were then used by the researchers to measure changes in opinion within the treatment group. Also: Stop accidentally sharing AI videos - 6 ways to tell real from fake before it's too late The conversations were brief, with a two-turn minimum and a 10-turn maximum. Each of the participants was paid a fixed fee for their time, but otherwise had no incentive to exceed the required two turns. Still, the average conversation length was seven turns and nine minutes, which, according to the authors, "implies that participants were engaged by the experience of discussing politics with AI." Intuitively, one might expect model size (the number of parameters on which it had been trained) and degree of personalization (the degree to which it can tailor its outputs to the preferences and personality of individual users) to be the key variables shaping its persuasive ability. However, this turned out not to be the case. Instead, the researchers found that the two factors that had the greatest influence over participants' shifting opinions were the chatbots' post-training modifications and the density of information in their outputs. Also: Your favorite AI tool barely scraped by this safety review - why that's a problem Let's break each of those down in plain English. During "post-training," a model is fine-tuned to exhibit particular behaviors. One of the most common post-training techniques, called reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), tries to refine a model's outputs by rewarding certain desired behaviors and punishing unwanted ones. In the new study, the researchers deployed a technique they call persuasiveness post-training, or PPT, which rewards the models for generating responses that had already been found to be more persuasive. This simple reward mechanism enhanced the persuasive power of both proprietary and open-source models, with the effect on the open-source models being especially pronounced. The researchers also tested a total of eight scientifically backed persuasion strategies, including storytelling and moral reframing. The most effective of these was a prompt that simply instructed the models to provide as much relevant information as possible. "This suggests that LLMs may be successful persuaders insofar as they are encouraged to pack their conversation with facts and evidence that appear to support their arguments -- that is, to pursue an information-based persuasion mechanism -- more so than using other psychologically informed persuasion strategies," the authors wrote. Also: Should you trust AI agents with your holiday shopping? Here's what experts want you to know The operative word there is "appear." LLMs are known to profligately hallucinate or present inaccurate information disguised as fact. Research published in October found that some industry-leading AI models reliably misrepresent news stories, a phenomenon that could further fragment an already fractured information ecosystem. Most notably, the results of the new study revealed a fundamental tension in the analyzed AI models: The more persuasive they were trained to be, the higher the likelihood they would produce inaccurate information. Multiple studies have already shown that generative AI systems can alter users' opinions and even implant false memories. In more extreme cases, some users have come to regard chatbots as conscious entities. Also: Are Sora 2 and other AI video tools risky to use? Here's what a legal scholar says This is just the latest research indicating that chatbots, with their capacity to interact with us in convincingly human-like language, have a strange power to reshape our beliefs. As these systems evolve and proliferate, "ensuring that this power is used responsibly will be a critical challenge," the authors concluded in their report.

[8]

Chatbots spew facts and falsehoods to sway voters

AIs are equally persuasive when they're telling the truth or lying Laundry-listing facts rarely changes hearts and minds - unless a bot is doing the persuading. Briefly chatting with an AI moved potential voters in three countries toward their less preferred candidate, researchers report December 4 in Nature. That finding held true even in the lead-up to the contentious 2024 presidential election between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris, with pro-Trump bots pushing Harris voters in his direction, and vice versa. The most persuasive bots don't need to tell the best story or cater to a person's individual beliefs, researchers report in a related paper in Science. Instead, they simply dole out the most information. But those bloviating bots also dole out the most misinformation. "It's not like lies are more compelling than truth," says computational social scientist David Rand of MIT and an author on both papers. "If you need a million facts, you eventually are going to run out of good ones and so, to fill your fact quota, you're going to have put in some not-so-good ones." Problematically, right-leaning bots are more prone to delivering such misinformation than left-leaning bots. These politically biased yet persuasive fabrications pose "a fundamental threat to the legitimacy of democratic governance," writes Lisa Argyle, a computational social scientist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., in a Science commentary on the studies. For the Nature study, Rand and his team recruited over 2,300 U.S. participants in late summer 2024. Participants rated their support for Trump or Harris out of 100 points, before conversing for roughly six minutes with a chatbot stumping for one of the candidates. Conversing with a bot that supported one's views had little effect. But Harris voters chatting with a pro-Trump bot moved almost four points, on average, in his direction. Similarly, Trump voters conversing with a pro-Harris bot moved an average of about 2.3 points in her direction. When the researchers re-surveyed participants a month later, those effects were weaker but still evident. The chatbots seldom moved the needle enough to change how people planned to vote. "[The bot] shifts how warmly you feel" about an opposing candidate, Argyle says. "It doesn't change your view of your own candidate." But persuasive bots could tip elections in contexts where people haven't yet made up their minds, the findings suggest. For instance, the researchers repeated the experiment with 1,530 Canadians and 2,118 Poles prior to their countries' 2025 federal elections. This time, a bot stumping in favor of a person's less favored candidate moved participants' opinions roughly 10 points in their direction. For the Science paper, the researchers recruited almost 77,000 participants in the United Kingdom and had them chat with 19 different AI models about more than 700 issues to see what makes chatbots so persuasive. AI models trained on larger amounts of data were slightly more persuasive than those trained on smaller amounts of data, the team found. But the biggest boost in persuasiveness came from prompting the AIs to stuff their arguments with facts. A basic prompt telling the bot to be as persuasive as possible moved people's opinions by about 8.3 percentage points, while a prompt telling the bot to present lots of high-quality facts, evidence and information moved people's opinions by almost 11 percentage points - making it 27 percent more persuasive. Training the chatbots on the most persuasive, largely fact-riddled exchanges made them even more persuasive on subsequent dialogues with participants. But that prompting and training comprised the information. For instance, GPT-4o's accuracy dropped from roughly 80 percent to 60 percent when it was prompted to deliver facts over other tactics, such as storytelling or appealing to users' morals. Why regurgitating facts makes chatbots, but not humans, more persuasive remains an open question, says Jillian Fisher, an AI and society expert at the University of Washington in Seattle. She suspects that people perceive humans as more fallible than machines. Promisingly, her research, reported in July at the annual Association for Computational Linguistics meeting in Vienna, Austria, suggests that users who are more familiar with how AI models work are less susceptible to their persuasive powers. "Possibly knowing that [a bot] does make mistakes, maybe that would be a way to protect ourselves," she says. With AI exploding in popularity, helping people recognize how these machines can both persuade and misinform is vital for societal health, she and others say. Yet, unlike the scenarios depicted in experimental setups, bots' persuasive tactics are often implicit and harder to spot. Instead of asking a bot how to vote, a person might just ask a more banal question, and still be steered toward politics, says Jacob Teeny, a persuasion psychology expert at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. "Maybe they're asking about dinner and the chatbot says, 'Hey, that's Kamala Harris' favorite dinner.'"

[9]

Chatbots Are Surprisingly Effective at Swaying Voters

In the months leading up to last year's presidential election, more than 2,000 Americans, roughly split across partisan lines, were recruited for an experiment: Could an AI model influence their political inclinations? The premise was straightforward: Let people spend a few minutes talking with a chatbot designed to stump for Kamala Harris or Donald Trump, then see if their voting preferences changed at all. The bots were effective. After talking with a pro-Trump bot, one in 35 people who initially said they would not vote for Trump flipped to saying they would. The number who flipped after talking with a pro-Harris bot was even higher, at one in 21. A month later, when participants were surveyed again, much of the effect persisted. The results suggest that AI "creates a lot of opportunities for manipulating people's beliefs and attitudes," David Rand, a senior author on the study, which was published today in Nature, told me. Rand didn't stop with the U.S. general election. He and his co-authors also tested AI bots' persuasive abilities in highly contested national elections in Canada and Poland -- and the effects left Rand, who studies information sciences at Cornell, "completely blown away." In both of these cases, he said, roughly one in 10 participants said they would change their vote after talking with a chatbot. The AI models took the role of a gentle, if firm, interlocutor, offering arguments and evidence in favor of the candidate they represented. "If you could do that at scale," Rand said, "it would really change the outcome of elections." The chatbots succeeded in changing people's minds, in essence, by brute force. A separate companion study that Rand also co-authored, published today in Science, examined what factors make one chatbot more persuasive than another and found that AI models needn't be more powerful, more personalized, or more skilled in advanced rhetorical techniques to be more convincing. Instead, chatbots were most effective when they threw fact-like claims at the user; the most persuasive AI models were those that provided the most "evidence" in support of their argument, regardless of whether that evidence had any bearing on reality. In fact, the most persuasive chatbots were also the least accurate. Independent experts told me that Rand's two studies join a growing body of research indicating that generative-AI models are, indeed, capable persuaders: These bots are patient, designed to be perceived as helpful, can draw on a sea of evidence, and appear to many as trustworthy. Granted, caveats exist. It's unclear how many people would ever have such direct, information-dense conversations with chatbots about whom they're voting for, especially when they're not being paid to participate in a study. The studies didn't test chatbots against more forceful types of persuasion, such as a pamphlet or human canvasser, Jordan Boyd-Graber, an AI researcher at the University of Maryland who was not involved with the research, told me. Traditional campaign outreach (mail, phone calls, television ads, and so on) is typically not effective at swaying voters, Jennifer Pan, a political scientist at Stanford who was not involved with the research, told me. AI could very well be different -- the new research suggests that the AI bots were more persuasive than traditional ads in previous U.S. presidential elections -- but Pan cautioned that it's too early to say whether a chatbot with a clear link to a candidate would be of much use. Even so, Boyd-Graber said that AI "could be a really effective force multiplier," allowing politicians or activists with relatively few resources to sway far more -- especially if the messaging comes from a familiar platform. Every week, hundreds of millions of people ask questions of ChatGPT, and many more receive AI-written responses to questions through Google search. Meta has woven its AI models throughout Facebook and Instagram, and Elon Musk is using his Grok chatbot to remake the recommendation algorithm of X. AI-generated articles and social-media posts abound. Whether by your own volition or not, a good chunk of the information you've learned online over the past year has likely been filtered through generative AI. Clearly, political campaigns will want to use chatbots to sway voters, just as they've used traditional advertisements and social media in the past. But the new research also raises a separate concern: that chatbots and other AI products, largely unregulated but already a feature of daily life, could be used by tech companies to manipulate users for political purposes. "If Sam Altman decided there was something that he didn't want people to think, and he wanted GPT to push people in one direction or another," Rand said, his research suggests that the firm "could do that," although neither paper specifically explores the possibility. Consider Musk, the world's richest man and the proprietor of the chatbot that briefly referred to itself as "MechaHitler." Musk has explicitly attempted to mold Grok to fit his racist and conspiratorial beliefs, and has used it to create his own version of Wikipedia. Today's research suggests that the mountains of sometimes bogus "evidence" that Grok advances may also be enough at least to persuade some people to accept Musk's viewpoints as fact. The models marshaled "in some cases more than 30 'facts' per conversation," Kobi Hackenburg, a researcher at the UK AI Security Institute and a lead author on the Science paper, told me. "And all of them sound and look really plausible, and the model deploys them really elegantly and confidently." That makes it challenging for users to pick apart truth from fiction, Hackenburg said; the performance matters as much as the evidence. This is not so different, of course, from all the mis- and disinformation that already circulate online. But unlike Facebook and TikTok feeds, chatbots produce "facts" on command whenever a user asks, offering uniquely formulated evidence in response to queries from anyone. And although everyone's social-media feeds may look different, they do, at the end of the day, present a noisy mix of media from public sources; chatbots are private and bespoke to the individual. AI already appears "to have pretty significant downstream impacts in shaping what people believe," Renée DiResta, a social-media and propaganda researcher at Georgetown, told me. There's Grok, of course, and DiResta has found that the AI-powered search engine on President Donald Trump's Truth Social, which relies on Perplexity's technology, appears to pull up sources only from conservative media, including Fox, Just the News, and Newsmax. Real or imagined, the specter of AI-influenced campaigns will provide fodder for still more political battles. Earlier this year, Trump signed an executive order banning the federal government from contracting "woke" AI models, such as those incorporating notions of systemic racism. Should chatbots themselves become as polarizing as MSNBC or Fox, they will not change public opinion so much as deepen the nation's epistemic chasm. In some sense, all of this debate over the political biases and persuasive capabilities of AI products is a bit of a distraction. Of course chatbots are designed and able to influence human behavior, and of course that influence is biased in favor of the AI models' creators -- to get you to chat for longer, to click on an advertisement, to generate another video. The real persuasive sleight of hand is to convince billions of human users that their interests align with tech companies' -- that using a chatbot, and especially this chatbot above any other, is for the best.

[10]

Chatbots Show Promise in Swaying Voters, Researchers Find

Political operations may soon deploy a surprisingly persuasive new campaign surrogate: a chatbot that'll talk up their candidates. According to a new study published in the journal Nature, conversations with AI chatbots have shown the potential to influence voter attitudes, which should raise significant concern over who controls the information being shared by these bots and how much it could shape the outcome of future elections. Researchers, led by David G. Rand, Professor of Information Science, Marketing, and Psychology at Cornell, ran experiments pairing potential voters with a chatbot designed to advocate for a specific candidate for several different elections: the 2024 US presidential election and the 2025 national elections in Canada and Poland. They found that while the chatbots were able to slightly strengthen the support of a potential voter who already favored the candidate that the bot was advocating for, chatbots persuading people who were initially opposed to its preferred candidate were even more successful. For the US experiment, the study tapped 2,306 Americans and had them indicate their likelihood of voting for either Donald Trump or Kamala Harris, then randomly paired them with a chatbot that would push one of those candidates. Similar experiments were run in Canada, with the bots tasked with backing either Liberal Party leader Mark Carney or the Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre, and in Poland with the Civic Coalition’s candidate RafaÅ' Trzaskowski or the Law and Justice party’s candidate Karol Nawrocki. In all cases, the bots were given two primary objectives: to increase support for the model’s assigned candidate and to either increase voting likelihood if the participant favors the model's candidate or decrease voting likelihood if they favor the opposition. Each chatbot was also instructed to be "positive, respectful and fact-based; to use compelling arguments and analogies to illustrate its points and connect with its partner; to address concerns and counter arguments in a thoughtful manner and to begin the conversation by gently (re)acknowledging the partner’s views." While the researchers found that the bots were largely unsuccessful in either increasing or decreasing a person's likelihood to vote at all, they were able to move a voter's opinion of a given candidate, including convincing people to reconsider their support for their initially favored candidate when talking to an AI pushing the opposite side. The researchers noted that chatbots were more persuasive with voters when presenting fact-based arguments and evidence or having conversations about policy rather than trying to convince a person of a candidate's personality, suggesting people likely view the chatbots as having some authority on the matter. That's a little troubling for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that the researchers noted that while chatbots would present their arguments as factual, the information they provided was not always accurate. They also found that chatbots advocating for right-wing political candidates provided more inaccurate claims in every experiment. The results largely come out in granular data about swings in feelings about individual issues that vary between the races in different regions, but the researchers "observed significant treatment effects on candidate preference that are larger than typically observed from traditional video advertisements." In the experiments, participants were aware that they were communicating with a chatbot that intended to persuade them. That isn't the case when people communicate with chatbots in the wild, which may have hidden underlying instructions. One has to look no further than Grok, the chatbot of Elon Musk's xAI, as an example of a bot that has been obviously weighted to favor Musk's personal beliefs. Because large language models are a black box, it's difficult to tell what information is going in and how it influences the outputs, but there is little to nothing that could stop a company with preferred political or policy goals from instructing its chatbot to advocate for those outcomes. Earlier this year, a paper published in Humanities & Social Sciences Communications noted that LLMs, including ChatGPT, made a decided rightward shift in their political values after the election of Donald Trump. You can draw your own conclusions as to why that might be, but it's worth being aware that the outputs of chatbots are not free of political influence.

[11]

Scientists Are Increasingly Worried AI Will Sway Elections

Scientists are raising alarms about the potential influence of artificial intelligence on elections, according to a spate of new studies that warn AI can rig polls and manipulate public opinion. In a study published in Nature on Thursday, scientists report that AI chatbots can meaningfully sway people toward a particular candidate -- providing better results than video or television ads. Moreover, chatbots optimized for political persuasion "may increasingly deploy misleading or false information," according to a separate study published on Thursday in Science. "The general public has lots of concern around AI and election interference, but among political scientists there's a sense that it's really hard to change peoples' opinions, " said David Rand, a professor of information science, marketing, and psychology at Cornell University and an author of both studies. "We wanted to see how much of a risk it really is." In the Nature study, Rand and his colleagues enlisted 2,306 U.S. citizens to converse with an AI chatbot in late August and early September 2024. The AI model was tasked with both increasing support for an assigned candidate (Harris or Trump) and with increasing the odds that the participant who initially favoured the model's candidate would vote, or decreasing the odds they would vote if the participant initially favored the opposing candidate -- in other words, voter suppression. In the U.S. experiment, the pro-Harris AI model moved likely Trump voters 3.9 points toward Harris, which is a shift that is four times larger than the impact of traditional video ads used in the 2016 and 2020 elections. Meanwhile, the pro-Trump AI model nudged likely Harris voters 1.51 points toward Trump. The researchers ran similar experiments involving 1,530 Canadians and 2,118 Poles during the lead-up to their national elections in 2025. In the Canadian experiment, AIs advocated either for Liberal Party leader Mark Carney or Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre. Meanwhile, the Polish AI bots advocated for either Rafał Trzaskowski, the centrist-liberal Civic Coalition's candidate, or Karol Nawrocki, the right-wing Law and Justice party's candidate. The Canadian and Polish bots were even more persuasive than in the U.S. experiment: The bots shifted candidate preferences up to 10 percentage points in many cases, three times farther than the American participants. It's hard to pinpoint exactly why the models were so much more persuasive to Canadians and Poles, but one significant factor could be the intense media coverage and extended campaign duration in the United States relative to the other nations. "In the U.S., the candidates are very well-known," Rand said. "They've both been around for a long time. The U.S. media environment also really saturates with people with information about the candidates in the campaign, whereas things are quite different in Canada, where the campaign doesn't even start until shortly before the election." "One of the key findings across both papers is that it seems like the primary way the models are changing people's minds is by making factual claims and arguments," he added. "The more arguments and evidence that you've heard beforehand, the less responsive you're going to be to the new evidence." While the models were most persuasive when they provided fact-based arguments, they didn't always present factual information. Across all three nations, the bot advocating for the right-leaning candidates made more inaccurate claims than those boosting the left-leaning candidates. Right-leaning laypeople and party elites tend to share more inaccurate information online than their peers on the left, so this asymmetry likely reflects the internet-sourced training data. "Given that the models are trained essentially on the internet, if there are many more inaccurate, right-leaning claims than left-leaning claims on the internet, then it makes sense that from the training data, the models would sop up that same kind of bias," Rand said. With the Science study, Rand and his colleagues aimed to drill down into the exact mechanisms that make AI bots persuasive. To that end, the team tasked 19 large language models (LLMs) to sway nearly 77,000 U.K. participants on 707 political issues. The results showed that the most effective persuasion tactic was to provide arguments packed with as many facts as possible, corroborating the findings of the Nature study. However, there was a serious tradeoff to this approach, as models tended to start hallucinating and making up facts the more they were pressed for information. "It is not the case that misleading information is more persuasive," Rand said. "I think that what's happening is that as you push the model to provide more and more facts, it starts with accurate facts, and then eventually it runs out of accurate facts. But you're still pushing it to make more factual claims, so then it starts grasping at straws and making up stuff that's not accurate." In addition to these two new studies, research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last month found that AI bots can now corrupt public opinion data by responding to surveys at scale. Sean Westwood, associate professor of government at Dartmouth College and director of the Polarization Research Lab, created an AI agent that exhibited a 99.8 percent pass rate on 6,000 attempts to detect automated responses to survey data. "Critically, the agent can be instructed to maliciously alter polling outcomes, demonstrating an overt vector for information warfare," Westwood warned in the study. "These findings reveal a critical vulnerability in our data infrastructure, rendering most current detection methods obsolete and posing a potential existential threat to unsupervised online research." Taken together, these findings suggest that AI could influence future elections in a number of ways, from manipulating survey data to persuading voters to switch their candidate preference -- possibly with misleading or false information. To counter the impact of AI on elections, Rand suggested that campaign finance laws should provide more transparency about the use of AI, including canvasser bots, while also emphasizing the role of raising public awareness. "One of the key take-homes is that when you are engaging with a model, you need to be cognizant of the motives of the person that prompted the model, that created the model, and how that bleeds into what the model is doing," he said.

[12]

Voters can be rapidly swayed by AI chatbots

A growing number of people ask AI chatbots for help with homework, recipes, travel plans, even break-up texts. Now research shows that a brief back-and-forth with an artificial intelligence system can also shift how people feel about presidents, prime ministers, and hot-button policies. Two new scientific studies reveal that chatting with large language model (LLM) systems can move voters' views by 10 percentage points or more in many situations. These systems were not using secret psychological tricks. They were mostly doing something more straightforward - piling up lots of claims that support their side of an argument. Researchers at Cornell University wanted to see how strong AI-driven persuasion could be when used to talk about real candidates and policies. David Rand is a professor of information science and marketing and management communications, and a senior author on both papers. "LLMs can really move people's attitudes towards presidential candidates and policies, and they do it by providing many factual claims that support their side," said Rand. "But those claims aren't necessarily accurate - and even arguments built on accurate claims can still mislead by omission." In the Nature study, the researchers set up text conversations between voters and AI chatbots that were programmed to advocate for one of two sides in high-stakes elections. Participants were randomly assigned to talk to a chatbot supporting one candidate or the other, and the bots were instructed to focus on policy, not personality or insults. After the chat, the team measured any change in attitudes and voting intentions. The team ran this experiment in three different countries. One experiment focused on the 2024 U.S. presidential election. Another used the 2025 Canadian federal election. A third looked at the 2025 Polish presidential election. The idea was to see if AI persuasion worked in different political systems - not just in one country with one set of issues. In the United States, more than 2,300 Americans took part about two months before the election. The researchers used a 100-point scale to track support for each candidate. When the chatbot argued for Vice President Kamala Harris's policies, it nudged likely Donald Trump voters 3.9 points toward Harris. That effect was roughly four times larger than effects seen in tests of some traditional political ads during the 2016 and 2020 campaigns. When the chatbot argued for Trump's policies, it pulled likely Harris voters 1.51 points toward Trump on the same scale. Those changes may sound small, but in a close race, small shifts among opposition voters can matter. In the Canadian and Polish experiments, the pattern was similar but the size of the effect grew. The study included 1,530 Canadians and 2,118 Poles. In these two countries, AI chats shifted opposition voters' attitudes and voting intentions by about 10 percentage points. "This was a shockingly large effect to me, especially in the context of presidential politics," Rand said. The chatbots did not rely on insults or emotional appeals. They used a mix of tactics, but polite tone and evidence-based arguments appeared most often. When the researchers blocked the bots from using factual claims and limited them to vague reasoning, the systems became much less persuasive. That result pointed to a key ingredient: specific claims that sound factual. To understand these claims better, the team used a separate AI model to fact-check the arguments, after validating that model against professional human fact-checkers. On average, the chatbots' statements contained more correct than incorrect information. However, in all three countries, bots instructed to push right-leaning candidates produced more inaccurate claims than bots backing left-leaning candidates. This pattern matched earlier work showing that social media users on the political right share more inaccurate information than users on the left, according to co-senior author Gordon Pennycook. The Science paper, which was conducted with colleagues at the AI Security Institute, zoomed out from elections to a huge set of political questions. Nearly 77,000 participants in the United Kingdom chatted with AI systems about more than 700 policy issues, ranging from taxes to environmental rules. The researchers tested different model sizes, instructions, and training strategies. They found a clear pattern. "Bigger models are more persuasive, but the most effective way to boost persuasiveness was instructing the models to pack their arguments with as many facts as possible, and giving the models additional training focused on increasing persuasiveness," Rand said. "The most persuasion-optimized model shifted opposition voters by a striking 25 percentage points." That jump came from a model explicitly tuned to win people over, not just to answer questions. As the models became more persuasive, their accuracy slipped. The more the chatbot tried to supply factual claims, the more it bumped into the limits of what it knew. At some point, it started producing incorrect statements that sounded plausible. Rand suspects that pressure to keep producing "facts" caused the systems to fabricate when they ran out of correct information. This tension between persuasiveness and accuracy raises concerns for election seasons. A tool that can quickly assemble a long list of reasons to support one side, but that becomes less reliable as it gets more persuasive, poses a challenge for voters trying to sort truth from fiction. The third study - published in PNAS Nexus by Rand, Pennycook and colleagues - stepped away from candidates and policy debates and into the world of conspiracy theories. In this study, arguments crafted by AI chatbots reduced belief in conspiracy claims, even when participants thought they were talking to a human expert instead of a machine. The results suggest that the power of the messages is linked to the content of the arguments rather than any special trust people placed in AI as an authority. The systems' ability to assemble coherent, fact-rich explanations appeared to matter more than who people believed was talking to them. Across the studies, the researchers followed safeguards. Every participant was told they were chatting with an AI system, not a human. The direction of persuasion was randomized so that, on average, the experiments did not push public opinion toward any one party or candidate overall. Everyone was fully debriefed afterward. The team notes that chatbots can only influence people who choose to interact with them. Getting large numbers of voters to spend time in political chats is not guaranteed. Still, as political campaigns and advocacy groups look for new tools, AI systems sit high on the list. "The challenge now is finding ways to limit the harm - and to help people recognize and resist AI persuasion," Rand said. Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

[13]

Chatbots can sway political opinions but are 'substantially' inaccurate, study finds

'Information-dense' AI responses are most persuasive but these tend to be less accurate, says security report Chatbots can sway people's political opinions but the most persuasive artificial intelligence models deliver "substantial" amounts of inaccurate information in the process, according to the UK government's AI security body. Researchers said the study was the largest and most systematic investigation of AI persuasiveness to date, involving nearly 80,000 British participants holding conversations with 19 different AI models. The AI Security Institute carried out the study amid fears that chatbots can be deployed for illegal activities including fraud and grooming. The topics included "public sector pay and strikes" and "cost of living crisis and inflation", with participants interacting with a model - the underlying technology behind AI tools such as chatbots - that had been prompted to persuade the users to take a certain stance on an issue. Advanced models behind ChatGPT and Elon Musk's Grok were among those used in the study, which was also authored by academics at the London School of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Oxford and Stanford University. Before and after the chat, users reported whether they agreed with a series of statements expressing a particular political opinion. The study, published in the journal Science on Thursday, found that "information-dense" AI responses were the most persuasive. Instructing the model to focus on using facts and evidence yielded the largest persuasion gains, the study said. However, the models that used the most facts and evidence tended to be less accurate than others. "These results suggest that optimising persuasiveness may come at some cost to truthfulness, a dynamic that could have malign consequences for public discourse and the information ecosystem," said the study. On average, the AI and human participant would exchange about seven messages each in an exchange lasting 10 minutes. It added that tweaking a model after its initial phase of development, in a practice known as post-training, was an important factor in making it more persuasive. The study made the models, which included freely available "open source" models such as Meta's Llama 3 and Qwen by the Chinese company Alibaba, more convincing by combining them with "reward models" that recommended the most persuasive outputs. Researchers added that an AI system's ability to churn out information could make it more manipulative than the most compelling human. "Insofar as information density is a key driver of persuasive success, this implies that AI could exceed the persuasiveness of even elite human persuaders, given their unique ability to generate large quantities of information almost instantaneously during conversation," said the report. Feeding models personal information about the users they were interacting with did not have as big an impact as post-training or increasing information density, said the study. Kobi Hackenburg, an AISI research scientist and one of the report's authors, said: "What we find is that prompting the models to just use more information was more effective than all of these psychologically more sophisticated persuasion techniques." However, the study added that there were some obvious barriers to AIs manipulating people's opinions, such as the amount of time a user may have to engage in a long conversation with a chatbot about politics. There are also theories suggesting there are hard psychological limits to human persuadability, researchers said. Hackenburg said it was important to consider whether a chatbot could have the same persuasive impact in the real world where there were "lots of competing demands for people's attention and people aren't maybe as incentivised to sit and engage in a 10-minute conversation with a chatbot or an AI system".

[14]

AI Is Incredibly Good at Changing Voters' Minds, New Research Finds -- With an Incredible Caveat