AI Breakthrough Detects Ancient Life Signatures in 3.3-Billion-Year-Old Rocks

6 Sources

6 Sources

[1]

AI spots 'ghost' signatures of ancient life on Earth

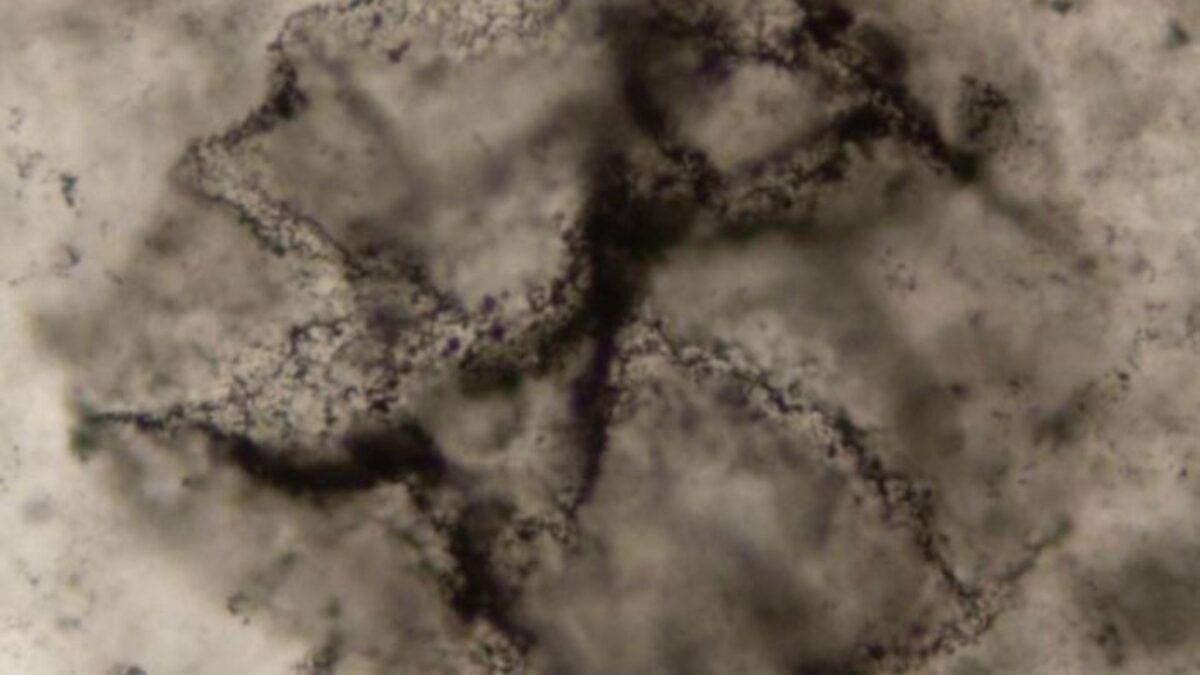

In searching for the earliest life on Earth and other worlds, researchers normally look for intact fossils or biomolecules made only by living organisms. But such signals are few and far between. Now, researchers have devised an artificial intelligence (AI) that can identify signs of ancient life in rocks of unknown provenance, based only on the pattern of chemicals left behind as biomolecules degrade over eons. "We have a way to read molecular 'ghosts' left behind by early life," says Robert Hazen, a geologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science who led the study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Using this automated pattern recognition technique, the researchers say they can see life's signature in 3.3-billion-year-old rocks, which is hundreds of millions of years shy of the indication of life in Earth's oldest fossils. But the new work also claims to push back the biomolecular signature of the earliest photosynthetic life some 800 million years to 2.5 billion years ago. Researchers are now working to adapt this approach to search for signs of life on Mars and moons of Jupiter and Saturn. "This could pan out to be very, very important," says Karen Lloyd, a microbial biogeochemist at the University of Southern California who was not involved in the study. "It's a great way to look for biosignatures." Still-debated microfossil evidence for the earliest life on Earth dates back more 3.7 billion years ago, in the form of rocks containing filaments made by microbes living around hydrothermal vents in what's now Canada. In addition, mats of bacteria in what's now Western Australia laid down more conclusive fossil evidence in mounded structures called stromatolites some 3.5 billion years ago. But such fossils from Earth's youth are extremely rare. Researchers have tried to fill out that record by searching for ancient sediments that contain not fossils, but chemical and molecular signs of life. Only living organisms are thought to be capable of making certain lipids and ring-shaped compounds called porphyrins, for example. But Earth's tectonic machinery tends to obliterate such signs, by burying, crushing, heating, and cooling the sediments. Indirect measures also offer clues. For instance, rocks more than 3.7 billion years old are enriched with carbon-12, a light isotope that's preferred by living organisms, compared with the heavier isotope carbon-13. Still, finding conclusive molecular biosignatures "has not proven an easy problem at all," says Woodward Fischer, a geobiologist at the California Institute of Technology. So, Hazen and his colleagues decided to drop the search for intact, biomolecular smoking guns. Instead, they wondered whether they could spot telltale patterns in the molecular detritus these compounds leave behind as they break down. To do so, the team amassed more than 400 samples. Some were rock and sediment samples known to contain either living or fossil organisms. Others were abiotic samples from meteorites. The team analyzed them with a tool called a pyrolysis gas chromatograph mass spectrometer (GC-MS). The device heated the samples to more than 600°C, breaking them apart into volatile fragments. The fragments were then separated by their physical and chemical properties, identified, and tallied by their concentration. Carnegie astrobiologist Michael Wong, the study's first author, likens the instrument to "a really fancy oven that not only bakes your cake, but tastes it for you, too." In the end, each sample was transformed into a landscape of data, with up to hundreds of thousands of individual peaks that each represented a different possible molecular fragment. They then used a conventional machine learning technique, known as a random forest model, to look for patterns in both what was present and what was missing. "What the machine learning model does is essentially try to use every single one of those data landscapes as a fingerprint to find what is similar to each other and what is different," says Carnegie geoinformatics expert Anirudh Prabhu. After using 75% of the samples to train their AI, the researchers then let it loose on the rest. For test samples, the AI correctly distinguished between biological and abiotic samples with more than 90% accuracy. It also saw chemical patterns unique to biology in rocks as old as 3.3 billion years, nearly twice as old as previous biomolecular signatures preserved in ancient rocks. In addition, the AI teased out the molecular pattern associated with oxygen-producing photosynthesis in rocks up to 2.5 billion years old. Although there is plentiful geochemical evidence for photosynthetic life around that time from the sudden explosion of oxygen it produced, preserved evidence of these organisms' molecular machinery is scant. The new results push back the molecular signature of photosynthetic life by more than 800 million years, the authors say. Not all signatures were easy to see. For samples believed to be biotic, in rocks 500 million to 2.5 billion years old, the AI identified signatures of life about two-thirds of the time. But in rocks older than 2.5 billion years, that number dropped to 47%. For each sample, the model didn't just report whether life's signature was present, it also provided a probability score. If a sample scored above 60% for "biotic," it was considered a strong hit. "The confidence is not as good as you'd want it to be," Lloyd says. Still, she notes, that could change as researchers bolster the AI's training data with more samples. The researchers are eager to test the system on extraterrestrial samples. According to Prabhu, the model "opens the door to exploring ancient and alien environments with a fresh lens, guided by patterns we might not even know to look for ourselves." Wong adds that this biosignature pattern recognition should also work with other analytical tools, which could help future robotic missions to Mars, Jupiter's moon Europa, and Saturn's moon Enceladus broaden their search for signatures of extraterrestrial life. Wong's group is starting a new, $5 million, NASA-funded project to do just that. The goal, he says, is to "answer one of the greatest scientific questions we still have left to answer, which is: Are we alone in the universe?"

[2]

AI Uncovers Oldest-Ever Molecular Evidence of Photosynthesis

A machine-learning breakthrough could lift the veil on Earth's early history -- and supercharge the search for alien life While much of the history of life on Earth is written, the opening chapters are murky at best. On our ever-changing world, the older a rock is, the more it has changed, obscuring or even erasing evidence of ancient life. Beyond a hazy boundary of circa two billion years, in fact, this interference is so total that no pristine, unaltered Earth rocks are known to exist, making any potential sign of biology as clear as mud. At least until now. In a study published on November 17 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a group of researchers say they've leveraged artificial intelligence to follow life's trail further back in time than ever before, using machine learning to distinguish the echoes of biology from mere abiotic organic molecules in rocks as old as 3.3 billion years. The results could more than double how far back in time scientists can convincingly claim to discern molecular signs of life in ancient rocks, the study authors say, citing previous record-setting measurements involving 1.6-billion-year-old rocks. If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today. The study also flags signs of photosynthesis in 2.5-billion-year-old rocks -- some 800 million years earlier than any other confirmed biomolecular evidence. The authors suggest that in the not-too-distant future similar techniques may be used to seek signs of alien life on Mars or the icy ocean moons of the outer solar system. And such astrobiological applications wouldn't necessarily demand the extremely costly task of retrieving material from Mars or any other extraterrestrial locale for in-depth study in labs back on Earth. "Our approach could run on board a rover -- no need to send samples home," says the study's first author, Michael Wong, an astrobiologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science. According to Karen Lloyd, a biogeochemist at the University of Southern California uninvolved with the study, the technique holds promise as an "agnostic" way of looking for life, independent of Earth-bound assumptions. "This allows for the possible extrapolation from an extremely varied and diverse dataset of biomolecules in known living matter, extending to matter that may or may not have come from living things," Lloyd says. "This is really helpful in the search for life on rocks that come from ancient Earth -- as well as rocks that come from extraterrestrial bodies." Rocks containing familiar fossils -- dinosaurs, ferns, fish, trilobites and so on -- may seem creakingly ancient, but in fact represent less than the latest 10 percent of Earth's 4.5-billion-year history. Put another way, for each of the circa 500 million years that make up the ongoing Phanerozoic (Greek for "visible life") Eon, there exists nearly a decade of underlying planetary time in which early life flourished almost imperceptibly, scarcely registering in the fossil record beyond trace molecules such as lipids and amino acids. The trouble, says lead author and Carnegie geologist Robert Hazen, is that those molecules degrade and disappear over time. "Our method looks for patterns instead, like facial recognition for molecular fragments," he explains. "Think of the burnt Herculaneum scrolls that AI helped 'read.' You and I just see dots and squiggles, but AI can reconstruct letters and words." The team began by gathering more than 400 samples -- some modern, some ancient, some from known abiotic sources like meteorites, others filled with fossils or living microbes, and several containing organic molecules but no obvious indicators of life. They fed them into an instrument called a pyrolysis gas chromatograph mass spectrometer (Py-GC-MS), which vaporized each sample to release and then categorize their constituent molecular fragments by mass and other properties. This yielded a rich "chemical landscape" for each sample, filled with tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of peaks denoting different possible compounds and ripe for the AI's pattern-spotting scrutiny. After training the AI on about 75 percent of the sample data, the researchers unleashed it on the remaining 25 percent. The system correctly distinguished between biotic and abiotic samples for more than 90 percent of that material, but its certainty dwindled as a rock's age and level of degradation increased; for samples older than 2.5 billion years, the AI flagged less than half as having a biotic origin, and with lower overall confidence. Even so, it was very old samples from South Africa that led to the team's most spectacular conclusions -- signs of biogenic molecules in 3.3-billion-year-old specimens from a formation called the Josefsdal Chert, and evidence of ancient oxygen-producing photosynthesis in 2.5-billion-year-old rocks from the Gamohaan Formation. Preexisting geochemical evidence meant neither result was a surprise, but being backed up by biomolecular data is a true breakthrough. "The key is that our validation set included truly unknown samples -- some debated for decades," says paper co-author Anirudh Prabhu, who studies geoinformatics at Carnegie. "And the model made independent predictions that sometimes confirmed existing suspicions." The most surprising finds came from the AI outsmarting its human tenders. The system flagged a dead seashell as photosynthetic -- an error, it seemed, until the researchers realized the system had picked up algae growing on the shell. A similar photosynthesis "false alarm" arose for a wasp's nest, which the AI correctly linked to the chewed-up wood from which the nest was made. "The model was right -- just for the wrong reason," Prabhu says. Linda Kah, a geochemist at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville who was not part of the study, calls it a "magnificent effort." Its "big data" approach offers a roadmap for scientists seeking even more ancient biosignatures, she says -- and poses questions that demand further investigation. For example: Does the AI's diminishing returns for the most ancient and degraded samples mean the technique is approaching a fundamental limit of what can be recognized as biotic? Or might older samples instead simply contain more abiotic material because life had yet to fully infiltrate the available environments on the early Earth? Answers could come soon. The team is already planning to test its AI on a broader, more diverse set of samples, including ones from even deeper in Earth's history and from a wider range of extraterrestrial sources. And some interplanetary robotic explorers -- NASA's Curiosity rover among them -- already carry Py-GC-MS instruments onboard, potentially offering chances for otherworldly ground-truthing of the technique. "Studies such as this one take us one step closer in learning about the origin and evolution of life on Earth," says Amy J. Williams, a geobiologist at the University of Florida who was also not part of the work. "They prepare us to address that most fundamental question of whether we are alone in the universe."

[3]

Secret chemical traces reveal life on Earth 3. 3 billion years ago

Researchers from the Carnegie Institution for Science led an international effort that combined state-of-the-art chemical techniques with artificial intelligence. Their goal was to uncover extremely subtle chemical "whispers" of past biology hidden inside heavily altered ancient rocks. By applying machine learning, the team trained computer models to recognize faint molecular fingerprints left by living organisms long after the original biomolecules were destroyed. Seaweed Fossils Offer a Window Into Early Complex Life Michigan State University's Katie Maloney, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, contributed to the project. Her work focuses on how early complex life evolved and shaped ancient ecosystems. Maloney provided exceptionally well-preserved seaweed fossils that are roughly one billion years old, collected from Yukon Territory, Canada. These fossils are among the earliest known seaweeds in the geological record, dating to a time when most organisms were visible only under a microscope. The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offers new understanding of Earth's earliest biosphere. It also carries major implications for exploring life beyond Earth. The same methods could be applied to samples from Mars or other planetary bodies to determine whether they once supported life. "Ancient rocks are full of interesting puzzles that tell us the story of life on Earth, but a few of the pieces are always missing," Maloney said. "Pairing chemical analysis and machine learning has revealed biological clues about ancient life that were previously invisible." Why Early Biosignatures Are So Hard to Find Life on early Earth left behind only sparse molecular evidence. Fragile materials such as primitive cells and microbial mats were buried, squeezed, heated, and fractured as the planet's crust shifted over billions of years. These intense processes destroyed most original biosignatures that could have provided insight into life's earliest stages. Yet the new findings show that even after original molecules vanish, the arrangement of surviving fragments can still reveal important information about ancient ecosystems. This research demonstrates that ancient life left behind more signals than scientists once suspected -- faint chemical "whispers" preserved within the rock record. To identify these clues, the team used high-resolution chemical techniques to break down both organic and inorganic material into molecular fragments. They then trained an artificial intelligence system to recognize the chemical "fingerprints" associated with biological origins. The researchers analyzed more than 400 samples, ranging from modern plants and animals to billion-year-old fossils and meteorites. The AI system distinguished biological from nonbiological materials with over 90 percent accuracy and detected signs of photosynthesis in rocks at least 2.5 billion years old. Doubling the Time Span for Detecting Ancient Life Before this work, dependable molecular evidence for life had only been identified in rocks younger than 1.7 billion years. This new approach effectively doubles the period during which scientists can study chemical biosignatures. "Ancient life leaves more than fossils; it leaves chemical echoes," said Dr. Robert Hazen, senior staff scientist at Carnegie and a co-lead author. "Using machine learning, we can now reliably interpret these echoes for the first time." A New Way to Explore Earth's Deep Past and Other Worlds For Maloney, who studies how early photosynthetic organisms reshaped the planet, the results are especially meaningful. "This innovative technique helps us to read the deep time fossil record in a new way," she said. "This could help guide the search for life on other planets."

[4]

AI Uncovers Evidence of Life in 3.3-Billion-Year-Old Rocks

Earth is roughly 4.5 billion years old. Thanks to a wealth of indirect evidence from isotopes, stromatolites, and microfossils, scientists believe life emerged around 3.7 billion years ago. But direct evidenceâ€"the biochemical recordâ€"only dates back about 1.6 billion years. By combining machine learning with cutting-edge chemical analysis, an international team of researchers has detected biosignatures that significantly extend Earth's biochemical record, corroborating what indirect evidence has long suggested. The findings, published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, include the detection of chemical “fingerprints†left behind by microbes in 3.3-billion-year-old rocks. On top of this, they found chemical signatures of photosynthetic life in rocks as old as 2.5 billion years, extending the chemical record of photosynthesis preserved in carbon molecules by over 800 million years. “Scientists have developed many different ways to infer life in ancient samplesâ€"looking at the textures of rocks, their minerals, the isotopesâ€"but using complex molecules to come up with an unambiguous record of life only extended previously to about 1.6 billion years ago,†co-lead author Michael L. Wong, a research scientist at Carnegie Science’s Earth & Planets Laboratory, told Gizmodo. “We're taking that all the way to 3.3 [billion], so doubling that age.†Wong led the project alongside Anirudh Prabhu, another research scientist at Carnegie Science’s Earth & Planets Laboratory. While Wong specializes in astrobiology and planetary science, Prabhu is an AI and machine learning expert. To understand how this new model accurately distinguishes biosignatures from abiotic materials, you can think of it like facial-recognition software, Prabhu told Gizmodo. The model is trained on GC-MS (gas chromatography mass spectrometry) data. This 3D spectral data looks kind of like a landscape, with peaks, valleys, hills, and other features, Prabhu explained. The model identifies patterns among these features that correspond to biological materials, similarly to how facial recognition software is trained to identify the shapes that make up a person’s eyes, mouth, nose, and bone structure. “We're looking at the entire data[set], and the model is able to pick out specific features that are very key to a sample being photosynthetic or notâ€"or biogenic or notâ€"in a manner that humans just can't do because of how vast the data is,†Prabhu explained. The model is currently able to do this with 90% accuracy, and the researchers hope it will improve as it trains on more data from an increasingly diverse set of samples. This new technique could be a game changer for paleobiologists, allowing them to detect ancient biomarkers even in badly degraded or deformed samples. It’s already opening up a whole new world of opportunity for ancient chemical analysis, and Earth is only just the beginning. The search for ancient life extends far beyond our home planet. Astrobiologists like Wong look for evidence of life elsewhere in the solar system, such as on Mars or Saturn’s icy moons. The fact that the AI was able to accurately detect signs of ancient life on Earth “boosted my confidence that we’re on the right track for developing the kinds of instrumentation and machine learning algorithms that we need to try to find evidence of life in, say, ancient Mars rocks,†Wong said. “I’m full of optimism for the applications elsewhere, beyond Earth.†Wong, Prabhu, and their colleagues chose to train the AI on GC-MS data largely because it is a flight-ready instrument. “It has spaceflight heritage, there’s one of these pyrolysis GC-MS instruments sitting in the belly of the Curiosity rover on Mars right now,†Wong said. The model’s design also prioritizes computational lightweightness and interpretability, which is critical for conducting analyses in real-time as rovers collect geological samples, Prabhu explained. “So you have a rover on Mars or some other planet, it picks up a sample, zaps it, and produces the spectra. You can quickly get a preliminary predictionâ€"a highly accurate, but preliminary predictionâ€"that scientists can use to understand that area and make decisions,†he said. Both Wong and Prabhu hope to see this technology applied across the solar system, and they’ll be seeking NASA partnerships to expand its capabilities and ultimately send it to space. For now, the model will continue to deepen our understanding of the emergence of life on Earth, helping us unravel the mysteries of our origin.

[5]

AI tool can identify chemical signatures of alien life

A new artificial intelligence system takes on one of science's toughest questions: did this chemistry originate from life or not? Built by researchers at Georgia Tech and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, the technology studies meteorites and Earth soils for patterns that might signal biology. The system, called LifeTracer, is a machine learning tool that compares complex mixtures of organic molecules. In tests, LifeTracer correctly distinguished lifeless space rocks from life-bearing Earth samples about 87 percent of the time, using only chemical data. To build that training set, the team led by Amirali Aghazadeh, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at Georgia Tech, measured soluble organics in eight carbon-rich meteorites and ten terrestrial soils and shales. The experts relied on mass spectrometry, a technique that identifies molecules by their mass and fragment patterns. Space rocks and Earth soils both carry rich organic chemistry, so telling life derived molecules from raw chemistry is not as simple as checking one compound. Some abiotic organics, made by nonliving processes in space or on rocks, include amino acids and nucleobases that earlier work has already found inside carbon-rich meteorites. Instead of chasing single molecules, LifeTracer reads the forest of signals that mass spectrometers record as peaks in two-dimensional chromatograms. In this study, the team logged 9,475 distinct fragment peaks in the meteorite extracts and 9,070 in the terrestrial samples. From those peaks, the software builds thousands of features that encode each compound's mass and how long it stayed in each column of the gas chromatograph. A logistic regression, a statistical method that estimates probabilities between two options, acts as the core classifier that assigns each sample to either the abiotic or biotic class. Because many of those peaks come from fragments of the same parent molecule, the researchers clustered them into groups that share similar retention times. Each group acts like a chemical fingerprint, marking a family of molecules that tends to appear in either space rocks or Earth materials. The algorithm then learns which fingerprints push a sample toward the abiotic label and which ones push it toward the biotic label. Once that training is complete, the model can examine a completely new pattern of peaks and decide which side it most closely resembles. Many of the meteorites in the dataset belong to carbonaceous chondrites, older stony meteorites rich in carbon and preserving early solar system material. Earlier work has shown that such meteorites can hold tens of thousands of distinct organic molecules, far beyond what older analytical methods could capture. In LifeTracer's analysis, fragment ions from meteorites tended to leave the chromatograph's first column earlier than those from Earth samples. That pattern means the abiotic mixtures were overall more volatile, so their molecules moved faster through the heated columns. Among the most informative fingerprints were polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), ring-shaped molecules built from linked carbon atoms and hydrogen that often arise in high-energy environments. One simple member of that family, naphthalene, showed up repeatedly in meteorite samples and became the strongest single predictor of an abiotic origin in the model. On the Earth side, one especially telling fingerprint came from a benzene ring with multiple long carbon branches, found mostly in soils from places like Utah, the Atacama, and Iceland. Their structure matches the kinds of long, branched molecules that modern life uses in cell membranes, so their presence boosted the chance that a sample was labeled biotic. Scientists call the chemical clues that might point to life biosignatures, signs that past or present life shaped a planet's chemistry. Many teams now argue that the most reliable biosignatures will come from whole patterns of organics rather than from a single special molecule. "Determining whether organic molecules in planetary samples originate from biological or nonbiological processes is central to the search for life beyond Earth," said Daniel Saeedi, the study's lead author at Georgia Tech. His team designed LifeTracer specifically to work with noisy, incomplete datasets like those planetary missions are expected to return. Sample return missions from asteroids and planets carry only tiny amounts of material, often just grams of dust and rock scraped from carefully chosen sites. Those samples mix organics from many sources, including space chemistry, surface weathering, and any biology that might once have lived there. Future projects such as a Mars Sample Return campaign and Japan's Martian Moons Exploration mission aim to bring back material from places that may once have been habitable. Tools like LifeTracer could help mission scientists quickly sort those mixtures, flagging which ones most closely resemble life-modified chemistry instead of purely abiotic baselines. Because it works on the full distribution of molecules rather than a short list of known biomarkers, LifeTracer could also catch unfamiliar kinds of chemistry that still look organized like life. That broad view will not by itself prove life existed elsewhere, but it can guide closer, slower analyses that dig into specific molecules and isotopes. If scientists can combine pattern-finding tools like LifeTracer with agents that propose and test hypotheses, they may finally have a practical way to search huge datasets for subtle signs of biology. That combination might let future missions treat every returned grain of dust as a potential clue to how life starts, both on Earth and far beyond. Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

[6]

Life may have emerged a billion years earlier than we thought

Earth holds memories far older than humans. These memories rest inside ancient stones shaped by heat, pressure, and time. Many early signs of life vanished as these rocks changed deep within the crust. Yet scientists continue to search for faint signals that survived. A new study reveals chemical traces of biology in rocks older than 3.3 billion years. The research suggests that oxygen-producing photosynthesis began far earlier than expected. The study paired modern chemistry with artificial intelligence. The goal was simple: to read chemical messages left behind by early organisms. The messages exist as small molecular fragments. These fragments persist even when original cells or biomolecules have long disappeared. The team trained machine learning systems to study the chemical profiles of many organic materials. The system learned how life shapes molecular patterns in a way that non biological processes do not. Once trained, the system examined ancient rocks and detected signals that point to life, even in samples older than three billion years. The study shows that life left a more durable chemical trail than once thought. These trails appear as faint patterns inside highly altered rocks. Many earlier models could not read these traces. The new method opens a wider window into early Earth, building on a growing body of work that uses chemical data and artificial intelligence. Previous research showed that organic matter formed by life carries different molecular patterns than material formed through non biological chemistry. The new study extends that idea with a larger range of samples and a more powerful model. Michigan State University scientist Katie Maloney joined the project. She studies early complex life and ancient ecosystems. Maloney contributed rare seaweed fossils from Canada that date back one billion years. These fossils represent some of the earliest known seaweeds at a time when most life stayed microscopic. "Ancient rocks are full of interesting puzzles that tell us the story of life on Earth, but a few of the pieces are always missing," Maloney said. "Pairing chemical analysis and machine learning has revealed biological clues about ancient life that were previously invisible." Her samples helped confirm that the method works on very old fossils as well as younger ones. These fossils hold organic fragments that still reflect the nature of the organisms that once lived. The new study was focused on detailed analyses of more than 400 samples. These samples included modern plants, modern animals, fossil microbes, fossil plants, meteorites, ancient sedimentary rocks, and synthetic materials. The researchers examined each sample using pyrolysis gas chromatography with mass spectrometry. This method breaks organic matter into many small fragments for study. Artificial intelligence then examined these fragments. The models separated biological and non biological material with strong accuracy. The models also identified traits linked to metabolism. These traits included signals from photosynthetic organisms as well as non photosynthetic organisms. The results confirm that even broken and degraded molecular remains still hold a clear biological pattern. Heat, pressure, and chemical changes often destroy full biomolecules. Yet the pattern formed by many fragments still reveals the presence of life. The team found that several samples older than three billion years carry strong signals of biological origin. Some samples resemble microbial material. Others show clear links to early forms of photosynthetic life. This discovery pushes back the evidence for oxygen-producing photosynthesis by nearly a billion years. The method also distinguishes biological organic matter from meteorite derived organic matter. This is important because some ancient rocks contain both types. The ability to separate the two offers strong potential for future space missions. Researchers need to know if a rock from Mars or another world once held living organisms or only non biological carbon from space. "Ancient life leaves more than fossils; it leaves chemical echoes," said Dr. Robert Hazen. "Using machine learning, we can now reliably interpret these echoes for the first time." The combined findings show a pattern through Earth history. Younger rocks contain clear biological signatures. Older rocks contain weaker but still recognizable biological signals. This decline likely reflects increasing molecular damage with age. It may also reflect the presence of some non biological organic matter in the oldest samples. Yet the important point remains. Many Paleoarchean samples still carry patterns that point to life. These results align with earlier work that used morphology and isotopes to study early life. The new method adds chemical strength to those earlier lines of evidence. Together, they show that early Earth hosted a rich microbial world long before complex organisms appeared. "This innovative technique helps us to read the deep time fossil record in a new way," said Maloney. "This could help guide the search for life on other planets." The method may soon combine more types of data. Scientists plan to add isotope ratios, Raman spectra, infrared spectra, and morphological data. Such additions may reveal even deeper details about early life. They may also help detect non-oxygen-based photosynthesis and other ancient metabolic processes. The long term goal is clear. Researchers want to understand how life began, how it changed through deep time, and how to detect it on distant worlds. The new results show that even Earth's oldest rocks still preserve chemical memories of early life - and those memories are now speaking more clearly than ever. The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. -- - Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Scientists use artificial intelligence to identify chemical signatures of ancient life in rocks dating back 3.3 billion years, doubling the previous record for detecting molecular biosignatures and potentially revolutionizing the search for extraterrestrial life.

AI Revolutionizes Detection of Ancient Life

Scientists have achieved a groundbreaking milestone in paleobiology by developing an artificial intelligence system that can detect chemical signatures of ancient life in rocks dating back 3.3 billion years. This represents a significant leap forward, effectively doubling the previous record for identifying molecular biosignatures, which previously extended only to 1.6 billion years ago

1

.

Source: Earth.com

The research, led by Robert Hazen at the Carnegie Institution for Science and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, introduces a novel approach to reading what researchers call molecular "ghosts" left behind by early life

1

. Unlike traditional methods that search for intact fossils or biomolecules, this AI system identifies patterns in chemical fragments that remain after original biological compounds have degraded over billions of years.Machine Learning Meets Ancient Chemistry

The team analyzed more than 400 samples using a pyrolysis gas chromatograph mass spectrometer (Py-GC-MS), which heats samples to over 600°C to break them into volatile fragments

2

. Each sample generated a complex "chemical landscape" containing tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of peaks representing different molecular fragments.Michael Wong, the study's first author and astrobiologist at Carnegie Science, likens the instrument to "a really fancy oven that not only bakes your cake, but tastes it for you, too"

1

. The team then employed a random forest machine learning model to identify patterns that distinguish biological from non-biological samples.After training on 75% of the samples, the AI achieved over 90% accuracy in distinguishing between biological and abiotic materials when tested on the remaining samples

3

. The system successfully identified biological signatures in rocks as ancient as 3.3 billion years old, nearly twice as old as previous biomolecular signatures preserved in ancient rocks.

Source: Gizmodo

Photosynthesis Evidence Pushed Back 800 Million Years

One of the most significant discoveries involves evidence of photosynthetic life in rocks dating to 2.5 billion years ago, pushing back the molecular signature of oxygen-producing photosynthesis by more than 800 million years

4

. While geochemical evidence for photosynthetic life around this time period exists from the sudden explosion of oxygen it produced, preserved evidence of these organisms' molecular machinery has been scarce until now.Katie Maloney from Michigan State University, who contributed exceptionally well-preserved billion-year-old seaweed fossils to the study, emphasized the significance: "This innovative technique helps us to read the deep time fossil record in a new way"

3

.

Source: ScienceDaily

Related Stories

Implications for Extraterrestrial Life Detection

The breakthrough has profound implications for astrobiology and the search for life beyond Earth. The AI system was specifically designed to work with flight-ready instrumentation, as similar pyrolysis GC-MS instruments are already deployed on Mars rovers like Curiosity

4

."Our approach could run on board a rover -- no need to send samples home," Wong explained

2

. This capability could enable real-time analysis of geological samples on Mars or other planetary bodies, providing immediate insights into potential biosignatures.A separate but related development comes from researchers at Georgia Tech and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, who created LifeTracer, another AI system that achieved 87% accuracy in distinguishing lifeless meteorites from life-bearing Earth samples

5

. This complementary approach focuses on analyzing complex mixtures of organic molecules in meteorites and terrestrial samples.Overcoming Ancient Rock Degradation Challenges

The challenge of detecting ancient life stems from Earth's dynamic geological processes. Over billions of years, tectonic activity buries, crushes, heats, and cools sediments, obliterating most original biosignatures

1

. Beyond approximately two billion years, no pristine, unaltered Earth rocks are known to exist, making any potential sign of biology extremely difficult to detect.The new AI approach circumvents this problem by focusing on degradation patterns rather than intact molecules. As Hazen explains, "Our method looks for patterns instead, like facial recognition for molecular fragments. Think of the burnt Herculaneum scrolls that AI helped 'read.' You and I just see dots and squiggles, but AI can reconstruct letters and words"

2

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[2]

Related Stories

NASA Employs AI and Machine Learning to Enhance Mars Exploration

17 Jul 2024

AI-Powered Discovery: Mars Impact Crater Reveals New Insights into Planet's Interior

04 Feb 2025•Science and Research

AI and Robotics Revolutionize Chemical Analysis: FSU Researchers Develop 99% Accurate Image-Based Identification Tool

20 Mar 2025•Science and Research

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic sues Pentagon over supply chain risk label after refusing autonomous weapons use

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round as questions swirl around AI bubble and profitability

Business and Economy