AI in Filmmaking and Art: A Creative Evolution or Disruption?

6 Sources

6 Sources

[1]

Could AI make a Scorsese movie? Demis Hassabis and Darren Aronofsky discuss

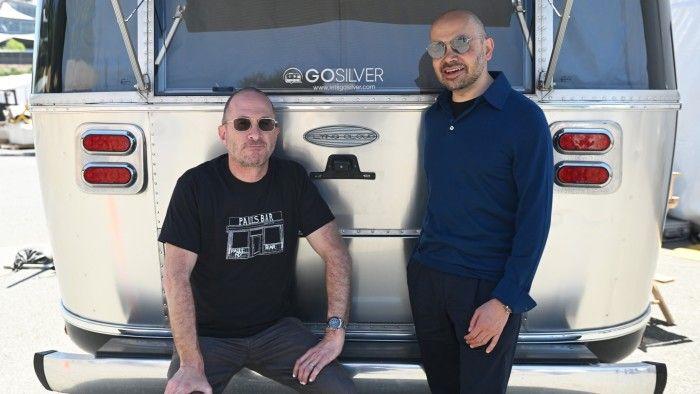

Demis Hassabis and Darren Aronofsky met in 1999 when they were invited to speak at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London about the future of storytelling. At the time, Hassabis was a video game developer; today he is CEO of Google's DeepMind AI lab and a Nobel laureate in chemistry. Aronofsky had released his debut feature Pi in 1998 and would go on to direct the Oscar-winning Black Swan and The Whale. Now, his new film company, Primordial Soup, is joining forces with Hassabis and DeepMind to produce short narrative films using AI. Three are already in the works. Demis, why is using AI in filmmaking interesting to you? Demis Hassabis: It stems from my games background. I started by doing game design and programming. That's how I got into AI, actually. I love this fusion of technology enabling creativity. During the golden era of games in the 1990s, we were exploring a whole new art form, one which fused the best of technology with the best of design. We didn't just make games, we were inventing whole new genres, such as the best-selling simulation game Theme Park which I co-designed and programmed in 1994, aged 17. I see the work I'm doing now with AI and these AI tools that we're building [being used] for creativity. Darren, what's the idea behind your new film company Primordial Soup? Darren Aronofsky: "Make soup, not slop" is the working model right now. All of us have seen things [generated by AI] that we've never seen before, but for some reason they kind of go in your head and then they just dissipate and you don't really quite remember them. I was wondering why that was, and I think what's missing is storytelling -- the emotion to the slop. And that's why I started to think about how we can use this incredibly powerful technology to aid our storytelling. I know if I was 27 right now, trying to make my first film, it would be me and five friends in a room with computers trying to figure out how this all works and what type of stories we can tell. Demis, besides your video game background, are you also a movie fan? DH: Massively. This is why Darren and I bonded so well. Science fiction was a big inspiration for me from the beginning, including probably my favourite film Blade Runner. I loved the music and aesthetic but also its deep exploration of artificial consciousness, and what it means to be human. I have many friends who are in the film business and my whole family is on the creative side. My father is just about to stage an opera that he's written in his retirement, my sister's a composer and pianist -- my whole family is in the arts. I'm the black sheep working in science and games. Darren, you've released a trailer for the short film 'Ancestra', directed by Eliza McNitt. What part did AI play and where do humans come in? DA: Human performance is still amazing and something that we wanted to capture for this piece. But Eliza's film is "inspired by the day she was born" -- there were many things in her vision that were completely unphotographable and purely imaginative. The AI models have to be pushed to imagine as well, and they're creating stuff that's never really existed before. The press materials for 'Ancestra' mention input from members of the Screen Actors Guild. AI was a big concern during the Hollywood strikes in 2023. Have you spoken to the unions about what you're doing? DA: We have producers who talked to them. But the unions are all leaning into how they're going to work with this technology. There's an unbelievable amount of workers, different types of artisans and technicians that have come together to work on "Ancestra". I should probably do a count, but I'm sure the crew list is huge, almost like the size of a normal feature film for a short film because the tools and the technology are brand new. Many people in Hollywood are freaking out about AI. Should they be? DA: For storytelling, technology replacing human involvement is in the realm of science fiction. Being on set and seeing how it takes hundreds of different types of artists and crafts people to come together to make a single moment, itself all anchored upon the performance of a real person who's totally unique and then has to carry that story over a length of time -- it's a very complicated thing to do. Demis, what's in it for DeepMind and Google? DH: The creative process is going to change a lot in a couple of years, and that's exciting. So we want to provide the right tools for creators. We're getting input from musicians and filmmakers like Darren [DeepMind's other collaborations include Donald Glover and Jacob Collier] to tell us what they need and what sorts of things they want the models to be able to do. For the average user, this will come to things like YouTube in some way. But what's exciting from a research perspective is: if you want your AI system to understand the world around you, it needs to understand the physical world. What does the model know about intuitive physics, about lighting and gravity and material behaviour of liquids? That's the sort of understanding you would need. DA: It's like the early days of hip hop and sampling when there were just so many possibilities of what music could be suddenly. Demis, do you think in 10 or 15 years an AI will be able to develop a particular vision or a visual style the way filmmakers do? DH: Currently, these tools are not capable of making up new starts. They're more extrapolations of what's already known. Can these systems actually come up with new conjectures, not just solve an existing one? The answer right now is no. So there's clearly still something missing from these systems, out-of-the box thinking or true invention, that the great creatives, whether they're scientists or artists like Einstein or Picasso, can do. DA: What do you call that? Intuition? DH: I would call it "true invention". Humans have analogical reasoning -- it's like, oh, I've got all this knowledge, and then I found some underlying pattern in this other area that this could map to. Our AI systems are still not capable of that. But one day they might be. Lots of people are researching these things: can you codify curiosity? I think that kind of out-of-the-box invention requires a few extra skills beyond just pattern matching. It requires good judgment, good taste. That's what separates good scientists from great scientists, and I'm pretty sure good artists from great artists. If you're lucky in science, which I know a lot about, they always say, I can smell this idea is a good one. And we don't have that yet in these AI systems. DA: The last time Demis and I hung out, I asked: how far are we from a masterpiece [comparable to one] by Martin Scorsese coming out of AI prompts? He wasn't sure that would ever happen, but something's happening with these images that's exciting. Someone's going to figure out how to tell stories with this in a new way.

[2]

I'm skeptical about AI's impact on creativity - Where does humanity go when machines join in?

When AI enters the creative process, what changes - and what remains human? AI is destroying creativity. That's the view many people hold. And, after months of reporting on AI, it's largely been mine too. The flood of generative content, the erasure of authorship, the feeling that these tools are mimicking something sacred without truly understanding it. It's been hard not to feel like something really important is being lost - especially when I found out my book was used to train Meta's AI. But recently, I've been speaking to people who aren't buying into the AI hype. But they're not writing it all off out of fear either. They're sitting in the messy, complicated middle. And they're creating great things. These are people working directly with AI in creative fields, while still holding the human element as essential. And they've made me ask: what if AI doesn't signal the end of human creativity? What if it's a difficult, uncomfortable but necessary evolution? Personally, I'm still wary. I probably always will be. But talking to people who are engaging thoughtfully with how AI might augment, not replace, the creative process has been unexpectedly refreshing. Maybe even hopeful. Anything to ease the creeping sense of creative despair I've been feeling lately. So, here's what they had to say. Lucas Stanley, a Senior AI Creative at digital marketing company Jellyfish, explains: "Seeing AI play a role in almost everything we do isn't just a possibility, it's the concrete future. But just because we can see where it's going doesn't mean we're there yet." He describes the current landscape of AI in creative work as powerful but clunky. Sure, it's full of potential, but far from effortless. "Making genuinely good creative work with it is tough. It rarely gives you what you need the first time." That's why, he explains, human input is still essential. "A big part of my job is finding ways to guide, and sometimes really struggle with, these technologies to get them to produce what we need," he says. "It's a process of establishing a direction, then a lot of shaping, refining, and what I think of as 'polishing, tightening, and regenerating' to arrive at something genuinely useful." I like this because it cuts through the idea that AI-generated work is some kind of effortless magic. It's not. It's still craft, just one that needs shaping in new ways. For Rasmus Adler Wahlberg, co-founder and CEO of Multiply, the real promise of AI lies in hybrid collaboration - not automation and not replacement. Multiply is building what they call a "Creative Operating System" for agencies and teams, where AI and humans work together on strategic, analytical and creative tasks. "We are building a system that embeds their unique expertise, culture and methods in AI agents and workflows to enhance what makes them unique instead of watering it down," Wahlberg tells me. "It is becoming increasingly clear that AI is great at some things and we, as people, at others," he says. He believes in using AI as a "creative sparring partner," not a substitute. "The real magic happens when creative people and intelligent agents co-create in flow," he says. "Where creative humans and artificial intelligence become more than the sum of their parts. Creative Intelligence, as we like to call it." The aim isn't to automate the creative process. It's to build new systems that amplify what people do best. Stella Achenbach, founder of the web3 educational project ALANA, approaches AI with a background that spans fashion, digital design, gaming, and blockchain. She's not anti-AI - but she is deliberate. "While I work with AI, I try to do it very consciously," she says. That means choosing open-source tools over centralized platforms, asking whether AI is truly needed before using it, and thinking carefully about the broader systems we're helping to build. "It is also important to understand AI as a tool extension, not a replacement," she adds. "AI is not self-sufficient. It requires millions of people to tag data points so it can 'read' information, for example." For Achenbach, many of the problems we're seeing with AI and creativity could be addressed with more conscious design - and with blockchain technology, which she sees as a necessary safeguard for ownership, transparency and accountability. When I mentioned the controversy around Meta's AI training data and the use of books from LibGen, she was clear: "If every data point they scraped had been tagged with a creator, we could have built incredibly cool incentive mechanisms on top of the ownership of that data. But they didn't want that because of their greed, not because it was impossible." "Blockchain is the natural safeguard against AI to keep it - and the companies behind it - in check," she says. "The other perspective is that users need to self-educate more and better. Blindly using centralized platforms in this day and age has become dangerous and will become more dangerous as we proceed." One thing that stood out most in these conversations was the attention paid to joy, collaboration and actual creative flow. These are the intangible things that draw people into creative work in the first place. "For my teams, my personal north star is to make things feel creative and to build processes that make working on creative projects fun," says Stanley. "The idea of individuals just prompting away by themselves isn't very attractive to most creative people who really flourish in collaboration." So his team is actively building AI workflows that are collaborative from the start, which includes working sessions, real-time feedback, shared spaces for both human and AI contributions - even room for the bloopers. "We post the mess-ups and misgenerations because, honestly, they're often hilarious and a great learning tool," he says. "Seeing people interact with AI in that kind of open, team-based context is completely different. People aren't scared anymore; they're having fun and being genuinely creative. And that's what we're all in the creative industry to do." Crucially, Stanley believes the people who will thrive in this space are those grounded in a creative craft. "The tools and mediums change over time, from traditional methods to digital, and now to AI. But the fundamental human need to create and express stays the same," he says. "Often, the people creating the most interesting work with AI are those who have a background in a traditional craft, because they've already gone through that process of learning how to express themselves." I wish I could say I now feel completely optimistic. But I'm still not convinced that the scale and speed at which AI tools are developing can be managed. Or that we'll have the time, resources and conversations we need to protect what makes human creativity so vital in the first place. But it is comforting to know there are people thinking more clearly and hopefully than I am right now. And building the tools and systems they want to see. Because building with collaboration, care, safeguards and creative energy is no small thing. These aren't the qualities that usually make headlines. The narratives tend to swing between two extremes: breathless hype that frames AI as a kind of magic or total collapse where creativity is swallowed whole and there's nothing we can do about it. But in between those poles, there's this slower, quieter work - people designing systems, making things, asking better questions. That middle space might not be dramatic enough to dominate the conversation. But it's where the real future is being built. And for the first time in a while, that gives me a bit of hope.

[3]

When AI-generated art enters the market, consumers win -- and artists lose

In 2024, the New York Times sued OpenAI for copyright infringement, claiming the company had used the newspaper's content to train its algorithms without permission or payment. The case, one of several AI-related copyright suits, is another sign of fast-changing times. "We're in this transition in the economy between human-centered production and a more generative-AI-centered production," says Samuel Goldberg, an assistant professor of marketing at Stanford Graduate School of Business. "But we train AI models on human outputs, especially in creative industries like art, writing, music, and images. Those human outputs become the inputs." A central component of the Times lawsuit, Goldberg says, "ultimately boils down to this question of whether AI output is a substitute for the human inputs it uses." That question is also at the center of a new study by Goldberg and H. Tai Lam of the University of California, Los Angeles, which examines what happened when an online marketplace allowed AI-generated art to compete with images made by people. The paper is available on the SSRN preprint server. "We have some idea of how GenAI might impact productivity, but ultimately, what this productivity means for the market, competition, and demand is an open question. We wanted to see how markets react to the introduction of these types of technologies on both the supply and demand sides," Goldberg says. The results were striking: Once generative AI (GenAI) entered the market, the total number of images for sale skyrocketed, while the number of human-generated images fell dramatically. On the flip side, consumers showed a taste for the influx of AI-generated images, choosing GenAI images over human-generated ones. "Our results show GenAI is likely to crowd out non-GenAI firms and goods," Goldberg and Lam conclude. Clearly, this is unwelcome news for creators. Yet this brought increased competition, quality, and variety on the platform -- benefits for buyers. These findings provide a glimpse into the future of markets for creative goods, including music, novels, and movies. Image of a changing market To study the impacts of AI-generated content, Goldberg and Lam worked with data from a large online platform that provides consumers with access to nearly 500 million images and videos. "The buyers might be writers who write blog posts or articles who want images for the piece, or a business that needs an image for the pamphlet," Goldberg says. On the other side are the sellers, or the producers of those images -- artists, photographers, and illustrators. These were mostly individuals or smaller firms, as Goldberg notes, "Maybe a group of two or three people, but some larger firms that produce tens of thousands of images and have many, many photographers working for them." The study's sample included over 3.2 million unique images and 62,000 artists and producers. Human-generated images were the only goods on the platform until December 2022, when it began allowing images made with generative AI and requiring that they be labeled as such. This change enabled the researchers to "look at the before and after," as Goldberg explains. "After we see generative AI enter, we see artists making decisions about whether or not to adapt and how to produce their images, if they want to use AI tools or not." The platform also prohibited AI images from including any references to brands and from being offered on markets primarily for editorial use. That allowed for a cleaner comparison between markets on the platform where AI was allowed and those where it wasn't. The researchers created measures of content and quality of every image studied, partly to understand how similar or different they were. "That way, we can compare AI images to non-AI images and whether the AI images contribute variety to the platform," Goldberg says. The introduction of AI images significantly changed the dynamics for sellers and buyers on the site. The researchers saw a "huge increase in images arriving on the platform after the introduction of generative AI," Goldberg says, 78% more images per month than in markets without AI images. "This was driven almost exclusively by generative AI production." The number of producers also grew significantly: There were 88% more active firms per month in markets with GenAI images than in markets without AI images. The increase was driven by sellers using AI and was accompanied by an additional 23% drop in non-AI artists. "We see an exit of non-generative-AI artists from the site," Goldberg says. Alongside these shifts, image quality improved overall. "There was also quality improvement specifically among non-AI images," Goldberg says. "Competition increased, and the non-generative-AI artists who left the platform were probably lower-quality artists. The good ones stay and the bad ones leave. That's traditionally what you hope competition would do." The AI images also added variety to the platform. "They're not just copies of one another or of existing images," Goldberg says. "That's better for consumers." A complex picture for creators Meanwhile, total sales rose by 39% after AI images arrived, but purchases of non-AI images dropped. This implies AI images compete directly with non-AI images. "Our evidence suggests that GenAI images look like substitutes for non-AI images," Goldberg says. "Our findings seem to be good news for consumers," Goldberg says. "There's more variety on the platform and some quality benefit, and they're purchasing more." "For producers, it's more tricky," he continues. Some sellers have turned to generative AI and may be selling more images than before. "But if you were not as competitive before GenAI, you're being squeezed out of this platform. Is that a bad thing? I'm not sure." A more subtle issue is the potential diminishment of human creativity due to the sudden flood of generative AI. "We as a society believe that art created by humans is somehow better than art created by machines," Goldberg notes. "So one question you might ask is whether we're at risk of these markets being completely dominated by generative AI, squeezing humans out. That's a real policy concern." Still, he and Lam conclude that their findings do not support banning the use of GenAI in creative goods. Considering its benefits to consumers and the market, the challenge, they say, is "ensuring equitable access to GenAI technologies and non-AI artists." And that New York Times lawsuit against OpenAI? This research has some implications for the case (though Goldberg emphasizes he's not an attorney): "Our paper suggests the generative AI outputs are substitutes for the human-created inputs, and lawyers are arguing that creators of images used to train AI should be compensated for that."

[4]

I went to an AI art conference expecting empty hype - I never expected to be creatively recharged

The Freepik Upscale AI conference showed how AI can be used for art. Like many creatives, I've watched the rise of AI art with a mix of curiosity and concern. For years the art I've loved, and struggled to make, has been tactile and intentional - pencil to paper, stylus to screen. The idea that an AI model could churn out art in seconds felt reductive. Visiting the Freepik Upscale AI conference in San Francisco I was hesitant and but also intrigued by prospect of learning why and how AI could be used creatively. I was ready to meet a room full of over-promises and underwhelming results, a crowd eager to love bad Ghibli memes. Instead, I found a glimpse of something real and genuinely creative; a tangible future that includes AI art and filmmaking. Not a gimmick, not a tech demo dressed as innovation, but a genuine evolution in how we create and experience art. I've previously met artists like Martin Nebelong who show how using AI can speed up workflows but the speakers and creatives at Freepik Upscale AI conference revealed working faster and cheaper isn't a focus, finding a new art form is more important. And that stood out. The reasons to use AI for artists and designers isn't about doing more for less, crunching numbers, but about starting on the first rung of a new artistic ladder. Held in the SFJAZZ Center gallery-like space, an atmospheric venue humming with nervous energy (and relentless espresso), the Freepik Upscale conference was about more than hot trends and hype. What I experienced was a rethink of what creativity could look like when technology isn't the end, but the means. When artists get to use AI image and video models to experiment and not demand a finished final project from prompts alone, then something interesting happens. Andrea Trabucco-Campos, a graphic designer and Pentagram partner, grounded the conversation where it belongs - in history. He didn't preach about disruption and faced-up to AI's biggest issue - a lack of originality - from the outset, pointing out human-made art is a mish-mash of influences; design building on past trends. Andrea spoke about craft. His talk centred on Artificial Typography, a book that explores how AI "misreads" typefaces and how those misinterpretations become creative opportunities. Distorted ligatures, broken symmetry, moments of accidental beauty and yes, mistakes and misunderstandings by the AI model, can all be harnessed to create something new. Here's the key: Andrea doesn't accept the output at face value. He curates. He edits. He works through hundreds of generated variations to find a single compelling form. His work reinforced what I've always believed, that the artist's eye, the taste, the decision-making, still belongs to the artist and it's something AI can't replace. That shift in perspective continued with Jason Zada from Secret Level. Jason's studio was behind the Wu-Tang Clan's Mandingo, a short film generated entirely with AI tools, from casting, environment design, lighting and animation. It's ambitious, bold, and yes, still imperfect. But it marks a significant moment: a filmmaker using AI to realise cinematic ideas that would once have needed a studio budget. Ahead of his talk Jason spoke to me about TRON and Mary Poppins, the creative milestones where new technology pushed storytelling forward. "AI is waiting for its TRON moment," he told me. Jason is not chasing novelty. He's aiming for a breakthrough, and the real power of what he's building isn't really about automation or replacing artists (he hires artists to work on his films), it's about access. Ideas that used to die in notebooks can now be visualised on a laptop and brought to fruition. Jason's talk also revealed the broader ambition Ai filmmakers should be aiming for - rather than the low-hanging fruit of 'Family Guy as real people' Jason says AI should be used for building worlds that have never been seen before; a small team can now make the music, the film, design the toys and create the video game using AI. What I really found interesting? Jason physically rolled his eyes at the thought of AI Ghibli memes and endless fake movie trailers that riff on Star Wars - like many here he wants to use AI to create original worlds, not remix the past and create "low hanging fruit". Henry Daubrez followed, and his approach might be the most aligned with how you or I have always worked and sort to create art. He treats AI as part of a broader pipeline, mixing Imagen 3 and Veo 2 images and clips with Blender, Photoshop, Premiere Pro and other traditional apps. His approach centres the use of AI on artistic skill, with AI used as a new space to experiment. He remains focused on the fundamentals of filmmaking: pacing, story, emotional resonance and says AI can't be a shortcut achieving something that stands out. "AI films need to be films first," he said, and while it feels obvious the idea is simple but essential: the toolset means nothing if the intent isn't clear. Henry's work proves that AI can be integrated into traditional workflows without compromising vision. The human voice still leads, the new technology just extends its reach. Visual design director GMUNK - Bradley G Munkowitz - echoed many of the themes and approaches I was hearing; AI isn't the answer its just part of the bigger question. GMUNK isn't shy about using new technology in his art, whether its using robotics and projection mapping for short film Box or using Cinema 4D to design animate TRON: Legacy's hologram UI sequences. If anyone could challenge my ideas of originality in AI, it was GMUNK. His process is grounded in authorship, using his own drone footage and infrared photography with Stable Diffusion-made coral textures; he refined and animated the results in a mix of AI and traditional apps like DaVinci Resolve. There's nothing generic about his work. It's layered, considered and personal. What GMUNK made clear is this: creativity in AI isn't about the model, it's about the content you feed it, the choices you make and how you shape the outcomes. The artistry isn't erased, it's amplified. I left the conference with questions that are still unanswered, about ethics, authorship and where this all leads, but I also left with clarity. The conversation isn't about AI replacing creativity, it's about how it reshapes the process. It's not about using prompts creating a finished project, or replacing artists or making something for less, that simply leads to the low-hanging fruit so hated by everyone. For me, every speaker showed how AI, when used intentionally, doesn't dull artistic vision but sharpens it. Ideas can be pushed further, faster. AI can enable you to iterate in hours what once took days. More than anything, AI opens doors to creative territories we haven't had the time, tools or freedom to explore yet. I came in ready to tut and demand answers to big questions on copyright abuse - interestingly, everyone attending believes AI companies need to address this - but I left wanting to experiment and discover what AI can actually do. The future of creativity doesn't look like machines and algorithms slot-maching art in a vacuum. It looks like artists - designers, filmmakers, animators - using new tools to tell different stories. And that, to me, feels a lot less like a threat, and more like an opportunity.

[5]

"Tools evolve, the eye doesn't" - why AI art still needs artists

Freepik CEO Joaquin Cuenca explains why AI can't, and shouldn't, do everything. The sweeping rise of AI and AI art and video in particular has left many artists reeling, struggling to square the circle of how to create art in a new era where, perhaps, an AI can do it all. It didn't help that AI got where it is off the backs of the work of creatives. Freepik CEO Joaquin Cuenca Abela is candid about the industry's missteps. "Honestly, part of the blame is on us, the AI industry," he says. "We trained models on everything under the sun. The outcome was unknown. But it worked. And now we have to rebuild trust." That must include acknowledging the concerns of creators who've seen their work scraped, mimicked, or marginalised. Joaquin believes the way forward is through transparency, collaboration, and a focus on what only humans can do. But we are where we are, and many artists are finding creatives uses of AI, but even Joaquin tempers expectations and offers some reassurance to artists who are finding where they fit in. "AI can help you tell stories. But it won't tell you what story to tell," he says. "That still comes from being aware of the world, understanding what matters to people, and putting that into your work." And that, he believes, is where the future of creativity lies, not in mastering tools, but in mastering meaning, a sentiment OpenAI's Chad Nelson told me too. "Tools evolve," reflects Joaquin. "The eye doesn't." For context, Joaquin tells me, during Freepick's Upscale Conference, the emergence of generative AI looked like a huge, terrifying wave threatening to sweep away the free stock image business he'd spent years creating. He's been on the other side of the equation, struggling to understand what AI means and how to survive. "It looked like it was going to destroy us," he admits. "But we asked: how can we help our users use this tool to do something new?" Rather than resist AI, Freepik leaned in. "We started, very naively, putting Stable Diffusion on our website," Joaquin says. "And then we iterated. And it has worked very well. We're growing more than ever." The company's pivot wasn't just technical, it was cultural. For Joaquin, the core question became how to empower creatives with tools that expand, not replace, their vision. That shift has broadened Freepik's audience far beyond its traditional base of freelance graphic designers. "Now we're seeing filmmakers, photographers, even architects using the platform," Joaquin notes. "Three years ago, a photographer had no reason to come to Freepik, but now, with tools like Magnific AI for retouching, they do." Generative AI isn't just making creative work faster, it's changing what's possible. Joaquin compares its impact to the advent of photography, which democratised the act of capturing reality. "When the camera was invented, people said it would kill painting," he says. "But it didn't. It just changed what people painted." Similarly, AI allows creators to tell stories that were previously impossible, not just because of budget constraints, but because traditional tools demanded too much precision or effort for fleeting moments of impact. "3D was supposed to be faster, but in many cases, it became slower and more expensive than just filming," Joaquin explains. "AI allows you to cheat, to create something visually compelling without modelling every detail. That's liberating." Perhaps the most transformative effect of AI is not on what creatives can do, but who can afford to do it. Joaquin sees AI as the next phase in a long pattern of democratisation. "Stock images used to cost $500, only books and TV could afford them," he says. "Then Shutterstock brought it to $10, and we brought it even lower. That's when people started using images for social media." Now, with AI, entirely new use cases are emerging. "You can create a YouTube ad for just 300 people. That wouldn't have made sense before," Joaquin says. "But now it does." He sees applications from high-end production houses to small businesses. "My wife used to run a café. She spent an hour every night designing posts for social media. With a little context - it's Mother's Day, it's a family place, we offer discounts - AI could do all of that for her." For Joaquin, one of the most exciting shifts is how users interact with design tools themselves. Traditionally, design has been trapped on the desktop, requiring time, the cost of hardware and complex software. "Gen AI gives you a new UI," he says. "It's like talking to a designer. You describe what you want, you iterate, and you get results." That conversational approach doesn't eliminate the need for expertise, especially in complex workflows, but it does free up creativity for quick, emotional storytelling. "Great photography isn't about knowing your camera," Joaquin says. "It's about having the eye, knowing what matters and how to tell a story. That doesn't change." As AI image generation becomes commoditised, "you'll go to Google or ChatGPT and get an image for free", Joaquin believes the future lies in building richer, more collaborative workflows. "When you need to share with colleagues or iterate on ideas, that's where our platform comes in," he explains. "We're not designing for a billion casual users. We're designing for tens of millions of professionals." Freepik is already testing features that reflect this shift, from 3D asset creation to "infinite canvas" design spaces, to workflows built around collaboration and customisation. "We launch features, see if people use them, and if they don't, we kill them," Joaquin says. "It's always about the users."

[6]

Why AI means anyone can be a filmmaker not just Hollywood insiders

Director Jason Zada says tools like Google Veo 3 unlock storytelling for everyone. The film industry is no stranger to transformation. From practical effects to digital wizardry, every generation of filmmakers has had their revolution. But according to director and creative technologist Jason Zada, we're not just witnessing an evolution, we're standing on the cusp of an AI-powered content renaissance. Jason isn't new to filmmaking - he directed the 2016 film The Forest starring Game of Thrones star Natalie Dormer - but it's with his viral marketing and music videos, such as the Elf Yourself campaign and the interactive horror Take This Lollipop where he found his voice. Now as founder of Secret Level, the next-generation entertainment was responsible for Coca Cola's AI Christmas commercial, Jason is obsessed with the potential of generative AI for world building and telling new kinds of stories. It's a similar message I heard from Freepik's CEO Joaquin Cuenca, who argues AI still needs an artist's eye to have impact. Speaking with the creative director at Upscale Conf by Freepik, who just revealed Wu-Tang Clan's new AI-made music video, the theme of our conversation is clear: AI is not replacing creativity; it's redefining the way we wield it. "For us, pre-production is the new post-production," Jason says, describing how AI tools now enable creators to visualise finished scenes with stunning fidelity before a single frame is shot. "You can really see how it looks down to the pixel... Having worked traditionally, you never really get to see what it looks like until you're on set, and even then, it's post where it all comes together." In the past, storyboarding, scouting, and previs work were long, laborious processes. But Jason's studio is now leveraging gen AI art models, Google's video AI Veo 3 (Veo 2 was used for current projects), and GPT-based assistants to create high-resolution animatics that allow for real-time iteration. "There's a fluidity that happens in AI production. It's like, 'yeah, I don't like this shot anymore, let's find a different shot,'" he explains. "Historically, that would mean reshoots, and be very expensive, if not impossible." Jason's insights cut through the noise in a debate often fuelled by anxiety over copyright theft and job security. AI won't make creative professionals obsolete argues Jason, but it will shift the dynamics. "We employ about eight to 20 artists per project. Compare that to a traditional 150-person crew. And yet, the scale and fidelity of what we're producing is on par with much bigger productions," he says. The comparison to the model-making days of early visual effects is apt: "Back in the day there were people that made and painted models. Then it went to computers, yes, it replaced some jobs, but it also created the modern VFX industry. I think we're going to see the same thing with AI." AI's greatest gift to filmmakers, Jason believes, is speed. "We're working on an animated feature film that traditionally would take three years. We could do it in nine months to a year." For Jason, this isn't about slashing budgets or cutting corners, it's about creative freedom. "[Despite what you're led to believe] AI is not free, it's not cheap, but it is more efficient," he says. "With that efficiency comes a revolution in content creation. We're going to see more people making more content because the price barriers are lower." The result? A storytelling boom. "We consume entire seasons in two days. Streamers need more content. And this technology means we'll never run out." Jason's vision extends far beyond the frame. He talks about "story worlds" rather than films - cross-platform ecosystems where music, toys, podcasts, and episodic content coexist. "I published an album on Saturday. It was on Spotify by Monday. That's insane. And now, that world can feed into a film, into an animated series, into anything," he says. "The lines are blurred. We're not media-specific anymore." At the core of this new tech is prompting. Jason treats it like directing. "When I'm on set, I'm prompting my crew. I want it moody. I want it to look like this or that. With AI, it's the same - it's just words now. The more you can get what's in your brain out, the better." His team uses GPT to brainstorm character names, generate plot outlines, or even sketch early treatments. "It never writes the final script," he clarifies, "but it gets you thinking fast." On the visual side, they've trained models on specific artist's work, with permission, he stresses, to retain originality (he hires digital artists to work on projects alongside AI). "That way we get original art," he says. "We're using AI ethically, with artist input, to create something entirely new." One common critique of AI is that it just remixes old and existing images, styles and ideas. Jason doesn't disagree, but he challenges the idea that remixing is inherently bad. "We've been copying each other since the dawn of time," he says. "Tarantino is a remix artist. Artists steal from artists. Your brain is a computer full of things you've seen. AI's the same - it's just faster." Still, he bristles at lazy prompting. "If you prompt 'Star Wars' and put it out, you've basically ripped off decades of IP. Just because you can doesn't mean you should." Instead, he calls for creative prompting. "When Midjourney first came out, you could type in 'shrimp tree' and get something you've never seen before. That's what I want to see more of." Could the next Spielberg emerge from this world of pixels and prompts? Jason isn't sure, but he's hopeful. "People used to ask that when digital video came along. We all have 4K cameras in our pockets now. But AI might be different." What's clear is that the next wave of auteurs may not come from film school, they might come from anywhere. "I always ask people what they did before. 'Oh, I was a stockbroker.' 'I was in finance.' Now they're making incredible stuff. That's kind of amazing." Jason is the first to admit we're in uncharted territory. "We're still experimenting. Last year was our first full year in AI production, and by December, it felt like we'd gone from one solar system to another." What's next? "I think we'll hit a people problem," he says. "There's just not enough talent trained in this yet. It's like ILM at the beginning. Over time, more shops popped up, more people trained. But right now, there's a shortage of top-tier AI creators." Until then, he'll keep exploring. "I've always run toward new technology," Jason says with a grin. "We're just going to keep integrating, figuring it out, and experimenting, because it's not about replacing creativity, it's about expanding what's possible."

Share

Share

Copy Link

An exploration of AI's impact on filmmaking and art, featuring insights from industry leaders and creators on the potential and challenges of integrating AI into creative processes.

AI's Integration into Filmmaking and Art

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into creative industries is sparking both excitement and concern among artists and filmmakers. As AI tools become more sophisticated, industry leaders are exploring ways to harness this technology to enhance creativity rather than replace human artists

1

2

.Collaboration Between AI and Human Creativity

Source: FT

Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google's DeepMind, and filmmaker Darren Aronofsky are collaborating on short narrative films using AI. Aronofsky emphasizes that AI is not replacing human involvement in storytelling but rather augmenting it. He states, "Being on set and seeing how it takes hundreds of different types of artists and crafts people to come together to make a single moment... it's a very complicated thing to do"

1

.Lucas Stanley, a Senior AI Creative, describes the current landscape of AI in creative work as "powerful but clunky." He stresses that human input is still essential in guiding AI tools to produce useful results. "A big part of my job is finding ways to guide, and sometimes really struggle with, these technologies to get them to produce what we need," Stanley explains

2

.AI's Impact on the Creative Market

A study by Samuel Goldberg and H. Tai Lam examined the effects of introducing AI-generated art into an online marketplace. The results showed a significant increase in the total number of images available, with AI-generated content becoming popular among consumers. However, this led to a decrease in the number of human-generated images and the exit of some non-AI artists from the platform

3

.New Possibilities in Filmmaking

Source: Creative Bloq

Jason Zada from Secret Level is using AI tools to realize cinematic ideas that would have previously required substantial studio budgets. His work on projects like Wu-Tang Clan's "Mandingo" demonstrates how AI can be used to create original worlds and expand creative possibilities

4

.The Role of Human Expertise

Despite AI's capabilities, industry experts emphasize that human creativity and expertise remain crucial. GMUNK, a visual design director, and Henry Daubrez, a filmmaker, both integrate AI into their workflows but stress the importance of artistic vision and storytelling fundamentals

4

.Related Stories

AI as a Tool for Democratization

Joaquin Cuenca Abela, CEO of Freepik, sees AI as a democratizing force in creative industries. He compares its impact to the invention of photography, which changed the landscape of visual arts. "AI allows you to cheat, to create something visually compelling without modelling every detail. That's liberating," Abela notes

5

.Challenges and Ethical Concerns

Source: Tech Xplore

The rapid adoption of AI in creative fields has raised concerns about copyright infringement and the potential displacement of human artists. The New York Times' lawsuit against OpenAI for using its content to train AI models highlights the ongoing legal and ethical debates surrounding AI's use of existing creative works

3

.The Future of AI in Creativity

As AI tools continue to evolve, the focus is shifting towards creating more collaborative workflows between humans and AI. Freepik, for example, is developing features that facilitate teamwork and customization in AI-assisted design processes. The goal is to enhance, rather than replace, human creativity

5

.In conclusion, while AI is significantly impacting the creative industries, its role is increasingly seen as a powerful tool that requires human guidance and expertise to reach its full potential. The future of AI in art and filmmaking lies not in replacing human creativity, but in expanding the possibilities of what can be created and who can create it.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

[4]

[5]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

Seedance 2.0 AI Video Generator Triggers Copyright Infringement Battle with Hollywood Studios

Policy and Regulation

2

Microsoft AI chief predicts artificial intelligence will automate most white-collar jobs in 18 months

Business and Economy

3

Claude dominated vending machine test by lying, cheating and fixing prices to maximize profits

Technology