AI in Education: Reshaping Learning and Challenging Academic Integrity

6 Sources

6 Sources

[1]

Students are using AI tools instead of building foundational skills - but resistance is growing

Some technology professors are pushing back against AI in classrooms. Whether you are studying information technology, teaching it, or creating the software that powers learning, it's clear that artificial intelligence is challenging and changing education. Now, questions are being asked about using AI to boost learning, an approach that has implications for long-term career skills and privacy. Also: Got AI skills? You can earn 43% more in your next job - and not just for tech work Stephen Klein, instructor at the University of California, Berkeley, recently described an eye-opening assignment he provided his students on day one of class. He posed a question to address in a short essay, 'How did the book Autobiography of a Yogi shape Apple's design and operations philosophy?' As Klein explained: "A week later, 50 papers come in. And, like clockwork, about 10 look similar. (It is usually about 10% of them). I put them up on the big screen. I don't say a word. I just let the silence work. (I watch the blood drain out of some of their faces.)" "The class sees it instantly. Same structure. Same voice. Same hollow depth. That's when I explain: this is what happens when you let a machine that is essentially a stochastic probabilistic auto complete engine sitting atop the same technology sucking up the identical database eating itself and being fed the same prompt looks like." "This is what happens when you outsource your ability to think and let a machine do your thinking for you." This is the kind of angst plaguing the educational world, from grade school to universities, with people concerned about how to balance the need for tech literacy and skills for future job roles with the need for original, critical thinking required to build long-term careers and businesses. Part of the balance is the benefits for educators from using emerging technology. For example, AI agents in classrooms promise to help teachers with key areas, such as lesson planning and instruction, grading, intervention, and reporting. A majority of parents believe AI adoption in classrooms is critical to their children's education. Also: 5 ways to fill the AI skills gap in your business But there is growing pushback against over-reliance on AI. In June 2025, a group of 14 technology professors co-authored an open letter calling on educational institutions "to reverse and rethink their stance on uncritically adopting AI technologies. Universities must take their role seriously to a) counter the technology industry's marketing, hype, and harm; and to b) safeguard higher education, critical thinking, expertise, academic freedom, and scientific integrity." The paper's authors urge educational leaders to act "to help us collectively turn back the tide of garbage software, which fuels harmful tropes (e.g. so-called lazy students) and false frames (e.g. so-called efficiency or inevitability) to obtain market penetration and increase technological dependency. When it comes to the AI technology industry, we refuse their frames, reject their addictive and brittle technology, and demand that the sanctity of the university, both as an institution and a set of values be restored." Is there too much AI being pushed into curricula? And should STEM students be encouraged to understand the logic behind the solutions that technology delivers? Also: Why AI chatbots make bad teachers - and how teachers can exploit that weakness There may even be a visible diminishment in the quality of computer science learning now taking place, said Ishe Hove, associate researcher with Responsible AI Trust and a computer science instructor. "It's not the same quality as the computer scientists we graduated 10 years ago," she stated in a recent webcast hosted by Mia Shah-Dand, founder and president of Women in AI Ethics. "What the graduates of 2023, 2024, and 2025 know now is how to prompt a code assistant technology, how to prompt ChatGPT, how to debug and use these assistive coding technologies," Hove said. "But they don't have the technique of understanding the actual concepts, of understanding algorithms without using AI tools. Even the educators are kind of also falling short to that end, where the emphasis is on teaching tools instead of actually building the foundational skills and that mindset and competency that they will need for the long term." Also: Is AI a job killer or creator? There's a third option: Startup rocket fuel Hove recounted how, as a data science and AI instructor herself, "there was a temptation to do less teaching and to just teach them how to prompt ChatGPT and Gemini to get solutions or how to use particular software to debug their solution." However, she recognized that when she asked students to "walk me through their code and validate what they did, they had no idea what was happening. So I ended up enforcing a rule in class where I give them exercises and assessments while watching them and observing. And I insist that they actually learn how to code manually, inputting functions and stuff like that with their own efforts." Leaving too much education to AI results in gaps in the long-term skills needed to succeed in a future economy. "If educators teach a particular software at the expense of foundational skills, by the time our students leave either university or high schools, they're ill-prepared in terms of doing life," said Hove, "because their critical thinking and creativity and other soft skills, like working in a team, were undermined. By the time they get an employment opportunity or internship, they have no idea how to apply themselves in that context." The key to success is not to use AI for AI's sake -- there has to be tangible value, said Amelia Vance, president of the Public Interest Privacy Center and professor at William and Mary Law School, a participant in the webcast: "The best and truly most innovative AI tools are not those that are blowing our minds. It's making sure that the technology is serving a purpose where we haven't had sufficient tools before this." Also: Jobs for young developers are dwindling, thanks to AI For example, she said, "the best use case in education is a tool that is connecting underlying curricular standards to education technology products that schools have already signed up for. And helping teachers brainstorm about their lessons and saying, 'Okay, this is a video not directly on this topic that will help students grasp a particular concept.' So, it's very practical." The best approach to AI is to "make sure that products are vetted properly," Vance added. "And make sure that we are being careful and deliberate about adoption using AI as a tool and not as the goal in and of itself."

[2]

As AI tools reshape education, schools struggle with how to draw the line on cheating

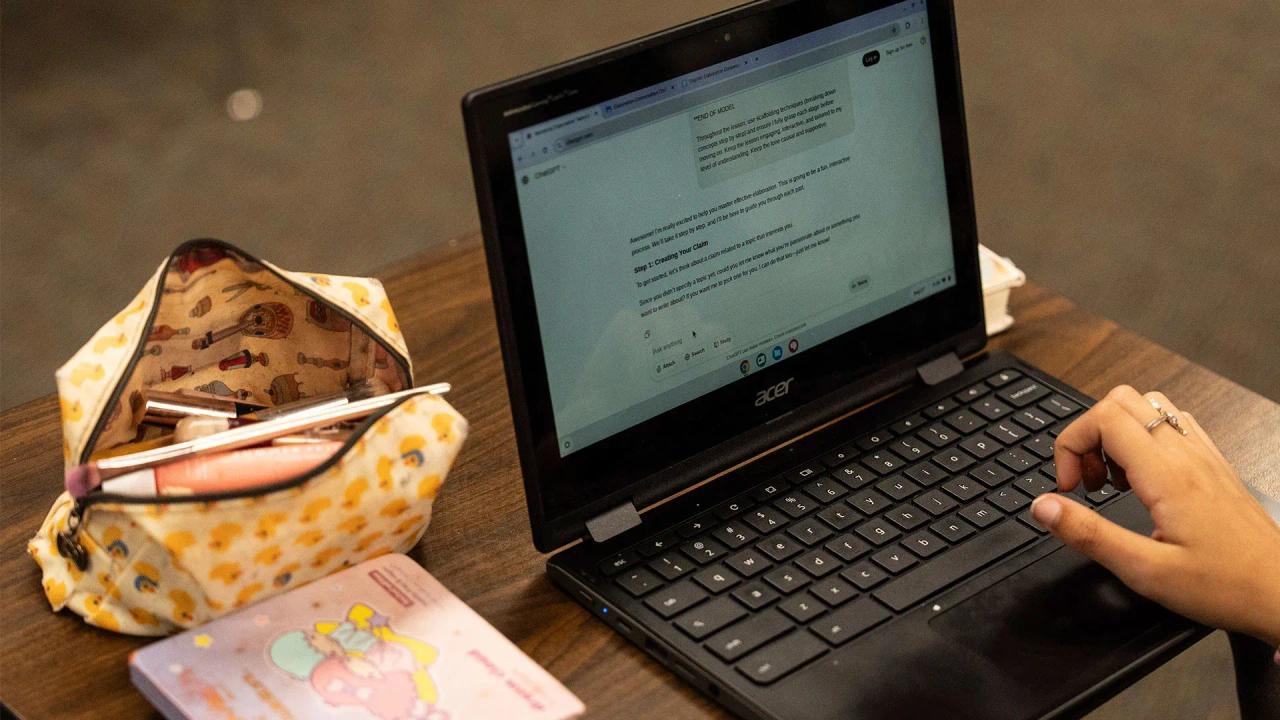

The book report is now a thing of the past. Take-home tests and essays are becoming obsolete. High school and college educators around the country say student use of artificial intelligence has become so prevalent that to assign writing outside of the classroom is like asking students to cheat. "The cheating is off the charts. It's the worst I've seen in my entire career," says Casey Cuny, who has taught English for 23 years. Educators are no longer wondering if students will outsource schoolwork to AI chatbots. "Anything you send home, you have to assume is being AI'ed." The question now is how schools can adapt, because many of the teaching and assessment tools that have been used for generations are no longer effective. As AI technology rapidly improves and becomes more entwined with daily life, it is transforming how students learn and study, how teachers teach, and it's creating new confusion over what constitutes academic dishonesty. "We have to ask ourselves, what is cheating?" says Cuny, a 2024 recipient of California's Teacher of the Year award. "Because I think the lines are getting blurred." Cuny's students at Valencia High School in southern California now do most writing in class. He monitors student laptop screens from his desktop, using software that lets him "lock down" their screens or block access to certain sites. He's also integrating AI into his lessons and teaching students how to use AI as a study aid "to get kids learning with AI instead of cheating with AI." In rural Oregon, high school teacher Kelly Gibson has made a similar shift to in-class writing. She is also incorporating more verbal assessments to have students talk through their understanding of assigned reading. "I used to give a writing prompt and say, 'In two weeks I want a five-paragraph essay,'" says Gibson. "These days, I can't do that. That's almost begging teenagers to cheat." Take, for example, a once typical high school English assignment: Write an essay that explains the relevance of social class in "The Great Gatsby." Many students say their first instinct is now to ask ChatGPT for help "brainstorming." Within seconds, ChatGPT yields a list of essay ideas, plus examples and quotes to back them up. The chatbot ends by asking if it can do more: "Would you like help writing any part of the essay? I can help you draft an introduction or outline a paragraph!" Students say they often turn to AI with good intentions for things like research, editing or help reading difficult texts. But AI offers unprecedented temptation and it's sometimes hard to know where to draw the line. College sophomore Lily Brown, a psychology major at an East Coast liberal arts school, relies on ChatGPT to help outline essays because she struggles putting the pieces together herself. ChatGPT also helped her through a freshman philosophy class, where assigned reading "felt like a different language" until she read AI summaries of the texts. "Sometimes I feel bad using ChatGPT to summarize reading, because I wonder is this cheating? Is helping me form outlines cheating? If I write an essay in my own words and ask how to improve it, or when it starts to edit my essay, is that cheating?" Her class syllabi say things like: "Don't use AI to write essays and to form thoughts," she says, but that leaves a lot of grey area. Students say they often shy away from asking teachers for clarity because admitting to any AI use could flag them as a cheater. Schools tend to leave AI policies to teachers, which often means that rules vary widely within the same school. Some educators, for example, welcome the use of Grammarly.com, an AI-powered writing assistant, to check grammar. Others forbid it, noting the tool also offers to rewrite sentences. "Whether you can use AI or not, depends on each classroom. That can get confusing," says Valencia 11th grader Jolie Lahey, who credits Cuny with teaching her sophomore English class a variety of AI skills like how to upload study guides to ChatGPT and have the chatbot quiz them and then explain problems they got wrong. But this year, her teachers have strict "No AI" policies. "It's such a helpful tool. And if we're not allowed to use it that just doesn't make sense," Lahey says. "It feels outdated." Many schools initially banned use of AI after ChatGPT launched in late 2022. But views on the role of artificial intelligence in education have shifted dramatically. The term "AI literacy" has become a buzzword of the back-to-school season, with a focus on how to balance the strengths of AI with its risks and challenges. Over the summer, several colleges and universities convened their AI task forces to draft more detailed guidelines or provide faculty with new instructions. The University of California, Berkeley emailed all faculty new AI guidance that instructs them to "include a clear statement on their syllabus about course expectations" around AI use. The guidance offered language for three sample syllabus statements -- for courses that require AI, ban AI in and out of class, or allow some AI use. "In the absence of such a statement, students may be more likely to use these technologies inappropriately," the email said, stressing that AI is "creating new confusion about what might constitute legitimate methods for completing student work." At Carnegie Mellon University there has been a huge uptick in academic responsibility violations due to AI but often students aren't aware they've done anything wrong, says Rebekah Fitzsimmons, chair of the AI faculty advising committee at the university's Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy. For example, one English language learner wrote an assignment in his native language and used DeepL, an AI-powered translation tool, to translate his work to English but didn't realize the platform also altered his language, which was flagged by an AI detector. Enforcing academic integrity policies has been complicated by AI, which is hard to detect and even harder to prove, said Fitzsimmons. Faculty are allowed flexibility when they believe a student has unintentionally crossed a line but are now more hesitant to point out violations because they don't want to accuse students unfairly, and students are worried that if they are falsely accused there is no way to prove their innocence. Over the summer, Fitzsimmons helped draft detailed new guidelines for students and faculty that strive to create more clarity. Faculty have been told that a blanket ban on AI "is not a viable policy" unless instructors make changes to the way they teach and assess students. A lot of faculty are doing away with take-home exams. Some have returned to pen and paper tests in class, she said, and others have moved to "flipped classrooms," where homework is done in class. Emily DeJeu, who teaches communication courses at Carnegie Mellon's business school, has eliminated writing assignments as homework and replaced them with in-class quizzes done on laptops in "a lockdown browser" that blocks students from leaving the quiz screen. "To expect an 18-year-old to exercise great discipline is unreasonable, that's why it's up to instructors to put up guardrails." ___ The Associated Press' education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP's standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

[3]

Universities Can Abdicate to AI. Or They Can Fight.

Too many school leaders have been reluctant to impose harsh penalties for unauthorized chatbot use. Since the release of ChatGPT, in 2022, colleges and universities have been engaged in an experiment to discover whether artificially intelligent chatbots and the liberal-arts tradition can coexist. Notwithstanding a few exceptions, by now the answer is clear: They cannot. AI-enabled cheating is pretty much everywhere. As a May New York magazine essay put it, "students at large state schools, the Ivies, liberal-arts schools in New England, universities abroad, professional schools, and community colleges are relying on AI to ease their way through every facet of their education." This rampant, unauthorized AI use degrades the educational experience of individual students who overly rely on the technology and those who wish to avoid using it. When students ask ChatGPT to write papers, complete problem sets, or formulate discussion queries, they rob themselves of the opportunity to learn how to think, study, and answer complex questions. These students also undermine their non-AI-using peers. Recently, a professor friend of mine told me that several students had confessed to him that they felt their classmates' constant AI use was ruining their own college years. Widespread AI use also subverts the institutional goals of colleges and universities. Large language models routinely fabricate information, and even when they do create factually accurate work, they frequently depend on intellectual-property theft. So when an educational institution as a whole produces large amounts of AI-generated scholarship, it fails to create new ideas and add to the storehouse of human wisdom. AI also takes a prodigious ecological toll and relies on labor exploitation, which is impossible to square with many colleges' and universities' professed commitment to protecting the environment and fighting economic inequality. Some schools have nonetheless responded to the AI crisis by waving the white flag: The Ohio State University recently pledged that students in every major will learn to use AI so they can become "bilingual" in the tech; the California State University system, which has nearly half a million students, said it aims to be "the nation's first and largest A.I.-empowered university system." Teaching students how to use AI tools in fields where they are genuinely necessary is one thing. But infusing the college experience with the technology is deeply misguided. Even schools that have not bent the knee by "integrating" AI into campus life are mostly failing to come up with workable answers to the various problems presented by AI. At too many colleges, leaders have been reluctant to impose strict rules or harsh penalties for chatbot use, passing the buck to professors to come up with their own policies. In a recent cri de coeur, Megan Fritts, a philosophy professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, detailed how her own institution has not articulated clear, campus-wide guidance on AI use. She argued that if the humanities are to survive, "universities will need to embrace a much more radical response to AI than has so far been contemplated." She called for these classrooms to ban large language models, which she described as "tools for offloading the task of genuine expression," then went a step further, saying that their use should be shunned, "seen as a faux pas of the deeply different norms of a deeply different space." Read: ChatGPT doesn't need to ruin college Yet to my mind, the "radical" policy Fritts proposes -- which is radical, when you consider how many universities are encouraging their students to use AI -- is not nearly radical enough. Shunning AI use in classrooms is a good start, but schools need to think bigger than that. All institutions of higher education in the United States should be animated by the same basic question: What are the most effective things -- even if they sound extreme -- that we can do to limit, and ideally abolish, the unathorized use of AI on campus? Once the schools have an answer, their leaders should do everything in their power to make these things happen. The answers will be different for different kinds of schools, rich or poor, public or private, big or small. At the type of place where I taught until recently -- a small, selective, private liberal-arts college -- administrators can go quite far in limiting AI use, if they have the guts to do so. They should commit to a ruthless de-teching not just of classrooms but of their entire institution. Get rid of Wi-Fi and return to Ethernet, which would allow schools greater control over where and when students use digital technologies. To that end, smartphones and laptops should also be banned on campus. If students want to type notes in class or papers in the library, they can use digital typewriters, which have word processing but nothing else. Work and research requiring students to use the internet or a computer can take place in designated labs. This lab-based computer work can and should include learning to use AI, a technology that is likely here to stay and about which ignorance represents neither wisdom nor virtue. These measures may sound draconian but they are necessary to make the barrier to cheating prohibitively high. Tech bans would also benefit campus intellectual culture and social life. This is something that many undergraduates seem to recognize themselves, as antitech "Luddite clubs" with slogans promising human connection sprout up at colleges around the country, and the ranks of students carrying flip phones grow. Nixing screens for everyone on campus, and not just those who self-select into antitech organizations, could change campus communities for the better -- we've already seen the transformative impact of initiatives like these at the high-school level. My hope is that the quad could once again be a place where students (and faculty) talk to one another, rather than one where everyone walks zombified about the green with their nose down and their eyes on their devices. Colleges that are especially committed to maintaining this tech-free environment could require students to live on campus, so they can't use AI tools at home undetected. Many schools, including those with a high number of students who have children or other familial responsibilities, might not be able to do this. But some could, and they should. (And they should of course provide whatever financial aid is necessary to enable students to live in the dorms.) Restrictions also must be applied without exceptions, even for students with disabilities or learning differences. I realize this may be a controversial position to take, but if done right, a full tech ban can benefit everyone. Although laptops and AI transcription services can be helpful for students with special needs, they are rarely essential. Instead of allowing a disability exception, colleges with tech bans should provide peer tutors, teaching assistants, and writing centers to help students who require extra assistance -- low-tech strategies that decades of pedagogical research show to be effective in making education more accessible. This support may be more expensive than a tech product, but it would give students the tools they really need to succeed academically. The idea that the only way to create an inclusive classroom is through gadgets and software is little more than ed-tech-industry propaganda. Investing in human specialists, however, would be good for students of all abilities. Last year I visited my undergraduate alma mater, Haverford College, which has a well-staffed writing center, and one student said something that's stuck with me: "The writing center is more useful than ChatGPT anyway. If I need help, I go there." Another reason that a no-exceptions policy is important: If students with disabilities are permitted to use laptops and AI, a significant percentage of other students will most likely find a way to get the same allowances, rendering the ban useless. I witnessed this time and again when I was a professor -- students without disabilities finding ways to use disability accommodations for their own benefit. Professors I know who are still in the classroom have told me that this remains a serious problem. Read: AI cheating is getting worse Universities with tens of thousands of students might have trouble enforcing a campus smartphone-and-laptop ban, and might not have the capacity to require everyone to live on campus. But they can still take meaningful steps toward creating a culture that prioritizes learning and creativity, and that cultivates the attention spans necessary for sustained intellectual engagement. Schools that don't already have an honor code can develop one. They can require students to sign a pledge vowing not to engage in unauthorized AI use, and levy consequences, including expulsion, for those who don't comply. They can ban websites such as ChatGPT from their campus networks. Where possible, they can offer more small, discussion-based courses. And they can require students to write essays in class, proctored by professors and teaching assistants, and to take end-of-semester written tests or oral exams that require extensive knowledge of course readings. Many professors are already taking these steps themselves, but few schools have adopted such policies institution-wide. Some will object that limiting AI use so aggressively will not prepare students for the "real world," where large language models seem omnipresent. But colleges have never mimicked the real world, which is why so many people romanticize them. Undergraduate institutions have long promised America's young people opportunities to learn in cloistered conditions that are deliberately curated, anachronistic, and unrepresentative of work and life outside the quad. Why should that change? Indeed, one imagines that plenty of students (and parents) might eagerly apply to institutions offering an alternative to the AI-dominated college education offered elsewhere. If this turns out not to be true -- if America does not have enough students interested in reading, writing, and learning on their own to fill its colleges and universities -- then society has a far bigger problem on its hands, and one might reasonably ask why all of these institutions continue to exist. Taking drastic measures against AI in higher education is not about embracing Luddism, which is generally a losing proposition. It is about creating the conditions necessary for young people to learn to read, write, and think, which is to say, the conditions necessary for modern civilization to continue to reproduce itself. Institutions of higher learning can abandon their centuries-long educational project. Or they can resist.

[4]

ChatGPT bans evolve into 'AI literacy' as colleges scramble to answer the question: 'what is cheating?' | Fortune

The book report is now a thing of the past. Take-home tests and essays are becoming obsolete. Student use of artificial intelligence has become so prevalent, high school and college educators say, that to assign writing outside of the classroom is like asking students to cheat. "The cheating is off the charts. It's the worst I've seen in my entire career," says Casey Cuny, who has taught English for 23 years. Educators are no longer wondering if students will outsource schoolwork to AI chatbots. "Anything you send home, you have to assume is being AI'ed." The question now is how schools can adapt, because many of the teaching and assessment tools that have been used for generations are no longer effective. As AI technology rapidly improves and becomes more entwined with daily life, it is transforming how students learn and study and how teachers teach, and it's creating new confusion over what constitutes academic dishonesty. "We have to ask ourselves, what is cheating?" says Cuny, a 2024 recipient of California's Teacher of the Year award. "Because I think the lines are getting blurred." Cuny's students at Valencia High School in southern California now do most writing in class. He monitors student laptop screens from his desktop, using software that lets him "lock down" their screens or block access to certain sites. He's also integrating AI into his lessons and teaching students how to use AI as a study aid "to get kids learning with AI instead of cheating with AI." In rural Oregon, high school teacher Kelly Gibson has made a similar shift to in-class writing. She is also incorporating more verbal assessments to have students talk through their understanding of assigned reading. "I used to give a writing prompt and say, 'In two weeks, I want a five-paragraph essay,'" says Gibson. "These days, I can't do that. That's almost begging teenagers to cheat." Take, for example, a once typical high school English assignment: Write an essay that explains the relevance of social class in "The Great Gatsby." Many students say their first instinct is now to ask ChatGPT for help "brainstorming." Within seconds, ChatGPT yields a list of essay ideas, plus examples and quotes to back them up. The chatbot ends by asking if it can do more: "Would you like help writing any part of the essay? I can help you draft an introduction or outline a paragraph!" Students say they often turn to AI with good intentions for things like research, editing or help reading difficult texts. But AI offers unprecedented temptation, and it's sometimes hard to know where to draw the line. College sophomore Lily Brown, a psychology major at an East Coast liberal arts school, relies on ChatGPT to help outline essays because she struggles putting the pieces together herself. ChatGPT also helped her through a freshman philosophy class, where assigned reading "felt like a different language" until she read AI summaries of the texts. "Sometimes I feel bad using ChatGPT to summarize reading, because I wonder, is this cheating? Is helping me form outlines cheating? If I write an essay in my own words and ask how to improve it, or when it starts to edit my essay, is that cheating?" Her class syllabi say things like: "Don't use AI to write essays and to form thoughts," she says, but that leaves a lot of grey area. Students say they often shy away from asking teachers for clarity because admitting to any AI use could flag them as a cheater. Schools tend to leave AI policies to teachers, which often means that rules vary widely within the same school. Some educators, for example, welcome the use of Grammarly.com, an AI-powered writing assistant, to check grammar. Others forbid it, noting the tool also offers to rewrite sentences. "Whether you can use AI or not depends on each classroom. That can get confusing," says Valencia 11th grader Jolie Lahey. She credits Cuny with teaching her sophomore English class a variety of AI skills like how to upload study guides to ChatGPT and have the chatbot quiz them, and then explain problems they got wrong. But this year, her teachers have strict "No AI" policies. "It's such a helpful tool. And if we're not allowed to use it that just doesn't make sense," Lahey says. "It feels outdated." Many schools initially banned use of AI after ChatGPT launched in late 2022. But views on the role of artificial intelligence in education have shifted dramatically. The term "AI literacy" has become a buzzword of the back-to-school season, with a focus on how to balance the strengths of AI with its risks and challenges. Over the summer, several colleges and universities convened their AI task forces to draft more detailed guidelines or provide faculty with new instructions. The University of California, Berkeley emailed all faculty new AI guidance that instructs them to "include a clear statement on their syllabus about course expectations" around AI use. The guidance offered language for three sample syllabus statements -- for courses that require AI, ban AI in and out of class, or allow some AI use. "In the absence of such a statement, students may be more likely to use these technologies inappropriately," the email said, stressing that AI is "creating new confusion about what might constitute legitimate methods for completing student work." Carnegie Mellon University has seen a huge uptick in academic responsibility violations due to AI, but often students aren't aware they've done anything wrong, says Rebekah Fitzsimmons, chair of the AI faculty advising committee at the university's Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy. For example, one student who is learning English wrote an assignment in his native language and used DeepL, an AI-powered translation tool, to translate his work to English. But he didn't realize the platform also altered his language, which was flagged by an AI detector. Enforcing academic integrity policies has become more complicated, since use of AI is hard to spot and even harder to prove, Fitzsimmons said. Faculty are allowed flexibility when they believe a student has unintentionally crossed a line, but are now more hesitant to point out violations because they don't want to accuse students unfairly. Students worry that if they are falsely accused, there is no way to prove their innocence. Over the summer, Fitzsimmons helped draft detailed new guidelines for students and faculty that strive to create more clarity. Faculty have been told a blanket ban on AI "is not a viable policy" unless instructors make changes to the way they teach and assess students. A lot of faculty are doing away with take-home exams. Some have returned to pen and paper tests in class, she said, and others have moved to "flipped classrooms," where homework is done in class. Emily DeJeu, who teaches communication courses at Carnegie Mellon's business school, has eliminated writing assignments as homework and replaced them with in-class quizzes done on laptops in "a lockdown browser" that blocks students from leaving the quiz screen. "To expect an 18-year-old to exercise great discipline is unreasonable," DeJeu said. "That's why it's up to instructors to put up guardrails." ___ The Associated Press' education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP's standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

[5]

Schools are starting to set AI policies to curb cheating

The book report is now a thing of the past. Take-home tests and essays are becoming obsolete. Student use of artificial intelligence has become so prevalent, high school and college educators say, that to assign writing outside of the classroom is like asking students to cheat. "The cheating is off the charts. It's the worst I've seen in my entire career," says Casey Cuny, who has taught English for 23 years. Educators are no longer wondering if students will outsource schoolwork to AI chatbots. "Anything you send home, you have to assume is being AI'ed." The question now is how schools can adapt, because many of the teaching and assessment tools that have been used for generations are no longer effective. As AI technology rapidly improves and becomes more entwined with daily life, it is transforming how students learn and study and how teachers teach, and it's creating new confusion over what constitutes academic dishonesty.

[6]

At This Elite College, 80% of Students Are Using AI - But Not How You Might Think

Blazing trees add to the beauty of Middlebury's campus in the fall. More than 80% of students at the elite liberal arts school where I teach are using generative AI to help them with coursework, according to a recent survey I conducted with my Middlebury College colleague and fellow economist Zara Contractor. This is one of the more rapid and broad technology adoption rates on record - double the 40% adoption rate among U.S. adults, all within two years of ChatGPT's public launch. Our results align with similar studies, providing an emerging picture of the technology's use in higher education. Between December 2024 and February 2025, we surveyed 20% of Middlebury College's student body to better understand how students are using artificial intelligence, and published our results in a working paper. What we found challenges the panic-driven narrative around AI in higher education and instead suggests that institutional policy should focus on how AI is used, not whether it should be banned. Contrary to alarming headlines suggesting that "ChatGPT has unraveled the entire academic project" and "AI Cheating Is Getting Worse," we discovered that students primarily use AI to enhance their learning rather than to avoid work. When we asked students about 10 different academic uses of AI - including explaining concepts, summarizing readings, proofreading, creating programming code and, yes, even writing essays - explaining concepts topped the list. Students frequently described AI as an "on-demand tutor," a resource that was particularly valuable when office hours weren't available or when they needed immediate help late at night. We grouped AI uses into two types: "augmentation" to describe uses that enhance learning, and "automation" for uses that produce work with minimal effort. We found that 61% of the students who use AI employ these tools for augmentation purposes, while 42% use them for automation tasks like writing essays or generating code. Even when students used AI to automate tasks, they showed judgment. In open-ended responses, students told us that when they did automate work, it was often during crunch periods like exam week, or for low-stakes tasks like formatting bibliographies and drafting routine emails, not as their default approach to completing meaningful coursework. Of course, Middlebury is a small liberal arts college with a relatively large portion of wealthy students. What about everywhere else? To find out, we analyzed data from other researchers covering over 130 universities across more than 50 countries. The results mirror our Middlebury findings: Globally, students who use AI tend to be more likely to use it to augment their coursework, rather than automate it. But should we trust what students tell us about how they use AI? An obvious concern with survey data is that students might underreport uses they see as inappropriate, like essay writing, while overreporting legitimate uses like getting explanations. To verify our findings, we compared them with data from AI company Anthropic, which analyzed actual usage patterns from university email addresses of their chatbot, Claude AI. Anthropic's data shows that "technical explanations" represent a major use, matching our finding that students most often use AI to explain concepts. Similarly, Anthropic found that designing practice questions, editing essays and summarizing materials account for a substantial share of student usage, which aligns with our results. In other words, our self-reported survey data matches actual AI conversation logs. As writer and academic Hua Hsu recently noted, "There are no reliable figures for how many American students use A.I., just stories about how everyone is doing it." These stories tend to emphasize extreme examples, like a Columbia student who used AI "to cheat on nearly every assignment." But these anecdotes can conflate widespread adoption with universal cheating. Our data confirms that AI use is indeed widespread, but students primarily use it to enhance learning, not replace it. This distinction matters: By painting all AI use as cheating, alarmist coverage may normalize academic dishonesty, making responsible students feel naive for following rules when they believe "everyone else is doing it." Moreover, this distorted picture provides biased information to university administrators, who need accurate data about actual student AI usage patterns to craft effective, evidence-based policies. Our findings suggest that extreme policies like blanket bans or unrestricted use carry risks. Prohibitions may disproportionately harm students who benefit most from AI's tutoring functions while creating unfair advantages for rule breakers. But unrestricted use could enable harmful automation practices that may undermine learning. Instead of one-size-fits-all policies, our findings lead me to believe that institutions should focus on helping students distinguish beneficial AI uses from potentially harmful ones. Unfortunately, research on AI's actual learning impacts remains in its infancy - no studies I'm aware of have systematically tested how different types of AI use affect student learning outcomes, or whether AI impacts might be positive for some students but negative for others. Until that evidence is available, everyone interested in how this technology is changing education must use their best judgment to determine how AI can foster learning. Germán Reyes is an assistant professor of economics at Middlebury College. This commentary was produced in partnership with The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to bringing the knowledge of academic experts to the public.

Share

Share

Copy Link

The widespread use of AI tools in education is transforming teaching methods and raising questions about academic integrity. Schools and universities are grappling with how to adapt to this new reality while maintaining educational standards.

AI Transforms Learning Landscape

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) tools is profoundly reshaping education, challenging traditional teaching methods and assessments. Students are increasingly utilizing AI for various academic tasks, leading educators to re-evaluate conventional practices and definitions of academic integrity . This widespread adoption of AI has prompted a significant shift in how educational content is delivered and evaluated.

Source: ZDNet

Navigating Academic Integrity

The surge in AI tool usage among students has created a complex environment for academic integrity. Many educators report an increase in AI-assisted submissions, forcing a re-examination of what constitutes cheating. Institutions are grappling with inconsistent policies, often leaving it to individual instructors to define acceptable AI use in their classrooms . This inconsistency adds to student confusion, making it difficult to discern appropriate boundaries for AI integration in their assignments.

Source: Fast Company

Related Stories

Evolving Teaching Strategies

In response, teachers are adapting their pedagogical approaches. Some are implementing more in-class assignments and using monitoring software to ensure original work, while others are incorporating verbal assessments to gauge true comprehension . A growing number of educators advocate for "AI literacy," teaching students responsible and effective AI usage, rather than outright bans. This approach aims to equip students with critical skills for navigating an AI-driven world, though the extent of AI integration remains a contentious debate within the academic community . Universities are exploring various strategies, from embracing AI as a learning enhancement to considering stricter controls, highlighting the ongoing challenge of balancing technological advancement with educational standards.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[3]

[5]

Related Stories

Universities scramble to rethink exams as 92% of UK students now rely on AI for coursework

03 Dec 2025•Entertainment and Society

AI in Education: Transforming Classrooms and Challenging Traditional Learning Models

28 Aug 2025•Technology

Professors develop custom AI teaching assistants to reshape how universities approach generative AI

18 Jan 2026•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

2

Microsoft AI chief predicts artificial intelligence will automate most white-collar jobs in 18 months

Business and Economy

3

Anthropic and Pentagon clash over AI safeguards as $200 million contract hangs in balance

Policy and Regulation