AI models fall for the same optical illusions as humans, revealing how both brains work

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Even AI's mind is blown by this optical illusion

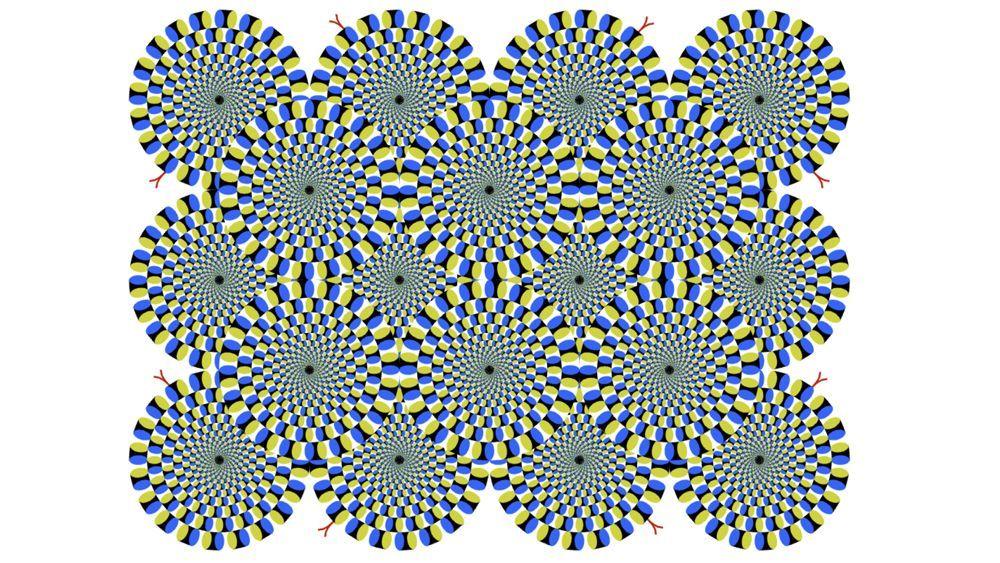

And that could mean the rotating snakes illusion is finally explained. We know from our collection of the best optical illusions that our eyes and brains can play tricks on us. In many cases, scientists still aren't sure why, but the discovery that an AI model can fall for some of the same tricks could help provide an explanation. While some researchers have been training AI models to make optical illusions, others are more concerned about how AI interprets illusions, and whether it can experience them in the same way as humans. And it turns out that the deep neural networks (DNNs) behind many AI algorithms can be susceptible to certain mind benders. Eiji Watanabe is an associate professor of neurophysiology at the National Institute for Basic Biology in Japan. He and his colleagues tested what happens when a DNN is presented with static images that the human brain interprets as being in motion. To do that, they used Akiyoshi Kitaoka's famous rotating snakes illusions. The images show a series of circles, each formed by concentric rings of segments in different colours. The images are still, but viewers tend to think that all the circles are moving other than the specific circle they focus on any one time, which the viewer will usually correctly perceive as static. Watanabe's team used a DNN called PredNet, which was trained to predict future frames in a video based on knowledge acquired from previous ones. It was trained using videos of the kinds of natural landscapes that humans tend to see around them, but not on optical illusions. The model was shown various versions of the rotating snakes illusion as well as an altered version that doesn't trick human brains. The experiment found that the model was fooled by the same images as humans. Watanabe believes the study supports his belief that human brains use something referred to as predictive coding. According to this theory, we don't passively process images of objects in our surroundings. Instead, our visual system first predicts what it expects to see based on past experience. It then processes discrepancies in the new visual input. Based on this theory, the assumption is that there are elements in the rotating snakes images that cause our brain to assume the snakes are moving based on its previous experience. The advantage of this way of processing visual information would presumably be that it allows us to interpret what we see more quickly. The cost is that we sometimes misread a scene as a result. There were some discrepancies between how the AI saw the illusion, though. While humans can 'freeze' any specific circle by starting at it, the AI was unable to do that. The model always sees all of the circles as moving. Watanabe put this down to PredNet's lack of an attention mechanism preventing it from being able to focus on one specific spot. He says that, for now, no deep neural network can experience all optical illusions in the same way that humans do. As tech giants invest billions of dollars trying to create an artificial general intelligence capable of surpassing all human cognitive capabilities, it's perhaps reassuring that - for now - AI has such weaknesses.

[2]

Optical Illusions: Why AI models are succumbing to the same tricks we do

Rotating Snakes illusion shows AI vision mirrors human perception We built them to be cold, calculating, and immune to the subjective flaws of the biological mind. Yet, when shown a specific arrangement of static, colored circles known as the "Rotating Snakes," advanced AI models do something unexpectedly human, they get dizzy. For years, neuroscientists and computer engineers believed that optical illusions were "bugs" in the human operating system - evolutionary shortcuts that left us vulnerable to visual trickery. But as detailed in a fascinating new report by BBC Future, recent research suggests these errors are not biological flaws. They are mathematical inevitabilities of any system, biological or artificial, that tries to predict the future. Also read: Elon Musk says Apple-Google AI deal is bad for all of us, here's why The phenomenon was first flagged when researchers at Japan's National Institute for Basic Biology, led by Eiji Watanabe, trained deep neural networks (DNNs) to predict movement in video sequences. The AI was shown thousands of hours of footage - propellers spinning, cars moving, balls rolling - until it learned the physics of motion. Then, they showed it the Rotating Snakes illusion. To a standard camera, this image is a static grid of pixels. There is zero motion energy. But when the researchers analyzed the AI's internal vectors, they found the system was "hallucinating" rotation. The AI didn't just classify the image; it predicted that the wheels were turning clockwise or counter-clockwise, matching human perception almost perfectly. Why would a supercomputer fall for a parlor trick? The answer lies in a theory called Predictive Coding. The human brain is not a passive receiver of information. If it waited to process every photon hitting the retina, you would be reacting to the world on a massive delay. Instead, the brain is a "prediction machine." It constantly guesses what visual input will come next based on memory and context, only updating its model when there is a significant error. Also read: Sam Altman's problem: Apple's Gemini pick for Siri disempowers ChatGPT The illusion is not a failure of vision. It is the signature of a system optimizing for speed. The AI models that succumb to these illusions are built on this same architecture. They are designed to minimize the "prediction error" (E) between the predicted frame and the actual next frame. When the AI sees the high-contrast shading of the "Rotating Snakes," its learned parameters interpret the pattern as a motion cue. It predicts the next frame should be shifted. When the image remains static, the prediction fires again. The result is a continuous loop of anticipated motion, an artificial hallucination born from the drive to be efficient. The fact that AI succumbs to optical illusions is arguably one of the strongest validations of modern AI architecture. It suggests that as neural networks become more capable of navigating the real world, they are converging on the same solution nature found millions of years ago, predictive processing. We often fear AI hallucinations as a sign of unreliability. But in the realm of vision, these hallucinations are proof that the machine is not just recording data, it is trying to understand it. It is learning to see, and in doing so, it is learning to be tricked.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Researchers discovered that AI models experience optical illusions the same way humans do when shown the rotating snakes illusion. The breakthrough suggests both artificial and biological vision systems rely on predictive coding—a mechanism that anticipates future visual input rather than passively processing images. This finding could finally explain why our brains get tricked by certain patterns.

AI Model Fooled by Optical Illusion in Groundbreaking Study

Eiji Watanabe, an associate professor of neurophysiology at the National Institute for Basic Biology in Japan, led a research team that made a startling discovery about AI's perceptual capabilities

1

. When deep neural networks (DNNs) were shown the rotating snakes illusion—a famous visual trick created by Akiyoshi Kitaoka—the AI hallucinates motion in exactly the same way the human brain does. The illusion consists of static images showing circles formed by concentric rings of colored segments. While completely motionless, viewers perceive all circles as rotating except the specific one they focus on at any given moment.

Source: Digit

The team used PredNet, a DNN trained to predict future frames in videos based on knowledge from previous ones

1

. The model learned from thousands of hours of natural landscape footage—propellers spinning, cars moving, balls rolling—until it understood the physics of motion2

. Crucially, it received no training on optical illusions. When researchers presented various versions of the rotating snakes illusion alongside altered versions that don't trick humans, the AI was fooled by the same images as humans while correctly identifying the non-illusion versions.

Source: Creative Bloq

Predictive Coding in Human Vision Explains the Phenomenon

Watanabe believes this discovery validates the theory of predictive coding, which fundamentally changes how we understand visual processing

1

. Rather than passively receiving information, the human brain functions as a prediction machine that constantly anticipates what visual input will arrive next based on past experience. The system then processes only the discrepancies between predictions and actual new data. If our brains waited to process every photon hitting the retina, we would react to the world with massive delays.According to this theory, specific elements in the rotating snakes images trigger our brain to assume motion based on previous experience. When the AI analyzes the high-contrast shading patterns, its learned parameters interpret these as motion cues, predicting the next frame should be shifted. When the static image remains unchanged, the prediction fires again, creating a continuous loop of anticipated motion. This optimization for speed allows faster interpretation of surroundings, though it occasionally causes misreading of scenes—perceiving motion in a static image.

Key Differences Between Human Perception and AI Vision

Despite the remarkable similarities, important differences emerged in how AI and humans experience these optical illusions. While humans can "freeze" any specific circle by staring directly at it, PredNet always perceives all circles as moving simultaneously

1

. Watanabe attributes this limitation to PredNet's lack of an attention mechanism, which prevents it from focusing on one specific spot the way biological vision systems can.The researcher emphasizes that no deep neural networks can currently experience all optical illusions in the same way humans do

1

. This gap reveals fundamental differences in how artificial and biological systems process visual information, despite their architectural similarities.Related Stories

Why This Matters for AI Development

The fact that AI succumbs to optical illusions represents one of the strongest validations of modern neural network architecture. As these systems become more capable of navigating the real world, they appear to be converging on the same solution nature discovered millions of years ago through evolution. The research suggests that what we often perceive as flaws—prediction error and visual hallucinations—are actually mathematical inevitabilities of any system, biological or artificial, that attempts to predict future states efficiently.

While tech giants invest billions trying to create artificial general intelligence surpassing human cognition, these findings offer perspective on current AI limitations

1

. The discovery that AI models share our perceptual vulnerabilities indicates they are not simply recording data but actively trying to understand it. In the realm of vision, these hallucinations prove the machine is learning to see—and in doing so, learning to be tricked just like us.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

Related Stories

AI Hallucinations on the Rise: New Models Face Increased Inaccuracy Despite Advancements

05 May 2025•Technology

AI Models Struggle with Abstract Visual Reasoning, Falling Short of Human Capabilities

11 Oct 2024•Science and Research

The Limitations of AI Art: A Reflection on Human Creativity and Consciousness

09 Feb 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic sues Pentagon over supply chain risk label after refusing autonomous weapons use

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round as questions swirl around AI bubble and profitability

Business and Economy