Amazon's Alexa Plus Integration with Suno AI Sparks Copyright Concerns in Music Industry

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Amazon is blundering into an AI copyright nightmare

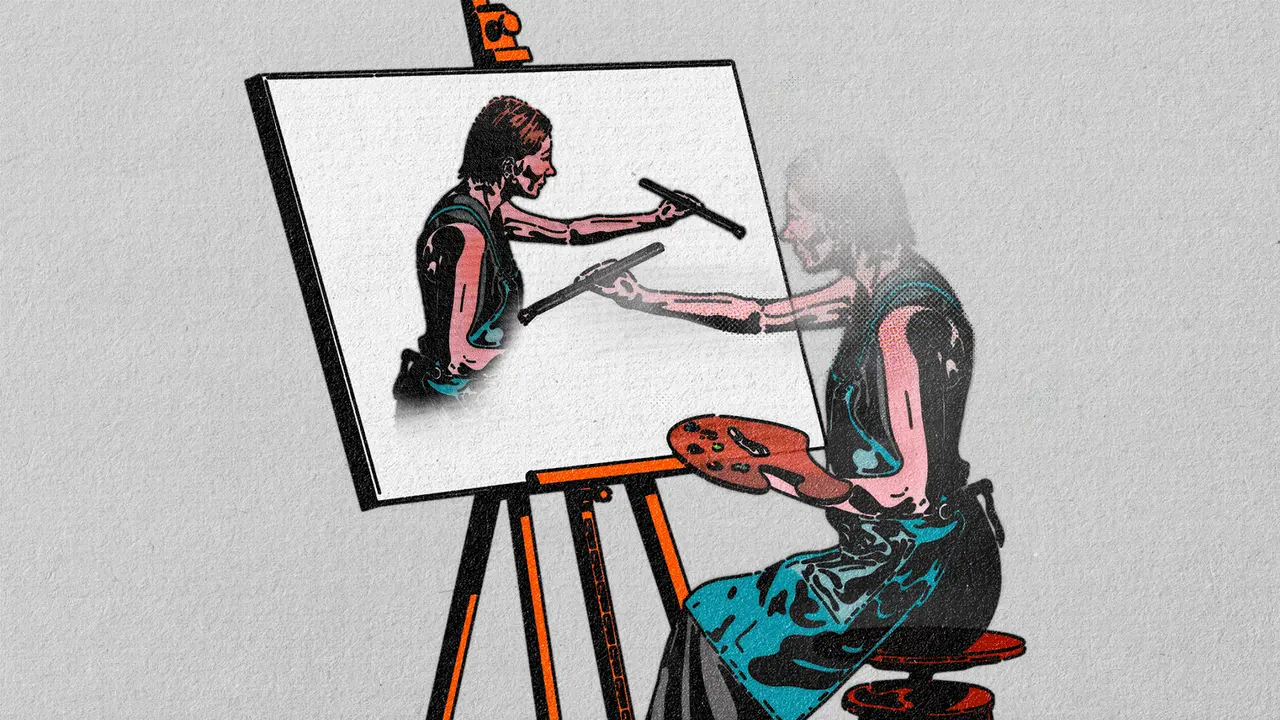

Elizabeth Lopatto is a reporter who writes about tech, money, and human behavior. She joined The Verge in 2014 as science editor. Previously, she was a reporter at Bloomberg. Suno wasn't supposed to be an important part of Amazon's Alexa Plus presentation. The AI song generation platform was a minor demonstration of how Alexa Plus could integrate into other apps, sandwiched between other announcements. But it caught my attention all the same -- because whether Amazon realized it or not, the company blundered into a massive copyright fight. Suno, for those of you not familiar, is an AI song generator: enter a text prompt (such as "a jazz, reggae, EDM pop song about my imagination") and a song comes back. Like many generative AI companies, it is also being sued by all and sundry for ingesting copyrighted material. The parties in the suit -- including major labels and the RIAA -- don't have a smoking gun, since they can't directly peek at Suno's training data. But they have managed to generate some suspiciously similar-sounding AI generated materials, mimicking (among others) "Johnny B. Goode," "Great Balls of Fire," and Jason Derulo's habit of singing his own name. Suno essentially admits these songs were regurgitated from copyrighted source material, but it says such use was legal. "It is no secret that the tens of millions of recordings that Suno's model was trained on presumably included recordings whose rights are owned by the Plaintiffs in this case," it says in its own legal filing. Whether AI training data constitutes fair use is a common but unsettled legal argument, and the plaintiffs contend Suno still amounts to "pervasive illegal copying" of artists' works. Amazon's Suno integration, as demonstrated, requires a Suno account to be linked to Alexa. Suno is meant to be hyper-personalized music, letting anyone generate a song. One of the current core features in Alexa's Echo speakers is taking verbal requests for (non-AI-generated) music. With the Suno demo, Amazon risks antagonizing the very players that make this possible, while simultaneously undercutting Suno's legal case. Amazon declined to provide an on-the-record comment about the Suno demonstration. One of the key questions in a fair use lawsuit -- including the RIAA's suit against Suno -- is whether a derivative work is intended to replace the original thing. In 2023, the Supreme Court found that Andy Warhol had infringed on photographer Lynn Goldsmith's copyright when he screenprinted one of her pictures of Prince; a deciding factor was that outlets like Vanity Fair had licensed Warhol's work instead of Goldsmith's, offering her no credit or payment. This hasn't been tested with AI music, but the RIAA is making similar arguments, and Amazon's integration seems to provide a concrete example. Every minute spent listening to Suno's "All I Want for Christmas Is You" is one spent not listening to Mariah Carey's "All I Want for Christmas is You" through Spotify or Amazon Music Unlimited -- and Carey et al. get stiffed to boot. If "Suno is suddenly available to every Alexa subscriber, that would be of great concern," says Richard James Burgess, the president and CEO of the American Association of Independent Music. (Currently, the feature requires both a Suno subscription and either a subscription for Prime or Alexa Plus.) Burgess emphasized that the problem is the alleged copyright violations, not AI-generated music as a whole. "If it hasn't been licensed correctly from rights holders, then that's problematic for all music," he says. "It affects people's businesses. It affects their livelihoods." Suno, like a lot of other AI companies, offers subscriptions that allow users to generate songs, which are not very good. (The free tier allows 10 songs per day.) I've seen little about how Suno plans to make a sustainable business, but I do know this: if the company is found to have infringed on copyright, the damages for the songs it's already used will be sky-high, on top of any other licensing fees Suno will have to pay. That could result in bankruptcy. I'm not convinced Suno understands why people care about music or what the point is. In a Rolling Stone interview, its cofounder Mikey Shulman complains that musicians are outnumbered by their audience -- it's "so lopsided." I emailed Shulman to see if he wanted to chat for this article. He didn't reply. Music, like all worthwhile art, is about people. If more people want to make music, they can -- by learning how to play an instrument or sing. One of the benefits of learning an instrument is that it deepens your appreciation; suddenly you can hear a song's time signature or notice the difference in feel between keys. You don't even have to be very good to make music people enjoy -- that's why God created punk! The AI songs that have broken through to public consciousness have been ones like "BBL Drizzy" and "10 Drunk Cigarettes," which are not purely AI generated. Rather, there's a musician working with the AI as a tool to curate and edit it. But that's not what the Suno demo showed. Instead, it's just raw prompt generation. This is the least interesting way to interact with generative AI music, and the one that most threatens the actual music industry. An Alexa speaker is not a tool for editing or playing with generative music. There's another way in which Suno can undercut real musicians, besides just stealing listening time. The music industry already has a problem with soundalikes and AI-based fraud; Suno's slop makes it even easier to generate fraudulent tracks. And Amazon is doing itself no favors here, either. Amazon Music has its own deals with record labels, including the ones suing Suno. In a December 2024 press release, Universal Music Group touts an "expanded global relationship" with Amazon that means the "advancement of artist-centric principles." It goes on to say that "UMG and Amazon will also work collaboratively to address, among other things, unlawful AI-generated content, as well as protecting against fraud and misattribution."

[2]

Timbaland's AI Reinvention: 'God Presented This Tool to Me'

Inside Thom Yorke's Amazing New Album with Producer Mark Pritchard Not long ago, Timbaland thought he was tapped out. Since the mid-Nineties, he's repeatedly reinvented R&B, hip-hop, and pop, lacing classics by the likes of Aaliyah, Justin Timberlake, and Jay-Z with skittering beats, future-shock synths, and his outrageous ear for samples and hooks. At age 54, though, the producer worried he was aging out of innovation. "I thought it was over," Timbaland says, sitting in the sun-splashed studio of his Miami mansion. "Music is a young sport. I am the best, right? One of the best producers ever. I can make the drums, but something about it don't hit the same way in this generation." But then Timbaland met Baby Timbo. That's his pet name for Suno, the powerful, controversial AI music generator currently facing a lawsuit from all of the record industry's major labels over its admitted use of countless copyrighted songs in its training data. He is downright evangelical about its capabilities, and recently signed on as a creative consultant for the startup. "You can put out great songs in minutes," he says. "I always wanted to do what Quincy Jones did with Michael Jackson's Thriller when he was [almost] 50. So my Thriller, to me, is this tool. God presented this tool to me. I probably made a thousand beats in three months, and a lot of them -- not all -- are bangers, and from every genre you can possibly think of.... I just did four K-pop songs this morning!" Those thousand beats and songs are just the ones Timbaland considers keepers -- he selected them from more than 50,000 song generations on the app. "It's still my taste," he says. "I don't have to go play it. I can just know what I want to hear." When Suno launched at the end of 2023, it was purely a text-to-music app: You typed a description, wrote some lyrics or had the app create them for you, and a song popped out. While that approach remains, it's since evolved to include more sophisticated options, and Timbaland uses one of them exclusively: a beta feature called "cover songs," which allows you to upload beats or songs of your own creation, and then use Suno to generate infinite variations on them, in every imaginable genre. Timbo gives Baby Timbo tracks from his vast archive of unreleased beats and song ideas, or newer creations, and turns it loose to reinvent them. Timbaland is one of the only big names in music to acknowledge using, let alone advocate, generative AI tools. He's flying in the face of not only a massive lawsuit -- which the industry also brought against a competitor, Udio -- but also major backlash from the artistic community. In April 2024, more than 200 musicians, including Billie Eilish, Nicki Minaj, and Stevie Wonder, signed an open letter denouncing AI music. "Some of the biggest and most powerful companies are using AI to replace human artists, violating our rights, and eroding the value of our work," they wrote, demanding that tech companies "cease the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to infringe upon and devalue the rights of human artists." In February, more than 1,000 U.K. artists -- including Kate Bush, Damon Albarn, and Annie Lennox -- released a soundless "album," Is This What We Want?, to protest proposed laws in their country that would allow AI companies to train on copyrighted material without artists' consent. "The British government must not legalise music theft to benefit AI companies," they collectively declared, while Bush asked, "In the music of the future, will our voices go unheard?" In a sign of just how taboo these tools are, one of the only other prominent producers talking about using them lately is Kanye West, in between rants where he proudly proclaims himself a Nazi. Timbaland is utterly unfazed by his peers' opprobrium, and has no issue with Suno using millions of copyrighted songs to train its AI. "You're talking about copyrights and this or that," he says. "No, man, it's theory. It's learning what is played on Earth.... If it had no knowledge, how can it give you back the answer? So you got to give it knowledge. And that's all it is. Knowledge of musicality." He says musicians should work with AI companies to "figure out, like, how do we eat off of this? And that can be worked out." (Indeed, Suno CEO Mikey Shulman has told Rolling Stone that he expects to eventually work out licensing deals with labels and artists.) Timbaland also has little patience for the idea that AI tools may displace musical jobs for humans -- he's still using subcontracted producers and outside songwriters and lyricists, anyway. "It's going to elevate your job," he says. "It ain't going to just operate on its own. It might give you something that you ain't never thought of, and it becomes the biggest record of your life. Are you gonna criticize it then?... I never want to remove humans from what they do. I just want to inspire them to do more." He compares resistance from artists to early suspicion of Auto-Tuned vocals in the 2000s. "It was a big thing, to the point Jay-Z made 'Death of Auto-Tune,'" he says with a laugh. "Come on now. T-Pain was the only one to step in. Same way I'm doing with this. T-Pain stood out there by himself." Timbaland's current creative partner, Zayd Portillo, a brainy, enthusiastic twentysomething, steps over to the iMac on a desk in the corner, and begins demonstrating their workflow. He plays a song idea Timbaland laid down in 2010 -- a loping, click-clacking beat, a mumbled hook he sang himself with a vaguely East Asian cadence, and a faux-instrumental countermelody that's actually his voice. They uploaded it into Suno, and using the cover-song function, generated variations, using prompts with simple genre descriptions. (Timbaland insists that I don't publish his full actual wording -- they may not be copyrighted, but the prompts are now property he's trying to protect: "They're the sauce!"). In the Suno-generated "covers," AI transforms his hummed countermelody into guitar lines or lovely female voices, fleshing out the song in multiple genres, all with machine-generated vocalists singing vowel-sound non-lyrics that aren't quite in English or any other language. Portillo and an outside songwriter worked out some lyrics to one of those iterations, an R&B banger with buzzy bass. Then they ran the cover-song function again on that version, plugging the new lyrics into the interface -- and they got what they consider to be a finished song, with a sultry female vocalist who happens to not exist. "The writers have all the power," Portillo argues. They're not opposed to the idea of simply releasing the AI version, but they also might send such a song to an artist and have them do their own take on the vocals. Timbaland says he's already trying to get big-name artists to record some of these creations. They demonstrate even wilder approaches. Timbaland took a still-unreleased song he made with Busta Rhymes and used the cover-song function to generate a modern reggae version, with a female voice toasting in a version of Rhymes' flow, still using the rap legend's lyrics. Timbaland sent it to Rhymes and suggested that he rerecord his own verses on this iteration, turning it into a duet with the AI. " I played it for him on FaceTime, and he was freaking out," Timbaland says. So far, the undeniable capabilities of AI music generators have been reflected on the charts only via a counterreaction. Beyoncé said she embraced the organic sound of her Album of the Year-winning Cowboy Carter as a direct response to the technology: "The more I see the world evolving, the more I felt a deeper connection to purity. With artificial intelligence and digital filters and programming, I wanted to go back to real instruments, and I used very old ones." The biggest song of the past few months, Lady Gaga and Bruno Mars' "Die With a Smile," was recorded live in the studio with an actual band. "It's no coincidence that alongside all this live instrumentation is the rise of AI," that song's producer, Andrew Watt, recently told me on an episode of the Rolling Stone Music Now podcast. "People are like, 'OK, computers are getting so good that they can kind of do this other stuff. What's the realest, rawest thing that it can't do?'" But Timbaland has little patience for that sentiment. " If you listen and you feel good, how's it losing humanity?" he asks, raising his voice in frustration. "Why are you beating yourself up on something that's in your body, that you feel?"

Share

Share

Copy Link

Amazon's demonstration of Suno AI integration with Alexa Plus raises copyright issues, while Timbaland embraces AI music generation, highlighting the growing tension between AI technology and the music industry.

Amazon's Alexa Plus Sparks AI Copyright Controversy

Amazon's recent demonstration of Suno AI integration with Alexa Plus has inadvertently thrust the company into a contentious copyright battle within the music industry. The showcase, intended to highlight Alexa Plus's app integration capabilities, has instead raised significant concerns about AI-generated music and its potential impact on copyright laws and artist compensation

1

.Suno AI: A Copyright Nightmare in the Making

Suno, an AI song generation platform, is currently embroiled in a lawsuit filed by major labels and the RIAA. The plaintiffs allege that Suno's AI model, trained on millions of copyrighted recordings, constitutes "pervasive illegal copying" of artists' works. Suno acknowledges using copyrighted material in its training data but argues that such use falls under fair use

1

.Amazon's Risky Move

By integrating Suno into Alexa Plus, Amazon risks antagonizing key players in the music industry while potentially undermining Suno's legal defense. The demonstration showed how users could generate personalized AI songs through Alexa, raising questions about whether such usage could replace traditional music consumption and deprive artists of royalties

1

.Industry Concerns and Legal Implications

Richard James Burgess, CEO of the American Association of Independent Music, expressed concern about the widespread availability of Suno through Alexa, emphasizing the potential impact on artists' livelihoods. The integration could provide concrete examples for the ongoing fair use lawsuit against Suno, potentially strengthening the RIAA's case

1

.Timbaland Embraces AI: A Contrarian View

In stark contrast to the industry's concerns, renowned producer Timbaland has enthusiastically embraced Suno AI as a creative tool. Serving as a creative consultant for the startup, Timbaland views AI as a means to reinvigorate his career and push musical boundaries

2

.Related Stories

The AI Music Debate Intensifies

Timbaland's endorsement of AI music generation stands in opposition to a growing movement within the music community. Over 200 high-profile artists, including Billie Eilish and Stevie Wonder, have signed an open letter denouncing AI music tools as a threat to human artistry and copyright

2

.Future of Music: Collaboration or Conflict?

As the debate rages on, the music industry faces a crucial crossroads. While some, like Timbaland, see AI as a tool for innovation and creativity, others view it as a threat to artistic integrity and fair compensation. The outcome of ongoing legal battles and the industry's ability to adapt to this new technology will likely shape the future of music production and consumption

1

2

.Conclusion

The controversy surrounding Amazon's Suno integration and Timbaland's embrace of AI music generation highlights the complex challenges facing the music industry in the age of artificial intelligence. As technology continues to evolve, finding a balance between innovation and protecting artists' rights remains a critical concern for all stakeholders in the music ecosystem.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[2]

Related Stories

Major Labels Embrace AI Music Platforms After Copyright Battles, Raising Artist Concerns

16 Dec 2025•Entertainment and Society

AI Music Generation: India's Beatoven.ai Leads the Way in Ethical and Creative Approach

22 Jul 2024

AI Music Generation Tools Spark Debate and Disruption in the Music Industry

01 Sept 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic takes Pentagon to court over unprecedented supply chain risk designation

Policy and Regulation

3

Meta smart glasses face lawsuit and UK probe after workers watched intimate user footage

Policy and Regulation