Student Demands Tuition Refund After Catching Professor Using ChatGPT

7 Sources

7 Sources

[1]

Student demands $8,000 refund after catching professor using ChatGPT in class materials

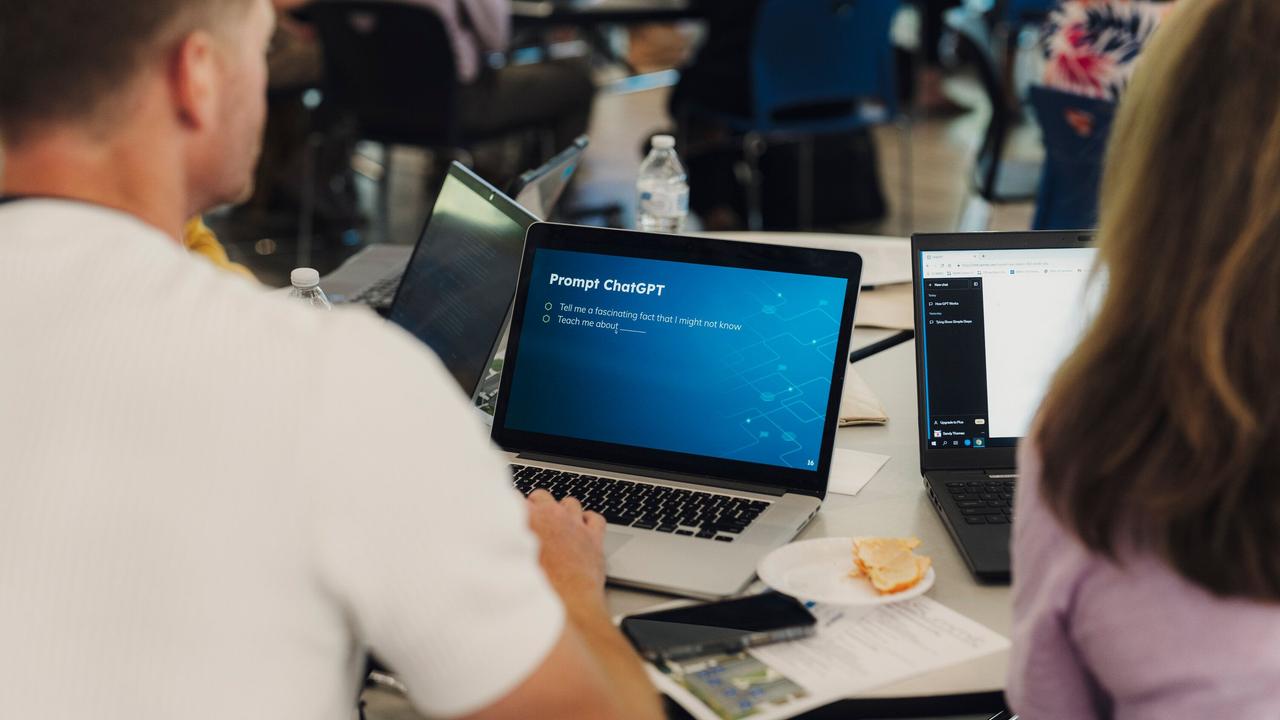

A hot potato: Recent reports suggest that students' use of generative AI to cheat on school assignments is approaching endemic levels. While many worry that tools like ChatGPT erode young people's critical thinking skills, some students have also caught teachers using the same tools, often with unsatisfactory results. The New York Times writes that a Northeastern University student recently filed a formal complaint with the college after discovering that one of her professors used ChatGPT to generate lecture notes and presentation slides. Accusing the professor of hypocrisy for banning students from using the generative AI tool, she demanded the school refund her roughly $8,000 in tuition fees for the course. While a senior at the university, Ella Stapleton noticed that one of her professors accidentally left instructions to ChatGPT within class lecture notes. Midway through the text was a command to "expand on all areas. Be more detailed and specific," followed by a bullet-pointed list. The mistake prompted Stapleton to examine the professor's presentation slides, where she found telltale mistakes typical of GenAI: obvious typos, distorted text, and inaccurate images of body parts. Although she didn't get her money back following graduation, the incident prompted Stapleton's professor to re-examine his materials, realizing that he should've scrutinized ChatGPT's results more closely. Northeastern University still allows generative AI, but the institution's newly adopted policy mandates that users clearly label GenAI output and proofread it for hallucinations. Meanwhile, another student transferred from Southern New Hampshire University last fall after two professors there accidentally left ChatGPT prompts in comments on her essays. She suspected the teachers weren't even reading her work, though one professor denied the accusation. Although these incidents reveal that educators are increasingly using GenAI to grade students, sometimes clumsily, attention has recently turned toward students who use the technology. Reports and teacher complaints suggest that growing numbers of high school and college students use GenAI to cheat on nearly every assignment, and educators can't stop them. New York magazine recently reported that, in some surveys, most students reported using ChatGPT or other AI tools in various ways. Some simply generate outlines or request suggestions for topics to write about, but many copy and paste assignment instructions into chatbot windows and submit the output to teachers. Sometimes, students rewrite or add their own words to AI-generated responses, but professors grading the material often find words such as "As an AI, I am instructed," indicating that students turned it in without reading it. Since OpenAI launched ChatGPT in late 2022, educators have increasingly encountered tell-tale signs of generative AI in students' work: overly smooth grammar, obvious factual inaccuracies, and certain prevalent words. One student in Utah said, "College is just how well I can use ChatGPT at this point." Another student acknowledged that using GenAI can weaken students' critical thinking skills, but admitted they could no longer imagine life without the technology. Meanwhile, a video from a 10th-grade English teacher (above) raising alarms over students' overreliance on AI and other tools recently went viral. In the nearly 10-minute clip, the teacher, who is quitting the profession, explained that some students struggle with reading because they are accustomed to technology reading text aloud to them. Many students use ChatGPT to answer the most basic questions and throw tantrums when asked to use pen and paper. In response, another teacher claimed in the above video to have heard similar complaints from numerous educators. She explained that students in one class used AI to answer a question asking for their personal opinions on a topic, indicating that the technology is replacing their ability to form unique thoughts. Unfortunately, although many professors assume they can detect generative AI output and hallucinations, recent data indicates otherwise. In a study at a UK university last year, professors detected only three percent of AI-generated assignments.

[2]

College Professors Are Using ChatGPT. Some Students Aren't Happy.

Sign up for the On Tech newsletter. Get our best tech reporting from the week. Get it sent to your inbox. In February, Ella Stapleton, then a senior at Northeastern University, was reviewing lecture notes from her organizational behavior class when she noticed something odd. Was that a query to ChatGPT from her professor? Halfway through the document, which her business professor had made for a lesson on models of leadership, was an instruction to ChatGPT to "expand on all areas. Be more detailed and specific." It was followed by a list of positive and negative leadership traits, each with a prosaic definition and a bullet-pointed example. Ms. Stapleton texted a friend in the class. "Did you see the notes he put on Canvas?" she wrote, referring to the university's software platform for hosting course materials. "He made it with ChatGPT." "OMG Stop," the classmate responded. "What the hell?" Ms. Stapleton decided to do some digging. She reviewed her professor's slide presentations and discovered other telltale signs of A.I.: distorted text, photos of office workers with extraneous body parts and egregious misspellings. She was not happy. Given the school's cost and reputation, she expected a top-tier education. This course was required for her business minor; its syllabus forbade "academically dishonest activities," including the unauthorized use of artificial intelligence or chatbots. "He's telling us not to use it, and then he's using it himself," she said. Ms. Stapleton filed a formal complaint with Northeastern's business school, citing the undisclosed use of A.I. as well as other issues she had with his teaching style, and requested reimbursement of tuition for that class. As a quarter of the total bill for the semester, that would be more than $8,000. When ChatGPT was released at the end of 2022, it caused a panic at all levels of education because it made cheating incredibly easy. Students who were asked to write a history paper or literary analysis could have the tool do it in mere seconds. Some schools banned it while others deployed A.I. detection services, despite concerns about their accuracy. But, oh, how the tables have turned. Now students are complaining on sites like Rate My Professors about their instructors' overreliance on A.I. and scrutinizing course materials for words ChatGPT tends to overuse, like "crucial" and "delve." In addition to calling out hypocrisy, they make a financial argument: They are paying, often quite a lot, to be taught by humans, not an algorithm that they, too, could consult for free. For their part, professors said they used A.I. chatbots as a tool to provide a better education. Instructors interviewed by The New York Times said chatbots saved time, helped them with overwhelming workloads and served as automated teaching assistants. Their numbers are growing. In a national survey of more than 1,800 higher-education instructors last year, 18 percent described themselves as frequent users of generative A.I. tools; in a repeat survey this year, that percentage nearly doubled, according to Tyton Partners, the consulting group that conducted the research. The A.I. industry wants to help, and to profit: The start-ups OpenAI and Anthropic recently created enterprise versions of their chatbots designed for universities. (The Times has sued OpenAI for copyright infringement for use of news content without permission.) Generative A.I. is clearly here to stay, but universities are struggling to keep up with the changing norms. Now professors are the ones on the learning curve and, like Ms. Stapleton's teacher, muddling their way through the technology's pitfalls and their students' disdain. Making the Grade Last fall, Marie, 22, wrote a three-page essay for an online anthropology course at Southern New Hampshire University. She looked for her grade on the school's online platform, and was happy to have received an A. But in a section for comments, her professor had accidentally posted a back-and-forth with ChatGPT. It included the grading rubric the professor had asked the chatbot to use and a request for some "really nice feedback" to give Marie. "From my perspective, the professor didn't even read anything that I wrote," said Marie, who asked to use her middle name and requested that her professor's identity not be disclosed. She could understand the temptation to use A.I. Working at the school was a "third job" for many of her instructors, who might have hundreds of students, said Marie, and she did not want to embarrass her teacher. Still, Marie felt wronged and confronted her professor during a Zoom meeting. The professor told Marie that she did read her students' essays but used ChatGPT as a guide, which the school permitted. Robert MacAuslan, vice president of A.I. at Southern New Hampshire, said that the school believed "in the power of A.I. to transform education" and that there were guidelines for both faculty and students to "ensure that this technology enhances, rather than replaces, human creativity and oversight." A dos and don'ts for faculty forbids using tools, such as ChatGPT and Grammarly, "in place of authentic, human-centric feedback." "These tools should never be used to 'do the work' for them," Dr. MacAuslan said. "Rather, they can be looked at as enhancements to their already established processes." After a second professor appeared to use ChatGPT to give her feedback, Marie transferred to another university. Paul Shovlin, an English professor at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, said he could understand her frustration. "Not a big fan of that," Dr. Shovlin said, after being told of Marie's experience. Dr. Shovlin is also an A.I. faculty fellow, whose role includes developing the right ways to incorporate A.I. into teaching and learning. "The value that we add as instructors is the feedback that we're able to give students," he said. "It's the human connections that we forge with students as human beings who are reading their words and who are being impacted by them." Dr. Shovlin is a proponent of incorporating A.I. into teaching, but not simply to make an instructor's life easier. Students need to learn to use the technology responsibly and "develop an ethical compass with A.I.," he said, because they will almost certainly use it in the workplace. Failure to do so properly could have consequences. "If you screw up, you're going to be fired," Dr. Shovlin said. One example he uses in his own classes: In 2023, officials at Vanderbilt University's education school responded to a mass shooting at another university by sending an email to students calling for community cohesion. The message, which described promoting a "culture of care" by "building strong relationships with one another," included a sentence at the end that revealed that ChatGPT had been used to write it. After students criticized the outsourcing of empathy to a machine, the officials involved temporarily stepped down. Not all situations are so clear cut. Dr. Shovlin said it was tricky to come up with rules because reasonable A.I. use may vary depending on the subject. His department, the Center for Teaching, Learning and Assessment, instead has "principles" for A.I. integration, one of which eschews a "one-size-fits-all approach." The Times contacted dozens of professors whose students had mentioned their A.I. use in online reviews. The professors said they had used ChatGPT to create computer science programming assignments and quizzes on required reading, even as students complained that the results didn't always make sense. They used it to organize their feedback to students, or to make it kinder. As experts in their fields, they said, they can recognize when it hallucinates, or gets facts wrong. There was no consensus among them as to what was acceptable. Some acknowledged using ChatGPT to help grade students' work; others decried the practice. Some emphasized the importance of transparency with students when deploying generative A.I., while others said they didn't disclose its use because of students' skepticism about the technology. Most, however, felt that Ms. Stapleton's experience at Northeastern -- in which her professor appeared to use A.I. to generate class notes and slides -- was perfectly fine. That was Dr. Shovlin's view, as long as the professor edited what ChatGPT spat out to reflect his expertise. Dr. Shovlin compared it to a longstanding practice in academia of using content, such as lesson plans and case studies, from third-party publishers. To say a professor is "some kind of monster" for using A.I. to generate slides "is, to me, ridiculous," he said. The Calculator on Steroids Shingirai Christopher Kwaramba, a business professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, described ChatGPT as a partner that saved time. Lesson plans that used to take days to develop now take hours, he said. He uses it, for example, to generate data sets for fictional chain stores, which students use in an exercise to understand various statistical concepts. "I see it as the age of the calculator on steroids," Dr. Kwaramba said. Dr. Kwaramba said he now had more time for student office hours. Other professors, like David Malan at Harvard, said the use of A.I. meant fewer students were coming to office hours for remedial help. Dr. Malan, a computer science professor, has integrated a custom A.I. chatbot into a popular class he teaches on the fundamentals of computer programming. His hundreds of students can turn to it for help with their coding assignments. Dr. Malan has had to tinker with the chatbot to hone its pedagogical approach, so that it offers only guidance and not the full answers. The majority of 500 students surveyed in 2023, the first year it was offered, said they found it helpful. Rather than spend time on "more mundane questions about introductory material" during office hours, he and his teaching assistants prioritize interactions with students at weekly lunches and hackathons -- "more memorable moments and experiences," Dr. Malan said. Katy Pearce, a communication professor at the University of Washington, developed a custom A.I. chatbot by training it on versions of old assignments that she had graded. It can now give students feedback on their writing that mimics her own at any time, day or night. It has been beneficial for students who are otherwise hesitant to ask for help, she said. "Is there going to be a point in the foreseeable future that much of what graduate student teaching assistants do can be done by A.I.?" she said. "Yeah, absolutely." What happens then to the pipeline of future professors who would come from the ranks of teaching assistants? "It will absolutely be an issue," Dr. Pearce said. A Teachable Moment After filing her complaint at Northeastern, Ms. Stapleton had a series of meetings with officials in the business school. In May, the day after her graduation ceremony, the officials told her that she was not getting her tuition money back. Rick Arrowood, her professor, was contrite about the episode. Dr. Arrowood, who is an adjunct professor and has been teaching for nearly two decades, said he had uploaded his class files and documents to ChatGPT, the A.I. search engine Perplexity and an A.I. presentation generator called Gamma to "give them a fresh look." At a glance, he said, the notes and presentations they had generated looked great. "In hindsight, I wish I would have looked at it more closely," he said. He put the materials online for students to review, but emphasized that he did not use them in the classroom, because he prefers classes to be discussion-oriented. He realized the materials were flawed only when school officials questioned him about them. The embarrassing situation made him realize, he said, that professors should approach A.I. with more caution and disclose to students when and how it is used. Northeastern issued a formal A.I. policy only recently; it requires attribution when A.I. systems are used and review of the output for "accuracy and appropriateness." A Northeastern spokeswoman said the school "embraces the use of artificial intelligence to enhance all aspects of its teaching, research and operations." "I'm all about teaching," Dr. Arrowood said. "If my experience can be something people can learn from, then, OK, that's my happy spot."

[3]

Student Livid After Catching Her Professor Using ChatGPT, Asks For Her Money Back

Many students aren't allowed to use artificial intelligence to do their assignments -- and when they catch their teachers doing so, they're often peeved. In an interview with the New York Times, one such student -- Northeastern's Ella Stapleton -- was shocked earlier this year when she began to suspect that her business professor had generated lecture notes with ChatGPT. When combing through those notes, the newly-matriculated student noticed a ChatGPT search citation, obvious misspellings, and images with extraneous limbs and digits -- all hallmarks of AI use. "He's telling us not to use it," Stapleton said, "and then he's using it himself." Alarmed, the senior brought up the professor's AI use with Northeastern's administration and demanded her tuition back. After a series of meetings that ran all the way up until her graduation earlier this month, the school gave its final verdict: that she would not be getting her $8,000 in tuition back. Most of the educators the NYT spoke to -- who, like Stapleton's, had been caught by students using AI tools like ChatGPT -- didn't think it was that big of a deal. To the mind of Paul Shovlin, an English teacher and AI fellow at Ohio University, there is no "one-size-fits-all" approach to using the burgeoning tech in the classroom. Students making their AI-using professors out to be "some kind of monster," as he put it, is "ridiculous." That take, which over-inflates the student's concerns to make her sound hystrionic, dismisses another burgeoning consensus: that others view the use of AI at work as lazy and look down upon people who use it. In a new study from Duke, business researchers found that people both anticipate and experience judgment from their colleagues for using AI at work. The study involved more than 4,400 people who, through a series of four experiments, indicated ample "evidence of a social evaluation penalty for using AI." "Our findings reveal a dilemma for people considering adopting AI tools," the researchers wrote. "Although AI can enhance productivity, its use carries social costs." For Stapleton's professor, Rick Arrowood, the Northeastern lecture notes scandal really drove that point home. Arrowood told the NYT that he used various AI tools -- including ChatGPT, the Perplexity AI search engine, and an AI presentation generator called Gamma -- to give his lectures a "fresh look." Though he claimed to have reviewed the outputs, he didn't catch the telltale AI signs that Stapleton saw. "In hindsight," he told the newspaper, "I wish I would have looked at it more closely." Arrowood said he's now convinced professors should think harder about using AI and disclose to their students when and how it's used -- a new stance indicating that the debacle was, for him, a teachable moment. "If my experience can be something people can learn from," he told the NYT, "then, OK, that's my happy spot."

[4]

The Professors Are Using ChatGPT, and Some Students Aren't Happy About It

In February, Ella Stapleton, then a senior at Northeastern University, was reviewing lecture notes from her organizational behavior class when she noticed something odd. Was that a query to ChatGPT from her professor? Halfway through the document, which her business professor had made for a lesson on models of leadership, was an instruction to ChatGPT to "expand on all areas. Be more detailed and specific." It was followed by a list of positive and negative leadership traits, each with a prosaic definition and a bullet-pointed example. Stapleton texted a friend in the class. "Did you see the notes he put on Canvas?" she wrote, referring to the university's software platform for hosting course materials. "He made it with ChatGPT." "OMG Stop," the classmate responded. "What the hell?" Stapleton decided to do some digging. She reviewed her professor's slide presentations and discovered other telltale signs of artificial intelligence: distorted text, photos of office workers with extraneous body parts and egregious misspellings. She was not happy. Given the school's cost and reputation, she expected a top-tier education. This course was required for her business minor; its syllabus forbade "academically dishonest activities," including the unauthorized use of AI or chatbots. "He's telling us not to use it, and then he's using it himself," she said. Stapleton filed a formal complaint with Northeastern's business school, citing the undisclosed use of AI as well as other issues she had with his teaching style, and requested reimbursement of tuition for that class. As a quarter of the total bill for the semester, that would be more than $8,000. When ChatGPT was released at the end of 2022, it caused a panic at all levels of education because it made cheating incredibly easy. Students who were asked to write a history paper or literary analysis could have the tool do it in mere seconds. Some schools banned it while others deployed AI detection services, despite concerns about their accuracy. But, oh, how the tables have turned. Now students are complaining on sites like Rate My Professors about their instructors' overreliance on AI and scrutinizing course materials for words ChatGPT tends to overuse, such as "crucial" and "delve." In addition to calling out hypocrisy, they make a financial argument: They are paying, often quite a lot, to be taught by humans, not an algorithm that they, too, could consult for free. For their part, professors said they used AI chatbots as a tool to provide a better education. Instructors interviewed by The New York Times said chatbots saved time, helped them with overwhelming workloads and served as automated teaching assistants. Their numbers are growing. In a national survey of more than 1,800 higher-education instructors last year, 18% described themselves as frequent users of generative AI tools; in a repeat survey this year, that percentage nearly doubled, according to Tyton Partners, the consulting group that conducted the research. The AI industry wants to help, and to profit: The startups OpenAI and Anthropic recently created enterprise versions of their chatbots designed for universities. Generative AI is clearly here to stay, but universities are struggling to keep up with the changing norms. Now professors are the ones on the learning curve and, like Stapleton's teacher, muddling their way through the technology's pitfalls and their students' disdain. Making the Grade Last fall, Marie, 22, wrote a three-page essay for an online anthropology course at Southern New Hampshire University. She looked for her grade on the school's online platform, and was happy to have received an A. But in a section for comments, her professor had accidentally posted a back-and-forth with ChatGPT. It included the grading rubric the professor had asked the chatbot to use and a request for some "really nice feedback" to give Marie. "From my perspective, the professor didn't even read anything that I wrote," said Marie, who asked to use her middle name and requested that her professor's identity not be disclosed. She could understand the temptation to use AI. Working at the school was a "third job" for many of her instructors, who might have hundreds of students, said Marie, and she did not want to embarrass her teacher. Still, Marie felt wronged and confronted her professor during a Zoom meeting. The professor told Marie that she did read her students' essays but used ChatGPT as a guide, which the school permitted. Robert MacAuslan, vice president of AI at Southern New Hampshire, said that the school believed "in the power of AI to transform education" and that there were guidelines for both faculty and students to "ensure that this technology enhances, rather than replaces, human creativity and oversight." A do's and don'ts for faculty forbids using tools, such as ChatGPT and Grammarly, "in place of authentic, human-centric feedback." "These tools should never be used to 'do the work' for them," MacAuslan said. "Rather, they can be looked at as enhancements to their already established processes." After a second professor appeared to use ChatGPT to give her feedback, Marie transferred to another university. Paul Shovlin, an English professor at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, said he could understand her frustration. "Not a big fan of that," Shovlin said, after being told of Marie's experience. Shovlin is also an AI faculty fellow, whose role includes developing the right ways to incorporate AI into teaching and learning. "The value that we add as instructors is the feedback that we're able to give students," he said. "It's the human connections that we forge with students as human beings who are reading their words and who are being impacted by them." Shovlin is a proponent of incorporating AI into teaching, but not simply to make an instructor's life easier. Students need to learn to use the technology responsibly and "develop an ethical compass with AI," he said, because they will almost certainly use it in the workplace. Failure to do so properly could have consequences. "If you screw up, you're going to be fired," Shovlin said. One example he uses in his own classes: In 2023, officials at Vanderbilt University's education school responded to a mass shooting at another university by sending an email to students calling for community cohesion. The message, which described promoting a "culture of care" by "building strong relationships with one another," included a sentence at the end that revealed that ChatGPT had been used to write it. After students criticized the outsourcing of empathy to a machine, the officials involved temporarily stepped down. Not all situations are so clear cut. Shovlin said it was tricky to come up with rules because reasonable AI use may vary depending on the subject. The Center for Teaching, Learning and Assessment, where he is a fellow, instead has "principles" for AI integration, one of which eschews a "one-size-fits-all approach." The Times contacted dozens of professors whose students had mentioned their AI use in online reviews. The professors said they had used ChatGPT to create computer science programming assignments and quizzes on required reading, even as students complained that the results didn't always make sense. They used it to organize their feedback to students, or to make it kinder. As experts in their fields, they said, they can recognize when it hallucinates, or gets facts wrong. There was no consensus among them as to what was acceptable. Some acknowledged using ChatGPT to help grade students' work; others decried the practice. Some emphasized the importance of transparency with students when deploying generative AI, while others said they didn't disclose its use because of students' skepticism about the technology. Most, however, felt that Stapleton's experience at Northeastern -- in which her professor appeared to use AI to generate class notes and slides -- was perfectly fine. That was Shovlin's view, as long as the professor edited what ChatGPT spat out to reflect his expertise. Shovlin compared it with a long-standing practice in academia of using content, such as lesson plans and case studies, from third-party publishers. To say a professor is "some kind of monster" for using AI to generate slides "is, to me, ridiculous," he said. The Calculator on Steroids Shingirai Christopher Kwaramba, a business professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, described ChatGPT as a partner that saved time. Lesson plans that used to take days to develop now take hours, he said. He uses it, for example, to generate data sets for fictional chain stores, which students use in an exercise to understand various statistical concepts. "I see it as the age of the calculator on steroids," Kwaramba said. Kwaramba said he now had more time for student office hours. Other professors, including David Malan at Harvard University, said the use of AI meant fewer students were coming to office hours for remedial help. Malan, a computer science professor, has integrated a custom AI chatbot into a popular class he teaches on the fundamentals of computer programming. His hundreds of students can turn to it for help with their coding assignments. Malan has had to tinker with the chatbot to hone its pedagogical approach, so that it offers only guidance and not the full answers. The majority of 500 students surveyed in 2023, the first year it was offered, said they found it helpful. Rather than spend time on "more mundane questions about introductory material" during office hours, he and his teaching assistants prioritize interactions with students at weekly lunches and hackathons -- "more memorable moments and experiences," Malan said. Katy Pearce, a communication professor at the University of Washington, developed a custom AI chatbot by training it on versions of old assignments that she had graded. It can now give students feedback on their writing that mimics her own at any time, day or night. It has been beneficial for students who are otherwise hesitant to ask for help, she said. "Is there going to be a point in the foreseeable future that much of what graduate student teaching assistants do can be done by AI?" she said. "Yeah, absolutely." What happens then to the pipeline of future professors who would come from the ranks of teaching assistants? After filing her complaint at Northeastern, Stapleton had a series of meetings with officials in the business school. In May, the day after her graduation ceremony, the officials told her that she was not getting her tuition money back. Rick Arrowood, her professor, was contrite about the episode. Arrowood, who is an adjunct professor and has been teaching for nearly two decades, said he had uploaded his class files and documents to ChatGPT, the AI search engine Perplexity and an AI presentation generator called Gamma to "give them a fresh look." At a glance, he said, the notes and presentations they had generated looked great. "In hindsight, I wish I would have looked at it more closely," he said. He put the materials online for students to review, but emphasized that he did not use them in the classroom, because he prefers classes to be discussion-oriented. He realized the materials were flawed only when school officials questioned him about them. The embarrassing situation made him realize, he said, that professors should approach AI with more caution and disclose to students when and how it is used. Northeastern issued a formal AI policy only recently; it requires attribution when AI systems are used and review of the output for "accuracy and appropriateness." A Northeastern spokesperson said the school "embraces the use of artificial intelligence to enhance all aspects of its teaching, research and operations." "I'm all about teaching," Arrowood said. "If my experience can be something people can learn from, then, OK, that's my happy spot."

[5]

College Professors Are Turning to ChatGPT to Generate Course Materials. One Student Noticed -- and Asked for a Refund.

Ella Stapleton noticed in February that the lecture notes for her organizational behavior class at Northeastern University appeared to have been generated by ChatGPT. Midway through the document was the statement to "expand on all areas. Be more detailed and specific," which could have been a prompt directed to the AI chatbot. Stapleton looked at other course materials from that class, including slide presentations, and detected AI use in the form of photos of people with extra limbs and misspelled text. She was taken aback, especially because the course syllabus distributed by her professor, Rick Arrowood, prohibited students from using AI. "He's telling us not to use it and then he's using it himself," Stapleton told The New York Times in a report published on Wednesday. Stapleton took the matter up with Northeastern's business school in a formal complaint, asking for her tuition for the class back. The total refund would be over $8,000 for the course. Related: These 4 Words Make It Obvious You Used AI to Write a Paper, According to New Research Northeastern denied Stapleton's request this month, the day after she graduated from the university. Arrowood, an adjunct professor who has been an instructor at various colleges for over fifteen years, admitted to The New York Times that he had put his class files and documents through ChatGPT to refine them. He said that the situation made him approach AI more cautiously and tell students outright when he uses it. Stapleton's situation highlights the growing use of AI in higher education. A survey conducted by consulting group Tyton Partners in 2023 found that 22% of higher-education teachers said they frequently utilized generative AI. The same survey conducted in 2024 found that the percentage had nearly doubled to close to 40% of instructors within the span of a year. AI use is becoming more prevalent among students, too. OpenAI released a study in February showing that more than one-third of young adults in the U.S. ages 18 to 24 use ChatGPT, with 25% of their messages tied to learning and schoolwork. The top two use cases of ChatGPT among this demographic were tutoring and writing help. Related: ChatGPT Is Writing Lots of Job Applications, But Companies Are Quickly Catching On. Here's How. Tyton's 2024 survey found that faculty who use AI are tapping into the technology to create in-class activities, write syllabi, generate rubrics for grading student work, and churn out quizzes and tests. Meanwhile, the study found that students are using AI to help answer homework questions, assist with writing assignments, and take lecture notes. In response to student AI use, colleges have adapted and released guidelines for using ChatGPT and other generative AI. For example, Harvard University advises students to protect confidential data, such as non-public research, when using AI chatbots and ensure that AI-generated content is free from inaccuracies or hallucinations. NYU's policy mandates that students receive instructor approval before using ChatGPT. Universities are also using software to uncover AI use in written materials, like essays. However, New York Magazine reported earlier this month that college students are getting around AI detectors by sprinkling typos into their ChatGPT-written papers. Related: Using ChatGPT? AI Could Damage Your Critical Thinking Skills, According to a Microsoft Study The trend of using AI in college could lead to less critical thinking. Researchers at Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University published a study earlier this year that found that humans who used AI and were confident in its abilities used fewer critical thinking skills. "Used improperly, technologies can and do result in the deterioration of cognitive faculties that ought to be preserved," the researchers wrote.

[6]

Caught red-handed using AI: Student demands tuition fee refund after spotting ChatGPT-generated content in professor's notes

Ella Stapleton expected a premium education at Northeastern University -- one that would justify the hefty ₹6.8 lakh ($8,000) she paid in tuition. What she didn't anticipate was discovering her professor using ChatGPT to craft course content, even as students were discouraged from doing the same. What followed was a formal complaint, a digital paper trail, and a sharp debate about AI in academia. According to The New York Times, the controversy began when Stapleton spotted several glaring red flags in the lecture materials: a suspicious "ChatGPT" citation tucked into the bibliography, numerous typos, and even bizarre AI-generated images where human figures had extra limbs. Her gut feeling screamed something was off. A quick message to a classmate confirmed the suspicion. "Did you see the notes he put on Canvas? He made it with ChatGPT," Stapleton texted. The stunned reply came instantly: "OMG Stop. What the hell?" The professor in question, Rick Arrowood, later admitted to using a trio of AI tools -- ChatGPT, the Perplexity AI search engine, and Gamma, an AI-based presentation maker -- to prepare course materials. While not illegal, this use of AI triggered questions of transparency and academic integrity, particularly when the professor had discouraged students from using similar tools for their own assignments. "He's telling us not to use it, and then he's using it himself," Stapleton pointed out, branding the hypocrisy as unacceptable in a university of Northeastern's standing. The university's AI policy is clear: any faculty member or student using AI-generated content must properly attribute its use, especially when it's part of a scholarly submission. The lack of such attribution, coupled with what Stapleton saw as subpar and automated instruction, led her to demand a full tuition refund. After rounds of meetings, Northeastern University rejected Stapleton's refund request. Professor Arrowood expressed regret, admitting, "In hindsight... I wish I would have looked at it more closely. If my experience can be something people can learn from, then OK, that's my happy spot." Still, the case has opened up a broader conversation: where should the line be drawn when it comes to educators using AI tools in the classroom? ChatGPT, launched in late 2022, rapidly became a household name -- especially among students who embraced it for everything from essays to study guides. Ironically, as universities raced to restrict or regulate student use of AI, educators have been slower to publicly navigate their own ethical boundaries. This incident at Northeastern reflects a new dilemma in the digital age: if AI can empower students and educators alike, can it also redefine the very value of a college education? For Ella Stapleton, the answer was crystal clear -- and cost exactly $8,000.

[7]

A new headache for honest students: proving they didn't use AI

Generative AI tools including ChatGPT are reshaping education for the students who use them to cut corners. According to a Pew Research survey conducted last year, 26% of teenagers said they had used ChatGPT for schoolwork, double the rate of the previous year. Student use of AI chatbots to compose essays and solve coding problems has sent teachers scrambling for solutions.A few weeks into her sophomore year of college, Leigh Burrell got a notification that made her stomach drop. She had received a zero on an assignment worth 15% of her final grade in a required writing course. In a brief note, her professor explained that he believed she had outsourced the composition of her paper -- a mock cover letter -- to an artificial intelligence chatbot. "My heart just freaking stops," said Burrell, 23, a computer science major at the University of Houston-Downtown. But Burrell's submission was not, in fact, the instantaneous output of a chatbot. According to Google Docs editing history that was reviewed by The New York Times, she had drafted and revised the assignment over the course of two days. It was flagged anyway by a service offered by the plagiarism-detection company Turnitin that aims to identify text generated by artificial intelligence. Panicked, Burrell appealed the decision. Her grade was restored after she sent a 15-page PDF of time-stamped screenshots and notes from her writing process to the chair of her English department. Still, the episode made her painfully aware of the hazards of being a student -- even an honest one -- in an academic landscape distorted by AI cheating. Generative AI tools including ChatGPT are reshaping education for the students who use them to cut corners. According to a Pew Research survey conducted last year, 26% of teenagers said they had used ChatGPT for schoolwork, double the rate of the previous year. Student use of AI chatbots to compose essays and solve coding problems has sent teachers scrambling for solutions. But the specter of AI misuse, and the imperfect systems used to root it out, may also be affecting students who are following the rules. In interviews, high school, college and graduate students described persistent anxiety about being accused of using AI on work they had completed themselves -- and facing potentially devastating academic consequences. In response, many students have imposed methods of self-surveillance that they say feel more like self-preservation. Some record their screens for hours at a time as they do their schoolwork. Others make a point of composing class papers using only word processors that track their keystrokes closely enough to produce a detailed edit history. The next time Burrell had to submit an assignment for the class in which she had been accused of using AI, she uploaded a 93-minute YouTube video documenting her writing process. It was annoying, she said, but necessary for her peace of mind. "I was so frustrated and paranoid that my grade was going to suffer because of something I didn't do," she said. These students' fears are borne out by research reported in The Washington Post and Bloomberg Businessweek indicating that AI-detection software, a booming industry in recent years, often misidentifies work as AI-generated. A new study of a dozen AI-detection services by researchers at the University of Maryland found that they had erroneously flagged human-written text as AI-generated about 6.8% of the time, on average. "At least from our analysis, current detectors are not ready to be used in practice in schools to detect AI plagiarism," said Soheil Feizi, an author of the paper and an associate professor of computer science at Maryland. Turnitin, which was not included in the analysis, said in 2023 that its software mistakenly flagged human-written sentences about 4% of the time. A detection program from OpenAI that had a 9% false-positive rate, according to the company, was discontinued after six months. Turnitin did not respond to requests for comment for this article, but has said that its scores should not be used as the sole determinant of AI misuse. "We cannot mitigate the risk of false positives completely given the nature of AI writing and analysis, so, it is important that educators use the AI score to start a meaningful and impactful dialogue with their students in such instances," Annie Chechitelli, Turnitin's chief product officer, wrote in a 2023 blog post. Some students are mobilizing against the use of AI-detection tools, arguing that the risk of penalizing innocent students is too great. More than 1,000 people have signed an online petition started by Kelsey Auman last month, one of the first of its kind, that calls on the University at Buffalo in New York to disable its AI-detection service. A month before her graduation from the university's master of public health program, Auman was told by a professor that three of her assignments had been flagged by Turnitin. She reached out to other members of the 20-person course, and five told her that they had received similar messages, she recalled in a recent interview. Two said that their graduations had been delayed. Auman, 29, was terrified she would not graduate. She had finished her undergraduate studies well before ChatGPT arrived on campuses, and it had never occurred to her to stockpile evidence in case she was accused of cheating using generative AI. "You just assume that if you do your work, you're going to be fine -- until you aren't," she said. Auman said she was concerned that AI-detection software would punish students whose writing fell outside "algorithmic norms" for reasons that had nothing to do with artificial intelligence. In a 2023 study, Stanford University researchers found that AI-detection services were more likely to misclassify the work of students who were not native English speakers. (Turnitin has disputed those findings.) After Auman met with her professor and exchanged lengthy emails with the school's Office of Academic Integrity, she was notified that she would graduate as planned, without any charges of academic dishonesty. "I'm just really glad I'm graduating," she said. "I can't imagine living in this feeling of fear for the rest of my academic career." John Della Contrada, a spokesperson for the University at Buffalo, said that the school was not considering discontinuing its use of Turnitin's AI-detection service in response to the petition. "To ensure fairness, the university does not rely solely on AI-detection software when adjudicating cases of alleged academic dishonesty," he wrote in an email, adding that the university guaranteed due process for accused students, a right to appeal and remediation options for first-time offenders. (Burrell's school, the University of Houston-Downtown, warns faculty members that plagiarism detectors including Turnitin "are inconsistent and can easily be misused," but still makes them available.) Other schools have determined that detection software is more trouble than it is worth: The University of California, Berkeley; Vanderbilt; and Georgetown have all cited reliability concerns in their decisions to disable Turnitin's AI-detection feature. "While we recognize that AI detection may give some instructors peace of mind, we've noticed that overreliance on technology can damage a student-and-instructor relationship more than it can help it," Jenae Cohn, executive director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at UC Berkeley, wrote in an email. Sydney Gill, an 18-year-old high school senior in San Francisco, said she appreciated that teachers were in an extremely difficult position when it came to navigating an academic environment jumbled by AI. She added that she had second-guessed her writing ever since an essay she entered in a writing competition in late 2023 was wrongly marked as AI generated. That anxiety persisted as she wrote college application essays this year. "I don't want to say it's life-changing, but it definitely altered how I approach all of my writing in the future," she said. In 2023, Kathryn Mayo, a professor at Cosumnes River College in Sacramento, California, started using AI-detection tools from Copyleaks and Scribbr on essays from students in her photo-history and photo-theory classes. She was relieved, at first, to find what she hoped would be a straightforward fix in a complex and frustrating moment for teachers. Then she ran some of her own writing through the service, and was notified that it had been partly generated using AI. "I was so embarrassed," she said. She has since changed some of her assignment prompts to make them more personal, which she hopes will make them harder for students to outsource to ChatGPT. She tries to engage any student whom she seriously suspects of misusing AI in a gentle conversation about the writing process. Sometimes students sheepishly admit to cheating, she said. Other times, they just drop the class.

Share

Share

Copy Link

A Northeastern University student filed a complaint and requested an $8,000 tuition refund after discovering her professor used ChatGPT to generate course materials, sparking a debate on AI use in higher education.

Student Uncovers Professor's AI Use in Course Materials

In February 2023, Ella Stapleton, a senior at Northeastern University, made a startling discovery in her organizational behavior class. While reviewing lecture notes, she noticed telltale signs of AI-generated content, including a direct instruction to ChatGPT within the document

1

. Further investigation revealed distorted text, images with extraneous body parts, and egregious misspellings in the professor's slide presentations2

.The Complaint and Refund Request

Stapleton, feeling that the use of AI compromised the quality of her education, filed a formal complaint with Northeastern's business school. She cited the undisclosed use of AI and requested a tuition reimbursement of over $8,000 for the course

3

. The complaint highlighted a perceived hypocrisy, as the course syllabus explicitly forbade students from using AI tools1

.Professor's Response and University Stance

The professor, Rick Arrowood, admitted to using various AI tools, including ChatGPT, Perplexity AI, and Gamma, to give his lectures a "fresh look." He expressed regret for not scrutinizing the AI-generated content more closely

3

. Northeastern University denied Stapleton's refund request, but the incident prompted a broader discussion on AI use in education4

.Growing Trend of AI Use in Higher Education

This incident is not isolated. A survey by Tyton Partners revealed that the percentage of higher-education instructors frequently using generative AI tools nearly doubled from 18% in 2023 to almost 40% in 2024

4

. Professors are increasingly using AI for various tasks, including creating in-class activities, writing syllabi, and generating quizzes5

.Student Reactions and Concerns

Students have expressed mixed feelings about their professors' use of AI. Some, like Stapleton, feel it compromises the quality of education they're paying for. Others have reported instances of professors using ChatGPT for grading and feedback, raising concerns about the authenticity of instructor engagement

2

.Related Stories

Implications for Education Quality

The increasing reliance on AI in education has sparked debates about its impact on critical thinking skills. A study by Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University suggested that improper use of AI technologies could lead to a deterioration of cognitive faculties

5

. This raises questions about the balance between leveraging AI as a tool and maintaining the human element in education.Institutional Responses and Guidelines

Universities are grappling with how to regulate AI use. Some, like Harvard University, have issued guidelines on using ChatGPT and other generative AI tools, emphasizing the protection of confidential data and the need to verify AI-generated content for accuracy

5

. Other institutions, such as NYU, require students to obtain instructor approval before using ChatGPT5

.As AI continues to permeate the educational landscape, institutions, educators, and students are navigating a complex terrain of ethical considerations, quality assurance, and the evolving nature of teaching and learning in the digital age.

References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

2

Microsoft AI chief predicts artificial intelligence will automate most white-collar jobs in 18 months

Business and Economy

3

Anthropic and Pentagon clash over AI safeguards as $200 million contract hangs in balance

Policy and Regulation