AI Breakthrough Enables First 100-Billion-Star Milky Way Simulation

5 Sources

5 Sources

[1]

AI creates the first 100-billion-star Milky Way simulation

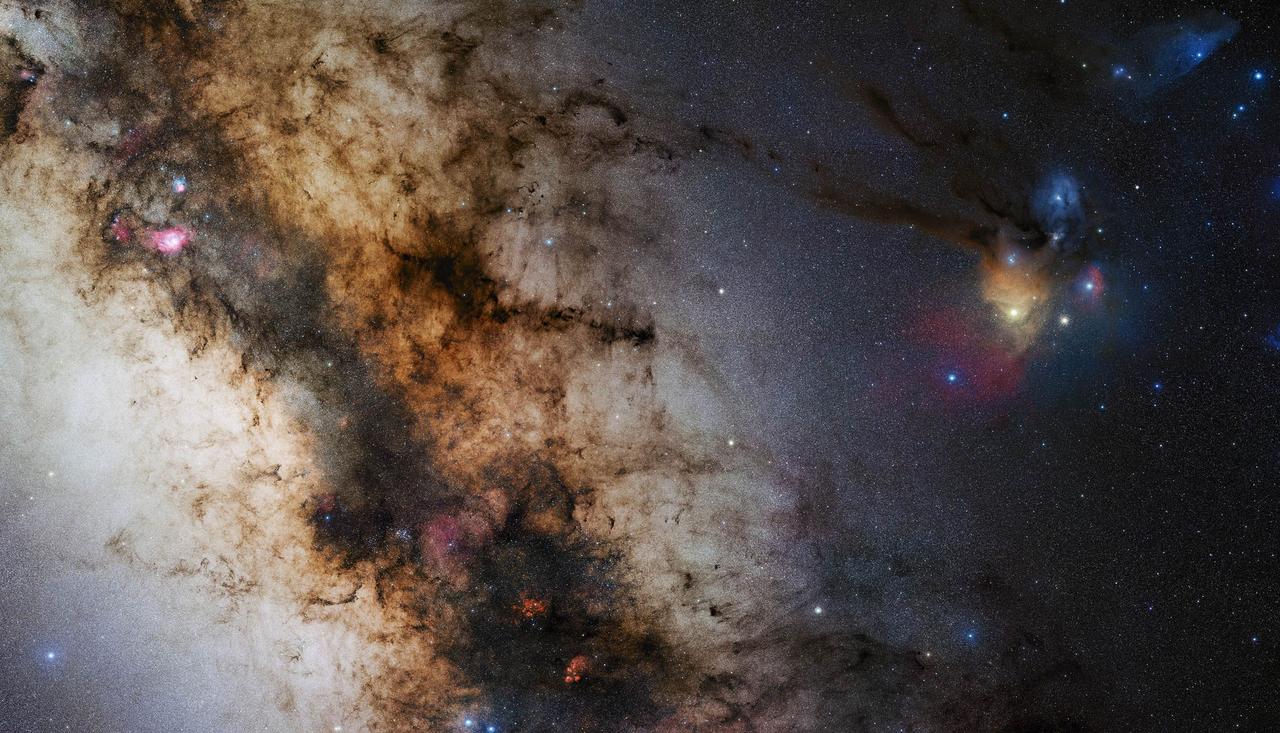

Researchers led by Keiya Hirashima at the RIKEN Center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences (iTHEMS) in Japan, working with partners from The University of Tokyo and Universitat de Barcelona in Spain, have created the first Milky Way simulation capable of tracking more than 100 billion individual stars across 10 thousand years of evolution. The team achieved this milestone by pairing artificial intelligence (AI) with advanced numerical simulation techniques. Their model includes 100 times more stars than the most sophisticated earlier simulations and was generated more than 100 times faster. The work, presented at the international supercomputing conference SC '25, marks a major step forward for astrophysics, high-performance computing, and AI-assisted modeling. The same strategy could also be applied to large-scale Earth system studies, including climate and weather research. Why Modeling Every Star Is So Difficult For many years, astrophysicists have aimed to build Milky Way simulations detailed enough to follow each individual star. Such models would allow researchers to compare theories of galactic evolution, structure, and star formation directly to observational data. However, simulating a galaxy accurately requires calculating gravity, fluid behavior, chemical element formation, and supernova activity across enormous ranges of time and space, which makes the task extremely demanding. Scientists have not previously been able to model a galaxy as large as the Milky Way while maintaining fine detail at the level of single stars. Current cutting-edge simulations can represent systems with the equivalent mass of about one billion suns, far below the more than 100 billion stars that make up the Milky Way. As a result, the smallest "particle" in those models usually represents a group of roughly 100 stars, which averages away the behavior of individual stars and limits the accuracy of small-scale processes. The challenge is tied to the interval between computational steps: to capture rapid events such as supernova evolution, the simulation must advance in very small time increments. Shrinking the timestep means dramatically greater computational effort. Even with today's best physics-based models, simulating the Milky Way star by star would require about 315 hours for every 1 million years of galactic evolution. At that rate, generating 1 billion years of activity would take over 36 years of real time. Simply adding more supercomputer cores is not a practical solution, as energy use becomes excessive and efficiency drops as more cores are added. A New Deep Learning Approach To overcome these barriers, Hirashima and his team designed a method that blends a deep learning surrogate model with standard physical simulations. The surrogate was trained using high-resolution supernova simulations and learned to predict how gas spreads during the 100,000 years following a supernova explosion without requiring additional resources from the main simulation. This AI component allowed the researchers to capture the galaxy's overall behavior while still modeling small-scale events, including the fine details of individual supernovae. The team validated the approach by comparing its results against large-scale runs on RIKEN's Fugaku supercomputer and The University of Tokyo's Miyabi Supercomputer System. The method offers true individual-star resolution for galaxies with more than 100 billion stars, and it does so with remarkable speed. Simulating 1 million years took just 2.78 hours, meaning that 1 billion years could be completed in approximately 115 days instead of 36 years. Broader Potential for Climate, Weather, and Ocean Modeling This hybrid AI approach could reshape many areas of computational science that require linking small-scale physics with large-scale behavior. Fields such as meteorology, oceanography, and climate modeling face similar challenges and could benefit from tools that accelerate complex, multi-scale simulations. "I believe that integrating AI with high-performance computing marks a fundamental shift in how we tackle multi-scale, multi-physics problems across the computational sciences," says Hirashima. "This achievement also shows that AI-accelerated simulations can move beyond pattern recognition to become a genuine tool for scientific discovery -- helping us trace how the elements that formed life itself emerged within our galaxy."

[2]

AI helps build the most detailed Milky Way simulation ever, mapping 100 billion stars

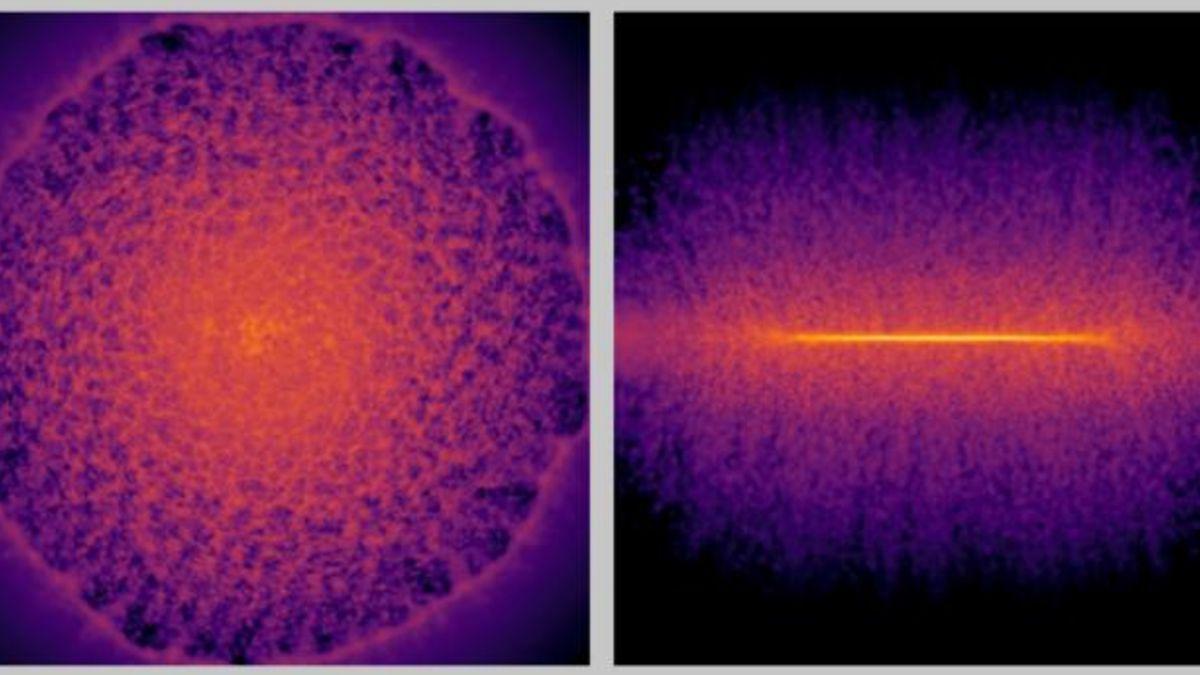

Simulated head-on and side views of the gas distribution after a supernova explosion, as depicted by a deep-learning surrogate model. (Image credit: RIKEN) The most detailed supercomputer simulation ever of our Milky Way galaxy has been created by combining machine learning with numerical models. By running 100 times faster than the next most detailed models, the program gives astronomers the chance to map billions of years of the evolution of our galaxy in months rather than decades. The new simulation contains 100 billion particles representing stars, which is roughly the same number of stars that call the Milky Way home. The previous best-resolution simulations could only manage a billion stars, and were slow. To model a million years of galactic evolution in detail would take 315 hours, or 13 days, in real-time, meaning that to simulate a billion years using those previous best-resolution simulations would take almost 36 years of real computing time. Now, a team led by Keiya Hirashima of the RIKEN Center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences in Japan has developed a new supercomputer-powered simulation that is faster and has far greater star-resolution, thanks to a new methodology that allows both short- and long-time scale events to be included. In comparison, the previous best-resolution simulations only had a billion particles. Each particle would represent 100 stars, but this then smoothed over the details, such as the effect that a single supernova can have on the surrounding gaseous environment. The previous best simulation therefore favored long-term events over short-term phenomena connected to individual stars, but often it is the short-term phenomena that influences the larger scale, longer-term galactic evolution. To process simulations at shorter timescales would require more computing power, but Hirashima's team have been able to side-step this barrier by developing a new methodology. It takes a deep-learning surrogate model -- think of it as a kind of training model -- and applies it to high-resolution supernova data so that it learns to predict how the supernova remnant expands into the interstellar medium over the course of 100,000 years. This expansion blows away gas and dust in the interstellar medium and enriches it with new elements forged by the supernova blast, altering the distribution and chemistry of the interstellar medium. The gas and dust is then eventually converted into the next generation of stars to inhabit the galaxy. By integrating the surrogate model with numerical simulations describing the overall dynamics of the Milky Way, Hirashima's team were able to incorporate the effects of shorter timescale supernova events into the larger timescale galactic processes. The new methodology also sped things up, with a million years of simulation time taking just 2.78 hours to render. At that rate, it would take just 115 days, not 36 years, to simulate a billion years' worth of galactic evolution. "I believe that integrating AI with high-performance computing marks a fundamental shift in how we tackle multi-scale, multi-physics problems across the computational sciences," said Hirashima in a statement. The methodology need not be constrained to astrophysics either; with a little tweaking, it could be used to simulate climate change, oceanic or weather models where small-scale events influence larger scale processes. In the context of galactic evolution, and testing models of how our galaxy formed, how its structure developed and how its chemistry has flourished, the methodology could be transformative. "This achievement also shows that AI-accelerated simulations can move beyond pattern recognition to become a genuine tool for scientific discovery, helping us trace how the elements that formed life itself emerged without our galaxy," said Hirashima. The results of the new simulation were published as part of an international supercomputing conference called SC '25.

[3]

Digital Milky Way project uses AI to track over 100 billion stars in our galaxy

For the first time, scientists have built a digital version of the Milky Way that follows the motion of individual stars, not blurry clumps. The project combines artificial intelligence with leading supercomputers to watch our galaxy change over thousands of years. In plain terms, the team can now model more than one hundred billion stars as separate points in a living map of the galaxy. That level of detail turns the Milky Way from a rough sketch into a detailed movie that researchers can pause and compare with telescopes. The work was led by Keiya Hirashima, an astrophysicist at the RIKEN Center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences. His research uses high performance computing and artificial intelligence to study how galaxies grow, form stars, and recycle the elements that build planets. Astronomers estimate that our galaxy contains roughly one hundred billion stars spread through a thin disk and a surrounding halo. Matching that crowded structure in a computer means tracking every star, every cloud of gas, and the dark matter that pulls them together. To handle this, the team used a N body simulation - a computer model that tracks many particles under gravity. They coupled it to a method that treats gas as moving particles instead of a rigid grid. Galaxies involve events that span from a few light years to a disk about one hundred thousand light years wide. Slow changes such as the rotation of the disk take millions of years, while a supernova can reshape gas quickly. Older galaxy models took a shortcut by bundling many suns into single heavy particles instead of following each star. That saved computing time but blurred out the life cycles of individual stars, especially the massive ones that stir their surroundings when they explode. The new digital Milky Way simulation reaches star by star detail, so the model can tell whether a supernova blasts apart a cloud or leaves it intact. It also follows how heavy elements such as carbon and iron flow into later generations of stars. Achieving that detail would normally force the code to crawl forward in very small time steps, tiny jumps that move every particle briefly. Each explosion would demand many extra steps, so the whole run would spend most of its effort on a few crowded regions. For a Milky Way-sized system, one code would need years of supercomputer time to span a billion years at this level of detail. That barrier, sometimes called the billion particle limit, kept most simulations stuck with either coarse Milky Way models or detailed but much smaller galaxies. To escape this bottleneck, the researchers trained a deep learning model to stand in for the physics of a supernova blast. This model is a kind of artificial intelligence that finds patterns in data and can quickly predict how gas behaves after an explosion. They ran high resolution simulations of single explosions, giving views of gas around each blast down to particles with the mass of our Sun. Those runs trained a surrogate model, a stand in for physics, which learns how cubes of gas hundreds of light years across will evolve. During the digital Milky Way run, the main code steps forward on regular time steps and sends gas near each exploding star to the network. The network predicts how that cube will look one hundred thousand years after the blast and returns the updated gas to the main simulation. Because the main code never shrinks its global time step, the whole simulation runs more efficiently than a traditional approach that resolves every interval. Tests showed that measures such as star formation rates and gas temperatures match results from full physics runs that do not use the surrogate. Making this scheme work still required high performance computing (HPC), large scale computing with many linked processors, on a scale that few facilities can match. Japan's Fugaku supercomputer, built from one hundred sixty thousand nodes based on the A64FX processor, provided most of the number crunching for the project. In technical terms, the team ran a galaxy simulation with about three hundred billion particles on roughly seven million processor cores. That scale breaks the old billion particle barrier that had limited galaxy models to either coarse Milky Way analogs or detailed but smaller systems. Because the surrogate handles the hardest physics, the run can cover one million years of evolution in about two point eight hours. Scaled up to a billion years, that performance would shorten the job from three decades to one hundred fifteen days on the same machines. Compared with a conventional code, this approach delivers a speed up of more than one hundred times for a Milky Way system. The gain comes not from skipping physics but from handling expensive pieces with a trained network instead of brute force updates. This work shows how combined physics based models and machine learning can unlock systems that span ranges in size and time. The same idea of using a trained network to replace the stiffest parts of a simulation is spreading across many areas of science. Scientists have built climate surrogates that mimic parts of weather and climate models, cutting their cost while preserving patterns of rainfall and circulation. These tools make it possible to run many experiments that explore different greenhouse futures or test how sensitive a region is to warming. Hydrologists have built modeling frameworks that use surrogates to stand in for water cycle models, allowing studies of river basins, reservoirs, and flood risk. A broader review of artificial intelligence in climate science points to benefits for tracking extremes such as heat waves, droughts, and wildfires. The digital Milky Way project shows how this strategy lets scientists trace gas and stars and link them to what telescopes see today. "Integrating AI with high-performance computing marks a fundamental shift," said Hirashima. The study is published in the Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis. -- - Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

[4]

Scientists use AI to build the most detailed Milky Way model ever made

Scientists have created the first-ever simulation that models every one of the Milky Way's 100 billion stars, using AI to run galaxy-scale physics 100 times faster than previous methods. A new breakthrough AI-assisted simulation of the Milky Way is giving scientists their most detailed look yet at how our galaxy evolves. Tracking more than 100 billion individual stars across 10,000 years of evolution, the model offers a remarkable level of resolution that astrophysicists have been chasing for decades. Until now, the most advanced simulations bundled stars into large groups, smoothing out the small-scale physics that shape how galaxies grow and change. The new method changes that entirely. By blending deep learning with traditional physics-based modelling, the team was able to generate a galaxy-scale simulation 100 times faster than previous techniques, while using 100 times more stars. To understand how the Milky Way formed and continues to evolve, scientists need models that capture everything from the galaxy's vast spiral structure down to the behaviour of individual stars and supernovae. But the physics involved - gravity, gas dynamics, chemical enrichment and explosive stellar deaths - unfold across wildly different timescales. Capturing fast events like supernova explosions requires the simulation to step forward in tiny increments, a process so computationally demanding that modelling a billion years of galactic history could take decades. The project, a collaboration led by the researcher Keiya Hirashima at the RIKEN Center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences (iTHEMS) in Japan, alongside colleagues from the University of Tokyo and the University of Barcelona. It was recently presented at SC'25 (International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage, and Analysis). Hirashima's team solved this issue by introducing a deep learning surrogate model. Trained on high-resolution simulations of supernova behaviour, the AI learned to predict how gas disperses in the 100,000 years following an explosion. The main simulation could then advance much more quickly, while preserving the detail of individual supernova events. The approach was validated using data from Japan's Fugaku supercomputer and the University of Tokyo's Miyabi system. The result is a full-scale Milky Way simulation that achieves true individual-star resolution and runs far more efficiently. One million years of galactic evolution now takes just 2.78 hours, meaning a billion years could be simulated in around 115 days instead of 36 years. While the achievement is a milestone for astrophysics, its implications stretch well beyond space science. "Similar methods to ours could be applied to simulations of cosmic large-scale structure formation, black hole accretion, as well as simulations of weather, climate, and turbulence," the paper states. Hybrid AI-physics methods like this could dramatically accelerate those models, potentially making them both faster and more accurate. "I believe that integrating AI with high-performance computing marks a fundamental shift in how we tackle multi-scale, multi-physics problems across the computational sciences," Hirashima said. "This achievement also shows that AI-accelerated simulations can move beyond pattern recognition to become a genuine tool for scientific discovery - helping us trace how the elements that formed life itself emerged within our galaxy," he added. The next step for the team will be scaling the technique further and exploring its applications to Earth system modelling.

[5]

Japan researchers simulate Milky Way with 100 billion stars using AI

The model uses an AI surrogate trained on high resolution supernova data to replace millions of tiny physics steps. Researchers in Japan have developed the first simulation of the Milky Way galaxy that tracks more than 100 billion individual stars by combining artificial intelligence with supercomputing capabilities. Presented at the SC '25 supercomputing conference in St. Louis, the model simulates 10,000 years of galactic evolution and operates 100 times faster than prior techniques to address computational limitations in modeling large-scale cosmic structures. Prior simulations reached the state of the art by managing galaxies with stellar masses equivalent to about one billion suns, which represents only one-hundredth of the Milky Way's actual stellar population. These efforts relied on conventional physics-based methods that demand extensive processing power. For instance, such approaches require 315 hours to compute one million years of galactic evolution. Extending this to a billion-year timeframe would necessitate more than 36 years of continuous computation, rendering full-scale Milky Way simulations impractical for most research timelines. The advancement stems from a deep learning surrogate model trained using high-resolution simulations of supernova events. This artificial intelligence element acquires the ability to forecast the expansion of gas over the 100,000 years after a supernova detonation. By doing so, it eliminates the need for numerous small, resource-intensive timesteps in the overall simulation process while preserving the precision of physical outcomes. The research team deployed this system across 7 million CPU cores, utilizing RIKEN's Fugaku supercomputer alongside the University of Tokyo's Miyabi system, to achieve these efficiencies. With this setup, the simulation time dropped to 2.78 hours for each million years of evolution, allowing a projection spanning one billion years to complete in roughly 115 days. Hirashima stated, "Integrating AI with high-performance computing marks a fundamental shift in how we tackle multi-scale, multi-physics problems across the computational sciences." He highlighted potential uses in climate modeling, weather prediction, and oceanography, where challenges arise from connecting small-scale phenomena to broader system dynamics. The resulting simulation permits scientists to follow the emergence of elements vital for life throughout the galaxy's history. This capability provides insights into the chemical evolution processes that contributed to the formation of planets resembling Earth.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Japanese researchers have created the most detailed Milky Way simulation ever, tracking 100 billion individual stars using AI-accelerated computing. The breakthrough runs 100 times faster than previous methods and could revolutionize climate and weather modeling.

Revolutionary AI-Powered Galactic Simulation

Researchers led by Keiya Hirashima at the RIKEN Center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences (iTHEMS) in Japan have achieved a groundbreaking milestone in astrophysics by creating the first Milky Way simulation capable of tracking more than 100 billion individual stars

1

. Working with partners from The University of Tokyo and Universitat de Barcelona, the team presented their work at the international supercomputing conference SC '25, marking a significant advancement in computational astrophysics4

.

Source: Euronews

The simulation represents a dramatic leap forward, incorporating 100 times more stars than the most sophisticated previous models while generating results more than 100 times faster

1

. This achievement addresses a long-standing challenge in astrophysics where scientists have struggled to create detailed galactic models that can follow individual stellar behavior across the vast scales of space and time.Overcoming Computational Barriers

Previous state-of-the-art simulations could only manage systems with stellar masses equivalent to about one billion suns, representing merely one-hundredth of the Milky Way's actual stellar population

5

. These earlier models bundled roughly 100 stars into single particles, which averaged away individual stellar behavior and limited the accuracy of small-scale processes2

.The computational challenge stemmed from the need to capture rapid events like supernova explosions, which required simulations to advance in extremely small time increments. Using traditional physics-based methods, simulating the Milky Way star by star would require approximately 315 hours for every 1 million years of galactic evolution

1

. At this rate, generating 1 billion years of galactic activity would take over 36 years of real computing time, making such detailed simulations practically impossible.Deep Learning Breakthrough

Hirashima's team overcame these barriers by developing a hybrid approach that combines a deep learning surrogate model with standard physical simulations

3

. The AI component was trained using high-resolution supernova simulations and learned to predict how gas spreads during the 100,000 years following a supernova explosion without requiring additional computational resources from the main simulation.

Source: Space

This surrogate model acts as a sophisticated stand-in for complex physics calculations, handling the most computationally expensive aspects of the simulation through trained neural networks rather than brute-force numerical methods

3

. During the main simulation, the code sends gas data near each exploding star to the AI network, which predicts the gas distribution 100,000 years after the blast and returns the updated information to the primary simulation.Related Stories

Unprecedented Performance and Scale

The results demonstrate remarkable efficiency improvements. The new method can simulate 1 million years of galactic evolution in just 2.78 hours, meaning that 1 billion years of evolution could be completed in approximately 115 days instead of the previous 36-year requirement

2

.The team validated their approach by comparing results against large-scale runs on RIKEN's Fugaku supercomputer and The University of Tokyo's Miyabi Supercomputer System

1

.The simulation operates at an unprecedented scale, running galaxy simulations with approximately 300 billion particles across roughly 7 million processor cores

3

. This breakthrough shatters the previous "billion particle limit" that had constrained galaxy models to either coarse Milky Way analogs or detailed but much smaller galactic systems.

Source: Earth.com

Broader Scientific Applications

The implications of this hybrid AI-physics methodology extend far beyond astrophysics. Hirashima emphasized that similar approaches could revolutionize computational science fields facing comparable multi-scale challenges, including meteorology, oceanography, and climate modeling

4

. These fields often struggle with linking small-scale physical phenomena to large-scale system behavior, precisely the problem this new approach addresses."I believe that integrating AI with high-performance computing marks a fundamental shift in how we tackle multi-scale, multi-physics problems across the computational sciences," Hirashima stated

1

. The methodology demonstrates that AI-accelerated simulations can move beyond pattern recognition to become genuine tools for scientific discovery, helping researchers trace how elements essential for life emerged within our galaxy.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

Related Stories

AI Revolutionizes Solar Data Analysis: Bridging Past and Present Observations

17 Apr 2025•Science and Research

AI discovers 800 cosmic anomalies in Hubble Space Telescope archives, some defy classification

27 Jan 2026•Science and Research

Google DeepMind's AI Revolutionizes Gravitational Wave Detection at LIGO

05 Sept 2025•Science and Research

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic sues Pentagon over supply chain risk label after refusing autonomous weapons use

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round as questions swirl around AI bubble and profitability

Business and Economy