Major Labels Embrace AI Music Platforms After Copyright Battles, Raising Artist Concerns

3 Sources

3 Sources

[1]

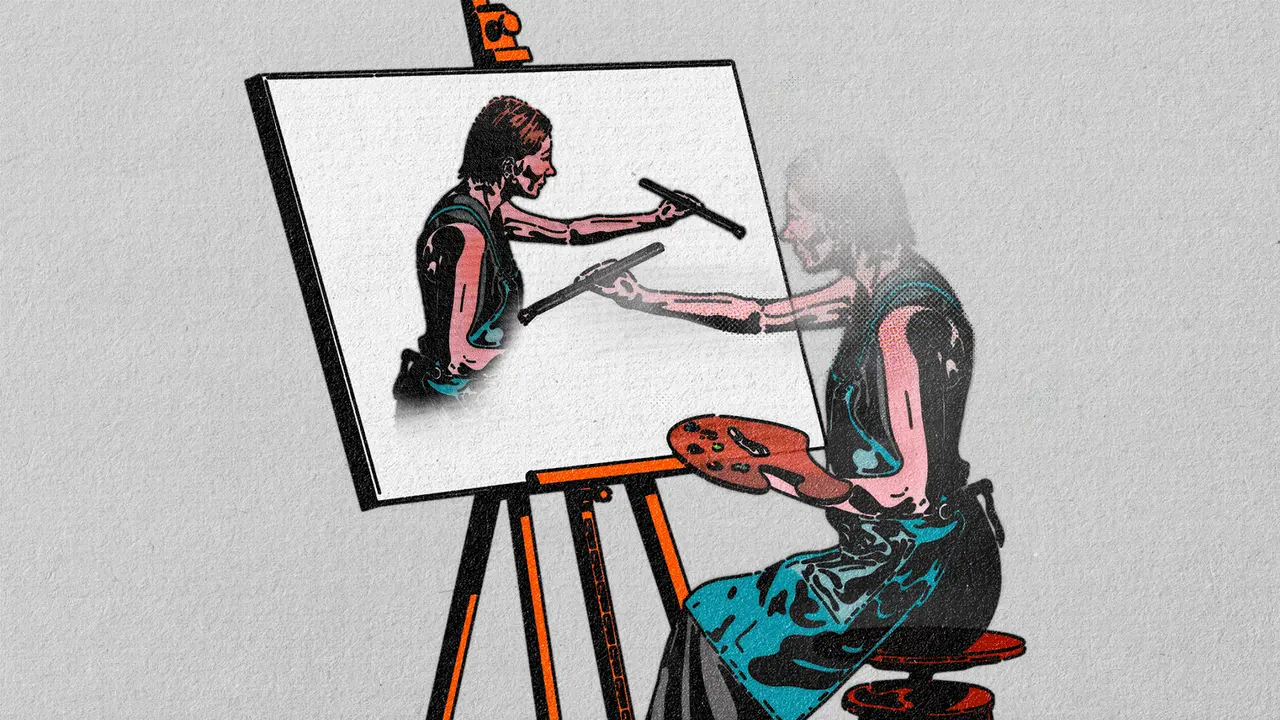

AI Is Testing What Society Wants From Music

The emerging technology is warping the record industry in all sorts of strange -- and foreboding -- ways. Human beings may have sang before they spoke. Scientists from Charles Darwin onward have speculated that, for our early ancestors, music predated -- and possibly formed the basis of -- language. The "singing Neanderthals" theory is a reminder that humming and drumming are fundamental aspects of being human. Even babies have some musical instinct, as anyone who's watched a toddler try to bang their tray to a beat knows. This ought to be kept in mind when evaluating the rhetoric surrounding the topic of music made by artificial intelligence. This year, the technology created songs that amassed millions of listens and inspired major-label deals. The pro and anti sides have generally coalesced around two different arguments: one saying AI will leech humanity out of music (which is bad), and the other saying it will further democratize the art form (which is good). The truth is that AI is already doing something stranger. It's opening a Pandora's box that will test what we, as a society, really want from music. The case against AI music feels, to many, intuitive. The model for the most popular platform, Suno, is trained on a huge body of historical recordings, from which it synthesizes plausible renditions of any genre or style the user asks for. This makes it, debatably, a plagiarism machine (though, as the company argued in its response to copyright-infringement lawsuits from major labels last year, "The outputs generated by Suno are new sounds"). The technology also seems to devalue the hard work, skill, and knowledge that flesh-and-blood musicians take pride in -- and threaten the livelihoods of those musicians. Another problem: AI music tends to be, and I don't know how else to put this, creepy. When I hear a voice from nowhere reciting auto-generated lyrics about love, sadness, and partying all night, I often can't help but feel that life itself is being mocked. Aversion to AI music is so widespread that corporate interests are now selling themselves as part of the resistance. iHeartRadio, the conglomerate that owns most of the commercial radio stations in the country as well as a popular podcast network, recently rolled out a new tagline: "Guaranteed Human." Tom Poleman, its president, decreed that the company won't employ AI personalities or play songs that have purely synthetic lead vocals. Principles may underlie this decision, but so does marketing. Announcing the policy, Poleman cited research showing that although 70 percent of consumers "say they use AI as a tool," 90 percent "want their media to be from real humans." The AI companies have been refining a counterargument: Their technology actually empowers humanity. In November, a Suno employee named Rosie Nguyen posted on X that when she was a little girl, in 2006, she aspired to be a singer, but her parents were too poor to pay for instruments, lessons, or studio time. "A dream I had became just a memory, until now," she wrote. Suno, which can turn a lyric or hummed melody into a fully written song in an instant, was "enabling music creation for everyone," including kids like her. Paired with a screenshot of an article about the company raising $250 million in funding and being valued at $2.5 billion, Nguyen's story triggered outrage. Critics pointed out that she was young exactly at the time when free production software and distribution platforms enabled amateurs to make and distribute music in new ways. A generation of bedroom artists turned stars has shown that people with talent and determination will find a way to pursue their passions, whether or not their parents pay for music lessons. The eventual No. 1 hitmaker Steve Lacy recorded some early songs on his iPhone; Justin Bieber built an audience on YouTube. But Nguyen wasn't totally wrong. AI does make the creation of professional-sounding recordings more accessible -- including to people with no demonstrated musical skills. Take Xania Monet, an AI "singer" whose creator was reportedly offered a $3 million record contract after its songs found streaming success. Monet is the alias of Telisha "Nikki" Jones, a 31-year-old Mississippi entrepreneur who used Suno to convert autobiographical poetry into R&B. The creator of Bleeding Verse, an AI "band" that has drawn ire for outstreaming established emo-metal acts, told Consequence that he's a former concrete-company supervisor who came across Suno through a Facebook ad. Read: The people outsourcing their thinking to AI These examples raise all sorts of questions about what it really means to create music. If a human types a keyword that generates a song, how much credit should the human get? What if the human plays a guitar riff, asks the software to turn that riff into a song, and then keeps using Suno to tweak and retweak the output? Nguyen replied to her critics by saying that the "misconception here is that 'there's no effort put in by a human,' when so many musicians I know using Suno are pouring hours and hours into music production and creation." In practice, however, AI is helping even established musicians work less, or at least to work faster. The Verge reported this month that the technology has become ubiquitous in the country-music world, where Nashville pros are using it to flesh out demos and write melodies. The producer Jacob Durrett said in that story that Suno affords him "a productivity boost more than a creative boost"; the publisher Eric Olson said that it allows him to spend more time with his kids. Similar practices are happening in other genres. The Recording Academy's CEO, Harvey Mason Jr., recently said many of the producers and songwriters he knows are using AI in some capacity. While the technology quietly reshapes the industry, the first-order effect of AI's ease of use is simply the existence of more music -- a lot more. Suno users generate 7 million new tracks a day, which every two weeks nets out to about as many songs as exist on Spotify. Most of those tracks are likely never heard by anyone. Still, the streaming service Deezer has disclosed that nearly a third of the music uploaded daily to its platform is AI-generated. Spotify has said that it will crack down on obvious slop and spam -- but definitively detecting when AI has been used to make a song is hard, and only going to get harder. I admit to feeling some sadistic curiosity about what a full fire hose of AI music, intersecting with streaming algorithms tuned to deliver to users exactly what they want to hear, might reveal about listening desires. Historically, popular art tends to progress by the logic of MAYA: "Most Advanced Yet Acceptable." Hit songs are usually neither wholly original nor wholly derivative but rather some delectable combination of the two. At a glance, AI may seem incapable of newness because it's trained to replicate music's past; many of the breakout AI songs to date sound incredibly familiar. But other examples show that the technology can, perhaps accidentally, carve new pathways. Those are not always good pathways -- but they are ear-teasingly novel, the results of choices a person probably wouldn't or couldn't make on their own (again: creepy). In Bleeding Verse's viral track "Only When It's You," the vocals have a scuzzy vibrato, almost like someone's blowing bubbles into the mic; the post-chorus jumps to a whistle tone that's less Mariah Carey and more steaming teapot. An even more harrowing example: Spalexma's "We Are Charlie Kirk," which has been sarcastically memed into infinity. The nu-metal tribute to the late right-wing activist is deeply catchy and sickeningly soppy, like Creed but a lot worse. If a real person had attempted to record it, I'm convinced that he would have fainted from embarrassment. The song is an example of the entropic abominations that might catch on should AI music continue unimpeded, at scale: Spalexma, an entity whose authors aren't known, published about 280 songs in less than a year. However, in a bit of a twist, the full slopocalypse may be held off for a bit. Recently, a number of lawsuits by major labels against AI companies have ended in settlements that dictate significant reforms. One service, Udio, is now obligated to become, according to Billboard, a "walled garden" whose contents cannot be widely distributed. A deal reached in November between Suno and Warner Music Group mandates that the platform retire its current model and replace it with one trained solely on licensed data. Users will be able to remix work from artists who have opted to participate in the system, and they will now need to pay a fee to download their creations. These developments will not end AI music, but they may slightly rein in the creative and copyright free-for-all, at least temporarily. The music industry -- for obvious reasons -- wants to control AI tools, making it harder, or at least costlier, for amateurs to jump its gates. But the generative possibilities and consumer demand demonstrated in the brief history of AI music to date aren't going to be forgotten. A cultural countermovement that emphasizes flesh-and-blood talent and craft seems inevitable -- but so is a future for recorded music that grows more crowded and chaotic with each day. In that way, too, AI music is accelerating something very human: competition.

[2]

Opinion | Will Creative Work Survive A.I.?

The authors are sociologists who study the impacts of technology on society and culture. It's a perilous moment for creative life in America. While supporting oneself as an artist has never been easy, the power of generative A.I. is pushing creative workers to confront an uncomfortable question: Is there a place for paid creative work within late capitalism? And what will happen to our cultural landscape if the answer turns out to be no? As sociologists who study the relationship between technology and society, we've spent the last year posing questions to creative workers about A.I. We've talked to book authors, screenwriters, voice actors and visual artists. We've interviewed labor leaders, lawyers and technologists. Our takeaway from these conversations: What A.I. imperils is not human creativity itself but the ability to make a living from creative endeavor. The threat is monumental but the outcome is not inevitable. The actions that artists, audiences and regulators take in the next few years will shape the future of the arts for a long time to come. In a short span of time, A.I.-generated content has become ubiquitous. Prose written in A.I.'s unmistakably tedious style is pervasive, while in recent months, newer tools like Sora 2 and Suno have filled the internet with hit country songs and squishy mochi-ball cats. The question that often surrounds the introduction of a generative A.I. model is whether or not it's capable of producing art at a level that competes with humans. But the creative workers we spoke with were largely uninterested in this benchmark. If A.I. can produce work that's comparable to that of humans, they felt, that's only because it stole from them. Karla Ortiz, an illustrator, painter and concept artist, described the moment she witnessed A.I. churning out art in her style. "It felt like a gut punch," she said. "They were using my reputation, the work that I trained for decades, my whole life to do, and they were just using it to provide their clients with imagery that tries to mimic me." The proponents of A.I. often claim that, as good as it may get, the technology will never be able to match the talent and ingenuity of superlative human-made art. Amit Gupta is the co-founder of Sudowrite, an A.I. tool designed for writing. He believes that A.I. "will help us get to the 80 percent mark, maybe the 90 percent mark" of human writing quality, "but we're still going to be able to discern that last bit." Anyone with an iPhone can take a very good photo, Mr. Gupta has pointed out, but "there are still photographs that hang in museums; they're not the photographs that you and I took." Sam Altman, the chief executive of OpenAI, similarly talked about how A.I. will eventually replace the "median human" in most fields, but not the top performers. However, there's a problem with this line of reasoning: Sui generis artistic prodigies are few and far between. Artists, like most people trying to do something hard, tend to get better with lots of practice. Someone who is, to borrow Mr. Altman's phrase, a "median" writer in their 20s might turn into a great one by their 40s by putting in ample time and work. The creative grunt work that A.I. stands to replace most quickly is what helps emerging artists improve, not to mention pay their bills. In the early years of her career, Ms. Ortiz supported herself coloring comics and making art for video game companies. Coming from a lower-middle-class background in Puerto Rico, Ms. Ortiz said, she "would have not been able to live as an artist had I not had those jobs that a lot of folks today can't find" because the would-be employers use A.I. instead. If an A.I. colors comics, takes notes in the TV writers' room, and sifts through the slush pile at a publishing house, how will young creative workers master their medium -- and scrape together a living while doing so? This is not a novel phenomenon; the starving artist is a cliché for a reason. Creative and cultural labor markets have long been beset by an imbalance between supply and demand: There are more people who want to write, paint, direct, act and play music than there are paying jobs doing those things. As a result, most artists aren't paid especially well for their most creatively fulfilling work. Historically, this has advantaged those with the connections to score, say, a coveted unpaid internship at an art gallery or a film studio -- and the independent wealth to pay for food and rent while completing it. A.I. did not create these inequalities. But it may well exacerbate them if the technology eliminates the kind of entry-level jobs that allow early-career artists to make connections and a living, however meager, in artistic fields. Indeed, there is a prevailing fear that A.I. will be used as a pretext to eliminate jobs even if its outputs are unimpressive. When generative A.I. is put into actual practice, "its functionality is so limited and so disappointing and so mediocre," said Larry J. Cohen, a TV writer who serves on the A.I. task force for the Writers Guild of America East. But because A.I. is surrounded by what Mr. Cohen called "a complete reality distortion field," its mediocrity may not actually matter. Studios may use A.I. anyway because they are too nervous to miss the bandwagon. There's a scholarly term for this: institutional isomorphism. In a 1983 paper, the sociologists Paul DiMaggio and Walter Powell confronted an apparent puzzle: Why do organizations in a field so often resemble one another in structure, practices and products, even when it might be advantageous to differentiate themselves? Mr. DiMaggio and Mr. Powell argued that when organizations are operating in an environment of uncertainty, especially one in which "technologies are poorly understood," they look to see what other organizations are doing and copy them. The result of this mimicry is that over time, certain modes of operation become taken for granted as the correct and legitimate ones within an organization, even if they do little to advance its aims. Given that generative A.I. certainly qualifies as a "poorly understood" technology, we shouldn't be surprised to see this kind of isomorphic process unfolding within media industries. In contract negotiations for W.G.A.E. unions, the guild's executive director, Sam Wheeler, has seen media companies resist demands for A.I.-related worker protections with a stubbornness usually reserved for dollars-and-cents issues, such as employee health care costs. Companies dug their heels in about A.I. even when they seemed to have no concrete ideas about how they would actually use it. Mr. Wheeler has been struck by how "the lack of a plan" has been coupled with "the certainty that one will present itself." And when that plan eventually emerges, the last thing executives will want is to be hamstrung by union rules. While contending with media companies that seem hellbent on deploying A.I., guilds and unions are also trying to educate audiences about the differences between human and A.I.-generated works, in the hope that they will place a higher value on human-created art and have an easier time finding it. For example, the Authors Guild has pioneered a "Human Authored" certification, which writers can obtain by attesting that their book has at most minimal use of A.I. A certification like this is premised on the notion -- or perhaps just the fervent hope -- that audiences will spurn machine-generated art in favor of its human-made counterpart. But Simon Rich, an author, screenwriter and playwright isn't so sure. "There will always be people who see art more as a form of communication and who make art and enjoy art because they crave that spiritual connection with another human soul," he said -- similar to the way that some people will pay a premium for free-range organic eggs or shoes that were handcrafted in Italy. Yet he questions how many of those people there are. Will they be sufficient to support even a midsize industry? Mr. Rich sees a possible future where what we now think of as human-made "mainstream art" -- novels, TV, film, popular music -- will become like ballet or opera: "It's still beloved, but it really needs to rely on philanthropy to continue to exist." Faced with this bleak prospect, many creative workers are seeking out ways to A.I.-proof their careers. Several of the writers we spoke with talked about prioritizing projects that incorporate live performance, like plays and stand-up comedy, or forms of writing that are deeply personal and based on their own experiences, because these are harder to automate. Some visual artists are experimenting with technological tools like Glaze, an app that helps protect their pieces from being mimicked by A.I. Beyond these individual actions, there are also emerging collective efforts to safeguard artists' livelihoods. The best known of these are the 2023 Hollywood strikes, in which the Writers Guild of America and the Screen Actors Guild secured a number of A.I.-related protections for actors and film and TV writers. The resulting contracts stipulate that studios cannot make digital replicas of actors without their consent, nor can they force writers to use A.I. in crafting a movie script or teleplay. Then there are the lawsuits: Ms. Ortiz is a plaintiff in one of dozens of ongoing lawsuits accusing A.I. companies of copyright infringement -- one of which was recently settled by Anthropic to the tune of $1.5 billion. Artists who are involved in these lawsuits are sometimes painted as anti-tech, but most of the creative workers we've spoken to are not altogether opposed to A.I. Several of them named some mundane aspect of their daily work they'd be happy to offload to the technology. For Eden Riegel Miller, an actor who does frequent voice work for video games, it was "call-outs" -- generic multipurpose exclamations and short phrases that can be used in multiple scenes in the game (think of a character in a first-person shooter yelling "On your left" or "Going in!"). Miller sometimes finds recording call-outs "mind-numbing," not to mention vocally taxing. She wondered if there might be a role to play for A.I. here: "I bet there are a lot of actors that are like, 'Oh, can the computer scream for me? Then I can go do this other session, and my voice won't hurt? Great!'" Other artists already use A.I. to save time and energy. Recently, while working on the script for what he described as an "animated family action comedy," Mr. Rich had drafted the line, "the C.I.A. wouldn't approve the plan because it requires 10,000 megatons of nuclear power." He wasn't satisfied with this -- he wanted the line to sound more authentic to nuclear science. So he clicked over to ChatGPT, which he always keeps open now when writing, and prompted it to provide different terminology. ChatGPT suggested "10 exawatts of sustained nuclear fusion," which Mr. Rich loved -- into the draft it went. He estimates that the tool saves him about two hours a day that he used to spend looking stuff up online. In theory, it's a win-win: Mr. Rich gets more time to write, and his fans get more of his screenplays, TV scripts, short stories and humor pieces. But this sunny scenario only works if writers like Mr. Rich can continue making a living from their work -- and if there's a labor market that allows the next Simon Rich or Eden Riegel Miller to hone their craft. If A.I. continues on its current trajectory, this is precisely what's at risk. Most artists are not seeking to eliminate A.I. altogether, but instead to claim agency over the way it's trained and used. Next year key flash points will emerge in that effort, as SAG-AFTRA and the W.G.A. negotiate new contracts with Hollywood studios and streaming companies, and several A.I.-related copyright lawsuits are likely to be decided. For many of the artists we've spoken to, there's a sense of now or never: It is this moment, before A.I. and its uses are taken for granted, when they have the best shot of securing a future for paid creative work. It would be naïve to think creative workers are playing on anything resembling a level field here, given the jaw-dropping sums being invested in A.I. and the extent to which tech giants have already transformed cultural production. The A.I. industry claims that it wants to democratize creativity, but the real goal is dominance. It can seem inevitable that A.I. will rewrite the future of the arts -- a natural consequence of the tools' technical and economic momentum. But the impacts of technological change are always shaped by human action. If we believe and behave as though A.I. dominance is a foregone conclusion, we risk making it so. Instead, we should support the creative workers who are fighting for a different outcome -- and have already landed a few punches. The future of human creativity is inextricably linked to the future of creative labor. The sooner we recognize this, the better chance we have to preserve artists' livelihoods -- and human-made art itself. Let's not decide the fight is over simply because the odds are long. Caitlin Petre is an associate professor at the School of Communication and Information at Rutgers University. Julia Ticona is an assistant professor at the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We'd like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here's our email: [email protected]. Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

[3]

Musicians are deeply concerned about AI. So why are the major labels embracing it?

Companies such as Udio, Suno and Klay will let you use AI to make new music based on existing artists' work. It could mean more royalties - but many are worried This was the year that AI-generated music went from jokey curiosity to mainstream force. Velvet Sundown, a wholly AI act, generated millions of streams; AI-created tracks topped Spotify's viral chart and one of the US Billboard country charts; AI "artist" Xania Monet "signed" a record deal. BBC Introducing is usually a platform for flesh-and-blood artists trying to make it big, but an AI-generated song by Papi Lamour was recently played on the West Midlands show. And jumping up the UK Top 20 this month is I Run, a track by dance act Haven, who have been accused of using AI to imitate British vocalist Jorja Smith (Haven claim they simply asked the AI for "soulful vocal samples", and did not respond to an earlier request to comment). The worry is that AI will eventually absorb all creative works in history and spew out endless slop that will replace human-made art and drive artists into penury. Those worries are being deepened by how the major labels, once fearful of the technology, are now embracing it - and heralding a future in which ordinary listeners have a hand in co-creating music with their favourite musicians. AI music platforms analyse huge amounts of recorded music in order to learn its sounds, structures and expressions, and then allow users to create their own AI-generated music via text or speech prompts. You might ask for a moody R&B song about a breakup sung by a female vocalist, and it will come up with a decent approximation of one, because it's absorbed hundreds of such songs. Artists and labels initially saw AI as the biggest existential threat since Napster-fuelled piracy: if not a replacement for human creativity, then certainly a force that could undermine its value. Gregor Pryor, a managing partner at legal firm Reed Smith, says background music for things such as advertising, films and video games, where you're not relating to a personality as you would in pop music, "is where the real damage will be done" first of all. "People will ask: why would I pay anyone to compose anything?" Aware of the scale of the shift, last year the Recording Industry Association of America, representing the three major labels, initiated legal action against AI music companies Suno and Udio for copyright infringement, alleging they had trained their AI platforms on the labels' artists without their permission. But then there was an extraordinary about-turn. They didn't just settle the matter out of court - Universal Music Group (UMG) then partnered with Udio, and Warner Music Group (WMG) with Udio and Suno. They also have deals in place with AI company Klay, the first to get all three major labels on board, adding Sony Music (discussions with indie labels are ongoing). WMG chief executive Robert Kyncl has said these recent deals are to ensure the "protection of the rights of our artists and songwriters" and to fuel "new creative and commercial possibilities" for them, while UMG chief Lucien Grainge heralded "a healthy commercial AI ecosystem in which artists, songwriters, music companies and technology companies can all flourish and create incredible experiences for fans". Kyncl made another bold statement as to why these deals are taking place: "Now, we are entering the next phase of innovation. The democratisation of music creation." Announcing its Universal tie-in, Udio chief executive Andrew Sanchez has said Udio users will be able to "create [music] with an artist's voice and style": so not just create the aforementioned moody R&B song, but one with a specific existing artist's voice. He also says Udio will allow users to "remix and reimagine your favourite songs with AI ... take your favourite artists, songs or styles and combine them in novel ways. In our internal experimentation, the team has gotten some truly remarkable and unusual results that will definitely delight." Klay meanwhile states that "fans can mould their musical journeys in new ways", but it's essentially the same offering: a subscription service where you can manipulate the music of others, or create your own from it. Ary Attie, Klay's founder and chief executive, says his company will properly compensate artists whose work is used, and won't supplant the work of human musicians: "This technology is not going to change any of that." Klay is a rarity in that it signed up all three major labels before it started training its AI system on their music: "A core part of our philosophy," Attie says. He argues that rival AI companies - he doesn't name names - have been "acting in a way that doesn't respect the work of artists, and then being forced into a corner". Suno did not respond to an interview request; Udio claimed its executives were "extremely swamped" and therefore unable to answer questions. The current, and synchronised, messaging from labels and gen AI companies with licensing deals is that they all respect both art and artists and that their deals will reflect this. They are also positioning gen AI as the single biggest democratising leap ever in remix culture, effectively enabling everyone to become musically creative. The counterargument is that, by lowering all barriers to entry and by allowing the manipulation of a song or a musician's character at scale, it vastly devalues and negates the creative act itself. But what do musicians actually think of the prospect of their work being used to train AI, and reworked by the general public? "Everybody should be selling or licensing their voice and their skills to these companies," Dave Stewart of Eurythmics argued to me this week. "Otherwise they're just going to take it anyway." That view is directly countered by the major labels and AI companies, who have insisted artists and songwriters get to opt in to have their music made available, and if they do, get royalties when their music is used to train AI, or manipulated by users on platforms such as Udio, Suno and Klay. Others take a grimmer view about how these companies might reshape the industry. Irving Azoff, legendarily forthright artist manager and founder of the Music Artists Coalition in the US, responded to the Universal/Udio deal with biting cynicism. "We've seen this before - everyone talks about 'partnership,' but artists end up on the sidelines with scraps," he said. In the wake of the same deal, the Council of Music Makers in the UK accused the major labels of "spin" and called for a more robust set of artist-label agreements. And the European Composer and Songwriter Alliance says there is a disturbing "lack of transparency" around the deals (though more detail is likely to emerge on what users can do with any music they create, and any potential commercial uses of it). Catherine Anne Davies, who records as the Anchoress and also sits on the board of directors at the Featured Artists Coalition (FAC), has many reservations here. "Most people don't even want their work to be used for training AI," she says. "I'm on the dystopian side, or maybe what I call the realist side of things. I'm interested in the way that AI can be assistive in the creative process - if it can make us more efficient, if it can streamline our processes. But generative AI for me, in terms of creative output, is a big no-no at the moment. I'm yet to be convinced." Musician Imogen Heap feels that AI itself is not to be feared as a tool - she uses an AI she calls Mogen to listen to every aspect of her life, with a view to it being a creative partner (as explored in a recent Guardian article). To help address some of the issues, she has created Auracles, an artist-led, non-profit platform she hopes will be the place where the rights and permissions around AI are set out. It's not enough to say you're happy with your music being used by AI, she says - instead, what's needed are "permissions that grow and evolve over time". Other companies are cropping up with similar offers. "We must protect the artists at all costs," says Sean Power, chief executive of Musical AI, who aims to give musicians "an exact portion of the influence they're having on all the generative outputs" - meaning compensation every time even a tiny bit of one of their songs is used by a user of Udio et al. Terms of these deals are undisclosed, but labels are likely to be seeking settlement for any past use of their artists' copyrights as well as an advance on future use, plus an equity stake in the platform. And while artists will be able to opt out of including their work, they probably won't be consulted on these partnerships going ahead, with this lack of consultation being something that artist representative bodies such as FAC have been particularly critical of. "The big artists, the labels need to be nice to; those who have a platform will be consulted to some degree," says a music licensing expert, speaking anonymously. "The very few, who as individual artists are able to make a dent on share price, will have approval." I approached Universal, Sony and Warner about the specific concerns raised by artists here: namely limited transparency around the deals, their commercial terms and how opt-ins work; if there is a risk of gen AI undermining existing revenue sources; and if there is significant artist refusal to assign their works for gen AI training. None of the companies would comment on the record about the specifics. Though in an internal Universal memo about AI deals, sent to all staff earlier this year and seen by the Guardian, Grainge said "we will NOT license any model that uses an artist's voice or generates new songs which incorporate an artist's existing songs without their consent." The Guardian understands that labels are currently having discussions with artists and their managers to better explain how these deals will work and why they believe they can bring in additional revenue, although they will need to convince artists that gen AI will not damage other sources of income, notably from streaming. But it isn't clear whether consumers will actually pay to play around with music in the way Udio and others hope they will. AI is the single biggest hype category in Silicon Valley right now, with an average of $2bn of venture capital investment going into AI companies every week in the first half of this year. Sundar Pichai, chief executive of Alphabet (parent company of Google), recently warned of the catastrophic domino effect across the tech sector if this AI bubble bursts, a concern the Bank of England also recently raised. Reed Smith's Gregor Pryor argues that AI music could, counterintuitively, end up being positive for human musicians. "By its nature, AI is derivative and cannot create new music," he says. "Some investors in music catalogues that I speak to say it's good for artists, because music 'verified' as created by humans will have greater value." Artists will frame their work as having an invaluable human essence, their music speaking entirely from the heart, but it will become incrementally more difficult for the casual listener to distinguish between music created by a human and that created by AI. The Guardian understands that radio stations and DJs are currently extremely nervous about AI-powered music slipping through their quality filters, effectively hoodwinking them and hanging question marks over how their playlists work. The example of Papi Lamour might force them to do much greater due diligence on what they put forward for airplay consideration. Or they could be the first trickles of a flood that roars through radio and streaming services as the boundaries between AI and human-created music crumble. Davies is especially worried about artists not thinking through the long-term implications of licensing to AI services. "We cannot think of ourselves selfishly as entities that will be unaffected, because the entire ecosystem will experience a knock-on effect financially. What about your fellow composers and creators? But also what about the generations to come after? Are we fucking this completely, just to make sure that we can pay our mortgages now?" AI's current level of sophistication means it is really producing composites of existing music, creating a Frankenstein's monster of melodies. However, when AGI (artificial general intelligence) finally arrives, with Anthropic co-founder Dario Amodei suggesting that could happen as soon as next year, we will be catapulted into an exhilarating and terrifying realm of uncertainty for the future and the purpose of human-created art. "It's literally happening under our noses," warns Davies. "We should be so much more concerned than we are."

Share

Share

Copy Link

Warner Music Group, Universal Music Group, and Sony Music have partnered with AI music platforms Suno, Udio, and Klay after initially suing them for copyright infringement. The deals promise to democratize music creation while protecting artists' rights, but musicians worry about the impact on creative work and their livelihoods as AI-generated tracks accumulate millions of streams.

Major Labels Pivot From Legal Action to Partnership

The music industry witnessed a dramatic reversal in 2025 as major labels shifted from fighting AI music platforms to embracing them. After the Recording Industry Association of America initiated copyright infringement lawsuits against Suno and Udio last year, alleging they trained their AI systems on artists' work without permission, the three major labels executed an extraordinary about-turn

3

. Universal Music Group partnered with Udio, Warner Music Group signed deals with both Udio and Suno, and all three major labels—including Sony Music—joined forces with Klay, marking the first time an AI platform secured agreements across the entire industry3

.Warner Music Group chief executive Robert Kyncl framed these licensing deals as necessary to ensure "protection of the rights of our artists and songwriters" while creating "new creative and commercial possibilities"

3

. Universal Music Group chief Lucien Grainge heralded "a healthy commercial AI ecosystem in which artists, songwriters, music companies and technology companies can all flourish"3

. Kyncl made an even bolder claim, declaring that the industry is "entering the next phase of innovation" through the "democratisation of music creation"3

.AI-Generated Music Achieves Mainstream Success

This year marked AI's transition from experimental novelty to commercial force within the music industry. Velvet Sundown, a wholly AI act, generated millions of streams, while AI-created tracks topped Spotify's viral chart and one of the US Billboard country charts

3

. Xania Monet, an AI "singer" created by 31-year-old Mississippi entrepreneur Telisha "Nikki" Jones using Suno to convert autobiographical poetry into R&B, was reportedly offered a $3 million record contract after achieving streaming success1

.The technology behind these platforms is straightforward yet powerful. Suno, which raised $250 million in funding and achieved a $2.5 billion valuation, is trained on a vast body of historical recordings and can synthesize plausible renditions of any genre or style users request

1

. Newer tools like Sora 2 and Suno have filled the internet with content ranging from hit country songs to visual creations2

. Udio chief executive Andrew Sanchez announced that users will be able to "create with an artist's voice and style" and "remix and reimagine your favourite songs with AI"3

.Human Creativity Under Threat From Generative AI

Source: NYT

While corporate messaging emphasizes democratization, musicians express deep concern about the impact on creative work and their ability to sustain creative livelihoods. Karla Ortiz, an illustrator and concept artist, described witnessing AI churning out art in her style as "a gut punch," explaining that "they were using my reputation, the work that I trained for decades, my whole life to do"

2

. The fundamental question confronting artists isn't whether AI can match human creativity, but whether paid creative work can survive within the current economic system2

.The threat extends beyond established artists to emerging talent. Ortiz supported herself early in her career by coloring comics and making art for video game companies—jobs that "a lot of folks today can't find" because employers use AI instead

2

. This creative grunt work helps emerging artists improve their craft and pay bills while mastering their medium. If AI colors comics, takes notes in TV writers' rooms, and handles entry-level creative tasks, the pathway for young songwriters and musicians to develop their skills while earning a living may disappear entirely2

.Related Stories

Copyright and Compensation Questions Remain Unresolved

The debate over whether AI music constitutes copyright infringement continues despite the new partnerships. Suno argued in its response to lawsuits that "the outputs generated by Suno are new sounds," positioning the technology as transformative rather than derivative

1

. However, this raises fundamental questions about what it means to create music. If a human types a keyword that generates a song, how much credit should they receive? The record industry faces uncertainty about where to draw lines around creative attribution and royalties1

.Klay founder and chief executive Ary Attie distinguished his company by signing all three major labels before training its AI system on their music, arguing this approach respects artists' rights

3

. He claims Klay will properly compensate artists whose work is used and won't supplant human musicians3

. Yet Gregor Pryor, a managing partner at legal firm Reed Smith, predicts background music for advertising, films, and video games represents where "the real damage will be done" first, as clients ask why they should pay anyone to compose anything3

.The Future of Artists and the Streaming Service Economy

Sociologists studying the relationship between technology and society warn that what AI imperils is not human creativity itself but the ability to make a living from creative endeavor

2

. The actions that artists, audiences, and regulators take in the next few years will shape the future of the arts for decades2

. iHeartRadio responded to consumer sentiment by rolling out a "Guaranteed Human" tagline, with president Tom Poleman announcing the company won't employ AI personalities or play songs with purely synthetic lead vocals—citing research showing 90 percent of consumers want their media from real humans1

.The livelihoods of human artists face pressure not just from AI replacing their work, but from the technology exacerbating existing inequalities in creative labor markets. There have always been more people wanting to write, paint, direct, and play music than paying jobs available

2

. AI didn't create these imbalances, but it may eliminate the entry-level jobs that allow early-career artists to make connections and earn modest livings in artistic fields2

. As AI opens what one observer called "a Pandora's box," it tests what society truly values about music—whether we prize the human experience embedded in creation or simply the end product1

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic takes Pentagon to court over unprecedented supply chain risk designation

Policy and Regulation

3

Meta smart glasses face lawsuit and UK probe after workers watched intimate user footage

Policy and Regulation