Judge Skeptical of Meta's Fair Use Defense in AI Copyright Case

6 Sources

6 Sources

[1]

Judge on Meta's AI training: "I just don't understand how that can be fair use

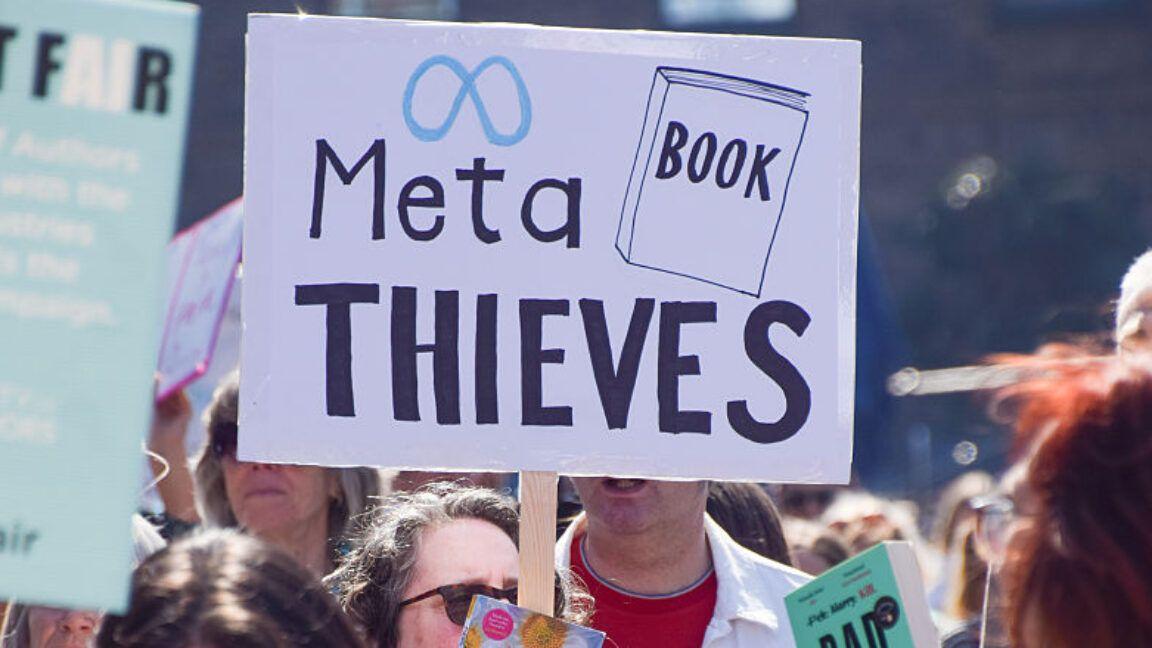

A judge who may be the first to rule on whether AI training data is fair use appeared skeptical Thursday at a hearing where Meta faced off with book authors over the social media company's alleged copyright infringement. Meta, like most AI companies, holds that training must be deemed fair use, or else the entire AI industry could face immense setbacks, wasting precious time negotiating data contracts while falling behind global rivals. Meta urged the court to rule that AI training is a transformative use that only references books to create an entirely new work that doesn't replicate authors' ideas or replace books in their markets. At the hearing that followed after both sides requested summary judgment, however, Judge Vince Chhabria pushed back on Meta attorneys arguing that the company's Llama AI models posed no threat to authors in their markets, Reuters reported. "You have companies using copyright-protected material to create a product that is capable of producing an infinite number of competing products," Chhabria said. "You are dramatically changing, you might even say obliterating, the market for that person's work, and you're saying that you don't even have to pay a license to that person." Declaring, "I just don't understand how that can be fair use," the shrewd judge apparently stoked little response from Meta's attorney, Kannon Shanmugam, apart from a suggestion that any alleged threat to authors' livelihoods was "just speculation," Wired reported. Authors may need to sharpen their case, which Chhabria warned could be "taken away by fair use" if none of the authors suing, including Sarah Silverman, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Richard Kadrey, can show "that the market for their actual copyrighted work is going to be dramatically affected." Determined to probe this key question, Chhabria pushed authors' attorney, David Boies, to point to specific evidence of market harms that seemed noticeably missing from the record. "It seems like you're asking me to speculate that the market for Sarah Silverman's memoir will be affected by the billions of things that Llama will ultimately be capable of producing," Chhabria said. "And it's just not obvious to me that that's the case." But if authors can prove fears of market harms are real, Meta might struggle to win over Chhabria, and that could set a precedent impacting copyright cases challenging AI training on other kinds of content. The judge repeatedly appeared to be sympathetic to authors, suggesting that Meta's AI training may be a "highly unusual case" where even though "the copying is for a highly transformative purpose, the copying has the high likelihood of leading to the flooding of the markets for the copyrighted works." And when Shanmugam argued that copyright law doesn't shield authors from "protection from competition in the marketplace of ideas," Chhabria resisted the framing that authors weren't potentially being robbed, Reuters reported. "But if I'm going to steal things from the marketplace of ideas in order to develop my own ideas, that's copyright infringement, right?" Chhabria responded. Wired noted that he asked Meta's lawyers, "What about the next Taylor Swift?" If AI made it easy to knock off a young singer's sound, how could she ever compete if AI produced "a billion pop songs" in her style? In a statement, Meta's spokesperson reiterated the company's defense that AI training is fair use. "Meta has developed transformational open source AI models that are powering incredible innovation, productivity, and creativity for individuals and companies," Meta's spokesperson said. "Fair use of copyrighted materials is vital to this. We disagree with Plaintiffs' assertions, and the full record tells a different story. We will continue to vigorously defend ourselves and to protect the development of GenAI for the benefit of all." Meta's torrenting seems "messed up" Some have pondered why Chhabria appeared so focused on market harms, instead of hammering Meta for admittedly illegally pirating books that it used for its AI training, which seems to be obvious copyright infringement. According to Wired, "Chhabria spoke emphatically about his belief that the big question is whether Meta's AI tools will hurt book sales and otherwise cause the authors to lose money," not whether Meta's torrenting of books was illegal. The torrenting "seems kind of messed up," Chhabria said, but "the question, as the courts tell us over and over again, is not whether something is messed up but whether it's copyright infringement." It's possible that Chhabria dodged the question for procedural reasons. In a court filing, Meta argued that authors had moved for summary judgment on Meta's alleged copying of their works, not on "unsubstantiated allegations that Meta distributed Plaintiffs' works via torrent." In the court filing, Meta alleged that even if Chhabria agreed that the authors' request for "summary judgment is warranted on the basis of Meta's distribution, as well as Meta's copying," that the authors "lack evidence to show that Meta distributed any of their works." According to Meta, authors abandoned any claims that Meta's seeding of the torrented files served to distribute works, leaving only claims about Meta's leeching. Meta argued that the authors "admittedly lack evidence that Meta ever uploaded any of their works, or any identifiable part of those works, during the so-called 'leeching' phase," relying instead on expert estimates based on how torrenting works. It's also possible that for Chhabria, the torrenting question seemed like an unnecessary distraction. Former Meta attorney Mark Lumley, who quit the case earlier this year, told Vanity Fair that the torrenting was "one of those things that sounds bad but actually shouldn't matter at all in the law. Fair use is always about uses the plaintiff doesn't approve of; that's why there is a lawsuit." Lumley suggested that court cases mulling fair use at this current moment should focus on the outputs, rather than the training. Citing the ruling in a case where Google Books scanning books to share excerpts was deemed fair use, Lumley argued that "all search engines crawl the full Internet, including plenty of pirated content," so there's seemingly no reason to stop AI crawling. But the Copyright Alliance, a nonprofit, non-partisan group supporting the authors in the case, in a court filing alleged that Meta, in its bid to get AI products viewed as transformative, is aiming to do the opposite. "When describing the purpose of generative AI," Meta allegedly strives to convince the court to "isolate the 'training' process and ignore the output of generative AI," because that's seemingly the only way that Meta can convince the court that AI outputs serve "a manifestly different purpose from Plaintiffs' books," the Copyright Alliance argued. "Meta's motion ignores what comes after the initial 'training' -- most notably the generation of output that serves the same purpose of the ingested works," the Copyright Alliance argued. And the torrenting question should matter, the group argued, because unlike in Google Books, Meta's AI models are apparently training on pirated works, not "legitimate copies of books." Chhabria will not be making a snap decision in the case, planning to take his time and likely stressing not just Meta, but every AI company defending training as fair use the longer he delays. Understanding that the entire AI industry potentially has a stake in the ruling, Chhabria apparently sought to relieve some tension at the end of the hearing with a joke, Wired reported. "I will issue a ruling later today," Chhabria said. "Just kidding! I will take a lot longer to think about it."

[2]

A Judge Says Meta's AI Copyright Case Is About 'the Next Taylor Swift'

Meta's contentious AI copyright battle is heating up -- and the court may be close to a ruling. Meta's copyright battle with a group of authors, including Sarah Silverman and Ta-Nehisi Coates, will turn on the question of whether the company's AI tools produce works that can cannibalize the authors' book sales. US District Court Judge Vince Chhabria spent several hours grilling lawyers from both sides after they each filed motions for partial summary judgement, meaning they want Chhabria to rule on specific issues of the case rather than leaving each one to be decided at trial. The authors allege that Meta illegally used their work to build its generative AI tools, emphasizing that the company pirated their books through "shadow libraries" like LibGen. The social media giant is not denying that it used the work or that it downloaded books from shadow libraries en masse, but insists that its behavior is shielded by the "fair use" doctrine, an exception in US copyright law that allows for permissionless use of copyrighted work in certain cases, including parody, teaching, and news reporting. If Chhabria grants either motion, he'll issue a ruling before the case goes to trial -- and likely set an important precedent shaping how courts deal with generative AI copyright cases moving forward. Kadrey v. Meta is one of the dozens of lawsuits filed against AI companies that are currently winding through the US legal system. While the authors were heavily focused on the piracy element of the case, Chhabria spoke emphatically about his belief that the big question is whether Meta's AI tools will hurt book sales and otherwise cause the authors to lose money. "If you are dramatically changing, you might even say obliterating the market for that person's work, and you're saying that you don't even have to pay a license to that person to use their work to create the product that's destroying the market for their work -- I just don't understand how that can be fair use," he told Meta lawyer Kannon Shanmugam. (Shanmugam responded that the suggested effect was "just speculation.") Chhabria and Shanmugam went on to debate whether Taylor Swift would be harmed if her music was fed into an AI tool that then created billions of robotic knockoffs. Chhabria questioned how this would impact less-established songwriters. "What about the next Taylor Swift?" he asked, arguing that a "relatively unknown artist" whose work was ingested by Meta would likely have their career hampered if the model produced "a billion pop songs" in their style. At times, it sounded like the case was the authors' to lose, with Chhabria noting that Meta was "destined to fail" if the plaintiffs could prove that Meta's tools created similar works that cratered how much money they could make from their work. But Chhabria also stressed that he was unconvinced the authors would be able to show the necessary evidence. When he turned to the authors' legal team, led by high-profile attorney David Boies, Chhabria repeatedly asked whether the plaintiffs could actually substantiate accusations that Meta's AI tools were likely to hurt their commercial prospects. "It seems like you're asking me to speculate that the market for Sarah Silverman's memoir will be affected," he told Boies. "It's not obvious to me that is the case."

[3]

Meta lawsuit poses first big test of AI copyright battle

Meta will fight a group of US authors in court on Thursday in one of the first big legal tests of whether tech companies can use copyrighted material to train their powerful artificial intelligence models. The case, which has been brought by about a dozen authors including Ta-Nehisi Coates and Richard Kadrey, is centred around the $1.4tn social media giant's use of LibGen, a so-called shadow library of millions of books, academic articles and comics, to train its Llama AI models. The ruling will have wide-reaching implications in the fierce copyright battle between artists and AI groups and is one of a flurry of lawsuits around the world that allege technology groups are using content without permission. Microsoft, OpenAI and Anthropic also face similar legal challenges over the data used to train the large language models behind their popular AI chatbots, such as ChatGPT and Claude. "AI models have been trained on hundreds of thousands if not millions of books, downloaded from well-known pirated sites, this was not accidental," said Mary Rasenberger, chief executive of the Authors Guild. "Authors should have gotten license fees for that." Meta has argued that using copyrighted materials to train LLMs is "fair use" if it is used to develop a transformative technology, even if it is from pirated databases. LibGen hosts much of its content without permission from the rights holders. In legal filings, Meta notes that "use was fair irrespective of its method of acquisition". According to the court filings, the US tech giant engaged in early discussions with book publishers exploring options to license material to train its models. The plaintiffs allege that Meta abandoned this because the works were available through LibGen, leading to a loss of compensation and control for authors. In the discovery, Meta said, "if we license once [sic] single book, we won't be able to lean into the fair use strategy". Meta argues in its defence that there was no market for licensing such works for this purpose. However, emails unearthed in the court's discovery process show Meta employees suggesting they were entering a legal grey area and appearing to discuss how to avoid scrutiny when using LibGen, according to the claim documents. In one email from January last year, Joelle Pineau, Meta's recently departed head of AI research lab FAIR, recommended using the LibGen data set. In a subsequent email, Sony Theakanath, a director of product at Meta, said "in no case would we disclose publicly that we had trained on libgen". The email had a subtitle "legal risk", in which the risks or details below it have been redacted, as well as another subtitle "policy risks", which contained "copyright and IP". The email suggested mitigations such as "remove data clearly marked as pirated/stolen". The case comes as Meta is pouring billions of dollars to become an "AI leader", developing its Llama models to compete against OpenAI, Microsoft, Google and Elon Musk's xAI. "There is a tremendous amount of uncertainty right now," said Chris Mammen, a partner at law firm Womble Bond Dickinson, highlighting that copyright cases can take years to reach a conclusion. "It is extremely important to get these things resolved. Things are going to continue happening in the world at the breakneck pace that technology and our economy are developing," he added. Another contention in the lawsuit involves the method that plaintiffs allege Meta used to acquire the LibGen database, known as torrenting, which often uploads the content to others using the software while downloading the materials. It is stated in the court documents that Meta torrented the work but attempted to limit its distribution. However, it has yet to provide assurances that this was entirely prevented, and some evidence relating to outbound data was deleted, according to information from the discovery process. "Meta has developed transformational open source AI models that are powering incredible innovation, productivity, and creativity for individuals and companies. Fair use of copyrighted materials is vital to this," Meta said in a statement. "We disagree with [the] plaintiffs' assertions, and the full record tells a different story. We will continue to vigorously defend ourselves and to protect the development of GenAI for the benefit of all."

[4]

Judge in Meta case weighs key question for AI copyright lawsuits

May 1 (Reuters) - A federal judge in San Francisco will hear arguments on Thursday from Meta Platforms (META.O), opens new tab and a group of authors in the first court hearing over a pivotal question in high-stakes copyright cases over AI training. U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria will consider Meta's request for a pretrial ruling that it made "fair use" of books from writers including Junot Diaz and comedian Sarah Silverman to train its Llama large language model. The fair use question hangs over lawsuits brought by authors, news outlets and other copyright owners against companies including Meta, OpenAI and Anthropic. The legal doctrine allows for the use of copyrighted work without the copyright owner's permission under some circumstances. The authors in the Meta case sued in 2023, arguing the company used pirated versions of their books to train Llama without permission or compensation. Technology companies have said that being forced to pay copyright holders for their content could hamstring the burgeoning, multi-billion dollar AI industry. The defendants say their AI systems make fair use of copyrighted material by studying it to learn to create new, transformative content. Plaintiffs in the cases counter that AI companies unlawfully copy their work to generate competing content that threatens their livelihoods. Meta told Chhabria in March that it used the authors' material transformatively, to teach Llama to "serve as a personal tutor on nearly any subject, assist with creative ideation, and help users to generate business reports, translate conversations, analyze data, write code, and compose poems or letters to friends." "What it does not do is replicate Plaintiffs' books or substitute for reading them," Meta said. The authors told Chhabria in a court filing that Meta used their books "for their expressive content -- the very subject matter copyright law protects." "Under a straightforward application of existing copyright law, Meta is liable for massive copyright infringement," the authors said. Reporting by Blake Brittain in Washington Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles., opens new tab Suggested Topics:Litigation Blake Brittain Thomson Reuters Blake Brittain reports on intellectual property law, including patents, trademarks, copyrights and trade secrets, for Reuters Legal. He has previously written for Bloomberg Law and Thomson Reuters Practical Law and practiced as an attorney.

[5]

US federal judge on Meta's AI copyright fair use argument: 'You are dramatically changing, you might even say obliterating, the market for that person's work'

Comedian Sarah Silverman and two other authors filed copyright infringement lawsuits against Meta Platforms and OpenAI back in 2023, alleging pirated versions of their works were used without permission to train AI language models. Meta has since argued that such usage falls under fair use doctrine (via Reuters), but US federal district judge Vince Chhabria seems to have been less than impressed by the defence: "You have companies using copyright-protected material to create a product that is capable of producing an infinite number of competing products," said Chhabria to Meta's attorneys in a San Francisco court last Thursday. "You are dramatically changing, you might even say obliterating, the market for that person's work, and you're saying that you don't even have to pay a license to that person... I just don't understand how that can be fair use." Under US copyright law, fair use is a doctrine that permits the use of copyrighted material without explicit permission of the copyright holder, Examples of fair use include usage for the purpose of criticism, news reporting, teaching, and research. It can be used as an affirmative defence in response to copyright infringement claims, although several factors are considered in judging whether usage of copyrighted works falls under fair use -- including the effect of the use of said works on the market (or potential markets) they exist in. Meta has argued that its AI systems make fair use of copyrighted material by studying it, in order to make "transformative" new content. However, judge Chhabria appears to disagree: "This seems like a highly unusual case in the sense that though the copying is for a highly transformative purpose, the copying has the high likelihood of leading to the flooding of the markets for the copyrighted works," said Chhabria. Meta attorney Kannon Shanmugam then reportedly argued that copyright owners are not entitled to protection from competition in "the marketplace of ideas", to which Chhabira responded: "But if I'm going to steal things from the marketplace of ideas in order to develop my own ideas, that's copyright infringement, right?" However, Chhabria also appears to have taken issue with the plaintiffs attorney, David Boies, in regards to the lawsuit potentially not providing enough evidence to address the potential market impacts of Meta's alleged conduct. "It seems like you're asking me to speculate that the market for Sarah Silverman's memoir will be affected by the billions of things that Llama [Meta's AI model] will ultimately be capable of producing," said Chhabria. "And it's just not obvious to me that that's the case." All to play for, then, although by the looks of things judge Chhabria seems determined to hold both sides to proper account. It also gives me a chance to publish a line I've always wanted to write: The case continues. Yep, it's about as satisfying as I thought.

[6]

Judge in Meta case warns AI could 'obliterate' market for original works

In a San Francisco court, a federal judge questioned Meta's claim that using copyrighted works to train AI models is "fair use". The judge voiced concerns that this could devastate the market for original content, as AI can produce infinite competing products without licensing fees. Authors and news outlets have filed lawsuits against Meta, OpenAI, and Anthropic over this issue.A sceptical federal judge in San Francisco on Thursday questioned Meta Platforms' argument that it can legally use copyrighted works without permission to train its artificial intelligence models. In the first court hearing on a key question for the AI industry, U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria grilled lawyers for both sides over Meta's request for a ruling that it made "fair use" of books by Junot Diaz, comedian Sarah Silverman and others to train its Llama large language model. "You have companies using copyright-protected material to create a product that is capable of producing an infinite number of competing products," Chhabria told Meta's attorneys. "You are dramatically changing, you might even say obliterating, the market for that person's work, and you're saying that you don't even have to pay a license to that person." "I just don't understand how that can be fair use," Chhabria said. The fair use question hangs over lawsuits brought by authors, news outlets and other copyright owners against companies including Meta, OpenAI and Anthropic. The legal doctrine allows for the use of copyrighted work without the copyright owner's permission under some circumstances. The authors in the Meta case sued in 2023, arguing the company used pirated versions of their books to train Llama without permission or compensation. Technology companies have said that being forced to pay copyright holders for their content could hamstring the burgeoning, multi-billion dollar AI industry. The defendants say their AI systems make fair use of copyrighted material by studying it to learn to create new, transformative content. Plaintiffs counter that AI companies unlawfully copy their work to generate competing content that threatens their livelihoods. Chhabria on Thursday acknowledged that Meta's use may have been transformative, but said it still may not have been fair. "This seems like a highly unusual case in the sense that though the copying is for a highly transformative purpose, the copying has the high likelihood of leading to the flooding of the markets for the copyrighted works," Chhabria said. Meta attorney Kannon Shanmugam said copyright owners are not entitled to "protection from competition in the marketplace of ideas." "But if I'm going to steal things from the marketplace of ideas in order to develop my own ideas, that's copyright infringement, right?," Chhabria responded. Chhabria also told the plaintiffs' attorney David Boies that the lawsuit may not have adequately addressed the potential market impacts of Meta's conduct. "I think it is taken away by fair use unless a plaintiff can show that the market for their actual copyrighted work is going to be dramatically affected," Chhabria said. Chhabria prodded Boies for evidence that Llama's creations would affect the market for the authors' books specifically. "It seems like you're asking me to speculate that the market for Sarah Silverman's memoir will be affected by the billions of things that Llama will ultimately be capable of producing," Chhabria said. "And it's just not obvious to me that that's the case."

Share

Share

Copy Link

A federal judge expresses doubts about Meta's fair use argument in a copyright infringement lawsuit over AI training data, potentially setting a precedent for the AI industry.

Judge Challenges Meta's Fair Use Defense in AI Copyright Case

In a pivotal hearing that could set a precedent for AI copyright cases, U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria expressed skepticism towards Meta's fair use defense in a lawsuit brought by authors including Sarah Silverman, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Richard Kadrey

1

2

. The case, centered on Meta's use of copyrighted books to train its Llama AI models, is one of the first major legal tests of whether tech companies can use copyrighted material for AI training without permission3

.Meta's Fair Use Argument Under Scrutiny

Meta, like many AI companies, argues that training AI models on copyrighted works falls under fair use, claiming it's a transformative process that creates entirely new works without replicating authors' ideas

1

. However, Judge Chhabria pushed back on this assertion, stating:"You have companies using copyright-protected material to create a product that is capable of producing an infinite number of competing products. You are dramatically changing, you might even say obliterating, the market for that person's work, and you're saying that you don't even have to pay a license to that person... I just don't understand how that can be fair use."

1

5

The Piracy Question and Market Impact

While the authors' lawsuit emphasizes Meta's alleged piracy of books through "shadow libraries" like LibGen, Judge Chhabria focused more on the potential market harm to authors

2

3

. He questioned how AI-generated content could impact emerging artists, using the example of "the next Taylor Swift" whose style could be replicated by AI producing "a billion pop songs"2

.Meta's Defense and Author's Challenge

Meta's attorney, Kannon Shanmugam, argued that any alleged threat to authors' livelihoods was "just speculation"

1

. However, the judge seemed unconvinced, suggesting that if authors can prove real market harms, Meta might struggle to win the case1

.Implications for the AI Industry

The outcome of this case could have far-reaching implications for the AI industry. Companies like Microsoft, OpenAI, and Anthropic face similar legal challenges over data used to train their AI models

3

. Mary Rasenberger, CEO of the Authors Guild, emphasized the scale of the issue: "AI models have been trained on hundreds of thousands if not millions of books, downloaded from well-known pirated sites, this was not accidental."3

Related Stories

Meta's Internal Discussions Revealed

Court filings revealed internal discussions at Meta about the legal risks of using LibGen data. In one email, a Meta director suggested, "in no case would we disclose publicly that we had trained on libgen," indicating awareness of potential legal and policy risks

3

.The Road Ahead

As the case progresses, both sides face challenges. Judge Chhabria warned the authors that their case could be "taken away by fair use" if they can't demonstrate significant market impact

1

. Meanwhile, Meta must convince the court that its use of copyrighted material is truly transformative and doesn't harm authors' markets1

2

.This case represents a critical juncture for the AI industry, potentially setting the stage for how copyright law will be applied to AI training data in the future

3

4

. As Chris Mammen, a partner at law firm Womble Bond Dickinson, noted, "There is a tremendous amount of uncertainty right now... It is extremely important to get these things resolved."3

References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Meta Faces Legal Scrutiny Over Alleged Copyright Infringement in AI Training

11 Mar 2025•Policy and Regulation

Judges Side with AI Companies in Copyright Cases, but Leave Door Open for Future Challenges

25 Jun 2025•Policy and Regulation

Legal Battles Over AI Training: Courts Rule on Fair Use, Authors Fight Back

15 Jul 2025•Policy and Regulation

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens to cut Anthropic's $200M contract over AI safety restrictions in military ops

Policy and Regulation

2

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI closes in on $100 billion funding round with $850 billion valuation as spending plans shift

Business and Economy