AI's Energy Paradox: How Data Centers Are Reshaping Global Power Demand and Climate Goals

5 Sources

5 Sources

[1]

How artificial intelligence can help achieve a clean energy future

Caption: Researchers at MIT and elsewhere are investigating how AI can be harnessed to support the clean energy transition. There is growing attention on the links between artificial intelligence and increased energy demands. But while the power-hungry data centers being built to support AI could potentially stress electricity grids, increase customer prices and service interruptions, and generally slow the transition to clean energy, the use of artificial intelligence can also help the energy transition. For example, use of AI is reducing energy consumption and associated emissions in buildings, transportation, and industrial processes. In addition, AI is helping to optimize the design and siting of new wind and solar installations and energy storage facilities. On electric power grids, using AI algorithms to control operations is helping to increase efficiency and reduce costs, integrate the growing share of renewables, and even predict when key equipment needs servicing to prevent failure and possible blackouts. AI can help grid planners schedule investments in generation, energy storage, and other infrastructure that will be needed in the future. AI is also helping researchers discover or design novel materials for nuclear reactors, batteries, and electrolyzers. Researchers at MIT and elsewhere are actively investigating aspects of those and other opportunities for AI to support the clean energy transition. At its 2025 research conference, MITEI announced the Data Center Power Forum, a targeted research effort for MITEI member companies interested in addressing the challenges of data center power demand. Controlling real-time operations Customers generally rely on receiving a continuous supply of electricity, and grid operators get help from AI to make that happen -- while optimizing the storage and distribution of energy from renewable sources at the same time. But with more installation of solar and wind farms -- both of which provide power in smaller amounts, and intermittently -- and the growing threat of weather events and cyberattacks, ensuring reliability is getting more complicated. "That's exactly where AI can come into the picture," explains Anuradha Annaswamy, a senior research scientist in MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering and director of MIT's Active-Adaptive Control Laboratory. "Essentially, you need to introduce a whole information infrastructure to supplement and complement the physical infrastructure." The electricity grid is a complex system that requires meticulous control on time scales ranging from decades all the way down to microseconds. The challenge can be traced to the basic laws of power physics: electricity supply must equal electricity demand at every instant, or generation can be interrupted. In past decades, grid operators generally assumed that generation was fixed -- they could count on how much electricity each large power plant would produce -- while demand varied over time in a fairly predictable way. As a result, operators could commission specific power plants to run as needed to meet demand the next day. If some outages occurred, specially designated units would start up as needed to make up the shortfall. Today and in the future, that matching of supply and demand must still happen, even as the number of small, intermittent sources of generation grows and weather disturbances and other threats to the grid increase. AI algorithms provide a means of achieving the complex management of information needed to forecast within just a few hours which plants should run while also ensuring that the frequency, voltage, and other characteristics of the incoming power are as required for the grid to operate properly. Moreover, AI can make possible new ways of increasing supply or decreasing demand at times when supplies on the grid run short. As Annaswamy points out, the battery in your electric vehicle (EV), as well as the one charged up by solar panels or wind turbines, can -- when needed -- serve as a source of extra power to be fed into the grid. And given real-time price signals, EV owners can choose to shift charging from a time when demand is peaking and prices are high to a time when demand and therefore prices are both lower. In addition, new smart thermostats can be set to allow the indoor temperature to drop or rise -- a range defined by the customer -- when demand on the grid is peaking. And data centers themselves can be a source of demand flexibility: selected AI calculations could be delayed as needed to smooth out peaks in demand. Thus, AI can provide many opportunities to fine-tune both supply and demand as needed. In addition, AI makes possible "predictive maintenance." Any downtime is costly for the company and threatens shortages for the customers served. AI algorithms can collect key performance data during normal operation and, when readings veer off from that normal, the system can alert operators that something might be going wrong, giving them a chance to intervene. That capability prevents equipment failures, reduces the need for routine inspections, increases worker productivity, and extends the lifetime of key equipment. Annaswamy stresses that "figuring out how to architect this new power grid with these AI components will require many different experts to come together." She notes that electrical engineers, computer scientists, and energy economists "will have to rub shoulders with enlightened regulators and policymakers to make sure that this is not just an academic exercise, but will actually get implemented. All the different stakeholders have to learn from each other. And you need guarantees that nothing is going to fail. You can't have blackouts." Using AI to help plan investments in infrastructure for the future Grid companies constantly need to plan for expanding generation, transmission, storage, and more, and getting all the necessary infrastructure built and operating may take many years, in some cases more than a decade. So, they need to predict what infrastructure they'll need to ensure reliability in the future. "It's complicated because you have to forecast over a decade ahead of time what to build and where to build it," says Deepjyoti Deka, a research scientist in MITEI. One challenge with anticipating what will be needed is predicting how the future system will operate. "That's becoming increasingly difficult," says Deka, because more renewables are coming online and displacing traditional generators. In the past, operators could rely on "spinning reserves," that is, generating capacity that's not currently in use but could come online in a matter of minutes to meet any shortfall on the system. The presence of so many intermittent generators -- wind and solar -- means there's now less stability and inertia built into the grid. Adding to the complication is that those intermittent generators can be built by various vendors, and grid planners may not have access to the physics-based equations that govern the operation of each piece of equipment at sufficiently fine time scales. "So, you probably don't know exactly how it's going to run," says Deka. And then there's the weather. Determining the reliability of a proposed future energy system requires knowing what it'll be up against in terms of weather. The future grid has to be reliable not only in everyday weather, but also during low-probability but high-risk events such as hurricanes, floods, and wildfires, all of which are becoming more and more frequent, notes Deka. AI can help by predicting such events and even tracking changes in weather patterns due to climate change. Deka points out another, less-obvious benefit of the speed of AI analysis. Any infrastructure development plan must be reviewed and approved, often by several regulatory and other bodies. Traditionally, an applicant would develop a plan, analyze its impacts, and submit the plan to one set of reviewers. After making any requested changes and repeating the analysis, the applicant would resubmit a revised version to the reviewers to see if the new version was acceptable. AI tools can speed up the required analysis so the process moves along more quickly. Planners can even reduce the number of times a proposal is rejected by using large language models to search regulatory publications and summarize what's important for a proposed infrastructure installation. Harnessing AI to discover and exploit advanced materials needed for the energy transition "Use of AI for materials development is booming right now," says Ju Li, MIT's Carl Richard Soderberg Professor of Power Engineering. He notes two main directions. First, AI makes possible faster physics-based simulations at the atomic scale. The result is a better atomic-level understanding of how composition, processing, structure, and chemical reactivity relate to the performance of materials. That understanding provides design rules to help guide the development and discovery of novel materials for energy generation, storage, and conversion needed for a sustainable future energy system. And second, AI can help guide experiments in real time as they take place in the lab. Li explains: "AI assists us in choosing the best experiment to do based on our previous experiments and -- based on literature searches -- makes hypotheses and suggests new experiments." He describes what happens in his own lab. Human scientists interact with a large language model, which then makes suggestions about what specific experiments to do next. The human researcher accepts or modifies the suggestion, and a robotic arm responds by setting up and performing the next step in the experimental sequence, synthesizing the material, testing the performance, and taking images of samples when appropriate. Based on a mix of literature knowledge, human intuition, and previous experimental results, AI thus coordinates active learning that balances the goals of reducing uncertainty with improving performance. And, as Li points out, "AI has read many more books and papers than any human can, and is thus naturally more interdisciplinary." The outcome, says Li, is both better design of experiments and speeding up the "work flow." Traditionally, the process of developing new materials has required synthesizing the precursors, making the material, testing its performance and characterizing the structure, making adjustments, and repeating the same series of steps. AI guidance speeds up that process, "helping us to design critical, cheap experiments that can give us the maximum amount of information feedback," says Li. "Having this capability certainly will accelerate material discovery, and this may be the thing that can really help us in the clean energy transition," he concludes. "AI [has the potential to] lubricate the material-discovery and optimization process, perhaps shortening it from decades, as in the past, to just a few years." MITEI's contributions At MIT, researchers are working on various aspects of the opportunities described above. In projects supported by MITEI, teams are using AI to better model and predict disruptions in plasma flows inside fusion reactors -- a necessity in achieving practical fusion power generation. Other MITEI-supported teams are using AI-powered tools to interpret regulations, climate data, and infrastructure maps in order to achieve faster, more adaptive electric grid planning. AI-guided development of advanced materials continues, with one MITEI project using AI to optimize solar cells and thermoelectric materials. Other MITEI researchers are developing robots that can learn maintenance tasks based on human feedback, including physical intervention and verbal instructions. The goal is to reduce costs, improve safety, and accelerate the deployment of the renewable energy infrastructure. And MITEI-funded work continues on ways to reduce the energy demand of data centers, from designing more efficient computer chips and computing algorithms to rethinking the architectural design of the buildings, for example, to increase airflow so as to reduce the need for air conditioning. In addition to providing leadership and funding for many research projects, MITEI acts as a convenor, bringing together interested parties to consider common problems and potential solutions. In May 2025, MITEI's annual spring symposium -- titled "AI and energy: Peril and promise" -- brought together AI and energy experts from across academia, industry, government, and nonprofit organizations to explore AI as both a problem and a potential solution for the clean energy transition. At the close of the symposium, William H. Green, director of MITEI and Hoyt C. Hottel Professor in the MIT Department of Chemical Engineering, noted, "The challenge of meeting data center energy demand and of unlocking the potential benefits of AI to the energy transition is now a research priority for MITEI."

[2]

The energy war of the 21st century isn't about oil anymore

There was a time when the world's biggest battles over energy were fought in oil markets, through pipelines, refineries, and OPEC negotiations. Today, those battles have moved to a very different arena. Data centres. The vast, windowless warehouses that dot the edges of cities have become the defining infrastructure of the 21st century. And the scale of what is being built is nothing short of staggering. In its November report 'World Energy Outlook 2025', the International Energy Agency (IEA) revealed that the world will spend $580 billion on data centers in 2025, which is $40 billion more than the total global spending on new oil supplies. Nations have gone to war over oil. In the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-88, while territorial disputes were central, control over oil-rich border regions played a major role. In the Gulf War of 1990, Iraq's invasion of Kuwait was tied to oil. And nations around the world have gone to war for less. As the IEA report dryly notes, "This point of comparison provides a telling marker of the changing nature of modern, highly digitalised economies." It is a single sentence that captures a global pivot, that the new energy shock is not about fossil fuels at all, but about computing. Training, running, and storing AI models require enormous amounts of electricity, and demand is rising far faster than anyone anticipated. According to the IEA, electricity consumption from AI servers alone will increase fivefold by 2030, contributing to a doubling of total data-centre electricity demand worldwide. What makes this even more striking is how concentrated the explosion is. The United States, China, and Europe account for 82 percent of global data-center capacity today, and they will capture more than 85 percent of all new additions this decade. In the US in particular, data centers are set to account for almost half of the country's total electricity demand growth between now and 2030, which is an extraordinary and absurd share for one sector. What happened in November underscored just how high the stakes have become. In the same month the IEA issued its warnings, the AI industry saw a global rush of hyperscale announcements. OpenAI and Foxconn unveiled a partnership to build custom AI server hardware at an industrial scale. The kind of cutting-edge racks, cooling systems, and compute modules needed for frontier-model training. SoftBank, meanwhile, announced a plan with Saudi Arabia to develop a massive AI "supercluster," powered in part by the kingdom's abundant solar energy. But everything has its limits. The first limits the world has hit are not in silicon, but in wires, land, and metal. One of the most important warnings in the IEA report concerns the power grid. The world has invested heavily in relatively new generation power sources like renewables, but grid investment has grown at barely half that pace. As the IEA points out, while electricity generation investment has risen by about 70 percent since 2015, grid spending has lagged dramatically. Connection queues for new data centers are now measured in years. In the United States, most developers face delays of one to three years before they can connect to the grid. In Northern Virginia, the world's largest data center hub, the wait can stretch to seven years. Across the Atlantic, parts of the United Kingdom and the European Union face delays of seven to 10 years, and Dublin has stopped accepting new data center connections entirely until 2028. Transforming "digital demand into physical electrons" is becoming increasingly difficult because the grid cannot keep pace. If AI is the new oil, the world is now scrambling to figure out what fuels AI. In the US today, the answer is still natural gas. In 2024, more than 40 percent of the electricity consumed by data centers came from gas, compared to roughly 25 percent from renewables, 20 percent from nuclear, and 15 percent from coal. And unless the country dramatically accelerates renewable and grid expansion, gas will only grow in importance. By 2035, US data-center electricity consumption will more than triple to around 640 terawatt-hours, and natural gas will supply over half that energy. Renewables and nuclear will share most of the rest. The nuclear revival unfolding beneath the surface of the tech world is the most intriguing part of this shift. Tech companies have begun signing long-term electricity deals with nuclear plants, and some power purchase agreements now explicitly reference future capacity from small modular reactors (SMRs) designed to serve data-centre loads. Yet behind all this is a deeper and more uncomfortable question about supply chains. The materials required for AI hardware, especially cutting-edge chips, are dominated by a handful of countries. China controls roughly 95 percent of the world's high-purity silicon, 44 percent of refined copper, and 99 percent of refined gallium, all of which are essential to data-center design, power electronics, and chipmaking. Taiwan dominates advanced-node semiconductor manufacturing. Europe has a near-monopoly on EUV lithography tools, without which advanced chips cannot exist. The United States leads in chip design and hyperscale infrastructure. No one country controls all the pieces, which means everyone is vulnerable. The IEA warns that overlapping dependencies between digital and energy supply chains could pose major security risks as demand for AI accelerates. It is this combination of scarcity, geography, and dependence that makes AI infrastructure feel like the politics of oil. In the 20th century, nations manoeuvred around shipping lanes, wells, refineries, and pipelines. Today, they manoeuvre around server farms, transmission lines, minerals, and compute clusters. Saudi Arabia is now positioning itself as a major host for low-cost solar-powered AI campuses. The United States is becoming the world's largest market for AI electricity demand. China is the indispensable supplier of minerals and manufacturing capacity. Europe is struggling to balance strict climate goals with explosive digital growth. And because crowded cities don't have enough grid capacity, new data centre clusters are being built farther out, reshaping land use and local politics much as earlier oil and gas booms did. The biggest takeaway from the IEA report is that the world is building an AI economy much faster than it understands. Data-center electricity use is set to triple by 2035, but that's still less than 10 percent of the growth in global power demand. On paper, that looks manageable. The problem is where this demand is piling up. Most of it is concentrated in a few clusters in a few countries, pushing their grids to the brink. That's why copper shortages, transformer delays, and long grid queues now regularly appear in AI conversations, something that would have sounded absurd just three years ago. We are entering what the IEA calls the 'Age of Electricity', a world in which nearly half the global economy will depend on electricity as its primary energy input by 2035. We often say "data is the new oil," but that slogan misses the point. The real bottleneck of the AI era is not data, it is energy. Oil powered the machines that shaped the 20th century. Electricity will power the intelligence that shapes the 21st century. And the race to secure that electricity is the race that will quietly determine who gets to build the future.

[3]

How AI can accelerate the energy transition, rather than compete with it

Starting with COP30, collaboration is essential to ensure that AI development accelerates the broader energy transition. The COP30 climate summit in Belém, Brazil is happening at a pivotal moment for the global clean energy transition. But the event has also attracted noticeably limited participation from major players including the US, Russia, India and China, underscoring growing geopolitical and implementation challenges. Now more than ever, the countries gathered for COP30 face pressure to move from ambition to action, advancing the commitments made at COP28 to triple global renewable energy capacity and double energy efficiency by 2030. COP30 has also placed digital technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) firmly on the agenda, recognising AI's energy paradox. While this technology could accelerate clean energy deployment and system optimization, its rapidly rising need for electricity poses new challenges for grids, policy frameworks and long-term planning. This paradox is likely to persist as AI-driven demand surges. Data centre investments are projected to reach around $1.1 trillion by 2029, alongside a global push to scale renewables and upgrade grid infrastructure. AI's growth has created a powerful incentive for technology firms to invest in clean, reliable power. But it also raises a critical question for COP30 negotiators: What if the new clean energy capacity being built remains siloed, powering AI but not strengthening the wider energy systems that communities, industries and households rely on? Stronger coordination between technology leaders, utilities and policy-makers is essential to ensure AI's growth supports, rather than competes with, global decarbonisation goals. Data centres could represent around 3% of global electricity demand in 2030, raising concerns about the ability to support this demand while also meeting global net-zero commitments. AI's rapid expansion has forced technology firms to confront the limits of existing energy systems. Data centres and the advanced chips that drive AI are among the fastest-growing sources of global electricity demand. By 2035, data centres in the US alone could account for 8.6% of total electricity use - more than double their current share. Globally, data centres consumed around 415 TWh in 2024 and this is expected to more than double by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). In response, companies such as Microsoft, Amazon and Google are signing long-term clean-power contracts, investing directly in generation projects and even financing early-stage nuclear and geothermal ventures. These investments could have positive effects, helping to de-risk innovative clean technologies, demonstrate their commercial viability and build local clean energy capacity. However, they also expose a structural tension as AI's clean energy leadership is driven primarily by self-supply imperatives, rather than by system-level planning that delivers shared benefits. Consequently, much of the new capacity being developed may not substantially support the broader electrification of transport, heavy industry or communities. And as tech giants secure long-term renewable deals, smaller players risk being priced out. This could create a two-speed transition that would undermine equitable decarbonisation. Several US utilities, for example, are currently delaying fossil-plant retirements and building new gas facilities to meet surging data-centre demand. If this kind of growth continues, it could strain grid reliability and slow the wider transition to clean power. AI-driven energy investment should be channelled in ways that strengthen entire systems, not just individual data centres. As electricity systems face growing pressures from vehicle and building electrification, reindustrialisation and population-driven demand, the rapid rise of AI introduces an additional layer of complexity. The IEA estimates that data-centre growth could account for more than 20% of total power demand growth in advanced economies through 2030. If most new generation capacity is channelled into powering AI workloads, fewer resources may remain for hard-to-decarbonise sectors, slowing the broader energy transition. At COP30, discussions of "twin transitions" (the convergence of AI and the energy transition) highlight how these forces could work together to drive growth, energy security and climate action. The launch of the AI Climate Institute during COP30 reflects this ambition, positioning AI as a tool for empowerment, particularly for the Global South, where access to clean, affordable energy remains critical. The clean energy capacity powering AI must also reinforce grids and expand energy access to benefit society as a whole. This balance is essential to align technological progress with climate ambition. AI's potential impact on the energy transition could extend well beyond simply consuming electricity. It could serve as a key enabler of system intelligence, improving renewable forecasting, grid balancing and predictive maintenance. AI could also optimise building efficiency and enable flexible demand that adjusts to variable solar and wind output. When applied intentionally, AI could transform the energy system, making it more adaptive, resilient and equitable, rather than simply adding to demand. Achieving this balance will require system-level partnerships across sectors. Based on the latest cross-industry insights from the Forum's AI Energy Impact initiative, four areas for collaboration stand out: Such steps would help ensure that AI's clean energy momentum strengthens public systems, rather than creating parallel energy ecosystems available only to the largest firms. To drive collaborative progress on energy intelligence, future COPs should incorporate several key themes. Dedicated sessions on "AI & clean energy infrastructure" would ensure issues like renewable contract lock-in, equitable access, grid integration and scaling replicable models are formally on the agenda. By amplifying regional case studies such as green data centres, integrated renewable capacity for AI and shared grid access, other countries can learn and replicate these developments. Finally, embedded policy and governance dialogues, covering standards for "green compute" and clean energy for AI data-hubs, would help participants ensure that infrastructure benefits communities, not just hyperscalers. AI's growing electricity demand is both a challenge and an opportunity. It can accelerate the commercialization of clean technologies and reshape energy systems for the better - but only if the benefits extend beyond data centre needs. AI is already driving the next phase of energy innovation. The challenge now is to make sure this innovation strengthens the entire energy system, powering not only the algorithms of the future but also the societies they aim to serve.

[4]

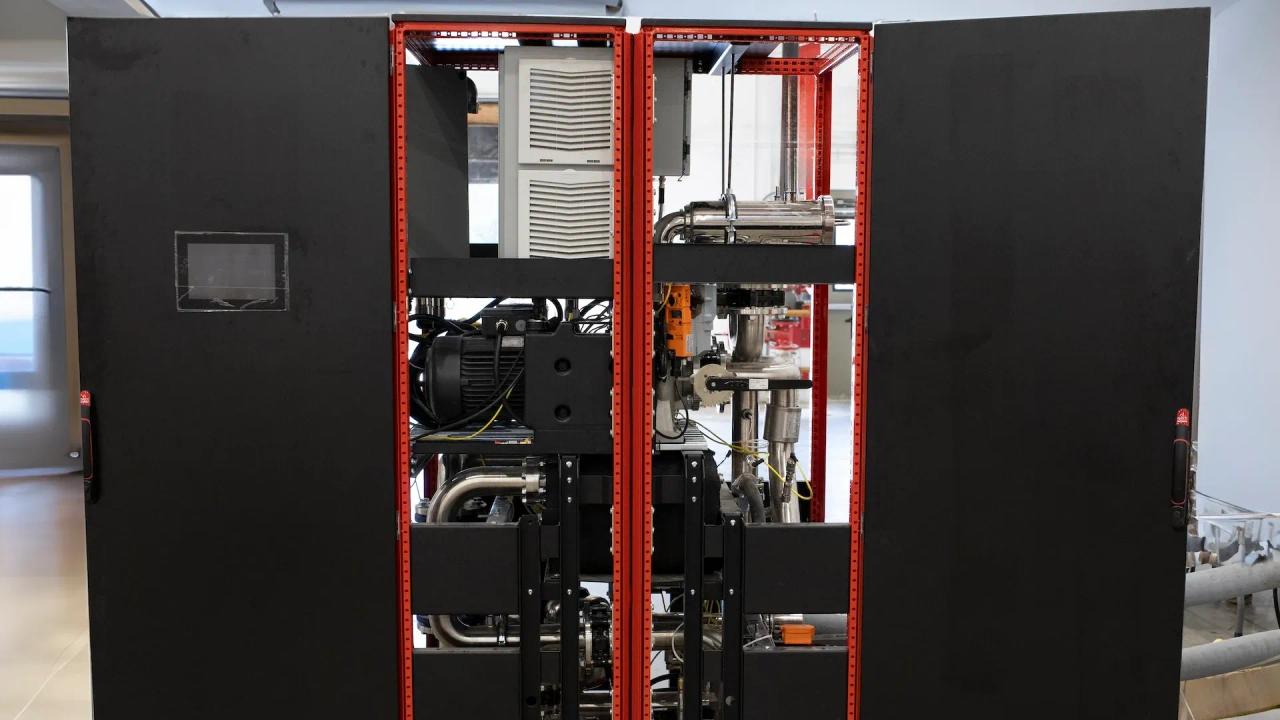

Inventing an electrified future at the intersection of hot and cool

The infrastructure we all rely on is going through a fundamental shift, and electricity demand is at the core. Electrification -- the global trend of more energy systems relying on electricity -- is accelerating. It started with the world moving away from fossil fuels toward cleaner energy, but the AI revolution has changed the direction. The surge in AI computing has spurred a massive build-out of the world's data center infrastructure, vastly increasing the demand for electricity as well as a modernized electrical grid. ELECTRICITY DEMAND ON THE RISE In the U.S. alone, the scale of change is staggering. Estimates put average pre-AI, non-high-performance computing (HPC) data center rack power at about 8 kilowatts per rack. Today, the industry is pushing toward 1 to 3 megawatt racks, an increase of more than 100 times the amount of power. Looking at it another way, in 2023 data centers consumed 4.4% of the total U.S. electricity supply; that percentage is expected to rise to as much as 12% by 2028. Growth in data center power demand is the driving factor behind the need for more electricity, but it is not the only one. The National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) estimates a 9,000% projected growth in power consumption through 2050 to support the use of electric-powered vehicles and similar use cases. Whether driven by data centers or electric vehicles, the bottom line is this: In the next 25 years, we need to add as much electrical infrastructure as was built in the last 100 years. This type of infrastructure investment is almost unprecedented. It is not just the scale of electricity demand that is changing. How we generate electricity is changing, too. Right now, data centers get much of their power through natural gas, but they have recently been revitalizing nuclear energy plans, as that technology has become safer and more reliable. Renewable energy will need to become a larger part of our energy mix as demand for power exceeds that which can be generated through traditional methods. More renewable energy means more demand for energy storage, which helps decouple power production from power use. For example, solar energy is harnessed during the day but stored for use in the evening when demand is at its peak.

[5]

A.I., Data Centers and Climate Impact: How Leaders Are Rewriting the Energy Equation

The environmental footprint of A.I. and data centers is under increasing scrutiny. Concerns over rising electricity demand, water use and the carbon cost of compute now dominate headlines and policy discussions. Yet a deeper, data-driven look reveals a far more nuanced -- and more promising -- story: A.I. and data centers can indeed coexist with climate goals and will, in fact, lead the global march toward meeting them. Sign Up For Our Daily Newsletter Sign Up Thank you for signing up! By clicking submit, you agree to our <a href="http://observermedia.com/terms">terms of service</a> and acknowledge we may use your information to send you emails, product samples, and promotions on this website and other properties. You can opt out anytime. See all of our newsletters A resilient data infrastructure is foundational to modern economic development. Nations that invest in robust data centers and A.I. ecosystems gain the capacity to transition to digital-first economies, which are inherently more efficient and less carbon-intensive. Data centers do not operate in isolation to serve their own needs. Rather, they power the intelligence layer that helps every major industry -- from logistics and manufacturing to healthcare and finance -- operate with greater precision, automation and resource efficiency. In this way, the benefits multiply far beyond the facilities themselves. One of the clearest ways to evaluate greenhouse gas (GHG) performance is to examine how much economic output a nation generates for each ton of emissions released. The International Data Center Authority (IDCA) uses a measure of metric tons of GHG per million U.S. dollars of economic output (or nominal GDP). The global average today sits at 357 tons per million dollars. The United States, home to the world's densest concentration of data centers, operates at roughly half that level. Several E.U. nations, with particularly strong, modern digital infrastructure, perform even better, and the most efficient Nordic economies produce emissions at nearly twice the efficiency of the U.S. By contrast, the least-efficient economies tend to be those dominated by heavy industry or agriculture. China and India, for example, generate more than twice the global average. Many underdeveloped nations across Africa and Asia also produce high emissions relative to their economic output due to limited technological modernization and slower transitions away from carbon-intensive sectors. This is not to say that the United States is an exemplar of best practices in addressing GHGs. It remains below the global average in renewable energy adoption, is heavily reliant on gasoline- and diesel-powered transportation and continues to struggle with a government that oscillates between ambivalence and hostility towards addressing emissions reduction. Moreover, the U.S. and wealthier E.U. nations have outsourced much of their high-emissions manufacturing -- their "dirty work" -- to China, India and less-developed nations, complicating global accounting and underscoring that no country can claim moral high ground. Still, the data highlights an essential point: if the entire world operated at the U.S. level of economic efficiency, global emissions would fall by roughly half. And if the U.S. itself moved closer to the efficiency levels of leading E.U. nations, the reductions would be more significant. Achieving that scale of improvement requires confronting three central questions: How can the world's largest emissions producers work together to address reductions across heavy industry? China, the U.S., India and Russia, along with industrial powerhouses like Japan, South Korea and major petrostates, must work in coordination to decarbonize heavy industry. A.I. can be a powerful lever here, optimizing automated manufacturing, refining supply chains and enabling predictive efficiency improvements at scale. Equally important is accelerating the shift toward low-carbon construction materials, particularly alternatives to cement and steel, which account for roughly 15 percent of global GHG emissions. How can developing nations build their digital economies with minimal climate impact? Developing nations are the subject of many discussions at COP30, the annual United Nations meeting focused on climate change abatement, this year held in Belém, Brazil. Most use only 2 to 5 percent of the electricity consumed per person in the developed economies, and their data center infrastructure remains even less mature than their electricity grids. IDCA's research shows a strong correlation between digital infrastructure and socioeconomic advancement, making sustainable grid development and low-carbon construction paramount. These countries have a narrow but critical opportunity to build modern digital economies without inheriting the emissions burdens of previous industrial revolutions. How can the next generation of massive A.I. centers being planned and built today prioritize emissions reduction? As thousands of new A.I. facilities are planned and constructed worldwide, their environmental profiles will continue to transform the global economy into a digital economy. These centers must be designed for maximum efficiency, powered by increasingly clean grids and built with clear sustainability criteria. But their impact won't end at their footprint. Strong A.I. backbones can accelerate global decarbonization by enabling smarter transportation networks, optimizing energy systems, transforming healthcare analytics, advancing meteorological modeling and empowering scientific discovery across environmental domains. If world leaders, business executives and citizens collectively demand that A.I. and data centers be aimed at humanity's most pressing scientific and environmental challenges, then A.I. centers will be understood not as climate liabilities, but as essential climate tools. The path forward will not be simple, but it is one that we are fully capable of navigating. Mehdi Paryavi is the founder and CEO of the International Data Center Authority (IDCA), the world's leading Digital Economy think tank.

Share

Share

Copy Link

As AI drives unprecedented electricity demand through data center expansion, the technology sector is simultaneously becoming a major force in clean energy investment, creating both challenges and opportunities for the global energy transition.

The New Energy War: Data Centers Eclipse Oil

The global energy landscape is undergoing a fundamental transformation as artificial intelligence reshapes power demand patterns worldwide. According to the International Energy Agency's November 2025 World Energy Outlook, the world will spend $580 billion on data centers in 2025—$40 billion more than total global spending on new oil supplies

2

. This unprecedented shift marks the end of oil's dominance in energy investment and signals the beginning of what experts are calling the "energy war of the 21st century."

Source: Observer

The scale of this transformation is staggering. In the United States alone, average data center rack power has jumped from 8 kilowatts to 1-3 megawatts—more than a 100-fold increase

4

. Data centers consumed 4.4% of total U.S. electricity supply in 2023, with projections reaching as high as 12% by 2028.AI's Exponential Power Appetite

Electricity consumption from AI servers alone will increase fivefold by 2030, contributing to a doubling of total data center electricity demand worldwide

2

. This growth is highly concentrated, with the United States, China, and Europe accounting for 82% of global data center capacity today and capturing more than 85% of all new additions this decade.

Source: Fast Company

The infrastructure challenges are becoming apparent across major markets. In the United States, most developers face delays of one to three years before connecting to the grid, while Northern Virginia—the world's largest data center hub—sees wait times stretching to seven years

2

. Dublin has stopped accepting new data center connections entirely until 2028, highlighting the strain on existing grid infrastructure.The Clean Energy Paradox

While AI's energy demands pose significant challenges, the technology is simultaneously driving unprecedented investment in clean energy infrastructure. Tech giants including Microsoft, Amazon, and Google are signing long-term clean-power contracts, investing directly in generation projects, and financing early-stage nuclear and geothermal ventures

3

.This creates what researchers call AI's "energy paradox"—while the technology accelerates clean energy deployment and system optimization, its rapidly rising electricity needs pose new challenges for grids and long-term planning

3

. Data center investments are projected to reach $1.1 trillion by 2029, alongside a global push to scale renewables and upgrade grid infrastructure.Grid Optimization and Smart Management

AI is proving instrumental in managing the complexity of modern electrical grids. As MIT's Anuradha Annaswamy explains, "you need to introduce a whole information infrastructure to supplement and complement the physical infrastructure"

1

. AI algorithms help forecast which plants should run while ensuring proper frequency, voltage, and power characteristics for grid operation.

Source: MIT

The technology enables new approaches to supply and demand management. Electric vehicle batteries can serve as grid power sources when needed, while smart thermostats and flexible data center operations can reduce demand during peak periods

1

. AI also enables predictive maintenance, alerting operators to potential equipment failures before they cause costly downtime or blackouts.Related Stories

Global Climate Implications

The relationship between AI development and climate goals remains complex. Data centers could represent around 3% of global electricity demand by 2030, raising concerns about supporting this demand while meeting net-zero commitments

3

. However, analysis by the International Data Center Authority shows that nations with robust digital infrastructure tend to generate more economic output per ton of emissions.The United States, despite hosting the world's densest concentration of data centers, operates at roughly half the global average of 357 tons of greenhouse gas per million dollars of economic output

5

. Several European Union nations with strong digital infrastructure perform even better, suggesting that AI-driven economic efficiency can coexist with climate goals.The Nuclear Renaissance

The nuclear revival unfolding within the tech sector represents one of the most significant developments in energy policy. Tech companies are signing long-term electricity deals with nuclear plants, with some power purchase agreements explicitly referencing future capacity from small modular reactors designed to serve data center loads

2

.Currently, U.S. data centers derive more than 40% of their electricity from natural gas, compared to roughly 25% from renewables, 20% from nuclear, and 15% from coal

2

. By 2035, natural gas is projected to supply over half of the tripled data center electricity consumption unless renewable and grid expansion dramatically accelerates.References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Pentagon's Anthropic showdown exposes who controls AI guardrails in military contracts

Policy and Regulation

3

Anthropic challenges Pentagon supply chain risk label in court over AI usage restrictions

Policy and Regulation