AI Co-Pilot for Bionic Hands Transforms How Amputees Control Prosthetics with Intuitive Grasping

4 Sources

4 Sources

[1]

Scientists built an AI co-pilot for prosthetic bionic hands

Modern bionic hand prostheses nearly match their natural counterparts when it comes to dexterity, degrees of freedom, and capability. And many amputees who tried advanced bionic hands apparently didn't like them. "Up to 50 percent of people with upper limb amputation abandon these prostheses, never to use them again," says Jake George, an electrical and computer engineer at the University of Utah. The main issue with bionic hands that drives users away from them, George explains, is that they're difficult to control. "Our goal was making such bionic arms more intuitive, so that users could go about their tasks without having to think about it," George says. To make this happen, his team came up with an AI bionic hand co-pilot. Micro-management issues Bionic hands' control problems stem largely from their lack of autonomy. Grasping a paper cup without crushing it or catching a ball mid-flight appear so effortless because our natural movements rely on an elaborate system of reflexes and feedback loops. When an object you hold begins to slip, tiny mechanoreceptors in your fingertips send signals to the nervous system that make the hand tighten its grip. This all happens within 60 to 80 milliseconds -- before you even consciously notice. This reflex is just one of many ways your brain automatically assists you in dexterity-based tasks. Most commercially available bionic hands do not have that built-in autonomic reflex -- everything must be controlled by the user, which makes them extremely involved to use. To get an idea of how hard this is, you'd need to imagine trying to think about precisely adjusting the position of 27 major joints and choosing the appropriate force to apply with each of the 20 muscles present in a natural hand. It doesn't help that the bandwidth of the interface between the bionic hand and the user is often limited. In most cases, users controlled bionic hands via an app where they could choose predetermined grip types and adjust forces applied by various actuators. A slightly more natural alternative is electromyography, where electric signals from the remaining muscles are in commands the bionic hand followed. But this too was far from perfect. "To grasp the object, you have to reach towards it, flex the muscles, and then effectively sit there and concentrate on holding your muscles in the exact same position to maintain the same grasp," explains Marshall Trout, a University of Utah researcher and lead author of the study. To build their "intuitive" bionic hand, George, Trout, and their colleagues started by fitting it with custom sensors. Feeling the grip The researchers started their work with taking one of the commercially available bionic hands and replacing its fingertips with silicone-wrapped pressure and proximity sensors. This allowed the hand to detect when it was getting close to an object and precisely measure the force required to hold it without crushing it or letting it slip. To process the data gathered by the sensors, the team built an AI controller that moved the joints and adjusted the force of the grip. "We had the hand still and moved it back and forth so that the fingertips would touch the object and then we backed away," Tout says. By repeating those back-and-forth movements countless times, the team collected enough training data to have the AI recognize various objects and switch between different grip types. The AI also controlled each finger individually. "This way we achieved natural grasping patterns," George explains. "When you put an object in front of the hand it will naturally conform and each finger will do its own thing." Assisted driving While this kind of autonomous gripping was demonstrated before, the brand-new touch the team applied was deciding what was in charge of the system. Earlier research projects that investigated autonomous prostheses relied on the user switching the autonomy on and off. By contrast, George and Trout's approach focused on shared control. "It's a subtle way the machine is helping. It's not a self-driving car that drives you on its own and it's not like an assistant that pulls you back into the lane when you turn the steering wheel without an indicator turned on," George says. Instead, the system quietly works behind the scenes without it feeling like it's fighting the user or taking over. The user remained in charge at all times and can tighten or loosen the grip, or release the object to let it drop. To test their AI-powered hand, the team asked intact and amputee participants to manipulate fragile objects: pick up a paper cup and drink from it, or take an egg from a plate and put it down somewhere else. Without the AI, they could succeed roughly one or two times in 10 attempts. With the AI assistant turned on, their success rate jumped to 80 or 90 percent. The AI also decreased the participants' cognitive burden, meaning they had to focus less on making the hand work. But we're still a long way away from seamlessly integrating machines with the human body. Into the wild "The next step is to really take this system into the real world and have someone use it in their home setting," Trout says. So far, the performance of the AI bionic hand was assessed under controlled laboratory conditions, working with settings and objects the team specifically chose or designed. "I want to make a caveat here that this hand is not as dexterous or easy to control as a natural, intact limb," George cautions. He thinks that every little increment that we make in prosthetics is allowing amputees to do more tasks in their daily life. Still, to get to the Star Wars or Cyberpunk technology level where bionic prostheses are just as good or better than natural limbs, we're going to need more than just incremental changes. Trout says we're almost there as far as robotics go. "These prostheses are really dexterous, with high degrees of freedom," Trout says, "but there's no good way to control them." This in part comes down to the challenge of getting the information in and out of users themselves. "Skin surface electromyography is very noisy, so improving this interface with things like internal electromyography or using neural implants can really improve the algorithms we already have," Trout argued. This is why the team is currently working on neural interface technologies and looking for industry partners. "The goal is to combine all these approaches in one device," George says. "We want to build an AI-powered robotic hand with a neural interface working with a company that would take it to the market in larger clinical trials." Nature Communications, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65965-9

[2]

AI-Powered Bionic Hand Restores Natural, Intuitive Grasping Ability - Neuroscience News

Summary: A new study shows that integrating artificial intelligence with advanced proximity and pressure sensors allows a commercial bionic hand to grasp objects in a natural, intuitive way -- reducing cognitive effort for amputees. By training an artificial neural network on grasping postures, each finger could independently "see" objects and automatically move into the correct position, improving grip security and precision. Participants performed everyday tasks such as lifting cups and picking up small items with far less mental strain and without extensive training. The shared-control system balanced human intent with machine assistance, enabling effortless, lifelike use of a prosthetic hand. Whether you're reaching for a mug, a pencil or someone's hand, you don't need to consciously instruct each of your fingers on where they need to go to get a proper grip. The loss of that intrinsic ability is one of the many challenges people with prosthetic arms and hands face. Even with the most advanced robotic prostheses, these everyday activities come with an added cognitive burden as users purposefully open and close their fingers around a target. Researchers at the University of Utah are now using artificial intelligence to solve this problem. By integrating proximity and pressure sensors into a commercial bionic hand, and then training an artificial neural network on grasping postures, the researchers developed an autonomous approach that is more like the natural, intuitive way we grip objects. When working in tandem with the artificial intelligence, study participants demonstrated greater grip security, greater grip precision and less mental effort. Critically, the participants were able to perform numerous everyday tasks, such as picking up small objects and raising a cup, using different gripping styles, all without extensive training or practice. The study was led by engineering professor Jacob A. George and Marshall Trout, a postdoctoral researcher in the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab, and appears Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications. "As lifelike as bionic arms are becoming, controlling them is still not easy or intuitive," Trout said. "Nearly half of all users will abandon their prosthesis, often citing their poor controls and cognitive burden." One problem is that most commercial bionic arms and hands have no way of replicating the sense of touch that normally gives us intuitive, reflexive ways of grasping objects. Dexterity is not simply a matter of sensory feedback, however. We also have subconscious models in our brains that simulate and anticipate hand-object interactions; a "smart" hand would also need to learn these automatic responses over time. The Utah researchers addressed the first problem by outfitting an artificial hand, manufactured by TASKA Prosthetics, with custom fingertips. In addition to detecting pressure, these fingertips were equipped with optical proximity sensors designed to replicate the finest sense of touch. The fingers could detect an effectively weightless cotton ball being dropped on them, for example. For the second problem, they trained an artificial neural network model on the proximity data so that the fingers would naturally move to the exact distance necessary to form a perfect grasp of the object. Because each finger has its own sensor and can "see" in front of it, each digit works in parallel to form a perfect, stable grasp across any object. But one problem still remained. What if the user didn't intend to grasp the object in that exact manner? What if, for example, they wanted to open their hand to drop the object? To address this final piece of the puzzle, the researchers created a bioinspired approach that involves sharing control between the user and the AI agent. The success of the approach relied on finding the right balance between human and machine control. "What we don't want is the user fighting the machine for control. In contrast, here the machine improved the precision of the user while also making the tasks easier," Trout said. "In essence, the machine augmented their natural control so that they could complete tasks without having to think about them." The researchers also conducted studies with four participants whose amputations fall between the elbow and wrist. In addition to improved performance on standardized tasks, they also attempted multiple everyday activities that required fine motor control. Simple tasks, like drinking from a plastic cup, can be incredibly difficult for an amputee; squeeze too soft and you'll drop it, but squeeze too hard and you'll break it. "By adding some artificial intelligence, we were able to offload this aspect of grasping to the prosthesis itself," George said. "The end result is more intuitive and more dexterous control, which allows simple tasks to be simple again." George is the Solzbacher-Chen Endowed Professor in the John and Marcia Price College of Engineering's Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering and the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine's Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. This work is part of the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab's larger vision to improve the quality of life for amputees. "The study team is also exploring implanted neural interfaces that allow individuals to control prostheses with their mind and even get a sense of touch coming back from this," George said. "Next steps, the team plans to blend these technologies, so that their enhanced sensors can improve tactile function and the intelligent prosthesis can blend seamlessly with thought-based control." The study was published online Dec.9 in Nature Communications under the title "Shared human-machine control of an intelligent bionic hand improves grasping and decreases cognitive burden for transradial amputees." Coauthors include NeuroRobotics Lab members Fredi Mino, Connor Olsen and Taylor Hansen, as well as Masaru Teramoto, research assistant professor in the School of Medicine's Division of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, David Warren, research associate professor emeritus in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, and Jacob Segil of the University of Colorado Boulder. Funding: Funding came from the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation. Author: Evan Lerner Source: University of Utah Contact: Evan Lerner - University of Utah Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News Original Research: Open access. "Shared human-machine control of an intelligent bionic hand improves grasping and decreases cognitive burden for transradial amputees" by Jacob A. George et al. Nature Communications Abstract Shared human-machine control of an intelligent bionic hand improves grasping and decreases cognitive burden for transradial amputees Bionic hands can replicate many movements of the human hand, but our ability to intuitively control these bionic hands is limited. Humans' manual dexterity is partly due to control loops driven by sensory feedback. Here, we describe the integration of proximity and pressure sensors into a commercial prosthesis to enable autonomous grasping and show that continuously sharing control between the autonomous hand and the user improves dexterity and user experience. Artificial intelligence moved each finger to the point of contact while the user controlled the grasp with surface electromyography. A bioinspired dynamically weighted sum merged machine and user intent. Shared control resulted in greater grip security, greater grip precision, and less cognitive burden. Demonstrations include intact and amputee participants using the modified prosthesis to perform real-world tasks with different grip patterns. Thus, granting some autonomy to bionic hands presents a translatable and generalizable approach towards more dexterous and intuitive control.

[3]

Watch: AI makes using a bionic hand way easier

Researchers are using AI to finetune a robotic prosthesis to improve manual dexterity by finding right balance between human and machine control. Whether you're reaching for a mug, a pencil, or someone's hand, you don't need to consciously instruct each of your fingers on where they need to go to get a proper grip. The loss of that intrinsic ability is one of the many challenges people with prosthetic arms and hands face. Even with the most advanced robotic prostheses, these everyday activities come with an added cognitive burden as users purposefully open and close their fingers around a target. Researchers at the University of Utah are now using artificial intelligence to solve this problem. By integrating proximity and pressure sensors into a commercial bionic hand and then training an artificial neural network on grasping postures, the researchers developed an autonomous approach that is more like the natural, intuitive way we grip objects. When working in tandem with the artificial intelligence, study participants demonstrated greater grip security, greater grip precision, and less mental effort. Critically, the participants were able to perform numerous everyday tasks, such as picking up small objects and raising a cup, using different gripping styles, all without extensive training or practice. The study was led by engineering professor Jacob A. George and Marshall Trout, a postdoctoral researcher in the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab, and appears in the journal Nature Communications. "As lifelike as bionic arms are becoming, controlling them is still not easy or intuitive," Trout says. "Nearly half of all users will abandon their prosthesis, often citing their poor controls and cognitive burden." One problem is that most commercial bionic arms and hands have no way of replicating the sense of touch that normally gives us intuitive, reflexive ways of grasping objects. Dexterity is not simply a matter of sensory feedback, however. We also have subconscious models in our brains that simulate and anticipate hand-object interactions; a "smart" hand would also need to learn these automatic responses over time. The Utah researchers addressed the first problem by outfitting an artificial hand, manufactured by TASKA Prosthetics, with custom fingertips. In addition to detecting pressure, these fingertips were equipped with optical proximity sensors designed to replicate the finest sense of touch. The fingers could detect an effectively weightless cotton ball being dropped on them, for example. For the second problem, they trained an artificial neural network model on the proximity data so that the fingers would naturally move to the exact distance necessary to form a perfect grasp of the object. Because each finger has its own sensor and can "see" in front of it, each digit works in parallel to form a perfect, stable grasp across any object. But one problem still remained. What if the user didn't intend to grasp the object in that exact manner? What if, for example, they wanted to open their hand to drop the object? To address this final piece of the puzzle, the researchers created a bioinspired approach that involves sharing control between the user and the AI agent. The success of the approach relied on finding the right balance between human and machine control. "What we don't want is the user fighting the machine for control. In contrast, here the machine improved the precision of the user while also making the tasks easier," Trout says. "In essence, the machine augmented their natural control so that they could complete tasks without having to think about them." The researchers also conducted studies with four participants whose amputations fell between the elbow and wrist. In addition to improved performance on standardized tasks, they also attempted multiple everyday activities that required fine motor control. Simple tasks, like drinking from a plastic cup, can be incredibly difficult for an amputee; squeeze too soft and you'll drop it, but squeeze too hard and you'll break it. "By adding some artificial intelligence, we were able to offload this aspect of grasping to the prosthesis itself," George says. "The end result is more intuitive and more dexterous control, which allows simple tasks to be simple again." "The study team is also exploring implanted neural interfaces that allow individuals to control prostheses with their mind and even get a sense of touch coming back from this," George says. "Next steps, the team plans to blend these technologies, so that their enhanced sensors can improve tactile function and the intelligent prosthesis can blend seamlessly with thought-based control." Additional coauthors are from the University of Utah and the University of Colorado, Boulder Funding came from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

[4]

Amputees often feel disconnected from their bionic hands. AI could bridge the gap

Researchers have built a prosthetic hand that, with the help of artificial intelligence, can act a lot more like a natural one. The key is to have the hand recognize when the user wants to do something, then share control of the motions needed to complete the task. The approach, which combined AI with special sensors, helped four people missing a hand simulate drinking from a cup, says Marshall Trout, a researcher at the University of Utah and the study's lead author. When the sensors and AI were helping, the participants could "very reliably" grasp a cup and pretend to take a sip, Trout says. But without this shared control of the bionic hand, he says, they "crushed it or dropped it every single time." The success, described in the journal Nature Communications, is notable because "the ability to exert grasp force is one of the things we really struggle with in prosthetics right now," says John Downey, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the research. Problems like that cause many amputees to grow frustrated with their bionic hands and stop using them, he says. The latest bionic hands have motors that allow them to swivel, move individual fingers, and manipulate objects. They can also detect electrical signals coming from the muscles that are used to control those actions. But as bionic hands have become more capable, they have also become more difficult for users to control, Trout says. "The person has to sit there and really focus on what they're doing," he says, "which is really not how an intact hand behaves." A natural hand, for example, requires very little cognitive effort to carry out routine tasks like reaching for an object or tying a shoelace. That's because once a person puts the task in motion, most of the work is done by specialized circuits in the brain and spine that take over. These circuits allow many tasks to be accomplished efficiently and automatically. Our conscious mind only intervenes if, say, a shoelace breaks, or an object is moved unexpectedly. So Trout and a team of scientists set out to make a smart prosthetic that would act more like a person's own hand. "I just know where my coffee cup is, and my hand will just naturally squeeze and make contact with it," he says. "That's what we wanted to recreate with this system." The team turned to AI to take on some of these subconscious functions. This meant detecting not just the signal coming from a muscle, but the intention behind it. For example, the AI control system learned to detect the tiniest twitch in a muscle that flexes the hand. "That's when the machine controller kicks on, saying, 'Oh, I'm trying to grasp something, I'm not just sitting still,'" Trout says. To make the approach work, the scientists modified a bionic hand by adding proximity and pressure sensors. That allows the AI system to gauge the distance to an object and assess its shape. Meanwhile, the pressure sensors on the fingertips tell the user how firmly their prosthetic hand is holding the object. The idea of sharing control of a bionic hand addresses a reaction many people have when they use a prosthetic with superhuman abilities, says Jacob George, a professor at the University of Utah and director of the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab. "You can make a robotic hand that can do tasks better than a human user," he says. "But when you actually give that to someone, they don't like it." That's because the device feels foreign and out of their control, he says. John Downey says that one reason we feel connected to our own hands is that they are controlled jointly by our thoughts and by reflexes in the brain stem and spinal cord. That means the thinking part of our brain doesn't have to worry about the details of every motion. "All of our motor control involves reflexes that are subconscious," Downey says, "so providing robotic imitations of those reflex loops is going to be important." George says the smart bionic hand solves for that issue. "The machine is doing something and the human is doing something, and we're combining those two together," he says. That's a critical step toward creating prosthetic limbs that feel like an extension of the person's own body. "Ultimately, when you create an embodied robotic hand, it becomes a part of that user's experience, it becomes a part of themselves and not just a tool," George says. Even the most advanced bionic hands still need some help from a human brain, Downey says. For example, a person can use the same natural hand to gently thread a needle, then firmly lift up a child. "The dynamic range on that is far beyond what robots typically handle," Downey says. That is likely to change, as bionic limbs become increasingly versatile and capable. What won't change, scientists say, is humans' desire to retain a sense of control over their artificial appendages.

Share

Share

Copy Link

University of Utah researchers developed an AI co-pilot for bionic hands that dramatically improves control for amputees. The system uses proximity and pressure sensors combined with artificial intelligence to enable natural, intuitive grasping. Success rates jumped from 10-20% to 80-90% in tests involving fragile objects, while significantly reducing the cognitive burden on users.

AI Co-Pilot Addresses Critical Control Problem in Bionic Hands

Up to 50 percent of amputees abandon advanced bionic hands, citing poor controls and excessive cognitive burden as primary reasons for discontinuation

1

. Researchers at the University of Utah have developed an AI co-pilot system that fundamentally changes how amputees interact with prosthetic limbs. Led by engineering professor Jacob A. George and postdoctoral researcher Marshall Trout from the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab, the team published their findings in Nature Communications2

.

Source: Futurity

The challenge stems from a lack of autonomy in current prosthetic designs. Natural hands rely on elaborate reflexes and feedback loops that operate within 60 to 80 milliseconds, before conscious awareness even registers

1

. Controlling a natural hand involves managing 27 major joints and 20 muscles simultaneously, yet this happens effortlessly through subconscious brain circuits. Most commercially available bionic hands lack these automatic responses, forcing users to micromanage every movement through apps or surface electromyography signals from remaining muscles.Proximity and Pressure Sensors Enable Natural Grasping Ability

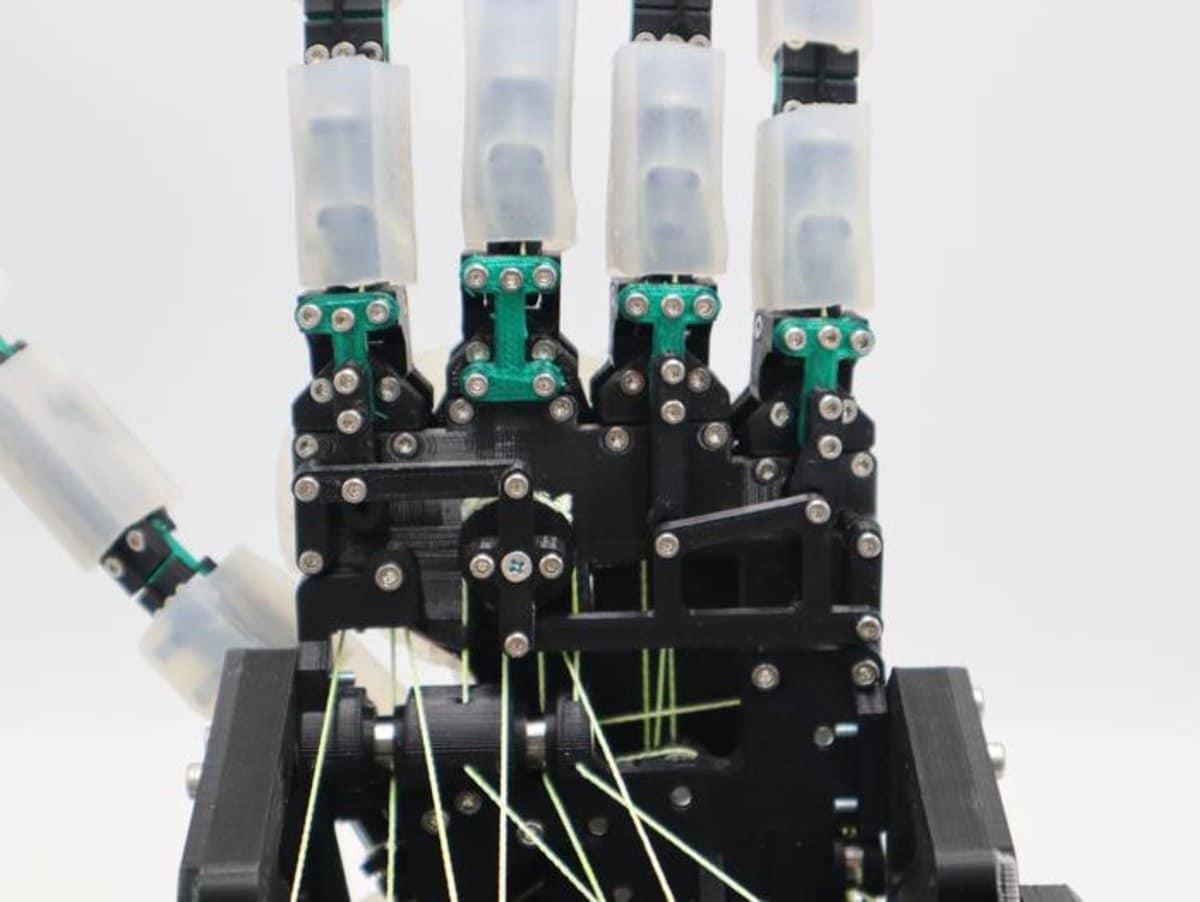

The research team modified a commercial bionic hand manufactured by TASKA Prosthetics by replacing fingertips with silicone-wrapped proximity and pressure sensors

1

. These optical proximity sensors can detect objects approaching and measure the precise grasp force needed to hold items without crushing or dropping them. The sensors proved sensitive enough to detect an effectively weightless cotton ball being dropped on the fingertips3

.

Source: Neuroscience News

The team trained an artificial neural network by repeatedly moving the hand back and forth to touch objects, collecting extensive training data on various grip patterns

1

. Because each finger has its own sensor and can "see" in front of it, each digit works in parallel to form a stable grasp across any object2

. This approach enables the AI to recognize different objects and switch between grip types while controlling each finger independently, achieving natural conforming movements.Shared Control System Balances Human-Machine Control

The breakthrough lies in how control is distributed between user and machine. Earlier autonomous prostheses required users to manually switch autonomy on and off, creating an awkward experience

1

. The University of Utah team implemented a bioinspired approach involving shared control that operates subtly in the background. "What we don't want is the user fighting the machine for control. In contrast, here the machine improved the precision of the user while also making the tasks easier," Trout explained2

.The AI detects the tiniest muscle twitch that flexes the hand, interpreting this as intention to grasp. "That's when the machine controller kicks on, saying, 'Oh, I'm trying to grasp something, I'm not just sitting still,'" Trout noted

4

. Users remain in charge at all times and can adjust grip strength or release objects at will. This balance creates what George describes as an embodied experience where the prosthetic becomes part of the user's sense of self rather than just a tool4

.Related Stories

Testing Shows Dramatic Improvement in Dexterity and Reduces Cognitive Burden

The research team conducted studies with four participants whose amputations fell between the elbow and wrist. They performed everyday tasks requiring fine motor control, such as picking up a paper cup to drink from it or transferring an egg from a plate without breaking it

1

. Without artificial intelligence assistance, participants succeeded in only one or two attempts out of 10. With the AI system activated, success rates jumped to 80 or 90 percent1

.Participants demonstrated greater grip security, greater grip precision, and less mental effort when working with the intelligent system

2

. Critically, they accomplished these improvements without extensive training or practice, using different gripping styles for various objects3

. Simple tasks like drinking from a plastic cup, which requires precise grasp force to avoid crushing or dropping, became manageable again. "By adding some artificial intelligence, we were able to offload this aspect of grasping to the prosthesis itself," George said2

.

Source: Ars Technica

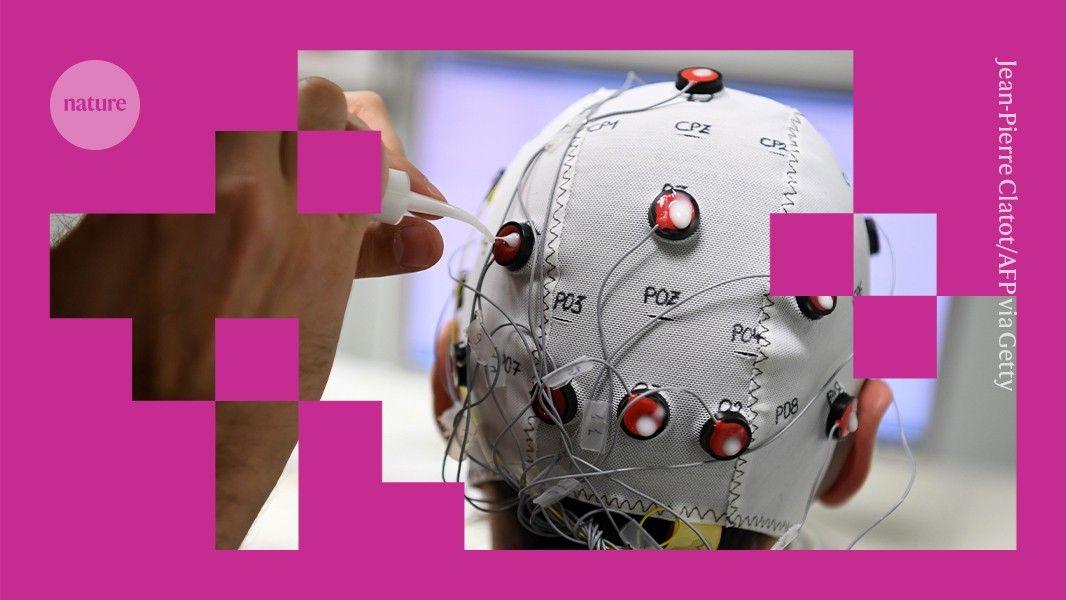

Future Integration with Neural Interfaces and Tactile Feedback

The team is exploring implanted neural interfaces that would allow individuals to control prostheses with their thoughts while receiving tactile feedback

3

. Next steps involve blending these technologies so enhanced sensors can improve tactile function while the intelligent prosthesis integrates seamlessly with thought-based control. John Downey, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago not involved in the research, notes that providing robotic imitations of subconscious reflex loops will be important as the field advances4

.The dynamic range required for human tasks—from gently threading a needle to firmly lifting a child—remains a challenge for robotics

4

. As advanced bionic hands become increasingly versatile and capable, the research suggests that maintaining human control while augmenting it with machine intelligence offers the most promising path forward. The work received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation3

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[2]

[3]

Related Stories

AI-Enhanced Brain-Computer Interface Boosts Performance for Paralyzed Users

02 Sept 2025•Technology

Breakthrough: AI-Powered Brain Implant Enables Paralyzed Man to Control Robotic Arm for Record 7 Months

07 Mar 2025•Science and Research

AI Prosthetic Arm Study Finds One-Second Movement Speed Feels Most Natural to Users

13 Feb 2026•Science and Research

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic takes Pentagon to court over unprecedented supply chain risk designation

Policy and Regulation

3

Meta smart glasses face lawsuit and UK probe after workers watched intimate user footage

Policy and Regulation