AI agents trigger $1 trillion software selloff as enterprise giants face existential threat

9 Sources

9 Sources

[1]

AI threatens to eat business software - and it could change the way we work

In recent weeks, a range of large "software-as-a-service" companies, including Salesforce, ServiceNow and Oracle, have seen their share prices tumble. Even if you've never used these companies' software tools, there's a good chance your employer has. These tools manage key data about customers, employees, suppliers and products, supporting everything from payroll and purchasing to customer service. Now new "agentic" artificial intelligence (AI) tools for business are expected to reduce reliance on traditional software for everyday work. These include Anthropic's Cowork, OpenAI's Frontier and open-source agent platforms such as OpenClaw. But just how important are these software-as-a-service companies now? How fast could AI replace them - and are the jobs of people who use the software safe? The digital plumbing of the business world Software‑as‑a‑service systems run in the cloud, reducing the need for in‑house hardware and IT staff. They also make it easier for businesses to scale as they grow. Software-as-a-service vendors get a steady, recurring income as firms "rent" the software, usually paying per user (often called a "seat"). And because these systems become deeply embedded in how these firms operate, switching providers can be costly and risky. Sometimes firms are locked into using them for a decade or more. Digital co-workers Agentic AI systems act like digital co-workers or "bots". Software bots or agents are not new. Robotic process automation is used in many firms to handle routine, rules-based tasks. The more recent developments in agentic AI combine this automation with generative AI technology, to complete more complex goals. This can include selecting tools, making decisions and completing multi-step tasks. These agents can replace human effort in everything from handling expense reports to managing social media and customer correspondence. What AI can now do Recent advances, however, are even more ambitious. These tools are reportedly now writing usable software code. Soaring productivity in software development has been attributed to the use of AI agents like Anthropic's "Claude Code". Anthropic's Cowork tool extends this from coding to other knowledge work tasks. In principle, a user describes a business problem in plain language. Then agentic AI delivers a code solution that works with existing organisational systems. If this becomes reliable, AI agents will resemble junior software engineers and process designers. AI agents like Cowork expand this to other entry-level work. These advances are what recently spooked the market (though many affected stocks have since recovered slightly). How much of this fall is a temporary overreaction versus a real long-term shift, time will tell. How will it affect jobs and costs? Since the arrival of OpenAI's ChatGPT in November 2022, AI tools have raised deep questions about the future of work. Some predict many white-collar roles, including those of software engineers and lawyers, will be transformed or even replaced. Agentic AI appears to accelerate this trend. It promises to let many knowledge workers build workflows and tools without knowing how to code. Software-as-a-service providers will also feel pressure to change their pricing models. The traditional model of charging per human user may make less sense when much of the work is done by AI agents. Vendors may have to move to pricing based on actual usage or value created. Hype, reality and limits Several forces are likely to moderate or limit the pace of change. First, the promised potential of AI has not yet been fully realised. For some tasks, using AI can even worsen performance. The biggest gains are still likely to be in routine work that can be readily automated, not work that requires complex judgement. Where AI replaces, rather than augments, human labour is where work practices will change the most. The nearly 20% decline in junior software engineering jobs over three years highlights the effects of AI automation. As AI agents improve at higher-level reasoning, more senior roles will similarly be threatened. Second, to benefit from AI, firms must invest in redesigning jobs, processes and control systems. We've long known that organisational change is slower and messier than technology change. Third, we have to consider risks and regulation. Heavy reliance on AI can erode human knowledge and skills. Short-term efficiency gains could be offset by long-term loss of expertise and creativity. Ironically, the loss of knowledge and expertise could make it harder for companies to assure AI systems comply with company policies and government regulations. The checks and balances that help an organisation run safely and honestly do not disappear when AI arrives. In many ways, they become more complex. Technology is evolving quickly What is clear is that significant change is already under way. Technology is evolving quickly. Work practices and business models are starting to adjust. Laws and social norms will change more slowly. Software companies won't disappear overnight, and neither will the jobs of people using that software. But agentic AI will change what they sell, how they charge and how visible they are to end users.

[2]

Fund Beating 99% of Peers Sees Few Software Firms Surviving AI

Selling software stocks before the crowd paid off for Nick Evans, a Polar Capital fund manager. His warning to potential bargain hunters: most shares are still toxic and few firms will survive. "We think application software faces an existential threat from AI," said Evans, whose $12 billion global technology fund beat 99% of peers over one year and 97% over five. Fears that sophisticated AI tools like Anthropic PBC's Claude Cowork will disrupt software businesses sent their stocks tumbling this year. An exchange-traded fund tracking the US software sector is down 22%, a sharp contrast to semiconductor stocks that have soared as AI spurs computing demand. Get the Bloomberg Deals newsletter. Get the Bloomberg Deals newsletter. Get the Bloomberg Deals newsletter. The latest news and analysis on M&A, IPOs, private equity, startup investing and the dealmakers behind it all, for subscribers only. The latest news and analysis on M&A, IPOs, private equity, startup investing and the dealmakers behind it all, for subscribers only. The latest news and analysis on M&A, IPOs, private equity, startup investing and the dealmakers behind it all, for subscribers only. Bloomberg may send me offers and promotions. Plus Signed UpPlus Sign UpPlus Sign Up By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service. Application software, which helps users perform tasks such as writing documents and managing payrolls, looks particularly at risk, according to Evans. Apart from a small position and some call options in Microsoft Corp., the fund manager has sold all other holdings in the sector, including SAP SE, ServiceNow Inc., Adobe Inc. and HubSpot Inc. "We won't go back to these companies," he said in an interview. In his view, AI coding tools have improved so much that they can already replicate and modify much existing software. That means established firms now face much greater competition from their own clients, who are racing to develop new tools internally to cut costs, as well as AI startups. Companies such as SAP that make complex software packages will likely be more resilient, according to Evans. But with AI tools "getting dramatically more powerful," there is considerable uncertainty about their long-term valuations, he said. Seven out of the top 10 positions of the fund as of end-January were semiconductor companies, including top holding Nvidia Corp. that occupied nearly 10% of the portfolio. Aside from chipmakers, Evans said he's bullish on firms that make networking gears, fiber optics, and those that provide power and energy infrastructure to data centers. Squeeze on cashflow The market rout triggered by the threat of AI disruption could cause another headache for software companies. Employees often receive shares as part of their compensation and managers may have to make up for the lost equity value by paying out more cash, Evans said. Any effort to buy AI startups to boost growth may add to the financial strain, he said. "We don't believe current prices reflect the terminal value uncertainty or the pressure on free cash flow," he said. A debate over the scale of the threat is raging on Wall Street. Strategists at JPMorgan Chase & Co said last week that software stocks could rebound following recent "extreme price action." They favor stocks like Microsoft and ServiceNow. There are areas of software Evans considers to be less vulnerable to disruption. In January, the fund manager increased holdings in infrastructure software firms that provide the foundation of systems which support consumer and enterprise applications. His investments in the sector include Cloudflare Inc. and Snowflake Inc. Recent results from infrastructure software companies Datadog Inc. and Fastly Inc. showed that demand for the plumbing for the internet is soaring. Datadog shares rose over 10% last week, while Fastly more than doubled. Evans also has a neutral view on cybersecurity software as he sees no immediate threat from AI. Still, less than 7% of his fund is invested in infrastructure software and cybersecurity stocks. Outside of those two sectors, Evans expects only a few companies will survive the painful shakeout ahead. He predicts that most will go the way of newspapers in the 2000s, when the print media was decimated by the internet. Investors should be "significantly underweight application software and they have to react quickly, because as the models get better, the disruption is accelerating," he said.

[3]

Salesforce and Friends Deserve This AI Squeeze

Product releases from Anthropic PBC last week triggered a nearly $1 trillion selloff of enterprise software stocks, extending a decline that's been on course for some time. Salesforce Inc., which sells customer relationship management software, and Workday Inc., which provides financial management software, are both down more than 40% over the past 12 months. On Wednesday, the market rout spread to wealth management firms and, it seemed, any company that appeared to be in the crosshairs of artificial intelligence. This sell-first, ask-questions-later moment is overdone. In the case of enterprise software makers, investors are missing a crucial technical distinction between vendors like Salesforce, and AI tools such as Anthropic's Claude Cowork that suddenly look like a threat. What AI can do increasingly well is the higher-level knowledge work that many software-as-a-service (SaaS) applications were built to facilitate. That part of the business of Salesforce and its peers is indeed under threat. But AI can't yet compete with their underlying, systems-of-record offerings, which process proprietary data like billing, compliance and audit trails for a corporate customer. "These are precisely our areas of strength," Madhav Thattai, an executive at Salesforce, tells me. He's right. Agents, the hot new AI tools that carry out tasks like booking an appointment instead of just answering questions, can't replicate thousands of bespoke business rules built up over years, areas where firms like Salesforce, SAP SE, Oracle Corp. and Epic Systems Corp., used by hospitals, are entrenched. Other SaaS executives have pushed back on the bears. SAP Chief Executive Officer Christian Klein argued on an earnings call in January that clever generative AI models couldn't work with the critical business data and workflows that are his company's bread and butter. As independent analyst and former venture capitalist Benedict Evans has noted, successful SaaS products are sparked by someone identifying a unique, organizational problem, mapping out a workflow and then coding it into software. That's how you get the complex, often niche workflows that become the plumbing infrastructure for banks, schools, retailers, hospitals and police departments. It's when SaaS firms also act as plumbers that things go downhill. The applications built on top of all that database infrastructure have long been terrible: clunky, unintuitive and overpriced, and sometimes insecure. To make matters worse, customers are often stuck using these systems because moving from one provider to another is a lengthy and expensive process. Sign up for the Bloomberg Opinion bundle Sign up for the Bloomberg Opinion bundle Sign up for the Bloomberg Opinion bundle Get Matt Levine's Money Stuff, John Authers' Points of Return and Jessica Karl's Opinion Today. Get Matt Levine's Money Stuff, John Authers' Points of Return and Jessica Karl's Opinion Today. Get Matt Levine's Money Stuff, John Authers' Points of Return and Jessica Karl's Opinion Today. Bloomberg may send me offers and promotions. Plus Signed UpPlus Sign UpPlus Sign Up By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service. "Software industry models in the U.S. are shaped around monopolization, offering low quality and bad security for high prices," writes Matt Stoller, director of research at the American Economic Liberties Project, a nonprofit that campaigns against monopolistic practices. Stoller, in his latest newsletter, describes a 2016 meeting with community bankers in which they derided their niche software vendors as "expensive" and "terrible." Swedish fintech company Klarna Group Plc stopped using software from Salesforce and Workday in 2024, replacing the incumbent vendors with tools from smaller SaaS companies with names like Deel and Neo4j, then using an AI coding tool called Cursor to build a more modern application layer on top. In other words, Salesforce customers like Klarna aren't just replacing their old SaaS software with AI tools. They're also using AI to build their own applications to better serve their needs, squeezing out the expensive interface layer while keeping the underlying data intact. The rather boring data management and compliance systems sold by big SaaS companies aren't what's under threat, but their apps are. And Salesforce sits right on the fault line of what's safe and what's vulnerable, being partly a system of record and partly a knowledge interface that AI tools are trumping. Last year Salesforce boldly tried to stave off the threat, becoming the first large tech company to sell AI agents with a program it called Agentforce. CEO Marc Benioff said the new platform was core to what Salesforce did, even suggesting the company could change its name to "Agentforce." But Agentforce's performance has been lackluster. Christine Marshall, a Bristol-based Salesforce trainer and one of the company's most recognized outside experts, wrote a surprisingly tepid review of the platform last year. After testing Agentforce on six common tasks, she found it only handled two of them well, and fumbled helping a user reset their password. Salesforce's Thattai wouldn't address the review when I asked him about it, saying that Agentforce behaved in a consistent and reliable way, even when paired with a large language model. Agentforce, ironically, uses AI models from OpenAI and Anthropic, the companies that now appear to be threatening its business. A market correction was needed for the inelegant applications that so many businesses are locked into. But SaaS companies have enjoyed high valuation multiples because they control both the infrastructure and interface. If technology from Anthropic and OpenAI can sit on top of those systems of record, they'll start to erode the pricing power of the SaaS companies that run them. That means that for enterprise software's bloated application layer, the age of easy margins may be over. More from Bloomberg Opinion: * Claude AI May Make Analyst Groupthink Even Worse: Parmy Olson * Who's On the Other Side of the Big AI Selloff?: Chris Hughes * Wall Street's Doom-Mongering on Software Is Bizarre: Dave Lee Want more Bloomberg Opinion? Terminal readers head to OPIN <GO> . Or subscribe to our daily newsletter .

[4]

Marc Andreessen made a dire software prediction 15 years ago. Now it's happening in a way nobody imagined | Fortune

On August 20, 2011, legendary venture capitalist Marc Andreessen published a blog post -- and an accompanying essay in The Wall Street Journal -- that would become the sacred texts of the Silicon Valley bull run. Titled "Why Software Is Eating The World," he argued that the global economy was undergoing a "dramatic and broad technological and economic shift" and that software companies were poised to take over large swathes of the industry. Fifteen years later, in February 2026, Andreessen's prophecy has been fulfilled in a manner that even the biggest bulls failed to predict. Software did indeed eat retail (Amazon), video (Netflix), music (Spotify), and telecommunications (Skype) just as Andreessen predicted, but the market got a $1 trillion shock in February because something was eating software itself. That something, of course, was artificial intelligence. Morgan Stanley's software analysts, led by Keith Weiss, offered a "gut check" this week in a major research note, arguing that "AI IS software" but also that software is growing so all-consuming that it is indeed starting to eat work itself. Andreessen's a16z has a core strategy of investing across enterprise software, including cloud, security and software-as-a-service (SaaS), but the $1 trillion-plus selloff dubbed the "SaaSpocalypse" cuts to the very heart of that model. Andreessen looks like he was more right than he knew about software eating the world. To understand the severity of the current shift, one must look back at the skepticism Andreessen was fighting in 2011. Following the trauma of the dot-com crash, he declared that the stock market "hated technology." While Apple was trading at a price-to-earnings ratio of just 15.2x amid immense profitability, investors constantly screamed "Bubble!" Andreessen claimed that companies like Amazon and Netflix were not merely speculative bets, but "real, high-growth, high-margin, highly defensible businesses" building a fully digitally wired global economy. He correctly identified that Borders was handing its keys to Amazon, that Netflix was eviscerating Blockbuster, and that "software is also eating much of the value chain of industries... in the physical world," such as automobiles and agriculture. For a decade and a half, he was right. The "creative destruction" he invoked -- citing economist Joseph Schumpeter -- decimated legacy incumbents and minted trillions in value for software insurgents. However, the AI revolution of 2022 onward and the SaaSpocalypse of 2026 suggest that the cycle of creative destruction has arrived at the doorstep of the software industry itself. Morgan Stanley's Weiss wrote of a "Trinity of Software Fears" currently driving down stock multiples by 33% that cut to a fundamental questioning of the software business model. While Andreessen saw software disrupting industries, Morgan Stanley sees AI disrupting labor itself. The analysts note that generative AI expands the capabilities of software to "contextually understand unstructured data," such as emails, PowerPoints, and verbal communications. This unstructured data represents over 80% of information in organizations today. Previously, software required a human operator to input and manipulate this data. Now, Wall Street fears that software can do it all by itself. "Generative AI represents a continuing expansion of what types of work and business processes software can now effectively automate," Weiss wrote, revisiting his team's initial estimate that enterprise software's total addressable market could grow by $400 billion by 2028. Three risks put that in question, principal among them that "as GenAI automates a broader swathe of work, the increasing productivity gains will result in a reduction in the number of employees necessary to execute those tasks." If software allows a company to cut its staff by half, it also cuts the number of software subscriptions it needs by half. After software ate the world, then, it appeared to start eating the revenue of its creators by eating the jobs of its users. Andreessen predicted in 2011 that "software programming tools... make it easy to launch new global software-powered start-ups," viewing this as a boon for entrepreneurs. Today, however, investors are beginning to view this democratized ease of creation as a threat to established software giants. One of the primary fears cited by Morgan Stanley is the rise of "do-it-yourself" (DIY) software. This is colloquially known as "vibe coding," where a user will ask the AI to code things in line with a certain vibe that they are going for. As AI code generation tools drastically lower the cost and skill required to write code, there is a growing fear that "companies will choose to develop more software themselves" rather than paying for expensive third-party vendors. Furthermore, there is the looming threat of "model providers" -- the creators of frontier AI models -- rendering traditional applications obsolete. The fear is that an AI agent could act as an "intelligent user interface," pulling together data and tools to automate workflows on the fly. In this scenario, the distinct "app" disappears, replaced by a single, omniscient model that serves as the operating system for the entire enterprise. Like other analysts (and several rattled SaaS executives), Morgan Stanley argued that the market's reaction is overblown, echoing Andreessen's 2011 sentiment that investors were ignoring "intrinsic value" right in front of them. The bank suggested that the "bear case arguments around GenAI appear to give too little credence to the ability of incumbent software vendors to participate in this innovation cycle." Andreessen once warned that "incumbent software companies like Oracle and Microsoft are increasingly threatened with irrelevance." In 2026, however, Morgan Stanley identified Microsoft, alongside Salesforce and ServiceNow, as the "Best Athletes" positioned to win. True, Salesforce is in "the eye of the storm" in terms of workflows expected to be disrupted by GenAI. But Weiss said that incumbents such as Salesforce are successfully pivoting to become "fast followers," integrating AI to solidify their moats rather than losing them. For example, Salesforce has seen its AI-related annual recurring revenue surge 114% year over year. Zooming out, Morgan Stanley said it sees a "path of innovation that actually looks relatively familiar": a combination of improving productivity, better use of tools to automate functions and software value "predicated on labor displacement." The difference now is the rapid pace of innovation compared to prior cycles and better tools on the market. It looking closely at Amazon Web Services and the shift in the early 2010s toward cloud computing. Even with the 33% pullback for software's equity value/sales multiple since October, the group is trading about 15% above the beginning of the cloud era. In a sequel of sorts to Andreessen's famous essay, his own firm has released new thought leadership (as it does quite regularly). Steven Sinofsky of a16z dismissed the idea of the "death of software" earlier this month, arguing that "AI changes what we build and who builds it, but not how much needs to be built. We need vastly more software, not less." He offered five predictions, including more software being made with new tools in a vastly more sophisticated way, but also an admission that "it is absolutely true that some companies will not make it," and endless invention and reinvention is the way of capitalism. A look back at the Fortune 500 archives show that is undoubtedly the case. In his 2011 essay, Andreessen concluded with optimism, calling the software revolution a "profoundly positive story for the American economy." He acknowledged challenges, specifically that "many workers in existing industries will be stranded on the wrong side of software-based disruption." That is where things may be scarily different this time. Even if software finds a way to recover its multiple and continue its upward trajectory, analysts are increasingly seeing a future of growing GDP and productivity without nearly as much human labor involved. Michael Pearce of Oxford Economics recently joined a group including Bank of America Research and Goldman Sachs warning that the U.S. economy is nearing a point where it won't need to keep creating new jobs to keep increasing output. Google DeepMind's Nobel-winning co-founder, Demis Hassabis, recently told Fortune Editor-in-Chief Alyson Shontell that he was excited about the world of "radical abundance," even a "renaissance" ahead, but there will be a 10- to 15-year shakeout until we get there. That could come as the economy figures out what to do with all the labor that software has eaten.

[5]

Wall Street Analysts Tom Lee and Dan Ives Disagree on Software "Armageddon": One Says "Buy" While the Other Says "Layoffs Are Coming." Who Is Right?

The software sector is in turmoil. Is the worst to come, or is this a generational buying opportunity? It has been a difficult start to 2026 for the software industry. New artificial intelligence (AI) product releases from the likes of Anthropic have investors questioning whether AI agents will replace or merely buy fewer software licenses. What's interesting is that two of the most bullish technology analysts on Wall Street, Tom Lee and Dan Ives, appear to have opposite takes on the sell-off: one thinks the software disruption is real, and the other calls the software meltdown a "golden buying opportunity." So who is right? Disruption, or "DeepSeek" moment? Some investors may recall that one year ago, the entire AI complex sold off when Chinese AI lab DeepSeek released an extremely efficient large language model (LLM) that cost a fraction of what other models cost to train. However, that panic-sell turned out to be a golden buying opportunity. Thanks to "Jevon's Paradox," the idea that use of something increases as it gets cheaper, AI investment has only accelerated from that point. Could the same thing happen here with software? While the S&P 500 is about flat for the year, the largest software exchange-traded fund, the iShares Expanded Tech-Software Sector ETF (IGV +1.54%), is down a nauseating 21.7%. The sudden and widespread sell-off seems to have come on the back of releases of increasingly proficient artificial intelligence applications, with the worry accelerating into February with the release of Anthropic's Opus 4.6 model and related applications Claude Code and Claude Cowork. One prominent feature of Opus 4.6 is that it enables agent "swarms" for Cowork. Or, instead of one agent doing many different things one after the other, 4.6 enables agent "teams" that can divide up work to do them simultaneously on a computer. This is just one of many rapid improvements Anthropic and other models have made over the past few months, and it's causing a lot of consternation in traditional enterprise software stocks. After all, if AI agents are now able to write software and perform all of these functions that humans recently performed with software as their primary tool, does the importance and value of the underlying software go down? Tech bulls divided What's interesting is that this AI wave is so rapid, and the software stocks have declined so much, that even the more bullish tech analysts on Wall Street are divided. Fundstrat's Tom Lee recently said in an interview that "it's not lost on the Fed that AI is wreaking havoc across software now, and that means that job losses are soon to follow." Of note, Lee has been one of the more bullish analysts on Wall Street, especially when it comes to tech. On the other hand, Wedbush sell-side analyst Dan Ives chimed in differently, saying, "In our opinion, in my career, going back to the late Nineties, it is the most head scratching sell-off relative to what I believe is going to be the opposite as it plays out that I've ever seen." Ives believes that AI use cases will explode so much that overall usage of critical software will increase by leaps and bounds, making up for any pricing pressure. These two perspectives might not be 180 degrees from each other, and differences may lie in the details. What executives are saying For the record, many tech executives say today's fears are overblown; however, many tech CEOs also have an incentive to say that. Nvidia (NVDA +2.89%) CEO Jensen Huang recently said that AI will probably use software tools rather than inventing entirely new ones. And that, of course, is likely to be the case. Why build a wholly new tool when AIs can merely use what already exists? But mere usage isn't the full story when it comes to these stocks. There is also an argument that since AI agents will be using tools in this scenario, software companies won't be able to sell as many licenses, or "seats," to large corporations. But countering that notion, in a recent CNBC interview, ServiceNow (NOW +1.80%) CEO Bill McDermott said that if that scenario happens, ServiceNow has a hybrid pricing structure that can operate either on a seat-based or usage-based model, and it's up to customers to choose. Meanwhile, software companies appear to be falling over themselves to partner with and integrate with LLMs to deliver tangible outcomes. ServiceNow and Figma (FIG +5.28%) both recently announced partnerships with Anthropic, while Salesforce (CRM +1.80%), another software giant caught up in the downdraft, inked a deep partnership with OpenAI in October of last year. But if these software companies integrate LLMs for a large part of their future value, do the LLMs get a bigger piece of the pie? Can software companies charge what they've been charging if a lot of the value comes from a third-party LLM? How does this shake out? While some software companies may come out the other side of this OK, investors should prepare for a period of disruption and uncertainty. It also doesn't help that software stocks have generally traded at higher valuations than most other stocks over the past decade or so coming into this moment, given their "asset-light" business models and strong growth prospects. One possible bulwark is that legacy enterprise software providers such as Salesforce and ServiceNow have a wealth of data from large enterprises in their systems dating back years or even decades. If a newcomer developed its own AI-generated software with similar capabilities, would it be able to persuade a large enterprise to rip out all its data and migrate it to a new, unproven upstart? Or would the incumbency and trust of the older platform win out? As it stands, I'd bet that the incumbents figure out a way to survive. But the certainty on this assumption is low. If a newcomer comes along with similar capability at one-tenth or even one-twentieth the price or less because building software is so much easier, would that be enough to persuade enterprises to switch? At the very least, could customers demand lower prices? However, would usage increase so much that overall dollars would grow even if the price per token or price per instance came down? These answers won't be answered for a while. As such, I'd expect the valuations of major software companies that aren't building their own LLMs to remain at lower valuations than their recent history. And while this sell-off could make for a great long-term buying opportunity, I don't think a rerating higher is going to happen anytime soon.

[6]

Market Outlook: AI divides software stocks into winners and losers

Software stocks are under pressure after weak guidance from Palo Alto Networks added to concerns that artificial intelligence could disrupt traditional software models. Investors are reassessing which companies will benefit from rising AI adoption and which may face structural pressure. BNN Bloomberg spoke with Matthew Tuttle, CEO and chief investment officer at Tuttle Capital Management, who said cybersecurity and data infrastructure firms are positioned to benefit from AI growth, while workflow-based and outsourcing companies face displacement risk. Read the full transcript below: ANDREW: Shares in Palo Alto Networks came under pressure today, with its third-quarter forecast missing expectations. And, of course, the software sector in general has been hammered amid fears that artificial intelligence will radically change the business of software and services. Let's get more from Matthew Tuttle, CEO and chief investment officer at Tuttle Capital Management. Matthew, thanks very much for joining us. Maybe we could put up a five-year chart for Palo Alto. At one stage, I think investors thought, well, they're the industry leader in cybersecurity, the need is only growing -- how could you go wrong? MATTHEW: Yeah, and we're big believers in cybersecurity. We like CrowdStrike a lot better than we like Palo Alto. So we run one of our ETFs -- MEMY is our 20 top thematic ideas -- and CrowdStrike is one of those names. You know, all of cyber has kind of gotten thrown out with the bathwater in the software selloff. But we really see cybersecurity as an area that's going to get increased demand from AI. And certainly, you're going to need it if quantum fulfills those promises. So we would definitely be buying CrowdStrike. ANDREW: Sorry -- Palo Alto and CrowdStrike? MATTHEW: Well, CrowdStrike is our favourite. Oh yeah, I do like the cybersecurity area. So Palo Alto, certainly, I wouldn't mind buying on weakness, but CrowdStrike is our favourite in this area. ANDREW: It, too, is down. Why is that? Why have investors gone cooler on these cybersecurity giants? MATTHEW: Yeah, and it's really what's happening across software. So last year was the AI rising tide that lifted all boats in technology. Then all of those names got extended. Now, all of a sudden, people are realizing there are companies that are probably going to get helped by AI, but then there are companies that are going to get crushed. And the initial reaction was sell everything in software. So that's why cybersecurity -- Palo Alto, CrowdStrike -- all of those names sold off. We think this is an opportunity. We'd be buying some of those names, but then some we would definitely be avoiding. ANDREW: Let's get into those. DocuSign -- you're not keen on that one. It was a darling during the pandemic. MATTHEW: DocuSign is a lifesaver for me today, but it's one of those stocks that I think, once agentic AI fully comes online, it's going to be very easy for them to integrate what DocuSign brings to the table into that workflow. So that would be a name that I would not want to own here. ANDREW: Right. So you basically feel it can be automated by AI? MATTHEW: Yeah. I mean, there are some companies that have sold off because of the AI fear that I think is warranted. DocuSign is definitely one of them. ANDREW: What about monday.com, MNDY on Nasdaq? Again, you're not too keen on that one. MATTHEW: No. Anything that's got some sort of workflow app to it that agentic AI could fairly easily incorporate -- we would be avoiding those names. We do think those are names that are likely to get hurt as AI and agentic AI come more on board. So we would be avoiding those as well. ANDREW: And then finally, EPAM -- a stock I'm not familiar with. The symbol is EPAM. Can you remind us what they do and why you're less keen on this one as well? MATTHEW: Yeah. So anything IT services outsourcing, that's something I definitely would avoid. So that includes EPAM. I see that every day -- we do have an outsourced IT provider for our company. I'm increasingly using AI more and more for basically doing our IT work, and I can foresee -- and hopefully they're not listening -- a time where we replace them with AI. So anything outsourced, anything IT outsourcing, I think AI and agentic AI can take that over. ANDREW: Talk to us about Snowflake, SNOW. You feel that they're less vulnerable. Why is that? MATTHEW: I feel that they're less vulnerable. So we kind of spread this out -- what are the tollbooth companies, the companies that live somewhere along the chain of agentic AI, where you know how things are going to happen? Snowflake -- it's not a company that we own personally in client portfolios or in our ETFs. But I certainly would not be averse to buying the dip here. We think they are one of the AI tollbooth companies. ANDREW: What about the giants such as Microsoft? I don't know if that's a stock you cover. MATTHEW: Oh yeah. One of our ETFs is MAGO -- it's the Mag Seven. I think if you look at all of the themes, and we teach people this in thematic investing, one or more of those companies are the obvious winners in a lot of this. Microsoft is a behemoth. Anytime you can get Microsoft on a dip, I would be buying Microsoft. ANDREW: Right. The stock's down a lot this year. Would you be putting new money into it, then? MATTHEW: I would be putting new money into Microsoft. And really, whenever people tell you the Mag Seven is dead and it's going to be the other 493 companies in the S&P, that's when I want to buy the Mag Seven. ANDREW: Maximum pessimism. Thank you very much, Matthew. I really appreciate it. MATTHEW: Thank you. ANDREW: Matthew Tuttle, CEO and chief investment officer at Tuttle Capital Management. ---

[7]

Top-performing fund warns software firms face 'existential threat...

A top-performing asset manager is warning that few software firms will survive the rapid growth of artificial intelligence - which could potentially automate most of their services. Nick Evans, a Polar Capital fund manager, saw his $12 billion global technology fund beat 99% of peers over a one-year period and 97% over five years by selling off software stocks ahead of the crowd, according to a Bloomberg report. "We think application software faces an existential threat from AI," Evans told Bloomberg. Software stocks have been slammed over fears that AI, particularly tools like Anthropic's Claude Cowork, will automate application software - which helps users complete tasks like writing documents, creating spreadsheets and managing payrolls. An exchange-traded fund tracking the US software sector is down more than 22% so far this year. Industry leaders like Salesforce and ServiceNow are down 25% and 27%, respectively. Evans said Polar Capital has sold virtually all of its holdings in software firms like SAP SE, ServiceNow, Adobe and HubSpot - telling Bloomberg that the fund "won't go back to these companies." Investors should be "significantly underweight application software and they have to react quickly, because as the models get better, the disruption is accelerating," Evans said. The market rout could also hurt software firms in the long run, since many employees receive shares as part of their compensation - and managers could be forced to make up for the equity losses by shelling out more cash, according to Evans. "We don't believe current prices reflect the terminal value uncertainty or the pressure on free cash flow," he told Bloomberg. Software companies are facing heated competition not just from AI giants, but from their own clients, who are rushing to develop in-house AI tools to cut down on costs. Evans told Bloomberg he expects only a few companies to survive a painful reckoning ahead - comparing it to the internet's blowout impact on print media in the 2000s. Some companies - like SAP, a German firm that makes complex software packages - will be more resilient during this market shift, Evans said. But AI tools are "getting dramatically more powerful," so it's unclear how even the most specialized software firms will fare in the long term, he added. The outperforming hedge fund is bullish on chipmakers, with semiconductor firms making up seven of its top 10 positions as of the end of January. Its top holding is Jensen Huang's Nvidia - which accounts for nearly 10% of the total portfolio. The fund is also optimistic on firms that make networking gears and fiber optics, and those that provide energy infrastructure critical for power-hungry data centers. Evans also increased holdings in infrastructure software firms like Cloudflare and Snowflake in January, and said he has a neutral view on cybersecurity software, which doesn't appear to face any immediate risks from the growth of AI. Wall Street is still debating the future of the software sector in the face of artificial intelligence. JPMorgan Chase strategists took a more optimistic view last week, writing that software stocks like Microsoft and ServiceNow could rebound following recent "extreme price action."

[8]

The 'Software Winter' | Investing.com UK

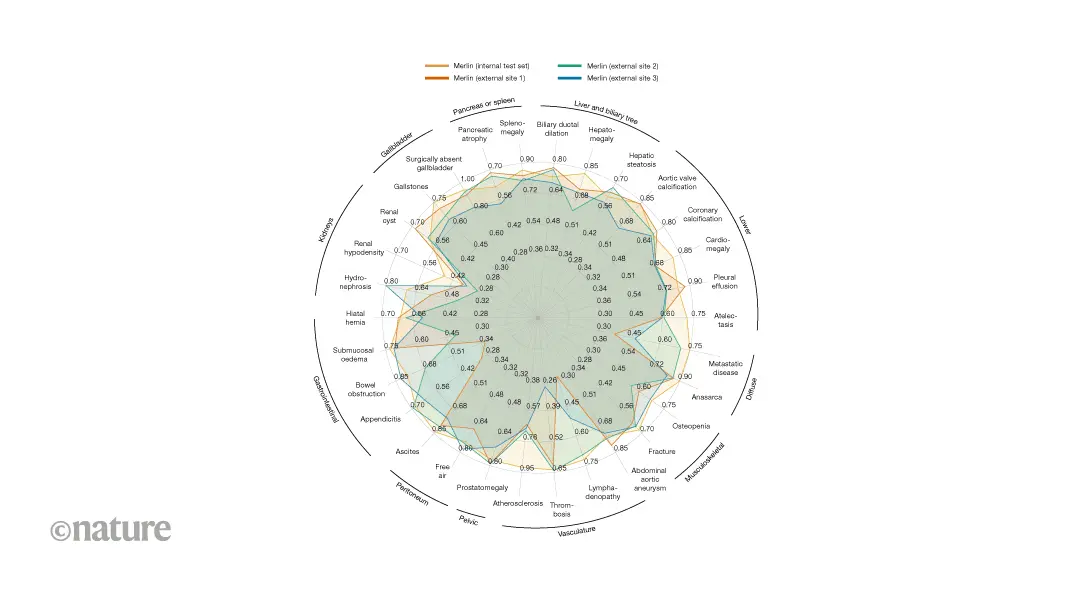

The iShares Expanded Tech-Software ETF (NYSE:IGV), treated as the benchmark for the sector, has slid almost 30% from its September peak, a sharp reversal for what was considered one of the market's safest growth franchises. Every technological cycle produces its moment of doubt. For software, that moment may be now. After years of uninterrupted dominance, the software sector has entered a period of sharp repricing and rising uncertainty. Artificial intelligence is becoming embedded directly into the workflows that run day-to-day operations. As this integration deepens, it changes how work is executed and how software earns its value. Markets are beginning to adjust. Artificial intelligence has moved from experimentation to full deployment in a short period of time. The change goes beyond adding smarter features to existing software. Entire tasks that once required teams of employees are being automated and executed at speed. Spending patterns highlight the acceleration. The "Magnificent 7" hyperscalers are projected to invest $650-700 billion in 2026, a 60% rise from 2025, led by Amazon's (NASDAQ:AMZN) $200 billion budget. Capex-to-sales ratios have expanded from around 10% to above 25%. About three-quarters of that investment is directed toward chips, data centres, networking, and power. Adoption data confirms the shift. According to Ramp, AI penetration among US businesses jumped from 5% in 2023 to 44.5% by July 2025. Early adopters report measurable productivity gains and cost efficiencies. Slower players face rising competitive pressure. Across business functions, McKinsey estimates that more than 88% of companies use AI in at least one area. In Audit and Accounting, traditional ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) systems such as SAP (NYSE:SAP), Oracle Financials, and Sage rely on rule-based processes, but AI platforms like MindBridge and BlackLine now use machine learning to detect anomalies and fraud in real time, reducing manual audit work. In Sales and CRM, Salesforce (NYSE:CRM), Microsoft Dynamics, and HubSpot focus on pipeline tracking, but AI tools such as Salesforce Einstein GPT, Microsoft Copilot for Sales, Gong, and Clari enhance performance by analysing calls, predicting deal outcomes, and automating recommendations. In IT Service Management, ticket-based platforms like ServiceNow (NYSE:NOW) and BMC face competition from AI agents such as Moveworks and Aisera that autonomously resolve requests. All of this inevitably brings the future of traditional software companies into focus. AI is no longer confined to refining existing products; it is beginning to reshape the very business functions those products were designed to support, shifting from structured workflow management toward autonomous, data-driven decision-making and execution. Irrespective of how fully that shift is reflected in valuations, the perception alone has introduced a layer of market uncertainty. The sector's first major drawdown began around mid-2021 as generative AI technologies such as ChatGPT entered the mainstream. By mid-2025, sustained underperformance pointed to something more structural, as investors reassessed the durability of traditional software models considering AI's expanding capabilities. Frontier developments have reinforced that reassessment. DeepSeek shipped a $6 million AI model, signalling that advanced capability no longer requires hyperscale capital. Anthropic launched Cowork, deploying AI agents capable of autonomously handling legal review, sales operations, and compliance. Tools such as Cursor and GitHub Copilot now generate production-ready code, illustrating that AI systems can increasingly build software for AI. Market reactions were swift. Following Claude's Cowork launch, Nifty IT declined 6%, Infosys ADRs fell 8.4%, Cognizant dropped roughly 10%. The iShares Expanded Tech-Software ETF (IGV) is down 30% from its September high. Source: Factset The market is currently treating software as a single asset category; it is not. Beneath the surface sit two structurally different businesses valued as one: software applications, which are software humans click on, and infrastructure software, which is software other programs call. Artificial intelligence is compressing the economics of the first but structurally reinforcing the second. Software applications encompass the tools humans interact with throughout the day: visual dashboards, customer relationship management systems, project management platforms, coding environments, legal workflow tools, and productivity suites. Think of platforms like Salesforce, HubSpot, ServiceNow, or Monday.Com (NASDAQ:MNDY). It is a segment expected to generate around $820-850 billion in revenue by 2026 and grow by 11-13% annually, with a 9.5% CAGR projected through 2029. They are typically monetised on seat-based SaaS models in which revenue scales directly with headcount. For more than a decade, the formula was powerful and predictable. Enterprise hiring drove licence expansion, which in turn drove recurring revenue growth. That connection weakens when AI performs the underlying task. If an AI agent completes the work of an analyst, developer, or support associate, the enterprise does not simply reduce labour costs, it also eliminates the associated software seat. Seat-based SaaS compresses as headcount compresses. Technology layoffs reached approximately 151,000 in 2024, according to Times Now News (2024), with estimates suggesting the figure may approach 120,000 in 2025. Workday (NASDAQ:WDAY) has noted customers committing to structurally lower headcount assumptions at renewal, with that discipline expected to persist into 2026. Growth that accelerated sharply after the pandemic has normalised into the mid-teens and is moderating further. The deeper pressure is substitution rather than augmentation. Copilots enhance user productivity within existing applications, and agentic systems execute multi-step workflows autonomously. Anthropic's Claude Cowork is designed to complete processes end to end rather than assist incrementally. When a single agent can replicate the output of several junior employees, enterprises require fewer staff and fewer licences. The traditional seat-based moat begins to erode. Gartner forecasts that by the end of 2026, 40% of enterprise applications will transition toward outcome-based agentic pricing rather than per-user logins. Infrastructure software operates on a fundamentally different economic model. It consists of APIs, databases, event-streaming systems, observability platforms, authentication layers, and cloud infrastructure. It is not interacted with by end users; instead, other software integrates with it directly. Companies like MongoDB (NASDAQ:MDB), Snowflake (NYSE:SNOW), Datadog (NASDAQ:DDOG), Cloudflare (NYSE:NET), and Twilio (NYSE:TWLO) exemplify this group. Unlike human-facing tools, these companies monetise usage rather than headcount. They charge per workload, per compute, or per data consumed, making their revenue more usage-sensitive and less tied to the number of human users. A human performing a task may generate a limited number of API calls per hour. An AI agent performing the same task can generate hundreds per minute, continuously querying databases, logging activity, authenticating requests, and triggering downstream services. Infrastructure providers do not distinguish between human and machine traffic. They charge on consumption. As AI workloads scale, infrastructure usage scales with them. According to Forrester estimates, the infrastructure software segment, covering cybersecurity, data management, network monitoring, and operating systems, is expected to reach $580-610 billion by 2026, growing at a healthy ~13.3% CAGR between 2027 and 2029, outpacing traditional application software growth. Recent months have brought a significant correction across US software equities, erasing approximately $300 billion in market value. The decline appears less about short-term earnings pressure and more about a structural reassessment of traditional SaaS economics amid accelerating AI adoption. For much of the past decade, SaaS growth relied on a simple formula: enterprise hiring drove new software seats, seat expansion fuelled recurring revenue, and high retention supported premium valuation multiples, which peaked above 20x EV/Sales in 2020-2021. That clear link between headcount, revenue, and valuation is now under pressure. What concerns investors is not simply AI's growing presence in enterprise software, but its economic implications. As systems increasingly draft code, review contracts, reconcile financial data, and update CRM records with minimal oversight, output begins to decouple from headcount. For years, SaaS growth scaled predictably with employment expansion. That linkage is becoming less reliable. If fewer users are required to generate the same or greater productivity, per-seat pricing loses some of its structural advantage. A central driver of the recent software correction is the shifting composition of technology spending. As companies prioritise AI capabilities, budgets are migrating toward infrastructure and model development, narrowing the space for traditional SaaS subscriptions. Investment is flowing instead to the underlying architecture that supports AI, namely data storage, scalable compute, monitoring, and automation. The extraordinary rally of 2020-2023 had pushed software valuations to unsustainable levels. Many SaaS firms traded at lofty multiples assuming continued hypergrowth and low interest rates. As inflation drove bond yields higher, the present value of future cash flows fell, prompting investors to reassess what they were willing to pay for growth. By early 2026, the average SaaS EV/Sales multiple was approximately 3.3x, far below the 2020 peak above 20x and near a five-year low. This suggests market pessimism may have exceeded what fundamentals justify. Core business metrics -- recurring revenue, high retention and strong margins -- remain solid across leading companies. Artificial intelligence is not ending the software industry. It is forcing it to evolve, testing its durability and reshaping how value is created across the technology stack. For more than a decade, application software thrived on a predictable equation: seat expansion drove recurring revenue, which justified premium valuations. As AI moves from augmenting work to executing it, that linkage is being reconsidered. Infrastructure platforms stand to benefit as AI workloads scale, while models tied closely to headcount face structural pressure. The deeper disruption lies elsewhere. The services economy built on labour arbitrage and the billing of human hours layered on top of software is far more exposed. Software remains viable; labour arbitrage may not.

[9]

Software Apocalypse: It's the model not the sector.

Anthropic's release of Claude Cowork industry plug-ins on January 30 sent a message that Wall Street heard loud and clear: frontier AI labs are no longer sticking to building tools for developers. They are expanding to build the replacement for enterprise software itself. Within 48 hours, Thomson Reuters fell 16%, RELX dropped 14%, Wolters Kluwer lost 13%, and Monday.com was down over 20%. Jefferies trader Jeff Favuzza called it a "SaaSpocalypse." However, the market probably overreacted and threw the baby out with the bathwater by hitting sell on every software stock. For the past week, we have been looking at every corner of the market to properly measure who will suffer the most and the least from this SaaSpocalypse. We found that there are three types of SaaS that will each have a different fate, and decided to build a quadrant to reflect this reality. Feel free to play around with this chart via this link. To really understand who the winners and losers of this new evolution of SaaS companies will be, we will first have to look how each of them make money as it is the best litmus test to judge a company's health. These are companies whose core asset is proprietary, curated data that cannot be reproduced by scraping the internet or training a model on publicly available sources. Think of Thomson Reuters' Westlaw (that has decades of attorney-curated case law), Intuit's TurboTax (100 million Americans' tax returns and financial records), Experian's credit bureau (data on 1.4 billion people and 200 million businesses), or Wolters Kluwer's UpToDate (clinical decision data used by 3 million clinicians globally). Their business model is licensing access to irreplaceable datasets. In an AI world, their data becomes more valuable, not less, because AI models need high-quality, domain-specific data to produce trustworthy outputs in fields where getting it wrong has legal, medical, or financial consequences. As investor Elad Gil put it in a recent McKinsey interview: "Data as some useful input to do something better for your business is incredibly valuable. Data as a core differentiator of your business is rarer. And data as a primary competitive advantage applies to a very, very small number of companies." These are the companies most people think of when they hear "SaaS": per-seat subscription tools that automate business processes for human users. Salesforce for sales teams. Workday for HR departments. Monday.com for project managers. Adobe for designers. ServiceNow for IT workflows. All software company CEOs are now scrambling to acquire AI companies, therefore calling Thoma Bravo, a Private Equity specialist in acquiring distressed tech startups among others. Their revenue is a direct function of how many humans sit in front of screens clicking buttons. The business model is essentially a gym membership for the office: you pay per person, per month. Just like gyms, SaaS companies make money only when you're not really using the service. The problem is obvious. When one employee with an AI agent does the work of five, you do not need five licences anymore. You need one. And the gym's revenue just dropped 80%, not because the equipment got worse, but because the customers disappeared. Databricks CEO Ali Ghodsi made a sharper observation recently: AI is not killing SaaS by replacing enterprise systems. It is killing them by making their interfaces irrelevant. For decades, the moat these companies relied on was UI complexity: millions of people trained on Salesforce, SAP, or internal dashboards. When workers can instead ask questions and take actions through natural language, that moat evaporates. Software becomes plumbing, not destination. These are companies building the connective tissue between raw AI models and enterprise operations: the "operating system" layer that neither the AI labs nor the workflow tools own. Palantir is the purest expression of this "platform". Snowflake and Databricks occupy adjacent territory on the data infrastructure side. ServiceNow is attempting to pivot here from its workflow origins. Their business model is fundamentally different from per-seat SaaS. They charge for outcomes, data throughput, or platform access rather than counting human users. As Goldman Sachs CIO Marco Argenti described in his 2026 AI outlook: companies will shift from deploying human-centric staff to deploying human-orchestrated fleets of specialised multi-agent teams. These hybrid teams of humans and machines will charge clients by tokens consumed (the units of data used by AI models), not seats occupied. This is the "agent-as-a-service" economy. Palantir's Ontology platform is the clearest example of what this looks like in practice. It functions as a digital twin of an entire organisation: not just tables and databases, but real-world objects (employees, aircraft, purchase orders, threat actors) with their relationships, properties, and business logic mapped as a living model. AI agents operate on Ontology with full enterprise context. The platform is model-agnostic (it works with GPT-4, Claude, Gemini, Llama, or any custom model), meaning better and cheaper AI models make the platform more powerful without threatening its position. The selloff unfolded in three discrete shocks over ten days. Anthropic released eleven industry-specific plug-ins for its Claude Cowork autonomous agent, spanning across legal, finance, sales, marketing, customer support, data analysis, and enterprise search, each capable of automating end-to-end professional workflows. The blog post didn't mash words: "Tell Claude how you like work done, which tools and data to pull from, and how to handle critical workflows." Wall Street heard it as a direct assault on every per-seat SaaS vendor in existence and hit sell on every SaaS stock they could find. As a consequence, Thomson Reuters cratered 16% in 48 hours. RELX dropped 14%. Wolters Kluwer fell 13%. LegalZoom lost 20%. Some had it coming, others not. Goldman Sachs' basket of US software stocks sank 6% in a single session, its worst day since the April tariff shock. Total single-day US software losses hit $300B. The IGV iShares tech-software ETF hit its most oversold level relative to the S&P 500 in its 25-year history. Jefferies called it the largest relative oversold reading they had ever recorded. Anthropic released Claude Opus 4.6 (1-million-token context, "agent teams" coordinating multiple AI workers in parallel, native Excel and PowerPoint integration, outperforming GPT-5.2 by roughly 144 Elo points). The same day, OpenAI launched Frontier, an end-to-end enterprise platform for building and deploying AI agents across business systems, with early customers including Uber, State Farm, Intuit, and Oracle. Two frontier AI labs, on the same day, both saying: we are coming for your enterprise software contracts. By February 6, the S&P 500 Software & Services Index sat more than 20% below its October 2025 peak. Total market cap destroyed: more than $1 trillion since January 28. The AI labs are raising and spending at a pace that dwarfs anything the software industry has ever seen. Consensus capital expenditure estimates for the four largest hyperscalers (Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft) in 2026 now exceeds $600B, revised upward repeatedly since October 2024. Anthropic's revenue trajectory highlights the demand for these services. From $1B annualised revenue at the start of 2025 to $9B by year-end (9x in twelve months), the company is now targeting $18B for 2026 and closing a $20B+ funding round at a $350B valuation. Claude Code alone hit $1B in ARR within six months of launch, described as the "fastest-growing product of all time." As a comparison, Salesforce took 17 years to reach $18B in revenue. Anthropic is on track to do it in two. The initial selloff targeted the obvious victims: horizontal SaaS companies with per-seat pricing models. But the fear is spreading to corners of the software market that most investors assumed were protected. Dassault Systemes, the French industrial software giant, crashed 22% on Wednesday, 11 Feb: its largest single-day decline on record, wiping out roughly €6B ($7.1B) in market value. Dassault creates "virtual twins" of complex machines using simulation software. Its full-year 2025 revenue was flat at €6.24B, and 2026 guidance of 3-5% growth badly missed analyst expectations of 5.9%. Software revenue dropped 5% in Q4. Licence sales fell 7%. What scared the investors was not only the weak growth. It was the AI narrative behind them. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang recently described Dassault as being at the "epicentre of the next frontier of artificial intelligence." But that frontier, "world models" (AI systems that simulate and navigate the physical world), is exactly what threatens to commoditise Dassault's industrial digital twin offering. Former Meta Chief AI Scientist Yann Le Cun has started fundraising for his stealth startup called AMI Labs, focussed on building these very 'world models' that could endanger Dassault Systèmes' business. Additionally, Nvidia's own Omniverse platform, combined with open-source physics simulation models, could replicate much of what Dassault's 3DEXPERIENCE platform does, at a fraction of the cost. Dassault Systèmes' P/E has compressed from 35x to 20x. The lesson here is: the cheapest models will eat the low hanging fruit first. The tech-savvy firms, the cost-cutters, the SMBs and nimble startups that are already comfortable with AI tools will adapt to this new reality the quickest. They will cancel their Monday.com subscriptions, build internal tools with Claude Code, and replace junior staff with AI agents. This cohort of companies is already moving: SaaStr reports it runs an eight-figure business with single-digit headcount and 20+ AI agents, down from 20+ full time employees. This is a deadly blow to "workflow providers" as they get cannibalised by internal tools and orchestration agents. The carnage is concentrated but not contained. Declines from 52-week highs as of early February: For years, giants such as HubSpot and Atlassian flourished by taxing human productivity through a monthly fee for every 'seat' a company filled. However, as AI moved from simple assistance to autonomous agency, the market realised what was going on: the workforce of the future would be digital rather than human-only. Investors panicked as they realised that an AI agent does not need a Figma login or a Workday account to function. The resulting crash in these stocks represented the death of the 'per-seat' economy, as capital rotated aggressively from the tools that humans use to the intelligence that replaced them. Every single name here is in negative territory on a one-year basis except MongoDB (+25%) (who profits massively from the agentic deployment in enterprises, and Zoom (+11%) (who investors are using as a proxy for Anthropic exposure via Zoom's participation in its Series C round). SaaS companies like Adobe, Salesforce, Workday, and ServiceNow were treated as "growth" stocks throughout the pandemic era. COVID forced digitalisation compressed a decade of enterprise software adoption into 18 months. Suddenly every company needed cloud-based collaboration, CRM, HR, and creative tools. SaaS stocks re-rated to 30-50x forward earnings on the assumption that this growth trajectory was permanent. But this dream scenario didn't last long, as growth slowed, but the valuations remained sky high. It was propped up by two temporary tailwinds: a low interest rate environment that made future cash flows worth more, and the first leg of the AI era (2023-2025) where large language models were new and promised increased efficiency for employees and existing workflows. The narrative was: "AI makes your Salesforce reps more productive, so you buy more seats, not fewer." That was the narrative that led to the SaaSpocalypse on Jan 30th. The enterprise AI use cases demonstrated by Claude Cowork and OpenAI Frontier go far beyond what anyone imagined during the ChatGPT honeymoon phase. When execs realised that these are not productivity boosters only for human workers but instead were autonomous agents that replaced the human workers entirely, their whole worldview changed almost overnight. They learned to make the distinction between an existential threat disguised as a temporary tailwind. Better late than never? Companies that were trading at 30-50x forward earnings on the promise of everlasting 20%+ revenue growth are now trading at 12-20x as the market asks the question on whether their competitive advantage is really as deep as they previously thought. To add fuel to the fire, the codebases at these companies took decades to build at a cost of billions of dollars. That accumulated software was capitalised as intangible assets on SaaS balance sheets, representing a good chunk of their enterprise value. But with Claude Code or Cursor, what took senior engineers months can now be done in 48 hours, and junior engineers usually turn up to product meetings with the product entirely built using Claude Code in a matter of hours. The technical moat these SaaS players had is vanishing, making SaaS a distribution layer instead of their previous product excellence that drove the sky high valuations. There are some concerns about AI that keep the SaaS companies from losing everything overnight. Firstly, AI is massively loss making, as OpenAI ended 2025 with $20B+ in Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) but faces projected 2026 losses of roughly $14B and cumulative losses through 2029 are estimated at $115B. Profitability is not expected until 2030. Anthropic targets breakeven by 2028. The cost of training frontier models continues to rise even as the cost of per unit inference continues to fall. We spoke about this shift to inference in a previous essay. This gives much-needed time to the "data owner" SaaS companies to play catch-up and monetise their positions (like the Intuit-OpenAI deal). Secondly, AI is largely unregulated. There are no seat minimums, no licensing requirements, no professional standards for deploying an AI agent that handles customer support or writes legal briefs. The barriers to adoption are essentially zero for any company willing to experiment, which accelerates the cannibalisation of SaaS seats. While the lack of regulation here will accelerate the "workflow substitution", it won't be able to touch the US Food & Drug Authority-validated systems, the credit bureau infrastructure or the lethal side of military use. Finally, and most importantly, AI does not have a settled business model of its own. Despite the size of these frontier labs, they are still in a "startup" phase without a fixed business model, without a fixed customer base, and with skyrocketing costs. To address that, AI labs are trying to be infrastructure providers (like Cisco during the dotcom boom), platform companies (like Palantir), and application vendors (like the best-in-class SaaS companies) all at the same time. They are competing with their own customers (building CRM-like features while selling API access to companies that build CRMs). This instability creates opportunities for incumbents on the "data owner" & "platform" side that adapt quickly, but it also means the disruption is chaotic and unpredictable. What we believe will happen over the next 2-3 years is the very painful transition away from the per-seat business model that SaaS vendors have cherished for the past two decades. Per-seat pricing in today's environment is becoming extortionate. When one AI-augmented employee does the work of five, charging $150 per seat per month for each of those five seats is a tax on inefficiency that CFOs will not tolerate. SaaStr's analysis shows that at Salesforce, price increases account for roughly 72% of forward growth (6.3 percentage points of price hikes against 8.7% total ARR growth). Interestingly, Salesforce is trying to turn "AI that works" into a business model shift: moving beyond charging only for human seats, it is pricing agentic output as usage by taking Agentforce from a simple $2 per conversation to Flex Credits priced per agent action (20 credits per action, positioned as $0.10 per action). The clever part is the bridge between old and new spend, because the Flex Agreement lets customers convert user licences into Flex Credits and back again, so budget can flow from human licences to digital labour as workflows automate. We are still very early to what the next pricing models look like, as Salesforce is just one example. Here are some hypotheses on where the next business model for software companies could look like in the age of agents: You pay for the result, not the process. Think of it as similar to the success fee model in M&A advisory or executive search: the software vendor earns a percentage of the value created, not a monthly retainer regardless of output. This is high-margin but hard to standardise. You pay for tokens consumed (millions of tokens of AI processing) or "units of cognition," as Elad Gil described to McKinsey: "Instead of buying customer success seats, you're buying customer support queries that are answered." Salesforce's Flex Credits and similar models are early versions of this. Companies like Palantir negotiate custom contracts based on the specific enterprise use case, data volumes, and operational requirements. They get this information through their "Forward Deployed Engineers" who are technical consultants who spend weeks in the prospective enterprises, making an extremely detailed graph of how the company works and deciphers their operational pain points. Anthropic has started trialling this business model where they have their FDEs deployed at Goldman Sachs for 6 months, to co-develop specific tools that their organisation will require. This is the highest-value approach but requires deep integration and long sales cycles. Palantir's average contract value is rising rapidly (180 deals above $1M in Q4, 61 above $10M), and net dollar retention hit 139%. The transition will be as painful as the shift from on-premise software to cloud in 2010-2015. Adobe is the canonical example: when it moved from perpetual Creative Suite licences ($2,599 one-time) to Creative Cloud subscriptions ($55 per month) in 2013, the stock dropped 16% over the following year as revenue temporarily collapsed before recovering to all-time highs. The margin compression and growth slowdown will be similar, but the recovery will be selective: only companies that own proprietary data or occupy the orchestration layer will rerate. Lastly, the question that might haunt these AI companies for years to come: headcount. The deployment of Claude Cowork and OpenAI Frontier across Fortune 500 companies will reduce knowledge-worker headcount. McKinsey estimates current AI technologies could automate roughly 57% of US work hours. Goldman Sachs projects 300 million full-time jobs globally are exposed. The pace of AI adoption is racing ahead of the readiness level of these enterprises, with SaaS seat counts caught in the crossfire. (our selection of winners and losers subject to the AI-driven business model repricing) To dig further into smaller companies bound to benefit from this AI-driven business model repricing, create your own StockScreener like we did: To find out more about ETFs available to index this AI-driven business model repricing, make your own ETF Screener like we did: The transition from per-seat to fluid, outcome-based pricing will be painful, and it will take years. This structural repricing is similar in magnitude to Adobe's shift from perpetual licences to subscriptions in 2013, but with a harder edge: the business model is going to be more fluid and outcome driven to accommodate an agentic workforce, rather than the static per-seat subscription model. What propped up these stock prices until now was a unique mixture of tailwinds that has now reversed: COVID-driven forced digitalisation created an illusion of permanent demand acceleration. Low interest rates inflated the present value of future cash flows. Incumbents were massively underprepared for this AI expansion on their businesses, giving them a false sense of security. And the first wave of AI (2023-2025) was perceived as additive (more productivity per seat) rather than substitutive (fewer seats needed). That view is coming crashing down as of January 30 and February 6. The market is now repricing the entire software sector through the lens of a simple question: does your business model survive in a world where AI agents replace human workers? Companies that own the proprietary data AI needs (Thomson Reuters, RELX, Wolters Kluwer, Intuit, Experian) will emerge as winners. Companies that orchestrate AI within enterprises (Palantir, Databricks, Snowflake) will build the next generation of enterprise infrastructure. But companies that merely provide per-seat workflow tools, with no proprietary data moat and no platform lock-in, face a prolonged and painful transition that the market is only beginning to price. As Jefferies' Ron Eliasek wrote yesterday: AI will be transformational, but software companies with deep moats, trusted brands, and top talent are still positioned to thrive. We agree with the first half. The second half depends entirely on which type of software company you are talking about. It is the model (both the business model and the AI model), not the sector.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Major software companies including Salesforce, ServiceNow, and Oracle saw share prices tumble as new AI agents threaten to replace traditional business software. The market selloff, dubbed the 'SaaSpocalypse,' has investors divided on whether this represents a buying opportunity or the beginning of fundamental industry disruption that could reshape how we work.

AI Disruption Reshapes the Software Industry

The software industry faces its most significant challenge yet as AI agents from Anthropic and OpenAI threaten to fundamentally alter how businesses operate. In recent weeks, major software-as-a-service companies including Salesforce, ServiceNow, and Oracle experienced dramatic share price declines, with an exchange-traded fund tracking the US software sector dropping 22%

2

. The market selloff, which some analysts have dubbed the "SaaSpocalypse," erased nearly $1 trillion in value from enterprise software stocks3

.

Source: Market Screener

New agentic AI tools like Anthropic's Claude Cowork, OpenAI's Frontier, and open-source platforms such as OpenClaw are at the center of this upheaval

1

. These AI agents act like digital co-workers, combining automation with generative AI technology to complete complex, multi-step tasks that previously required human intervention. Nick Evans, a Polar Capital fund manager whose $12 billion global technology fund beat 99% of peers over one year, warns that "application software faces an existential threat from AI"2

.

Source: Bloomberg

Market Selloff Divides Wall Street Analysts

The threat to software sector has created an unusual split among typically bullish Wall Street analysts. Tom Lee from Fundstrat recently cautioned that "AI is wreaking havoc across software now, and that means that job losses are soon to follow"

5

. Meanwhile, Wedbush analyst Dan Ives takes the opposite view, calling the downturn "the most head scratching sell-off" and a "golden buying opportunity"5

.

Source: Motley Fool

Investors are grappling with what Morgan Stanley analysts call a "Trinity of Software Fears" that has driven down stock multiples by 33%

4

. The primary concern centers on knowledge work automation: as generative AI expands capabilities to handle unstructured data like emails and presentations, companies may need fewer employees—and therefore fewer software licenses. This threatens the traditional software business model of charging per user or "seat."AI Code Generation Changes the Competitive Landscape

The rise of AI code generation tools has lowered barriers to software development dramatically. Companies are increasingly building their own applications internally rather than purchasing expensive third-party solutions. Swedish fintech company Klarna stopped using software from Salesforce and Workday in 2024, replacing them with smaller SaaS tools and using AI coding tool Cursor to build custom applications

3

.Evans sold all his fund's holdings in application software companies including SAP, ServiceNow, Adobe, and HubSpot, stating "We won't go back to these companies"

2

. He predicts most software firms will follow the path of newspapers in the 2000s, decimated by internet disruption.Marc Andreessen's Prophecy Comes Full Circle

Fifteen years after Marc Andreessen's famous "Software Is Eating The World" essay, his prediction has materialized in an unexpected way. While software did consume retail, video, and telecommunications as Andreessen foresaw, AI is now consuming software itself

4

. Morgan Stanley analysts note that generative AI represents "a continuing expansion of what types of work and business processes software can now effectively automate."What Remains Protected in the SaaS Industry

Not all enterprise software faces equal risk. Systems-of-record that handle proprietary data like billing, compliance, and audit trails remain more defensible. Salesforce executive Madhav Thattai argues that AI agents can't replicate thousands of bespoke business rules built over years

3

. Infrastructure software companies like Cloudflare and Snowflake, which provide foundational systems, also appear less vulnerable2

.Recent results from Datadog and Fastly showed soaring demand for internet infrastructure, with Datadog shares rising over 10% and Fastly more than doubling

2

. Cybersecurity software also faces no immediate AI threat, according to Evans.Related Stories

Implications for Jobs and Workflows

The shift affects more than just software company valuations—it threatens to transform white-collar work fundamentally. Since ChatGPT's arrival in November 2022, AI tools have raised questions about the future of knowledge workers, including software engineers and lawyers

1

. Junior software engineering jobs have declined nearly 20% over three years, highlighting AI automation's impact1

.However, several factors may moderate the pace of change. Organizational transformation remains slower than technological advancement, and heavy AI reliance risks eroding human expertise and creativity

1

. Companies must also navigate complex compliance requirements that become more challenging when AI handles critical workflows.Software Companies Fight Back

Major players aren't accepting disruption passively. ServiceNow CEO Bill McDermott emphasized that his company offers hybrid pricing structures allowing either seat-based or usage-based models

5

. Salesforce attempted to lead the charge with Agentforce, its AI agent platform, though performance has been lackluster3

. ServiceNow and Figma recently announced partnerships with Anthropic, while Salesforce inked a deep partnership with OpenAI5

.Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang suggested AI will likely use existing software tools rather than building entirely new ones, potentially preserving some value for established platforms

5

. Yet questions remain about whether software companies can maintain pricing power if much of their value derives from third-party AI models. As technology evolves rapidly and investors watch closely, the software industry stands at a crossroads between existential crisis and adaptation opportunity.References