AI Music Generation: India's Beatoven.ai Leads the Way in Ethical and Creative Approach

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

India's Beatoven.ai Shows the World How AI Music Generation is Done Right

Within a year, Beatoven.ai amassed more than 100,000 data samples, which were all proprietary for them. AI music generation is a tricky business. Amidst copyright claims and the need for fairly compensating artists, it becomes an uphill task for AI startups, such as Suno.ai or Udio AI, to gain revenue and popularity. However, Beatoven.ai, an Indian AI music startup, has gotten the hang of it in the most ethical and responsible way possible. One of the most important reasons for that is its co-founder and CEO Mansoor Rahimat Khan is a professional sitar player himself and comes from a family of musicians going back seven generations. "I was very fascinated by this field of music tech," he said. Khan told AIM that he started his journey at IIT Bombay and realised that though there were not many opportunities in India, he wanted to combine his passion for music and technology. Beatoven.ai is part of the JioGenNext 2024, Google I/O 2024, and AWS ML Elevate 2023 programs. Khan said that the team applied to many accelerator programs because they realised they needed a lot of compute to fulfil the goal of building an AI music generator. The company raised $1.3 million in its pre-series A round led by Entrepreneur First and Capital 2B, with a total funding of $2.42 million. After switching several jobs, Khan met Siddharth Bhardwaj and building on their shared passions for music and tech founded Beatoven.ai in 2021. "After coming back from Georgia Tech, I got involved in the startup ecosystem, and started working with ToneTag, an audio tech startup funded by Amazon," said Khan. The co-founders found out that the biggest market was in the generation of sound tracks for Indie game developers, agencies, and production houses. "But when we look at the nitty gritty of the industry, copyrights are a very scary thing. We thought that generative AI could be a solution to this." Khan said that the idea was to figure out how users could give simple prompts and generate audio. The initial idea was to create a simple consumer focused UI where users could select a genre, mood, and duration to generate a soundtrack. But that was when the era of LLM hadn't started and NLP wasn't good enough for such tasks. "We started in 2021 before the LLM era, and our venture capital came from Entrepreneur First. We raised a million dollars in 2021 and quickly built our technology from scratch." The biggest challenge like every other AI company was the collection of data. "You either partnered with the labels that charged huge licensing fees or scraped [data]. That was the only other option. But if you did that, you would be sued," said Khan. This is where Beatoven.ai takes the edge over other products in the market. Khan and his team started contacting small, and slowly bigger artists for creating partnerships and sourcing their own data. The company had a headstart as no one was talking about this field back then. Within a year, it amassed more than 100,000 data samples, which were all proprietary for them. During the initial days, Beatoven.ai did not use Transformers. Khan said that it is one of the reasons that the quality was not that great. Later, when Diffusion models came into the picture, the team realised that it is the way forward for AI-based music generation. The company started by using different models for different purposes, this included the ChatGPT API from OpenAI. The Beatoven.ai platform also uses CLAP (Contrastive Language-Audio Pretraining), which is mostly used for video generation. Apart from this, the company uses latent diffusion models like Stability AI's Stable Audio, VAE models, and AudioLLM, for different tasks such as individual instruments within the generated music. Then the company uses an Ensemble model for mixing all these individual audios together. For inference, the company uses CPUs (instead of GPUs), which keeps it fast and optimised, while reducing costs. Khan admitted that the audio files generated by Suno.ai's have superior quality right now, but they also use Diffusion models, which makes them a little slow. "The quality is significantly better from where we started, but it's not quite there yet." Khan added that currently the speed is high because the company uses different models for different tasks. To further expand the data, Beatoven.ai started partnering with several outlets such as Rolling Stone and packaged it like a creator fund. In January 2023, it announced a $50,000 fund for Indie music as a part of the Humans of Beatoven.ai program for expanding their catalogue. This gave Beatoven.ai a lot of popularity and many artists wanted to partner with the team. Khan said that the company aims to do more licensing deals to expand music libraries. "When it comes to Indian labels though, they are not yet open to licensing deals," said Khan. Beatoven.ai's model is certified as Fairly Trained and also certified by AI for Music as an ethically trained AI model. Apart from music generation, Beatoven.ai is launching Augment, similar to ElevenLabs's voice generation model. This would allow agencies to connect to Beatoven.ai's API and train on their own data to make remixes of their own music. For the demo, Khan showed how a simple sitar tune could be turned into a hip-hop remix. "You can just use your existing content and create new songs. That's the idea," he said. Currently, Beatoven.ai is also testing a video-to-audio model using Google's Gemini, where users can upload a video and the model would understand the context and generate music based on that. Khan showed a demo to AIM where the model could also be guided using text prompts for better quality audio generation. Khan envisions that in the near future, companies such as Spotify or YouTube start open sourcing their data and offer APIs to make the AI music industry a little more open. Meanwhile, while speaking with AIM, Udio's co-founder Andrew Sanchez said, "It's enabling for people who are just up and coming, who don't yet have big professional careers, the resources, time or money to really invest in making a career. "It's enabling a whole new set of creators." This would make everyone a musician. When it comes to Beatoven.ai, he said that he aims to head in a more B2B direction as building a direct consumer app does not make sense. "I don't believe everybody wants to create music," added Khan, saying that not everyone is learning music in the world. That is why, the company is currently focused only on background music without vocals.

[2]

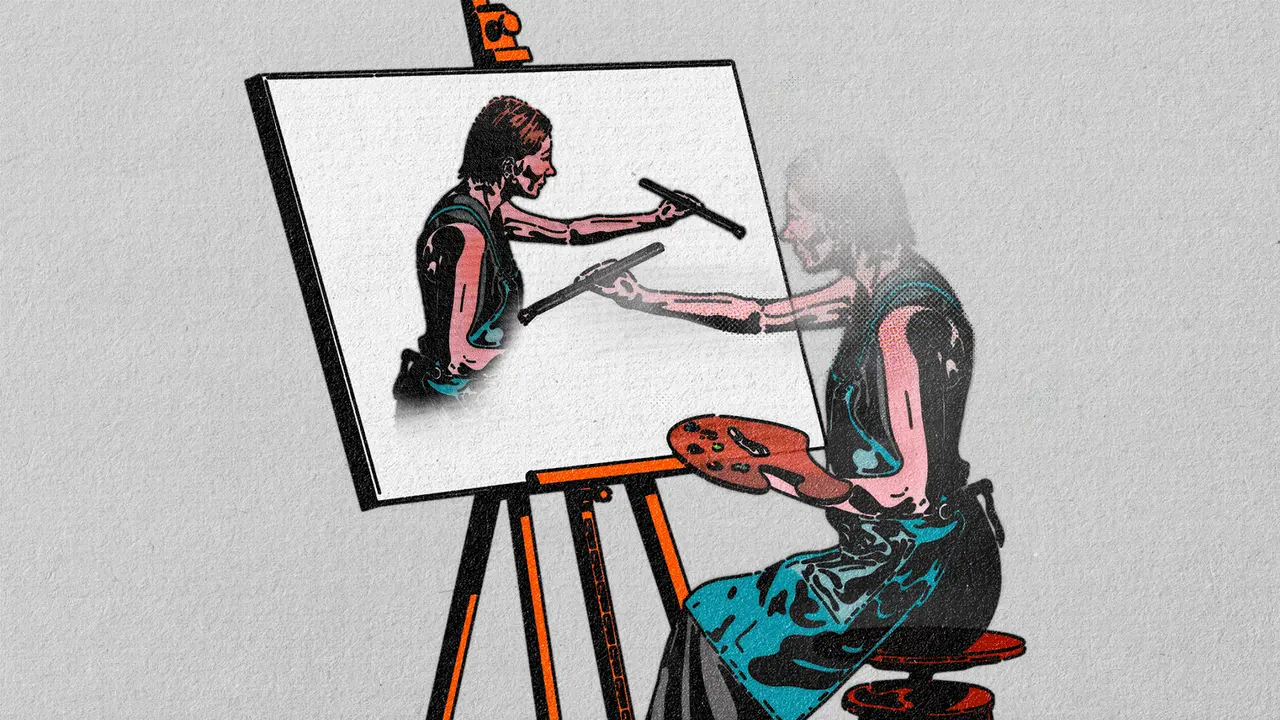

AI Needs a Speed Limit

Humans can do whatever generative AI can. They just can't do it as quickly. The first concert I bought tickets to after the pandemic subsided was a performance of the British singer-songwriter Birdy, held last April in Belgium. I've listened to Birdy more than to any other artist; her voice has pulled me through the hardest and happiest stretches of my life. I know every lyric to nearly every song in her discography, but that night Birdy's voice had the same effect as the first time I'd listened to her, through beat-up headphones connected to an iPod over a decade ago -- a physical shudder, as if a hand had reached across time and grazed me, somehow, just beneath the skin. Countless people around the world have their own version of this ineffable connection, with Taylor Swift, perhaps, or the Beatles, Bob Marley, or Metallica. My feelings about Birdy's music were powerful enough to propel me across the Atlantic, just as tens of thousands of people flocked to the Sphere to see Phish earlier this year, or some 400,000 went to Woodstock in 1969. And now tech companies are imagining a new way to cage this magic in silicon, disrupting not only the monetization and distribution of music, as they have before, but the very act of its creation. Generative AI has been unleashed on the music industry. YouTube has launched multiple AI-generated music experiments, TikTok an AI-powered song-writing assistant, and Meta an AI audio tool. Several AI start-ups, most notably Suno and Udio, offer programs that promise to conjure a piece of music in response to any prompt: Type R&B ballad about heartbreak or lo-fi coffee-shop study tune into Suno's or Udio's AI, and it will spit back convincing, if somewhat uninspired, clips complete with lyrics and a synthetic voice. "We want more people to create music, and not just consume music," David Ding, the CEO and a co-founder of Udio, told me. You may have already heard one of these synthetic tunes. Last year, an AI-generated "Drake" song went viral on Spotify, TikTok, and YouTube before being taken down; this spring, an AI-generated beat orbiting the Kendrick Lamar-Drake feud was streamed millions of times. Twenty-five years after Napster, with all that's come since then, musicians should be accustomed to technology reordering their livelihood. Many have expressed concern over the current moment, signing a letter in April warning that AI could "degrade the value of our work and prevent us from being fairly compensated for it." (Stars including Katy Perry, Nicki Minaj, and Jon Bon Jovi were among the signatories.) In June, major record labels sued Suno and Udio, alleging that their AI products had been trained on copyrighted music without permission. Read: Artists are losing the war against AI Some of these fears are misplaced. Anyone who expects that a program can create music and replace human artistry is wrong: I doubt that many people would line up for Lollapalooza to watch SZA type a prompt into a laptop, or to see a robot croon. Still, generative AI does pose a certain kind of threat to musicians -- just as it does to visual artists and authors. What is becoming clear now is that the coming war is not really one between human and machine creativity; the two will forever be incommensurable. Rather, it is a struggle over how art and human labor are valued -- and who has the power to make that appraisal. "There's a lot more to making a song than it sounding good," Rodney Alejandro, a musician and the chair of the Berklee College of Music's songwriting department, told me. Truly successful music, he said, depends on an artist's particular voice and life experience, rooted in their body, coursing through the composition and performance, and reaching a community of listeners. While AI models are starting to replicate musical patterns, it is the breaking of rules that tends to produce era-defining songs. Algorithms "are great at fulfilling expectations but not good at subverting them, but that's what often makes the best music," Eric Drott, a music-theory professor at the University of Texas at Austin, told me. Even the promise of personalized music -- a song about your breakup -- negates the cultural valence of every heartbroken person crying to the same tune. As the musician and technologist Mat Dryhurst has put it, "Pop music is a promise that you aren't listening alone." It might be more accurate to say that these programs make and arrange noise, but not music -- closer to an electric guitar or Auto-Tune than a creative partner. Musicians have always experimented with technology, even algorithms. Beginning in the 1700s, classical composers, possibly even Mozart, created sets of musical bars that could be randomly combined into various compositions by rolling dice; two centuries later, John Cage used the I-Ching, an ancient Chinese text, to randomly compose songs. Computer-modulated "generative music" was popularized three decades ago by Brian Eno. Phonographs, turntables, and streaming have all transformed how music sounds, is made, and becomes popular. Visual artists have experimented with new technologies and automation for a similarly long time. Radio didn't break music, and photography didn't break painting. "From the perspective of art, [AI] is absolutely a boring question," Amanda Wasielewski, an art-history professor at Uppsala University, in Sweden, told me. To say ChatGPT will force humans to invent new languages, or abandon language altogether, would be absurd. Audio-generation models pose no more of an existential challenge to the nature of music. Within this framework, it's easy to see how they might be useful tools. AI could help an artist who struggles with a certain instrument, isn't good at mixing and mastering, or needs help revising a lyric. Andrew Sanchez, the COO and a co-founder of Udio, told me that artists use AI to both provide "the germ of an idea" and workshop their own musical ideas, "using the AI to kind of bring something new." This is how Dryhurst and his collaborator and partner, Holly Herndon, perhaps the world's foremost AI artists and musicians, seem to use the technology. They've been experimenting with AI in their joint work for nearly a decade, using custom and corporate models to explore voice clones and push the limits of AI-generated sounds and images: synthetic voices, ways to "spawn" works in the style of other willing artists, AI models that respond to user prompts in unsettling ways. AI provides the opportunity, Herndon told me, to generate "infinite media" from a seed idea. Read: Welcome to a world without endings But even as Herndon sees AI's potential to transform the art and music ecosystem, "art is not just the media," she said. "It's the complex web of relationships and the discourse and the contexts that it's made in." Consider the prototypical example of visual art that observers scorn: a Jackson Pollock drip painting. I could do that, detractors say -- but what's relevant is that Pollock actually did. The enormous paintings are as much the tracks of Pollock's dance around the canvas, laid across the floor as he worked, as they are delightful visual images. They matter as much because of the art world they emerged from and exist in as because of how they look. What is actually terrifying and disruptive about AI technology has little to do with aesthetics or creativity. The issue is artists' lives and livelihoods. "It's actually about labor," Nick Seaver, an anthropology professor at Tufts and the author of Computing Taste: Algorithms and the Makers of Music Recommendation, told me. "It's not really about the nature of music." There is "not a chance in hell" that the next Taylor Swift hit will be AI-generated, he said, but "it's very plausible" that the next commercial jingle you hear will be. The music industry has adapted to, and blossomed after, technological threats in the past. But there is "a lot of pain and a lot of dislocation and a lot of immiseration that happens along the way," Drott told me. Musical recordings eventually allowed more people to access music and enabled new venues of creative expression, expanding the market of listeners and creating entirely new sorts of jobs for sound, recording, and mastering engineers. But before that could happen, Drott said, huge numbers of live performers lost their jobs in the early 20th century -- recordings replaced ensembles in movie theaters and musicians in many nightclubs, for instance. Sanchez, of Udio, told me that he believes generative AI will allow more people to create music, as amateurs and professionally. Even if that's true, generative AI will also eat away at the work available to people who make music for strictly commercial and production purposes, whose customers may decide that aesthetic vision is secondary to cost -- those who compose background music and clips for sample libraries, or recording engineers. At one point in our conversation, Udio's Ding likened using music-generating AI to conducting an orchestra: The user envisions the whole piece, but the AI does every part autonomously. The metaphor is beautiful, offering the possibility of playing with complex musical concepts in the same way one might play with a simple chord progression or scale at a piano. It also implies that an entire orchestra is out of work. What is different about AI is a matter of scale, not kind. Record labels are suing Udio and Suno not because they fear that the start-ups will fundamentally change music itself, but because they fear that the start-ups will change the speed at which music is made, without the permission of, or payments to, musicians whose oeuvres those tools depend on and the labels that own the legal rights to those catalogs. (Udio declined to comment on the litigation or say where its training data come from. Mikey Shulman, the CEO of Suno, told me in an emailed statement that his company's product "is designed to generate completely new outputs, not to memorize and regurgitate pre-existing content.") Humans already sample from and cover others' work, and can get in trouble if they do so without sharing credit or royalties. What AI models are being accused of, although technologically different -- reproducing likeness and style more than an exact song -- is fundamentally a similar heist carried out at unprecedented speed and scale. Herein lies the issue, really, with AI in any setting: The programs aren't necessarily doing something no human can; they're doing something no human can in such a short period of time. Sometimes that's great, as when an AI model quickly solves a scientific challenge that would have taken a researcher years. Sometimes that's terrifying, as when Suno or Udio appears capable of replacing entire production studios. Frequently, the dividing line is blurred -- for an amateur musician to be able to generate a high-quality beat or for an independent graphic designer to take on more assignments seems great. But somewhere down the line, that means a producer or another designer didn't get a contract. The key question AI raises is perhaps one of speed limits. Read: Science is becoming less human Also, unlike technological shifts in the past, the tremendous resources needed to create a cutting-edge AI model today mean the technology emerges from -- and further entrenches -- a handful of extremely well-resourced companies that are accountable to nobody but their investors. If AI replaces large numbers of working artists, that will be a triumph not of machines over human creativity but of oligopoly over civil society, and a failure of our laws and economy. Or perhaps, amid a deluge of AI-generated jingles and podcast music and pop songs, we will all search even harder for the human. When I learned, a few months after the Belgium concert, that Birdy would be performing in New York City in the fall, I immediately bought tickets for myself and my sister. Birdy performed a version of one of her songs as a ballad, which built into a cascading sequence involving a looper pedal, that gave me goose bumps. The pedal layered, or "looped," her voice over itself live -- a piece of technology that, instead of replacing humanity, amplifies it.

Share

Share

Copy Link

India's Beatoven.ai is making waves in the AI music generation industry with its innovative and ethical approach. Meanwhile, the global landscape of AI-generated music continues to evolve, raising questions about creativity and copyright.

India's Beatoven.ai: A Pioneer in Ethical AI Music Generation

In the rapidly evolving world of artificial intelligence, India's Beatoven.ai has emerged as a frontrunner in the field of AI music generation. The company, founded by Mansoor Rahimat Khan, is making waves with its innovative approach that prioritizes ethical considerations and human creativity

1

.Beatoven.ai's unique selling point is its commitment to creating original compositions rather than mimicking existing artists. The platform generates background music for content creators, ensuring that each piece is copyright-free and tailored to the user's needs. This approach not only addresses legal concerns but also promotes originality in the AI-generated music space

1

.The Global Landscape of AI Music Generation

While Beatoven.ai is making strides in India, the global AI music generation industry is experiencing rapid growth and transformation. Companies like Suno and Udio are pushing the boundaries of what's possible with AI-generated music, creating tools that allow users to produce songs complete with lyrics and vocals

2

.These advancements have sparked debates about the nature of creativity and the potential impact on human musicians. Critics argue that AI-generated music could lead to job losses and devalue human creativity. However, proponents suggest that these tools can democratize music creation and serve as powerful aids for human artists

2

.Ethical Considerations and Copyright Challenges

One of the most pressing issues in AI music generation is copyright. Many AI models are trained on existing music, raising questions about intellectual property rights. Beatoven.ai's approach of creating original compositions helps sidestep this issue, but it remains a significant concern for the industry at large

1

2

.Companies like Suno have implemented measures to prevent the direct imitation of specific artists, but the legal landscape surrounding AI-generated music remains complex and largely uncharted

2

.Related Stories

The Future of AI in Music

As AI continues to evolve, its role in music creation is likely to expand. Some experts predict that AI will become an indispensable tool for musicians, much like how digital audio workstations have become standard in modern music production

2

.However, the integration of AI into the music industry is not without challenges. Balancing technological advancement with ethical considerations, preserving human creativity, and addressing copyright concerns will be crucial as the field continues to develop

1

2

.India's Role in Shaping the Future of AI Music

With companies like Beatoven.ai leading the way, India is positioning itself as a key player in the ethical development of AI music generation. The country's approach, which emphasizes originality and respect for human creativity, could serve as a model for the global industry

1

.As the world grapples with the implications of AI in creative fields, India's contributions to the conversation and development of ethical AI music generation tools may prove invaluable in shaping the future of this exciting and controversial technology.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

Related Stories

Major Labels Embrace AI Music Platforms After Copyright Battles, Raising Artist Concerns

16 Dec 2025•Entertainment and Society

Amazon's Alexa Plus Integration with Suno AI Sparks Copyright Concerns in Music Industry

20 Mar 2025•Technology

AI Music Generation Tools Spark Debate and Disruption in the Music Industry

01 Sept 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Pentagon's Anthropic showdown exposes who controls AI guardrails in military contracts

Policy and Regulation

3

Anthropic challenges Pentagon supply chain risk label in court over AI usage restrictions

Policy and Regulation