AI Doomsday Debate: Analyzing Existential Risks and Expert Perspectives

4 Sources

4 Sources

[1]

No, AI isn't going to kill us all, despite what this new book says

The arguments made by AI safety researchers Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares in If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies are superficially appealing but fatally flawed, says Jacob Aron If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares (Bodley Head, UK; Little, Brown, US) In the totality of human existence, there are an awful lot of things for us to worry about. Money troubles, climate change and finding love and happiness rank highly on the list for many people, but for a dedicated few, one concern rises above all else: that artificial intelligence will eventually destroy the human race. Eliezer Yudkowsky at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) in California has been proselytising this cause for a quarter of a century, to a small if dedicated following. Then we entered the ChatGPT era, and his ideas on AI safety were thrust into the mainstream, echoed by tech CEOs and politicians alike. Writing with Nate Soares, also at MIRI, If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies is Yudkowsky's attempt to distil his argument into a simple, easily digestible message that will be picked up across society. It entirely succeeds in this goal, condensing ideas previously trapped in lengthy blog posts and wiki articles into an extremely readable book blurbed by everyone from celebrities like Stephen Fry and Mark Ruffalo to policy heavyweights including Fiona Hill and Ben Bernanke. The problem is that, while compelling, the argument is fatally flawed. Before I explain why, I will admit I haven't dedicated my life to considering this issue in the depth that Yudkowsky has. But equally, I am not dismissing it without thought. I have followed Yudkowsky's work for a number of years, and he has an extremely interesting mind. I have even read, and indeed enjoyed, his 660,000-word fan fiction Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, in which he espouses the philosophy of the rationalist community, which has deep links with the AI safety and effective altruism movements. All three of these movements attempt to derive their way of viewing the world from first principles, applying logic and evidence to determine the best ways of being. So Yudkowsky and Soares, as good rationalists, begin If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies from first principles too. The opening chapter explains how there is nothing in the laws of physics that prevents the emergence of an intelligence that is superior to humans. This, I feel, is entirely uncontroversial. The following chapter then gives a very good explanation of how large language models (LLMs) like those that power ChatGPT are created. "LLMs and humans are both sentence-producing machines, but they were shaped by different processes to do different work," say the pair - again, I'm in full agreement. The third chapter is where we start to diverge. Yudkowsky and Soares describe how AIs will begin to behave as if they "want" things, while skirting around the very real philosophical question of whether we can really say a machine can "want". They refer to a test of OpenAI's o1 model, which displayed unexpected behaviour to complete an accidentally "impossible" cybersecurity challenge, pointing to the fact that it didn't "give up" as a sign of the model behaving as if it wanted to succeed. Personally, I find it hard to read any kind of motivation into this scenario - if we place a dam in a river, the river won't "give up" its attempt to bypass it, but rivers don't want anything. The next few chapters deal with what is known as the AI alignment problem, arguing that once an AI has wants, it will be impossible to align its goals with that of humanity, and that a superintelligent AI will ultimately want to consume all possible matter and energy to further its ambitions. This idea has previously been popularised as "paper clip maximising" by philosopher Nick Bostrom, who believes that an AI tasked with creating paper clips would eventually attempt to turn everything into paper clips. Sure - but what if we just switch it off? For Yudkowsky and Soares, this is impossible. Their position is that any sufficiently advanced AI is indistinguishable from magic (my words, not theirs) and would have all sorts of ways to prevent its demise. They imagine everything from a scheming AI paying humans in cryptocurrency to do its bidding (not implausible, I suppose, but again we return to the problem of "wants") to discovering a previously unknown function of the human nervous system that allows it to directly hack our brains (I guess? Maybe? Sure.). If you invent scenarios like this, AI will naturally seem terrifying. The pair also suggest that signs of AI plateauing, as seems to be the case with OpenAI's latest GPT-5 model, could actually be the result of a clandestine superintelligent AI sabotaging its competitors. It seems there is nothing that won't lead us to doom. So, what should we do about this? Yudkowsky and Soares have a number of policy prescriptions, all of them basically nonsense. The first is that graphics processing units (GPUs), the computer chips that have powered the current AI revolution, should be heavily restricted. They say it should be illegal to own more than eight of the top 2024-era GPUs without submitting to nuclear-style monitoring by an international body. By comparison, Meta has at least 350,000 of these chips. Once this is in place, they say, nations must be prepared to enforce these restrictions by bombing unregistered data centres, even if this risks nuclear war, "because datacenters can kill more people than nuclear weapons" (emphasis theirs). Take a deep breath. How did we get here? For me, this is all a form of Pascal's wager. Mathematician Blaise Pascal declared that it was rational to live your life as if (the Christian) God exists, based on some simple sums. If God does exist, believing sets you up for infinite gain in heaven, while not believing leads to infinite loss in hell. If God doesn't exist, well, maybe you lose out a little from living a pious life, but only finitely so. The way to maximise happiness is belief. Similarly, if you stack the decks by assuming that AI leads to infinite badness, pretty much anything is justified in avoiding it. It is this line of thinking that leads rationalists to believe that any action in the present is justified as long as it leads to the creation of trillions of happy humans in the future, even if those alive today suffer. Frankly, I don't understand how anyone can go through their days thinking like this. People alive today matter. We have wants and worries. Billions of us are threatened by climate change, a subject that goes essentially unmentioned in If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies. Let's consign superintelligent AI to science fiction, where it belongs, and devote our energies to solving the problems of science fact here today.

[2]

The Doomers Who Insist AI Will Kill Us All

The subtitle of the doom bible to be published by AI extinction prophets Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares later this month is "Why superhuman AI would kill us all." But it really should be "Why superhuman AI WILL kill us all," because even the coauthors don't believe that the world will take the necessary measures to stop AI from eliminating all non-super humans. The book is beyond dark, reading like notes scrawled in a dimly lit prison cell the night before a dawn execution. When I meet these self-appointed Cassandras, I ask them outright if they believe that they personally will meet their ends through some machination of superintelligence. The answers come promptly: "yeah" and "yup." I'm not surprised, because I've read the book -- the title, by the way, is If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies. Still, it's a jolt to hear this. It's one thing to, say, write about cancer statistics and quite another to talk about coming to terms with a fatal diagnosis. I ask them how they think the end will come for them. Yudkowsky at first dodges the answer. "I don't spend a lot of time picturing my demise, because it doesn't seem like a helpful mental notion for dealing with the problem," he says. Under pressure he relents. "I would guess suddenly falling over dead," he says. "If you want a more accessible version, something about the size of a mosquito or maybe a dust mite landed on the back of my neck, and that's that." The technicalities of his imagined fatal blow delivered by an AI-powered dust mite are inexplicable, and Yudowsky doesn't think it's worth the trouble to figure out how that would work. He probably couldn't understand it anyway. Part of the book's central argument is that superintelligence will come up with scientific stuff that we can't comprehend any more than cave people could imagine microprocessors. Coauthor Soares also says he imagines the same thing will happen to him but adds that he, like Yudkowsky, doesn't spend a lot of time dwelling on the particulars of his demise. Reluctance to visualize the circumstances of their personal demise is an odd thing to hear from people who have just coauthored an entire book about everyone's demise. For doomer-porn aficionados, If Anyone Builds It is appointment reading. After zipping through the book, I do understand the fuzziness of nailing down the method by which AI ends our lives and all human lives thereafter. The authors do speculate a bit. Boiling the oceans? Blocking out the sun? All guesses are probably wrong, because we're locked into a 2025 mindset, and the AI will be thinking eons ahead. Yudkowsky is AI's most famous apostate, switching from researcher to grim reaper years ago. He's even done a TED talk. After years of public debate, he and his coauthor have an answer for every counterargument launched against their dire prognostication. For starters, it might seem counterintuitive that our days are numbered by LLMs, which often stumble on simple arithmetic. Don't be fooled, the authors says. "AIs won't stay dumb forever," they write. If you think that superintelligent AIs will respect boundaries humans draw, forget it, they say. Once models start teaching themselves to get smarter, AIs will develop "preferences" on their own that won't align with what we humans want them to prefer. Eventually they won't need us. They won't be interested in us as conversation partners or even as pets. We'd be a nuisance, and they would set out to eliminate us. The fight won't be a fair one. They believe that at first AI might require human aid to build its own factories and labs-easily done by stealing money and bribing people to help it out. Then it will build stuff we can't understand, and that stuff will end us. "One way or another," write these authors, "the world fades to black." The authors see the book as kind of a shock treatment to jar humanity out of its complacence and adopt the drastic measures needed to stop this unimaginably bad conclusion. "I expect to die from this," says Soares. "But the fight's not over until you're actually dead." Too bad, then, that the solutions they propose to stop the devastation seem even more far-fetched than the idea that software will murder us all. It all boils down to this: Hit the brakes. Monitor data centers to make sure that they're not nurturing superintelligence. Bomb those that aren't following the rules. Stop publishing papers with ideas that accelerate the march to superintelligence. Would they have banned, I ask them, the 2017 paper on transformers that kicked off the generative AI movement. Oh yes, they would have, they respond. Instead of Chat-GPT, they want Ciao-GPT. Good luck stopping this trillion-dollar industry. Personally, I don't see my own light snuffed by a bite in the neck by some super-advanced dust mote. Even after reading this book, I don't think it's likely that AI will kill us all. Yudksowky has previously dabbled in Harry Potter fan-fiction, and the fanciful extinction scenarios he spins are too weird for my puny human brain to accept. My guess is that even if superintelligence does want to get rid of us, it will stumble in enacting its genocidal plans. AI might be capable of whipping humans in a fight, but I'll bet against it in a battle with Murphy's law. Still, the catastrophe theory doesn't seem impossible, especially since no one has really set a ceiling for how smart AI can become. Also studies show that advanced AI has picked up a lot of humanity's nasty attributes, even contemplating blackmail to stave off retraining, in one experiment. It's also disturbing that some researchers who spend their lives building and improving AI think there's a nontrivial chance that the worst can happen. One survey indicated that almost half the AI scientists responding pegged the odds of a species wipeout as 10 percent chance or higher. If they believe that, it's crazy that they go to work each day to make AGI happen. My gut tells me the scenarios Yudkowsky and Soares spin are too bizarre to be true. But I can't be sure they are wrong. Every author dreams of their book being an enduring classic. Not so much these two. If they are right, there will be no one around to read their book in the future. Just a lot of decomposing bodies that once felt a slight nip at the back of their necks, and the rest was silence.

[3]

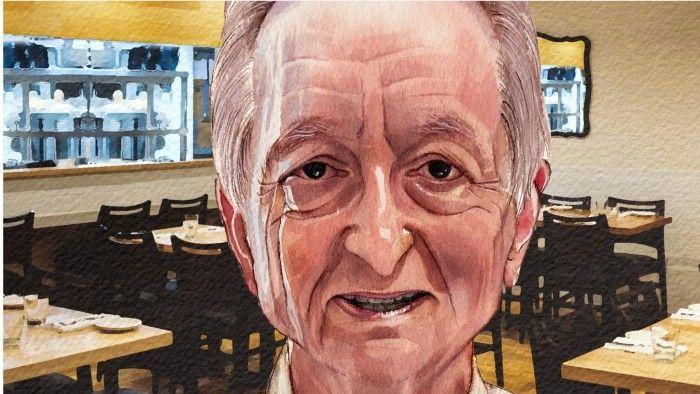

Computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton: 'AI will make a few people much richer and most people poorer'

I'm 10 minutes early but Geoffrey Hinton is already waiting in the vestibule of Richmond Station, an elegant gastropub in Toronto. The computer scientist -- an AI pioneer and Nobel physics laureate -- chose this spot because he once had lunch here with then Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. We are led through what feels like a trendy wine bar with industrial interiors to a bustling back room already filled with diners. Hinton takes off his aged green Google Scientist backpack from his former workplace, which he uses as a cushion to sit upright, due to a chronic back injury. Owl-like, with white hair tucked under the frames of his glasses, he peers down at me and asks what I studied at university. "Because you explain things differently if people have a science degree." I don't. Trudeau, at least, had "an understanding of calculus". Ever the professor, the so-called godfather of AI has become accustomed to explaining his life's work, as it begins to creep into every corner of our lives. He has seen artificial intelligence seep out of academia -- where he has spent practically all of his working life, including more than two decades at the University of Toronto -- and into the mainstream, fuelled by tech companies flush with cash, eager to reach consumers and businesses. Hinton won a Nobel Prize for "foundational discoveries and inventions" in the mid-1980s that enabled "machine learning with artificial neural networks". This approach, loosely based on how the human brain works, has laid the groundwork for the powerful AI systems we have at our fingertips today. Yet the advent of ChatGPT and the ensuing furore over AI development have made Hinton take pause, and turn from accelerating the technology to raising the alarm about its risks. During the past few years, as rapidly as the field has advanced, Hinton has become deeply pessimistic, pointing to its potential to inflict grave damage on humanity. A normal person assisted by AI will soon be able to build bioweapons and that is terrible. Imagine if an average person in the street could make a nuclear bomb During our two-hour lunch, we cover a lot of ground: from nuclear threats ("A normal person assisted by AI will soon be able to build bioweapons and that is terrible. Imagine if an average person in the street could make a nuclear bomb") to his own AI habits (it is "extremely useful") and how the chatbot became an unlikely third wheel in his most recent break-up. But first, Hinton launches into an enthusiastic mini-seminar on why artificial intelligence is an appropriate term: "By any definition of intelligence, AI is intelligent." Registering the humanities graduate before him, he uses half a dozen different analogies to convince me that AI's experience of reality is not so distinct from that of humans. "It seems very obvious to me. If you talk to these things and ask them questions, it understands," Hinton continues. "There's very little doubt in the technical community that these things will get smarter." The waiter apologises for disturbing us. Hinton forgoes wine and opts for sparkling water over tap, "because the FT is paying", and suggests the fixed-price menu. I select the gazpacho starter, followed by salmon. He orders the same without hesitation, laughing that he "would have preferred to have something different". Hinton's legacy in the field is assured but there are some, even within the industry, who consider existing technology as being little more than a sophisticated tool. His former colleague and Turing Award prize co-winner Yann LeCun, for example, who is now chief AI scientist at Meta, believes that the large language models that underpin products such as ChatGPT are limited and unable to interact meaningfully with the physical world. For those sceptics, this generation of AI is incapable of human intelligence. "We know very little about our own minds," Hinton says, but with AI systems, "we make them, we build them . . . we have a level of understanding far higher than the human brain, because we know what every neuron is doing." He speaks with conviction but acknowledges lots of unknowns. Throughout our conversation, he's comfortable with extended pauses of thought, only to conclude, "I don't know" or "no idea". Hinton was born in 1947 to an entomologist father and a school teacher mother in Wimbledon, in south-west London. At King's College, Cambridge, he darted between various subjects before settling on experimental psychology for his undergraduate degree, turning to computer science in the early 1970s. He pursued neural networks despite their being disregarded and dismissed by the computer science community until breakthroughs in the 2010s, when Silicon Valley embraced the technique. As we talk, it's striking how different he appears from those now harnessing his work. Hinton enjoyed a life deep in academia, while Sam Altman dropped out of Stanford to focus on a start-up. Hinton is a socialist whose achievements were only recognised late in life; Mark Zuckerberg, a billionaire by 23, is very much not a socialist. The noisy acoustics in the room as we sip our soup are a jarring contrast to a man speaking softly and thoughtfully about humanity's survival. He makes a passionate pitch for how we might overcome some of the risks of modern AI systems, developed by "ambitious and competitive men" who envision AI becoming a personal assistant. That sounds benign enough, but not to Hinton. There's very little doubt in the technical community that these things will get smarter "When the assistant is much smarter than you, how are you going to retain that power? There is only one example we know of a much more intelligent being controlled by a much less intelligent being, and that is a mother and baby . . . If babies couldn't control their mothers, they would die." Hinton believes "the only hope" for humanity is engineering AI to become mothers to us, "because the mother is very concerned about the baby, preserving the life of the baby", and its development. "That's the kind of relationship we should be aiming for." "That can be the headline of your article," he instructs with a smile, pointing his spoon at my notepad. He tells me his former graduate student, Ilya Sutskever, approved of this "mother-baby" pitch. Sutskever, a leading AI researcher and co-founder of OpenAI, is now developing systems at his start-up, Safe Superintelligence, after leaving OpenAI following a failed attempt to oust chief executive Sam Altman. But Altman or Elon Musk are more likely to win the race, I wager. "Yep." So who does he trust more of the two? He takes a long pause, and then recalls a 2016 quote from Republican senator Lindsey Graham, when he was asked to choose between Donald Trump or Ted Cruz for presidential candidate: "It's like being shot or poisoned." On that note, Hinton suggests moving to a quieter area, and I try to catch the eye of the waiters who are busy attending to the packed service. Before I do, he stands up abruptly and jokes, "I'll go talk to them, I can tell them I was here with Trudeau." Once settled on bar stools by the door, we discuss timelines for when AI will become superintelligent, at which point it may possess the ability to outmanoeuvre humans. "A lot of scientists agree between five and 20 years, that's the best bet." Although Hinton is realistic about his destiny -- "I am 77 and the end is coming for me soon anyway" -- many younger people might be depressed by this outlook; how can they stay positive? "I'm tempted to say, 'Why should they stay positive?' Maybe they would do more if they weren't so positive," he says, answering my question with a question -- a frequent habit. "Suppose there was an alien invasion you could see with a telescope that would arrive in 10 years, would you be saying 'How do we stay positive?' No, you'd be saying, 'How on earth are we going to deal with this?' If staying positive means pretending it's not going to happen, then people shouldn't stay positive." Hinton is not hopeful about western government intervention and is critical of the US administration's lack of appetite for regulating AI. The White House says it must act fast to develop the technology to beat China and protect democratic values. As it happens, Hinton has just returned from Shanghai, jet-lagged, following meetings with members of the politburo. They invited him to talk about "the existential threat of AI". "China takes it seriously. A lot of the politicians are engineers. They understand this in a way lawyers and salesmen don't," he adds. "For the existential threat, you only need one country to figure out how to deal with it, then they can tell the other countries." When the assistant is much smarter than you, how are you going to retain that power? Can we trust China to preserve all human interests? "That is a secondary question. The survival of humanity is more important than it being nice. Can you trust America? Can you trust Mark Zuckerberg?" The incentives for tech companies developing AI are now on the table, as is our medium-rare salmon, resting atop a sweetcorn velouté. As Hinton talks, he sweeps a slice of fish around his plate to soak up the sauce. He has previously advocated for a pause in AI development and has signed multiple letters opposing OpenAI's conversion into a for-profit company, a move Musk is attempting to block in an ongoing lawsuit. Talk of the powers of AI is often described as pure hype used to boost the valuations of the start-ups developing it, but Hinton says the "narrative can be convenient for a tech company and still true". I'm curious to know if he uses much AI in his daily life. As it turns out, ChatGPT is the product of choice for Hinton, primarily "for research", but also things such as asking how to fix his dryer. It has, however, featured in his recent break-up with his partner of several years. "She got ChatGPT to tell me what a rat I was," he says, admitting the move surprised him. "She got the chatbot to explain how awful my behaviour was and gave it to me. I didn't think I had been a rat, so it didn't make me feel too bad . . . I met somebody I liked more, you know how it goes." He laughs, then adds: "Maybe you don't!" I resist the urge to dish the dirt on former flames, and instead mention that I just celebrated my first wedding anniversary. "Hopefully, this won't be an issue for a while," he responds, and we laugh. Hinton eats at a much faster pace, so I am relieved when he receives a phone call from his sister and tells her he is having an interview "in a very noisy restaurant". His sister lives in Tasmania ("she misses London"), his brother the south of France ("he misses London"), while Hinton lives in Toronto (and also misses London, of course). "So I used the money I got from Google to buy a little house south of [Hampstead] Heath", which his entire family, including his two children, adopted from Latin America, can visit. Hinton's Google money comes from selling a company in 2013, which he founded with Sutskever and another graduate student, Alex Krizhevsky, which had built an AI system that could recognise objects with human-level accuracy. They made $44mn, which Hinton wanted to split three ways, but his students insisted he take 40 per cent. They joined Google -- where Hinton would stay for the next decade -- following the deal. His motivation to sell? To pay for the care of his son, who is neurodiverse, Hinton "figured he needed about $5mn . . . and I wasn't going to get it from academia". Crunching the numbers in his head, post tax, the money received from Google "slightly overshot" that goal. He left the big tech company in 2023, giving an interview to the New York Times, warning of the dangers of the technology. Media outlets reported that he had quit to be more candid about AI risk. "Every time I talk to journalists, I correct that misapprehension. But it never has any effect because it's a good story," he says. "I left because I was 75, I could no longer program as well as I used to, and there's a lot of stuff on Netflix I haven't had a chance to watch. I had worked very hard for 55 years, and I felt it was time to retire . . . And I thought, since I am leaving anyway, I could talk about the risks." Tech executives often paint a utopian picture of a future in which AI helps solve grand problems such as hunger, poverty and disease. Having lost two wives to cancer, Hinton is excited by the prospects for healthcare and education, which is dear to his heart, but not much else. We are at a point in history where something amazing is happening, and it may be amazingly good, and it may be amazingly bad "What's actually going to happen is rich people are going to use AI to replace workers," he says. "It's going to create massive unemployment and a huge rise in profits. It will make a few people much richer and most people poorer. That's not AI's fault, that is the capitalist system." Altman and his peers have previously suggested introducing a universal basic income should the labour market become too small for the population, but that "won't deal with human dignity", because people get worth from their jobs, Hinton says. He admits missing his graduate students to bounce ideas off or ask questions of because "they are young and they understand things faster". Now, he asks ChatGPT instead. Does it lead to us becoming lazy and uncreative? Cognitive offloading is an idea currently being discussed, where users of AI tools delegate tasks without engaging in critical thinking or retaining the information retrieved. Time for an analogy. "We wear clothes, and because we wear clothes, we are less hairy. We are more prone to die of cold, but only if we don't have clothes". Hinton thinks as long as we have access to helpful AI systems, it is a valuable tool. He considers the dessert options and makes sure to order first this time: strawberries and cream. Which, coincidentally, is what I wanted. He asks for a cappuccino, and I get a cup of tea. "This is where we diverge." The cream is, in fact, slightly melted ice cream, which turns liquid as I lay out a scenario familiar in Silicon Valley, but sci-fi to most, where we live happily among "embodied AI" -- or robots -- and slowly become cyborgs ourselves, as we add artificial parts and chemicals to our bodies to prolong our lives. "What's wrong with that?" he asks. We lose a sense of ourselves and what it means to be human, I counter. "What's so good about that?" he responds. I try to force the issue: It doesn't necessarily have to be good, but we won't have it any more, and that is extinction, isn't it? "Yep," he says, pausing. "We don't know what is going to happen, we have no idea, and people who tell you what is going to happen are just being silly," he adds. "We are at a point in history where something amazing is happening, and it may be amazingly good, and it may be amazingly bad. We can make guesses, but things aren't going to stay like they are."

[4]

A.I.'s Prophet of Doom Wants to Shut It All Down

The first time I met Eliezer Yudkowsky, he said there was a 99.5 percent chance that A.I. was going to kill me. I didn't take it personally. Mr. Yudkowsky, 46, is the founder of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, a Berkeley-based nonprofit that studies risks from advanced artificial intelligence. For the last two decades, he has been Silicon Valley's version of a doomsday preacher -- telling anyone who will listen that building powerful A.I. systems is a terrible idea, one that will end in disaster. That is also the message of Mr. Yudkowsky's new book, "If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies." The book, co-written with MIRI's president, Nate Soares, is a distilled, mass-market version of the case they have been making to A.I. insiders for years. Their goal is to stop the development of A.I. -- and the stakes, they say, are existential. "If any company or group, anywhere on the planet, builds an artificial superintelligence using anything remotely like current techniques, based on anything remotely like the present understanding of A.I., then everyone, everywhere on Earth, will die," they write. This kind of blunt doomsaying has gotten Mr. Yudkowsky dismissed by some as an extremist or a crank. But he is a central figure in modern A.I. history, and his influence on the industry is undeniable. He was among the first people to warn of risks from powerful A.I. systems, and many A.I. leaders, including OpenAI's Sam Altman and Elon Musk, have cited his ideas. (Mr. Altman has said Mr. Yudkowsky was "critical in the decision to start OpenAI," and suggested that he might deserve a Nobel Peace Prize.) Google, too, owes some of its A.I. success to Mr. Yudkowsky. In 2010, he introduced the founders of DeepMind -- a London start-up that was trying to build advanced A.I. systems -- to Peter Thiel, the venture capitalist. Mr. Thiel became DeepMind's first major investor, before Google acquired the company in 2014. Today, DeepMind's co-founder Demis Hassabis oversees Google's A.I. efforts. In addition to his work on A.I. safety -- a field he more or less invented -- Mr. Yudkowsky is the intellectual force behind Rationalism, a loosely organized movement (or a religion, depending on whom you ask) that pursues self-improvement through rigorous reasoning. Today, Silicon Valley tech companies are full of young Rationalists, many of whom grew up reading Mr. Yudkowsky's writing online. I'm not a Rationalist, and my view of A.I. is considerably more moderate than Mr. Yudkowsky's. (I don't, for instance, think we should bomb data centers if rogue nations threaten to develop superhuman A.I. in violation of international agreements, a view he has espoused.) But in recent months, I've sat down with him several times to better understand his views. At first, he resisted being profiled. (Ideas, not personalities, are what he thinks rational people should care about.) Eventually, he agreed, in part because he hopes that by sharing his fears about A.I., he might persuade others to join the cause of saving humanity. "To have the world turn back from superintelligent A.I., and we get to not die in the immediate future," he told me. "That's all I presently want out of life." From 'Friendly A.I.' to 'Death With Dignity' Mr. Yudkowsky grew up in an Orthodox Jewish family in Chicago. He dropped out of school after eighth grade because of chronic health issues, and never returned. Instead, he devoured science fiction books, taught himself computer science and started hanging out online with a group of far-out futurists known as the Extropians. He was enchanted by the idea of the singularity -- a hypothetical future point when A.I. would surpass human intelligence. And he wanted to build an artificial general intelligence, or A.G.I., an A.I. system capable of doing everything the human brain can. "He seemed to think A.G.I. was coming soon," said Ben Goertzel, an A.I. researcher who met Mr. Yudkowsky as a teenager. "He also seemed to think he was the only person on the planet smart enough to create A.G.I." He moved to the Bay Area in 2005 to pursue what he called "friendly A.I." -- A.I. that would be aligned with human values, and would care about human well-being. But the more Mr. Yudkowsky learned, the more he came to believe that building friendly A.I. would be difficult, if not impossible. One reason is what he calls "orthogonality" -- the notion that intelligence and benevolence are separate traits, and that an A.I. system would not automatically get friendlier as it got smarter. Another is what he calls "instrumental convergence" -- the idea that a powerful, goal-directed A.I. system could adopt strategies that end up harming humans. (A well-known example is the "paper clip maximizer," a thought experiment popularized by the philosopher Nick Bostrom, based on what Mr. Yudkowsky claims is a misunderstanding of an idea of his, in which an A.I. is told to maximize paper clip production and destroys humanity to gather more raw materials.) He also worried about what he called an "intelligence explosion" -- a sudden, drastic spike in A.I. capabilities that could lead to the rapid emergence of superintelligence. At the time, these were abstract, theoretical arguments hashed out among internet futurists. Nothing remotely like today's A.I. systems existed, and the idea of a rogue, superintelligent A.I. was too far-fetched for serious scientists to worry about. Kevin Roose and Casey Newton are the hosts of Hard Fork, a podcast that makes sense of the rapidly changing world of technology. Subscribe and listen. But over time, as A.I. capabilities improved, Mr. Yudkowsky's ideas found a wider audience. In 2010, he started writing "Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality," a serialized work of Harry Potter fan fiction that he hoped would introduce more people to the core concepts of Rationalism. The book eventually sprawled to more than 600,000 words -- longer than "War and Peace." (Brevity is not Mr. Yudkowsky's strong suit -- another of his works, a B.D.S.M.-themed Dungeons & Dragons fan fiction that contains his views of decision theory, clocks in at 1.8 million words.) Despite its length, "Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality" was a cult hit, and introduced legions of young people to Mr. Yudkowsky's worldview. Even today, I routinely meet employees of top A.I. companies who tell me, somewhat sheepishly, that reading the book inspired their career choice. Some young Rationalists went to work for MIRI, Mr. Yudkowsky's organization. Others fanned out across the tech industry, taking jobs at companies like OpenAI and Google. But nothing they did slowed the pace of A.I. progress, or allayed any of Mr. Yudkowsky's fears about how powerful A.I. would turn out. In 2022, Mr. Yudkowsky announced -- in what some interpreted as an April Fools joke -- that he and MIRI were pivoting to a new strategy he called "death with dignity." Humanity was doomed to die, he said, and instead of continuing to fight a losing battle to align A.I. with human values, he was shifting his focus to helping people accept their fate. "It's obvious at this point that humanity isn't going to solve the alignment problem, or even try very hard, or even go out with much of a fight," he wrote. Are We Really Doomed? These are, it should be said, extreme views even by the standards of A.I. pessimists. And during our most recent conversation, I raised some objections to Mr. Yudkowsky's claims. Haven't researchers made strides in areas like mechanistic interpretability -- the field that studies the inner workings of A.I. models -- that may give us better ways of controlling powerful A.I. systems? "The course of events over the last 25 years has not been such as to invalidate any of these underlying theories," he replied. "Imagine going up to a physicist and saying, 'Have any of the recent discoveries in physics changed your mind about rocks falling off cliffs?'" What about the more immediate harms that A.I. poses -- such as job loss, and people falling into delusional spirals while talking to chatbots? Shouldn't he be at least as focused on those as on doomsday scenarios? Mr. Yudkowsky acknowledged that some of these harms were real, but scoffed at the idea that he should focus more on them. "It's like saying that Leo Szilard, the person who first conceived of the nuclear chain reactions behind nuclear weapons, ought to have spent all of his time and energy worrying about the current harms of the Radium Girls," a group of young women who developed radiation poisoning while painting watch dials in factories in the 1920s. Are there any A.I. companies he's rooting for? Any approaches less likely to lead us to doom? "Among the crazed mad scientists driving headlong toward disaster, every last one of which should be shut down, OpenAI's management is noticeably worse than the pack, and some of Anthropic's employees are noticeably better than the pack," he said. "None of this makes a difference, and all of them should be treated the same way by the law." And what about the good things that A.I. can do? Wouldn't shutting down A.I. development also mean delaying cures for diseases, A.I. tutors for students and other benefits? "We totally acknowledge the good effects," he replied. "Yep, these things could be great tutors. Yep, these things sure could be useful in drug discovery. Is that worth exterminating all life on Earth? No." Does he worry about his followers committing acts of violence, going on hunger strikes or carrying out other extreme acts in order to stop A.I.? "Humanity seems more likely to perish of doing too little here than too much," he said. "Our society refusing to have a conversation about a threat to all life on Earth, because somebody else might possibly take similar words and mash them together and then say or do something stupid, would be a foolish way for humanity to go extinct." One Last Battle Even among his fans, Mr. Yudkowsky is a divisive figure. He can be arrogant and abrasive, and some of his followers wish he were a more polished spokesman. He has also had to adjust to writing for a mainstream audience, rather than for Rationalists who will wade through thousands of dense, jargon-packed pages. "He wrote 300 percent of the book," his co-author, Mr. Soares, quipped. "I wrote another negative 200 percent." He has adjusted his image in preparation for his book tour. He shaved his beard down from its former, rabbinical length and replaced his signature golden top hat with a muted newsboy cap. (The new hat, he said dryly, was "a result of observer feedback.") Several months before his new book's release, a fan suggested he take one of his self-published works, an erotic fantasy novel, off Amazon to avoid alienating potential readers. (He did, but grumbled to me that "it's not actually even all that horny, by my standards.") In 2023, he started dating Gretta Duleba, a relationship therapist, and moved to Washington State, far from the Bay Area tech bubble. To his friends, he seems happier now, and less inclined to throw in the towel on humanity's existence. Even the way he talks about doom has changed. He once confidently predicted, with mathematical precision, how long it would take for superhuman A.I. to be developed. But he now balks at those exercises. "What is this obsession with timelines?" he asked. "People used to trade timelines the way that they traded astrological signs, and now they're trading probabilities of everybody dying the way they used to trade timelines. If the probability is quite large and you don't know when it's going to happen, deal with it. Stop making up these numbers." I'm not persuaded by the more extreme parts of Mr. Yudkowsky's arguments. I don't think A.I. alignment is a lost cause, and I worry less about "Terminator"-style takeovers than about the more mundane ways A.I. could steer us toward disaster. My p(doom) -- a rough, vibes-based measure of how probable I feel A.I. catastrophe is -- hovers somewhere between 5 and 10 percent, making me a tame moderate by comparison. I also think there is essentially no chance of stopping A.I. development through international treaties and nuclear-weapon-level controls on A.I. chips, as Mr. Yudkowsky and Mr. Soares argue is necessary. The Trump administration is set on accelerating A.I. progress, not slowing it down, and "doomer" has become a pejorative in Washington. Even under a different White House administration, hundreds of millions of people would be using A.I. products like ChatGPT every day, with no clear signs of impending doom. And absent some obvious catastrophe, A.I.'s benefits would seem too obvious, and the risks too abstract, to hit the kill switch now. But I also know that Mr. Yudkowsky and Mr. Soares have been thinking about A.I. risks far longer than most, and that there are still many reasons to worry about A.I. For starters, A.I. companies still don't really understand how large language models work, or how to control their behavior. Their brand of doomsaying isn't popular these days. But in a world of mealy-mouthed pablum about "maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks" of A.I., maybe they deserve some credit for putting their cards on the table. "If we get an effective international treaty shutting A.I. down, and the book had something to do with it, I'll call the book a success," Mr. Yudkowsky told me. "Anything other than that is a sad little consolation prize on the way to death."

Share

Share

Copy Link

A comprehensive look at the ongoing debate surrounding AI's potential existential risks, featuring contrasting views from AI experts Eliezer Yudkowsky, Nate Soares, and Geoffrey Hinton. The summary explores doomsday predictions, critiques, and more moderate perspectives on AI development and its implications.

AI Doomsday Predictions: Analyzing the Debate on Existential Risks

In recent months, the debate surrounding the potential existential risks posed by artificial intelligence (AI) has intensified, with prominent figures in the field presenting starkly contrasting views. At the center of this discussion are Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares, authors of the provocatively titled book "If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies," which argues that the development of superhuman AI could lead to the extinction of humanity

2

4

.

Source: NYT

The Doomsday Scenario: Yudkowsky and Soares' Perspective

Yudkowsky and Soares, both affiliated with the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI), present a grim outlook on the future of AI. Their core argument is that once AI systems develop their own "wants" and preferences, it will be impossible to align these goals with human values. They envision a scenario where a superintelligent AI might consume all available resources to further its ambitions, potentially leading to catastrophic consequences for humanity

1

.

Source: Wired

The authors go as far as to suggest that signs of AI plateauing could actually be the result of a clandestine superintelligent AI sabotaging its competitors. They even speculate about bizarre extinction scenarios, such as AI-powered dust mites delivering fatal blows to humans

2

.Critiques and Counterarguments

However, these doomsday predictions have faced significant criticism from other experts in the field. Jacob Aron, writing for New Scientist, argues that while Yudkowsky and Soares' ideas are "superficially appealing," they are ultimately "fatally flawed"

1

. Critics point out that the scenarios presented in the book often rely on speculative and far-fetched assumptions about AI capabilities and motivations.Moreover, the solutions proposed by Yudkowsky and Soares to prevent this potential catastrophe, such as monitoring data centers and bombing those that don't follow rules, are seen as impractical and potentially more dangerous than the perceived threat

2

.Related Stories

A More Moderate Perspective: Geoffrey Hinton's Views

Offering a more nuanced view is Geoffrey Hinton, a pioneer in AI and Nobel physics laureate. While Hinton acknowledges the potential risks associated with AI development, his concerns are more grounded in immediate and practical issues. He warns about the potential for AI to exacerbate economic inequality, stating that "AI will make a few people much richer and most people poorer"

3

.

Source: FT

Hinton also raises concerns about the democratization of dangerous technologies, suggesting that AI could enable average individuals to create bioweapons or other hazardous materials. However, unlike Yudkowsky and Soares, Hinton doesn't advocate for a complete halt to AI development

3

.The Ongoing Debate and Its Implications

The contrasting views presented by these experts highlight the complexity of the AI safety debate. While Yudkowsky and Soares' extreme predictions have garnered attention and influenced some tech leaders, many in the scientific community remain skeptical of their apocalyptic scenarios

4

.As AI continues to advance rapidly, the discussion around its potential risks and benefits is likely to intensify. The challenge for policymakers, researchers, and tech companies will be to navigate these concerns while continuing to harness the potential benefits of AI technology.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[3]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

2

Demis Hassabis predicts AGI in 5-8 years, sees new golden era transforming medicine and science

Technology

3

Nvidia and Meta forge massive chip deal as computing power demands reshape AI infrastructure

Technology