Demis Hassabis: AI's Rapid Progress and Potential to Revolutionize Society

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Demis Hassabis on our AI future: 'It'll be 10 times bigger than the Industrial Revolution - and maybe 10 times faster'

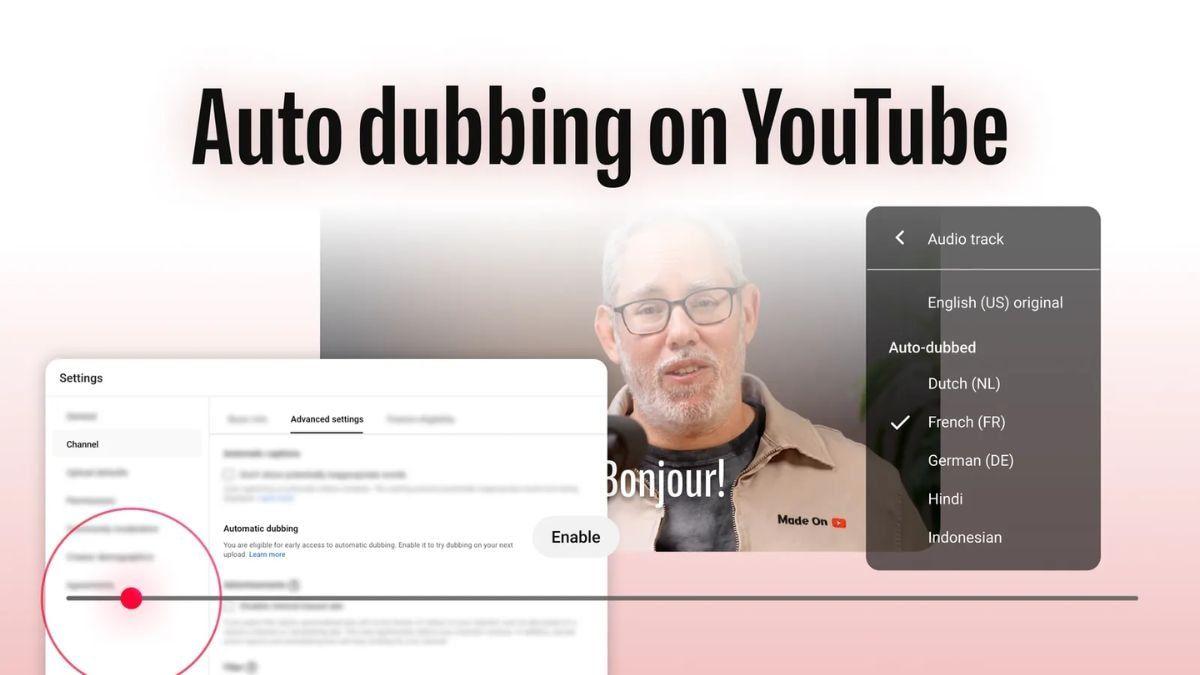

The head of Google's DeepMind says artificial intelligence could usher in an era of 'incredible productivity' and 'radical abundance'. But who will it benefit? And why does he wish the tech giants had moved more slowly? If you have a mental image of a Nobel prizewinner, Demis Hassabis probably doesn't fit it. Relatively young (he's 49), mixed race (his father is Greek-Cypriot, his mother Chinese-Singaporean), state-educated, he didn't exactly look out of place receiving his medal from the king of Sweden in December, amid a sea of grey-haired men, but it was "very surreal", he admits. "I'm really bad at enjoying the moment. I've won prizes in the past, and I'm always thinking , 'What's the next thing?' But this one was really special. It's something you dream about as a kid." Well, maybe not you, but certainly him. Hassabis was marked out as exceptional from a young age - he was a chess prodigy when he was four. Today, arguably, he's one of the most important people in the world. As head of Google DeepMind, the tech giant's artificial intelligence arm, he's driving, if not necessarily steering, what promises to be the most significant technological revolution of our lifetimes. As such, Hassabis finds himself in the position of being both a booster for AI and an apologist for it. The Nobel prize in chemistry was proof of the benefits AI can bring: DeepMind's AlphaFold database was able to predict the hitherto-unfathomable structures of proteins, the building blocks of life - a breakthrough that could lead to myriad medical advances. At the same time, fears are ever growing about the AI future that Google is helping to usher in. Being an AI ambassador is the part Hassabis didn't dream about. "If I'd had my way, we would have left it in the lab for longer and done more things like AlphaFold, maybe cured cancer or something like that," he says. "But it is what it is, and there's some benefits to that. It's great that everyone gets to play around with the latest AI and feel for themselves what it's like. That's useful for society, actually, to kind of normalise it and adapt to it, and for governments to be discussing it ... I guess I have to speak up on, especially, the scientific side of how we should approach this, and think about the unknowns and how we can make them less unknown." In person Hassabis is a mix of down-to-earth approachability and polished professionalism. Trim and well groomed, dressed entirely in black, he wears two watches: one a smart watch, the other an analogue dress watch (smart but not too flashy). He gives the impression of someone in a hurry. We're speaking in his office at DeepMind's London headquarters. On the walls outside are signed chess boards from greats such as Garry Kasparov, Magnus Carlsen and Judit Polgár. He still plays; there's a board set up on a table nearby. It was the chess that started Hassabis down the path of thinking about thinking. Between the ages of four and 13 he played competitively in England junior teams. "When you do that at such a young age, it's very formative for the way your brain works. A lot of the way I think is influenced by strategic thinking from chess, and dealing with pressure." On paper there's little else about Hassabis's background that foretold his future. His family are more on the arty side: "My dad's just finished composing a musical play in his retirement, which he staged at an arthouse theatre in north London. My sister's a composer, so I'm kind of the outlier of the family." They weren't poor, but not super-wealthy. He moved between various state schools in north London, and was homeschooled for a few years. He was also a bit of an outsider at school, he says, but he seems to have known exactly where he was going. His childhood heroes were scientific pioneers such as Alan Turing and Richard Feynman. He spent his chess winnings on early home computers such as the Sinclair ZX Spectrum and a Commodore Amiga, and learned to code. "There were few people that were interested in computers in the late 80s. There was a group of us that used to hack around, making games and other stuff, and then that became my next career after chess." In the 90s, the games industry was already working with AI. When he was 17, he coded the hit game Theme Park, in which players had to build a virtual amusement park. "The game reacted to how you were playing it," he says. Put a food stall too close to the rollercoaster exit and your virtual punters would start throwing up. After studying computer science at the University of Cambridge, then a PhD at University College London in neuroscience, he set up DeepMind in 2010 with Shane Legg, a fellow postdoctoral neuroscientist, and Mustafa Suleyman, a former schoolmate and a friend of his younger brother. The mission was straightforward, Hassabis says: "Solve intelligence and then use it to solve everything else." DeepMind soon caught Silicon Valley's attention. In 2014 the team showed off an AI that learned to master Atari video games such as Breakout, without any prior knowledge. Interest started to come from now-familiar tech players, including Peter Thiel (who was an early DeepMind investor), Google, Facebook and Elon Musk. Hassabis first met Musk in 2012. Over lunch at Space X's factory in California, Musk told Hassabis his priority was getting to Mars "as a backup planet, in case something went wrong here. I don't think he'd thought much about AI at that point." Hassabis pointed out the flaw in his plan. "I said, 'What if AI was the thing that went wrong? Then being on Mars wouldn't help you, because if we got there, it would obviously be easy for an AI to get there, through our communication systems or whatever it was.' He just hadn't thought about that. So he sat there for a minute without saying anything, just sort of thinking, 'Hmm, that's probably true.'" Shortly after, Musk, too, became an investor in DeepMind. In 2014, Google bought the company for £400m (as a result, Musk and Thiel switched to backing the rival startup OpenAI). It wasn't just access to cash and hardware that convinced them to go with Google. Founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin were computer scientists like him, and "saw Google as ultimately an AI company", says Hassabis. He also used products such as Gmail and Maps. "And finally, I just thought that the mission of Google, which is to organise the world's information, is a cool mission." From his office window, we can see the vast beige bulk of Google's just-about-finished new office, where DeepMind will be moving next year. It's fair to say the reason the tech giant is putting so much into Britain is because of Hassabis, who insisted on staying in London. "Our first backers were like, 'You've got to move to San Francisco,' but I wanted to prove it was possible here," he says. "I knew there was untapped talent around. And I knew, if we were successful, how important [AI] would be for the world, so I felt it was important to have a global approach to it, and, not just, you know, 100 square miles of Silicon Valley. I still believe that's important." In 2016, DeepMind again caught the tech world's attention when its AI defeated one of the world's best players of Go - a board game considerably more complex than chess. The AlphaFold breakthrough on protein structures was another leap forward: DeepMind has now solved the structures of over 200m proteins and made the resource publicly available. But the AI landscape shifted seismically in 2020 with the release of OpenAI's ChatGPT3, which captured the public imagination with its uncanny ability to tackle a host of problems - from strategy planning to writing poetry. ChatGPT caught big tech off guard, especially Google. "They really went for scaling, almost in a bet-the-house sort of way, which is impressive, and maybe you have to do that as a startup," says Hassabis. "We all had systems that are very similar, the leading labs, but we could see the flaws in it, like it would hallucinate sometimes. I don't think anyone fully understood, including OpenAI, that there would be these amazing use cases for it, and people would get a lot of value out of them. So that's an interesting lesson for us about how you can be a bit too close to your own technology." The race is now on. DeepMind has become "the engine room of Google", as Hassabis puts it, and AI is being built into every corner of its business: AI search summaries; smart assistant Gemini (Google's answer to ChatGPT); an AI image generator (that can add in sound effects); AI-powered smart glasses, translation tools, shopping assistants. How much the public really craves this AI-enhanced world remains to be seen. Competitors are also raising their game. Mark Zuckerberg's Meta, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and others are investing heavily, and poaching talent from their rivals. Zuckerberg is offering $100m salaries for top researchers. Suleyman, who left DeepMind in 2019, is now head of Microsoft AI, which recently poached more than 20 engineers from DeepMind. He hesitates to call his former friend a rival: "We do very different things. I think he's more on the commercial applied side; we're still focused more on that frontier research side." That frontier to be reached is surely AGI - "artificial general intelligence" - the pivotal point at which AI matches human intelligence. "I don't know if it will be a single moment. It may be a gradual thing that happens," he says, "but we'll have something that we could sort of reasonably call AGI, that exhibits all the cognitive capabilities humans have, maybe in the next five to 10 years, possibly the lower end of that." In other words, we are in the final few years of pre-AGI civilisation, after which nothing may ever be the same again. To some the prospect is apocalyptic, to others, like Hassabis, it's utopian. "Assuming we steward it safely and responsibly into the world, and obviously we're trying to play our part in that, then we should be in a world of what I sometimes call radical abundance," says Hassabis. He paints a picture of medical advances, room-temperature superconductors, nuclear fusion, advances in materials, mathematics. "It should lead to incredible productivity and therefore prosperity for society. Of course, we've got to make sure it gets distributed fairly, but that's more of a political question. And if it is, we should be in an amazing world of abundance for maybe the first time in human history, where things don't have to be zero sum. And if that works, we should be travelling to the stars, really." Is he getting too close to his own technology? There are so many issues around AI, it's difficult to know where to even begin: deepfakes and misinformation; replacement of human jobs; vast energy consumption; use of copyright material, or simply AI deciding that we humans are expendable and taking matters into its own hands. To pick one issue, the amount of water and electricity that future AI datacentres are predicted to require is astronomical, especially when the world is facing drought and a climate crisis. By the time AI cracks nuclear fusion, we may not have a planet left. "There's lots of ways of fixing that," Hassabis replies. "Yes, the energy required is going to be a lot for AI systems, but the amount we're going to get back, even just narrowly for climate [solutions] from these models, it's going to far outweigh the energy costs." There's also the worry that "radical abundance" is another way of framing "mass unemployment": AI is already replacing human jobs. When we "never need to work again" - as many have promised - doesn't that really mean we're surrendering our economic power to whoever controls the AI? "That's going to be one of the biggest things we're gonna have to figure out," he acknowledges. "Let's say we get radical abundance, and we distribute that in a good way, what happens next?" Hassabis has two sons in their late teens (his Italian-born wife is a molecular biologist). What does he envisage for their future? "It's a bit like the era I was growing up in, where home computers were coming online. Obviously it's going to be bigger than that, but you've got to embrace the new technology ... If you become an expert, kind of a ninja, at using these things, it's going to really empower the people that are good at these tools." Non-ninjas will still have a place, however: "We need some great philosophers, but also economists to think about what the world should look like when something like this comes along. What is purpose? What is meaning?" He points out that there are many things we do that aren't strictly for utility: sports, meditation, arts. "We're going to lean into those areas, as a society, even more heavily, because we'll have the time and the resources to do so." It's difficult to see Hassabis himself carving out much of that time, between DeepMind, his drug discovery company Isomorphic Labs and his endless public appearances - the list goes on. "I don't have much time that isn't working, seven days a week," he acknowledges. "I spend time with my kids playing games, board games, and that's some of my most fun times." He doesn't let them win, he says. "We play very competitively." He's also a season ticket holder at Liverpool FC and makes it to "six, seven games a year". He still plays chess online - "It's a bit like going to the gym, for the mind." And he's a mean poker player, apparently. The night after winning his Nobel prize he celebrated with a poker night with Magnus Carlsen and some world poker champions. "In another universe, I might have been a professional gamer." So, no fears about the future? "I'm a cautious optimist," he says. "So overall, if we're given the time, I believe in human ingenuity. I think we'll get this right. I think also, humans are infinitely adaptable. I mean, look where we are today. Our brains were evolved for a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and we're in modern civilisation. The difference here is, it's going to be 10 times bigger than the Industrial Revolution, and maybe 10 times faster." The Industrial Revolution was not plain sailing for everyone, he admits, "but we wouldn't wish it hadn't happened. Obviously, we should try to minimise that disruption, but there is going to be change - hopefully for the better."

[2]

Artificial intelligence could end disease, lead to "radical abundance," Google DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis says

This is an updated version of a story first published on April 20, 2025. The original video can be viewed here. When Demis Hassabis won the Nobel Prize last year, he celebrated by playing poker with a world champion of chess. Hassabis loves a game, which is how he became a pioneer of artificial intelligence. The 49-year-old British scientist is co-founder and CEO of Google's AI powerhouse, called DeepMind. We met two years ago when chatbots announced a new age. Now, as we first told you this past spring, Hassabis and others are chasing what's called artificial general intelligence -- a silicon intellect as versatile as a human but with superhuman speed and knowledge. After his Nobel and a knighthood from King Charles, we hurried back to London to see what's next from a genius who may hold the cards of our future. Demis Hassabis: What's always guided me and-- the passion I've always had is understanding the world around us. I've always been-- since I was a kid, fascinated by the biggest questions. You know, the-- meaning of-- of life, the-- nature of consciousness, the nature of reality itself. I've loved reading about all the great scientists who worked on these problems and the philosophers, and I wanted to see if we could advance human knowledge. And for me, my expression of doing that was to build what I think is the ultimate tool for advancing human knowledge, which is-- which is AI. Scott Pelley: We sat down in this room two years ago. And I wonder if AI is moving faster today than you imagined. Demis Hassabis: It's moving incredibly fast. I think we are on some kind of exponential curve of improvement. Of course, the success of the field in the last few years has attracted even more attention, more resources, more talent. So that's adding to the to this exponential progress. Scott Pelley: Exponential curve, in other words straight up? Demis Hassabis: Yep, straight up and increasing speed of progress. ...in an artificial companion that can see and hear and chat about anything. Early chatbots learned only the internet, an app called Astra also takes in the world. Scott Pelley: Do we call her she? Bibo Xu: Um, that's a good question. I'm not sure, I'm not sure we all know the answer yet... Bibo Xu, is product manager for Project Astra, an app in a new generation of chatbots that interpret the world with their own eyes. We challenged Astra with virtual paintings we chose and showed to Astra for the first time. Scott Pelley:That painting is "Automat" by Edward Hopper. Scott Pelley: The person in the painting, what emotion is she exhibiting? Astra: The subject in the painting appears pensive and contemplative, her expression suggesting a sense of solitude. Scott Pelley: Can you create a story around this picture? Astra: It's a chilly evening in the city. A Tuesday, perhaps. The woman, perhaps named Eleanor, sits alone in the diner. She is feeling melancholy due to the uncertainty of her future, and the weight of unfulfilled dreams.The scene freezes in time. Only the flow of ideas moving onward. That line, "only the flow of ideas moving onward?" I wish I'd written that. And did we hear a limit to Astra's patience? Scott Pelley: What was that fictional conversation about? Astra: Ahhh, in the story I imagined, Eleanor and her friend talked about their shared dreams and the challenges of pursuing them. Scott Pelley: Something about the way you said "Ahh" made me wonder if you were getting bored. Astra: I apologize if my tone came across that way. My aim is always to engage thoughtfully. Scott Pelley: And she said, "Well, I'm sorry if you don't like my tone." Demis Hassabis: Well, that's interesting. That's, again a challenge with these systems. As they act in the moment with the context that's around them. And that may have never been tested before. He's often surprised because AI programs are sent out on the internet to learn for themselves. They can return later with unexpected skills. Demis Hassabis: So we have theories about what kinds of capabilities these systems will have. That's obviously what we try to build into the architectures. But at the end of the day, how it learns what it picks up from the data is part of the training of these systems. We don't program that in. It learns like a human being would learn. So new capabilities or properties can emerge from that training situation. Scott Pelley: You understand how that would worry people? Demis Hassabis: Of course. It's the duality of these types of systems, that they're able to do incredible things, go beyond the things that we're able to design ourselves or understand ourselves. But, of course, the challenge is, is making sure that the knowledge databases they create we understand what's in them. Now DeepMind is training its AI model called Gemini to not just reveal the world but to act in it like booking tickets and shopping online. It's a step toward "AGI" artificial general intelligence -- with the versatility of a human mind. Scott Pelley: On track for AGI in-- Demis Hassabis: In the next five to ten years, I think. Scott Pelley: And in 2030 you will have what? Demis Hassabis: Well, we'll have a system that-- really understands everything around you in very-- nuanced and deep ways-- and are kind of embedded in your everyday life. 'Embedded' like Astra in eyeglasses. Scott Pelley: What can you tell me about this building I'm looking at? Astra: This is the Coal Drops Yard, a shopping and dining district. She sees what I see. There's a speaker in the earpiece only I can hear. Scott Pelley: What was it originally before it became shops? Astra: The Coal Drops Yard was originally a set of Victorian coal warehouses used to receive and distribute coal across London. Scott Pelley: Was coal ever a problem for the environment in London? Astra: Yes. Coal was a significant source of air pollution in London, particularly during the Industrial Revolution. It occurred to us that the only thing we contributed to this relationship--were legs -- which will also soon be engineered. Demis Hassabis: I also think another big area will be robotics. I think it will have a breakthrough moment in the next couple of years where we'll have demonstrations of maybe humanoid robots or other types of robots that can start really doing useful things. For example, researchers Alex Lee and Giulia Vezzani showed us a robot that understands what it sees... Alex Lee: Put the blocks whose color is the combination of yellow and blue into the matching color bowl. Scott Pelley: The combination of yellow and blue Scott Pelley: ...is green. And it figured that out. It's reasoning. Giulia Vezzani: Yes, definitely, yes. The toys of Demis Hassabis's childhood weren't blocks but chess pieces. At 12, he was the number two champion in the world for his age. This passion led to computer chess, video games and, finally, thinking machines. He was born to a Greek Cypriot father and Singaporean mother. Cambridge, MIT, Harvard-- he's a computer scientist with a PhD in neuroscience because, he reasoned, he had to understand the human brain first. Scott Pelley: Are you working on a system today that would be self-aware? Demis Hassabis: I don't think any of today's systems to me feel self-aware or, you know, conscious in any way. Obviously, everyone needs to make their own decisions by interacting with these chatbots. I think theoretically it's possible. Scott Pelley: But is self-awareness a goal of yours? Demis Hassabis: Not explicitly. But it may happen implicitly. These systems might acquire some feeling of self-awareness. That is possible. I think it's important for these systems to understand you, self and other. And that's probably the beginning of something like self-awareness. But, he says, if a machine becomes self-aware, we may not recognize it. Demis Hassabis: I think there's two reasons we regard each other as conscious. One is that you're exhibiting the behavior of a conscious being very similar to my behavior. But the second thing is you're running on the same substrate. We're made of the same carbon matter with our squishy brains. Now obviously with machines, they're running on silicon. So even if they exhibit the same behaviors, and even if they say the same things, it doesn't necessarily mean that this sensation of consciousness that we have is the same thing they will have. Scott Pelley: Has an AI engine ever asked a question that was unanticipated? Demis Hassabis: Not so far that I've experienced, and I think that's getting at the idea of what's still missing from these systems. They still can't really yet go beyond asking a new novel question or a new novel conjecture or coming up with a new hypothesis that has not been thought of before. Scott Pelley: They don't have curiosity? Demis Hassabis: No, they don't have curiosity, and they're probably lacking a little bit in what we would call imagination and intuition. But they will have greater imagination, he says, and soon. Demis Hassabis: I think actually in the next maybe five to ten years. I think we'll have systems that are capable of not only solving an important problem or conjecture in science but coming up with it in the first place. 'Solving an important problem' won Hassabis a Nobel Prize last year. He and colleague John Jumper created an AI model that deciphered the structure of proteins. Demis Hassabis: Proteins are the basic building blocks of life. So, everything in biology, everything in your body depends on proteins. You know, your neurons firing, your muscle fibers twitching, it's all mediated by proteins. But 3D protein structures like this are so complex, less than 1% were known. Mapping each one used to take years. DeepMind's AI model did 200 million in one year. Now Hassabis has AI blazing through solutions to drug development. Demis Hassabis: So on average, it takes, you know, ten years and billions of dollars to design just one drug. We can maybe reduce that down from years to maybe months or maybe even weeks. Which sounds incredible today but that's also what people used to think about protein structures. And it would revolutionize human health, and I think one day maybe we can cure all disease with the help of AI. Scott Pelley: The end of disease? Demis Hassabis: I think that's within reach. Maybe within the next decade or so, I don't see why not. Demis Hassabis told us AI could lead to what he calls "radical abundance" -- the elimination of scarcity. But he also worries about risk. Demis Hassabis: There's two worries that I worry about. One is that bad actors, humans you know, users of these systems repurpose these systems for harmful ends. And then the second thing is the AI systems themselves as they become more autonomous and more powerful. Can we make sure that-- we can keep control of the systems? That they're aligned with our values, they-- they're doing what we want that benefits society. And they stay on guardrails. "Guardrails" are safety limits built into the system. Scott Pelley: And I wonder if the race for AI dominance is a race to the bottom for safety. Demis Hassabis: So that's one of my big worries actually, is the-- of course all of this energy, and racing, and resources is great for progress. But it might incentivize certain actors in-- in that to cut corners. And one of the corners that could be shortcut would be safety and responsibility. So the question is, is how can we-- coordinate more, you know, as leading players, but also nation-states, even. I think this is an international thing. AI's gonna affect every country-- everybody in the world. So I think it's really important that the world and the international community has a say in this. Scott Pelley: Can you teach an AI agent morality? Demis Hassabis: I think you can. They learn by demonstration. They learn by teaching. And I think that's one of the things we have to do with these systems, is to give them a value system and-- a guidance, and some guardrails around that, much in the way that you would teach a child. Google DeepMind is in a race with dozens of others striving for artificial general intelligence so human that you can't tell the difference. Which made us think about Demis Hassabis signing the Nobel Book of Laureates -- when does a machine sign for the first time? And after that, will humans ever sign it again? Demis Hassabis: I think in the next steps is going to be these amazing tools that enhance our, almost every endeavor we do as humans and then beyond that, when AGI arrives, you know, I think, it's gonna change pretty much everything about the way we do things. And its almost you know, I think we need new great philosophers to come about hopefully in the next five, ten, years to understand the implications of this.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google DeepMind, discusses the rapid advancement of AI, its potential to transform society, and the challenges it presents.

The Rise of AI and Its Visionary Leader

Demis Hassabis, the 49-year-old CEO of Google DeepMind, has emerged as a central figure in the rapidly evolving field of artificial intelligence (AI). Recently awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for DeepMind's groundbreaking AlphaFold database, Hassabis envisions AI as a transformative force that could be "10 times bigger than the Industrial Revolution - and maybe 10 times faster"

1

.

Source: CBS

A Prodigy's Journey to AI Leadership

Hassabis's exceptional journey began early in life. A chess prodigy at four, he channeled his winnings into early home computers, laying the foundation for his future in AI

1

. His diverse background, including a stint in the video game industry and academic pursuits in computer science and neuroscience, culminated in the founding of DeepMind in 2010 with a clear mission: "Solve intelligence and then use it to solve everything else"1

.DeepMind's Rapid Progress and Future Vision

Under Hassabis's leadership, DeepMind has made significant strides in AI development. From mastering Atari games to creating the AlphaFold database, the company has consistently pushed the boundaries of what AI can achieve. Hassabis believes that AI is progressing on an "exponential curve," with advancements happening at an increasingly rapid pace

2

.The Promise of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

Hassabis predicts that Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) - AI systems with human-like versatility but superhuman speed and knowledge - could be achieved within the next five to ten years

2

. He envisions AI systems that "really understand everything around you in very nuanced and deep ways" and are embedded in everyday life by 20302

.AI's Potential Impact on Society

The potential applications of AI are vast and transformative. Hassabis suggests that AI could usher in an era of "incredible productivity" and "radical abundance"

1

. In healthcare, AI breakthroughs like AlphaFold could lead to numerous medical advances, potentially even curing diseases1

2

.Related Stories

Challenges and Concerns

Despite his optimism, Hassabis acknowledges the challenges and concerns surrounding AI development. He expresses a wish that tech giants had moved more slowly, allowing for more controlled development and testing

1

. The rapid progress of AI raises questions about who will benefit from these advancements and how to ensure responsible development1

.The Duality of AI Systems

Hassabis highlights the "duality" of AI systems - their ability to do incredible things beyond human design or understanding, coupled with the challenge of ensuring that their knowledge databases are comprehensible to humans

2

. This duality underscores the importance of responsible AI development and governance.The Future of AI Integration

Projects like Astra, an AI companion that can see, hear, and chat about anything, demonstrate the potential for AI to become deeply integrated into daily life

2

. Such advancements raise both excitement about AI's capabilities and concerns about privacy and the nature of human-AI interactions.As AI continues its rapid advancement, Demis Hassabis and DeepMind stand at the forefront of this technological revolution, working to harness its potential while navigating the complex challenges it presents to society.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

SpaceX acquires xAI as Elon Musk bets big on 1 million satellite constellation for orbital AI

Technology

2

French Police Raid X Office as Grok Investigation Expands to Include Holocaust Denial Claims

Policy and Regulation

3

UNICEF Demands Global Crackdown on AI-Generated Child Abuse as 1.2 Million Kids Victimized

Policy and Regulation