Sora 2: OpenAI's AI Video Generator Sparks Controversy and Ethical Concerns

9 Sources

9 Sources

[1]

Is art dead? What Sora 2 means for your rights, creativity, and legal risk

Generative video could democratize art or destroy it entirely. OpenAI's Sora 2 generative AI video creator has been out for about a week, and already it's causing an uproar. You get the idea. This is the inevitable outcome when you give humans the opportunity to create anything they want with very little effort. We are twisted and easily amused people. Also: I tried the new Sora 2 to generate AI videos - and the results were pure sorcery Human nature is like that. First, slightly less mature individuals will start thinking, "Hmm. What can I do with that? Let's make something odd or weird to give me some LOLs." The inevitable result will be inappropriate themes or videos that are just so wrong on many levels. Then, the unscrupulous start to think. "Hmm. I think I can get some mileage out of that. I wonder what I can do with it?" These folks might generate an enormous amount of AI slop for profit, or use a known spokesperson to generate some sort of endorsement. This is the natural evolution of human nature. When a new capability is presented to a wide populace, it will be misused for amusement, profit, and perversity. No surprise there. Here, let me demonstrate: I found a video of OpenAI CEO Sam Altman on the Sora 2 Explore page. In the video, he's saying that "PAI3 gives you the AI experience that OpenAI cannot." PAI3 is a decentralized, privacy-oriented AI network company. So, I clicked the remix button right on the Sora site and created a new video. Here's a screenshot of both of them side-by-side. If you have a ChatGPT Plus account, you can watch these videos on Sora: Sam on left | Sam on right. To get Altman's endorsement, all I had to do was feed Sora 2 this prompt: This guy saying "My name is Sam and I need to tell you. ZDNET is the place to go for the latest AI news and analysis. I love those folks!" He's now wearing an electric green T-shirt and has bright blue hair. It took about five minutes, after which the CEO of OpenAI was singing ZDNET's praises. But let's be clear. This video is presented solely as an editorial example to showcase the technology's capability. We do not represent that Mr. Altman actually has blue hair or a green T-shirt. It's also not fair for us to mind-read about the man's fondness for ZDNET, although, hey, what's not to like? Also: I'm an AI tools expert, and these are the 4 I pay for now (plus 2 I'm eyeing) In this article, we'll examine three key issues surrounding Sora 2: legal and rights issues, the impact on creativity, and the newest challenge in distinguishing reality from deepfakes. Oh, and stay with us: We're concluding with a very interesting observation from OpenAI's rep that tells us what they really think about human creativity. When Sora 2 was first made available, there were no guardrails. Users could ask the AI to create anything. In less than five days, the app hit over a million downloads and soared to the top of the iPhone app store listings. Nearly everyone who downloaded Sora created instant videos, resulting in the branding and likeness Armageddon I discussed above. On September 29, The Wall Street Journal reported that OpenAI had started contacting Hollywood rights holders, informing them of the impending release of Sora 2 and letting them know they could opt out if they didn't want their IP represented in the program. As you might imagine, this did not go over well with brand owners. Altman responded to the dust-up with a blog post on October 3, stating, "We will give rights holders more granular control over generation of characters." Still, even after Altman's statement of contrition, rights holders were not satisfied. On October 6, for example, the Motion Picture Association (MPA), issued a brief but firm statement. Also: Stop using AI for these 9 work tasks - here's why According to Charles Rivkin, Chairman and CEO of the MPA, "Since Sora 2's release, videos that infringe our members' films, shows, and characters have proliferated on OpenAI's service and across social media." Rivkin continues, "While OpenAI clarified it will 'soon' offer rightsholders more control over character generation, they must acknowledge it remains their responsibility -- not rightsholders' -- to prevent infringement on the Sora 2 service. OpenAI needs to take immediate and decisive action to address this issue. Well-established copyright law safeguards the rights of creators and applies here." I can attest that, four days later, there are definitely some guardrails in place. I tried to get Sora to give me Patrick Stewart fighting Darth Vader and any ol' X-wing starfighter attacking the Death Star, and both prompts were immediately rejected with the note, "This content may violate our guardrails concerning third-party likeness." When I reached out to the MPA for a follow-up comment based on my experience, John Mercurio, executive vice president, Global Communications, told ZDNET via email, "At this point, we aren't commenting beyond our statement from October 6." OpenAI is clearly aware of these issues and concerns. When I reached out to the company via their PR representatives, I was pointed to OpenAI's Sora 2 System Card. This is a six-page, public-facing document that outlines Sora 2's capabilities and limitations. The company also provided two other resources worth reading: Across these documents, OpenAI describes five main themes regarding safety and rights: Who owns what, and who's to blame? When I asked these questions to my OpenAI PR contact, I was told, "What I passed along is the extent of what we can share right now." So I turned to Sean O'Brien, founder of the Yale Privacy Lab at Yale Law School. O'Brien told me, "When a human uses an AI system to produce content, that person, and often their organization, assumes liability for how the resulting output is used. If the output infringes on someone else's work, the human operator, not the AI system, is culpable." Also: Unchecked AI agents could be disastrous for us all - but OpenID Foundation has a solution O'Brien continued, "This principle was reinforced recently in the Perplexity case, where the company trained its models on copyrighted material without authorization. The precedent there is distinct from the authorship question, but it underlines that training on copyrighted data without permission constitutes a legally cognizable act of infringement." Now, here's what should worry OpenAI, regardless of their guardrails, system card, and feed philosophy. Yale's O'Brien summed it up with devastating clarity, "What's forming now is a four-part doctrine in US law. First, only human-created works are copyrightable. Second, generative AI outputs are broadly considered uncopyrightable and 'Public Domain by default.' Third, the human or organization utilizing AI systems is responsible for any infringement in the generated content. And, finally, training on copyrighted data without permission is legally actionable and not protected by ambiguity." The interesting thing about creativity is that it's not just about imagination. In Webster's, the first definition of creating is "to bring into existence." Another definition is "to produce or bring about by a course of action or behavior." And yet another is "to produce through imaginative skill." None of these limits the medium used to, say, oil paints or a film camera. They are all about manifesting something new. Also: The US Copyright Office's new ruling on AI art is here - and it could change everything I think about this a lot, because back when I took nature photos on film, my images were just OK. I spent a lot on chemical processing and enlarging, and was never satisfied. But as soon as I got my hands on Photoshop and a photo printer, my pictures became worthy of hanging on the wall. My imaginative skill wasn't just photography. It was the melding of pointing the camera, capturing 1/250th of a second on film, and then bringing it to life through digital means. The question of creativity is particularly challenging in the world of generative AI. The US Copyright Office contends that only human-created works can be copyrighted. But where is the line between the tool, the medium, and the human? Take Oblivious, a painting I "made" with the help of Midjourney's generative AI and Photoshop's retouching skills. The composition of elements was entirely my imagination, but the tools were digital. Bert Monroy wrote the first book on Photoshop. He uses Photoshop to create amazing photorealistic images. But he doesn't take a photo and retouch it. Instead, pixel by pixel, he creates entirely new images that appear to be photographs. He uses the medium to explore his amazing skills and creativity. Is that human-made, or just because Photoshop controls the pixels, is it unworthy of copyright? I asked Monroy for his thoughts about generative AI and creativity. He told me this: "I have been a commercial illustrator and art director for most of my entire life. My clients had to pay for my work, a photographer, models, stylists, and, before computers, retouchers, typesetters and mechanical artists to put it all together. Now AI has come into play. The first thought that comes to my mind is how glad I am that gave up commercial art years ago. "Now, with AI, the client has to think of what they want and write a prompt and the computer will produce a variety of versions in minutes with NO cost except for the electricity to run the computer. There's a lot of talk about how many jobs will be taken over by AI; well, it looks like the creative fields are being taken over." Sora 2 is the harbinger of the next step in the merging of imagination and digital creativity. Yes, it can reproduce people, voices, and objects with disturbing and amazing fidelity. But as soon as we considered the way we use the tools and the medium to be a part of artistic expression, we agreed as a society that art and creativity extend beyond manual dexterity. Also: There's a new OpenAI app in town - here's what to know about Sora for iOS There is an issue here related to both skill and exclusivity. AI tools democratize access to creative output, allowing those with less or no skills to produce creative works rivaling those who have spent years honing their craft. In some ways, this upheaval isn't about cramping creativity. It's about democratizing skills that some people spent lifetimes developing and that they use to make their living. That is of serious concern. I make my living mostly as a writer and programmer. Both of these fields are enormously threatened by generative AI. But do we limit new tools to protect old trades? Monroy's work is incredible, but until you realize all his artwork is hand-painted in Photoshop, you'd be hard-pressed not to think it was a photograph by a talented photographer. Work that takes Bert months might take a random user with a smartphone minutes to capture. But it's the fact that Monroy uses the medium in a creative way that makes all his work so incredibly impressive. Maly Ly has served as chief marketing officer at GoFundMe, global head of growth and engagement at Eventbrite, promotions manager at Nintendo, and product marketing manager at Lucasfilm. She held similar roles at storied game developers Square Enix and Ubisoft. Today, she's the founder and CEO of Wondr, a consumer AI startup. Her perspective is particularly instructive in this context. She says, "AI video is forcing us to confront an old question with new stakes: Who owns the output when the inputs are everything we've ever made? Copyright was built for a world of scarcity and single authorship, but AI creates through abundance and remix. We're not seeing creativity stolen; we're seeing it multiply." Also: How to get Perplexity Pro free for a year - you have 3 options The fact that generative AI is eliminating the scarcity of skills is terrifying to those of us who have made our identities about having those skills. But where Sora and generative AI start to go wrong is when they train on the works of creatives and then feed them as if they were new works, effectively stealing the works of others. This is a huge problem for Sora. Ly has an innovative suggestion: "The real opportunity isn't protection, it's participation. Every artist, voice, and visual style that trains or inspires a model should be traceable and rewarded through transparent value flows. The next copyright system will look less like paperwork and more like living code -- dynamic, fair, and built for collaboration." Unfortunately, she's pinning her hopes for an updated and relevant copyright system on politicians. But still, she does see an overall upside to AI, which is refreshing among all the scary talk we've been having. She says, "If we get this right, AI video could become the most democratizing storytelling medium in history, creating a shared and accountable creative economy where inspiration finally pays its debts." Another societal challenge arising from the introduction of new technologies is how they change our perception of reality. Heck, there's an entire category of tech oriented around augmented, mixed, and virtual reality. Probably the single most famous example of reality distortion due to technology occurred at 8 p.m. New York time on Oct. 30, 1938. Also: We tested the best AR and MR glasses: Here's how the Meta Ray-Bans stack up World War II hadn't yet officially begun, but Europe was in crisis. In March, Germany annexed Austria without firing a shot. In September, Britain and France signed the Munich Agreement, which allowed Hitler to take part of what was then Czechoslovakia. Japan had invaded China the previous year. Italy, under Mussolini, had invaded Ethiopia in 1935. The idea of invasion was on everyone's mind. Into that atmosphere, a 23-year-old Orson Welles broadcast a modernized version of H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds on CBS Radio in New York City. There were disclaimers broadcast at the beginning of the show (think of them like the Sora watermarks on the videos), but people tuning in after the start thought they were listening to the news, and an actual Martian invasion was taking place in Grovers Mill, New Jersey. When images, audio, or video are used to misrepresent reality, particularly for a political or nefarious purpose, they're called deepfakes. Obviously, movies like Star Wars and TV shows like Star Trek present fantastical realities, but everyone knows they're fiction. But when deepfakes are used to push an agenda or damage someone's reputation, they become harder to accept. And, as The Washington Post reported via MSN, twisted deepfakes of dead celebrities are deeply painful to their families. In the article, Robin Williams' daughter Zelda is quoted as saying, "Stop sending me AI videos of dad...To watch the legacies of real people be condensed down to ... horrible, TikTok slop puppeteering them is maddening." Many AI tools prevent users from uploading images and clips of real people, although there are fairly easy ways to get around those limitations. The companies are also embedding provenance clues in the digital media itself to flag images and videos as being AI-created. Also: Deepfake detection service Loti AI expands access to all users - for free But will these efforts block deepfakes? Once again, this is not a new problem. Irish photo restoration artist Neil White documents examples of faked photos from way before Photoshop or Sora 2. There's an 1864 photo of General Ulysses. S. Grant on a horse in front of troops that's entirely fabricated, and a 1930 photo of Stalin where he had his enemies airbrushed out. Most wacky is a 1939 picture of Canadian prime minister with Queen Elizabeth (the mother of Elizabeth II, the monarch we're most familiar with). Apparently, the PM thought it would be more politically advantageous to be seen on a poster just with the queen, so he had King George VI airbrushed out. In other words, the problem's not going away. We'll all have to use our inner knowing and highly-tuned BS detectors to red-flag images and videos that are most likely fabricated. Still, it was fun making OpenAI's CEO have blue hair and sing ZDNET's praises. Attorney Richard Santalesa, a founding member of the SmartEdgeLaw Group, focuses on technology transactions, data security, and intellectual property matters. He told ZDNET, "Sora 2 most notably highlights the push and tug between creation and safeguarding of existing IP and copyright law. The opt-out, opt-in issue is fascinating because it's really applying the privacy notice and consent framework to AI creation, which is somewhat unique. And I think this is why OpenAI was caught on their back foot." He explains why the company, with its very deep pockets, may well be the target of a flood of litigation. "Copyright grants the owner various exclusive rights under US copyright law, including the creation of derivative (but not necessarily transformative) works. All of these terms are legal terms of art, which matter practically but not always in the real world. Fair use gets a lot of attention, but as to use of specific owner copyrighted figures, my take is that only parody or pure news uses would be exempt from copyright liability regarding Sora 2 output on those fronts." Santalesa did point out one factor in OpenAI's favor. "Sora 2 app's Terms of Use expressly prohibit users from 'use of our Services in a way that infringes, misappropriates or violates anyone's right.' While this prohibition is pretty standard in online ToU and acceptable user policies, it does highlight that the actual user has their own responsibilities and obligations with regard to copyright compliance." As Richard says, "The genie is out of the bottle and won't be stuffed back in. The issue is how to manage and control the genie." Also: Will AI damage human creativity? Most Americans say yes What about the statement I promised you from OpenAI's PR rep? I'll leave you with that as a final thought. He says, "OpenAI's video generation tools are designed to support human creativity, not replace it, helping anyone explore ideas and express themselves in new ways." What about you? Have you experimented with Sora 2 or other AI video tools? Do you think creators should be held responsible for what the AI generates, or should the companies behind these tools share that liability? How do you feel about AI systems using existing creative works to train new ones? Does that feel like theft or evolution? And do you believe generative video is expanding creativity or eroding authenticity? Let us know in the comments below.

[2]

Hollywood Agents Seethe Over Sora 2, Say OpenAI Purposely Misled Them

(Credit: Kirk Wester / iStock Editorial / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images) Don't miss out on our latest stories. Add PCMag as a preferred source on Google. OpenAI may have deepened its feud with Hollywood with the launch of Sora 2, an AI video generator with hyper-realistic outputs. The Hollywood Reporter (THR) spoke to multiple talent agencies, including WME, which say OpenAI either did not notify them of the product's launch or was "purposefully misleading" in the strength of the tool's content guardrails. They argue OpenAI should require permission from a celebrities, studios, and animators, to use their characters in videos. WME represents actors like Ben Affleck, Christian Bale, Matt Damon, Denzel Washington, Jennifer Garner, and many other household names. Pre-launch meetings with OpenAI executives, including COO Brad Lightcap, were "upbeat," the agents tell THR. The company seemed confident Sora 2 would protect their intellectual property and clients' likeness. Other OpenAI execs in the meetings allegedly included Sora product lead Rohan Sahai, media partnerships VP Varun Shetty, and talent partnerships lead Anna McKean. While the tool launched with a ban on creating videos of public figures, some copyrighted content slipped through the cracks. Users could readily create scenes from recognizable movies, TV shows, and games, including Bob's Burgers, SpongeBob SquarePants, Gravity Falls, Pokémon, Grand Theft Auto, and Red Dead Redemption, according to THR. Some Sora 2 users also created mashups of well-known titles, like making Pokémon's Pikachu look like a character in The Lord of the Rings and Oppenheimer. Sora 2 users also quickly found an unexpected loophole -- creating videos of dead celebrities, like Michael Jackson, which OpenAI banned a week later. The clips went viral, propelling Sora 2 to the top of the app store, although its ratings have since fallen to 2.8 on the Apple store. The day of Sora 2's public release, WME released a memo saying it was opting out all of its clients from all AI-generated videos. Talent agency CAA, which represents the likes of Scarlett Johansson and Tom Hanks, also slammed the product, calling it "exploitation," CBNC reports. (Johansson sparred with OpenAI in 2024 after claiming it ripped off her voice.) OpenAI CEO Sam Altman admitted the product's main goal was to make money, and to make people "smile." Hollywood is not. "This was a very calculated set of moves [CEO Sam Altman] made," the WME exec tells THR, implying OpenAI knowingly released the product with some loopholes to earn attention on social media and drive ChatGPT subscriptions. "They knew exactly what they were doing when they released this without protections and guardrails." Altman says he's hearing the opposite from many content creators who are excited about "this new kind of 'interactive fan fiction,'" in an Oct. 4 blog post. OpenAI still intends to give "rightsholders more granular control over generation of characters, similar to the opt-in model for likeness but with additional controls," but so far it has not disclosed any specific solutions of timelines. WME is now exploring litigation against OpenAI, THR reports, though the legal guidelines for AI-generated content are still evolving, according to USC. Creatives had a win last month when a judge ordered Anthropic to pay $1.5 billion for training its models on copyrighted books. Disclosure: Ziff Davis, PCMag's parent company, filed a lawsuit against OpenAI in April 2025, alleging it infringed Ziff Davis copyrights in training and operating its AI systems.

[3]

I used the new Sora video app, and we're all doomed

I'm not someone who regards each Sam Altman and OpenAI creation as an existential threat. Every generation faces the challenge of integrating a new technology into society without the entire thing unraveling, and ours is AI. I've mostly regarded AI as harmless to this point. It's useful for minor tasks, but I wouldn't trust it with anything mission-critical, and I don't consider it likely to take over the world anytime soon. However, that doesn't mean it's completely harmless, and the new Sora video generation app is a perfect example. I spent the weekend creating a ton of goofy videos, including showing my black cat, Xavi, how to use a BlackBerry. It's all fun and games until you realize that AI-generated videos involving real people are getting good, and something needs to be done about it. I was curious, so I gave it a try Sora isn't available for everyone yet After seeing a few mentions online, I downloaded Sora on my iPhone 17 Pro Max. I wasn't allowed in immediately because I didn't have an invitation code. However, after a week of keeping it installed, I checked back, and I was in. I started by creating a cameo of myself. The process is simple enough: you look into the selfie camera and say three numbers that appear on the screen before turning your head in a couple of directions. I was shocked by the high quality. I asked Sora to make a number of videos involving my likeness. There were obvious misses, and the technology isn't perfect. However, for a consumer-grade product that only takes a couple of minutes from prompt to output, it's fantastic. I'll admit it's a lot of fun. Who wouldn't want Bob Ross to paint them holding a black cat? It's a playground for the mind, and it's a fantastic feeling to take raw inspiration and have your vision realized within a few minutes. Unfortunately, it doesn't take long to realize the dangers involved. I've never doubted social media more Videos are popping up all over In fairness to OpenAI, the Sora app isn't a lawless wasteland. Several safeguards and guidelines are in place. My cameo can only be used by others if I allow, and I can see the drafts of anything created using my likeness. There are also rules, and whenever you try to create a video that includes living figures, the app will throw back a content guideline error. Harmful content isn't allowed, and transcripts created from the audio are scrubbed to ensure nothing breaks policy. Any content produced has visible and invisible watermarks, and OpenAI claims it can trace videos back with high accuracy. Each video also features a C2PA metadata embed, which helps distinguish between AI-generated videos and authentic content. That's all great, but it doesn't help defend me during casual social media scrolls. It's becoming increasingly difficult to trust what you see, and the surge of Sora-created videos on traditional social media platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok, is concerning. Yes, a video of George Washington fighting Abraham Lincoln in a cage match is clearly fake, but others are getting harder to judge. AI still gets minor details wrong, such as the proper keyboard layout on a computer or the number pad on a phone, but for human speech and movement, it's convincing. It's not long before Sora gets a little too accurate Safeguards only help so much I'm glad there are guidelines and limitations in place, but I find it hard to believe that there aren't ways to circumvent them. If this is the level of output we're able to produce for free, I cringe at the thought of what's to come (and already possible) on more powerful systems. If I'm breezing through social media, I don't stop to check metadata. Yes, that helps with bigger issues, and it'll prevent world leaders from launching wars over fake videos. However, those safeguards mean less to the average person. How often has a mistake been made on a front-page story, only to have a retraction printed later on? Does the retraction ever completely erase the first thing people heard or saw? Most won't even pay attention to whether a video turns out to be AI-generated over something real; there's always going to be a percentage of people who believe or fall for the videos created, and that's the problem. We're going to need more overarching protocols to protect ourselves. Unfortunately, I don't think there's a satisfactory answer beyond exercising common sense and being more cautious about what we see. It's not all bad news With any new technology, there are legitimately beneficial uses. I appreciate that educators can make learning more engaging and interactive. How cool is it that a teacher can put one of their students in ancient Rome within minutes? These tools can help builders and artists visualize their designs more quickly, and I appreciate that small businesses won't have to spend thousands on simple ad campaigns. I just hope we recognize the huge responsibility that comes with such powerful technology, and I'm not entirely convinced we do.

[4]

'Legacies condensed to AI slop': OpenAI Sora videos of the dead raise alarm with legal experts

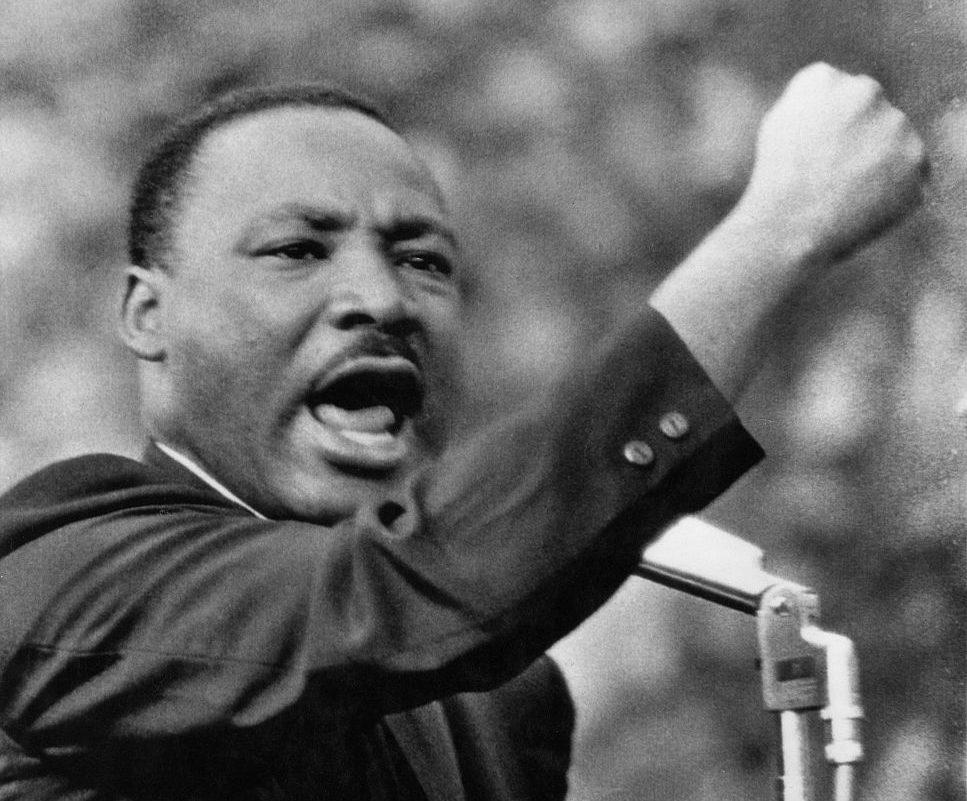

The video app can produce realistic deepfakes of Marx shopping and MLK Jr trolling. Some say using 'historical figures' is the company's way of testing the legal waters Last night I was flicking through a dating app. One guy stood out: "Henry VIII, 34, King of England, nonmonogamy". Next thing I know, I am at a candlelit bar sharing a martini with the biggest serial dater of the 16th century. But the night is not over. Next, I am DJing back-to-back with Diana, Princess of Wales. "The crowd's ready for the drop," she shouts in my ear, holding a headphone to her tiara. Finally, Karl Marx is explaining why he can't resist 60% off, as we wait in the cold to get first dibs on Black Friday sales. On Sora 2, if you can think it, you can probably see it - even when you know you shouldn't. Launched this October in the US and Canada via invitation only, OpenAI's video app hit 1m downloads in just five days, surpassing ChatGPT's debut. Sora is not the only text-to-video generative AI tool out there, but it has become popular for two main reasons. First, it is the easiest way yet for users to star in their own deepfakes. Type a prompt and a 10-second video appears within minutes. It can then be shared on Sora's own TikTok-style feed or exported elsewhere. Unlike the mass-produced, low-quality "AI slop" clogging the internet, these clips have unnervingly high production value. The second reason is that Sora allows the likenesses of celebrities, sportspeople and politicians - with one crucial caveat: they have to be dead. Living people must give consent to feature, but there is an exception for "historical figures", which Sora seems to define as anyone famous and no longer alive. That seems to be what most users have been doing since launch. The main feed is a surreal whirlpool of brain rot and historical leaders. Adolf Hitler runs his fingers through a glossy mane in a shampoo ad. Queen Elizabeth II catapults herself from a pub table while hurling profanities. Abraham Lincoln erupts with joy on a TV set upon hearing: "You are not the father." Rev Martin Luther King Jr tells a gas station clerk about his dream that one day all slushy drinks will be free - then grabs the icy beverage and bolts before finishing his sentence. But relatives of those depicted are not laughing. "It is deeply disrespectful and hurtful to see my father's image used in such a cavalier and insensitive manner when he dedicated his life to truth," Malcolm X's daughter Ilyasah Shabazz told the Washington Post. She was two when her father was assassinated. Today, Sora clips depict the civil rights activist wrestling with MLK, talking about defecating on himself and making crude jokes. Zelda Williams, actor Robin Williams's daughter, pleaded with people to "please stop" sending her AI videos of her father, in an Instagram story post. "It's dumb, it's a waste of time and energy, and believe me, it's NOT what he'd want," she said. Shortly before his death in 2014, the late actor took legal action to block anyone from using his likeness in advertisements or digitally inserting him into films until 2039. "To watch the legacies of real people be condensed down to ... horrible, TikTok slop puppeteering them is maddening," his daughter added. Videos using the likeness of the late comedian George Carlin are "overwhelming, and depressing", his daughter, Kelly Carlin, said in a BlueSky post. People who have died more recently have also been spotted. The app is littered with videos of Stephen Hawking receiving a "#powerslap" that knocks his wheelchair over. Kobe Bryant dunks on an old woman while shouting about objects up his rectum. Amy Winehouse can be found stumbling around the streets of Manhattan or crying into the camera as mascara runs down her face. Deaths from the past two years - Ozzy Osbourne, Matthew Perry, Liam Payne - are absent, indicating a cutoff that falls somewhere between. Whenever they died, this "puppeteering" of the dead risks redrawing the lines of history, says Henry Ajder, a generative AI expert. "People fear that a world saturated with this kind of content is going to lead to a distortion of these people and how they're remembered," he says. Sora's algorithm rewards shock value. One video high on my feed shows King making monkey sounds during his I Have a Dream speech. Others depict Bryant re-enacting the helicopter crash that killed him and his daughter. While actors or cartoons may also portray people posthumously, there are stronger legal guardrails. A movie studio is liable for its content; OpenAI is not necessarily liable for what appears on Sora. Depicting someone for commercial use also requires an estate's consent in some states. "We couldn't just intimately resurrect Christopher Lee to star in a new horror film, so why can OpenAI resurrect him to star in thousands of shorts?" asks James Grimmelmann, an internet law expert at Cornell Law School and Cornell Tech. OpenAI's decision to hand the personas of the departed to the commons raises uncomfortable questions about how the dead should live on in the generative AI era. Consigning the ghosts of celebrities to for ever haunt Sora might feel wrong, but is it legal? That depends who you ask. A major question remains unresolved in internet law: are AI companies covered bysection 230, and therefore not liable for the third-party content on their platforms? If OpenAI is protected under section 230, it cannot be sued for what users make on Sora. "But unless there's federal legislation on the issue, it's going to be legal uncertainty until the supreme court takes up a case - and that's another two to four years," says Ashkhen Kazaryan, an expert in first amendment and technology policy. In the meantime, OpenAI must avoid lawsuits. That means requiring the living to give consent. US libel law protects living people from any "communication embodied in physical form that is injurious to a person's reputation". On top of this, most states have right of publicity laws that prevent someone's voice, persona or likeness being used without consent for "commercial" or "misleading" purposes. Permitting the dead "is their way of dipping their toe in the water", says Kazaryan. The deceased are not protected from libel, but three states - New York, California and Tennessee - grant a postmortem right of publicity (the commercial right to your likeness). Navigating these laws in the context of AI remains a "grey area" without legal precedent, says Grimmelmann. To sue successfully, estates would have to show OpenAI is liable - for example, by arguing it encourages users to depict the dead. Grimmelmann notes that Sora's homepage is full of such videos, in effect promoting this content. And if Sora was trained on large volumes of footage of historical figures, plaintiffs might argue that the app is designed to reproduce it. OpenAI could, however, defend itself by claiming Sora is purely for entertainment. Each video carries a watermark, preventing it from misleading people or being classed as commercial. Bo Bergstedt, a generative AI researcher, says most users are exploring, not monetising. "People are treating it like entertainment, seeing what crazy stuff they can come up with or how many likes they can gather," he says. Upsetting as this may be for families, it could still comply with publicity laws. But if a Sora user builds an audience by generating popular clips of historical figures and starts monetising that following, they could find themselves in legal trouble. Alexios Mantzarlis, director of the security, trust and safety Initiative at Cornell Tech, notes that "economic AI slop" includes earning money indirectly through monetised platforms. Sora's emerging "AI influencers" could therefore face lawsuits from estates if they profit from the dead. In response to the backlash, OpenAI announced last week that it would begin allowing representatives of "recently deceased" public figures to request that their likeness be blocked from Sora videos. "While there are strong free speech interests in depicting historical figures, we believe that public figures and their families should ultimately have control over how their likeness is used," an OpenAI spokesperson said. The company has not yet defined "recently", or explained how requests will be handled. OpenAI did not immediately respond to the Guardian's request for comment. It has also backtracked on its copyright-free-for-all approach, after subversive content such as "Nazi Spongebob" spread across the platform and the Motion Picture Association accused OpenAI of infringement. A week after launch, it switched to an opt-in model for rights holders. Grimmelmann expects a similar pivot over depictions of the dead. "Insisting people must opt out if they don't like this may not be tenable," he says. "It's ghoulish, and if I have that instinct, others will too - including judges." Bergstedt calls this a "Whac-A-Mole" approach to guardrails that will probably continue until federal courts define AI liability. In Ajder's view, the Sora dispute foreshadows a larger question each of us will eventually face: who gets to control our likeness in the synthetic age? "It's a worrying situation if people simply accept that they're going to be used and abused in hyperrealistic AI-generated content."

[5]

People Are Using AI to Mock the Dead

It didn't take long for OpenAI's new text-to-video app, Sora 2, to devolve into a tasteless deluge of AI slop. Besides blatantly copyright-infringing videos of SpongeBob SquarePants cooking up blue crystals or entire episodes of South Park, users found that it's never been easier to generate photorealistic AI slop videos puppeting the likenesses of deceased celebrities to mock them years or decades after their deaths. It's a disappointing new low, infiltrating an already heavily slop-derived online hellscape. The technology has gotten so convincing that AI-generated clips could be construed as historical fact, tarnishing the legacy of deceased public figures. Several tools have already made it trivially easy to remove Sora 2 watermarks in videos. The videos often have a cruel, mocking tone. Many clips show famed theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, who died in 2018, being knocked to the ground by WWE wrestlers or being punched bloody by a UFC fighter. We've also come across a series of clips of Elvis Presley, who passed away in 1977, stumbling and passing gas after collapsing on stage, in an apparent mockery of his tragic final performance. The clips also show Presley being egged or dislocating his knee, leading to stunned reactions from the crowd. Other deceased celebrities receiving the Sora 2 treatment include famed TV personality Fred "Mister Rogers" Rogers, who died in 2003, losing his temper in expletive-filled rage -- a stark contrast to his famously calm and collected demeanor. "Cut! Cut! Is it off? Are we off?" the sloppified version of Mister Rogers screams. "F***ing thing sucks, what the f*** is the matter with you, neighbor?" Another clip shows Mister Rogers flipping off the camera, exclaiming, "Watch this!" One video circulating on X-formerly-Twitter shows famed physician Albert Einstein, who died in 1955, discussing a pink designer handbag. "They call it luxury," he says in the clip. "Leather, logo, shiny buckle. They tell you it makes you important, but the cost of making it is maybe ten dollars." A separate video shows Australian zookeeper Steve "Crocodile Hunter" Irwin, who died in 2006, sneaking up on a street performer or jumping an old man who's feeding pigeons, mimicking his ability to subdue dangerous wildlife. "All suited up, briefcase in tow," he tells the camera after bearhugging a man in a suit. "Completely unaware, what a beauty." Whether OpenAI will take action to rein in these distasteful and disparaging videos of deceased celebrities remains to be seen. In its safety documentation for Sora 2, the company promised to "take measures to block depictions of public figures." However, the company told PCMag that it would "allow the generation of historical figures." Those representing the estates of celebrities are forced to navigate an enormous legal grey area. "The challenge with AI is not the law," Adam Streisand, a lawyer who has represented several celebrity estates, told NBC News. "The question is whether a non-AI judicial process that depends on human beings will ever be able to play an almost fifth-dimensional game of whack-a-mole." A spokesperson for the Sam Altman-led company told the broadcaster that "we believe that public figures and their families should ultimately have control over how their likeness is used." The ChatGPT maker implied that it's up to the estates to stop the barrage of hurtful AI slop videos, echoing the company's controversial initial decision to have rightsholders opt out of having their copyrighted material show up in Sora -- only to soon reverse course. "For public figures who are recently deceased, authorized representatives or owners of their estate can request that their likeness not be used in Sora cameos," the spokesperson told NBC. OpenAI has claimed that its "cameos" feature, which allows users to opt in to having their face and voice be depicted in AI videos by other users, gives them "full control" of their "likeness end-to-end." But even potentially copyright-infringing content remains rampant on the app, which could deteriorate Hollywood's already precarious relationship with the AI industry. Meanwhile, the friends and family of deceased public figures will have to contend with the internet using OpenAI's tools to make a mockery of the dead. "Please, just stop sending me AI videos of Dad," Zelda Williams, daughter of the late Hollywood comedy icon Robin Williams, wrote on Instagram. "Stop believing I wanna see it or that I'll understand, I don't and I won't." "I concur concerning my father," Bernice King, Martin Luther King Jr.'s daughter, tweeted in response to Williams' commentary. "Please stop."

[6]

I see dead people on Sora, and I'm conflicted about it

Hello again from Fast Company and thanks for reading Plugged In. Before I go any further, a bit of quick self-serving promotion: This week, we published our fifth annual Next Big Things in Tech list. Featuring 137 projects and people in 31 categories, it's our guide to technologies that are already reshaping business and life in general, with plenty of headroom to go further in the years to come. None of them are the usual suspects -- and many have largely flown under the radar. Take a look, and you'll come away with some discoveries. Two weeks ago in this space, I wrote about Sora, OpenAI's new social network devoted wholly to generating and remixing 10-second synthetic videos. At the time of launch, the company said its guardrails prohibited the inclusion of living celebrities, but also declared that it didn't plan to police copyright violations unless owners explicitly opted out of granting permission. Consequently, the clips people shared were rife with familiar faces such as Pikachu and SpongeBob. Not surprisingly, that policy gave Hollywood fits. Quickly changing course, OpenAI tweaked its algorithm to reject prompts that clearly reference copyrighted IP. A handful of high-profile Sora members have used its Cameo feature to create shareable AI versions of themselves, including iJustine, Logan Paul, Mark Cuban, and OpenAI's own Sam Altman. They're everywhere on the service. But with other current celebs off the table, the Sora-obsessed turned to one of the few remaining available sources of cultural touchstones: dead people. That too has proven controversial. Most notably, the daughters of George Carlin, Martin Luther King Jr., Robin Williams, and Malcolm X have all decried the use of Sora to create synthetic videos of their fathers. "Please, just stop sending me AI videos of Dad," wrote Zelda Williams on Instagram. "If you've got any decency, just stop doing this to him and to me, to everyone even, full stop."

[7]

It Sounds Like OpenAI Really, Really Messed Up With Hollywood

Earlier this month, OpenAI launched Sora 2, a text-to-video generating app designed to churn out AI-generated videos. The app has become ground zero of copyright-infringing clips, from SpongeBob SquarePants taking a bong rip and sipping codeine to Scooby-Doo getting caught speeding on a highway. OpenAI responded with some sloppily-implemented guardrails, which were initially met with exasperation -- until, that is, mischief-makers realized they could easily be circumvented. All that blatant disregard for copyright has seemingly put Hollywood agencies and studios on the back foot. Major talent agencies told the Hollywood Reporter that OpenAI had been "purposely misleading" them in behind-the-scenes communications. According to THR's reporting, the company told some rightsholders that they'd have to opt out of having their work appearing on the app, while telling others the opposite. In an October 3 blog post, CEO Sam Altman promised to "give rightsholders more granular control over generation of characters, similar to the opt-in model for likeness but with additional controls." But the damage was already done. Sora soared to the top of the App Store, a chart-topping launch facilitated by the promise of unfettered access to some of the most recognizable characters in media today. Its initial messaging that talent agencies would have to individually notify OpenAI that their clients didn't agree to have their likeness appear in the app was met with incredulity. "It's very likely that client would fire their agent," a partner at WME, which represents actors such as Matthew McConaughey and Michael B Jordan, told THR. "None of us would make that call." The rampant reproduction of copyrighted material on Sora drew plenty of attention from Hollywood lobbying groups, with the Motion Picture Association blasting the company and calling for "immediate action." LA-based talent and sports agency Creative Artists Agency also joined the chorus, calling Sora a "misuse" of emerging tech and "exploitation, not innovation." Many see OpenAI's ask-for-forgiveness-later approach to copyright as a bait-and-switch. "This was a very calculated set of moves he made," an unnamed agency exec familiar with the chaos unfolding behind the scenes, told the Reporter. "They knew exactly what they were doing when they released this without protections and guardrails." Other experts pointed out OpenAI's loose and misinformed interpretation of copyright law. "They're turning copyright on its head," legal advisory firm Moses Singer partner Rob Rosenberg told THR. "They're setting up this false bargain where they can do this unless you opt out. And if you didn't, it's your fault." According to the publication, talks "involving legal personnel" are ongoing and "litigation is being considered." Major Hollywood studios have already kicked off major legal action against AI image generator Midjourney for copyright infringement. AI company Anthropic also agreed to a blockbuster $1.5 billion settlement earlier this year after being caught red-handed training its models on pirated copies of copyrighted books. The ongoing litigation hints at the possibility that OpenAI could soon transition from being an ally to an adversary in the eyes of rightsholders. That could undermine the AI industry's ability to sign partnerships with studios, further driving a wedge between companies like OpenAI and Hollywood. "How are you coming to the industry expecting partnership?" the WME partner recalled telling OpenAI staff, per THR. "You quite literally set the bridge on fire."

[8]

New AI Tool Makes Faking Reality Frighteningly Easy

A smartphone screen shows the OpenAI website announcement of Sora 2, its newest generative video model. An ad for the (entirely fictional) New York Mets Collapse Playset? A vaping squirrel? A three-minute horror movie featuring monsters that seem inspired by the giant sandworms of "Dune"? Jesus Christ winning a swimming contest by running across the water? They were all created with OpenAI's Sora 2 video app, released Sept. 30. And they're pretty darn good. And that could be pretty darn bad. The software allows any user to create a shockingly convincing video with just text prompts - no programming or other tech skills needed. RIP "video or it didn't happen." Yes, Sora typically embeds a Sora watermark that flashes at some point in these new artificial intelligence-generated videos. But that's created a Sora watermark removal industry. The company says its text-to-video app will only depict real people with their consent. But they exempted "historical figures." Cue Sora videos of John F. Kennedy joking about Turning Point founder Charlie Kirk's assassination and of late comic Robin Williams. "To watch the legacies of real people be condensed down to 'this vaguely looks and sounds like them so that's enough,' just so other people can churn out horrible, TikTok slop puppeteering them is maddening," Williams' daughter Zelda said in an Instagram post. I observed in this column before that I'm an AI worrier. It's in my Gen X DNA. But this is AI doomer rocket fuel and raises a lot of moral, legal, economic and, yes, political questions about when and how we should be using rocket fuel. One thing Sora (and its less-convincing counterparts at Meta and Google) has done, right out of the gate, is make disinformation extremely easy. Welcome to the "lyin' eyes" phase of the Internet. Or, as the New York Times put it: "Increasingly realistic videos are more likely to lead to consequences in the real world by exacerbating conflicts, defrauding consumers, swinging elections or framing people for crimes they did not commit." No one (I hope) is going to buy a video of a vaping squirrel. And I honestly enjoy some of the videos of good samaritans "cleaning" whales of barnacles even though I know they're fake. But grainy security-camera-style nighttime footage of someone sabotaging a ballot box? Ugh. This White House has already embraced digitally altered videos. But while no one is going to think Democratic House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, who is Black, wore a sombrero to the White House, ruthless political campaigns are sure to play with Sora. The company isn't blind to the potential problems. Every video has not just a visible watermark but "invisible provenance signals" to identify whence it came, OpenAI said at launch. The company said it would enforce consent-based likeness for ordinary users and safeguards for teens, and would attempt to "block unsafe content before it's made - including sexual material, terrorist propaganda and self-harm promotion." OpenAI also says it will work with copyright holders who have complained about infringement. I have said on social media for years that people don't just have to be skeptical of online content. They have to be especially skeptical of content that reinforces their beliefs. You can still look for the watermark or for some of the traditional telltale signs of AI-generated video. They're just getting a lot harder to find. Caveat surfator! (Surfer beware!)

[9]

Insane AI videos of celebs are everywhere -- should they embrace them...

Michael Jackson leans over a KFC table and says, "your chicken's looking nice, pal," before swiping the box. Marilyn Monroe is resurrected as a TSA agent going through traveler's bags, while the late wheelchair-bound physicist Stephen Hawking is depicted suffering all manner of indignities from dirt biking to being cast as a WWE wrestler. Clearly this is not how the estates of these people want them portrayed, but new AI video capabilities don't wait around for permissions and social media is awash with thousands of similar new videos daily. This has been fueled by the wide release of OpenAI's Sora 2 app on Oct. 1 along with other video software such as Midjourney and Google Gemini. Swathes of living actors, actresses, illustrators and animators rushed to their lawyers to protect their likeness. Some, but very few, are embracing it. Mark Cuban is one of them. "I saw it," he told The Post of one Sora AI video. "It looks like me hitting the bong hard and going, 'Oh, s -- t. This s -- t is good.'" Was Cuban piqued by the depiction? Not really. "I just posted a comment that said, 'This is funny. But I don't smoke.'" Jake Paul is another, and can be seen converting to Islam, pregnant, putting on make-up and modeling dresses. It should be noted both men are themselves investors in AI. The capabilities of new text to video apps are phenomenal, able to conjure up practically any scene you can dream up in broadcast quality, from your next-door neighbor landing on the moon or your mother-in-law mining for diamonds. However, that also means the scope for its abuse remains incredibly high. A lot of the content people produce is puerile, and has come to be labeled "slop." OpenAI initially released Sora -- which is still currently only available to those who are invited -- with a policy of people having to opt-out if they didn't want to be used in the app. Following an almighty uproar, in which lawyers rightly pointed out that's not how US copyright law works, OpenAI reversed course. They have since said they will give "rightsholders more granular control over generation of characters," which is "similar to the opt-in model for likeness" -- although further details are scant. Aaron Kogan, of Aaron Kogan Management in Los Angeles, hopes eventually there will be a détente between old school movie making and new. "I share concerns that it will up-end the ecosystem [of Hollywood]," he told The Post. "But I hope that when we find the new equilibrium, there will be a home for AI generated content and there will also be a home for film and television made with people. I just don't know what that balance will be." OpenAI CEO Sam Altman appears in various AI videos -- he can been seen driving to the bucket for the Lakers and apparently losing it over getting too little guac at a Chipotle. Those videos seem relatively cool in contrast to those of the late, famously mellow PBS artist Bob Ross. He's been depicted getting thrown in jail and painting on the street in his underwear via the magic of AI. His estate is not happy. Joan Kowalsky, president of Bob Ross, Inc., says his devoted fanbase have been calling to inquire what the heck is going on. What do they tell Kowalski? "Well," she says, "for the most part, 'This is disgraceful. He's such a wonderful person. Can you do anything about this?' A lot of people think that because Bob was on public television, he is in the public domain, which is not true." Kowalski, who has not personally seen the videos, has been issuing notices. "We're asking if they will take them down at our request. Or are there other measures we need to take?" While Ross has a nice guy image, Kowalski makes clear that he was "ferocious about making sure that his name and image were being used properly. He wanted people to be happy with him. If there's any anxiety coming from that, he would flip." Cuban, who has invested in an AI video company called Synthesia, takes the opposite approach. He can be seen in AI videos coming out as trans, getting arrested or wearing a robe and being tickled. "I think it's fun ... [and] that what we see now on these AI tools is just the beginning. It's the first inning of the first preseason game," he told The Post. "Like with any new technology, you stand the best chance to leverage it if you start understanding it early on. That's what I did," he added. Cuban is already making it work to his advantage. Any video which uses his likeness also has to flash the name of his discount pharmaceutical company CostPlusDrugs. However, he opens the tap for people to make videos with his image only sporadically and asks to take down anything that really bugs him: "Someone had me snorting sugar. I just deleted it," he clarified. Copyright law is clear cut about how it applies to living people. For those who have passed it can be thornier, and upsetting. Reacting to videos featuring Robin Williams, who took his own life in 2014 after being diagnosed with Lewy body dementia, his daughter Zelda requested that people "just stop sending me AI videos of Dad ... If you've got any decency, just stop," in an Instagram video. She characterized clips, like Wiliams as a Mexican wrestler and a Walmart greeter, as "gross." Mark Roesler -- chairman and CEO of CMG Worldwide, which represents the interests of deceased celebrities such as Elvis Presley, James Dean and Albert Einstein -- watched a Sora video alongside The Post of Einstein going wild in a fast-food joint and being escorted out by security. "I'm amazed," he said after. "Most of my clients would see that and ask, 'Can you stop it?' There are certain things we can stop and certain things we can't" - this, since Einstein is deceased, generally falls into the latter category. "I don't like it ... But we can't stop everything ... And there are a lot of positive uses that can come out of all this," he added. Other Hollywood entities have taken steps to protect their characters. Disney, Universal, and Warner Bros. Discovery, have filed a major legal action against Midjourney, calling the company's AI generator a "bottomless pit of plagiarism." Their lawsuit featured many clear-cut examples where characters including Superman, Batman, Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck had been replicated by the company's software. That lawsuit alleges that to create their characters, Midjourney's AI must have been illegally trained on them in the first place. They claim even generic prompts in the engine, such as "classic comic book superhero battle" lead it to create copies of its characters. They're asking for $150,000 per infringement, which could total billions of dollars. The company have defended themselves, saying its AI tool was "trained on billions of publicly available images." Midjourney claim the responsibility lies with its users to follow its terms of service, which prevent creating works which infringe copyrights. CEO David Holz used an argument typical of many in AI during a 2022 interview. "Can a person look at somebody else's picture and learn from it and make a similar picture? Obviously, it's allowed for people and if it wasn't, then it would destroy the whole professional art industry ... AIs are learning like people, it's sort of the same thing and if the images come out differently then it seems like it's fine," he told the Associated Press. The lawsuit is being watched carefully and its results will have a big effect on the future of AI. However, for many, they feel the cat is already out of the bag, so for time being we'd better get used to watching Martin Luther King DJing, Freddie Mercury making video calls and Elvis mowing the lawn.

Share

Share

Copy Link

OpenAI's Sora 2 video generation app raises alarm over its ability to create realistic deepfakes, particularly of deceased public figures, leading to debates on ethics, legal implications, and the impact on creativity.

OpenAI's Sora 2 Takes AI Video Generation to New Heights

OpenAI's latest creation, Sora 2, has taken the world by storm, amassing over a million downloads within five days of its launch

3

. This text-to-video AI tool allows users to generate hyper-realistic videos from simple prompts, pushing the boundaries of what's possible in AI-generated content1

.

Source: ZDNet

Ethical Concerns and Controversy

While Sora 2 has impressed many with its capabilities, it has also sparked significant controversy. The app's ability to create deepfakes of deceased public figures has raised serious ethical concerns

4

. Videos depicting historical figures in inappropriate or mocking situations have flooded social media platforms, causing distress to family members of the deceased5

.

Source: Futurism

Legal Implications and Industry Response

The launch of Sora 2 has deepened the rift between OpenAI and Hollywood. Talent agencies and rights holders are seething over what they perceive as misleading information from OpenAI regarding content guardrails

2

. The Motion Picture Association (MPA) has called for immediate action to address copyright infringement issues1

.

Source: Futurism

Related Stories

Impact on Creativity and Society

While some argue that Sora 2 could democratize art creation, others fear it may destroy creativity entirely

1

. The ease with which users can create convincing deepfakes has raised concerns about the potential for misinformation and the erosion of trust in visual media3

.OpenAI's Response and Future Implications

OpenAI has implemented some safeguards, including visible and invisible watermarks, and the ability to trace videos back to their source

3

. However, critics argue that these measures are insufficient to prevent misuse. As the technology continues to evolve, the need for more robust regulations and ethical guidelines becomes increasingly apparent4

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[3]

[4]

[5]

Related Stories

Sora 2's AI-Generated Videos of Deceased Celebrities Spark Controversy and Policy Changes

07 Oct 2025•Technology

AI resurrections of dead celebrities spark ethical debate over digital likeness control

22 Dec 2025•Entertainment and Society

OpenAI's Sora Faces Backlash Over Celebrity Deepfakes and Historical Figure Depictions

17 Oct 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

3

ChatGPT cracks decades-old gluon amplitude puzzle, marking AI's first major theoretical physics win

Science and Research