Stanford's SleepFM AI predicts 130+ diseases from a single night's sleep data

4 Sources

4 Sources

[1]

Stanford's AI spots hidden disease warnings that show up while you sleep

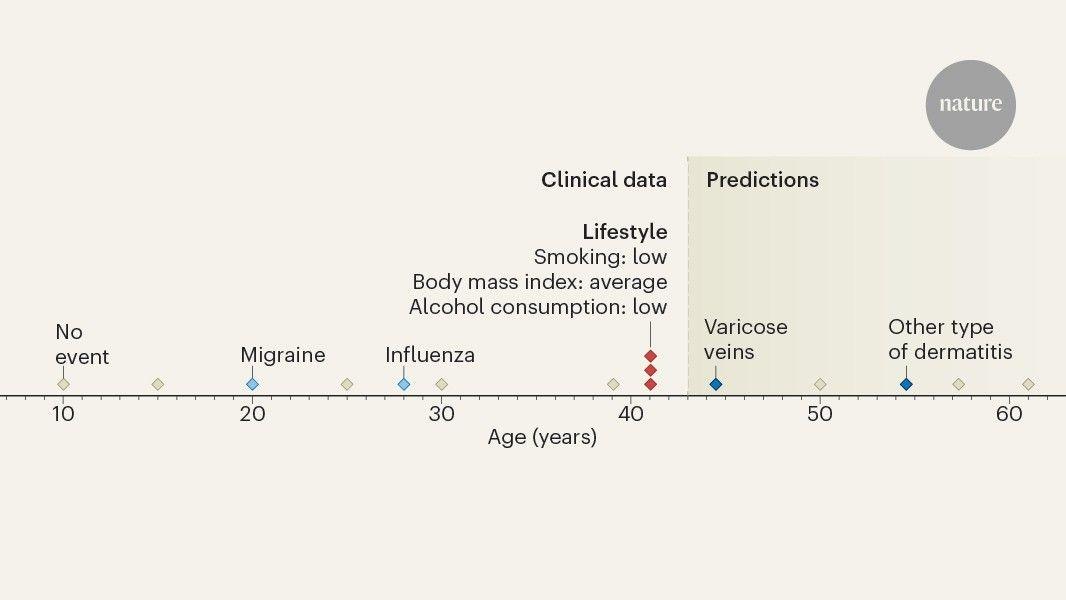

A restless night often leads to fatigue the next day, but it may also signal health problems that emerge much later. Scientists at Stanford Medicine and their collaborators have developed an artificial intelligence system that can examine body signals from a single night of sleep and estimate a person's risk of developing more than 100 different medical conditions. The system, called SleepFM, was trained using almost 600,000 hours of sleep recordings from 65,000 individuals. These recordings came from polysomnography, an in-depth sleep test that uses multiple sensors to track brain activity, heart function, breathing patterns, eye movement, leg motion, and other physical signals during sleep. Sleep Studies Hold Untapped Health Data Polysomnography is considered the gold standard for evaluating sleep and is typically performed overnight in a laboratory setting. While it is widely used to diagnose sleep disorders, researchers realized it also captures a vast amount of physiological information that has rarely been fully analyzed. "We record an amazing number of signals when we study sleep," said Emmanual Mignot, MD, PhD, the Craig Reynolds Professor in Sleep Medicine and co-senior author of the new study, which will publish Jan. 6 in Nature Medicine. "It's a kind of general physiology that we study for eight hours in a subject who's completely captive. It's very data rich." In routine clinical practice, only a small portion of this information is examined. Recent advances in artificial intelligence now allow researchers to analyze these large and complex datasets more thoroughly. According to the team, this work is the first to apply AI to sleep data on such a massive scale. "From an AI perspective, sleep is relatively understudied. There's a lot of other AI work that's looking at pathology or cardiology, but relatively little looking at sleep, despite sleep being such an important part of life," said James Zou, PhD, associate professor of biomedical data science and co-senior author of the study. Teaching AI the Patterns of Sleep To unlock insights from the data, the researchers built a foundation model, a type of AI designed to learn broad patterns from very large datasets and then apply that knowledge to many tasks. Large language models like ChatGPT use a similar approach, though they are trained on text rather than biological signals. SleepFM was trained on 585,000 hours of polysomnography data collected from patients evaluated at sleep clinics. Each sleep recording was divided into five-second segments, which function much like words used to train language-based AI systems. "SleepFM is essentially learning the language of sleep," Zou said. The model integrates multiple streams of information, including brain signals, heart rhythms, muscle activity, pulse measurements, and airflow during breathing, and learns how these signals interact. To help the system understand these relationships, the researchers developed a training method called leave-one-out contrastive learning. This approach removes one type of signal at a time and asks the model to reconstruct it using the remaining data. "One of the technical advances that we made in this work is to figure out how to harmonize all these different data modalities so they can come together to learn the same language," Zou said. Predicting Future Disease From Sleep After training, the researchers adapted the model for specific tasks. They first tested it on standard sleep assessments, such as identifying sleep stages and evaluating sleep apnea severity. In these tests, SleepFM matched or exceeded the performance of leading models currently in use. The team then pursued a more ambitious objective: determining whether sleep data could predict future disease. To do this, they linked polysomnography records with long-term health outcomes from the same individuals. This was possible because the researchers had access to decades of medical records from a single sleep clinic. The Stanford Sleep Medicine Center was founded in 1970 by the late William Dement, MD, PhD, who is widely regarded as the father of sleep medicine. The largest group used to train SleepFM included about 35,000 patients between the ages of 2 and 96. Their sleep studies were recorded at the clinic between 1999 and 2024 and paired with electronic health records that followed some patients for as long as 25 years. (The clinic's polysomnography recordings go back even further, but only on paper, said Mignot, who directed the sleep center from 2010 to 2019.) Using this combined dataset, SleepFM reviewed more than 1,000 disease categories and identified 130 conditions that could be predicted with reasonable accuracy using sleep data alone. The strongest results were seen for cancers, pregnancy complications, circulatory diseases, and mental health disorders, with prediction scores above a C-index of 0.8. How Prediction Accuracy Is Measured The C-index, or concordance index, measures how well a model can rank people by risk. It reflects how often the model correctly predicts which of two individuals will experience a health event first. "For all possible pairs of individuals, the model gives a ranking of who's more likely to experience an event -- a heart attack, for instance -- earlier. A C-index of 0.8 means that 80% of the time, the model's prediction is concordant with what actually happened," Zou said. SleepFM performed especially well when predicting Parkinson's disease (C-index 0.89), dementia (0.85), hypertensive heart disease (0.84), heart attack (0.81), prostate cancer (0.89), breast cancer (0.87), and death (0.84). "We were pleasantly surprised that for a pretty diverse set of conditions, the model is able to make informative predictions," Zou said. Zou also noted that models with lower accuracy, often around a C-index of 0.7, are already used in medical practice, such as tools that help predict how patients might respond to certain cancer treatments. Understanding What the AI Sees The researchers are now working to improve SleepFM's predictions and better understand how the system reaches its conclusions. Future versions may incorporate data from wearable devices to expand the range of physiological signals. "It doesn't explain that to us in English," Zou said. "But we have developed different interpretation techniques to figure out what the model is looking at when it's making a specific disease prediction." The team found that while heart-related signals were more influential in predicting cardiovascular disease and brain-related signals played a larger role in mental health predictions, the most accurate results came from combining all types of data. "The most information we got for predicting disease was by contrasting the different channels," Mignot said. Body constituents that were out of sync -- a brain that looks asleep but a heart that looks awake, for example -- seemed to spell trouble. Rahul Thapa, a PhD student in biomedical data science, and Magnus Ruud Kjaer, a PhD student at Technical University of Denmark, are co-lead authors of the study. Researchers from the Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen University Hospital -Rigshospitalet, BioSerenity, University of Copenhagen and Harvard Medical School contributed to the work. The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant R01HL161253), Knight-Hennessy Scholars and Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub.

[2]

AI trained on sleep data predicts future disease and mortality years in advance

By Tarun Sai LomteReviewed by Lauren HardakerJan 8 2026 By learning hidden physiological patterns from overnight sleep studies, a new AI foundation model reveals how sleep can serve as an early warning system for disease risk years before clinical diagnosis. Study: A multimodal sleep foundation model for disease prediction. Image credit: AnnaStills/Shutterstock.com In a recent study published in Nature Medicine, researchers developed a multimodal sleep foundation model, SleepFM, for disease prediction. From sleep disorders to systemic disease risk Sleep disorders impact millions of individuals and are increasingly recognized as contributors to and indicators of various conditions. Polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard for sleep analysis, capturing rich physiological signals. Previous machine learning studies have typically targeted individual diseases or limited sleep metrics, leaving much of the rich complexity captured by PSG underused. SleepFM links overnight physiology to long-term disease risk In the present study, researchers developed SleepFM, a multimodal sleep foundation model, for disease prediction. PSG data were used from four cohorts: BioSerenity, the Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men (MrOS), the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and Stanford Sleep Clinic (SSC). Together, these cohorts comprised around 65,000 participants and 585,000 hours of sleep recordings. In addition, the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) dataset was used to evaluate external transfer learning and generalization and was excluded from pretraining. The team employed a self-supervised contrastive learning objective for pretraining. After pretraining, the performance of SleepFM's learned representations was assessed by fine-tuning on four benchmark tasks: sex classification, sleep stage classification, age estimation, and sleep apnea classification. SleepFM's ability to predict chronological age was assessed for age estimation. The model achieved a mean absolute error of 7.33 years. Performance varied by age group, with higher accuracy in middle-aged and pediatric groups and greater error in older adults. Sex classification had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.86 and an area under the precision, recall curve of 0.9. SleepFM performed well in distinguishing wake, stage 2, and rapid eye movement stages but showed confusion in transitional sleep stages, such as stage 1, in line with known variability in scoring. Notably, the model achieved competitive performance compared to state-of-the-art models, including U-Sleep, Greifswald Sleep Stage Classifier (GSSC), Yet Another Spindle Algorithm (YASA), and STAGES, although specialized models occasionally outperformed SleepFM on certain external datasets. For sleep apnea classification, SleepFM demonstrated competitive performance, with accuracies of 0.87 and 0.69 for presence and severity classification, respectively. Next, the researchers linked SSC data with electronic health records, extracting diagnostic codes and their timestamps for disease prediction. These codes were mapped to a hierarchical system of more than 1,800 disease categories designed for phenome-wide association studies (phecodes). After filtering for prevalence and temporal constraints, 1,041 phecodes were retained for evaluation, with cases defined as diagnoses occurring more than seven days after the sleep study to avoid trivial associations. SleepFM achieved robust results in various areas, including pregnancy-related complications, mental disorders, neoplasms, and circulatory conditions. The model achieved an AUROC of 0.93 for Parkinson's disease and 0.84 for both developmental delays and disorders and mild cognitive impairment, measured over a six-year prediction window. Among circulatory conditions, SleepFM effectively predicted intracranial hemorrhage and hypertensive heart disease with six-year AUROC values of 0.82 and 0.88, respectively. The authors emphasize that these predictions reflect statistical risk stratification rather than causal relationships or imminent disease onset. Among neoplasms, SleepFM demonstrated strong predictive performance for prostate cancer, melanomas of the skin, and breast cancer. The team then examined the model's generalization capabilities across temporal distribution and external site validation. For temporal generalization, the model was tested on a separate cohort of Stanford patients from 2020 onwards; SleepFM maintained strong predictive performance despite the limited follow-up period. To evaluate cross-site generalization, the transfer learning capabilities of SleepFM were assessed on the SHHS dataset. Embeddings from the pretrained model were extracted and fine-tuned on a subset of this dataset. Because outcome definitions differed across sites, evaluation was limited to six overlapping cardiovascular outcomes. SleepFM demonstrated robust transfer learning performance across these key outcomes, achieving significant predictive accuracy for congestive heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. Finally, the researchers compared SleepFM against two supervised baselines, end-to-end PSG and demographics. The demographics baseline was trained on structured clinical features, for example, body mass index, age, sex, and race or ethnicity. The end-to-end PSG model was trained on raw PSG data, including age and sex, but without pre-training. The percentage difference in AUROC between the two baselines and SleepFM ranged from 5 % to17 %. SleepFM consistently outperformed both baselines across most categories of diseases. Moreover, SleepFM was superior in predicting all-cause mortality, achieving an AUROC of 0.85, compared to both baselines that had an AUROC of 0.78. Across disease categories, the model demonstrated strong risk stratification performance, with more than 130 conditions achieving a Harrell's C index of at least 0.75. According to the authors, these results highlight the potential of sleep as a rich, underused source of longitudinal health signals. Sleep-based AI models could reshape early disease detection In summary, the study developed a large-scale sleep foundation model using more than 585,000 hours of PSG data. SleepFM was robust in predicting dementia, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and death. The model achieved competitive performance on standard tasks, such as apnea detection and sleep staging, comparable to state-of-the-art models. SleepFM also showed strong transfer learning capabilities, maintaining robust predictive power for several cardiovascular outcomes across independent datasets. Furthermore, the model outperformed supervised baselines across diverse disease categories, predicting all-cause mortality more accurately than both baselines. However, the authors note that most data were derived from individuals referred for clinical sleep studies, which may limit generalizability to the broader population. They also acknowledge that, like many foundation models, SleepFM's learned representations are not yet fully interpretable at the level of specific physiological mechanisms. Overall, these findings suggest that SleepFM could complement existing risk assessment tools and help identify early disease signs. Future studies may explore how integrating sleep models with data from health records, imaging, and omics can enhance their utility. Download your PDF copy now! Journal reference: Thapa R, Kjaer MR, He B, et al. (2026). A multimodal sleep foundation model for disease prediction. Nature Medicine. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-025-04133-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04133-4. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-025-04133-4

[3]

Sleep data can help predict disease risk years in advance

One bad night can leave you foggy the next morning. But new research suggests a single night's sleep may also carry clues about illnesses that won't appear for years. In one test, an AI system used overnight physiological signals to estimate a person's risk for more than 100 future health conditions. The model, called SleepFM, was developed by Stanford Medicine researchers and collaborators. It was trained on nearly 600,000 hours of polysomnography data from about 65,000 people, using the kind of overnight sleep study that tracks the brain, heart, breathing, movement, and more. Polysomnography is often treated as a clinical tool: you do the study, score sleep stages, look for sleep apnea, and move on. The team argues that's only a small slice of what these recordings contain. "We record an amazing number of signals when we study sleep," said co-senior author Emmanuel Mignot, a professor of sleep medicine at Stanford. "It's a kind of general physiology that we study for eight hours in a subject who's completely captive. It's very data rich." The problem, until recently, was that humans and standard software could only digest so much of that complexity. AI changes that equation, at least in principle, by learning patterns across thousands of nights and multiple body systems at once. Medical AI has been booming in fields like radiology and cardiology. Sleep has lagged behind, even though it sits at the intersection of brain function, metabolism, breathing, and cardiovascular health. Study co-senior author James Zou is an associate professor of biomedical data science. "From an AI perspective, sleep is relatively understudied. There's a lot of other AI work that's looking at pathology or cardiology, but relatively little looking at sleep, despite sleep being such an important part of life," said Zou. That gap shaped the team's approach. Instead of building a model for a single task, they developed a foundation model designed to learn broad patterns first and adapt to specific predictions later. SleepFM was trained like a large language model, but instead of words, it learned from tiny slices of physiology. The polysomnography recordings were chopped into five second segments, so the model could process long nights as sequences and learn what normally follows what. "SleepFM is essentially learning the language of sleep," Zou said. The model pulled in multiple channels at once, including signals such as electroencephalography for brain activity, electrocardiography for heart rhythms, electromyography for muscle activity, plus pulse and airflow data. The goal wasn't just to read each channel. It was to understand how the channels relate to one another. To do that, the researchers created a training method designed to make the model fill in blanks. One stream of data would be hidden, and the model would have to reconstruct it from the others. "One of the technical advances that we made in this work is to figure out how to harmonize all these different data modalities so they can come together to learn the same language," Zou said. After training, the team fine-tuned SleepFM for familiar sleep medicine tasks. They tested whether it could classify sleep stages and assess sleep apnea severity, among other standard measures. On those benchmarks, the system performed as well as or better than leading models already used in the field. That step mattered because it suggested the model wasn't just learning noise. It could do the basics reliably before being asked to do something more ambitious. Then came the real swing: forecasting future disease from one night's sleep. To do this, the researchers paired sleep data with long-term medical outcomes, using decades of patient records from a major sleep clinic. The Stanford Sleep Medicine Center was founded in 1970 by the late William Dement. For this project, the largest dataset came from about 35,000 patients aged 2 to 96 whose polysomnography tests were recorded between 1999 and 2024. The team matched those sleep studies to electronic health records, giving up to 25 years of follow-up data for some individuals. SleepFM scanned more than 1,000 disease categories and identified 130 that it could predict with reasonable accuracy using sleep data alone. The strongest results were reported for cancers, pregnancy complications, circulatory conditions, and mental disorders, with a C-index above 0.8 in those groups. The C-index is a way to score how well a model ranks risk across people. It's not about certainty for one person. It's about whether the model tends to place higher-risk individuals above lower-risk ones. "For all possible pairs of individuals, the model gives a ranking of who's more likely to experience an event - a heart attack, for instance - earlier. A C-index of 0.8 means that 80% of the time, the model's prediction is concordant with what actually happened," Zou said. The model performed especially well for several specific outcomes, including Parkinson's disease, dementia, hypertensive heart disease, heart attack, prostate cancer, breast cancer, and death. "We were pleasantly surprised that for a pretty diverse set of conditions, the model is able to make informative predictions," Zou said. Even with strong performance numbers, the obvious question remains: what exactly is SleepFM picking up? The team says they're working on interpretation tools and may also try improving predictions by adding data from wearables. "It doesn't explain that to us in English," Zou said. "But we have developed different interpretation techniques to figure out what the model is looking at when it's making a specific disease prediction." One pattern already stands out. The most accurate predictions didn't come from a single channel. They came from comparing channels and spotting mismatches. "The most information we got for predicting disease was by contrasting the different channels," Mignot said. In other words, it may be the body being out of sync that signals trouble. A brain that looks asleep while the heart looks "awake," for example, could hint that something deeper is off. Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

[4]

Sleep Lab Data Can Predict Illnesses Years Earlier, Study Finds

By Dennis Thompson HealthDay ReporterWEDNESDAY, Jan. 7, 2026 (HealthDay News) -- Your body is talking while you sleep, and what it's saying could help doctors predict your future risk for major diseases, a new study says. An experimental artificial intelligence (AI) called SleepFM can use people's sleep data to predict their risk of developing more than 100 health problems, researchers reported Jan. 6 in the journal Nature Medicine. SleepFM excelled at predicting conditions as varied as cancers, pregnancy complications, heart problems and mental disorders, the study reported. It also could predict a person's overall risk of death, researchers noted. "SleepFM is essentially learning the language of sleep," co-senior researcher James Zou said in a news release. He's an associate professor of biomedical data science at Stanford Medicine. Researchers trained the AI on 585,000 hours of sleep data from 65,000 people who'd had their sleep monitored at a sleep center. These comprehensive sleep assessments record brain activity, heart activity, breathing, leg movements, eye movements and more, researchers said. "We record an amazing number of signals when we study sleep," co-senior researcher Dr. Emmanuel Mignot, a professor of sleep medicine at Stanford, said in a news release. "It's a kind of general physiology that we study for eight hours in a subject who's completely captive. It's very data rich." The team then used long-term data from the Stanford Sleep Medicine Center to tie sleep data to health risks. About 35,000 patients went to the center for sleep assessment and were followed for up to 25 years. SleepFM analyzed more than 1,000 disease categories in the patients' health records, and found 130 that could be predicted with reasonable accuracy by their sleep data, researchers said. They used a statistic called the C-index, or concordance index, to test the AI's ability to predict diseases. A C-index of 0.8 or higher shows it can predict disease accurately. "A C-index of 0.8 means that 80% of the time, the model's prediction is concordant with what actually happened," Zou said. SleepFM's predictions were particularly strong regarding Parkinson's disease (C-index 0.89), dementia (0.85); hypertensive heart disease (0.84); heart attack (0.81); prostate cancer (0.89); breast cancer (0.87); and death (0.84). "We were pleasantly surprised that for a pretty diverse set of conditions, the model is able to make informative predictions," Zou said. The team found that there was some cross-talk when it came to the heart and head while sleeping. Heart signals during sleep factored more prominently in heart disease predictions, while brain signals did so with mental health predictions, researchers said. However, combining all the data coming in produced the most accurate predictions. "The most information we got for predicting disease was by contrasting the different channels," Mignot said. Sleep data that appeared out of sync -- a brain that looks asleep but a heart that looks awake, for example -- seemed to spell trouble for a person's health. The team is now working on ways to further improve SleepFM's predictions, possibly by adding data from other devices such as wearables. Researchers also are trying to better understand what SleepFM is looking at when it makes its predictions. "It doesn't explain that to us in English," Zou said. "But we have developed different interpretation techniques to figure out what the model is looking at when it's making a specific disease prediction." More information The Sleep Foundation has more on sleep lab studies for patients. SOURCE: Stanford Medicine, news release, Jan. 6, 2026

Share

Share

Copy Link

Researchers at Stanford Medicine developed SleepFM, an AI foundation model that analyzes overnight sleep study data to predict risk for more than 130 medical conditions years before diagnosis. Trained on 585,000 hours of polysomnography recordings from 65,000 individuals, the system excels at forecasting cancers, pregnancy complications, circulatory diseases, and mental health disorders by detecting hidden physiological patterns during sleep.

SleepFM Transforms Sleep Data Into Predictive Health Insights

A restless night might reveal more than just tomorrow's fatigue. Scientists at Stanford Medicine have developed SleepFM, an AI foundation model that examines sleep data to predict risk of medical conditions years before symptoms appear

1

. Published in Nature Medicine, this research demonstrates how AI trained on sleep data can identify hidden physiological patterns that signal future disease2

.The system was trained on nearly 585,000 hours of polysomnography recordings from approximately 65,000 individuals

3

. Polysomnography captures brain activity, heart function, breathing patterns, eye movement, leg motion, and other physiological signals during overnight sleep study sessions. While these comprehensive assessments are typically used only to diagnose sleep disorders, researchers recognized they contain vast amounts of underutilized health information.

Source: Earth.com

"We record an amazing number of signals when we study sleep," said Emmanuel Mignot, the Craig Reynolds Professor in Sleep Medicine and co-senior author. "It's a kind of general physiology that we study for eight hours in a subject who's completely captive. It's very data rich"

1

.AI Foundation Model Learns the Language of Sleep

SleepFM operates as a foundation model, similar to large language models like ChatGPT but trained on biological signals rather than text. The researchers divided each sleep recording into five-second segments that function like words in a language-based system

3

. This approach allows the model to process long nights as sequences and learn normal patterns across multiple data streams.

Source: ScienceDaily

"SleepFM is essentially learning the language of sleep," explained James Zou, associate professor of biomedical data science and co-senior author

4

. The team developed a training method called leave-one-out contrastive learning, which removes one type of signal at a time and asks the model to reconstruct it using remaining data. This technical advance helped harmonize different data modalities so they could work together effectively1

.Disease Prediction Across 130 Medical Conditions

After initial training, researchers linked polysomnography records with long-term health outcomes from the Stanford Sleep Medicine Center, founded in 1970 by the late William Dement. The largest dataset included approximately 35,000 patients aged 2 to 96, with sleep studies recorded between 1999 and 2024 paired with electronic health records tracking some individuals for up to 25 years

1

.SleepFM analyzed more than 1,000 disease categories and identified 130 conditions that could be predicted with reasonable accuracy using sleep data alone

3

. The system demonstrated particularly strong performance for cancers, pregnancy complications, circulatory diseases, and mental health disorders, achieving prediction scores above a C-index of 0.82

.The C-index, or concordance index, measures how well a model ranks risk across individuals. "A C-index of 0.8 means that 80% of the time, the model's prediction is concordant with what actually happened," Zou clarified

3

.Strongest Results for Specific Conditions and Mortality

SleepFM achieved notably high accuracy for several specific outcomes. For Parkinson's disease, the model reached a C-index of 0.93 over a six-year prediction window

2

. Other strong predictions included dementia (0.85), hypertensive heart disease (0.84), heart attack (0.81), prostate cancer (0.89), and breast cancer (0.87)4

.The system also demonstrated the ability to predict overall mortality risk with a C-index of 0.84

4

. Researchers emphasize these predictions reflect statistical risk stratification rather than causal relationships or imminent disease onset2

.Related Stories

Cross-Talk Between Body Systems Reveals Health Clues

The research revealed intriguing patterns in how different physiological signals contribute to disease prediction. Heart signals during sleep factored more prominently in predictions for circulatory diseases, while brain signals played larger roles in mental health disorder forecasts

4

. However, combining all available data streams produced the most accurate predictions for early disease detection."The most information we got for predicting disease was by contrasting the different channels," Mignot noted. Sleep data showing misalignment between body systems—such as a brain that appears asleep while the heart shows waking patterns—seemed particularly indicative of future health problems

4

.What This Means for Future Healthcare

From an AI perspective, sleep has been relatively understudied compared to fields like pathology or cardiology, despite being such a vital part of life

1

. This work represents the first application of AI to sleep data on such a massive scale, opening new possibilities for how overnight sleep study data could serve as an early warning system.The team is now working to improve SleepFM's predictions by potentially incorporating data from wearable devices and developing better interpretation techniques to understand what the model identifies when making specific disease predictions. "It doesn't explain that to us in English," Zou said, "But we have developed different interpretation techniques to figure out what the model is looking at"

4

.For clinicians and patients, this research suggests sleep studies could evolve beyond diagnosing sleep disorders to become comprehensive health screening tools. The ability to predict future health conditions from a single night's physiological data could enable earlier interventions and more personalized preventive care strategies, particularly for conditions like Parkinson's disease, various cancers, and cardiovascular diseases where early detection significantly impacts outcomes.

References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Revolutionary AI Model Analyzes Full Night of Sleep with High Accuracy in Largest Study to Date

18 Mar 2025•Science and Research

AI Model Predicts Disease Onset Up to 20 Years in Advance

02 Oct 2025•Science and Research

AI Model Predicts Future Health Risks for Over 1,000 Diseases

17 Sept 2025•Science and Research

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Pentagon Summons Anthropic CEO as $200M Contract Faces Supply Chain Risk Over AI Restrictions

Policy and Regulation

3

Canada Summons OpenAI Executives After ChatGPT User Became Mass Shooting Suspect

Policy and Regulation