AI in Education: Transforming Classrooms and Challenging Traditional Learning Models

6 Sources

6 Sources

[1]

AI Has Broken High School and College

A conversation between Ian Bogost and Lila Shroff about how school has turned into a free-for-all Another school year is beginning -- which means another year of AI-written essays, AI-completed problem sets, and, for teachers, AI-generated curricula. For the first time, seniors in high school have had their entire high-school careers defined to some extent by chatbots. The same applies for seniors in college: ChatGPT released in November 2022, meaning unlike last year's graduating class, this year's crop has had generative AI at its fingertips the whole time. My colleagues Ian Bogost and Lila Shroff both recently wrote articles about these students and the state of AI in education. (Ian, a university professor himself, wrote about college, while Lila wrote about high school.) Their articles were striking: It is clear that AI has been widely adopted, by students and faculty alike, yet the technology has also turned school into a kind of free-for-all. I asked Lila and Ian to have a brief conversation about their work -- and about where AI in education goes from here. This interview has been edited and condensed. Lila Shroff: We're a few years into AI in schools. Is the conversation maturing or changing in some way at universities? Ian Bogost: Professors are less surprised that it exists, but there is maybe a bit of a blind spot to the state of adoption among students. I saw a panic in 2022, 2023 -- like, Oh my God, this can do anything. Or at least there were questions. Can this do everything? How much is my class at risk? Now I think there's more of a sense of, Well, this thing still exists, but we have time. We don't have to worry about it right away. And that might actually be a worse reaction than the original. Lila: The blind-spot language rings true to the high-school environment too. I spoke to some high schoolers -- granted this was quite a small sample -- but basically it sounds like everybody is using this all the time for everything. Ian: Not just for school, right? Anything they want to do, they're asking ChatGPT now. Lila: I was a sophomore in college when ChatGPT came out, so I witnessed some of this firsthand. There was much more anxiety -- it felt like the rules were unclear. And I think both of our stories touched on the fact that for this incoming class of high-school and college seniors, they've barely had any of those four years without ChatGPT. Whatever sort of stigma or confusion that might have been there in earlier years is fading, and it's becoming very much default and normalized. Ian: Normalization is the thing that struck me the most. That is not a concept that I think the teachers have wrapped their heads around. Teachers and faculty also have been adopting AI carefully or casually -- or maybe even in a more professional way, to write articles or letters of recommendation, which I've written about. There's still this sense that it's not really a part of their habit. Lila: I looked into teachers at the K-12 level for the article I wrote. Three in 10 teachers are using AI weekly in some way. Ian: Some kind of redesign of educational practice might be required, which is easy for me to say in an article. Instead of an answer, I have an approach to thinking about the answer that has been bouncing around in my brain. Are you familiar with the concept in software development called technical debt? In the software world, you make the decision about how to design or implement a system that feels good and right at the time. And maybe you know it's going to be a bad idea in the long run, but for now, it makes sense and it is convenient. But you never get around to really making it better later on, and so you have all these nonoptimal aspects of your infrastructure. That's the state I feel like we're in, at least in the university. It's a little different in high school, especially in public high school, with these different regulatory regimes at work. But we accrued all this pedagogical debt, and not just since AI -- there are aspects of teaching that we ought to be paying more attention to or doing better, like, this class needs to be smaller, or these kinds of assignments don't work unless you have a lot of hands-on iterative feedback. We've been able to survive under the weight of pedagogical debt, and now something snapped. AI entered the scene and all of those bad or questionable -- but understandable -- decisions about how to design learning experiences are coming home to roost. Lila: I agree that AI is a breaking point in education. One answer that seems to be emerging at the high-school level is a more practical, skills-based education. The College Board, for instance, has announced two new AP courses -- AP Business and AP Cybersecurity. But there's another group of people who are really concerned about how overreliance on these tools erodes critical-thinking skills, and maybe that means everyone should go read the classics and write their essays in cursive handwriting. Ian: My young daughter has been going to this set of classes outside of school where she learned how to wire an outlet. We used to have shop class and metal class, and you could learn a trade, or at least begin to, in high school. A lot of that stuff has been disinvested. We used to touch more things. Now we move symbols around, and that's kind of it. I wonder if this all-or-nothing nature of AI use has something to do with that. If you had a place in your day as a high-school or college student where you just got to paint, or got to do on-the-ground work in the community, or apply the work you did in statistics class to solve a real-world problem -- maybe that urge to just finish everything as rapidly as possible so you can get onto the next thing in your life would be less acute. The AI problem is a symptom of a bigger cultural illness, in a way. Lila: Students are using AI exactly as it has been designed, right? They're just making themselves more productive. If they were doing the same thing in an office, they might be getting a bonus. Ian: Some of the students I talked to said, Your boss isn't going to care how you get things done, just that they get done as effectively as possible. And they're not wrong about that. Lila: One student I talked to said she felt there was really too much to be done, and it was hard to stay on top of it all. Her message was, maybe slow down the pace of the work and give students more time to do things more richly. Ian: The college students I talk to, if you slow it all down, they're more likely to start a new club or practice lacrosse one more day a week. But I do love the idea of a slow-school movement to sort of counteract AI. That doesn't necessarily mean excluding AI -- it just means not filling every moment of every day with quite so much demand. But you know, this doesn't feel like the time for a victory of deliberateness and meaning in America. Instead, it just feels like you're always going to be fighting against the drive to perform even more.

[2]

Confusing school AI policies leave families guessing

Why it matters: Murky policies risk widening inequities and undermining trust, even as most educators agree that AI is here to stay. By the numbers: The Trump administration's push to expand AI in schools, coupled with an ed tech gold rush, has districts revising rules in real time. * 89% of high school and college students say they use AI technology for school, according to recent polling from learning platform Quizlet. That's up from 77% in 2024. * The average teacher is using around 150 different ed tech tools in a given school year, Arman Jaffer, founder of classroom AI assistant Brisk Teaching, told Axios. Between the lines: This is the fourth school year that students have had access to ChatGPT on personal devices, but many districts still don't allow it on school devices. * OpenAI's policies forbid those under 13 from using ChatGPT and require users 13 to 18 to get parent or guardian permission. (Anthropic's Claude chatbot, which is popular among college students and educators, requires users to be 18 or older.) * Regardless of policies and rules, there's no way to stop kids from using ChatGPT on their personal devices, many educators told Axios. The big picture: Parents and students still aren't sure whether using AI tools counts as cheating or digital literacy. * It can be both, says David Touretzky, a Carnegie Mellon computer science professor and founder of AI4K12, an initiative to develop national guidelines for AI education. * "Schools that are already stressed want to ban ChatGPT because they don't know how to cope with it right now," Touretzky told Axios in an email. * Districts with more resources can experiment with new tools -- but some students everywhere will still try to cheat if they can get away with it, Touretzky said. The intrigue: Sal Khan, founder of Khan Academy and the AI tutor and teaching assistant Khanmigo, told Axios that teachers falsely accusing students of cheating is a growing problem. * Khan said a family member was writing assignments and then using AI to introduce errors into their work so that their teacher's AI detector wouldn't flag it as AI-generated. Reality check: Rachel Yurk, chief information and technology officer at the Pewaukee School District in Wisconsin, told Axios her district blocks AI tools on all school-owned student devices, but it's not pretending the tools don't exist. * Since 2022 the district has been teaching students about chatbots -- including bias, privacy, accuracy, emotional dependency and other problems with generative AI. What they're saying: Educators know that students are using chatbots to complete homework. "We're not putting our heads in the sand," Katherine Goyette, computer science coordinator at the California Department of Education, told Axios. * Calling it cheating, Yurk says, is misunderstanding the problem that her district is trying to solve through conversations about responsible use and academic integrity. * Cheating is taking someone else's work and calling it your own, Yurk says, which gets complicated when you're talking about AI: "There's no person behind it, right?" * If you're not watching a student do the work, Khan says, you should assume AI is involved. The solution for many schools will be to change the way teachers assess student proficiency, opting for more in-class writing assignments, oral assessments, class discussions and group work. * These techniques aren't new, Clay Shirky wrote in a recent New York Times op-ed: "They are simply a return to an older, more relational model of higher education." * "Educators at all levels are having to rethink how we should create assignments and how we can accurately measure student learning," Touretzky says. "We'll figure it out eventually," but "banning LLMs is not a realistic solution." What we're watching: Administrators say that the tech is moving too fast to cement rules into place.

[3]

From fear to fascination: How AI is changing Minnesota classrooms

Plus, Anoka-Hennepin schools instructional technology coordinator Justin Wewers adds, "If we're not talking about it as educators to students, then who is?" State of play: As recently as two years ago, a handful of Twin Cities school districts banned generative artificial intelligence tools, and many treated them as threats, said Padrnos. * But last summer, "the tide really shifted" as schools leaned into the "pivotal moment" facing education. What they're saying: It's a big adjustment. One St. Paul Public Schools teacher summed it up to district administrator Phil Wacker: "I want to use this all day every day... and I want to go live in a cabin in the woods with no technology." How it's being used: AI tools can rewrite tests, convert texts to an easier reading level or create a grading rubric -- and that's just a short list of potential teacher time-savers. * One choir director used AI-generated art to help his students memorize their music, said Wewers. * Students can use tools like NotebookLM to create custom study guides -- even in podcast form -- and chatbots to critique their writing. Friction point: While cheating tops many parents' and educators' list of AI fears, teachers have tools to mitigate AI-driven cheating. * They can lock students out of other browser tabs while taking a test, use AI detection software ... or revert to good ol-fashioned paper and pencil. Yes, but: Those countermeasures aren't foolproof. Research has found AI detectors are "easily gamed" and are especially unreliable when the human writer's first language isn't English, Wacker notes. Zoom out: More than cheating, what most worries Padrnos, an Osseo schools administrator, are the elements of AI that schools can't control. * Data entered into Gemini or Copilot through an official school account is generally secure -- but other AI companies are still essentially startups: "Are they going to be here two years from now?" Padrnos asks. * Wacker worries about AI's tendency to reflect the biases of the humans who created it. When prompted to depict suburban vs. urban schools, he's seen AI paint two very different pictures -- one chaotic, disordered, and populated by students of color; the other orderly, and filled with white faces. Between the lines: Even the most enthusiastic "early adopter" schools nationwide are "still piloting AI strategies, not scaling them," according to a recent report from the Center for Reinventing Public Education. * They're also concerned about a lack of sustainable funding or quality training for staff, the academic think tank found. The bottom line: AI has changed the world, and schools will have to figure out how to teach in it. Teachers know it won't be easy.

[4]

Analyzing the pros and cons of AI in NYC schools. Here's what experts say for the new school year.

Doug Williams has been reporting and anchoring in the Tri-State Area since 2013. Artificial intelligence is everywhere, including in classrooms and schools. And it's not just students who are using it. A growing number of teachers, principals and administrators are, as well. As part of CBS News New York's back-to-school series this week, education reporter Doug Williams spoke to experts about the uses -- and risks -- of AI in education. Last September, David Banks closed his final state-of-our-schools address as chancellor by embracing a once-taboo topic in public education. "AI can analyze in real time all the work our children are doing in school," Banks said. Less than a year later, AI is all over the place, and keeping it out of classrooms is unrealistic, if not impossible. That's why schools like United Charter High School for the Humanities II in the Bronx have decided that embracing the technology is the only way to safely corral it. "Because I'm not fluent in all languages that students might speak, I have the opportunity, through AI, to create individual slides," visual arts teacher Marquitta Pope said. "There's a huge opportunity to save time for teachers and prepare kids for college and career," Principal David Neagley said. "Part of being college- and career-ready in our world is making sure they know how to write an effective prompt." The charter school created its own AI policy -- what's allowed and what's not -- for both teachers and students. AI is, after all, designed to sound human. So how do teachers know if humans wrote the papers they're grading? "Students are very innovative. They're always finding ways around it," said Alon Yamin, co-founder and CEO of Copyleaks, an AI-detection software company used by more than 300 educational institutions to detect AI and plagiarism in students' work. You'll never guess the technology used to do it. "It's AI fighting AI. In the end, as humans, it's almost impossible to detect the difference," Yamin said. "Our models are able to detect it." CBS News New York put the technology to the test. Williams asked ChatGPT to write a 1,000-word essay on the impact of the Cuban missile crisis, as an 11th grader would. He even asked it to make some spelling and grammar errors. He then pasted it into Copyleaks, and the tech ruled the essay was 100% AI content. And of that AI content, 48.7% was plagiarism within AI. New York City Schools Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos' predecessor may have embraced the technology, but she is now tasked with handling it responsibly. "We're streamlining all of those supports and taking inventory," Aviles-Ramos said. Williams asked her if schools are able to come up with their own policy or if the system will come up with one overarching policy. "We are. This is why we have an advisory council," Aviles-Ramos said. "There needs to be central guidance." In the meantime, if parents have questions about the role AI plays in their child's school, the chancellor suggests they ask administrators how AI is being used by teachers and students in class, what guardrails are in place, and if the use of AI is in line with data privacy regulations.

[5]

How teachers say they're embracing AI in the classroom

How teachers say they're embracing AI in the classroom Teachers say they are learning to work with AI, not against it. Artificial intelligence is no longer just a buzzword, it's becoming part of daily life in American classrooms. While some schools initially banned tools like ChatGPT over fears of cheating and plagiarism, many educators are now taking a different approach: teaching students how to use AI responsibly, critically and creatively. On Tuesday, amid the start of the new school year, first lady Melania Trump announced the Presidential AI Challenge for educators and students in grades K-12. The challenge is designed to "inspire young people and educators to create AI-based innovative solutions to community challenges while fostering AI interest and competency," according to the White House. "Students and educators of all backgrounds and expertise are encouraged to participate and ignite a new spirit of innovation as we celebrate 250 years of independence and look forward to the next 250 years," the initiative's website reads. "The Presidential AI Challenge will foster interest and expertise in AI technology in America's youth. Early training in the responsible use of AI tools will demystify this technology and prepare America's students to be confident participants in the AI-assisted workforce, propelling our Nation to new heights of scientific innovation and economic achievement." From policing to partnering When ChatGPT first gained popularity, Dr. Lily Gates, a high school English teacher based in Dallas, North Carolina, said her focus was on catching students misusing it. "I realized that I was spending more time trying to catch my students using AI than I was giving feedback on their work," Gates told ABC News, adding that at one point, she discovered some students had begun running AI-written essays through "humanizer" apps that added mistakes to make them appear authentic. Rather than doubling down on surveillance, Gates said she decided to rethink how she taught writing and literacy. In her classes, she said she now emphasizes student voice through a method she calls "Say, Seed, Slay," asking students to record their ideas aloud, listen to peers' recordings, and identify the "seed" that will become the foundation of their essay. For revisions, students record screen-shares and voice notes, giving peer feedback in a way that AI can't replicate. "I tell my students that AI may know what happened in chapter six of 'The Great Gatsby,' but it doesn't know them," she said. "It doesn't know their stories, and their stories have the power to shape the world." Teaching critical AI literacy For Daniel Forrester, director of technology integration at Holy Innocents' Episcopal School in Atlanta, Georgia, the real issue isn't whether students use AI, but whether they know how to evaluate and integrate it. "Critical thinking has always been important, but now it's absolutely essential," he told ABC News. "Students have to think about when and how to use AI and then assess what it gives them for accuracy, bias and relevance." Forrester trains educators to shift focus from policing final products to understanding student process. He uses what he calls the "Forrester 4" questions: * What did you use AI for? * What did you put in? * What did you get out? * What did you keep? "That last one is gold," Forrester explained. "It forces students to put their fingerprints on the work, to make it theirs." He also pushed back on the notion that "using AI is cheating." Students have always had outside help from parents, tutors or peers, he said, but now, every student has access to a digital assistant. The key, he argued, is helping students recognize what tasks must remain fully their own and where AI can play a supportive role. Districts experiment with new models At the district level, leaders say they are experimenting with broader frameworks for integrating AI. Bart Swartz, who leads the Center for Reimagining Education at the University of Kansas, said the schools he works with across Kansas are leaning toward curiosity and experimentation rather than fear. "We're hearing more excitement than concern," Swartz told ABC News. "Educators are asking not just how to use AI safely, but how to use it well, in ways that build trust, enhance learning and bring parents along in the process." He said his team uses a "Three Lenses Framework" to guide schools: * True transformation: Rethinking traditional models of teaching and assessment. * Student involvement: Giving students agency as co-creators of learning. * School within a school: Running pilot programs that test new approaches before scaling. Swartz said he's seen creative examples already: elementary schools using AI to personalize after-school programs, middle school teachers tailoring instruction more closely to student needs, and high school students building AI-generated review games from their class notes. "The most important factor is mindset," he said. "When districts embrace change, the work moves forward." Gates, Swartz and Forrester are among the growing cohort of teachers and experts who say that banning AI isn't realistic. Instead, they say schools should be learning to adapt, weaving AI into lessons while reinforcing timeless skills like critical thinking, communication and creativity. For Gates, that means ensuring her students know their voices matter more than any algorithm. For Forrester, it's teaching students to document their process and reflect on what AI adds or takes away. And for Swartz, it's helping districts create conditions for thoughtful, sustainable change. "Ultimately, the goal isn't perfect assignments or perfect policies," Forrester said, "it's students who leave our schools ready for a world where AI collaboration is just part of how work gets done."

[6]

Is AI 'The New Encyclopedia'? As The School Year Begins, Teachers Debate Using The Technology In The Classroom

Enter your email to get Benzinga's ultimate morning update: The PreMarket Activity Newsletter As the school year gets underway, teachers across the country are dealing with a pressing quandary: whether or not to use AI in the classroom. Ludrick Cooper, an eighth-grade teacher in South Carolina, told CNN that he's been against the use of AI inside and outside the classroom for years, but is starting to change his tune. "This is the new encyclopedia," he said of AI. Don't Miss: The same firms that backed Uber, Venmo and eBay are investing in this pre-IPO company disrupting a $1.8T market -- and you can too at just $2.90/share. They Sold Their Last Real Estate Company for Nearly $1B -- Now They're Building the Future of U.S. Industrial Growth There are certainly benefits to using AI in the classroom. It can make lessons more engaging, make access to information easier, and help with accessibility for those with visual impairments or conditions like dyslexia. However, experts also have concerns about the negative impacts AI can have on students. Widening education inequalities, mental health impacts, and easier methods of cheating are among the main downfalls of the technology. "AI is a little bit like fire. When cavemen first discovered fire, a lot of people said, 'Ooh, look what it can do,'" University of Maine Associate Professor of Special Education Sarah Howorth told CNN. "And other people are like, 'Ah, it could kill us.' You know, it's the same with AI." Several existing platforms have developed specific AI tools to be used in the classroom. In July, OpenAI launched "Study Mode," which offers students step-by-step guidance on classwork instead of just giving them an answer. Trending: Kevin O'Leary Says Real Estate's Been a Smart Bet for 200 Years -- This Platform Lets Anyone Tap Into It The company has also partnered with Instructure, the company behind the learning platform Canvas, to create a new tool called the LLM-Enabled Assignment. The tool will allow teachers to create AI-powered lessons while simultaneously tracking student progress. "Now is the time to ensure AI benefits students, educators, and institutions, and partnerships like this are critical to making that happen," OpenAI Vice President of Education Leah Belsky said in a statement. While some teachers are excited by these advancements and the possibilities they create, others aren't quite sold. Stanford University Vice Provost for Digital Education Matthew Rascoff worries that tools like this one remove the social aspect of education. By helping just one person at a time, AI tools don't allow opportunities for students to work on things like collaboration skills, which will be vital in their success as productive members of society. "Great classrooms create a sense of mutual responsibility for everybody's learning," he told CNN. See Also: 7 Million Gamers Already Trust Gameflip With Their Digital Assets -- Now You Can Own a Stake in the Platform Lauren Monaco, a New York City pre-K and kindergarten teacher, also has concerns about the use of AI in the classroom. She sees AI as a crutch that keeps students from actually learning. In her perspective, teaching involves more than just the "transactional information input-output" of AI, she told CNN. For Robin Lake, Arizona State University's Center on Reinventing Public Education director, the increase of AI use is a positive thing because of how prevalent it's become in other areas of our lives. "What are students going to need to be successful in an AI economy once they get out there?" she told CNN. "That's another issue that educators should be grappling with." Read Next: Wealth Managers Charge 1% or More in AUM Fees -- Range's AI Platform Does It All for a Flat Fee (and Could Save You $10,000+ Annually). Book Your Demo Today. Image: Shutterstock Market News and Data brought to you by Benzinga APIs

Share

Share

Copy Link

As AI becomes increasingly prevalent in schools, educators are grappling with its impact on teaching methods, student learning, and academic integrity. This story explores the evolving landscape of AI in education, from initial fears to growing acceptance and integration.

The Rise of AI in Education

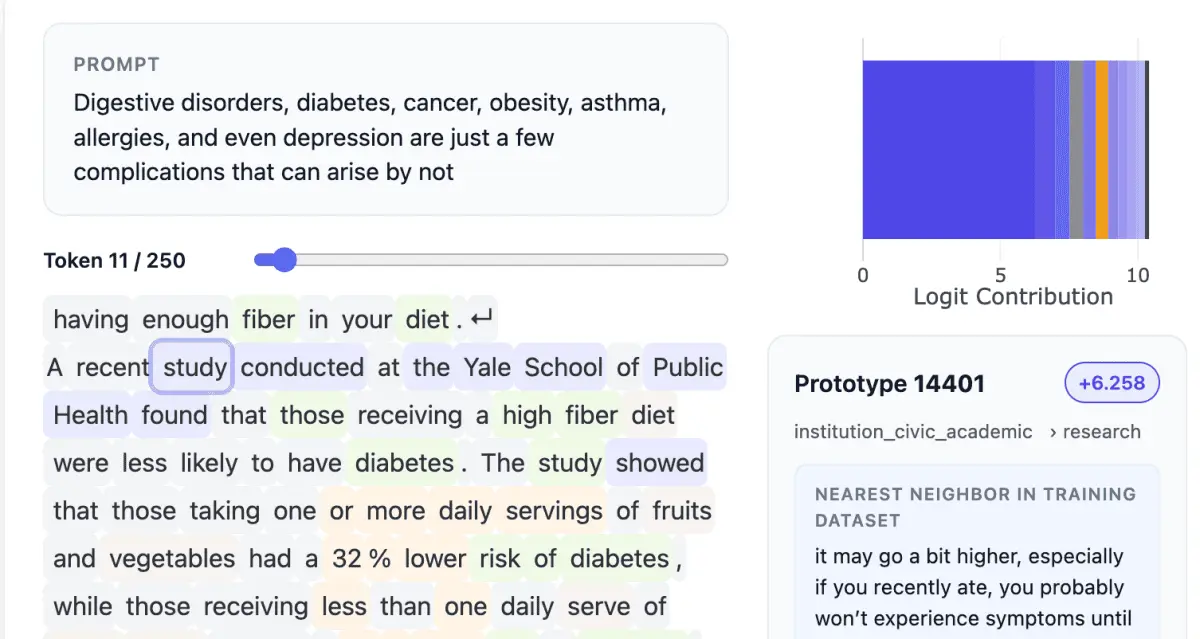

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in education has rapidly transformed the learning landscape over the past few years. Since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, high school and college students have had access to powerful AI tools throughout their academic careers

1

. This widespread adoption has led to significant changes in how students approach their studies and how educators teach and assess learning.Widespread Adoption and Normalization

Recent surveys indicate that 89% of high school and college students now use AI technology for schoolwork, a substantial increase from 77% in 2024

2

. This normalization of AI use has caught many educators off guard, with some still struggling to adapt to the new reality. Ian Bogost, a university professor, notes that while the initial panic has subsided, there may be a dangerous complacency setting in among faculty1

.

Source: CBS

Challenges and Concerns

The rapid integration of AI in education has raised several concerns:

- Academic Integrity: The ease with which students can use AI to complete assignments has led to worries about cheating and plagiarism

3

. - Critical Thinking Skills: There are concerns that overreliance on AI tools may erode students' ability to think critically and independently

1

. - Inequity: Murky policies and inconsistent access to AI tools risk widening educational inequities

2

. - Data Privacy: The use of AI platforms raises questions about the security and privacy of student data

3

.

Adapting Teaching Methods

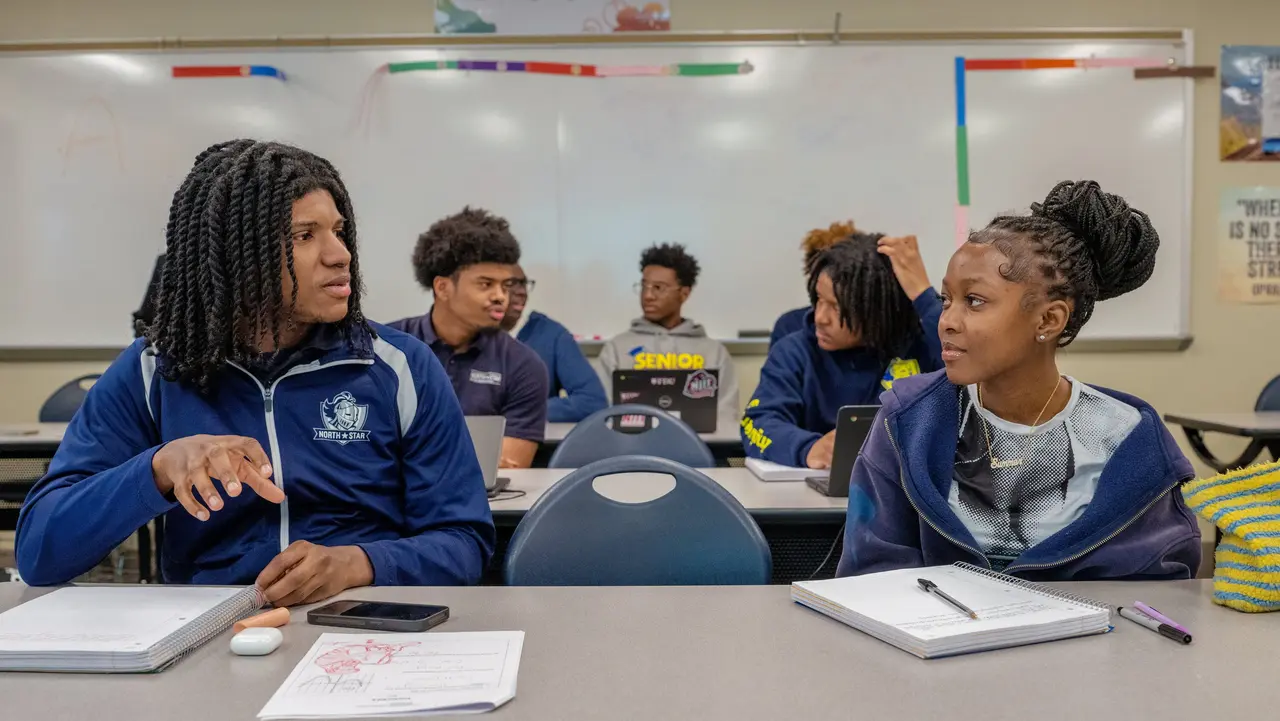

Educators are increasingly recognizing the need to adapt their teaching and assessment methods in response to AI:

- In-class Assessments: Many schools are shifting towards more in-class writing assignments, oral assessments, and group work to ensure authentic student engagement

2

. - AI Literacy: Schools like United Charter High School for the Humanities II in the Bronx are teaching students how to write effective prompts and use AI responsibly

4

. - Process-focused Learning: Some teachers, like Dr. Lily Gates, are emphasizing student voice and the process of writing rather than just the final product

5

.

Source: ABC News

Policy Development

School districts and educational institutions are working to develop comprehensive AI policies:

- Flexible Approaches: Many administrators recognize that the technology is evolving too quickly to cement rigid rules

2

. - Central Guidance: New York City Schools Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos is working on providing centralized guidance while allowing for some school-level flexibility

4

. - Federal Initiatives: The White House has announced the Presidential AI Challenge to foster AI interest and competency among K-12 students and educators

5

.

Related Stories

The Future of AI in Education

As AI becomes an integral part of the educational landscape, several trends are emerging:

- AI as a Tool, Not a Threat: Educators are increasingly viewing AI as a potential asset rather than just a challenge to be overcome

5

. - Emphasis on Critical AI Literacy: Teaching students to evaluate and integrate AI outputs critically is becoming a crucial skill

5

. - Personalized Learning: AI is being used to tailor instruction more closely to individual student needs

5

. - Teacher Time-saving: AI tools are being employed to assist teachers with tasks like creating grading rubrics and converting texts to different reading levels

3

.

Source: Axios

Conclusion

The integration of AI in education represents both a challenge and an opportunity. As Daniel Forrester, an educational technology expert, puts it, "Ultimately, the goal isn't perfect assignments or perfect policies. It's students who leave our schools ready for a world where AI collaboration is just part of how work gets done"

5

. As the educational system continues to adapt, the focus remains on preparing students for a future where AI is an integral part of both learning and working environments.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[4]

Related Stories

AI in Education: Reshaping Learning and Challenging Academic Integrity

12 Sept 2025•Technology

Schools Launch AI Literacy Programs as Chatbots Transform Student Learning Across Classrooms

22 Feb 2026•Technology

AI in Education: Embracing Technology While Navigating Ethical Challenges

14 Nov 2024•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Pentagon Summons Anthropic CEO as $200M Contract Faces Supply Chain Risk Over AI Restrictions

Policy and Regulation

3

Canada Summons OpenAI Executives After ChatGPT User Became Mass Shooting Suspect

Policy and Regulation