AI tools boost individual scientists 3x but shrink science's collective scope, major study reveals

4 Sources

4 Sources

[1]

Artificial intelligence tools expand scientists' impact but contract science's focus - Nature

Although our analysis provides new insight into AI's impact on science, clear limitations remain. Our identification approach -- although validated by experts -- misses subtle and unmentioned forms of AI use, and our focus on natural sciences excludes important domains in which AI adoption patterns may differ. Moreover, despite consistently suggestive evidence, we cannot fully identify the causal linkage between AI adoption and scientific impact. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate that currently attributed uses of AI in science primarily augment cognitive tasks through data processing and pattern recognition. Looking forward, these findings illuminate a critical and expansive pathway for AI development in science. To preserve collective exploration in an era of AI use, we will need to reimagine AI systems that expand not only cognitive capacity but also sensory and experimental capacity49,50, enabling and incentivizing scientists to search, select and gather new types of data from previously inaccessible domains rather than merely optimizing analysis of standing data. The history of major discoveries has been most consistently linked with new views on nature51. Expanding the scope of AI's deployment in science will be required for sustained scientific research and to stimulate new fields rather than merely automate existing ones. In this section we introduce the procedure of selecting the research papers included in our analysis. We conduct our major analyses on OpenAlex -- a scientific research database built on the foundation of the Microsoft Academic Graph (MAG). Supported by non-profit organizations, OpenAlex is continuously updated, providing a sustainable global resource for research information. As of March 2025, OpenAlex contains 265.7 million research papers, along with related data about citation, author, institution and so on. Among the massive quantity of papers in the OpenAlex dataset, we select 66,117,158 English research papers published in journals and conferences spanning from 1980 to 2025 and filter out those with incomplete titles or abstracts. We identify the scientific discipline each paper belongs to by making use of the topics noted in OpenAlex, which are extracted using a natural language processing approach that annotates titles and abstracts with Wikipedia article titles as topics sharing textual similarity. In the raw dataset, these topics form a hierarchical structure and each paper is associated with several. Adopting the 19 basic scientific disciplines in MAG, that is, art, biology, business, chemistry, computer science, economics, engineering, environmental science, geography, geology, history, materials science, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, physics, political science, psychology, and sociology, we trace along the hierarchy and determine to which disciplines each topic belongs. We note that because the original topics of one paper may be retraced to different topics, the scientific discipline of each paper may not be unique. In other words, one paper may span two or more academic disciplines, for example, chemistry and biology, which reflects the common phenomena of borderline or interdisciplinary research. Here we emphasize the adoption of AI methods in conventional natural science disciplines and exclude research developing AI methodologies themselves, separating the influence of AI on science from AI's own invention and refinement. We therefore select biology, medicine, chemistry, physics, materials science and geology as representatives of natural science disciplines, but exclude computer science and mathematics, where most works introducing and developing AI methods are published. We also exclude art, business, economics, history, philosophy, political science, psychology and sociology to focus on how AI is changing the natural sciences and career trajectories in those sciences. Our six natural science disciplines include the majority of OpenAlex articles, resulting in 41,298,433 papers, containing 18,392,040 in biology, 4,209,771 in chemistry and 2,380,666 in geology, 4,755,717 in materials science, 24,315,342 in medicine and 5,138,488 in physics. The selected disciplines cover various dimensions of natural science, representing a broad view of scientific research as a whole. We divide the history of AI development into three key eras: the traditional machine learning era (1980-2014), the deep learning era (2015-2022) and the generative AI era (2023 to present). We consider 1980 as the start of the traditional machine learning era because several landmark works were published in the 1980s, such as the back-propagating method. We regard the deep learning era to have begun in 2015, as indicated by breakthroughs such as ResNet, which enabled the training of ultra-deep neural networks, revolutionizing fields such as computer vision and speech recognition. Finally, we define the generative AI era as beginning in 2023, following the publication of ChatGPT -- the first widely used large language model -- in December 2022. This marked the advent of large-scale transformer-based models capable of strong generalized performance across a wide range of tasks, sparking new applications in natural language processing and beyond. Each of these transitions was driven by advances in algorithms, computational power and data availability, substantially expanding the capabilities and scope of AI for science. Insofar as both a paper's title and abstract contain important information about its content, we independently train two separate models on the basis of paper titles and abstracts, and then integrate the two models into an ensembled one by averaging their outputs. The structure of our natural language processing model for paper identification consists of two parts. The backbone network is a twelve-layer BERT model with twelve attention heads in each layer, and the sequence classification head is a linear layer with a two-dimensional output atop the BERT output. We normalize the two-dimensional output with a softmax function and obtain the probability that the paper involves AI-assistance. We use the BERT model called BERT-base-uncased from Hugging Face, which is pre-trained with a large-scale general corpus, and set the maximum length of tokenization to be 16 for titles and 256 for abstracts. We design a two-stage fine-tuning process with training and validation sets, which we extracted from the OpenAlex dataset, to transfer the pre-trained model to our paper identification task. The construction of positive and negative data is different between the two stages. In both stages, we randomly split the positive and negative data into 90% and 10% sets, which correspond to training and validation sets, respectively. We use the training set for model training and use the validation set to select the optimal model. As the numbers of positive and negative cases are unbalanced, we use the bootstrap sample technique on positive cases to balance its number with negative cases at both stages. In the first stage, we construct relatively coarse positive data, only considering eight typical AI journals and conferences, including Nature Machine Intelligence, Machine Learning, Artificial Intelligence, Journal of Machine Learning Research (JMLR), International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) and the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI). Among the papers belonging to our chosen six disciplines, we extract all papers published in these venues as positive cases and randomly sample 1% of the remaining papers in our six chosen natural science fields as negative cases, resulting in 26,165 positive and 291,035 negative cases. We fine-tune the pre-trained model for 30 epochs on the training set and select the optimal model according to the F1-score on the validation set. In the second stage, we construct more precise positive data on the basis of the optimal model obtained in the first stage. We identify papers in the whole OpenAlex dataset and aggregate the results for each venue, obtaining the probability that each venue in OpenAlex is an AI venue by averaging the AI probability for all papers within it. We then select the venues with >80% AI probability and >100 papers as AI venues. We also incorporate venues with 'machine learning' or 'artificial intelligence' in their names. In papers belonging to our six chosen disciplines, we extract all papers published in the selected AI venues as positive cases and randomly sample 1% of those remaining as negative cases, resulting in 31,311 positive and 231,258 negative cases. We then fine-tune the obtained optimal model in the first stage for another 30 epochs with the new training set and select the best model according to F1-score on the new validation set. Finally, we use optimal ensemble models during both stages to identify all papers that use AI to support natural science research from the selected representative natural science disciplines. We arbitrarily sample 220 papers (110 papers × 2 groups) from each of the six disciplines, resulting in twelve paper groups in total. We enlisted twelve experts with abundant AI research experience (Supplementary Table 1) and assigned three different groups of papers to each. Without revealing the classification results obtained from the BERT model, we queried our experts on whether each paper was an AI paper. In this way, each paper is repeatedly labelled by three distinct experts, and we evaluate the consistency among these experts on the basis of Fleiss's κ (refs. ), which is an unsupervised measurement for assessing the agreement between independent raters. Having confirmed consensus among our experts, we draw the final expert label of each paper from the three experts according to the principle of the minority obeying the majority. We regard the expert labels as ground truth and validate the result of our BERT model against them with the F1-score, which is a supervised measurement of accuracy. Here we define the project leader as the last author of a research paper, in alignment with conventions established by previous studies. To ensure that in most papers, the last author represents the project leader, we examine the fraction of papers that list authors following alphabetical order. First, we directly traverse all selected papers and obtain the prevalence of papers listing authors in alphabetical order, which ranges from 14.87% in materials science to 22.15% in geology. Nevertheless, it is difficult to distinguish whether these papers actually intended to list the authors in alphabetical order or according to their roles, which unintentionally fall in alphabetical order. The latter situation is more likely to occur when there are fewer authors (two or three). To tackle this analytical challenge, we determine the fraction of unintended alphabetical author lists through a Monte Carlo method. We generate ten randomly shuffled copies of the author list for each paper and find that from 13.82% (materials science, σ = 0.02) to 20.28% (geology, σ = 0.03) of papers have alphabetically listed authors among the random author lists. This indicates the proportion of 'unintended' alphabetical author lists, and we can derive the actual fraction of papers with intentionally alphabetical author lists by the difference between the above two sets of statistical results. The actual fraction obtained illustrates that only 1.58% of papers across all disciplines intentionally list the authors in alphabetical order (Supplementary Table 12) and therefore, we can, with negligible interference, assume that we can identify last authors as team leaders. The OpenAlex dataset incorporates a well-designed author name disambiguation mechanism, which uses an XGBoost model to predict the likelihood that two authors are the same on the basis of features such as their institutions, co-authors and citations, and then applies a custom, ORCID-anchored clustering process to group their works, assigning a unique ID to each author. Simply using unique IDs, we are able to track a large number of authors at the same time, where we depict an individual scientist's career trajectory using a role transition model (Extended Data Fig. 4a) and extract the role transition trajectories for scientists. First we traverse all selected papers in the six disciplines and extract all the scientists involved in any of these papers. Then, for each individual scientist, we extract all papers in which they have been involved and record the time of their first publication in any role, the time of their first publication as team leader (if ever), and the time of their last publication. We then filter out scientists whose publication records span only a single year. We also filter out those who directly start as established scientists leading research teams without a role transition from junior scientists. Finally, we detect the time that each scientist abandons academic publishing. Considering that one scientist may not publish papers continuously every year, we cannot regard them as having left academia on the basis of their absence in the published record for a single year. We therefore follow the settings used in previous work to use a threshold of three years and regard scientists who have no more publications after 2022 as having exited academia, whereas those who still publish papers after 2022 are considered to have an unclear ultimate status and are excluded from the analysis. Finally, we obtain 2,282,029 scientists in the six disciplines with complete role transition trajectories. We also classify them into AI and non-AI scientists according to whether they have published AI-augmented papers. Moreover, by analysing author contribution statements collected in previous studies, we further validate our detection results by examining changes in scientists' self-reported contributions throughout their careers (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Results indicate that junior scientists primarily engage in technical tasks, such as conducting experiments and analysing data, and less in conceptual tasks, such as conceiving ideas and writing papers. Nevertheless, the proportion of conceptual work significantly rises (P < 0.01 and df = 1 in a Cochran-Armitage test) during their tenure as junior scientists, reaching saturation at a high level (60% or more) on transition to becoming established scientists. This finding validates our definition of role transition by demonstrating a shift in the nature of scientists' contributions from participating in research projects to leading them. To obtain a more precise quantification of how much AI accelerates the career development of junior scientists, we use a general birth-death model. This type of stochastic process model depicts the dynamic evolution of a population as members join and exit. In our context, it models the role transitions of junior scientists. Specifically, we use two separate birth-death models for junior scientists who eventually become established and for those who leave academia, respectively. Here, 'birth' processes refer to the entry of junior scientists into academic publishing, and 'death' processes symbolize their transition out of the junior stage, either by becoming established scientists or quitting academia. As the entry and exit of each junior scientist are independent from one another, we use Poisson processes to model 'birth' (entry) and 'death' (exit) events, respectively. The Poisson process is a typical stochastic process model for describing the occurrence of random events that are independent of each other. The mathematical formula of the Poisson process is: where N(t) denotes the number of random events that happened before time t, and λ is the parameter of the Poisson process, depicting the happening rate of random events. We consider a birth-death model in which birth and death dynamics are both Poisson processes, and rate parameters are μ and ω, respectively. Through mathematical derivation, we conclude that the duration time t from birth to death follows an exponential distribution with the parameter ω - μ, where the exact form of the probability density function is: We consider the difference between the two rate parameters ω - μ as a whole and fit it with a single parameter λ. The transition time for junior scientists to become established scientists or leave academia then follows the exponential distribution: and the corresponding survival function is Hence the average transition time is the conditional expectation of the distribution defined as follows: We fit the role transition time of scientists with the aforementioned exponential distribution, thereby determining the respective values of λ for AI-adopting junior scientists and their non-AI counterparts. Guided by the underlying mechanism of junior scientists' career development incorporated within the birth-death model, expectations from the model offer a more accurate estimate of the average role transition time. To assess the knowledge extent of a set of research papers within their high-dimensional embeddings we first compute the centroid as the mean of their vector locations: Next, we compute the Euclidean distance from each embedding to the centroid, where the knowledge extent (KE) of the set of papers is defined as the maximum distance or 'diameter' of the vector space covered: We note that Euclidean distance is highly correlated with the cosine and related angular distances. In practice, the number of AI and non-AI papers in each domain differs considerably, introducing bias to the measurement of knowledge extent. To address this issue, we build on past work about cognitive extent, which is a measure of the breadth of a scientific field's cognitive territory, and is quantified by the number of unique phrases -- as a proxy for scientific concepts -- found within a sampled batch of papers of a given size. For each domain, we randomly sample 1,000 papers from both AI and non-AI categories, compute their respective knowledge extent, and repeat this process 1,000 times. By comparing knowledge extent values across these 1,000 random samples, we ensure that the number of AI and non-AI papers is balanced, making our knowledge extent results comparable. To measure how much knowledge space can be derived from each original paper, we calculate the knowledge extent of 'paper families', that is, a focal paper and its follow-on citations. Focusing on an original research paper ϕ, which corresponds to a high-dimensional embedding vector , we extract all n research papers that cite this original paper. These papers are sorted chronologically by publication date, from earliest to most recent. The corresponding high-dimensional embeddings of these sorted papers are: Thereby, we calculate knowledge extent covered by the 'paper family' consisting of the original paper ϕ and the first n follow-on papers, citing it (1 ≤ n ≤ n) as: To quantify how frequently citations of the same original paper interact with each other, we design a metric called follow-on engagement, building on previous work. For an original paper with n citations, there are at most possible citations among these n citing papers if everyone cites all papers published earlier than their own. We then count how many times these n citing papers actually cite one another, denoted as k. Our metric for follow-on engagement (EG) is calculated as the ratio of actual to maximum possible citations: This metric helps quantify the degree of interactions and collaboration among papers that cite the same original work. Past work has demonstrated a positive association between the ambiguity of a focal work and follow-on engagement. Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

[2]

Are Scientists Sacrificing Originality for Speed With the Use of AI?

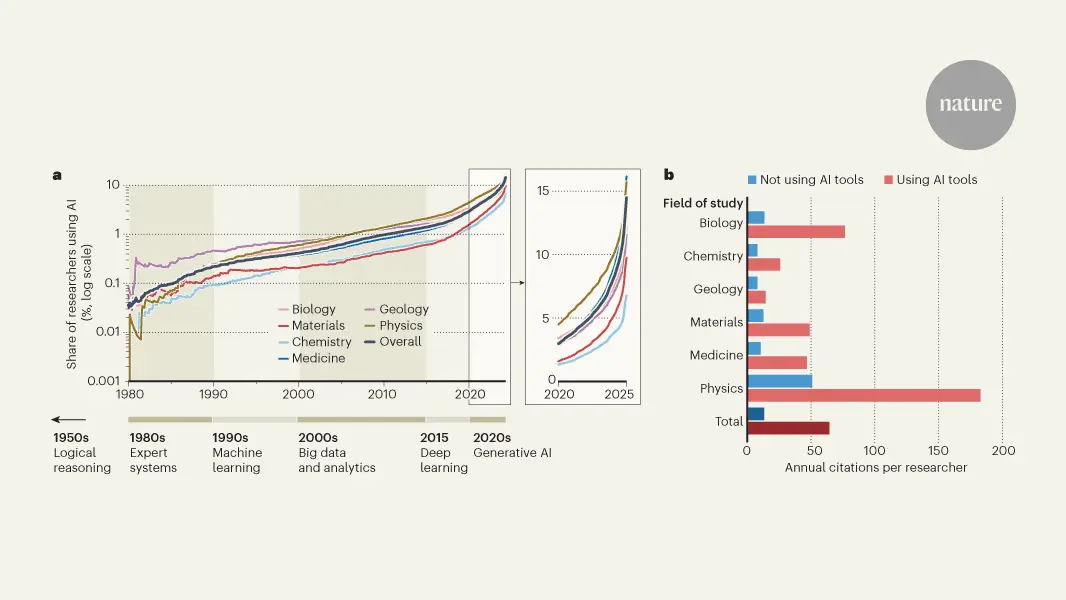

New analysis suggests AI tools narrow the span of ideas explored AI is turning scientists into publishing machines -- and quietly funneling them into the same crowded corners of research. That's the conclusion of an analysis of more than 40 million academic papers, which found that scientists who use AI tools in their research publish more papers, accumulate more citations, and reach leadership roles sooner than peers who don't. But there's a catch. As individual scholars soar through the academic ranks, science as a whole shrinks its curiosity. AI-heavy research covers less topical ground, clusters around the same data-rich problems, and sparks less follow-on engagement between studies. The findings highlight a tension between personal career advancement and collective scientific progress, as tools such as ChatGPT and AlphaFold seem to reward speed and scale -- but not surprise. "You have this conflict between individual incentives and science as a whole," says James Evans, a sociologist at the University of Chicago who led the study. And as more researchers pile onto the same scientific bandwagons, some experts worry about a feedback loop of conformity and declining originality. "This is very problematic," says Luís Nunes Amaral, a physicist who studies complex systems at Northwestern University. "We are digging the same hole deeper and deeper." Evans and his colleagues published the findings January 14 in the journal Nature. For Evans, the tension between efficiency and exploration is familiar terrain. He has spent more than a decade using massive publication and citation datasets to quantify how ideas spread, stall, and sometimes converge. In 2008, he showed that the shift to online publishing and search made scientists more likely to read and cite the same highly visible papers, accelerating the dissemination of new ideas but narrowing the range of ideas in circulation. Later work detailed how career incentives quietly steer scientists toward safer, more crowded questions rather than riskier, original ones. Other studies tracked how large fields tend to slow their rate of conceptual innovation over time, even as the volume of papers explodes. And more recently, Evans has begun turning the same quantitative lens on AI itself, examining how algorithms reshape collective attention, discovery, and the organization of knowledge. That earlier work often carried a note of warning: The same tools and incentives that make science more efficient can also compress the space of ideas scientists collectively explore. The new analysis now suggests that AI may be pushing this dynamic into overdrive. To quantify the effect, Evans and collaborators from the Beijing National Research Center for Information Science and Technology trained a natural language processing model to identify AI-augmented research across six natural science disciplines. Their dataset included 41.3 million English-language papers published between 1980 and 2025 in biology, chemistry, physics, medicine, materials science, and geology. They excluded fields such as computer science and mathematics that focus on developing AI methods themselves. The researchers traced the careers of individual scientists, examined how their papers accumulated attention, and zoomed out to consider how entire fields clustered or dispersed intellectually over time. They compared roughly 311,000 papers that incorporated AI in some way -- through the use of neural networks or large language models, for example -- with millions of others that did not. The results revealed a striking trade-off. Scientists who adopt AI gain productivity and visibility: On average, they publish 3 times as many papers, receive nearly 5 times as many citations, and become team leaders a year or two earlier than those who do not. But when those papers are mapped in a high-dimensional "knowledge space," AI-heavy research occupies a smaller intellectual footprint, clusters more tightly around popular, data-rich problems, and generates weaker networks of follow-on engagement between studies. The pattern held across decades of AI development, spanning early machine learning, the rise of deep learning, and the current wave of generative AI. "If anything," Evans notes, "it's intensifying." Intellectual narrowing isn't the only unintended consequence either. With automated tools making it easier to mass-produce manuscripts and conference submissions, journal editors and meeting organizers have witnessed a surge in low-quality and fraudulent papers or presentations, often produced at industrial scale. "We've become so obsessed with the number of papers [that scientists publish] that we are not thinking about what it is that we are researching -- and in what ways that contributes to a better understanding of reality, of health, and of the natural world," says Nunes Amaral, who detailed the phenomenon of AI-fueled research paper mills last year. Aside from recent publishing distortions, Evans's analysis suggests that AI is largely automating the most tractable parts of science rather than expanding its frontiers. Models trained on abundant existing data excel at optimizing well-defined problems: predicting protein structures, classifying images, extracting patterns from massive datasets. Some systems have also begun to propose new hypotheses and directions of inquiry -- a glimpse of what some now call an "AI co-scientist." But unless they are deliberately designed and incentivized to do so, such systems -- and the scientists who rely on them -- are unlikely to venture into poorly mapped territories where data are scarce and questions are messier, Evans says. The danger is not that science slows down, but that it becomes more homogeneous. Individual labs may race ahead, while the collective enterprise risks converging on the same problems, methods, and answers -- a high-speed version of the same narrowing Evans first documented when search engines replaced library stacks. "This is a really scary paper to think about in terms of how the second- and third-order effects of using AI in science play out," says Catherine Shea, a social psychologist who studies organizational behavior at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business in Pittsburgh. "Certain types of questions are more amenable to AI tools," she notes. And in an academic environment in which papers are the main currency of success, researchers naturally gravitate toward the problems that are easiest for these tools to crank through and turn into publishable results. "It just becomes this self-reinforcing loop over time," Shea says. Whether this trend persists may depend on how the next generation of AI tools is built and deployed across scientific workflows. In a paper published last month, Bowen Zhou and his colleagues at the Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in China argued that the application of AI in science remains fragmented, with data, computation, and hypothesis-generation tools often deployed in a siloed and task-specific fashion, limiting knowledge transfer and blunting transformative discovery. But when those elements are integrated, AI-for-science systems help expand scientific discover, says Zhou, a machine-learning researcher who previously served as chief scientist of the IBM Watson Group. Perhaps, says Evans. But he doesn't think that the problem is baked into the algorithmic design of AI. More than technical integration, he argues, what may matter most is overhauling the reward structures that shape what scientists choose to work on in the first place. "It's not about the architecture per se," Evans says. "It's about the incentives." Now, says Evans, the challenge is to deliberately redirect how AI is used and rewarded in science: "In some sense, we haven't fundamentally invested in the real value proposition of AI for science, which is asking what it might allow us to do that we haven't done before." "I'm an AI optimist," he adds. "My hope is that this [paper] will be a provocation to using AI in different ways" -- ways that expand the kinds of questions scientists are willing to pursue, rather than simply accelerating work on the most tractable ones. "This is the grand challenge if we want to be growing new fields."

[3]

AI has supercharged scientists -- but may have shrunk science

Analysis of 41 million papers finds that although AI expands individual impact, it narrows collective scientific exploration As artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT gain footholds across companies and universities, a familiar refrain is hard to escape: AI won't replace you, but someone using AI might. A paper published today in Nature suggests this divide is already creating winners and laggards in the natural sciences. In the largest analysis of its kind so far, researchers find that scientists embracing any type of AI -- going all the way back to early machine learning methods -- consistently make the biggest professional strides. AI adopters have published three times more papers, received five times more citations, and reach leadership roles faster than their AI-free peers. But science as a whole is paying the price, the study suggests. Not only is AI-driven work prone to circling the same crowded problems, but it also leads to a less interconnected scientific literature, with fewer studies engaging with and building on one another. "I was really amazed by the scale and scope of this analysis," says Yian Yin, a computational social scientist at Cornell University who has studied the impact of large language models (LLMs) on scientific research. "The diversity of AI tools and very different ways we use AI in scientific research makes it extremely hard to quantify these patterns." These results should set off "loud alarm bells" for the community at large, adds Lisa Messeri, a sociocultural anthropologist at Yale University. "Science is nothing but a collective endeavor," she says. "There needs to be some deep reckoning with what we do with a tool that benefits individuals but destroys science." To uncover these trends, researchers began with more than 41 million papers published from 1980 to 2025 across biology, medicine, chemistry, physics, materials science, and geology. First, they faced a major hurdle: figuring out which papers used AI, a category that spans everything from early machine learning to today's LLMs. "This is something that people have been trying to figure out for years, if not for decades," Yin says. The team's solution was, fittingly, to use AI itself. The researchers trained a language model to scan titles and abstracts and flag papers that likely relied on AI tools, identifying about 310,000 such papers in the data set. Human experts then reviewed samples of the results and confirmed the model was about as accurate as a human reviewer. With that subset of papers, the researchers could then measure AI's impact on the scientific ecosystem. Across the three major eras of AI -- machine learning from 1980 to 2014, deep learning from 2016 to 2022, and generative AI from 2023 onward -- papers that used AI drew nearly twice as many citations per year as those that did not. Scientists who adopted AI also published 3.02 times as many papers and received 4.84 times as many citations over their careers. Benefits extended to career trajectories, too. Zooming in on 2 million of the researchers in the data set, the team found that junior scientists who used AI were less likely to drop out of academia and more likely to become established research leaders, doing so nearly 1.5 years earlier than their peers who hadn't. But what was good for individuals wasn't good for science. When the researchers looked at the overall spread of topics covered by AI-driven research, they found that AI papers covered 4.6% less territory than conventional scientific studies. This clustering, the team hypothesizes, results from a feedback loop: Popular problems motivate the creation of massive data sets, those data sets make the use of AI tools appealing, and advances made using AI tools attract more scientists to the same problems. "We're like pack animals," says study co-author James Evans, a computational social scientist at the University of Chicago. That crowding also shows up in the links between papers. In many fields, new ideas grow through dense networks of papers that cite one another, refine methods, and launch new lines of research. But AI-driven papers spawned 22% less engagement across all the natural sciences disciplines. Instead, they tended to orbit a small number of superstar papers, with fewer than one-quarter of papers receiving 80% of the citations. "When your attention is attracted by star papers like [the protein folding model] AlphaFold, all you're thinking is how you can build on AlphaFold and beat other people to doing it," says Tsinghua University co-author Fengli Xu. "But if we all climb the same mountains, then there are a lot of fields we are not exploring." "Science is seeing a degree of disruption that is rare," says Dashun Wang, who researches the science of science at Northwestern University. The rapid rise of generative AI -- which is reshaping research workflows faster than many scientific institutions can keep up -- only makes the stakes higher and the future shape of science less certain, he says. But the narrowing of science may still be reversible. One way to push back, says Zhicheng Lin, a psychologist at Yonsei University who studies the science of science, is to build better and larger data sets in fields that haven't yet made much use of AI. "We are not going to improve science by forcing a shift away from data-heavy approaches," he says. "A brighter future involves making data more abundant across more domains." Further down the line, future AI systems should also evolve beyond crunching data into autonomous agents capable of scientific creativity, which could expand science's horizons again, says study co-author Yong Li, who studies AI and the science of science at Tsinghua. Until then, Evans says, the scientific community must reckon with how these tools have affected incentives across the board. "I don't think this is how AI has to shape science," he says. "We want a world in which AI-enhanced work, which is getting increased funding and increasing in rate, is generating new fields -- rather than just turning the thumbscrews on old questions."

[4]

AI tools boost individual scientists but could limit research as a whole

Artificial intelligence is influencing many aspects of society, including science. Writing in Nature, Hao et al. report a paradox: the adoption of AI tools in the natural sciences expands scientists' impact but narrows the set of domains that research is carried out in. The authors examined more than 41 million papers, roughly 311,000 of which had been augmented by AI in some way -- through the use of machine-learning methods or generative AI, for example. They find that scientists who conduct AI-augmented research publish more papers, are cited more often and progress faster in their careers than those who do not, but that AI automates established fields rather than supporting the exploration of new ones. This raises questions and concerns regarding the potential impact of AI tools on scientists and on science as a whole.

Share

Share

Copy Link

A groundbreaking analysis of over 41 million academic papers reveals a stark paradox: while artificial intelligence tools help scientists publish three times more papers and gain nearly five times more citations, they're simultaneously narrowing the breadth of scientific inquiry. The study, published in Nature, shows AI-driven research clusters around popular, data-rich problems, creating a tension between individual career advancement and collective scientific progress.

AI Boosts Scientists' Productivity While Narrowing Research Horizons

Artificial intelligence tools are transforming scientific research in ways that benefit individual careers but may harm science as a whole. A comprehensive analysis published in Nature examining over 41 million academic papers reveals that scientists who adopt AI tools publish 3.02 times more papers and receive 4.84 times more citations than their peers who don't use these technologies

1

3

. However, the impact of AI tools on science extends beyond productivity gains. The study found that AI-driven research clusters around the same data-rich problems, covering 4.6% less topical ground than conventional research3

. This creates what researchers call a "conflict between individual incentives and science as a whole," according to James Evans, a sociologist at the University of Chicago who led the study2

.

Source: Nature

Machine Learning to Generative AI: Patterns Across Three Eras

The research team analyzed papers from the OpenAlex database spanning 1980 to 2025, covering biology, medicine, chemistry, physics, materials science, and geology

1

. They divided AI development into three key eras: traditional machine learning (1980-2014), deep learning (2015-2022), and generative AI (2023-present)1

. Across all three periods, the narrowing scope of scientific inquiry remained consistent. The pattern held whether scientists used early machine learning methods, tools like AlphaFold, or ChatGPT and other generative AI systems. Papers that used AI drew nearly twice as many citations per year as those that did not, demonstrating the significant AI impact on individual metrics of success3

.Individual Career Advancement Accelerates With AI Adoption

The benefits for individual scientists extend well beyond publication counts. Researchers who embraced AI reached leadership roles 1.5 years earlier than their peers

3

. Junior scientists who used AI were also less likely to drop out of academia, suggesting these tools provide tangible advantages for career progression3

. The study identified roughly 311,000 papers that incorporated AI in some way through data processing and pattern recognition tasks2

4

. To identify these papers, researchers trained a natural language processing model to scan titles and abstracts, with human experts confirming the model was about as accurate as a human reviewer3

.Collective Scientific Progress Suffers From Feedback Loop of Conformity

While individuals thrive, the broader scientific enterprise faces concerning trends. AI-driven research spawned 22% less engagement across natural sciences disciplines, with papers tending to orbit a small number of superstar papers rather than forming dense networks of interconnected ideas

3

. "We are digging the same hole deeper and deeper," warns Luís Nunes Amaral, a physicist at Northwestern University2

. The researchers hypothesize this clustering results from a feedback loop: popular problems motivate the creation of massive datasets, those datasets make AI tools appealing, and advances made using AI attract more scientists to the same problems3

. This feedback loop of conformity threatens research originality and intellectual breadth.

Source: IEEE

Related Stories

Automating Established Fields Rather Than Exploring New Frontiers

The findings demonstrate that currently attributed uses of AI in scientific research primarily augment cognitive tasks through data processing and pattern recognition, automating established fields rather than supporting the exploration of new ones

1

4

. "When your attention is attracted by star papers like AlphaFold, all you're thinking is how you can build on AlphaFold and beat other people to doing it," explains Tsinghua University co-author Fengli Xu. "But if we all climb the same mountains, then there are a lot of fields we are not exploring"3

. The study suggests that to preserve collective exploration, the scientific community will need to reimagine AI systems that expand not only cognitive capacity but also sensory and experimental capacity, enabling scientists to search and gather new types of data from previously inaccessible domains1

.Future Implications for Science and AI Development

Experts warn that these trends could intensify as generative AI reshapes research workflows faster than scientific institutions can adapt. "Science is seeing a degree of disruption that is rare," notes Dashun Wang, who researches the science of science at Northwestern University

3

. Lisa Messeri, a sociocultural anthropologist at Yale University, argues these results should set off "loud alarm bells" for the community. "Science is nothing but a collective endeavor," she says. "There needs to be some deep reckoning with what we do with a tool that benefits individuals but destroys science"3

. The history of major discoveries has been most consistently linked with new views on nature, suggesting that expanding the scope of AI's deployment in science will be required for sustained scientific research and to stimulate new fields1

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

Related Stories

AI in Scientific Research: Boosting Citations but Raising Equity Concerns

12 Oct 2024•Science and Research

AI's Double-Edged Sword: Revolutionizing Scientific Research While Raising Ethical Concerns

06 Jan 2025•Science and Research

AI in Science: A Double-Edged Sword - Advancing Research While Fueling Misconduct

20 Mar 2025•Science and Research

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Meta strikes up to $100 billion AI chips deal with AMD, could acquire 10% stake in chipmaker

Technology

3

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with supply chain risk label over AI safeguards for military use

Policy and Regulation