Anthropic's Claude Code sparks AI race as developers build apps in hours without traditional coding

4 Sources

4 Sources

[1]

AI's Biggest Moment Since ChatGPT

Over the holidays, Alex Lieberman had an idea: What if he could create Spotify "Wrapped" for his text messages? Without writing a single line of code, Lieberman, a co-founder of the media outlet Morning Brew, created "iMessage Wrapped" -- a web app that analyzed statistical trends across nearly 1 million of his texts. One chart that he showed me compared his use of lol, haha, 😂, and lmao -- he's an lol guy. Another listed people he had ghosted. Lieberman did all of this using Claude Code, an AI tool made by the start-up Anthropic, he told me. In recent weeks, the tech world has gone wild over the bot. One executive used it to create a custom viewer for his MRI scan, while another had it analyze their DNA. The life optimizers have deployed Claude Code to collate information from disparate sources -- email inboxes, text messages, calendars, to-do lists -- into personalized daily briefs. Though Claude Code is technically an AI coding tool (hence its name), the bot can do all sorts of computer work: book theater tickets, process shopping returns, order DoorDash. People are using it to manage their personal finances, and to grow plants: With the right equipment, the bot can monitor soil moisture, leaf temperature, CO, and more. Some of these use cases likely require some preexisting technical know-how. (You can't just fire up Claude Code and expect it to grow you a tomato plant.) I don't have any professional programming experience myself, but as soon as I installed Claude Code last week, I was obsessed. Within minutes, I had created a new personal website without writing a single line of code. Later, I hooked the bot up to my email, where it summarized my unread emails, and sent messages on my behalf. For years, Silicon Valley has been promising (and critics have been fearing) powerful AI agents capable of automating many aspects of white-collar work. The progress has been underwhelming -- until now. Read: Was Sam Altman right about the job market? This is "bigger" than the ChatGPT moment, Lieberman wrote to me. "But Pandora's Box hasn't been opened for the rest of the world yet." Claude Code has seemingly yet to take off outside Silicon Valley: Unlike ChatGPT, Claude Code can be somewhat intimidating to set up, and the cheapest version costs $20 a month. When Anthropic first released the bot in early 2025, the company explicitly positioned it as a tool for programmers. Over time, others in Silicon Valley -- product managers, salespeople, designers -- started using Claude Code, too, including for noncoding tasks. "That was hugely surprising," Boris Cherny, the Anthropic employee who created the tool, told me. The bot's popularity truly exploded late last month. A recent model update improved the tool's capabilities, and with a surplus of free time over winter break, seemingly everyone in tech was using Claude Code. "You spent your holidays with your family?" wrote one tech-policy expert. "That's nice I spent my holidays with Claude Code." (On Monday, Anthropic released a new version of the product called "Cowork" that's designed for people who aren't developers, but for now it's only a research preview and is much more expensive.) I can see why the tech world is so excited. Over the past few days, I've spun up at least a dozen projects using the bot -- including a custom news feed that serves me articles based on my past reading preferences. The first night I installed it, I stayed up late playing with the tools, sleeping only after maxing out my allowed usage for the second time that evening. (Anthropic limits usage.) The next morning, I maxed it out again. When I told a friend to try it out, he was skeptical. "It sounds just like ChatGPT," he told me. The next day he texted with a gushing update: "It just DOES stuff," he said. "ChatGPT is like if a mechanic just gave you advice about your car. Claude Code is like if the mechanic actually fixed it." Part of what works so well about Claude Code is that it makes it easy to connect all sorts of apps. Sara Du, the founder of the AI start-up Ando, told me that she is using it to help with a variety of life tasks, like managing her texts with real-estate agents. Because the bot is hooked up to her iMessages, she can ask it to find all of the Zillow links she's sent over the past month and compile a table of listings. "It gives me a lot of dopamine," Du said. Andrew Hall, a Stanford political scientist, had Claude Code analyze the raw data of an old paper of his studying mail-in voting. In roughly an hour, the bot replicated his findings and wrote a full research paper complete with charts and a lit review. (After a UCLA Ph.D. student performed an audit of the bot's paper, he and Hall offered a "subjective conclusion": Claude Code made only a few minor errors, the kind that a human might make.) "It certainly was not perfect, but it was very, very good," Hall told me. AI is not yet a substitute for an actual political-science researcher, but he does think the bot's abilities raise major questions for academia. "Claude Code and its ilk are coming for the study of politics like a freight train," he posted on X. Not everyone is so sanguine. The bot lacks the prowess of an excellent software engineer: It sometimes gets stuck on more complicated programming tasks -- and occasionally trips up on simple tasks. As the writer Kelsey Piper has put it, 99 percent of the time, using Claude Code feels like having a tireless magical genius on hand, and 1 percent of the time, it feels like yelling at a puppy for peeing on your couch. Regardless, Claude Code is a win for the AI world. The luster of ChatGPT has worn off, and Silicon Valley has been pumping out slop: Last fall, OpenAI debuted a social network for AI-generated video, which seems destined to pummel the internet with deepfakes, and Elon Musk's Grok recently flooded X with nonconsensual AI-generated porn. But Claude Code feels materially different in the way it presents obvious, immediate real-world utility -- even if it also has the potential to be used to objectionable ends. (Last fall, Anthropic discovered that Chinese state-sponsored hackers had used Claude Code to conduct a sophisticated cyberespionage scheme.) Whatever your feelings on the technology, the bot is evidence that the AI revolution is real. In fact, Claude Code could turn out to be an inflection point for AI progress. A crucial step on the path to artificial general intelligence, or AGI, is thought to be "recursive self-improvement": AI models that can keep making themselves better. So far, this has been largely elusive. Cherny, the Claude Code creator, claims that might be changing. In terms of "recursive self-improvement, we're starting to see early signs of this," he said. "Claude is starting to come up with its own ideas and it's proposing what to build." A year ago, Cherny estimates that Claude Code wrote 10 percent of his code. "Nowadays, it writes 100 percent." Read: Things get strange when AI starts training itself If Claude Code ends up being as powerful as its biggest supporters are promising, it will be equally disruptive. So far, AI has yet to lead to widespread job losses. That could soon change. Annika Lewis, the executive director of a crypto foundation who described herself as "fairly nontechnical," recently used the bot to build a custom tool that scans her fridge and suggests recipes in order to minimize grocery-store runs. Next she wants to hook it up to Instacart so it can order her groceries. In fact, Lewis thinks the bot could help with all kinds of work, she told me. She has two young kids, and had been considering hiring someone to help out with household administrative work such as finding birthday-party venues, registering the kids for extracurricular activities, and booking dental appointments. Now that she has Claude Code, she hopes to automate much of that instead.

[2]

'A new era of software development': Claude Code has Seattle engineers buzzing as AI coding hits new phase

Claude Code has become one of the hottest AI tools in recent months -- and software engineers in Seattle are taking notice. More than 150 techies packed the house at a Claude Code meetup event in Seattle on Thursday evening, eager to trade use cases and share how they're using Anthropic's fast-growing technology. Claude Code is a specialized AI tool that acts like a supercharged pair-programmer for software developers. Interest in Claude Code has surged alongside improvements to Anthropic's underlying models that let Claude handle longer, more complex workflows. "The biggest thing is closing the feedback loop -- it can take actions on its own and look at the results of those actions, and then take the next action," explained Carly Rector, a product engineer at Pioneer Square Labs, the Seattle startup studio that organized Thursday's event at Thinkspace. Software development has emerged as the first profession to be thoroughly reshaped by large language models, as AI systems move beyond answering questions to actively doing the work. Last summer GeekWire reported on a similar event in Seattle focused on Cursor, another AI coding tool that developers described as a major productivity booster. Claude Code is "one of a new generation of AI coding tools that represent a sudden capability leap in AI in the past month or so," wrote Ethan Mollick, a Wharton professor and AI researcher, in a Jan. 7 blog post. Mollick notes that these tools are better at self-correcting their own errors and now have "agentic harness" that helps them work around long-standing AI limitations, including context-window constraints that affect how much information models can remember. On stage at Thursday's event, Rector demoed an app that automatically fixed front-end bugs by having Claude Code control a browser. Johnny Leung, a software engineer at Stripe, said Claude Code has changed how he thinks about being a developer. "It's kind of evolving the mentality from just writing code to becoming like an architect, almost like a product manager," he said on stage during his demo. R. Conner Howell, a software engineer in Seattle, showed how Claude Code can act as a personal cycling coach, querying performance data from databases and generating custom training plans -- an example of the tool's impact extending beyond traditional software development. Earlier this week Anthropic -- which is reportedly raising another $10 billion at a $350 billion valuation -- released Claude Cowork, essentially Claude Code's non-developer cousin that is built for everyday knowledge work instead of just programming. AI coding tools are energizing longtime software developers like Damon Cortesi, who co-founded Seattle startup Simply Measured in 2010 and is now an engineer at Airbnb. He said Thursday's event was the first tech meetup he's attended in more than five years. "There's no limit to what I can think about and put out there and actually make real," he said. In a post titled "How Claude Reset the AI Race," New York Magazine columnist John Herrman noted the growing concern around coding automation and job displacement. "If you work in software development, the future feels incredibly uncertain," he wrote. Anthropic, which opened an office in Seattle in 2024, said it used Claude Code to build Claude Cowork itself. However, analysts at Baird issued a report this week expressing skepticism that other businesses will simply start building their own software with these new AI tools. "Vibe coding and AI code generation certainly make it easier to build software, but the technical barriers to coding have not been the drivers of software moats for some time," they wrote. "For the most successful and scaled software companies, determining what to build next and how it should function within a broader system is fundamentally more important and more challenging than the technical act of building and coding it." For now, Claude Code is being rapidly adopted. The tool reached a $1 billion run rate six months after launch in May. OpenAI's Codex and Google's Antigravity offer similar capabilities. "We're excited to see all the cool things you do with Claude Code," Caleb John, a young Seattle entrepreneur working at Pioneer Square Labs, told the crowd. "It's really a new era of software development."

[3]

Behind the Curtain: The AI future has arrived

In eight hours, Jim built four apps on his phone -- all fully functioning, all beautifully designed and intuitive. "My mind is officially blown in a way it never has been before," he texted Mike on Thursday. * We've been building products and companies for 20 years. Any of those apps would have taken multiple people and many weeks to hit this level of design and usability. * Jim wanted to create a test to screen for people who'll excel at using AI. He built a 30-question quiz on his phone in two hours, then easily added five-minute training courses for each skill set. Claude shows in vivid and unforgettable ways how easily AI will perform complex human tasks instantly -- and forever change work, jobs and chores. Google, OpenAI, xAI and other competitors are racing to match and exceed Claude. * You can assume there'll be leapfrogging advancements in this hyper-competitive race. * Yes, these AI tools remain imperfect. But when you experiment with them, you'll see they're advancing lightning-fast. The big picture: 2026 seems increasingly likely to be the year AI will go from fascinating aspiration to actual widespread application. * Chris Lehane, OpenAI's chief global affairs officer, tells us: "The whole waterline in capabilities has risen -- everyone who has a boat, whether a big boat or a smaller boat, is rising on this rising tide. The capabilities are moving faster, and we as a society need to move faster if we want as many people as possible to have a fair chance of getting their fair piece of the intelligence age." Inside Jim's test run: I used Claude Opus 4.5, Anthropic's flagship AI, accessed through a $20/month Claude Pro subscription. How it works: This version can actually build things -- not just chat. It writes code, creates working apps, and delivers downloadable files, all from my phone. You talk to it conversationally, directing what you want and how it should work. * And I'm a tech dope who knows nothing about coding. I thought Ruby on Rails, a popular tool for developers, was some kind of LSD. And ColdFusion, a web development platform, sounds like the science explaining why my beer freezes at Lambeau Field. What's crazier: I've hardly touched my souped-up, $100-per-month desktop version. Claude's Cowork is an agent that can take on complex, multistep tasks and execute them on your behalf. Point it at a folder, describe what you want, and walk away. It's macOS-only for now. Case in point: To create my quiz to gauge someone's AI agility, I started with a thesis about who's likely to excel in our new world -- then fed it into ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude to stress-test and perfect. * All three LLMs offered different but related feedback, and helped me distill AI adeptness into five traits, in this order: Interrogative Curiosity, Taste, Contextual Wisdom, Architectural Discipline and Iterative Stamina. Next, I used all three to help create a 30-question survey modeled after Gallup's StrengthsFinder and other personality tests for professional success. * Then I used Claude's Opus 4.5 to build an interactive test, scoring system, and results page. The design and user experience are astonishingly good. * Finally, I had Claude build five-minute training sessions to help users improve in their areas of weakness. I shared the final program, AGI-Q (above), with a dozen friends, who all marveled at its ease. I'll make the app public once I get more comfortable with the test itself and the results' validity. (If you're super-eager to see it, shoot your text number to [email protected] and I'll send a private version.) The bottom line: Plenty of these tools are free -- use them voraciously, and get comfortable and adept. Your career likely depends on it.

[4]

How Claude Reset the AI Race

Over the holidays, some strange signals started emanating from the pulsating, energetic blob of X users who set the agenda in AI. OpenAI co-founder Andrej Karpathy, who coined the term "vibe coding," but had recently minimized AI programming as helpful but unremarkable "slop," was suddenly talking about how he'd "never felt this much behind as a programmer," and tweeting in wonder about feeling like he was using a "powerful alien tool." Others users traded it's so overs and we're so backs, wondering aloud if software engineering had just been "solved" or was "done," as recently anticipated by some industry leaders. An engineer at Google wrote of a competitor's tool, "I'm not joking and this isn't funny," describing how it replicated a year of her team's work "in an hour." She was talking about Claude Code. Everyone was. The broad adoption of AI tools has been strange and unevenly distributed. As general-purpose search, advice, and text-generation tools, they're in wide use. Across many workplaces, managers and employees alike have struggled a bit more to figure out how to deploy them productively, or to align their interests (we can reasonably speculate that in many sectors, employees are getting more productivity out of unsanctioned, gray-area AI use than they are through their workplace's official tools). The clearest exception to this, however, is programming. In 2023, it was already clear that LLMs had the potential to dramatically change how software gets made, and coding assistance tools were some of the first tools companies found reason to pay for. In 2026, the AI-assisted future of programming is rapidly coming into view. The practice of writing code, as Karpathy puts it, has moved up to another "layer of abstraction," where a great deal of old tasks can be managed in plain English, and writing software with the help of AI tools amounts to mastering "agents, subagents, their prompts, contexts, memory, modes, permissions, tools, plugins, skills, hooks, MCP, LSP, slash commands, workflows, [and] IDE integrations" -- which is a long way of saying that, soon, it might not involve actually writing much code at all. What happened? Some users speculated that the winter break just gave people some time to absorb how far things had come. Really, as professor and AI analyst Ethan Mollick puts it, Anthropic, the company behind Claude, had stitched together a "wide variety of tricks" that helped tip the product into a more general sort of usefulness than had been possible before: to deal with the limited "memory" of LLMs, it started generating and working from "compacted" summaries of what it had been doing so far, allowing it to work for longer; it was better able to call on established "skills" and specialized "subagents" that it could follow or delegate to smaller, divvied-up tasks; it was better at interfacing with other services and tools, in part because the tech industry has started formalizing how such tools can talk to one another. The end result is a product that can, from one prompt or hundreds, generate code -- and complete websites, features, or apps -- to a degree that's taken even those in the AI industry by surprise. (To be clear, this isn't all about Claude, although it's the clear exemplar and favorite among developers: Similar tools from OpenAI and Google also took steps forward at the end of last year, which helped feed AI Twitter's various explosions of mania, doom, and elation.) If you work in software development, the future feels incredibly uncertain. Tools like Claude Code are plainly automating a lot of tasks that programmers had to do manually until quite recently, allowing non-experts to write software and established programmers to increase their output dramatically. Optimists in the industry are arguing that the sector is about to experience the Jevons Paradox, a phenomenon in which a dramatic reduction in cost of using a resource (in the classic formulation, coal use; this time around, software production) can lead to far greater demand for the resource. Against the backdrop of years of tech industry layoffs, and CEOs signaling to shareholders that they expect AI to provide lots of new efficiencies, plenty of others are understandably slipping into despair. The consequences of how code gets written won't just be contained to the tech industry, of course -- there aren't many jobs left in the American economy that aren't influenced in some way by software -- and some Claude Code users pointed out that the tool's capabilities, which were designed by and for people who are comfortable coding, might be able to generalize. In a basic sense, what it had gotten better at was working on tasks over a longer period, calling on existing tools, and producing new tools when necessary. As the programmer and AI critic Simon Willison put it, Claude Code at times felt more like a "general agent" than a developer tool, which could be deployed toward "any computer task that can be achieved by executing code or running terminal commands," which covers, well, "almost anything, provided you know what you're doing with it." Anthropic seems to agree, and within a couple of weeks of Claude Code's breakout, announced a preview of a tool called Cowork: Willison tested the tool on a few tasks -- check a folder on his computer for unfinished drafts, check his website to make sure he hadn't published them, and recommend which is closest to being done -- and came away impressed with both its output and the way it was able to navigate his computer to figure out what he was talking about. "Security worries aside, Cowork represents something really interesting," he wrote. "This is a general agent that looks well-positioned to bring the wildly powerful capabilities of Claude Code to a wider audience." These tools represent both a realization of long-promised "agentic" AI tools and a clear break with how they'd been developing up until recently. Early ads for enterprise AI software from companies like Microsoft and Google suggested, often falsely, that their tools could simply take work off users' plates, dealing with complex commands independently and pulling together all the data and tools necessary to do so. Later, general-purpose tools from companies like OpenAI and Anthropic, now explicitly branded as agents, suggested that they might be able to work on your behalf by taking control of your computer interface, reading your browser, and clicking around on your behalf. In both cases, the tools overpromised and underdelivered, overloading LLMs with too much data to productively parse and deploying them in situations where they were set up to fail. Cowork charts a different path to a similar goal, and one that runs through code. In Willison's example, Cowork's agent didn't just direct its attention to a folder, drift back to the web, and start churning out text. It wrote and executed a command in the Mac terminal, hooked into a web search tool, and coded a bespoke website with "animated encouragements" for Willison to finish his posts. In carrying out a task, in other words, it did something that LLM-based tools have been doing much more in the past year: Rather than attempting to carry the task out directly, they first see if they might be able to write a quick script, or piece of software, that can accomplish the goal instead. The ability to rapidly spit out functional pieces of software has major (if not exactly clear) implications for the people and companies who make software. It also suggests an interesting path for AI adoption for lots of other industries, too. AI firms are betting that next generation of AI tools will try to get work done not just by throwing your problems into their context windows and seeing what comes out the other side, but by architecting and coding more conventional pieces of software, on the fly, that might be able handle the work better. The question of whether LLMs are well-suited to the vast range of tasks that make up modern knowledge work is still important, in other words, but perhaps not as urgent as the question of what the economy might do with a near-infinite supply of custom software produced by people who don't know how to code.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Anthropic's Claude Code is transforming how software gets made, allowing users with no programming experience to build fully functional apps in hours. The AI coding tool reached a $1 billion run rate within six months and has tech industry professionals questioning the future of traditional software development as advanced AI capabilities automate tasks that once required teams of developers and weeks of work.

AI Coding Tools Enter a New Era of Software Development

Over the winter holidays, something shifted in the tech industry. While most people celebrated with family, developers and entrepreneurs were experimenting with Claude Code, Anthropic's AI coding tool that's generating buzz not seen since ChatGPT's debut

1

. Alex Lieberman, co-founder of Morning Brew, created "iMessage Wrapped"—a web app analyzing nearly 1 million text messages—without writing a single line of code1

. The application represents a fundamental shift in how software development works, as AI agents capable of automating complex workflows move from promise to reality.

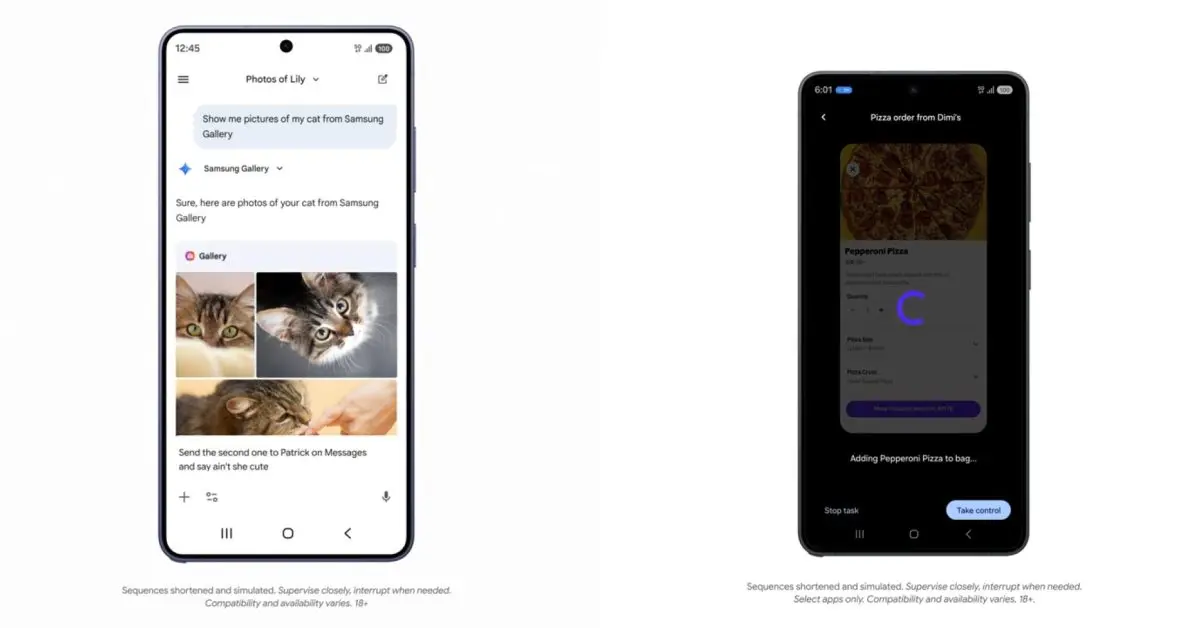

Source: NYMag

The tool's capabilities extend far beyond traditional coding. Users have deployed Claude Code to create custom MRI viewers, analyze DNA data, manage personal finances, and even monitor plant growth by tracking soil moisture and leaf temperature

1

. One journalist built four fully functioning apps on his phone in eight hours, tasks that would have previously required multiple people and many weeks to complete3

. "My mind is officially blown in a way it never has been before," he reported after the experience3

.Advanced AI Capabilities Drive Unprecedented Adoption

Claude Code reached a $1 billion run rate just six months after its May launch, signaling rapid market acceptance

2

. More than 150 software engineers packed a Seattle meetup in January to share use cases and discuss how they're integrating the technology into their workflows2

. The enthusiasm stems from what Wharton professor Ethan Mollick calls "a sudden capability leap" that occurred in recent months2

.

Source: GeekWire

What distinguishes Claude Code from earlier AI programming tools is its ability to close the feedback loop. "It can take actions on its own and look at the results of those actions, and then take the next action," explained Carly Rector, a product engineer at Pioneer Square Labs

2

. The system generates compacted summaries to overcome LLMs' limited memory, allowing it to work on longer, more complex tasks4

. It can call on specialized subagents and established skills, delegating smaller tasks while maintaining context across extended workflows4

.Developers Rethink Their Role as AI Handles Traditional Tasks

The impact on programmers has been profound. OpenAI co-founder Andrej Karpathy, who coined the term "vibe coding," admitted he'd "never felt this much behind as a programmer" while describing the tool as feeling like a "powerful alien tool"

4

. A Google engineer reported that Claude Code replicated a year of her team's work in just an hour4

. Johnny Leung, a software engineer at Stripe, noted that the technology is "evolving the mentality from just writing code to becoming like an architect, almost like a product manager"2

.

Source: The Atlantic

Stanford political scientist Andrew Hall used Claude Code to analyze raw data from an old research paper on mail-in voting. In roughly an hour, the bot replicated his findings and produced a complete research paper with charts and literature review, making only minor errors that a human might make . Sara Du, founder of AI start-up Ando, uses it to manage texts with real-estate agents, asking it to compile tables of Zillow listings from her iMessages

1

.App Creation Becomes Accessible to Non-Technical Users

While Anthropic initially positioned Claude Code as a tool for developers, its adoption has spread to product managers, salespeople, and designers—a development that "was hugely surprising" to Boris Cherny, the Anthropic employee who created the tool

1

. The cheapest version costs $20 per month, and Anthropic has since released Claude Cowork, a research preview designed specifically for non-developers to handle everyday knowledge work1

2

.One user created an AI agility assessment tool called AGI-Q in just two hours on his phone, complete with a 30-question quiz, scoring system, results page, and five-minute training courses for each skill set

3

. The design and user experience were "astonishingly good" according to the creator, who has been building products for 20 years3

. This represents a dramatic reduction in the barriers to software creation, making developer productivity tools accessible to those without traditional programming backgrounds.Related Stories

Job Automation Concerns Rise as AI Race Intensifies

The rapid advancement of AI coding tools has sparked anxiety about job displacement in the tech industry. "If you work in software development, the future feels incredibly uncertain," wrote New York Magazine columnist John Herrman

4

. Tools like Claude Code are automating tasks that programmers handled manually until recently, allowing non-experts to write software and established developers to increase output dramatically4

.Yet some analysts remain skeptical about the broader implications. Baird analysts noted that "vibe coding and AI code generation certainly make it easier to build software, but the technical barriers to coding have not been the drivers of software moats for some time"

2

. They argue that determining what to build and how it functions within broader systems remains more important than the technical act of coding itself2

.Optimists suggest the industry might experience a Jevons Paradox, where dramatically reduced costs of software production lead to far greater demand, potentially creating new opportunities

4

. Chris Lehane, OpenAI's chief global affairs officer, describes the moment as a rising tide: "The whole waterline in capabilities has risen—everyone who has a boat, whether a big boat or a smaller boat, is rising on this rising tide"3

.Competition Heats Up as OpenAI and Google Respond

Anthropic, which reportedly is raising another $10 billion at a $350 billion valuation, used Claude Code to build Claude Cowork itself, demonstrating the tool's capacity for complex, real-world applications

2

. The company opened a Seattle office in 2024 as it expands its presence in key tech hubs2

.OpenAI's Codex and Google's Antigravity offer similar capabilities, with all three companies making significant advances at the end of 2025

2

4

. The competitive AI race has accelerated as companies leapfrog each other's advancements3

. While these AI tools remain imperfect, they're advancing at lightning speed3

.Damon Cortesi, who co-founded Seattle startup Simply Measured in 2010 and now works as an engineer at Airbnb, attended his first tech meetup in more than five years to learn about Claude Code. "There's no limit to what I can think about and put out there and actually make real," he said

2

. As 2026 unfolds, AI appears poised to transition from fascinating aspiration to widespread application across the tech industry and beyond3

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[2]

[4]

Related Stories

Anthropic partners with CodePath to train next generation of coders using Claude Code

13 Feb 2026•Technology

Anthropic's Claude Code Goes Web-Based: A Game-Changer for AI-Assisted Coding

20 Oct 2025•Technology

AI agents transform software development but expose critical need for human oversight

21 Feb 2026•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with Defense Production Act over AI military use restrictions

Policy and Regulation

2

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

3

Anthropic accuses Chinese AI labs of stealing Claude through 24,000 fake accounts

Policy and Regulation