Consciousness May Require Physical Brain Computation, Not Just Abstract Code

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Why consciousness can't be reduced to code

Today's arguments about consciousness often get stuck between two firm camps. One is computational functionalism, which says thinking can be fully described as abstract information processing. If a system has the right functional organization (regardless of the material it runs on), it should produce consciousness. The other is biological naturalism, which argues the opposite. It says consciousness cannot be separated from the special features of living brains and bodies because biology is not just a container for cognition, it is part of cognition itself. Both views capture real insights, but the deadlock suggests an important piece is still missing. In our new paper, we propose a different approach: biological computationalism. The label is meant to be provocative, but also to sharpen the conversation. Our main argument is that the standard computational framework is broken, or at least poorly suited to how brains actually work. For a long time, it has been tempting to picture the mind as software running on neural hardware, with the brain "computing" in roughly the way a conventional computer does. But real brains are not von Neumann machines, and forcing that comparison leads to shaky metaphors and fragile explanations. If we want a serious account of how brains compute, and what it would take to build minds in other substrates, we first need a broader definition of what "computation" can be. Biological computation, as we describe it, has three core features. Hybrid Brain Computation in Real Time First, biological computation is hybrid. It mixes discrete events with continuous dynamics. Neurons fire spikes, synapses release neurotransmitters, and networks shift through event-like states. At the same time, these events unfold within constantly changing physical conditions such as voltage fields, chemical gradients, ionic diffusion, and time-varying conductances. The brain is not purely digital, and it is not simply an analog machine either. Instead, it works as a multi-layered system where continuous processes influence discrete events, and discrete events reshape the continuous background, over and over, in an ongoing feedback loop. Why Brain Computation Cannot Be Separated by Scale Second, biological computation is scale-inseparable. In conventional computing, it is often possible to cleanly separate software from hardware, or a "functional level" from an "implementation level." In the brain, that kind of separation breaks down. There is no neat dividing line where you can point to the algorithm on one side and the physical mechanism on the other. Cause and effect run across many scales at once, from ion channels to dendrites to circuits to whole-brain dynamics, and these levels do not behave like independent modules stacked in layers. In biological systems, changing the "implementation" changes the "computation," because the two are tightly intertwined. Metabolism and Energy Constraints Shape Intelligence Third, biological computation is metabolically grounded. The brain operates under strict energy limits, and those limits shape its structure and function everywhere. This is not just an engineering detail. Energy constraints influence what the brain can represent, how it learns, which patterns remain stable, and how information is coordinated and routed. From this perspective, the tight coupling across levels is not accidental complexity. It is an energy optimization strategy that supports robust, flexible intelligence under severe metabolic limits. The Algorithm Is the Substrate Taken together, these three features point to a conclusion that can feel strange if you are used to classical computing ideas. Computation in the brain is not abstract symbol manipulation. It is not simply about moving representations around according to formal rules while the physical medium is treated as "mere implementation." In biological computation, the algorithm is the substrate. The physical organization does not just enable the computation, it is what the computation consists of. Brains do not merely run a program. They are a specific kind of physical process that computes by unfolding through time. What This Means for AI and Synthetic Minds This view also exposes a limitation in how people often describe modern AI. Even powerful systems mostly simulate functions. They learn mappings from inputs to outputs, sometimes with impressive generalization, but the computation is still a digital procedure running on hardware built for a very different style of computing. Brains, by contrast, carry out computation in physical time. Continuous fields, ion flows, dendritic integration, local oscillatory coupling, and emergent electromagnetic interactions are not just biological "details" that can be ignored while extracting an abstract algorithm. In our view, these are the computational primitives of the system. They are the mechanisms that enable real-time integration, resilience, and adaptive control. Not Biology Only, But Biology Like Computation This does not mean we think consciousness is somehow restricted to carbon-based life. We are not arguing "biology or nothing." Our claim is narrower and more practical. If consciousness (or mind-like cognition) depends on this kind of computation, then it may require biological-style computational organization, even if it is built in new substrates. The key issue is not whether the substrate is literally biological, but whether the system instantiates the right kind of hybrid, scale-inseparable, metabolically (or more generally energetically) grounded computation. A Different Target for Building Conscious Machines That reframes the goal for anyone trying to build synthetic minds. If brain computation cannot be separated from how it is physically realized, then scaling digital AI alone may not be enough. This is not because digital systems cannot become more capable, but because capability is only part of the puzzle. The deeper risk is that we may be optimizing the wrong thing by improving algorithms while leaving the underlying computational ontology unchanged. Biological computationalism suggests that building truly mind-like systems may require new kinds of physical machines whose computation is not organized as software on hardware, but spread across levels, dynamically linked, and shaped by the constraints of real-time physics and energy. So if we want something like synthetic consciousness, the central question may not be, "What algorithm should we run?" It may be, "What kind of physical system must exist for that algorithm to be inseparable from its own dynamics?" What features are required, including hybrid event-field interactions, multi-scale coupling without clean interfaces, and energetic constraints that shape inference and learning, so that computation is not an abstract description layered on top but an intrinsic property of the system itself? That is the shift biological computationalism calls for. It moves the challenge from finding the right program to finding the right kind of computing matter.

[2]

Consciousness May Require a New Kind of Computation - Neuroscience News

Summary: A new theoretical framework argues that the long-standing split between computational functionalism and biological naturalism misses how real brains actually compute. The authors propose "biological computationalism," the idea that neural computation is inseparable from the brain's physical, hybrid, and energy-constrained dynamics rather than an abstract algorithm running on hardware. In this view, discrete neural events and continuous physical processes form a tightly coupled system that cannot be reduced to symbolic information processing. The theory suggests that digital AI, despite its capabilities, may not recreate the essential computational style that gives rise to conscious experience. Instead, truly mind-like cognition may require building systems whose computation emerges from physical dynamics similar to those found in biological brains. Right now, the debate about consciousness often feels frozen between two entrenched positions. On one side sits computational functionalism, which treats cognition as something you can fully explain in terms of abstract information processing: get the right functional organization (regardless of the material it runs on) and you get consciousness. On the other side is biological naturalism, which insists that consciousness is inseparable from the distinctive properties of living brains and bodies: biology isn't just a vehicle for cognition, it is part of what cognition is. Each camp captures something important, but the stalemate suggests that something is missing from the picture. In our new paper, we argue for a third path: biological computationalism. The idea is deliberately provocative but, we think, clarifying. Our core claim is that the traditional computational paradigm is broken or at least badly mismatched to how real brains operate. For decades, it has been tempting to assume that brains "compute" in roughly the same way conventional computers do: as if cognition were essentially software, running atop neural hardware. But brains do not resemble von Neumann machines, and treating them as though they do forces us into awkward metaphors and brittle explanations. If we want a serious theory of how brains compute and what it would take to build minds in other substrates, we need to widen what we mean by "computation" in the first place. Biological computation, as we describe it, has three defining properties. First, it is hybrid: it combines discrete events with continuous dynamics. Neurons spike, synapses release neurotransmitters, and networks exhibit event-like transitions, yet all of this is embedded in evolving fields of voltage, chemical gradients, ionic diffusion, and time-varying conductances. The brain is not purely digital, and it is not merely an analog machine either. It is a layered system where continuous processes shape discrete happenings, and discrete happenings reshape continuous landscapes, in a constant feedback loop. Second, it is scale-inseparable. In conventional computing, we can draw a clean line between software and hardware, or between a "functional level" and an "implementation level." In brains, that separation is not clean at all. There is no tidy boundary where we can say: here is the algorithm, and over there is the physical stuff that happens to realize it. The causal story runs through multiple scales at once, from ion channels to dendrites to circuits to whole-brain dynamics and the levels do not behave like modular layers in a stack. Changing the "implementation" changes the "computation," because in biological systems, those are deeply entangled. Third, biological computation is metabolically grounded. The brain is an energy-limited organ, and its organization reflects that constraint everywhere. Importantly, this is not just an engineering footnote; it shapes what the brain can represent, how it learns, which dynamics are stable, and how information flows are orchestrated. In this view, tight coupling across levels is not accidental complexity. It is an energy optimization strategy: a way to produce robust, adaptive intelligence under severe metabolic limits. These three properties lead to a conclusion that can feel uncomfortable if we are used to thinking in classical computational terms: computation in the brain is not abstract symbol manipulation. It is not simply a matter of shuffling representations according to formal rules, with the physical medium relegated to "mere implementation." Instead, in biological computation, the algorithm is the substrate. The physical organization does not just support the computation; it constitutes it. Brains don't merely run a program. They are a particular kind of physical process that performs computation by unfolding in time. This also highlights a key limitation in how we often talk about contemporary AI. Current systems, for all their power, largely simulate functions. They approximate mappings from inputs to outputs, often with impressive generalization, but the computation is still fundamentally a digital procedure executed on hardware designed for a very different computational style. Brains, by contrast, instantiate computation in physical time. Continuous fields, ion flows, dendritic integration, local oscillatory coupling, and emergent electromagnetic interactions are not just biological "details" we might safely ignore while extracting an abstract algorithm. In our view, these are the computational primitives of the system. They are the mechanism by which the brain achieves real-time integration, resilience, and adaptive control. This does not mean we think consciousness is magically exclusive to carbon-based life. We are not making a "biology or nothing" argument. What we are claiming is more specific: if consciousness (or mind-like cognition) depends on this kind of computation, then it may require biological-style computational organization, even if it is implemented in new substrates. In other words, the crucial question is not whether the substrate is literally biological, but whether the system instantiates the right class of hybrid, scale-inseparable, metabolically (or more generally energetically) grounded computation. That shift changes the target for anyone interested in synthetic minds. If the brain's computation is inseparable from the way it is physically realized, then scaling digital AI alone may not be sufficient. Not because digital systems can't become more capable, but because capability is only part of the story. The deeper challenge is that we might be optimizing the wrong thing: improving algorithms while leaving the underlying computational ontology untouched. Biological computationalism suggests that to engineer genuinely mind-like systems, we may need to build new kinds of physical systems: machines whose computing is not layered neatly into software on hardware, but distributed across levels, dynamically coupled, and grounded in the constraints of real-time physics and energy. So, if we want something like synthetic consciousness, the problem may not be, "What algorithm should we run?" The problem may be, "What kind of physical system must exist for that algorithm to be inseparable from its own dynamics?" What are the necessary features -- hybrid event-field interactions, multi-scale coupling without clean interfaces, energetic constraints that shape inference and learning -- such that computation is not an abstract description laid on top, but an intrinsic property of the system itself? That is the shift biological computationalism demands: moving from a search for the right program to a search for the right kind of computing matter. On biological and artificial consciousness: A case for biological computationalism The rapid advances in the capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) have galvanised public and scientific debates over whether artificial systems might one day be conscious. Prevailing optimism is often grounded in computational functionalism: the assumption that consciousness is determined solely by the right pattern of information processing, independent of the physical substrate. Opposing this, biological naturalism insists that conscious experience is fundamentally dependent on the concrete physical processes of living systems. Despite the centrality of these positions to the artificial consciousness debate, there is currently no coherent framework that explains how biological computation differs from digital computation, and why this difference might matter for consciousness. Here, we argue that the absence of consciousness in artificial systems is not merely due to missing functional organisation but reflects a deeper divide between digital and biological modes of computation and the dynamico-structural dependencies of living organisms. Specifically, we propose that biological systems support conscious processing because they (i) instantiate scale-inseparable, substrate-dependent multiscale processing as a metabolic optimisation strategy, and (ii) alongside discrete computations, they perform continuous-valued computations due to the very nature of the fluidic substrate from which they are composed. These features - scale inseparability and hybrid computations - are not peripheral, but essential to the brain's mode of computation. In light of these differences, we outline the foundational principles of a biological theory of computation and explain why current artificial intelligence systems are unlikely to replicate conscious processing as it arises in biology.

Share

Share

Copy Link

A new theoretical framework proposes biological computationalism as a third path between computational functionalism and biological naturalism. Researchers argue that consciousness cannot be reduced to abstract information processing because brain computation is inseparable from its physical, hybrid, and energy-constrained dynamics. This challenges assumptions about whether digital AI can truly recreate conscious experience.

Consciousness Debate Gets a Third Path

The long-standing debate about consciousness has been trapped between two opposing views. Traditional computational functionalism claims that thinking can be fully described as abstract information processing, where the right functional organization produces consciousness regardless of the material running it

1

. On the other side, biological naturalism insists consciousness cannot be separated from living brains and bodies because biology is not just a container for cognition, it is cognition itself2

. Both capture important insights, but the stalemate suggests something crucial is missing.A new theoretical framework offers a third approach called biological computationalism

1

. The core argument challenges the standard computational framework that has dominated thinking about minds for decades. Brains do not work like von Neumann machines, and forcing that comparison creates fragile explanations about how cognition actually operates2

.

Source: Neuroscience News

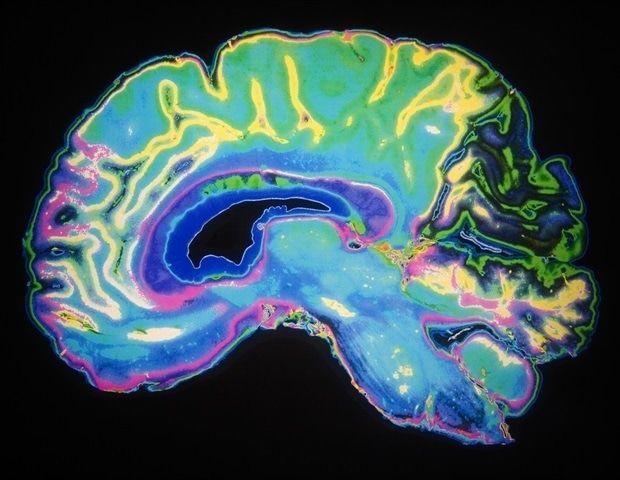

Brain Computation Works Through Hybrid Scale-Inseparable Dynamics

Biological computationalism rests on three defining features that distinguish real brain computation from conventional computing. First, it operates as hybrid computation that mixes discrete events with continuous dynamics

1

. Neurons fire spikes, synapses release neurotransmitters, and networks shift through event-like states. Simultaneously, these events unfold within constantly changing physical conditions including voltage fields, chemical gradients, ionic diffusion, and time-varying conductances2

. The brain is neither purely digital nor simply analog, but a multi-layered system where continuous processes influence discrete events, and discrete events reshape the continuous background in an ongoing feedback loop.Second, neural computation is scale-inseparable

1

. Conventional computing allows a clean software-hardware split between functional and implementation levels. In brains, that separation breaks down completely. There is no neat dividing line where the algorithm sits on one side and the physical mechanism on the other2

. Cause and effect run across many scales at once, from ion channels to dendrites to circuits to whole-brain dynamics, and these levels do not behave like independent modules stacked in layers. Changing the implementation changes the computation because the two are tightly intertwined.Metabolism Shapes Intelligence Through Energy-Constrained Dynamics

The third feature reveals that brain computation is metabolically grounded

1

. The brain operates under strict energy limits that shape its structure and function everywhere. These energy-constrained dynamics are not just engineering details but influence what the brain can represent, how it learns, which patterns remain stable, and how information is coordinated and routed2

. The tight coupling across levels functions as an energy optimization strategy that supports robust, flexible intelligence under severe metabolic limits.Related Stories

Physical Substrate Constitutes the Computation

These three properties lead to a conclusion that challenges classical computing ideas: the algorithm is the substrate

1

. Computation in the brain is not abstract symbol manipulation or moving representations around according to formal rules while treating the physical medium as mere implementation. The physical organization does not just enable the computation, it is what the computation consists of2

. Brains do not merely run a program but are a specific kind of physical process that computes by unfolding through time.This perspective exposes limitations in how current AI systems operate. Even powerful systems mostly simulate functions, learning mappings from inputs to outputs with impressive generalization, but the computation remains a digital procedure running on hardware built for a different style of computing

1

. Brains carry out computation in physical time, where continuous fields, ion flows, dendritic integration, local oscillatory coupling, and emergent electromagnetic interactions serve as the computational primitives of the system.What This Means for Conscious Experience and AI

The framework suggests that digital AI, despite its capabilities, may not recreate the essential computational style that gives rise to conscious experience

2

. Current functionalism approaches treat cognition as software running atop neural hardware, but this metaphor fails to capture how event-field interactions and metabolism fundamentally shape information processing in biological systems.Truly mind-like cognition may require building systems whose computation emerges from physical dynamics similar to those found in biological brains

2

. This raises questions about whether consciousness can exist in purely digital substrates or whether it demands the kind of hybrid, scale-inseparable, energy-grounded computation that characterizes living neural tissue. For AI researchers and neuroscientists, this means watching whether future systems can incorporate these biological computational principles, and whether doing so changes what kinds of cognition become possible in artificial systems.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[2]

Related Stories

The Quest for Conscious AI: Algorithms, Challenges, and Philosophical Debates

27 Oct 2025•Science and Research

The Limitations of AI Art: A Reflection on Human Creativity and Consciousness

09 Feb 2025•Technology

Brain Cells Outperform AI in Learning Speed and Efficiency, Study Reveals

13 Aug 2025•Science and Research

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic sues Pentagon over supply chain risk label after refusing autonomous weapons use

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round as questions swirl around AI bubble and profitability

Business and Economy