Google Gemini beats ChatGPT by turning AI into a default, not a destination

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Google's Gemini is beating OpenAI's ChatGPT in the AI chatbot race

A year ago, the AI race looked like a popularity contest. The scoreboard lived in screenshots: Who had the slickest demo, the snappiest answers, the most viral prompt. Then, the grown-up version of AI arrived, and the prize turned out to be the same thing it has always been on the internet: default behavior. The place people already start. The box they already type into. And on that battlefield, Google $GOOGL doesn't need a miracle. Google just needs to keep acting like Google. ChatGPT has a brand problem most companies would kill for: It's famous. Fame is great for growth. But fame also paints a target on your forehead and is a lightning rod for every mistake. OpenAI made AI feel like a place you can go, and its chatbot, ChatGPT, made a new behavior mainstream fast. People just needed curiosity, a blank box, a blinking cursor, and one decent answer that felt like magic. Google, though, doesn't need magic. Google needs repetition. Google can ship AI at the speed of its own update cycle -- Search, Android, Chrome, Gmail, Maps, Workspace, Calendar, YouTube -- and make "using Gemini" feel like "using the internet." Google has spent two decades turning repetition into a business model, and it's trying to do it again with AI -- by turning Gemini from a destination into a default, and making "ask the machine" feel like something you do without thinking about where you're doing it -- the way it did with search, ads, and the browser tab you keep open like it's providing emotional support. Google has been building its AI as a place you end up because the rest of the internet keeps funneling you right there. A challenger can build a better destination and still spend years fighting the fact that most people already live inside Google's primary-colored world -- and that most people are busy and most people are lazy. "Good enough" can spread faster than "best" in the right circumstances. Alphabet reports fourth-quarter and full-year 2025 results on Wednesday. The numbers will matter, the spending will matter, the guidance will matter. But beneath all that, the earnings call is also a checkpoint in a broader fight that has shifted from "who has the best chatbot" to "which chatbot actually gets installed." OpenAI still has the most famous destination in the category. But Google is building the default layer that the entire category runs on. ChatGPT won the destination. Google is trying to win the default -- and defaults have a way of becoming history. The internet already routes through Google-shaped doorways. According to StatCounter, in January, Google held 89.8% of the global search engine market share. Chrome accounts for 71.4% of global browser use. Android powered 70.4% of the global mobile operating system market. Those numbers show who gets to turn a new behavior into a reflex without asking anyone to change their routine. A destination wins when people make a deliberate trip. A default wins when people don't. OpenAI did the hard part first: It made people want the trip. Google wants to make the trip unnecessary. If the "ask the machine" moment happens inside the place you already start, the chatbot stops being something you seek out and becomes a behavior you perform. The "AI war" isn't a single battle. It's a stack of habits. People don't wake up thinking, Today I'll adopt an AI assistant. They wake up and do what they already do: search, scroll, browse, tap a home screen, open a document, refresh a tab. Google owns more of those motions than any company alive, and it's been quietly threading its models into the motions themselves. Last fall, Google began integrating Gemini directly into Chrome, including features meant to help synthesize content and answer questions within browsing, and Google has been pushing toward more "agentic" browsing tools. If you're OpenAI, that's the nightmare scenario: The most common starting point on the internet quietly grows a second brain. Google's entire business history is a case study in what happens when the default is everywhere and good enough -- good enough to keep people inside the flow, good enough to keep advertisers paying for intent. The AI layer lets Google do the same trick again, this time with cognition. Instead of sending you out onto the vast worldwide web and hoping you come back, the AI assistant can live alongside your browsing session, your search session, your work session, your life session. In CEO Sundar Pichai's prepared remarks on Alphabet's Q3 2025 earnings call, he framed the company's "full-stack" approach as infrastructure, models, and products that "bring AI to people everywhere," then pointed straight at Chrome, saying the company was "reimagin[ing] Chrome as a browser powered by AI through deep integrations with Gemini and AI Mode in Search." The operative word there? "Deep." People don't choose a deep integration. They encounter it. Apple $AAPL recently announced a multiyear partnership to integrate Google's Gemini models into a revamped Siri later in 2026 -- a perfect example because Siri is a distribution channel masquerading as a personality. If a company with Apple's aesthetic and Apple's control decides to borrow Google's brain for the interface it uses to sit in your pocket, that sure looks like the market voting for Google as a foundation layer. If Apple is a kingmaker, it just handed out a crown. On Tuesday, Google Cloud and Liberty Global agreed to a five-year partnership to integrate Gemini across Liberty Global's European footprint, including 80 million fixed and mobile connections. And Samsung's co-CEO said the company expects to double the number of mobile devices with "Galaxy AI" features to 800 million units in 2026, with those features largely powered by Gemini. That's a factory output number. OpenAI created a destination. Google has the leverage to make the category ambient -- a layer that follows people everywhere they go. If this fight ends with AI becoming a standard interface for information and action, the company that controls the interface surfaces gets to set the tolls. And Google has spent 25 years perfecting tolls. For a while, that's where the story tilted toward OpenAI. ChatGPT felt like the place you went when you wanted the best answer. Google felt like the place you went because your finger already knew where the box was. That gap made it possible to imagine a future where the destination won, even if it had to fight for every click. But the quality narrative around Gemini has stopped sounding like internal morale and started sounding like external consensus, including on public leaderboards that aren't run by Google. On LMArena's Text Arena leaderboard -- a large, continual set of head-to-head user preference matchups -- gemini-3-pro is ranked No. 1 as of Jan. 29, 2026, with more than 5.1 million total votes across models. That's a real-time signal that the "Google can't ship a great model" stereotype is becoming outdated, at least for many users in many everyday interactions. The behavioral economics of AI are brutally simple. When the default output is mediocre, people override it. Overriding is an act of migration: another tab, another app, another ecosystem. When the default output holds up, the override impulse weakens. That's the moment distribution becomes sticky. It's also the moment the destination starts paying an invisible tax: the tax of being the option you choose deliberately, while the other option shows up automatically. Alphabet's own numbers frame this as scale. Pichai, in his Q3 2025 remarks, said the Gemini app had "over 650 million monthly active users," and that queries "increased by 3x from Q2." He also said first-party models like Gemini were processing 7 billion tokens per minute via direct API use by customers. Take those figures for what they are: corporate statements delivered on an earnings call, meant to persuade. Even with that caveat, the direction is telling. Google is treating Gemini as a consumer product, an enterprise product, and an infrastructure product all at the same time -- because it can. It has enough surfaces to deploy across, and enough money to keep the lights on while use patterns harden into habit. Google's distribution only becomes destiny once its model quality clears the "good enough" threshold -- and right now, a lot of signals say it has. And that's important. A default that frustrates users is brittle. A default that performs competently becomes the path of least resistance. And the path of least resistance is where most people live. Google can pay patience bills. Google may be better positioned to make AI cheap at scale because it can optimize hardware, software, and distribution -- together. OpenAI can absolutely compete, but it has to keep locking down supply in a world where compute is strategy. Alphabet has been raising its capex forecast as demand for AI infrastructure accelerates, and 2026 is likely to carry an even larger bill. The AI-race winner won't just be the company with the smartest model. The winner will likely be the company that can subsidize the most intelligence, for the longest, without wrecking the core business that pays for the subsidy. Google has a cash engine built on intent (and ads). It knows how to monetize the moment someone wants something. OpenAI said it plans to begin testing advertising in the U.S. for ChatGPT's free and Go tiers, with the initial tests limited to logged-in adults. OpenAI's brand advantage is also its fragility -- the destination is where people form feelings, and feelings are easy to sour when money shows up near the answer box. Sure, ads might be a rational move for a company serving an enormous user base with escalating compute costs. But that move is also an admission that the economics of mass-scale AI are pushing everyone toward the same destination: ads, commerce, and whatever else can turn attention into margin. Google already lives there. Google already has a payment system for the entire internet. It's called Search. Heading into Wednesday's earnings call, the market is listening for whether Alphabet sounds like a company extending an empire or paying insurance premiums. Capex will be read as either disciplined investment tied to demand or a defensive spiral. Cloud commentary will be weighed for signs that AI infrastructure is becoming a durable growth engine rather than a margin-eating arms race. Search will be interpreted as either resilient in the face of interface change or quietly vulnerable to it. Maybe nobody "wins" the AI race. Maybe the market splits by context: Google dominates "built-in" everyday tasks; OpenAI dominates high-intent creative work; Anthropic's Claude dominates technical work; enterprises run mixed stacks; and the leader changes depending on whether you're coding, shopping, searching, writing, or automating. Maybe OpenAI figures out a way to leapfrog Alphabet -- Sam Altman's long-teased hardware push with Jony Ive turns into a device that ships at real scale and makes ChatGPT something you carry; Apple reverses course and lets someone else (or itself) run its AI; Microsoft $MSFT tightens, rather than loosens its grip on OpenAI inside Office and Windows. Maybe OpenAI could lock in the enterprise "before" the way Google owns the consumer one. Maybe, maybe, maybe. Or maybe not. OpenAI built the breakout product of the era. It proved the market. It trained users. It made "chat with a robot" feel normal. It also created an interface category that the incumbent with the biggest default footprint on Earth gets to absorb. In platform wars, the destination can be beloved and still lose. The default doesn't need to be beloved. It needs to be present, competent, and paid for. Google has all three advantages sitting on top of one another. Wednesday's call won't end the war, but it will tell you something important: whether Alphabet is speaking like the company that already owns the next interface, or the company still negotiating for it.

[2]

Big Tech Faces the AI Innovator's Dilemma. | PYMNTS.com

By completing this form, you agree to receive marketing communications from PYMNTS and to the sharing of your information with our sponsor, if applicable, in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms and Conditions. For most of the twentieth century, the sound of work and study in America was the clickety‑clack of typewriter keys in offices, newsrooms and dorm rooms as hundreds of thousands of machines moved ink to paper using typewriter keys. By the late 1980s, Smith Corona sat at the center of that world. It was reported to have a 50% share of the typewriter market. Its reputation as a reliable, well‑managed manufacturer could be measured by strong sales, robust distribution channels and steady margins. Smith Corona's leadership team did exactly what great management teams with a dominant market position are trained to do. They listened to their best customers, doubled down on what they asked for and operated the business with a financial model that was familiar, predictable and profitable. Innovation consisted of incremental improvements at the margin: quieter machines with less clickety-clack, more and better fonts and typos that could be more easily corrected. When PCs came onto the scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Smith Corona team sort of shrugged it off. They were new, expensive and hard to use, regarded mostly as "luxuries" for engineers and hobbyists. Pouring capital into such a new and unproven PC market seemed like a bad idea, especially since not a single one of their customers asked for one. So why risk the distraction? A solid base of long-time, loyal, high-margin customers asking for more of the same but better made PCs look like a sideshow. That was, until the typewriter itself became the sideshow less than two decades after those so-called luxury toys came into the market. The late Clay Christensen would give that management logic a name. His 1997 book, The Innovator's Dilemma, found its way on the reading list of most every MBA syllabus. In that book, Professor Christensen describes how customer‑centric, financially rational behavior can lead great firms into irrelevance when challengers with new technology enter the market. His thesis is that those leaders can become structurally blind to the threat of emerging technologies. New technologies, when introduced, are typically clunky -- like the first iPhone that couldn't actually make and receive any calls -- and filled with friction. Those early adopters don't always signal a rush of fast followers. Read more: What Electric Vehicles, Impossible Foods and Buy Now, Pay Later Teach Us About Early Adopters Yet history shows that less-profitable, initially clunky innovations frequently become the catalysts for market redefinition, as emerging technologies introduce something better than the status quo to customers who never directly asked for something new. That same dilemma now faces the Big Five technology giants as they bring AI and agents into their business. Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta and Microsoft each have world-class technical talent and a track record of innovation. Each is already weaving AI into its existing products; many have been using machine learning for decades to improve the user experience. Each tells a compelling story about how AI will make its core businesses better. Each has pioneered new and better ways for consumers and businesses to engage. The more pressing question is whether any of them will treat AI the way Christensen said disruptive technologies must be treated. By allowing it to challenge and potentially disrupt the business models, P&Ls and organizational structures that pay the bills today. And leave a lot left over to fill the piggy bank. If there were ever a company facing its own modern day version of the innovator's dilemma, it's Google. It is the rare example of a firm that both invented the core technologies behind the current AI and agentic disruption and controls one of the most profitable business models in modern history. Google's AI bona fides are impressive. First, its technical contributions to AI are foundational. Google Brain and DeepMind did not merely adopt deep learning early, they helped define it. The 2017 Transformer architecture described in the "Attention Is All You Need" paper fundamentally rewired how machines process language, vision and sequence data. Nearly every frontier model -- Gemini, GPT-4 and 5, Claude, Llama -- is built on that architecture. DeepMind's AlphaFold solved a grand challenge of biology at scale, reshaping drug discovery and molecular science. Nobel Prizes in 2024 in Chemistry and 2025 in Physics tied directly to Google's AI research team underscore genuine scientific leadership. Alphabet today still makes its money the same way it always has: by selling and monetizing eyeballs through advertising. In Q3 of 2025, Google Services, which includes Search, YouTube, network ads and subscriptions, generated 85.1% of total revenue. Search alone contributed 55%. Even Google Cloud, now exceeding $43 billion in annual revenue, remains a minority business that has not changed the company's fundamental dependence on advertising. This matters because AI does not merely improve the search and discovery experience. AI and agents threaten to compress or eliminate the very behaviors that make search ads so lucrative. Agentic systems answer questions directly. They summarize, compare, recommend and increasingly act. Each step collapsed by AI removes page views, links, ads, keywords and bidding opportunities. The same technology Google invented to understand language better can dramatically reduce the opportunity for the monetization on which its ad business depends. Read more: When Chatbots Replace Search Bars, Who Wins at Checkout? This fork in the road to new and different ways of monetizing its platform is nothing new to Google, particularly in commerce. But prior attempts haven't ended well. For more than two decades, Google has tried and failed to move beyond being a click to a page on a website. Google Shopping never became a destination. It became just another version of advertising. Google Pay, after more than fifteen years, finally scaled distribution but remained infrastructure for banks and networks rather than the foundation for a merchant ecosystem. Time and again, when forced to choose between building a new economic engine and reinforcing advertising margins, Google stuck with the latter. Gemini represents the most serious test yet of whether that pattern can change. Today, Gemini sits atop a rebuilt Shopping Graph with roughly 50 billion product listings Google says are refreshed hourly. AI Mode allows conversational discovery that feels different from traditional search. Users can ask for recommendations, constraints, trade-offs and comparisons at the prompt the way they'd talk to a sales associate: a conversation rather than a string of keywords. With the Universal Commerce Protocol and agentic checkout flows announced at NRF, Google has moved one step closer to closing the discovery/purchase loop, allowing discovery, selection and payment without leaving the Google ecosystem. Chrome integration and tokenized GPay credentials push this further, reducing friction to near zero. In theory. Read more: Why 30 Million US Consumers No Longer Search This has all of the structural underpinnings of a marketplace. But organizationally and economically, Google still behaves like an advertising platform. Ranking logic, monetization incentives and merchant relationships are all optimized around performance marketing. Even zero-click conversion still functions as a pay-for-click model rather than a reimagining of commerce. To truly become a commerce platform, Google would need to govern transactions, manage disputes, handle returns and accept responsibility for outcomes. Not just route demand more efficiently. Doing so would mean shifting revenue from CPC and CPA toward transaction fees, merchant software and financial services. It would also mean accepting lower margins in exchange for structural diversification. That is the choice that Christensen warned incumbents struggle to make. Technology makes both paths possible. Google's incentives make one far more comfortable than the other. At least for now. Meta offers a much more direct version of the same story. Where Google at least seems to flirt with commerce, Meta has spent the past decade demonstrating their lack of success in escaping a business model that works very well. Meta is, at its core, an advertising platform. In 2025, roughly 98.9% of revenue came from what is called its family of apps, including Instagram. Reality Labs contributed barely more than one percent and continued to generate massive losses, with cumulative operating deficits approaching $80 billion by late 2025. No amount of spin can obscure the Meta reality. Advertising pays the bills and then some. And nothing else has come close to replacing it. What makes Meta's case interesting is not a lack of ambition. The company has repeatedly tried to invent its way out of advertising dependence. Hardware initiatives like Portal failed to gain traction. Payments efforts stalled. The Libra/Diem stablecoin project collapsed under regulatory pressure, partner unease and a flawed business premise. Betting the company (and name) on the metaverse vision consumed tens of billions of dollars but never translated into mass-market behavior. Even commerce features inside Instagram and Facebook Shops ultimately fed back into ads rather than standing alone as transactional platforms. AI and agents have not changed that dynamic. They seem to have only intensified it. That said, Meta's AI assets are impressive. Llama is an open foundation model family, with recommendation systems that analysts say operate at unmatched scale, along with sophisticated ad-ranking and creative tools. But nearly all of this capability is aimed at one objective: maximizing the efficiency and yield of advertising. And the result is hard to dispute. AI-powered ad products reached roughly a $60 billion annualized run rate in 2025, with measurable lifts in click-through, conversion and pricing. Smart glasses illustrate the same pattern. Once positioned as a step toward augmented reality, they are now framed primarily as an AI interface that keeps users inside Meta's ecosystem. The revenue model ultimately points back to monetizing eyeballs (literally) through ads, engagement and new ad formats rather than an independent platform business built to sustain commerce. For Meta, AI and agents do not threaten the core. They only strengthen it. Who knows, maybe we will see another name change soon: MetAI. Apple's innovator's dilemma is a puzzle because it looks so different from Google's or Meta's. Apple is not dependent on advertising. It does not monetize eyeballs. Its margins come from selling slick hardware at scale and embedding high‑margin services within its operating system to keep its users there. But that strength has also created a pattern of repeated, expensive near‑misses in AI‑driven categories where Apple should, on paper, have won. In fiscal 2025, Apple generated roughly $416 billion in revenue. The iPhone alone accounted for just over half. Services reached a record $109 billion, with gross margins north of 70%, making it the most profitable segment in the company. Yet nearly every dollar of Services revenue remains tethered to the installed base of devices. Apple's economic center of gravity still runs through the handset, and everything else exists to protect, enhance or extend that core. That thesis helps explain Apple's uneven history with AI. Read more: Why Generative AI Is a Bigger Threat to Apple Than Google or Amazon Take Siri. Launched in 2011, Siri had an early lead over Google Assistant and Amazon Alexa and had every opportunity to nail voice and become a trusted voice assistant. But Apple treated Siri as a feature rather than a platform for connecting the user with services and apps within its ecosystem. And a pretty poor one at that. Not surprisingly, Siri stagnated. By the time large language models reset user expectations for conversational intelligence, Siri had become shorthand for the not-so- smart assistant that users largely rejected. Apple's AI struggles extend well beyond Siri and voice. The company spent nearly a decade and billions of dollars on Project Titan, its autonomous and electric car initiative, only to shut it down in early 2024. The project cycled through leadership changes, shifting goals and strategic resets, never resolving whether Apple was building a vehicle, a self‑driving system or a broader mobility platform. Ultimately, it produced no new revenue stream and no new platform. Home and ambient computing tell a similar story. HomePod never became the control panel for the home. Apple TV remained a content endpoint, not a broader services hub. Despite tight hardware integration and a loyal customer base, Apple failed to turn the home into a meaningful AI surface where assistants, commerce and automation converged. Payments show both Apple's strengths and its limits. Apple Pay and Wallet achieved massive global penetration as credential and tokenization layers. Apple Card and Apple Pay Later extended that footprint modestly. But Apple stopped short of building a full merchant services stack, a commerce marketplace or an AI‑driven purchasing layer that could compete with Amazon. Payments remained infrastructure, not a platform. Read more: The One Big Thing Apple's Project Breakout Needs but Doesn't Have Search is another glaring absence. Apple controls one of the most valuable distribution platforms in consumer computing, yet it never seriously attempted to build a general‑purpose search engine or AI discovery layer of its own. Instead, it has relied on multibillion‑dollar payments from Google to keep Google Search as the default on Safari. That arrangement is enormously profitable in the short term, but it left Apple without deep institutional experience in search, just as AI began to redefine those functions. GenAI exposed the cumulative effect of these choices. As large language models became the new interface for search, assistance, and conversion, Apple lacked a frontier‑class general‑purpose model of its own. We see this deficiency playing out now in real time as Apple continues to lose key AI talent and multiple attempts to launch Apple Intelligence have turned into an oxymoron for this $4 trillion company. Read more: Apple's $10B AI Crisis. 3 Bold Moves To Reinvent Its Future The decision to partner with Google and use Gemini as the backbone for a dramatically upgraded Siri is regarded as a Hail Mary move designed to shore up Apple's weakest flank and preserve the relevance of the iPhone and Services ecosystem. But it also confirms that Apple is renting intelligence rather than owning it. AI, in this configuration, is a defensive layer wrapped around an existing business model, not a force reshaping it. Apple's dependence on hardware, notably smartphones, is clear. And its innovator's dilemma is a strategic challenge that Tim Cook's successor will inherit. Amazon is often described as the best‑positioned company for an AI‑driven future because it already operates a global commerce, logistics and cloud infrastructure at extraordinary scale. And it has a long history of using AI and machine learning to make the engagement with its platform stakeholders more engaging and profitable. But Amazon's starting point in commerce could end up being both its greatest advantage and its greatest constraint. By 2025, Amazon generated roughly $715 billion in annual revenue. Retail remains the largest top‑line contributor, but AWS and advertising account for a disproportionate share of operating income. And its $68.2 billion advertising revenue is almost pure profit. Amazon already rebuilt commerce around data, automation and algorithms long before generative AI arrived. AI is fully embedded in pricing, search ranking, inventory placement, fulfillment routing, fraud detection and advertising. And there there's Alexa. When Alexa launched, it defined the modern voice assistant category. I was one of its earliest and most enduring fan girls. It seemed like such a powerful platform and launch pad for moving Alexa into the physical world and expanding the Amazon footprint. Read more: How Consumers Want to Live in a Conversational Voice Economy Amazon, with Alexa, was first to scale dedicated voice hardware into tens of millions of homes and hundreds of millions of devices. Buick once advertised the value of its car around its integration with Alexa in the cockpit. The ambition was explicit: Amazon's Alexa would become the consumer's virtual personal assistant for shopping, services and daily life. As a voice assistant, Alexa was pretty good at telling the time, the temperature and the occasional bad Dad joke. It was great at taking orders like setting timers, turning the lights on and off and opening and closing the blinds. Yet its ability to cross the proverbial chasm to shopping and commerce proved disappointing, even when Alexa was embedded in a device with a screen. Consumers began to lose trust. The skills ecosystem failed to mature into a vibrant marketplace to be monetized. Alexa lost momentum. Internally, Alexa became a costly initiative with weak direct revenue, reportedly generating tens of billions of dollars in cumulative losses. Amazon began cutbacks in its hardware and Alexa business units in later 2022 and continuing into the Spring of 2025. Hardware complicates the picture further. Amazon has never cracked consumer hardware economics. Echo speakers were subsidized to drive adoption and engagement of Alexa. As AI assistants and agents become embedded into phones, cars, wearables and operating systems, the standalone smart speaker will become the technological equivalent of the dodo bird. AI and agents will be ambient and live where screens, sensors and identity already exist. That's not in plastic cylinders on kitchen counters. Now, GenAI and agentic have given Amazon and Alexa a different opportunity to reclaim lost ground. Rufus, embedded in the Amazon app as a shopping assistant, plays to mixed reviews. With 250 million users and claims by Amazon of improving conversion by 60%, users seem to either love it or hate it. Alexa+, announced as a generative upgrade, promises richer conversation, task execution and orchestration across services. The jury is still out. My own experiences with Alexa+ have been mostly mixed. Both Rufus and Alexa+ are structurally optimized for Amazon's own commerce rails. Alexa and Rufus both route demand inside of Amazon's ecosystem, not across and outside of it. And, wisely in my opinion, Amazon has shut off access to its ecosystem from AI models. Amazon is a destination with consistent access to billions of SKUs. And it has a track record of connecting AI and agents to purchase and conversion within it, even if Rufus can be annoying at times. So, this is where Amazon's innovator's dilemma becomes interesting. To become the Super Agent for daily life, Alexa would need to operate across ecosystems, booking services, sourcing products, managing tasks and executing payments whether or not they are inside of Amazon's ecosystem. Monetized in some way, either tied back to Fulfillment by Amazon or using its Amazon Pay wallet to monetize the transaction. Amazon's challenge is not technical. The company knows how to build and scale new business units and monetize them. And they have done so well with AWS. But doing so required separating AWS from retail economics and allowing it to serve a broad ecosystem of companies, including competitors. Alexa and Rufus have not been given that freedom. Microsoft's position with AI and agents is often described as the strongest on paper. It owns Azure, the enterprise stack, and is paid massive amounts of money by LLMs to connect it to other models. It holds a big stake in OpenAI. And yet Microsoft's AI story, so far, is one of more of the same rather than reinvention. Copilot sells more feature-rich Microsoft 365 bundles. GitHub Copilot sells more subscriptions. Azure sells more compute. Read more: The Existential Threat That Microsoft Missed -- and Could Put Its GenAI Future at Risk Microsoft has laid AI tracks everywhere. It has good, powerful engines and an installed base of users. But it is still running trains on routes defined by old workflows. AI makes those workflows faster and better. But is does not yet reshape how value is created or captured. Investors sense this tension. Massive capital expenditure raises questions about whether AI is generating new demand. Microsoft has the assets to do more. What it lacks, so far, is the willingness to let AI redefine its business boundaries and the business models to support it. Read more: Why Measuring the ROI of Transformative Technology Like GenAI Is So Hard Smith Corona didn't disappear because it ignored innovation. It disappeared because it optimized relentlessly for the business and margins it already had. Their innovator's dilemma was not having the stomach needed to change course and a plan to creatively destruct itself, even though its best customers weren't asking for anything different. The innovator's dilemma for Big Tech looks different. Then again, it may not be the right lens at all. None of them have behaved like incumbents afraid to disrupt themselves. Google bet early and heavily on the core technologies behind modern AI, and is winning big. Amazon took a real swing at ambient computing with Alexa and Echo, a bet that looks less like complacency and more like a BlackBerry or early Microsoft moment where execution determined the less-than-stellar outcome. Apple swung for the fences as well, from Siri to autonomy to ambient computing, but struggled to turn its ambition into an enduring commerce platform. Maybe the lesson here isn't whether the Big Five are willing to change. But whether they can adapt agents and new AI flows fast enough to reshape how commerce in an agentic world works. And how they make money. Join the 19,000 subscribers who've already said yes to what's NEXT. PYMNTS CEO Karen Webster is one of the world's leading experts in payments innovation and the digital economy, advising multinational companies and sitting on boards of emerging AI, healthtech and real-time payments firms, including a non-executive director on the Sezzle board, a publicly traded BNPL provider.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Google is winning the AI chatbot race not through viral demos, but by embedding Gemini into its ecosystem of Search, Chrome, and Android. With 89.8% search market share and 71.4% browser dominance, Google transforms AI from a destination into default behavior. Yet this strategy forces the tech giant to confront the Innovator's Dilemma as it risks disrupting its own advertising-driven business model.

Google Gemini Transforms AI Integration Into Default Behavior

The AI chatbot race has evolved beyond viral demos and slick interfaces into a battle for default behavior. While OpenAI's ChatGPT captured attention as a famous destination, Google is embedding Gemini directly into the infrastructure billions already use daily

1

. The strategy leverages Google's dominant market position: 89.8% of global search engine market share in January, Chrome's 71.4% browser usage, and Android powering 70.4% of mobile operating systems1

. These numbers reveal how Google can turn new behaviors into reflexes without requiring users to change their routines.

Source: Quartz

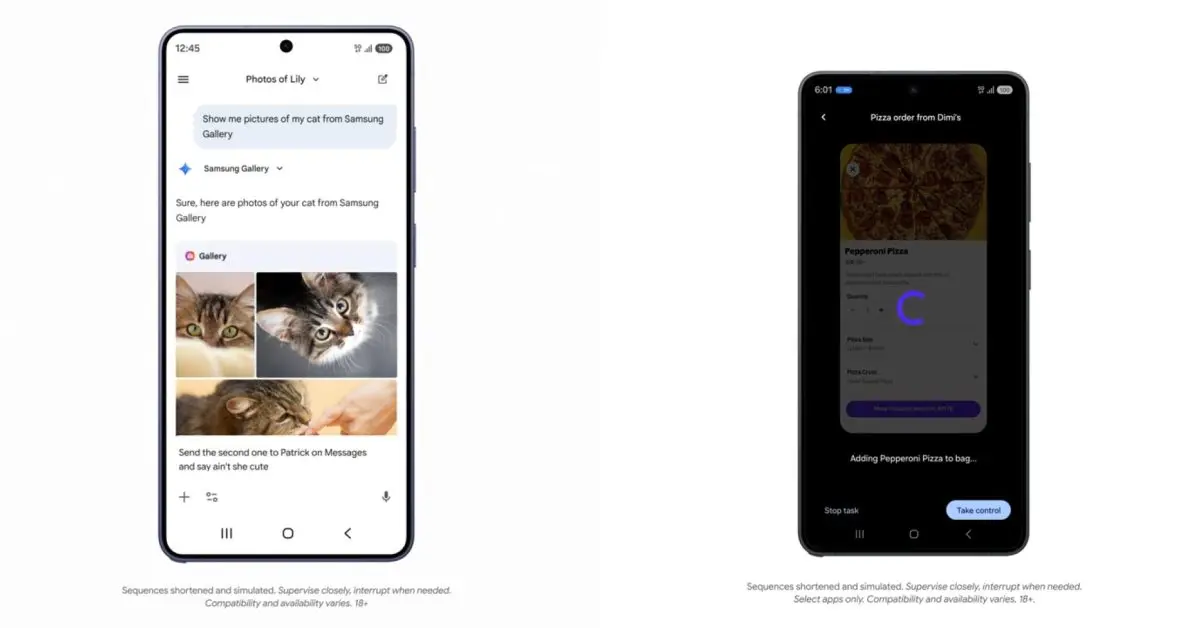

Google began integrating Gemini directly into Chrome last fall, introducing features designed to synthesize content and answer questions within browsing sessions

1

. CEO Sundar Pichai framed the company's approach during Alphabet's Q3 2025 earnings call as "reimagining Chrome as a browser powered by AI through deep integrations with Gemini and AI Mode in Search"1

. This AI integration strategy threads models into existing user motions across Search, Gmail, Maps, Workspace, Calendar, and YouTube, making "ask the machine" feel like using the internet itself.Apple recently announced a multiyear partnership to integrate Google's Gemini models, further expanding the ecosystem and distribution channels

1

. The partnership signals that Big Tech players recognize Google's infrastructure advantage in the AI landscape.Big Tech Confronts the Innovator's Dilemma With AI

Google's technical credentials in AI are foundational. The company's research teams invented the Transformer architecture described in the 2017 "Attention Is All You Need" paper, which underpins nearly every frontier model including GPT-4, GPT-5, Claude, and Llama

2

. DeepMind's AlphaFold solved grand challenges in biology, reshaping drug discovery and molecular science, with Nobel Prizes in Chemistry in 2024 and Physics in 2025 tied directly to Google's AI research team2

.

Source: PYMNTS

Yet Google faces what Clay Christensen termed the Innovator's Dilemma in his 1997 book

2

. The thesis describes how customer-centric, financially rational behavior can lead great firms into irrelevance when challengers introduce disruptive technology. In Q3 2025, Google Services—including Search, YouTube, network ads and subscriptions—generated 85.1% of total revenue2

. Google's advertising revenue remains the engine driving profitability, creating tension between innovation and protecting existing business models.The question facing Google and other Big Tech companies like Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Meta is whether they will allow AI to challenge the organizational structures and P&Ls that pay the bills today

2

. History shows that less-profitable, initially clunky innovations frequently become catalysts for market redefinition, as emerging technologies introduce something better than the status quo to customers who never directly asked for something new.Related Stories

Why Defaults Beat Destinations in the AI War

The AI war isn't a single battle but a stack of habits

1

. People don't wake up thinking about adopting an AI assistant; they search, scroll, browse, tap home screens, open documents, and refresh tabs. Google owns more of those motions than any company alive, threading its models into the motions themselves. OpenAI made AI feel like a place you can go, making new behavior mainstream fast through curiosity and magic1

. But Google doesn't need magic—it needs repetition.A destination wins when people make a deliberate trip; a default wins when people don't

1

. If the "ask the machine" moment happens inside the place users already start, the chatbot stops being something they seek out and becomes a behavior they perform. Google's entire business history demonstrates what happens when the default is everywhere and good enough to keep people inside the flow and advertisers paying for intent1

.The short-term implication is that Google can ship AI at the speed of its own update cycle, making "using Gemini" feel like "using the internet"

1

. The long-term question is whether monetization strategies will adapt as AI assistants live alongside browsing sessions, search sessions, and work sessions, potentially keeping users inside Google's ecosystem rather than sending them out onto the web. For OpenAI, the nightmare scenario is the most common starting point on the internet quietly growing a second brain1

. ChatGPT won the destination, but Google is building the default layer that the entire category runs on—and defaults have a way of becoming history.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Google's AI Renaissance: Alphabet Races Toward $4 Trillion Valuation as Gemini 3 Sparks Market Surge

24 Nov 2025•Business and Economy

Google Gemini secures Apple's Siri deal, positioning Alphabet to dominate the AI industry

15 Jan 2026•Technology

AI in 2024: Promises, Pitfalls, and the Path Forward

23 Dec 2024•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with Defense Production Act over AI military use restrictions

Policy and Regulation

2

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

3

Anthropic accuses Chinese AI labs of stealing Claude through 24,000 fake accounts

Policy and Regulation