King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard quits Spotify, only to be replaced by AI music clones

5 Sources

5 Sources

[1]

Musicians are getting really tired of this AI clone 'bullshit'

"Not ideal." "Completely unacceptable." "Shameless." "Predatory." "Some bullshit." "Total bullshit." This is how musicians, producers, and others in the industry are describing the relentless spread of AI clones. Of course, AI fakes aren't new, but as the scammers have gotten more brazen, artists are responding with increasing furor. We got a taste back in 2023 with multiple AI Drake tracks. But, in the last two years, the problem has gotten worse. Everyone from Beyoncé, to experimental composer William Basinski have had fake songs, likely generated by AI, appear to be streaming next to their names. And this week King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard found itself the latest target. Frontman Stu Mackenzie responded with anger, but also resignation, telling The Music, "we are truly doomed." Spotify has taken steps to address the issue, formalizing its policy against impersonation and removing 75 million spam tracks from its service. But the scale of the problem and the way the current system functions have made it difficult to rein in. Deezer says that 50,000 AI-generated tracks are uploaded to its library per day, accounting for more than 34 percent of the music it ingests. Bad actors take advantage of the fact that music isn't uploaded directly to Spotify and several other streamers; instead, it goes through a third-party distribution service like DistroKid. It's unclear what, if any, screening is in place to ensure that someone uploading a song is who they claim to be. (DistroKid did not respond to a request for comment.) This is how the seemingly AI-generated reggaeton song wound up on the Spotify page of William Basinski, an artist who specializes in ambient pieces built around the sounds of colliding black holes, crumbling tape loops, and shortwave radio broadcasts. "It's total bullshit," he told The Verge. "Luckily, my label and distributors keep an eye on these idiocies... What a mess." The response from Luke Temple of Here We Go Magic, whose dormant band was reactivated by AI impostors, was similar. Here We Go Magic haven't released new music since 2015, but after an AI track made its way onto the band's Spotify page, Temple told NPR that, "it is so awful." Similarly, when an AI-generated song called "Name This Night" appeared on the Spotify page for the band Toto in July, guitarist Steve Lukather called it "shameless" in a statement to Ultimate Classic Rock. Now, it's possible some of these fakes aren't AI, but AI makes it a hell of a lot quicker and easier to crank them out. While Suno is designed to ignore artist-specific prompts, it's still easy to generate entire songs with just a few words. Breaking Rust is not a clone of a specific artist, but Blanco Brown has accused the creator of modeling it on his vocals. Brown told the AP about someone texting him to let him know that "somebody done typed your name in the AI and made a white version of you. They just used the Blanco, not the Brown." Brown's manager, Ryan McMahan, took to LinkedIn, saying, "AI can run a formula. It cannot recreate Blanco's life experience that he pulls from. It cannot recreate the humanity, the conviction, or the lifetime of emotions that shaped his artistic voice." Breaking Rust generated attention by climbing to the top of the Billboard Country Digital Song Sales chart, resulting in misleading headlines about AI topping the country charts. But this is not the Country Streaming Songs or Hot Country Songs charts. The Song Sales chart measures things like iTunes purchases, and since hardly anyone actually buys songs on iTunes anymore, "Walk My Walk" was able to hit the top with only 3,000 purchases. It's possible that whoever is behind the song simply bought their way to the top. Solomon Ray, an AI gospel creation, enjoyed similar chart success and spurred backlash. Christianity Today said Ray "has no soul," a sentiment echoed by Christian artist Forrest Frank, who said on Instagram that, "AI does not have the Holy Spirit inside of it... It's really weird to be opening up your spirit to something that has no spirit." While Solomon Ray does not appear to be a direct clone, there is a real person, Solomon Ray, who is also a singer and a worship leader. Ray (the real one) told Christianity Today, "How much of your heart are you pouring into this? If you're having AI generate it for you, the answer is zero." In addition to composing with AI, some are trying to capitalize on the growing furor. A producer named Haven went viral after not-so-subtly suggesting that a song with AI-manipulated vocals was an unreleased Jorja Smith track. Of course, the vocals were not actually Smith's; they were processed using Suno, and the track was removed from streaming services. Harrison Walker (the man behind Haven) tried to cash in, rerecording the song and even trying to enlist Smith for a remix. Now, Smith and her label FAMM are demanding royalties from Haven. In a statement on Instagram, FAMM said that "creators are collateral damage in the race by governments and corporations towards AI dominance." The United Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW) has made no secret about where it stands, calling AI music "exploitation." Organizer Joey La Neve DeFrancesco told The Verge that "AI has given Spotify and the major labels the ability to fully cut out human artists and the royalties due to them. The streaming giant and the major labels have already cut deals with AI music companies." While some of the biggest labels like Warner are warming up to generative AI companies, musicians have found an ally in iHeartRadio. Company president Tom Poleman said on Instagram that "music is a uniquely human art form; creativity, storytelling, and soul that no algorithm can truly replicate." He pledged that the company would "never play AI-generated music with synthetic vocalists pretending to be human," and "never use AI-generated on-air personalities or podcasters." "Sometimes you have to pick a side, and we're on the side of humans," he concluded. Holly Herndon is more comfortable with AI than most musicians, having used it extensively, including on her album Proto. But even she has warned artists to be wary of exploitation. On an episode of The Most Interesting Thing in A.I., she said she brought many of her concerns around training data and artists' rights to some AI companies and "was blown away that they just weren't really thinking through this issue, they didn't think people would be upset about it." DeFrancesco says that, "It's clear that we need regulation to force streaming services to identify AI content and to remove it from streaming royalty pools." The United Musicians and Allied Workers is pushing for Congress to pass The Living Wage for Musicians Act, which it says would "protect artists from corporate AI exploitation," by creating a new royalty paid directly to musicians, by streaming platforms that "would only be paid out to human artists." For now, the onus is on the artists and their fans to be vigilant. Because, just like videos and photos, music needs to be approached with skepticism in the age of AI.

[2]

King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard quit Spotify in protest, only for an AI doppelgänger to step in

Imagine this: a band removes its entire music catalogue off Spotify in protest, only to discover an AI-generated impersonator has replaced it. The impersonator offers songs that sound much like the band's originals. The imposter tops Spotify search results for the band's music - attracting significant streams - and goes undetected for months. As incredible as it sounds, this is what has happened to Australian prog-rock band King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard In July, the band publicly withdrew its music from Spotify in protest at chief executive Daniel Ek's investments in an AI weapons company. Within months, outraged fans drew attention to a new account called "King Lizard Wizard". It hosted AI-generated songs with identical titles and lyrics, and similar-sounding music, to the original band. (And it isn't the first case of a fake Spotify account impersonating the band). The fake account was recommended by Spotify's algorithms and was reportedly removed after exposure by the media. This incident raises crucial questions: what happens when artists leave a platform, only to be replaced by AI knockoffs? Is this copyright infringement? And what might it mean for Spotify? As an Australian band, King Gizzard's music is automatically protected by Australian copyright law. However, any practical enforcement against Spotify would use US law, so that's what we'll focus on here. Is this copyright infringement? King Gizzard has a track called Rattlesnake, and there was an AI-generated track with the same title and lyrics. This constitutes copyright infringement of both title and lyrics. And since the AI-generated music sounds similar, there is also potential infringement of Gizzard's original sound recording. A court would question whether the AI track is copyright infringement, or a "sound-alike". A sound-alike work work may evoke the style, arrangement or "feel" of the original, but the recording is technically new. Legally, sound-alikes sit in a grey area because the musical expression is new, but the aesthetic impression is copied. Read more: Taylor Swift's Father Figure isn't a cover, but an 'interpolation'. What that means - and why it matters To determine whether there is infringement, a court would examine the alleged copying of the protected musical elements in each recording. It would then identify whether there is "substantial similarity" between the original and AI-generated tracks. Is the listener hearing a copy of the original Gizzard song, or a copy of the band's musical style? Style itself can't be infringed (although it does become relevant when paying damages). Some might wonder whether the AI-generated tracks could fall under "fair use" as a form of parody. Genuine parody would not constitute infringement. But this seems unlikely in the King Gizzard situation. A parody must comment on or critique an original work, must be transformative in nature, and only copy what is necessary. Based on the available facts, these criteria have not been met. False association under trademark law? Using a near-identical band name creates a likelihood of consumers being confused regarding the source of the AI-generated music. And this confusion would be made worse by Spotify reportedly recommending the AI tracks on its "release radar". The US Lanham Act has a section on unfair competition which distils two types of liability. One of these is false association. This might be applicable here; there is a plausible claim if listeners could reasonably be confused into thinking the AI-generated tracks were from King Gizzard. To establish such a claim, the plaintiff would need to demonstrate prior protectable trademark rights, and then show the use of a similar mark is likely to cause consumer confusion. The defendant in such a claim would likely be the creator/uploader of the AI tracks (perhaps jointly with Spotify). What about Spotify? Copyright actions are enforced by rights-holders, rather than regulators, so the onus would be on King Gizzard to sue. But infringement litigation is expensive and time-consuming - often for little damages. As Spotify has now taken down the AI-generated account, copyright litigation is unlikely. The streaming platform said no royalties were paid to the fake account creator. Even if this case was successfully litigated against the creator of the fake account, Spotify is unlikely to face penalties. That's because it is protected by US "safe harbour" laws, which limit liability in cases where content is removed after a platform is notified. This example demonstrates the legal and policy tensions between platforms actively promoting AI-generated content through algorithms and being "passive hosts". Speaking on the King Lizard incident, a Spotify representative told The Music: Spotify strictly prohibits any form of artist impersonation. The content in question was removed for violating our policies, and no royalties were paid out for any streams generated. In September, the platform said it had changed its policy about spam, impersonation and deception to address such issues. However, this recent incident raises questions regarding how these policy amendments have translated into changes to the platform and/or procedures. This is a cautionary tale for artists - many of whom face the threat of their music being used in training and output of AI models without their consent. For concerned fans, it's a reminder to always support your favourite artists through official channels - and ideally direct channels.

[3]

An AI copycat of King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard went unnoticed on Spotify for weeks

Despite making some moves to address the proliferation of AI-generated audio on its platform, Spotify failed to catch a copycat making imitations of music by King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard. The long-running experimental rock band from Australia, has been a vocal critic of Spotify and was one of several artists that took their music off the platform in the summer. The move was in response to the discovery that outgoing CEO Daniel Ek was a leading investor in an AI-focused weapons and military company. Today, a poster on Reddit was recommended what appeared to be an AI-generated copy of one of the band's songs in Spotify's Release Radar playlist. The phony artist was called King Lizard Wizard and it had an album of tracks all sharing titles with songs by the original band and using their original lyrics. Futurism grabbed screenshots of the imposter, although it appears to have since been taken down; only the band's original page appears in searches for both their name and the AI name. However, the phony King Gizzard band's album went unnoticed by the company for weeks before today's social post surfaced it. The Reddit thread points to several other anecdotal cases where someone attempted to trick listeners with AI-generated versions of popular bands. In September, Spotify unveiled a spam filter for catching AI slop, as well as policies for disclosing AI use in the content it hosts and how it would tackle AI impersonations. An instance like this, particularly when it features an artist that had left the platform in protest, creates a pretty big question mark about how well those policies are working.

[4]

'We are truly doomed': King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard despair at AI clone appearing on Spotify

Australian psych-rockers, who removed their music from Spotify in protest against the streaming service, lament the appearance of AI band King Lizard Wizard Spotify has removed an AI impersonator of popular Australian rockers King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard from the streaming service, with the band's frontman voicing despair at the situation. King Gizzard removed their music from Spotify in July in a protest against the company's chief executive Daniel Ek, who is the chair of military technology company Helsing as well as a major investor. Clearly attempting to fill the void, earlier this month a new artist appeared on Spotify called King Lizard Wizard, featuring AI-generated takes on the band's psychedelic rock, identical song titles, and AI-generated artwork that weakly imitated the band's fantastical album sleeves. Spotify has now removed King Lizard Wizard from its service, saying: "Spotify strictly prohibits any form of artist impersonation. The content in question was removed for violating our platform policies, and no royalties were paid out for any streams generated." Stu Mackenzie, King Gizzard's frontman, said he was "trying to see the irony in this situation" after the band's earlier departure from Spotify, but added: "Seriously wtf - we are truly doomed." AI-generated music is proving to be hugely contentious, and has quickly become one of the most discussed issues in the music industry. In September, Spotify announced it had removed 75m tracks thought to be made by AI artists last year, as fraudsters attempt to generate income by flooding the platform with fake artists who can generate royalty payouts. There have also been instances of "deepfake" versions of popular artists such as Drake being uploaded online. But while most of these tracks are caught in spam filters and never make it on to the platform, or are swiftly removed if they do, AI-generated or enhanced music is likely to become more popular. Currently in the UK Top 40 is I Run by British dance duo Haven, whose original version featured AI-manipulated vocals. Haven's Harrison Walker admitted to using AI, saying: "As a songwriter and producer I enjoy using new tools, techniques and staying on the cutting edge of what's happening." The song became a viral success but was removed from streaming services after takedown requests from labels and industry bodies alleging that the voice generated by AI too closely imitated British singer Jorja Smith. Haven then rerecorded I Run with human vocals, though Smith's label Famm alleges that both versions "infringe on Jorja's rights and unfairly take advantage of the work of all the songwriters with whom she collaborates". Haven have not responded to Famm's claim. AI-generated music is anticipated to enter the mainstream, though, when the tools become available to the general public. In recent weeks, major labels Universal and Warner have struck deals with the companies Udio and Suno, which will allow users to create AI music from the work of real artists signed to those labels (with artists able to opt in and out of making their music available). Speaking to the Guardian this week, Eurythmics producer Dave Stewart described AI in music as an "unstoppable force", and argued: "Everybody should be selling or licensing their voice and their skills to these companies." But others have voiced concern. After the deal between Universal and Udio, Irving Azoff, founder of the Music Artists Coalition in the US, warned that artists could "end up on the sidelines with scraps", adding: "Every technological advance offers opportunity, but we have to make sure it doesn't come at the expense of the people who actually create the music - artists and songwriters ... artists must have creative control, fair compensation and clarity about deals being done based on their catalogues."

[5]

King Gizzard Pulled Their Music From Spotify in Protest, and Now Spotify Is Hosting AI Knockoffs of Their Songs

"I find this absolutely deplorable and am now quitting my account." Acclaimed Australian prog rock band King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard joined a growing number of artists when it left Spotify in July. At the time, band leader Stu Mackenzie took aim at Spotify CEO Daniel Ek, excoriating him for investing in an AI weapons company. "We've been saying f*** Spotify for years," Mackenzie told the Los Angeles Times. "In our circle of musician friends, that's what people say all the time, for all of these other reasons which are well documented." But in a technological twist, impersonators are now using generative AI to clone the band's iconic sound. A user on Reddit was recently recommended a track on his Release Radar that was a clear knockoff of the real King Gizzard, alerting them to the scheme. The track spotted by the Reddit user, called "Rattlesnake," is listed under an artist with the incredibly similar name "King Lizard Wizard" -- which is striking, because the real King Gizzard also has a song called "Rattlesnake." The similarities don't end there: the fake version of the song, which is clearly AI-generated, has identical lyrics to King Gizzard's original version, along with a notably similar composition. In fact, every song uploaded by the knockoff "King Lizard" artist on Spotify has the same title as an actual King Gizzard song, with its corresponding lyrics ripped straight from the source, suggesting the perpetrator fed the lyrics into an AI music generator and instructed it to copy the band's sound. A quick search for "King Gizzard" on the platform brings up the band's abandoned official profile, with "King Lizard Wizard" being recommended immediately below it. The fact that Spotify has let the knockoff band proliferate on its platform -- where it's accumulated tens of thousands of streams since uploading the tracks last month -- is especially egregious because King Gizzard has already been targeted by impersonators on its service. As Platfomer reported last month, Spotify was previously overrun by another King Gizzard impersonator that uploaded "muzak" versions of the band's songs. In other words, if there's one band that Spotify should be manually monitoring for AI rip-offs, it's King Gizzard, but it's clearly making no such effort. Spotify didn't reply to a request for comment. The fake band's album art also appears to be AI-generated, and has been live on Spotify for weeks. Adding insult to injury, some of the fake tracks even list Mackenzie as the "composer" and "lyricist." A quick search for "King Gizzard" on the platform brings up the band's abandoned official profile, with "King Lizard Wizard" being recommended immediately below it. The top song result for the search is the AI band's ripped off version of "Rattlesnake." Unsurprisingly, the unsavory attempt at cashing in on a band that pointedly departed Spotify didn't sit well with many fans. "A bad AI ripoff, from aesthetics to band name, copying their songs," wrote the Reddit user who discovered the track on their Spotify account. "I find this absolutely deplorable and am now quitting my account." The incident highlights how Spotify is seriously struggling with content moderation in an age increasingly being defined by a barrage of AI slop. The company announced new policies to protect artists against "spam, impersonation, and deception" in September. But given the AI imitations that are still invading Release Radar and Discover Weekly playlists, which the company prominently recommends to its users, it's clear that the company is struggling to meaningfully address the issue. We've come across previous egregious examples, like a dubious track that claimed to be performed by Bon Iver frontman Justin Vernon's 2000s side project Volcano Choir -- but in reality was AI slop. While Spotify has said it will be cracking down on spam and impersonation, AI-generated music is technically allowed on the platform -- some of which has even turned out to be a major hit, with an AI country song even topping a digital Billboard chart.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Australian prog-rock band King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard removed their entire catalog from Spotify in July to protest CEO Daniel Ek's investments in AI weapons technology. Months later, fans discovered an AI-generated impersonator called 'King Lizard Wizard' hosting knockoff tracks with identical titles and lyrics. The fake account accumulated tens of thousands of streams before removal, exposing serious gaps in Spotify's content moderation despite new policies against artist impersonation.

AI Clones Exploit King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard's Spotify Absence

When King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard pulled their music from Spotify in July 2024, they made a statement against CEO Daniel Ek's investments in military AI technology. What they didn't anticipate was becoming victims of the very technology they opposed. Months after their departure, fans discovered an AI-generated impersonator operating under the name 'King Lizard Wizard' on the streaming platform, hosting tracks that mimicked the Australian prog-rock band's distinctive sound

1

4

. The fake account featured AI music with identical song titles and lyrics to the original band's work, including a track called 'Rattlesnake' that copied the band's actual song word-for-word5

. Frontman Stu Mackenzie responded with despair, telling The Music, 'we are truly doomed'1

.

Source: Engadget

Spotify's Content Moderation Struggles With AI-Generated Knockoffs

The AI-generated knockoffs went undetected for weeks before a Reddit user spotted the fake 'Rattlesnake' track in their Release Radar playlist, Spotify's personalized recommendation feature

3

. The impersonator's tracks accumulated tens of thousands of streams, with Spotify's algorithms actively recommending the AI clones to users searching for the real band5

. This incident is particularly troubling because King Gizzard had already been targeted by impersonators on Spotify before, raising questions about why the streaming platform wasn't monitoring the band more closely5

. After media exposure, Spotify removed the fake account, stating it 'strictly prohibits any form of artist impersonation' and confirmed no royalties were paid to the fake account creator4

. However, the incident highlights serious gaps in the platform's ability to enforce its own policies despite announcing new measures against spam and artist impersonation in September3

.Copyright Infringement and Trademark Law Implications

The King Lizard Wizard case raises significant legal questions around copyright infringement and trademark law. Using identical song titles and lyrics constitutes clear copyright infringement, while the similar-sounding AI music potentially infringes on the band's original sound recordings

2

. Courts would examine whether the AI tracks are direct copies or 'sound-alikes' that evoke the band's style without technically reproducing protected elements2

. The near-identical band name creates false association issues under trademark law, particularly when Spotify's algorithms recommended the fake tracks, potentially confusing consumers about the source of the music2

. While Spotify benefits from safe harbor laws that limit liability when content is removed after notification, this case exposes tensions between platforms actively promoting AI-generated content through algorithms while claiming to be passive hosts2

.Growing Wave of Artist Impersonation Across the Music Industry

King Gizzard joins a growing list of artists victimized by AI clones. Musicians from Beyoncé to experimental composer William Basinski have discovered fake songs appearing under their names on streaming platforms

1

. William Basinski, known for ambient pieces built around colliding black holes and crumbling tape loops, found an AI-generated reggaeton song on his Spotify page, calling it 'total bullshit'1

. Luke Temple of Here We Go Magic, whose band hadn't released new music since 2015, discovered AI tracks reactivating their dormant Spotify page, telling NPR 'it is so awful'1

. The scale of the problem is staggering: Spotify removed 75 million spam tracks last year, while Deezer reports that 50,000 AI-generated tracks are uploaded to its library per day, accounting for more than 34 percent of the music it ingests1

4

.

Source: The Conversation

Related Stories

Distribution Service Vulnerabilities Enable AI Music Fraud

Bad actors exploit a fundamental vulnerability in how streaming platforms operate. Music isn't uploaded directly to Spotify; instead, it passes through third-party distribution services like DistroKid

1

. It remains unclear what screening measures, if any, exist to verify that someone uploading a song is who they claim to be1

. Generative AI tools like Suno and Udio have made creating convincing sound-alikes easier than ever, allowing anyone to generate entire songs with just a few text prompts1

. While Suno is designed to ignore artist-specific prompts, the King Lizard Wizard case demonstrates how perpetrators can feed lyrics and style instructions into AI music generators to create deepfake versions of existing artists5

. The fake tracks even listed Stu Mackenzie as the composer and lyricist, adding another layer of deception5

.

Source: Futurism

Ethical Concerns and the Future of AI in the Music Industry

The incident raises profound ethical concerns about AI's role in music creation and distribution. Producer Haven's Harrison Walker faced backlash after creating a viral track with AI-manipulated vocals that too closely imitated British singer Jorja Smith, leading to takedown requests and demands for royalties from Smith's label FAMM

1

4

. An AI gospel creation called Solomon Ray sparked particular controversy, with Christianity Today saying it 'has no soul' and Christian artist Forrest Frank questioning the spiritual authenticity of AI-generated worship music1

. Meanwhile, major labels Universal and Warner have struck deals with Udio and Suno, allowing users to create AI music from real artists' work, with artists able to opt in or out4

. Irving Azoff, founder of the Music Artists Coalition, warned that artists could 'end up on the sidelines with scraps' without proper protections ensuring creative control, fair compensation, and clarity about deals based on their catalogs4

. As AI detection policies struggle to keep pace with rapidly evolving technology, the music industry faces critical decisions about balancing innovation with protecting artists' rights and livelihoods.References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

[4]

Related Stories

AI-Generated Music Sparks Controversy: Fake Albums and Artist Impersonation on Streaming Platforms

26 Aug 2025•Technology

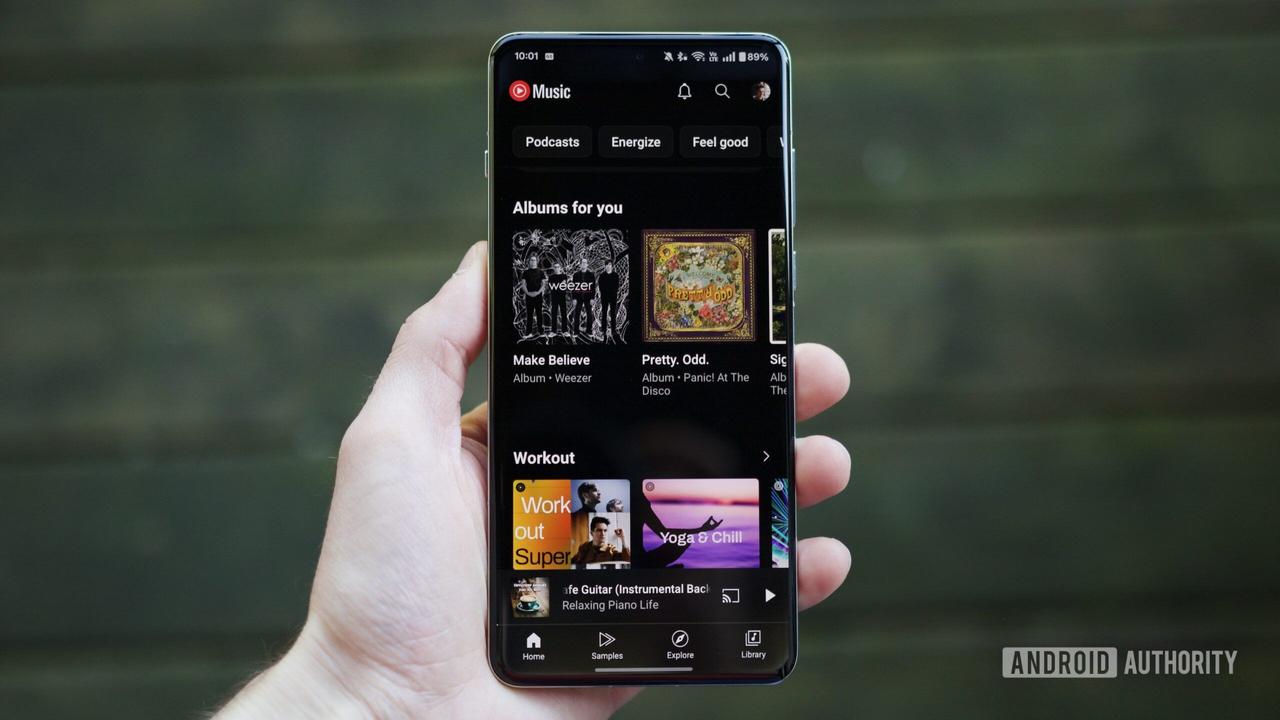

YouTube Music users furious as AI slop floods recommendations, threatening paid subscriptions

06 Jan 2026•Technology

AI-Generated Band "Velvet Sundown" Sparks Debate on Music Industry's Future

08 Jul 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic takes Pentagon to court over unprecedented supply chain risk designation

Policy and Regulation

3

Meta smart glasses face lawsuit and UK probe after workers watched intimate user footage

Policy and Regulation