AI Data Centers: The Massive Energy and Resource Demands Reshaping America's Infrastructure

7 Sources

7 Sources

[1]

AI Data Centers Are Coming for Your Land, Water and Power

From the outside, this nondescript building in Piscataway, New Jersey, looks like a standard corporate office surrounded by lookalike buildings. Even when I walk through the second set of double doors with a visitor badge slung around my neck, it still feels like I'll soon find cubicles, water coolers and light office chatter. Instead, it's one brightly lit server hall after another, each with slightly different characteristics, but all with one thing in common -- a constant humming of power. The first area I see has white tiled floors and rows of 7-foot-high server racks protected by black metal cages. Inside the cage structure, I feel cool air rushing from the floor toward the servers to prevent overheating. The wind muffles my tour guide's voice and I have to shout over the noise for him to hear me. Outside the structure it's quieter but there's still a white noise that reminds me of the whooshing parents use to get newborn babies to sleep. On the back of the servers, I see hundreds of cords connected -- blue, red, black, yellow, orange, green. In a distant server, green lights are flashing. These machines, dozens of them, are gobbling electricity. In all, this building can support up to 3 megawatts of power. This is a data center. Facilities like it are increasingly common across the US, sheltering the machinery that makes our online lives not only possible, but nearly seamless. Data centers host our photos and videos, stream our Netflix shows, handle financial transactions and so much more. The one I'm visiting, owned by a company called DataBank, is modest in scope. The ones coming in one after another to suburban communities and former farmlands across the US, riding the tidal wave of artificial intelligence's swift advances, are monstrous. It's a building boom based on generative AI. In late 2022, OpenAI launched ChatGPT and within two months it had approximately 100 million users and had spurred a frantic scramble among the biggest tech companies and a host of newborn startups. Now, it has nearly 700 million active users each week and 5 million paying business users. We are inundated with chatbots, image generators and speculation about superintelligence looming in the not-too-distant future. AI is being woven into our everyday lives, from banking and shopping to education and language learning. Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, Microsoft and OpenAI are all spending massive amounts of money to drive that growth. The Trump administration has also made it clear that it wants the US to lead AI innovation across the globe. "We need to build and maintain vast AI infrastructure and the energy to power it," the White House said in July in a document called America's AI Action Plan, which calls for streamlined construction permitting and the removal of environmental regulations. "Simply put, we need to 'Build, Baby, Build!'" Building, and building big, is very much on the mind of Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg. He's been touting his company's plans for an AI data center in Louisiana, nicknamed Hyperion, that would be large enough to cover "a significant part of the footprint of Manhattan." All of that is adding up to an enormous demand for electricity and water to run and cool those new data centers. Generative AI requires energy-intensive training of large language models to do its impressive feats of computing. Meanwhile, a single ChatGPT query uses 10 times more energy than a standard Google search, and with millions of queries every day -- not just from ChatGPT but also from the likes of Anthropic's Claude, Google's Gemini and Microsoft's Copilot -- that's a staggering increase in the stresses on the US electrical grid and local water supplies. "Data centers are a critical part of the AI production process and to its deployment," said Ramayya Krishnan, professor of management science and information systems at Carnegie Mellon University's Heinz College. "Think of them as AI factories." But as data centers grow in size and number, often drastically changing the landscape around them, questions are looming: What are the impacts on the neighborhoods and towns where they're being built? Do they help the local economy or put a dangerous strain on the electric grid and the environment? On the outskirts of communities across the country -- and sometimes smack dab in the middle of cities like New York -- giant AI data centers are springing up. Meta, for instance, is investing $10 billion into its 4-million-square-foot Hyperion data center, planned to open by 2030. An explosion of construction is likely coming to Pennsylvania. In July, at an energy summit in Pittsburgh attended by President Donald Trump, developers announced upward of $90 billion for AI in the state, including a $25 billion investment from Google. Perhaps the most ambitious undertaking is unfolding under the auspices of a new company called the Stargate Project, backed by OpenAI, Oracle, Softbank and others. In late January, on the day that Trump was sworn in to his second term as president, OpenAI said that Stargate would invest $500 billion in AI infrastructure over the next four years. An early signature facility for Stargate, amid reports of early struggles, is a sprawling data center under construction in Abilene, Texas. OpenAI said last month that Oracle had delivered the first Nvidia GB200 racks and that they were being used for "running early training and inference workloads." The publication R&D World has reported that the 875-acre site will eventually require 1.2GW of electricity, or the same amount it would take to power 750,000 homes. (Disclosure: Ziff Davis, CNET's parent company, in April filed a lawsuit against OpenAI, alleging it infringed Ziff Davis copyrights in training and operating its AI systems.) Currently, four tech giants -- Amazon Web Services, Google, Meta and Microsoft -- control 42% of the US data center capacity, according to BloombergNEF. The sky-high spending on AI data centers has become a major contributor to the US economy. Those four companies have spent nearly $100 billion in their most recent quarters on AI infrastructure, with Microsoft investing more than $80 billion into AI infrastructure during the current fiscal year alone. Not all data centers in the US handle AI workloads -- Google's data centers, for instance, power services including Google Cloud, Maps, Search and YouTube, along with AI -- but the ones that do can require more energy than small towns. A July report from the US Department of Energy said that AI data centers, in particular, are "a key driver of electricity demand growth." From 2021 to 2024, the number of data centers in the US nearly doubled, according to report from Frontier Group, the Environment America Research & Policy Center and the U.S. PIRG Education Fund. And according to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the need for data centers is expected to increase by 9% each year until at least 2030. By 2035, data centers' US electricity demand is expected to double compared with today's. Here's another way to look at it: Speaking before the Senate Commerce Committee in May, Microsoft President Brad Smith said his company estimates that "over the next decade, the United States will need to recruit and train half a million new electricians to meet the country's growing electricity needs." As fast as the AI companies are moving, they want to be able to move even faster. Smith, in that Commerce Committee hearing, lamented that the US government needed to "streamline the federal permitting process to accelerate growth." This is exactly what's happening under the Trump administration. Its AI Action Plan acknowledges that the US needs to "build vastly greater energy generation" and lays out a path for getting there quickly. Among its recommendations are creating regulatory exclusions that favor data centers, fast-tracking permit approvals and reducing regulations under the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. One step already taken: The Trump administration rescinded a Biden administration executive order -- outlining the need to ensure AI development and use was done ethically and responsibly -- to reduce "onerous rules imposed." Early this year, June Ejk set up the Facebook page called Concerned Clifton Citizens to keep her neighbors informed about the happenings in Clifton Township, Pennsylvania. Now, her main focus is stopping a proposed 1.5GW data center campus from coming to the area that she's called home for the past 19 years. The developer, 1778 Rich Pike, is hoping to build a 34-building data center campus on 1,000 acres that spans Clifton and Covington townships, according to Ejk and local reports. That 1,000 acres includes two watersheds, the Lehigh River and the Roaring Brook, Ejk says, adding that the developer's attorney has said each building would have its own well to supply the water needed. "Everybody in Clifton is on a well, so the concern was the drain of their water aquifers, because if there's that kind of demand for 34 more wells, you're going to drain everybody's wells," Ejk says. "And then what do they do?" Ejk, a retired school principal and former Clifton Township supervisor, says her top concerns regarding the data center campus include environmental factors, impacts on water quality or water depletion in the area, and negative effects on the residents who live there. Her fears are in line with what others who live near data centers have reported experiencing. According to a New York Times article in July, after construction kicked off on a Meta data center in Social Circle, Georgia, neighbors said wells began to dry up, disrupting their water source. The data center Ejk is hoping to stop hasn't yet been approved -- the developer has to get zoning ordinances amended and signed off on before moving forward -- but Covington Township has shown an interest in the project moving forward. For her part, Ejk has created and shared a "say no to a data center in our community" flyer with a call-to-action for her fellow citizens to attend monthly board of supervisors meetings for discussions on the topic. "I worry about the kind of world I'm leaving for my grandchildren," Ejk says. "It's not safer, it's not better, and we're selling out to these big corporations. You know, it's not in their backyard, it's in my backyard." If one or both of the townships do decide to move forward with the project, Ejk won't stop there. "I'm going to be telling residents to get your wells tested now, because if, after [the data centers] are built and the quality of your water changes, you will have to have a basis of what changed," she said. In Louisiana, some residents are welcoming Meta's planned data center in Richland Parish, the one that Zuckerberg says would cover a large part of Manhattan. Others, like Julie Richmond Sauer, believe it could harm the entire state. The facility will be located between the towns of Rayville, population of roughly 3,300, and Delhi, population 2,500. "It is 2,250 acres of farmland that will never be farmed again," Sauer, a registered nurse in central Louisiana, tells me. "That, of course, is a concern of mine, for my children and my grandchildren one day." She also thinks job development, a key selling point for data centers, is often overestimated. "It was sold by our legislators as, 'Hey, we're getting jobs,' which sounds wonderful. 'We're bringing industry in,' which sounds wonderful, but then the more I'm reading, it looks like 500 jobs max," Sauer says, who compared the amount with a medium-size hospital. Louisiana Economic Development, a state agency, expects the data center to bring in 500 "direct jobs," or permanent ones, to the area, along with 1,000 "indirect" jobs and 5,000 construction and temporary jobs at its peak. It's unclear if those construction jobs would go to locals or to workers brought in temporarily from elsewhere. Meanwhile, OpenAI is pitching vastly more jobs for 4.5GW of Stargate data center capacity in the US, should it ever come to pass: 100,000 jobs, "spread across construction and operations roles." But it also acknowledges that the construction jobs would be "short-term." "I just don't think it's enough to sell your soul for," Sauer says. "They have only sold the positives in this and not told the public the negatives, and that's a fact." She believes ultimately that the decision on where to put these data centers should fall on a statewide public vote. There are currently more than 5,000 data centers in the US. While no state is completely free of these computing facilities, some states, such as Virginia, have become magnets for them. Ashburn, Virginia, alone boasts 140 data centers of the more than 500 in the state, earning the area the nickname "Data Center Alley." Texas and California, meanwhile, have more than 300 each. Virginia is attractive for data centers thanks to tax incentives, fiber optic infrastructure and a skilled workforce. Other states are actively trying to attract data centers by offering incentives, too. But concerns are rising regarding these tax breaks and who ends up picking up the bill. "More than 20 states are offering tax breaks to data centers in an effort to incentivize them to come to their state," Quentin Good, a policy analyst at Frontier Group, tells me. "So data centers are often given exemptions on things like the sales tax for all of the equipment that they need to fill up their data centers, and that ultimately falls on taxpayers to pay for the cost of those tax breaks." No matter where they're located, all data centers require a lot of power. According to the International Energy Agency, the US accounted for the largest share of global data center electricity consumption in 2024, at 45%. The Trump administration has emphasized the need to strengthen the grid to support the coming tidal wave of data centers. The president has gone so far as to declare the situation a national energy emergency. "The United States is experiencing an unprecedented surge in electricity demand driven by rapid technological advancements, including the expansion of artificial intelligence data centers and an increase in domestic manufacturing," an April executive order reads. To combat this issue, the government wants to use all available power sources, monitor the US electricity supply closely and follow the new AI Action Plan. "We've [previously] had really stable electricity demand increases of like 2% or 3%, but with a recent boom in data centers and the electrification of other things, like our homes and our vehicles, the [projected] demand for electricity is starting to jump up dramatically," Good says. Last month, a report from the Department of Energy warned that updates to the country's electric grid are imperative for grid reliability caused by AI's escalating demands. "Absent intervention, it is impossible for the nation's bulk power system to meet the AI growth requirements while maintaining a reliable power grid and keeping energy costs low for our citizens," the report says. AI's growth and the need for more data centers to support it are rapidly increasing the stress on the US energy grid. This strain is causing "a lower system stability," the North American Electric Reliability Corporation's 2025 State of Reliability found. The US energy grid, built in the 1960s and '70s, was not designed to handle the energy pull AI is creating. At the end of 2023, the US energy grid -- which supports every request for electricity, from your home's lighting and air conditioning to massive industrial processes -- could handle about 1,189 gigawatts. Meta's Hyperion, for example, will have a capacity of 2 gigawatts, or 2,000 megawatts. That's a roughly 30 times greater demand for electricity than at DataBank's EWR2 location. "What we're seeing with new data centers is just the size difference," John Moura, NERC's director of reliability assessment and performance analysis, tells me. "For the past decade, we've probably seen a couple hundred megawatts as kind of your largest ones. Now we see interconnection requests for one or two or, I think I heard about 5-gigawatt requests, and that really changes the fundamentals of how the system is planned." The Alliance for Affordable Energy is challenging Meta's Louisiana data center -- calling it "a power-hungry giant" -- along with Entergy Louisiana's bid to build three gas plants to power it. Citing expert testimony, the group is sounding the alarm about a potentially debilitating strain on the electric grid and the cost to the citizens of Louisiana. "It's not exactly black and white in terms of who's paying for the [data center's] upgrades that are needed," Good says, adding that utilities have an obligation to serve all customers. "If any customer moves into their service area, they have to meet that customer's needs in terms of electricity." So, regardless of the scale of a data center, if they get approved to build in any town, the utility must provide the energy needed to power it. A large customer moving into the area could also cause a "short-term constraint on the supply of energy." "That's going to push utility prices up for everyone who's a customer of that utility," Good says. A study by Carnegie Mellon University and North Carolina State University, published in June, says that electricity rates could rise 8% on average across the US through 2030 because of increased demand from data centers, along with cryptocurrency generation. Electricity rates in northern Virginia, a hub of data center activity, could jump more than 25%. In a bid for additional energy sources, tech companies are turning to nuclear power as a possible solution, but Moura says nuclear power is still at least "a couple of years out." "In the next five years, there's not too many options to build generation, and so [energy] storage can help, but it's not a source of generation," Moura says. Meta has said it will begin using nuclear energy in 2027, with Amazon and Google hoping to use nuclear energy sometime in the 2030s. The water consumption of these data centers, specifically ones that help power AI, has been top of mind for many. Data centers use water to cool the servers. This use is something that tech companies have tried -- and often failed -- to keep quiet. In 2022, after the newspaper The Oregonian sought records about Google's water use for a data center in The Dalles, the Oregon city sued to stop the paper from releasing the information. Eventually, the paper did receive the information, which revealed that in 2021, the Google data center used a staggering 355 million gallons of water, which is roughly equal to 538 Olympic-size swimming pools. The Oregonian's reporting helped shine a light on the natural resources these data centers need to run, and, maybe more important, it opened the question of whether our finite resources can handle the demand. According to Google's 2024 environmental report, the company's location that used the most water in 2023 was Council Bluffs, Iowa, home to two data centers, one built in 2007 and the other in 2012. In 2023, the Council Bluffs facilities sucked in 1.3 billion gallons of water from the local water supply. Google spent $1 billion in 2024 to expand the facility, and that year the intake rose to 1.4 billion gallons. Meta's 2024 sustainability report doesn't break down water use by data center; it just gives an aggregate number. In 2023, its data centers worldwide took in 1.39 billion gallons of water. Just less than 50% of that was permanently removed from local water sources. Between 2019 and 2023, Meta's data center water withdrawal increased by roughly 43%, but it still uses significantly less water than Google's data centers as a whole. When data centers consume water, a significant amount evaporates during the cooling process. The remaining water, which is often polluted, is put into the city's wastewater system. Both companies have stated they plan to be "water positive" by 2030, meaning they want to return more water to the communities than what the data centers consume through water recycling, reusing and water replenishment projects. However, returning water to the exact source the data center drew from is not always possible. Instead, Google states it attempts to improve additional water sources in the area, restore wetlands and recycle treated wastewater in an effort to counter its water usage. Even as big tech companies invest heavily in AI, they also continue to promote their sustainability goals. Amazon, for example, aims to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040. Google has the same goal but states it plans to reach it 10 years earlier, by 2030. With AI's rapid advancement, experts no longer know if those climate goals are attainable, and carbon emissions are still rising. "Wanting to grow your AI at that speed and at the same time meet your climate goals are not compatible," Good says. For its Louisiana data center, Meta has "pledged to match its electricity use with 100% clean and renewable energy" and plans to "restore more water than it consumes," the Louisiana Economic Development statement reads. However, questions remain around these promises. US Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island, the top Democrat on the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, questioned Meta and Zuckerberg in an official inquiry in May, labeling those climate pledges as "vague." Whitehouse said he believes Meta is putting the need for data centers and natural gas generation "over climate safety." Meta has not yet responded. Google's 2025 Environmental Report shows a 51% increase in carbon emissions in 2024 compared with 2019, despite its sustainability efforts outlined in the report. DataBank, although smaller in scale, also has a sustainability goal tied to its more than 65 locations. It plans to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2030. Jenny Gerson, DataBank's sustainability chief, tells me that DataBank has decreased emissions through "procuring renewable power on the grid" and is looking at alternative fuel sources to replace diesel fuel, including hydro-treated vegetable oil. "So instead of pulling more fossil fuels out of the ground and burning them, you're using a plant-based source that has a much shorter carbon cycle and leaving the fossil fuels in the ground," Gerson explains. DataBank is also prioritizing minimizing energy use by switching to LED lightbulbs throughout its data centers, optimizing air flow to keep cool air around the servers and using closed-loop water systems, "meaning you fill the loop once, and then whatever water or glycol is in there remains in there, and you do not consume more water," she says. Microsoft is currently transitioning new data centers to closed-loop systems. Other possible solutions include creating flexible data centers, meaning they can pull less energy from the grid when energy usage in the surrounding community is expected to be high, such as during a heat wave or when severe weather is incoming. Meta and Google are founding members of the Electric Power Research Institute's DCFlex initiative, which aims to make more data centers flexible and help the energy grid remain reliable. "Obviously, everyone wants to use the internet, they want to use AI, and we need to do it responsibly," Gerson says. "So how can we as players do that? And a lot of that is making sure we're doing it through renewable power." There's at least one data center in each US state, and plenty more are on the horizon. If you don't live near one now, there's a good chance you will soon. If you live in an area that isn't prone to natural disasters and boasts natural resources, such as an abundance of water or robust wind, tech companies may be eyeing the spot for an AI factory. Google tells me it has "a very rigorous process to select sites, which includes factors like proximity to customers and users, local talent, land, a community that's excited to work with us and availability of (or potential to bring new) carbon-free energy." The Trump administration's AI Action Plan emphasizes the need for more data centers, electricians and HVAC technicians for the US to win the AI race. Many of the new data centers being built are massive and impossible to miss. There will be smaller ones as well, like Databank's EWR2 facility that I visited in Piscataway -- and lots of them. The quiet in the hallways, with the powerful computing servers tucked away behind closed doors, is a stark contrast to the busy, noisy construction activity taking place across the country. Those smaller data centers use less power and water, and they employ far fewer people -- and they're often hiding in plain sight.

[2]

AI Data Centers Are Massive, Energy-Hungry and Headed Your Way

From the outside, this nondescript building in Piscataway, New Jersey, looks like a standard corporate office surrounded by lookalike buildings. Even when I walk through the second set of double doors with a visitor badge slung around my neck, it still feels like I'll soon find cubicles, water coolers and light office chatter. Instead, it's one brightly lit server hall after another, each with slightly different characteristics, but all with one thing in common -- a constant humming of power. The first area I see has white tiled floors and rows of 7-foot-high server racks protected by black metal cages. Inside the cage structure, I feel cool air rushing from the floor toward the servers to prevent overheating. The wind muffles my tour guide's voice, and I have to shout over the noise for him to hear me. Outside the structure, it's quieter, but there's still a white noise that reminds me of the whooshing parents used to get newborn babies to sleep. On the back of the servers, I see hundreds of cords connected -- blue, red, black, yellow, orange, green. In a distant server, green lights are flashing. These machines, dozens of them, are gobbling electricity. In all, this building can support up to 3 megawatts of power. This is a data center. Facilities like it are increasingly common across the US, sheltering the machinery that makes our online lives not only possible, but nearly seamless. Data centers host our photos and videos, stream our Netflix shows, handle financial transactions, and so much more. The one I'm visiting, owned by a company called DataBank, is modest in scope. The ones coming in one after another to suburban communities and former farmlands across the US, riding the tidal wave of artificial intelligence's swift advances, are monstrous. It's a building boom based on generative AI. In late 2022, OpenAI launched ChatGPT, and within two months, it had approximately 100 million users and had spurred a frantic scramble among the biggest tech companies and a host of newborn startups. Now, it has nearly 700 million active users each week and 5 million paying business users. We are inundated with chatbots, image generators and speculation about superintelligence looming in the not-too-distant future. AI is being woven into our everyday lives, from banking and shopping to education and language learning. Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Apple and OpenAI are all spending massive amounts of money to drive that growth. The Trump administration has also made it clear that it wants the US to lead AI innovation across the globe. "We need to build and maintain vast AI infrastructure and the energy to power it," the White House said in July in a document called America's AI Action Plan, which calls for streamlined construction permitting and the removal of environmental regulations. "Simply put, we need to 'Build, Baby, Build!'" Building, and building big, is very much on the mind of Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg. He's been touting his company's plans for an AI data center in Louisiana, nicknamed Hyperion, that would be large enough to cover "a significant part of the footprint of Manhattan." All of that is adding up to an enormous demand for electricity and water to run and cool those new data centers. Generative AI requires energy-intensive training of large language models to do its impressive feats of computing. Meanwhile, a single ChatGPT query uses 10 times more energy than a standard Google search, and with millions of queries every day -- not just from ChatGPT but also from the likes of Google's Gemini, Microsoft's Copilot and Anthropic's Claude -- that's a staggering increase in the stresses on the US electrical grid and local water supplies. "Data centers are a critical part of the AI production process and to its deployment," said Ramayya Krishnan, professor of management science and information systems at Carnegie Mellon University's Heinz College. "Think of them as AI factories." But as data centers grow in both size and number, often drastically changing the landscape around them, questions are looming: What are the impacts on the neighborhoods and towns where they're being built? Do they help the local economy or put a dangerous strain on the electric grid and the environment? On the outskirts of communities across the country -- and sometimes smack dab in the middle of cities like New York -- giant AI data centers are springing up. Meta, for instance, is investing $10 billion into its 4-million-square-foot Hyperion data center, planned to open by 2030. An explosion of construction is likely coming to Pennsylvania. In July, at an energy summit in Pittsburgh attended by President Donald Trump, developers announced upward of $90 billion for AI in the state, including a $25 billion investment from Google. Perhaps the most ambitious undertaking is unfolding under the auspices of a new company called the Stargate Project, backed by OpenAI, Oracle, Softbank and others. In late January, on the day that Trump was sworn in to his second term as president, OpenAI said that Stargate would invest $500 billion in AI infrastructure over the next four years. An early signature facility for Stargate, amid reports of early struggles, is a sprawling data center under construction in Abilene, Texas. OpenAI said last month that Oracle had delivered the first Nvidia GB200 racks and that they were being used for "running early training and inference workloads." The publication R&D World has reported that the 875-acre site will eventually require 1.2GW of electricity, or the same amount it would take to power 750,000 homes. (Disclosure: Ziff Davis, CNET's parent company, in April filed a lawsuit against OpenAI, alleging it infringed Ziff Davis copyrights in training and operating its AI systems.) Currently, four tech giants -- Amazon Web Services, Google, Meta and Microsoft -- control 42% of the US data center capacity, according to BloombergNEF. The sky-high spending on AI data centers has become a major contributor to the US economy. Those four companies have spent nearly $100 billion in their most recent quarters on AI infrastructure, with Microsoft investing more than $80 billion into AI infrastructure during the current fiscal year alone. Not all data centers in the US handle AI workloads -- Google's data centers, for instance, power services including Google Cloud, Maps, Search and YouTube, along with AI -- but the ones that do can require more energy than small towns. A July report from the US Department of Energy said that AI data centers, in particular, are "a key driver of electricity demand growth." From 2021 to 2024, the number of data centers in the US nearly doubled, a PennEnvironment Research & Policy Center report found. And according to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the need for data centers is expected to increase by 9% each year until at least 2030. By 2035, data centers' US electricity demand is expected to double compared with today's. Here's another way to look at it: Speaking before the Senate Commerce Committee in May, Microsoft President Brad Smith said his company estimates that "over the next decade, the United States will need to recruit and train half a million new electricians to meet the country's growing electricity needs." As fast as the AI companies are moving, they want to be able to move even faster. Smith, in that Commerce Committee hearing, lamented that the US government needed to "streamline the federal permitting process to accelerate growth." This is exactly what's happening under the Trump administration. Its AI Action Plan acknowledges that the US needs to "build vastly greater energy generation" and lays out a path for getting there quickly. Among its recommendations are creating regulatory exclusions that favor data centers, fast-tracking permit approvals and reducing regulations under the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. One step already taken: The Trump administration rescinded a Biden administration executive order -- outlining the need to ensure AI development and use was done ethically and responsibly -- to reduce "onerous rules imposed." Early this year, June Ejk set up the Facebook page called Concerned Clifton Citizens to keep her neighbors informed about the happenings in Clifton Township, Pennsylvania. Now, her main focus is stopping a proposed 1.5GW data center campus from coming to the area that she's called home for the last 19 years. The developer, 1778 Rich Pike, is hoping to build a 34-building data center campus on 1,000 acres that spans both Clifton and Covington townships, according to Ejk and local reports. That 1,000 acres includes two watersheds, the Lehigh River and the Roaring Brook, Ejk says, adding that the developer's attorney has said each building would have its own well to supply the water needed. "Everybody in Clifton is on a well, so the concern was the drain of their water aquifers, because if there's that kind of demand for 34 more wells, you're going to drain everybody's wells," Ejk says. "And then what do they do?" Ejk, a retired school principal and former Clifton Township supervisor, says her top concerns regarding the data center campus include environmental factors, impacts on water quality or water depletion in the area, and negative effects on the residents who live there. Her fears are in line with what others who live near data centers have reported experiencing. According to a New York Times article in July, after construction kicked off on a Meta data center in Social Circle, Georgia, neighbors said wells began to dry up, disrupting their water source. The data center Ejk is hoping to stop hasn't yet been approved -- the developer has to get zoning ordinances amended and signed off on before moving forward -- but Covington Township has shown an interest in the project moving forward. For her part, Ejk has created and shared a "say no to a data center in our community" flyer with a call-to-action for her fellow citizens to attend monthly board of supervisors meetings for discussions on the topic. "I worry about the kind of world I'm leaving for my grandchildren," Ejk says. "It's not safer, it's not better, and we're selling out to these big corporations. You know, it's not in their backyard, it's in my backyard." If one or both of the townships do decide to move forward with the project, Ejk won't stop there. "I'm going to be telling residents to get your wells tested now, because if, after [the data centers] are built and the quality of your water changes, you will have to have a basis of what changed," she said. In Louisiana, some residents are welcoming Meta's planned data center in Richland Parish, the one that Zuckerberg says would cover a large part of Manhattan. Others, like Julie Richmond Sauer, believe it could harm the entire state. The facility will be located between the towns of Rayville, population of roughly 3,300, and Delhi, population 2,500. "It is 2,250 acres of farmland that will never be farmed again," Sauer, a registered nurse in central Louisiana, tells me. "That, of course, is a concern of mine, for my children and my grandchildren one day." She also thinks job development, a key selling point for data centers, is often overestimated. "It was sold by our legislators as, 'Hey, we're getting jobs,' which sounds wonderful. 'We're bringing industry in,' which sounds wonderful, but then the more I'm reading, it looks like 500 jobs max," Sauer says, who compared the amount with a medium-size hospital. The Louisiana Economic Development agency expects the data center to bring in 500 "direct jobs," or permanent ones, to the area, along with 1,000 "indirect" jobs and 5,000 construction and temporary jobs at its peak. It's unclear if those construction jobs would go to locals or to workers brought in temporarily from elsewhere. Meanwhile, OpenAI is pitching vastly more jobs for 4.5GW of Stargate data center capacity in the US, should it ever come to pass: 100,000 jobs, "spread across construction and operations roles." But it also acknowledges that the construction jobs would be "short-term." "I just don't think it's enough to sell your soul for," Sauer says. "They have only sold the positives in this and not told the public the negatives, and that's a fact." She believes ultimately that the decision on where to put these data centers should fall on a statewide public vote. There are currently more than 5,000 data centers in the US. While no state is completely free of these computing facilities, some states, such as Virginia, have become magnets for them. Ashburn, Virginia, alone boasts 140 data centers of the more than 500 in the state, earning the area the nickname "Data Center Alley." Texas and California, meanwhile, have more than 300 each. Virginia is attractive for data centers thanks to tax incentives, fiber optic infrastructure and a skilled workforce. Other states are actively trying to attract data centers by offering incentives, too. But concerns are rising regarding these tax breaks and who ends up picking up the bill. "More than 20 states are offering tax breaks to data centers in an effort to incentivize them to come to their state," Quentin Good, a policy analyst at Frontier Group, tells me. "So data centers are often given exemptions on things like the sales tax for all of the equipment that they need to fill up their data centers, and that ultimately falls on taxpayers to pay for the cost of those tax breaks." No matter where they're located, all data centers require a lot of power. According to the International Energy Agency, the US accounted for the largest share of global data center electricity consumption in 2024, at 45%. The Trump administration has emphasized the need to strengthen the grid to support the coming tidal wave of data centers. The president has gone so far as to declare the situation a national energy emergency. "The United States is experiencing an unprecedented surge in electricity demand driven by rapid technological advancements, including the expansion of artificial intelligence data centers and an increase in domestic manufacturing," an April executive order reads. To combat this issue, the government wants to use all available power sources, monitor the US electricity supply closely and follow the new AI Action Plan. "We've [previously] had really stable electricity demand increases of like 2% or 3%, but with a recent boom in data centers and the electrification of other things, like our homes and our vehicles, the [projected] demand for electricity is starting to jump up dramatically," Good says. Last month, a report from the Department of Energy warned that updates to the country's electric grid are imperative for grid reliability due to AI's escalating demands. "Absent intervention, it is impossible for the nation's bulk power system to meet the AI growth requirements while maintaining a reliable power grid and keeping energy costs low for our citizens," the report says. AI's growth and the need for more data centers to support it are rapidly increasing the stress on the US energy grid. This strain is causing "a lower system stability," the North American Electric Reliability Corporation's 2025 State of Reliability found. The US energy grid, built in the 1960s and '70s, was not designed to handle the energy pull AI is creating. At the end of 2023, the US energy grid -- which supports every request for electricity, from your home's lighting and air conditioning to massive industrial processes -- could handle about 1,189 gigawatts. Meta's Hyperion, for example, will have a capacity of 2 gigawatts, or 2,000 megawatts. That's a roughly 30 times greater demand for electricity than at DataBank's EWR2 location. "What we're seeing with new data centers is just the size difference," John Moura, NERC's director of reliability assessment and performance analysis, tells me. "For the past decade, we've probably seen a couple hundred megawatts as kind of your largest ones. Now we see interconnection requests for one or two or, I think I heard about 5-gigawatt requests, and that really changes the fundamentals of how the system is planned." The Alliance for Affordable Energy is challenging Meta's Louisiana data center -- calling it "a power-hungry giant" -- along with Entergy Louisiana's bid to build three gas plants to power it. Citing expert testimony, the group is sounding the alarm about a potentially debilitating strain on the electric grid and the cost to the citizens of Louisiana. "It's not exactly black and white in terms of who's paying for the [data center's] upgrades that are needed," Good says, adding that utilities have an obligation to serve all customers. "If any customer moves into their service area, they have to meet that customer's needs in terms of electricity." So, regardless of the scale of a data center, if they get approved to build in any town, the utility must provide the energy needed to power it. A large customer moving into the area could also cause a "short-term constraint on the supply of energy." "That's going to push utility prices up for everyone who's a customer of that utility," Good says. In a bid for additional energy sources, tech companies are turning to nuclear power as a possible solution, but Moura says nuclear power is still at least "a couple of years out." "In the next five years, there's not too many options to build generation, and so [energy] storage can help, but it's not a source of generation," Moura says. Meta has said it will begin using nuclear energy in 2027, with Amazon and Google hoping to use nuclear energy sometime in the 2030s. The water consumption of these data centers, specifically ones that help power AI, has been top of mind for many. Data centers use water to cool the servers. This usage is something that tech companies have tried -- and often failed -- to keep quiet. In 2022, after the newspaper The Oregonian sought records about Google's water use for a data center in The Dalles, the Oregon city sued to stop the paper from releasing the information. Eventually, the paper did receive the information, which revealed that in 2021, the Google data center used a staggering 355 million gallons of water, which is roughly equal to 538 Olympic-size swimming pools. The Oregonian's reporting helped shine a light on the natural resources these data centers need to run, and, maybe more importantly, it opened the question of whether our finite resources can handle the demand. According to Google's 2024 environmental report, the company's location that used the most water in 2023 was Council Bluffs, Iowa, home to two data centers, one built in 2007 and the other in 2012. In 2023, the Council Bluffs facilities sucked in 1.3 billion gallons of water from the local water supply. Google spent $1 billion in 2024 to expand the facility, and that year the intake rose to 1.4 billion gallons. Meta's 2024 sustainability report doesn't break down water usage by data center; it just gives an aggregate number. In 2023, its data centers worldwide took in 1.39 billion gallons of water. Just under 50% of that was permanently removed from local water sources. Between 2019 and 2023, Meta's data center water withdrawal increased by roughly 43%, but it still uses significantly less water than Google's data centers as a whole. When data centers consume water, a significant amount evaporates during the cooling process. The remaining water, which is often polluted, is put into the city's wastewater system. Both companies have stated they plan to be "water positive" by 2030, meaning they want to return more water to the communities than what the data centers consume through water recycling, reusing and water replenishment projects. However, returning water to the exact source the data center drew from is not always possible. Instead, Google states it attempts to improve additional water sources in the area, restore wetlands and recycle treated wastewater in an effort to counter its water usage. Even as big tech companies invest heavily in AI, they also continue to promote their sustainability goals. Amazon, for example, aims to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040. Google has the same goal but states it plans to reach it 10 years earlier, by 2030. With AI's rapid advancement, experts no longer know if those climate goals are attainable, and carbon emissions are still rising. "Wanting to grow your AI at that speed and at the same time meet your climate goals are not compatible," Good says. For its Louisiana data center, Meta has "pledged to match its electricity use with 100% clean and renewable energy" and plans to "restore more water than it consumes," the Louisiana Economic Development press release reads. However, questions remain around these promises. US Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island, the top Democrat on the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, questioned Meta and Zuckerberg in an official inquiry in May, labeling those climate pledges as "vague." Whitehouse said he believes Meta is putting the need for data centers and natural gas generation "over climate safety." Meta has not yet responded. Google's 2025 Environmental Report shows a 51% increase in carbon emissions in 2024 compared with 2019, despite its sustainability efforts outlined in the report. DataBank, although smaller in scale, also has a sustainability goal tied to its more than 65 locations. It plans to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2030. Jenny Gerson, DataBank's sustainability chief, tells me that DataBank has decreased emissions through "procuring renewable power on the grid" and is looking at alternative fuel sources to replace diesel fuel, including hydro-treated vegetable oil. "So instead of pulling more fossil fuels out of the ground and burning them, you're using a plant-based source that has a much shorter carbon cycle and leaving the fossil fuels in the ground," Gerson explains. DataBank is also prioritizing minimizing energy usage by switching to LED lightbulbs throughout its data centers, optimizing air flow to keep cool air around the servers and using closed-loop water systems, "meaning you fill the loop once, and then whatever water or glycol is in there remains in there, and you do not consume more water," she says. Microsoft is currently transitioning new data centers to closed-loop systems. Other possible solutions include creating flexible data centers, meaning they can pull less energy from the grid when energy usage in the surrounding community is expected to be high, such as during a heat wave or when severe weather is incoming. Both Meta and Google are founding members of the Electric Power Research Institute's DCFlex initiative, which aims to make more data centers flexible and help the energy grid remain reliable. "Obviously, everyone wants to use the internet, they want to use AI, and we need to do it responsibly," Gerson says. "So how can we as players do that? And a lot of that is making sure we're doing it through renewable power." There's at least one data center in each US state, and plenty more are on the horizon. If you don't live near one now, there's a good chance you will soon. If you live in an area that isn't prone to natural disasters and boasts natural resources, such as an abundance of water or robust wind, tech companies may be eyeing the spot for an AI factory. Google tells me it has "a very rigorous process to select sites, which includes factors like proximity to customers and users, local talent, land, a community that's excited to work with us and availability of (or potential to bring new) carbon-free energy." The Trump administration's AI Action Plan emphasizes the need for more data centers, electricians and HVAC technicians for the US to win the AI race. Many of the new data centers being built are massive and impossible to miss. There will be smaller ones as well, like Databank's EWR2 facility that I visited in Piscataway -- and lots of them. The quiet in the hallways, with the powerful computing servers tucked away behind closed doors, is a stark contrast to the busy, noisy construction activity taking place across the country. Those smaller data centers use less power and water, and they employ far fewer people -- and they're often hiding in plain sight.

[3]

AI data centers' soaring energy consumption is causing skyrocketing power bills for households across the US -- states reporting spikes in energy costs of up to 36%

Americans are footing the bill for the sheer amount of electricity required to operate the data centers responsible for providing access to AI tools and services. Tech companies are selling a vision of a world in which you can ask their AI for advice on what to cook, wear, and do with your free time. The quality of that advice is often dubious at best -- do you like putting glue on your pizza? -- but we're meant to believe this is the future of computing. As for who's paying for the massive amounts of electricity used in the course of answering those questions, well, the answer is "us" as consumer electricity prices across the country are already rising due to a power grid that's ill-prepared for the sudden spike in demand. Newsweek reports that increased consumption from data centers already contributed to a 6.5% increase in energy prices between May 2024 and May 2025. (Though it's worth noting that's just the average, with Connecticut and Maine reporting increases of 18.4% and 36.3%, respectively.) And those numbers are expected to rise as tech companies continue to build out their AI-related infrastructure. "To keep pace, utilities are increasingly relying on aging fossil fuel plants to generate enough electricity to meet the crushing demand," Newsweek says. "Dominion Energy, which serves much of Virginia, has asked regulators to require large-load customers to pay a fairer share of grid upgrade costs. Without reform, electricity prices in parts of Virginia are expected to climb as much as 25 percent by 2030." This problem is unlikely to be solved by developing more efficient models, either, and not just because software developers historically see improved efficiency as providing additional space to cram features into rather than a benefit unto itself. It's also because the AI tools available today rely upon the constant ingestion of information, which leads the companies that created them to fetch as much content as they possibly can. That incessant retrieval of the sum of digitally accessible human knowledge has other consequences -- which is why one scholar dubbed AI crawlers a "digital menace" -- but right now we're focused on the amount of energy those operations require. And constantly fetching all that information is merely the first step in the process of incorporating it into the AI's dataset. It's no wonder that Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory's 2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report (PDF) for the U.S. Department of Energy included a figure on data centers' electricity use that showed a "compound annual growth rate of approximately 7% from 2014 to 2018, increasing to 18% between 2018 and 2023, and then ranging from 13% to 27% between 2023 and 2028. That would lead to the industry's power usage representing "6.7% to 12.0% of total U.S. electricity consumption forecasted for 2028," according to the report. U.S. electric grids simply aren't prepared to meet those demands -- especially since they're also supposed to be preparing for "a combination of electric vehicle adoption, onshoring of manufacturing, hydrogen utilization, and the electrification of industry and buildings." It's not just a matter of unplugging these data centers, either, because their backup power supplies are a problem too. Reuters reports that "the rapid expansion of data centers processing the vast amounts of information used for AI and crypto mining is forcing grid operators to plan for new contingencies and complicating the already difficult task of balancing the country's supply and demand of electricity." That report cited several "near-misses" in which grid operators narrowly avoided wide-scale blackouts caused by data centers activating their own power generators, which can lead to an oversupply of electricity that can overwhelm the infrastructure they're connected to, unless the companies operating them respond quickly enough. Failing to do so could lead to "cascading power outages across the [affected] region." Even if that worst-case scenario is avoided, living near these power-hungry data centers reportedly "reduces the life span of electrical appliances, which can cause malfunctions, overheating, and electrical fires." (Which could in turn make this the first time a "not in my back yard" mentality is somewhat justified.) And that doesn't even consider the air, noise, and light pollution generated by these facilities. All of which is to say that the current obsession with AI is putting immense demands on electric grids, leading to additional stress on appliances connected to those grids, and increasing the risk of power outages through the use of on-site generators meant solely to protect the facility's equipment without regard for the effect it could have on everyone else -- and, per Newsweek's report, Americans are paying for that privilege.

[4]

This Asian data center hub is quietly grappling with the massive costs of AI: energy and water

But there are signs the industry is pushing the limits of the state's capacity and natural resources.The artificial intelligence boom has brought with it hundreds of billions of dollars in investments and promises of economic growth . But the infrastructure required is demanding massive amounts of energy and resources. One lesser-known example of that dilemma can be found in the southern tip of Malaysia, which has quietly become one of Southeast Asia's fastest-growing data center hubs amid the heightened compute demands of AI. The country's state of Johor -- with a population of about 4 million people -- has attracted billions' worth of projects for such data centers in recent years , including from many of the world's largest technology firms, such as Google , Microsoft and China's ByteDance . Backers of those projects have been drawn by Johor's cheap land and resources, proximity to the financial hub of Singapore, and government incentives. But though that has created new economic opportunities and jobs, there are signs the industry is pushing the limits of the state's energy capacity and natural resources, with officials slowing approvals for new projects. Energy needs and hurdles While Johor currently has about 580 megawatts (MW) of data center capacity, its total planned capacity -- including early-stage projects -- is nearly 10 times that amount, according to figures provided by data center market intelligence firm DC Byte. That energy capacity would be enough to power up to 5.7 million households an hour , according to calculations based on data from PKnergy . Meanwhile, though Johor accounts for the majority of Malaysia's planned data centers, other hubs in the country have been sprouting up. Kenanga Investment Bank Berhad, a Malaysian independent investment bank, has projected that the electricity use of the country's data centers will equate to 20% of its total energy-generating capacity by 2035. In the face of those growing demands, a Malaysian industry official told reporters in June that the country expects to add 6 to 8 gigawatts of gas-fired power, with total power consumption on track to increase 30% by 2030. Though the natural gas used in these power stations burns cleaner than coal -- which accounted for more than 43% of Malaysia's electricity in 2023 -- reliance on it for future data center expansion could clash with the country's plan to achieve net-zero emissions as early as 2050. Another critical challenge is water, which is used by data centers in large quantities to cool down electrical components and prevent overheating. It's been estimated that an average 100 MW data center uses about 4.2 million liters of water per day -- the equivalent of supplying thousands of residents . It's therefore no surprise that Johor, which has experienced several supply disruptions and already relies on neighboring Singapore for a sizeable amount of its treated water, is reportedly in the process of building three new reservoirs and water treatment plants. Global picture Data centers are the backbone of the digital world, hosting the information and computing resources that power everything from e-commerce to social media to digital banking, and increasingly, generative AI models. Demand and investor appetite for such centers have never been higher, given the massive computing power needs of AI , with Johor serving as just one example of the industry's growth and the energy and water challenges that come with it. According to a May report by the International Monetary Fund, electricity used by the world's data centers had already reached the levels of Germany and France in 2023, soon after the launch of OpenAI's groundbreaking ChatGPT AI model. Meanwhile, some researchers have estimated that AI-related infrastructure could consume four to six times more water than Denmark by 2027. The industry's growth is expected to continue to accelerate, though projections of future capacity vary widely. One thing that is clear is that data center construction is struggling to keep up with demand in light of power constraints and permitting delays, according to DC Byte. In response, some governments have been working to speed up approval processes and bring new and cheap energy online, with some environmentalists warning such moves could clash with global net-zero goals. The United States -- the world's largest data center market -- has exemplified that dynamic. U.S. President Donald Trump recently launched " America's AI Action Plan ," calling for streamlined permitting and the removal of environmental regulations to speed up the development of AI infrastructure and the energy needed to power it. A June analysis from Carnegie Mellon University and North Carolina State University projected that by 2030, Americans' electricity bills are on track to rise 8% and greenhouse gas emissions from power generation 30% as a result of growth in data centers and cryptocurrency mining. Resource solutions? Malaysia, for its part, has signaled its desire to rein in the data center industry's energy and resource use. The government plans to launch a "Sustainable Data Centre Framework" by October, Tengku Zafrul, investment, trade and industry minister, said in a post on X in July. To meet growing power needs, officials have also been approving more renewable energy projects , while also exploring the potential use of nuclear energy . As for water, higher water tariffs were placed on Johor's data centers earlier this month, with the government pushing for the industry to shift to using recycled wastewater . Notably, some newer data centers don't rely on any water for cooling. Regionally, concerns about resource-intensive data centers are nothing new. In 2019, Singapore cracked down on the industry, imposing a three-year moratorium on new data centers in order to stem power and water usage. It was after that crackdown that the industry began its major shift to the friendlier regulatory environment of Johor. Singapore ended its moratorium in 2022 and launched its "Green Data Centre Roadmap ," aimed at optimizing energy efficiency and adopting green energy for data centers. However, according to data from DC Byte, growth in the city-state remains tempered , especially when compared with Malaysia. Stricter approaches could, however, lead to spillover to less-regulated markets. As few international guardrails are in place, environmentalists and organizations like the United Nations Environment Programme have been calling for global legislation. "There are no unavoidable AI uses, and whether we move towards net-zero emissions is a choice," Jonathan Koomey , a leading independent researcher on the energy and environmental effects of information technology, told CNBC in an email. "There is no reason, in my view, why data center companies shouldn't power AI expansion with zero emissions power. There is also no reason to abandon climate goals because AI companies say their expansion is urgent."

[5]

Trump's AI plan calls for massive data centers. Here's how it may affect energy in the US

President Donald Trump's plan to boost artificial intelligence and build data centers across the U.S. could speed up a building boom that was already expected to strain the nation's ability to power it. The White House released the "AI Action Plan" Wednesday, vowing to expedite permitting for construction of energy-intensive data centers as it looks to make the country a leader in a business that tech companies and others are pouring billions of dollars into. The plan says to combat "radical climate dogma," a number of restrictions -- including clean air and water laws -- could be lifted, aligning with Trump's "American energy dominance" agenda and his efforts to undercut clean energy. Here's what you need to know. Massive amounts of electricity are needed to support the complex servers, equipment and more for AI. Electricity demand from data centers worldwide is set to more than double by 2030, to slightly more than the entire electricity consumption of Japan today, the International Energy Agency said earlier this year. In many cases, that electricity may come from burning coal or natural gas. These fossil fuels emit planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions, including carbon dioxide and methane. This in turn is tied to extreme weather events that are becoming more severe, frequent and costly. The data centers used to fuel AI also need a tremendous amount of water to keep cool. That means they can strain water sources in areas that may have little to spare. Typically, tech giants, up-and-comers and other developers try to keep an existing power plant online to meet demand, experts say, and most existing power plants in the U.S. are still producing electricity using fossil fuels -- most often natural gas. In certain areas of the U.S., a combination of renewables and energy storage in the form of batteries are coming online. But tapping into nuclear power is especially of interest as a way to reduce data center-induced emissions while still meeting demand and staying competitive. Amazon said last month it would spend $20 billion on data center sites in Pennsylvania, including one alongside a nuclear power plant. The investment allows Amazon to plug right into the plant, a scrutinized but faster approach for the company's development timeline. Meta recently signed a deal to secure nuclear power to meet its computing needs. Microsoft plans to buy energy from the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant, and Google previously signed a contract to purchase it from multiple small modular reactors in the works. Data centers are often built where electricity is cheapest, and often, that's not from renewables. And sometimes data centers are cited as a reason to extend the lives of traditional, fossil-fuel-burning power plants. But just this week, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres called on the world's largest tech players to fuel their data center needs entirely with renewables by 2030. It's necessary to use fewer fossil fuels, he said. Experts say it's possible for developers, investors and the tech industry to decarbonize. However, though industry can do a lot with clean energy, the emerging demands are so big that it can't be clean energy alone, said University of Pennsylvania engineering professor Benjamin Lee. More generative AI, ChatGPT and massive data centers means "relying on wind and solar alone with batteries becomes really, really expensive," Lee added, hence the attention on natural gas, but also nuclear. Regardless of what powers AI, the simple law of supply and demand makes it all but certain that costs for consumers will rise. New data center projects might require both new energy generation and existing generation. Developers might also invest in batteries or other infrastructure like transmission lines. All of this costs money, and it needs to be paid for from somewhere. "In a lot of places in the U.S., they are seeing that rates are going up because utilities are making these moves to try to plan," said Amanda Smith, a senior scientist at research organization Project Drawdown. "They're planning transmission infrastructure, new power plants for the growth and the load that's projected, which is what we want them to do," she added. "But we as ratepayers will wind up seeing rates go up to cover that." Read more of AP's climate coverage at http://www.apnews.com/climate-and-environment ___ The Associated Press' climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP's standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

[6]

Data centers use massive energy and water. Here's how to build them better

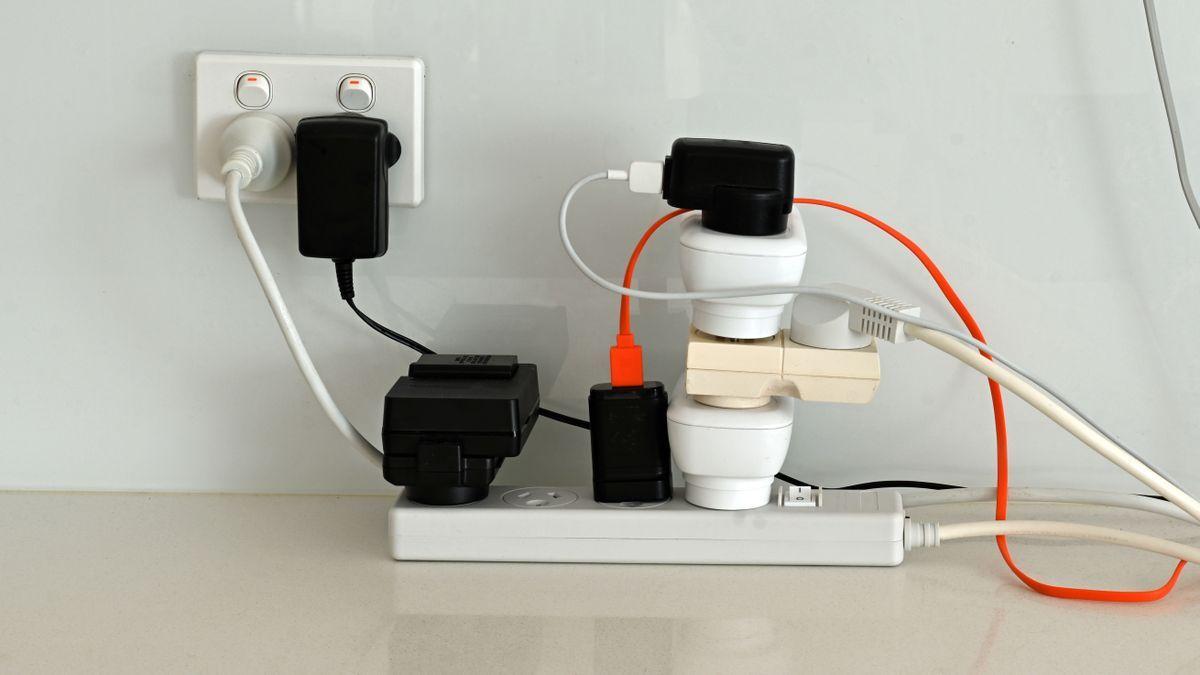

In late July, the Trump administration released its long-awaited AI Action Plan, which includes steps to cut environmental requirements and streamline permitting policies to make it easier to build data centers and power infrastructure. But even with massive deregulation, the fact remains: we have no idea where we'll find all the energy, water, and grid capacity to meet the enormous speed and scale of the emerging AI revolution. Recently, experts from the International Energy Agency estimated that electricity use from data centers could more than double in the next five years. By 2030, these facilities could use nearly 9% of all electricity in the United States. Without major investments, this growth will strain our power grid and lead to higher energy bills for everyone. And it's not just energy. Globally, by 2027, water consumption from AI alone is estimated to reach the equivalent of more than half the annual water usage of the U.K. Researchers at the University of California, Riverside, estimate that a ChatGPT user session that involves a series of between 5 and 50 prompts or questions can consume up to 500 milliliters of water (about the amount in a 16-ounce bottle). Google used a fifth more water in 2022 compared to 2021 as it ramped up its artificial intelligence work. Microsoft's water usage increased by 34% over the same period. On top of all this, many communities are protesting or rejecting data center construction due to factors like noise disturbances and limited job-creation benefits.

[7]

AI Is Changing the Way We Live and Work. But It Comes With Very Real Human Risks.

There's a reason there's so much hype over generative artificial intelligence. It can summarize and synthesize massive amounts of data, test results of different strategies and actions, generate code, create apps and even brainstorm ideas. But as someone who studies the social, ethical and environmental responsibilities of businesses, I believe we need to be clear-eyed about the costs associated with this new technology, even as it has already begun to transform our workplaces, our daily lives, the economy and even society itself. Open AI founder and CEO Sam Altman recently made headlines when he confirmed that saying "please" and "thank you" in your ChatGPT queries probably costs his company "tens of millions of dollars" in additional electricity costs, joking that it was probably money "well spent - you never know." The truth is that even without adding polite niceties to conversations with our potential future robot overlords, asking ChatGPT a question uses 10 times more energy than running a standard Google search without AI overviews summarizing results, according to a May 2024 report by the Electric Power Research Institute. With artificial intelligence use booming, global energy demand for data servers is expected to triple over the next decade, according to the International Energy Agency. In the U.S. alone, data centers are expected to use as much as 20% of all electricity used by 2032, up from 3.5% today, according to research by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. In Texas alone, the United States' second largest data center market by energy consumption, the annual energy capacity that will need for data centers by 2031 is projected to nearly equal the capacity needed for the state's current peak electricity demand in the scorching summer months, according to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas. AI companies responsible for all this energy use are weaving clever narratives to quiet questions and concerns about how the power grid - and the world - are going to keep up with the pace of AI expansion, arguing that AI itself will become increasingly efficient and will create knock-on efficiencies that benefit the entire economy. But do those stories really hold up? I have my doubts. Google, for example, continues to set an ambitious goal of getting to net zero carbon emissions by 2030 even as AI data center build-outs scuttle current carbon neutrality claims. The company claims that gains in efficiency of AI architecture, in part through the application of AI, will help mitigate the increase in energy use across its supply chain. But given the longevity of energy infrastructure (for example, new gas-powered plants being built for Meta that will last for decades), this claim is dubious at best. Professional services giant PwC, in partnership with Microsoft, echoes Google's assertion that AI may even innovate dramatic energy efficiencies, allowing its use to offset the energy demand it requires. But an economics concept known as Jevons paradox that dates back to the coal-power era suggests that technological advancements that make resource use more efficient can paradoxically lead to increased overall consumption of that same resource. Moreover, reducing future emissions does nothing to help draw down atmospheric carbon being released in building out today's AI infrastructure. On top of its voracious use of energy, AI may also come at a massive social cost in lost employment and diminished human cognitive abilities. The World Economic Forum predicts that some 92 million jobs will be lost to AI even as it creates 170 million new roles in the coming years - a major labor displacement. The nonprofit AI Futures Project predicts that by 2027, not only will AI displace millions of jobs - including many of those involved with building the AI itself - but it will also radically transform how we as humans manage ourselves, as we outsource our individual and collective decision-making to AI. In her recent book "Empire of AI," journalist Karen Hao exposes the fundamental tensions between OpenAI's business imperatives to scale and its original mission to ensure that AI serves humanity's interests. Hao highlights several issues that AI-forward companies need to confront, including the desire for secrecy to protect intellectual property versus the need for transparency and accountability and the need to balance the insatiable use of resources with ethical responsibility. Hao suggests that commercial interests are drowning out ethical concerns. So where does this leave us? The lid of the AI Pandora's box is fully off its hinges, and there is no turning back. But we must demand transparency and accountability from AI companies rather than allowing them to pretend that these innovations come at no cost. We must push for government and corporate policies that ensure the massive AI industrial complex is tied to the development of clean energy infrastructure. Building cheap gas plants fast and worrying about decarbonization later is not a viable option. Maybe AI itself can play a helpful role in designing the solutions to the very environmental problems it's creating. But it's time to ditch the ludicrous notion that AI and the people who create it will solve the problems they create without meaningful human oversight.

Share

Share

Copy Link

The rapid growth of AI data centers is causing significant strain on U.S. energy grids and resources, leading to increased electricity costs and environmental concerns.

The Rise of AI Data Centers

The artificial intelligence boom has sparked a massive expansion of data centers across the United States. These facilities, described as "AI factories" by Ramayya Krishnan of Carnegie Mellon University, are the backbone of our digital world and the driving force behind AI advancements

1

2

. Major tech companies like Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI are investing billions in these infrastructures to support the growing demand for AI services1

2

.

Source: CNET

Energy and Resource Demands

The scale of energy consumption by these data centers is staggering. A single ChatGPT query uses ten times more energy than a standard Google search, and with millions of queries daily, the strain on the US electrical grid is significant

1

2

. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory projects that by 2028, data centers could consume between 6.7% to 12.0% of total U.S. electricity3

.

Source: Tom's Hardware

Water usage is another critical concern. An average 100 MW data center uses about 4 million liters of water daily for cooling purposes

4

. This massive water consumption is putting pressure on local water supplies, particularly in areas already facing scarcity.Economic and Environmental Impact

The rapid growth of AI data centers is having far-reaching effects:

-

Rising Energy Costs: Newsweek reports that increased consumption from data centers contributed to a 6.5% increase in energy prices between May 2024 and May 2025, with some states seeing spikes of up to 36.3%

3

. -

Grid Stability Concerns: The backup power supplies of these data centers pose risks to grid stability, potentially leading to cascading power outages if not managed properly

3

. -

Environmental Challenges: The reliance on fossil fuels to meet the growing energy demands clashes with net-zero emission goals. In Malaysia, for example, the electricity use of data centers is projected to equate to 20% of the country's total energy-generating capacity by 2035

4

.

Related Stories

Policy and Industry Response

The Trump administration has launched "America's AI Action Plan," calling for streamlined permitting and the removal of environmental regulations to accelerate AI infrastructure development

5

. This approach, however, has raised concerns among environmentalists about potential conflicts with global net-zero goals.In response to these challenges, some initiatives are being explored:

-

Sustainable Practices: Malaysia plans to launch a "Sustainable Data Centre Framework" and is pushing for the industry to shift to using recycled wastewater

4

. -

Alternative Energy Sources: Tech giants are increasingly looking at nuclear power as a potential solution. Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and Google have all made moves to secure nuclear power for their data centers

5

.

Source: AP

- Renewable Energy: There's a growing call for data centers to be powered entirely by renewables by 2030, as advocated by UN Secretary-General António Guterres

5

.

Future Outlook

As the AI industry continues to grow, the balance between technological advancement and environmental sustainability remains a critical challenge. The massive energy and resource demands of AI data centers are reshaping America's infrastructure and energy landscape, necessitating innovative solutions and careful policy considerations to ensure sustainable growth in this rapidly evolving sector.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[4]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Pentagon's Anthropic showdown exposes who controls AI guardrails in military contracts

Policy and Regulation

3

Anthropic challenges Pentagon supply chain risk label in court over AI usage restrictions

Policy and Regulation