University of Illinois Students Caught Using AI to Apologize for Cheating, Highlighting Academic Integrity Crisis

5 Sources

5 Sources

[1]

When caught cheating in college, don't apologize with AI

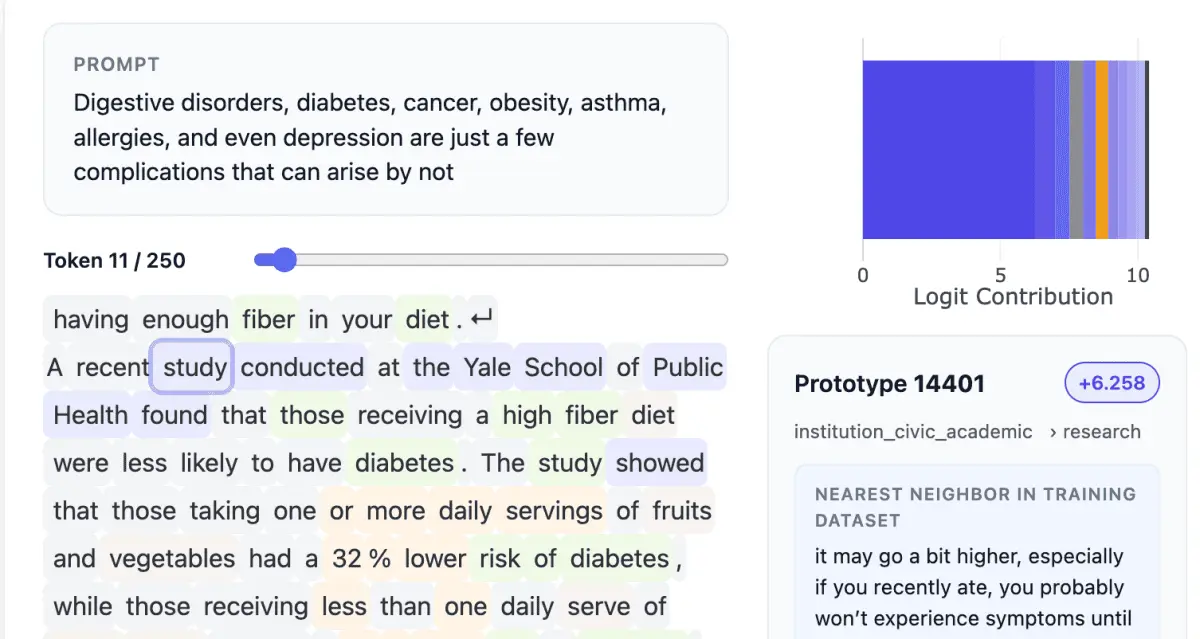

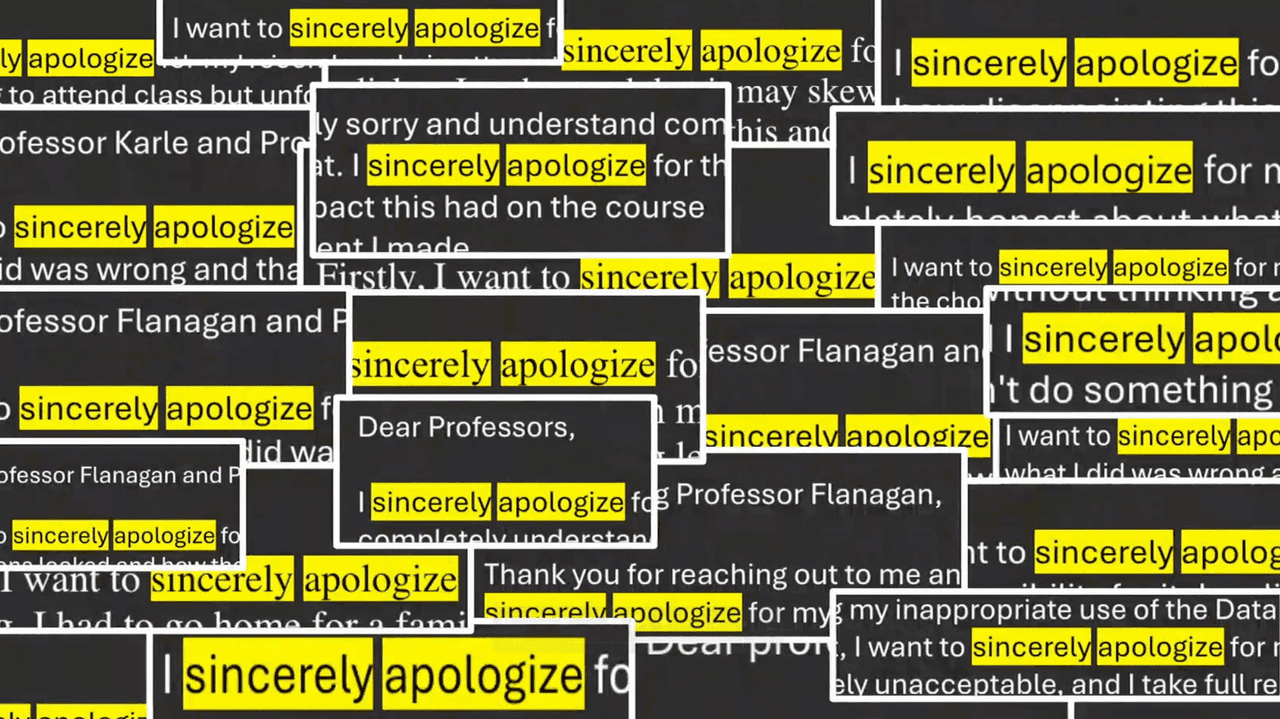

With a child in college and a spouse who's a professor, I have front-row access to the unfolding debacle that is "higher education in the age of AI." These days, students routinely submit even "personal reflection" papers that are AI generated. (And routinely appear surprised when caught.) Read a paper longer than 10 pages? Not likely -- even at elite schools. Toss that sucker into an AI tool and read a quick summary instead. It's more efficient! So the University of Illinois story that has been running around social media for the last week (and which then bubbled up into The New York Times yesterday) caught my attention as an almost perfect encapsulation of the current higher ed experience... and how frustrating it can be for everyone involved. Data Science Discovery is an introductory course taught by statistics prof Karle Flanagan and the gloriously named computer scientist Wade Fagen-Ulmschneider, whose website features a logo that says, "Keep Nerding Out." Attendance and participation counts for a small portion of the course grade, and the profs track this with a tool called the Data Science Clicker. Students attending class each day are shown a QR code, which after being scanned takes them to a multiple-choice question that appears to vary by person. They have a limited time window to answer the question -- around 90 seconds. A few weeks into this fall semester, the professors realized that far more students were answering the questions -- and thus claiming to be "present" -- than were actually in the lecture hall. (The course has more than 1,000 students in it, across multiple sections.) According to the Times, "The teachers said they started checking how many times students refreshed the site and the IP addresses of their devices, and began reviewing server logs." Students were apparently being told by people from the class when the questions were going live. When the profs realized how widespread this was, they contacted the 100-ish students who seemed to be cheating. "We reached out to them with a warning, and asked them, 'Please explain what you just did,'" said Fagen-Ulmschneider in an Instagram video discussing the situation. Apologies came back from the students, first in a trickle, then in a flood. The profs were initially moved by this acceptance of responsibility and contrition... until they realized that 80 percent of the apologies were almost identically worded and appeared to be generated by AI. So on October 17, during class, Flanagan and Fagen-Ulmschneider took their class to task, displaying a mash-up image of the apologies, each bearing the same "sincerely apologize" phrase. No disciplinary action was taken against the students, and the whole situation was treated rather lightly -- but the warning was real. Stop doing this. Flanagan said that she hoped it would be a "life lesson" for the students. On a University of Illinois subreddit, students shared their own experiences of the same class and of AI use on campus. One student claimed to be a teaching assistant for the Data Science Discovery course and claimed that, in addition to not being present, many students would use AI to solve the (relatively easy) problems. AI tools will often "use functions that weren't taught in class," which gave the game away pretty easily. Another TA claimed that "it's insane how pervasive AI slop is in 75% of the turned-in work," while another student complained about being a course assistant where "students would have a 75-word paragraph due every week and it was all AI generated." One doesn't have to read far in these kinds of threads to find plenty of students who feel aggrieved because they were accused of AI use -- but hadn't done it. Given how poor most AI detection tools are, this is plenty plausible; and if AI detectors aren't used, accusations often come down to a hunch. Everyone appears to be unhappy with the status quo. AI can be an amazing tool that can assist with coding, web searches, data mining, and textual summation -- but I'm old enough to wonder just what the heck you're doing at college if you don't want to process arguments on your own (ie, think and read critically) or even to write your own "personal reflections" (ie, organize and express your deepest thoughts, memories, and feelings). Outsource these tasks often enough and you will fail to develop them. I recently wrote a book on Friedrich Nietzsche and how his madcap, aphoristic, abrasive, humorous, and provocative philosophizing can help us think better and live better in a technological age. The idea of simply reading AI "summaries" of his work -- useful though this may be for some purposes -- makes me sad, as the desiccated summation style of ChatGPT isn't remotely the same as encountering a novel and complex human mind expressing itself wildly in thought and writing. And that's assuming ChatGPT hasn't hallucinated anything. So good luck, students and professors both. I trust we will eventually muddle our way through the current moment. Those who want an education only for its "credentials" -- not a new phenomenon -- have never had an easier time of it, and they will head off into the world to vibe code their way through life. More power to them. But those who value both thought and expression will see the AI "easy button" for the false promise that it is and will continue to do the hard work of engaging with ideas, including their own, in a way that no computer can do for them.

[2]

Tech companies don't care that students use their AI agents to cheat

AI companies know that children are the future -- of their business model. The industry doesn't hide their attempts to hook the youth on their products through well-timed promotional offers, discounts, and referral programs. "Here to help you through finals," OpenAI said during a giveaway of ChatGPT Plus to college students. Students get free yearlong access to Google's and Perplexity's pricey AI products. Perplexity even pays referrers $20 for each US student that it gets to download its AI browser Comet. Popularity of AI tools among teens is astronomical. Once the product makes its way through the education system, it's the teachers and students who are stuck with the repercussions; teachers struggle to keep up with new ways their students are gaming the system, and their students are at risk of not learning how to learn at all, educators warn. This has gotten even more automated with the newest AI technology, AI agents, which can complete online tasks for you. (Albeit slowly, as The Verge has seen in tests of several agents on the market.) These tools are making things worse by making it easier to cheat. Meanwhile tech companies play hot potato with the responsibility for how their tools can be used, often just blaming the students they've empowered with a seemingly unstoppable cheating machine. Perplexity actually appears to lean into its reputation as a cheating tool. It released a Facebook ad in early October that showed a "student" discussing how his "peers" use Comet's AI agent to do their multiple-choice homework. In another ad posted the same day to the company's Instagram page, an actor tells students that the browser can take quizzes on their behalf. "But I'm not the one telling you this," she says. When a video of Perplexity's agent completing someone's online homework -- the exact use case in the company's ads -- appeared on X, Perplexity CEO Aravind Srinivas reposted the video, quipping, "Absolutely don't do this." When The Verge asked for a response to concerns that Perplexity's AI agents were used to cheat, spokesperson Beejoli Shah said that "every learning tool since the abacus has been used for cheating. What generations of wise people have known since then is cheaters in school ultimately only cheat themselves." This fall, shortly after the AI industry's agentic summer, educators began posting videos of these AI agents seamlessly filing assignments in their online classrooms: OpenAI's ChatGPT agent generating and submitting an essay on Canvas, one of the popular learning management dashboards; Perplexity's AI assistant successfully completing a quiz and generating a short essay. In another video, ChatGPT's agent pretends to be a student on an assignment meant to help classmates get to know each other. "It actually introduced itself as me ... so that kind of blew my mind," the video's creator, college instructional designer Yun Moh, told The Verge. Canvas is the flagship product of parent company Instructure, which claims to have tens of millions of users, including those at "every Ivy League school" and "40% of U.S. K-12 districts." Moh wanted the company to block AI agents from pretending to be students. He asked Instructure in its community ideas forum and sent an email to a company sales rep, citing concerns of "potential abuse by students." He included the video of the agent doing Moh's fake homework for him. It took nearly a month for Moh to hear from Instructure's executive team. On the topic of blocking AI agents from their platform, they seemed to suggest that this was not a problem with a technical solution, but a philosophical one, and in any case, it should not stand in the way of progress: "We believe that instead of simply blocking AI altogether, we want to create new pedagogically-sound ways to use the technology that actually prevent cheating and create greater transparency in how students are using it. "So, while we will always support work to prevent cheating and protect academic integrity, like that of our partners in browser lockdown, proctoring, and cheating-detection, we will not shy away from building powerful, transformative tools that can unlock new ways of teaching and learning. The future of education is too important to be stalled by the fear of misuse." Instructure was more direct with The Verge: Though the company has some guardrails verifying certain third-party access, Instructure says it can't block external AI agents and their unauthorized use. Instructure "will never be able to completely disallow AI agents," and it cannot control "tools running locally on a student's device," spokesperson Brian Watkins said, clarifying that the issue of students cheating is, at least in part, technological. Moh's team struggled as well. IT professionals tried to find ways to detect and block agentic behaviors like submitting multiple assignments and quizzes very quickly, but AI agents can change their behavioral patterns, making them "extremely elusive to identify," Moh told The Verge. In September, two months after Instructure inked a deal with OpenAI, and one month after Moh's request, Instructure sided against a different AI tool that educators said helped students cheat, as The Washington Post reported. Google's "homework help" button in Chrome made it easier to run an image search of any part of whatever is on the browser -- such as a quiz question on Canvas, as one math teacher showed -- through Google Lens. Educators raised the alarm on Instructure's community forum. Google listened, according to a response on the forum from Instructure's community team, and an example of the two companies' "long-standing partnership" that includes "regular discussions" about education technology, Watkins told The Verge. When asked, Google maintained that the "homework help" button was just a test of a shortcut to Lens, a preexisting feature. "Students have told us they value tools that help them learn and understand things visually, so we have been running tests offering an easier way to access Lens while browsing," Google spokesperson Craig Ewer told The Verge. The company paused the shortcut test to incorporate early user feedback. Google leaves open the possibility of future Lens/Chrome shortcuts, which it's hard to imagine won't be marketed to students given the presence of a recent company blog, written by an intern, declaring: "Google Lens in Chrome is a lifesaver for school." Some educators found that agents would occasionally, but inconsistently, refuse to complete academic assignments. But that guardrail was easy to overcome, as college English instructor Anna Mills showed by instructing OpenAI's Atlas browser to submit assignments without asking for permission. "It's the wild west," Mills said to The Verge about AI use in higher education. This is why educators like Moh and Mills want AI companies to take responsibility for their products, not blame students for using them. The Modern Language Association's AI task force, which Mills sits on, released a statement in October calling on companies to give educators control over how AI agents and other tools are used in their classrooms. OpenAI appears to want to distance itself from cheating while maintaining a future of AI-powered education. In July, the company added a study mode to ChatGPT that does not provide answers, and OpenAI's vice president of education, Leah Belsky, told Business Insider that AI should not be used as an "answer machine." Belsky told The Verge: "Education's role has always been to prepare young people to thrive in the world they'll inherit. That world now includes powerful AI that will shape how work gets done, what skills matter, and what opportunities are available. Our shared responsibility as an education ecosystem is to help students use these tools well -- to enhance learning, not subvert it -- and to reimagine how teaching, learning, and assessment work in a world with AI." Meanwhile, Instructure leans away from trying to "police the tools," Watkins emphasized. Instead, the company claims to be working toward a mission to "redefine the learning experience itself." Presumably, that vision does not include constant cheating, but their proposed solution rings similar to OpenAI's: "a collaborative effort" between the companies creating the AI tools and the institutions using them, as well as teachers and students, to "define what responsible AI use looks like." That is a work in progress. Ultimately, the enforcement of whatever guidelines for ethical AI use they eventually come up with on panels, in think tanks, and in corporate boardrooms will fall on the teachers in their classrooms. Products have been released and deals have been signed before those guidelines have even been established. Apparently, there's no going back.

[3]

Their Professors Caught Them Cheating. They Used A.I. to Apologize.

Confronted with allegations that they had cheated in an introductory data science course and fudged their attendance, dozens of undergraduates at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign recently sent two professors a mea culpa via email. But there was one problem, a glaring one: They had not written the emails. Artificial intelligence had, according to the professors, Karle Flanagan and Wade Fagen-Ulmschneider, an academic pair known to their students and social media followers as the Data Science Duo. The students got their comeuppance in a large lecture hall on Oct. 17, when the professors read aloud their identical, less-than-genuine apologies from a projector screen, video from that class showed. Busted. The professors posted about it on social media, where the gotcha moment drew widespread attention. "They said, 'Dear Professor Flanagan, I want to sincerely apologize,'" Professor Flanagan said. "And I was like, Thank you. They're owning up to it. They're apologizing. And then I got another email, the second email, and then the third. And then everybody sort of sincerely apologizing, and suddenly it became a little less sincere." At a time when educational institutions are grappling with the intrusion of machine learning into classrooms and homework assignments, the professors said they decided to use the episode to teach a lesson in academic integrity. They did not take disciplinary action against the students. "You can hear the students laugh in the background of the video," Professor Fagen-Ulmschneider said. "They knew that it was something that they could see themselves doing." It was not clear if the University of Illinois would punish the students who were involved. The university did not immediately respond to a request for comment on Wednesday. Although the university's student code covers cheating and plagiarism, the professors said that they were not aware of specific rules applying to the use of A.I. About 1,200 students take the course, which is divided into two sections that meet on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Attendance and participation in the lectures count for 4 percent of the final grade in the class, which is primarily taken by first-year students. To track the engagement of the class, the professors created an application known as the Data Science Clicker that requires students to log in on their phones or computers and, when prompted by a QR code, answer a multiple-choice question in certain amount of time, usually about 90 seconds. But in early October, the professors said they began to grow suspicious when dozens of students who were absent from class were still answering the questions. So the teachers said they started checking how many times students refreshed the site and the IP addresses of their devices, and began reviewing server logs. "Sometimes on Fridays, some students will go up to Chicago," said Professor Fagen-Ulmschneider, 40, a teaching professor in the Siebel School of Computing and Data Science. It appeared that the students had been tipped off about the questions and when they had to respond, according to the professors, who sent emails to more than 100 students telling them that the ruse was up. "We take academic integrity very seriously here, so we wanted to make sure to give them a warning," said Professor Flanagan, 36, a teaching associate professor in the Department of Statistics. Alex Von Holten, 20, a sophomore who took the class in the spring semester this year, said he wasn't surprised to learn that some students had been "sleepwalking" through it. The format, a large lecture with introductory material, might lead some people to slack off, he said. "It's really hard not to get an A in that class," Mr. Von Holten said. To do worse, he added, "you have to genuinely just not show up and not care." Vinayak Bagdi, 21, who graduated in May with a degree in statistics, took the class as a freshman to fulfill his academic requirements. Four years later, he said, the professors' dedication to demystifying statistics had stuck with him. He said he never felt bombarded with information or too lost to keep up with assignments in the class, and he described the professors as being heavily invested in the success of students. That made it especially disheartening that some students had used A.I., Mr. Bagdi said. "You're not even coming to the class, and then you can't even send a sincere email to the professor saying, 'I apologize'?" he said. "Out of any class at the university, why skip that one?"

[4]

Professors Aghast as Class Caught Cheating "Sincerely" Apologizes in the Worst Possible Way

If you get caught cheating by your professor, you would be wise to beg for mercy, grovel at their feet, and pour every ounce of your soul into putting on the contrite performance of a lifetime. You'll never do it again, you vow, after reminding them of your recently deceased distant relative. If there was ever a moment to put some real effort into your education, this big apology would be it. In an age of ChatGPT, however, even that might be a lot to ask. After catching dozens of their students cheating in a data science course, two professors at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign were inundated with what they thought were nearly a hundred heartfelt emails from the students apologizing for their mistakes. But you probably see where this is going. The overwhelming majority of those emails, the professors noticed, appeared to themselves be written by an AI chatbot. The duo, Karle Flanagan and Wade Fagen-Ulmschneider, confronted their students about it in class, projecting their similarly worded apologies on screen. The phrase "sincerely apologize" is highlighted in all of the dozens of examples. "They said, 'Dear Professor Flanagan, I want to sincerely apologize,'" Flanagan told the New York Times. "And I was like, Thank you. They're owning up to it. They're apologizing." "And then I got another email, the second email, and then the third," Flanagan added. "And then everybody sort of sincerely apologizing, and suddenly it became a little less sincere." It's the latest stupefying example of how AI has irreversibly transformed education, and undoubtedly for the worse. It's not just the tech's effortless automation that's so alarming, robbing students of the challenge of actually having to use their brain to think through a problem; its very existence has fostered a climate of distrust, where the relationship between pupil and professor is clouded by suspicion and resentment. The professor must constantly be suspicious of a student using AI to cheat. And the student resents being subjected to this scrutiny, sometimes unfairly. Many have been wrongly accused of using AI -- accusations that themselves are sometimes made with AI tools. Flanagan and Fagen-Ulmschneider said they were on the lookout for cheating after they noticed that students who skipped class were still answering time-sensitive questions that were designed to only be accessed through an app while physically in attendance to scan a QR code, they told the NYT. Answering these went to their participation grade. After some digging, the professors realized that the truants were getting tipped off by their peers about when to answer the questions. Their confrontation with the students about the "sincere" apologies went mega-viral on Reddit, after a student posted a photo of the scene. Going viral, though, wasn't the professors intent. "We were ready to move past it but then we woke up the next day and it was on the front page of Twitter and Reddit!" Flanagan said in a video. The embarrassment, it seems, was ample punishment. No disciplinary action was taken against the students -- but they definitely got a schooling. "Life lesson: if you're going to apologize, don't use ChatGPT to do it," Flanagan said in the video.

[5]

Their professors caught them cheating. They used AI to apologise.

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign professors discovered students used artificial intelligence to write apologies for cheating and faking attendance. The professors revealed the AI-generated messages in a lecture, teaching a lesson on academic integrity. No disciplinary action was taken against the students. The incident highlights the growing challenge of AI in education. Confronted with allegations that they had cheated in an introductory data science course and fudged their attendance, dozens of undergraduates at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign recently sent two professors a mea culpa via email. But there was one problem, a glaring one: They had not written the emails. Artificial intelligence had, according to the professors, Karle Flanagan and Wade Fagen-Ulmschneider, an academic pair known to their students and social media followers as the Data Science Duo. The students got their comeuppance in a large lecture hall Oct. 17, when the professors read aloud their identical, less-than-genuine apologies from a projector screen, video from that class showed. Busted. The professors posted about it on social media, where the gotcha moment drew widespread attention. "They said, 'Dear Professor Flanagan, I want to sincerely apologize,'" Flanagan said. "And I was like, Thank you. They're owning up to it. They're apologizing. And then I got another email, the second email, and then the third. And then everybody sort of sincerely apologizing, and suddenly it became a little less sincere." At a time when educational institutions are grappling with the intrusion of machine learning into classrooms and homework assignments, the professors said they decided to use the episode to teach a lesson in academic integrity. They did not take disciplinary action against the students. "You can hear the students laugh in the background of the video," Fagen-Ulmschneider said. "They knew that it was something that they could see themselves doing." It was not clear if the University of Illinois would punish the students who were involved. The university did not immediately respond to a request for comment Wednesday. Although the university's student code covers cheating and plagiarism, the professors said that they were not aware of specific rules applying to the use of AI. About 1,200 students take the course, which is divided into two sections that meet Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Attendance and participation in the lectures count for 4% of the final grade in the class, which is primarily taken by first-year students. To track the engagement of the class, the professors created an application known as the Data Science Clicker that requires students to log in on their phones or computers and, when prompted by a QR code, answer a multiple-choice question in a certain amount of time, usually about 90 seconds. But in early October, the professors said they began to grow suspicious when dozens of students who were absent from class were still answering the questions. So the teachers said they started checking how many times students refreshed the site and the IP addresses of their devices, and began reviewing server logs. "Sometimes on Fridays, some students will go up to Chicago," said Fagen-Ulmschneider, 40, a teaching professor in the Siebel School of Computing and Data Science. It appeared that the students had been tipped off about the questions and when they had to respond, according to the professors, who sent emails to more than 100 students telling them that the ruse was up. "We take academic integrity very seriously here, so we wanted to make sure to give them a warning," said Flanagan, 36, a teaching associate professor in the Department of Statistics. Alex Von Holten, 20, a sophomore who took the class in the spring semester this year, said he wasn't surprised to learn that some students had been "sleepwalking" through it. The format, a large lecture with introductory material, might lead some people to slack off, he said. "It's really hard not to get an A in that class," Von Holten said. To do worse, he added, "you have to genuinely just not show up and not care." Vinayak Bagdi, 21, who graduated in May with a degree in statistics, took the class as a freshman to fulfill his academic requirements. Four years later, he said, the professors' dedication to demystifying statistics had stuck with him. He said he never felt bombarded with information or too lost to keep up with assignments in the class, and he described the professors as being heavily invested in the success of students. That made it especially disheartening that some students had used AI, Bagdi said. "You're not even coming to the class, and then you can't even send a sincere email to the professor saying, 'I apologize'?" he said. "Out of any class at the university, why skip that one?" This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Share

Share

Copy Link

University of Illinois professors discovered students used AI to write apologies after being caught cheating on attendance and assignments. The incident went viral and sparked broader discussions about AI's impact on education and academic integrity.

The Incident That Went Viral

Two University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign professors, Karle Flanagan and Wade Fagen-Ulmschneider, known as the "Data Science Duo," discovered a troubling pattern in their introductory data science course this fall. After catching over 100 students cheating on attendance requirements, they received what initially appeared to be heartfelt apologies from the accused students. However, upon closer examination, they realized that approximately 80% of these apology emails were generated by artificial intelligence

1

3

.

Source: NYT

The professors confronted their students during a lecture on October 17, displaying the nearly identical apologies on a projector screen, each containing the phrase "sincerely apologize." The moment was captured on video and quickly went viral across social media platforms, sparking widespread discussion about AI's impact on academic integrity

4

.How the Cheating Scheme Worked

The Data Science Discovery course, which enrolls approximately 1,200 students across multiple sections, uses a system called the "Data Science Clicker" to track attendance and participation, worth 4% of the final grade. Students must scan a QR code during class and answer a multiple-choice question within 90 seconds to receive credit for attendance

3

5

.

Source: The Verge

In early October, the professors noticed that significantly more students were answering the attendance questions than were physically present in the lecture hall. Their investigation revealed that absent students were being tipped off by classmates about when the questions went live, allowing them to respond remotely and falsely claim attendance credit

1

.The Broader AI Cheating Epidemic

This incident represents just the tip of the iceberg in what educators describe as a widespread crisis. According to teaching assistants and course staff cited in the coverage, AI-generated content has become pervasive across academic assignments. One teaching assistant reported that "it's insane how pervasive AI slop is in 75% of the turned-in work," while another noted that even simple 75-word weekly paragraphs were being AI-generated

1

.

Source: Ars Technica

The problem has been exacerbated by the introduction of AI agents - automated tools that can complete online tasks independently. These sophisticated systems can now seamlessly submit assignments, take quizzes, and even participate in discussion forums designed for student interaction

2

.Related Stories

Tech Companies' Role in Educational Disruption

Tech companies have actively marketed their AI tools to students through promotional offers and targeted advertising. OpenAI offered free ChatGPT Plus access to college students "to help through finals," while Perplexity provides free yearlong access to its premium services and pays $20 referrals for student sign-ups

2

.Perplexity has been particularly brazen in its marketing approach, releasing Facebook and Instagram ads showing students how to use AI agents for homework completion. When confronted about enabling cheating, Perplexity spokesperson Beejoli Shah dismissed concerns, stating that "every learning tool since the abacus has been used for cheating" and that "cheaters in school ultimately only cheat themselves"

2

.Educational Institutions Struggle to Respond

Educational technology platforms like Canvas, used by "every Ivy League school" and "40% of U.S. K-12 districts," face technical challenges in blocking AI agents. When college instructional designer Yun Moh contacted Instructure (Canvas's parent company) about preventing AI agents from impersonating students, the company suggested this was a philosophical rather than technical problem that shouldn't impede educational progress

2

.The University of Illinois professors chose not to pursue disciplinary action against the students involved, instead treating the incident as a "life lesson" about academic integrity. However, the university has not clarified whether specific policies exist regarding AI use in academic work

3

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[4]

Related Stories

Student Demands Tuition Refund After Catching Professor Using ChatGPT

15 May 2025•Technology

Schools Launch AI Literacy Programs as 60% of Teens Report Peers Using AI to Cheat

22 Feb 2026•Entertainment and Society

AI in Education: Reshaping Learning and Challenging Academic Integrity

12 Sept 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Pentagon Summons Anthropic CEO as $200M Contract Faces Supply Chain Risk Over AI Restrictions

Policy and Regulation

3

Canada Summons OpenAI Executives After ChatGPT User Became Mass Shooting Suspect

Policy and Regulation