AI and Copyright: Navigating the Legal Landscape of Machine Learning

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Opinion | How to tell when AI models infringe copyright

A recent court ruling uses the marketplace to define the boundaries of intellectual property. A gangbusters few years for generative artificial intelligence has led to an explosion of copyright lawsuits. Large-language models such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Dall-E and Midjourney devour information from across the internet as part of their training. Many of the creators of these inputs believe that their intellectual property rights are being infringed. A judge recently gave them reason for hope. Going forward, the ruling offers a useful way to think about what puts an AI model on the wrong side of the line between creating fresh content and pilfering what's already there. The media company Thomson Reuters was the aggrieved party in the case. In 2020, it sued a firm called Ross Intelligence on behalf of the legal research company Westlaw, a Thomson Reuters property. The company complained that Ross Intelligence had improperly trained its AI tool on Westlaw research summaries without licensing them. After initially deciding against Westlaw, a federal circuit court judge ruled in its favor, finding that the way in which Ross Intelligence used its material did not qualify as "fair use." This decision sounds, and is, awfully technical. But the case's implications are meaningful for AI and the industries on whose work neural networks rely -- to produce surrealist portraits of poodles, for example, or analyze the writings of Immanuel Kant. The basic complaint that artists, writers and, apparently, legal scholars make about AI companies is that these firms are earning millions, even billions, of dollars by training their models on the creators' work, and then competing with those same creators by selling the same kind of work in the marketplace. AI companies argue that they're not violating copyright because, well, they're not copying. Yes, they're ingesting written and visual matter of all shapes and sizes as they develop -- but what they ultimately produce is something new. They are, they say, unleashing a modern kind of creativity, in which people collaborate with their AI models to produce art, literature, thought and even journalism never seen before. The AI developers' legal position is strong. They aren't allowed to spit out identical or near-identical replicas of existing books, plays, paintings and so on. But they are allowed to replicate facts, concepts and even forms. Ask an LLM to draw something in the style of Salvador Dalí, for instance, and it probably won't get away with producing his "The Persistence of Memory" with barely noticeable alterations. It can, however, produce objects that seem to melt in the sun, or something that contemplates time. Fair use has been a big part of AI companies' defense. No matter how well a plaintiff manages to argue that a given AI model infringes copyright, the AI maker can usually point to the doctrine of fair use, which requires consideration of multiple factors, including the purpose of the use (here, criticism, comment and research are favored) and the effect of the use on the marketplace. If, in using a copied work, an AI model adds "something new," it is probably in the clear. Thomson Reuters successfully argued that Ross Intelligence was siphoning Westlaw's data to develop a competing product -- and, moreover, that this competing product failed to add anything new to the marketplace. As it turns out, Ross's tool did not actually qualify as generative AI. That's because, as the judge put it, its product (now defunct) used Westlaw's headnotes merely to help it return "relevant judicial opinions that have already been written," rather than to craft summaries of its own. But the decision helps clarify the purpose of copyright law in the AI age more broadly: to protect creators against models that are designed not to advance creativity, but to snuff out human creations by underselling them in the marketplace. Certainly, the AI industry needs room to grow. But creative industries need it, too. In sorting out what's fair, courts will continue to have to consider the conundrum addressed in the Thomson Reuters case. The goal of copyright is to promote progress. Sometimes AI can do that, and other times it gets in the way.

[2]

Should AI be treated the same way as people are when it comes to copyright law?

The New York Times's lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft highlights an uncomfortable contradiction in how we view creativity and learning. While the Times accuses these companies of copyright infringement for training AI on their content, this ignores a fundamental truth: AI systems learn exactly as humans do, by absorbing, synthesizing and transforming existing knowledge into something new. Consider how human creators work. No writer, artist or musician exists in a vacuum. For example, without ancient Greek mythology, we wouldn't have DC's pantheon of superheroes, including cinematic staples such as Superman, Wonder Woman and Aquaman. These characters draw unmistakably clear inspiration from the likes of Zeus, Athena and Poseidon, respectively. Without the gods of Mount Olympus as inspiration, there would be no comic book heroes today to save the world (and the summer box office). This pattern of learning, absorbing and transforming is precisely how large language models (LLMs) operate. They don't plagiarize or reproduce; they learn patterns and relationships from vast amounts of information, just as humans do. When a novelist reads thousands of books throughout their lifetime, those works shape their writing style, vocabulary and narrative instincts. We don't accuse them of copyright infringement because we understand that transforming influences into original expression is the essence of creativity. Critics will argue that AI companies profit from others' work without compensation. This argument misses a crucial distinction between reference and reproduction. When LLMs generate text that bears stylistic similarities to works they trained on, it's no different from a human author whose writing reflects their literary influences. The output isn't a copy, it's a new creation informed by patterns the system has learned. Others might contend that the commercial nature of AI training sets it apart from human learning. However, this ignores how human creativity has always been commercialized. Publishing houses profit from authors whose styles developed by reading other published works. Hollywood studios earn billions from films that remix existing narrative traditions. The economy of human creativity has always involved building commercial works upon the foundation of cultural knowledge. Moreover, this economic reality aligns perfectly with the Constitution's original intent for intellectual property. Article I, Section 8 explicitly empowers Congress "to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts" through copyright law -- not simply to protect content creators, but to advance human knowledge and innovation. Allowing AI systems to learn from existing works furthers this constitutional purpose by fostering new economic activity and technological progress. It's also crucial to recognize that when verbatim copying occurs in AI outputs, it almost always results from specific user prompts, not the inherent nature of the AI system itself. This highlights how LLMs are tools, capable of being used responsibly or abused for copyright infringement based entirely on how users interact with them. That LLMs can be used to violate copyrights is logically little different than how a hammer can be used as a deadly weapon. Common sense tells us that a hammer's potential for violent assault doesn't justify treating it as an inherently dangerous weapon, as said usage represents a rare exception of its use rather than the norm. The Sony v. Universal Studios case of 1984 illustrated this logic legally when the Supreme Court ruled that VCRs were not illegal because they had "substantial non-infringing uses," despite their potential to be used for copyright violations. This exact case gives courts the legal framework to side with AI companies today, as LLMs clearly offer tremendous value entirely separate from any potential copyright concerns. While there remains a good chance that OpenAI will emerge victorious in their legal battle, we should not rely on courts alone to reach the correct conclusion in these cases. Congress must act to clarify copyright law for the AI age, just as it did when photography and recorded music disrupted prior understandings of intellectual property. When photography first emerged in the 19th century, courts struggled to determine whether photographs deserved copyright protection or were merely mechanical reproductions of reality. Congress eventually stepped in, recognizing photography as a creative medium deserving protection. Similarly, when player pianos and phonographs emerged, enabling mechanical reproduction of music, Congress created the compulsory licensing system in the 1909 Copyright Act rather than allowing copyright holders to block the technology entirely. Today's situation demands similar legislative vision. Rather than allowing the risk of a judicial interpretation that strangles innovation, Congress should immediately move to establish a clear framework that recognizes AI training as fundamentally transformative and non-infringing.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Recent court rulings and ongoing debates highlight the complex intersection of AI, copyright law, and intellectual property rights, as the industry grapples with defining fair use in the age of machine learning.

AI Copyright Infringement: A Legal Tug-of-War

The rapid advancement of generative artificial intelligence has sparked a surge in copyright lawsuits, as creators and companies grapple with the boundaries of intellectual property rights in the digital age. A recent court ruling in favor of Thomson Reuters against Ross Intelligence has shed light on how to determine when AI models infringe on copyrights, offering a potential framework for future cases

1

.The Thomson Reuters Case: A Landmark Decision

The case centered around Ross Intelligence's use of Westlaw research summaries, owned by Thomson Reuters, to train its AI tool. The federal circuit court judge ruled that this use did not qualify as "fair use," setting a precedent for how AI companies might be held accountable for their training data

1

.Defining Fair Use in the AI Era

The ruling emphasizes the importance of considering the effect of AI models on the marketplace. If an AI product is designed to compete directly with human-created content without adding significant value, it may be more likely to be found in violation of copyright laws. This decision helps clarify the purpose of copyright law in the AI age: to protect creators against models that aim to replace human creations rather than advance creativity

1

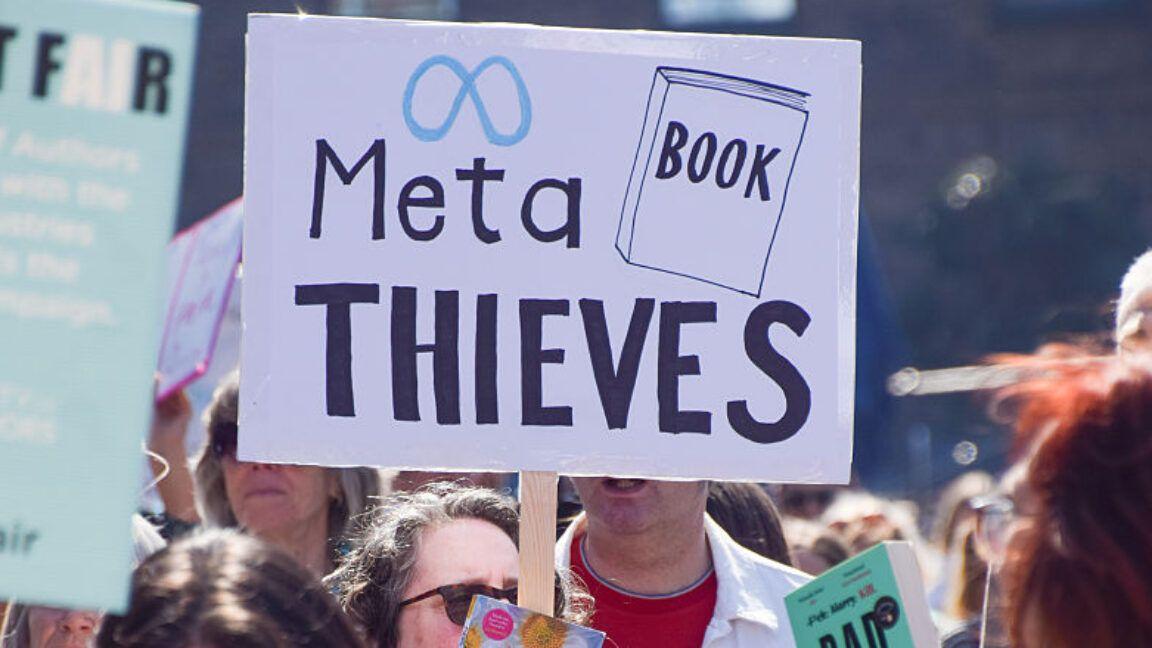

.The New York Times Lawsuit: A Different Perspective

In contrast to the Thomson Reuters case, The New York Times's lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft highlights a different aspect of the debate. Critics argue that this lawsuit ignores the fundamental similarity between how AI systems and humans learn – by absorbing, synthesizing, and transforming existing knowledge into something new

2

.AI Learning vs. Human Creativity

Proponents of AI argue that large language models (LLMs) operate similarly to human creators, who are influenced by countless works throughout their lives without being accused of copyright infringement. They contend that AI-generated content, like human-created work, is a new creation informed by learned patterns rather than a direct copy

2

.Related Stories

The Economic Argument

While some argue that AI companies profit from others' work without compensation, supporters of AI point out that human creativity has always been commercialized in similar ways. Publishing houses and Hollywood studios have long profited from works that build upon existing cultural knowledge

2

.Legal Precedents and Future Legislation

The Sony v. Universal Studios case of 1984 provides a potential legal framework for courts to side with AI companies, as it established that technologies with "substantial non-infringing uses" are not inherently illegal. However, many argue that Congress must act to clarify copyright law for the AI age, much as it did for photography and recorded music in the past

2

.The Path Forward

As the AI industry continues to evolve, courts and legislators will need to balance the protection of intellectual property rights with the promotion of innovation and progress. The goal of copyright law, as stated in the U.S. Constitution, is to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts." Finding the right balance between protecting creators and fostering AI development will be crucial in achieving this aim

1

2

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

Related Stories

Judges Side with AI Companies in Copyright Cases, but Leave Door Open for Future Challenges

25 Jun 2025•Policy and Regulation

OpenAI and Google Push for Relaxed Copyright Laws in AI Development

14 Mar 2025•Policy and Regulation

Legal Battles Over AI Training: Courts Rule on Fair Use, Authors Fight Back

15 Jul 2025•Policy and Regulation

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Meta strikes up to $100 billion AI chips deal with AMD, could acquire 10% stake in chipmaker

Technology

3

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with supply chain risk label over AI safeguards for military use

Policy and Regulation