The Looming Threat of AI Model Collapse: Accuracy, Ethics, and the Future of Information

5 Sources

5 Sources

[1]

AI model collapse is not what we paid for

Opinion I use AI a lot, but not to write stories. I use AI for search. When it comes to search, AI, especially Perplexity, is simply better than Google. Ordinary search has gone to the dogs. Maybe as Google goes gaga for AI, its search engine will get better again, but I doubt it. In just the last few months, I've noticed that AI-enabled search, too, has been getting crappier. In particular, I'm finding that when I search for hard data such as market-share statistics or other business numbers, the results often come from bad sources. Instead of stats from 10-Ks, the US Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC) mandated annual business financial reports for public companies, I get numbers from sites purporting to be summaries of business reports. These bear some resemblance to reality, but they're never quite right. If I specify I want only 10-K results, it works. If I just ask for financial results, the answers get... interesting, This isn't just Perplexity. I've done the exact same searches on all the major AI search bots, and they all give me "questionable" results. Welcome to Garbage In/Garbage Out (GIGO). Formally, in AI circles, this is known as AI model collapse. In an AI model collapse, AI systems, which are trained on their own outputs, gradually lose accuracy, diversity, and reliability. This occurs because errors compound across successive model generations, leading to distorted data distributions and "irreversible defects" in performance. The final result? A Nature 2024 paper stated, "The model becomes poisoned with its own projection of reality." Model collapse is the result of three different factors. The first is error accumulation, in which each model generation inherits and amplifies flaws from previous versions, causing outputs to drift from original data patterns. Next, there is the loss of tail data: In this, rare events are erased from training data, and eventually, entire concepts are blurred. Finally, feedback loops reinforce narrow patterns, creating repetitive text or biased recommendations. I like how the AI company Aquant puts it: "In simpler terms, when AI is trained on its own outputs, the results can drift further away from reality." I'm not the only one seeing AI results starting to go downhill. In a recent Bloomberg Research study of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), the financial media giant found that 11 leading LLMs, including GPT-4o, Claude-3.5-Sonnet, and Llama-3-8 B, using over 5,000 harmful prompts would produce bad results. RAG, for those of you who don't know, enables large language models (LLMs) to pull in information from external knowledge stores, such as databases, documents, and live in-house data stores, rather than relying just on the LLMs' pre-trained knowledge. You'd think RAG would produce better results, wouldn't you? And it does. For example, it tends to reduce AI hallucinations. But, simultaneously, it increases the chance that RAG-enabled LLMs will leak private client data, create misleading market analyses, and produce biased investment advice. As Amanda Stent, Bloomberg's head of AI strategy & research in the office of the CTO, explained: "This counterintuitive finding has far-reaching implications given how ubiquitously RAG is used in gen AI applications such as customer support agents and question-answering systems. The average internet user interacts with RAG-based systems daily. AI practitioners need to be thoughtful about how to use RAG responsibly." That sounds good, but a "responsible AI user" is an oxymoron. For all the crap about how AI will encourage us to spend more time doing better work, the truth is AI users write fake papers including bullshit results. This ranges from your kid's high school report to fake scientific research documents to the infamous Chicago Sun-Times best of summer feature, which included forthcoming novels that don't exist. What all this does is accelerate the day when AI becomes worthless. For example, when I asked ChatGPT, "What's the plot of Min Jin Lee's forthcoming novel 'Nightshade Market?'" one of the fake novels, ChatGPT confidently replied, "There is no publicly available information regarding the plot of Min Jin Lee's forthcoming novel, Nightshade Market. While the novel has been announced, details about its storyline have not been disclosed." Once more, and with feeling, GIGO. Some researchers argue that collapse can be mitigated by mixing synthetic data with fresh human-generated content. What a cute idea. Where is that human-generated content going to come from? Given a choice between good content that requires real work and study to produce and AI slop, I know what most people will do. It's not just some kid wanting a B on their book report of John Steinbeck's The Pearl; it's businesses eager, they claim, to gain operational efficiency, but really wanting to fire employees to increase profits. Quality? Please. Get real. We're going to invest more and more in AI, right up to the point that model collapse hits hard and AI answers are so bad even a brain-dead CEO can't ignore it. How long will it take? I think it's already happening, but so far, I seem to be the only one calling it. Still, if we believe OpenAI's leader and cheerleader, Sam Altman, who tweeted in February 2024 that "OpenAI now generates about 100 billion words per day," and we presume many of those words end up online, it won't take long. ®

[2]

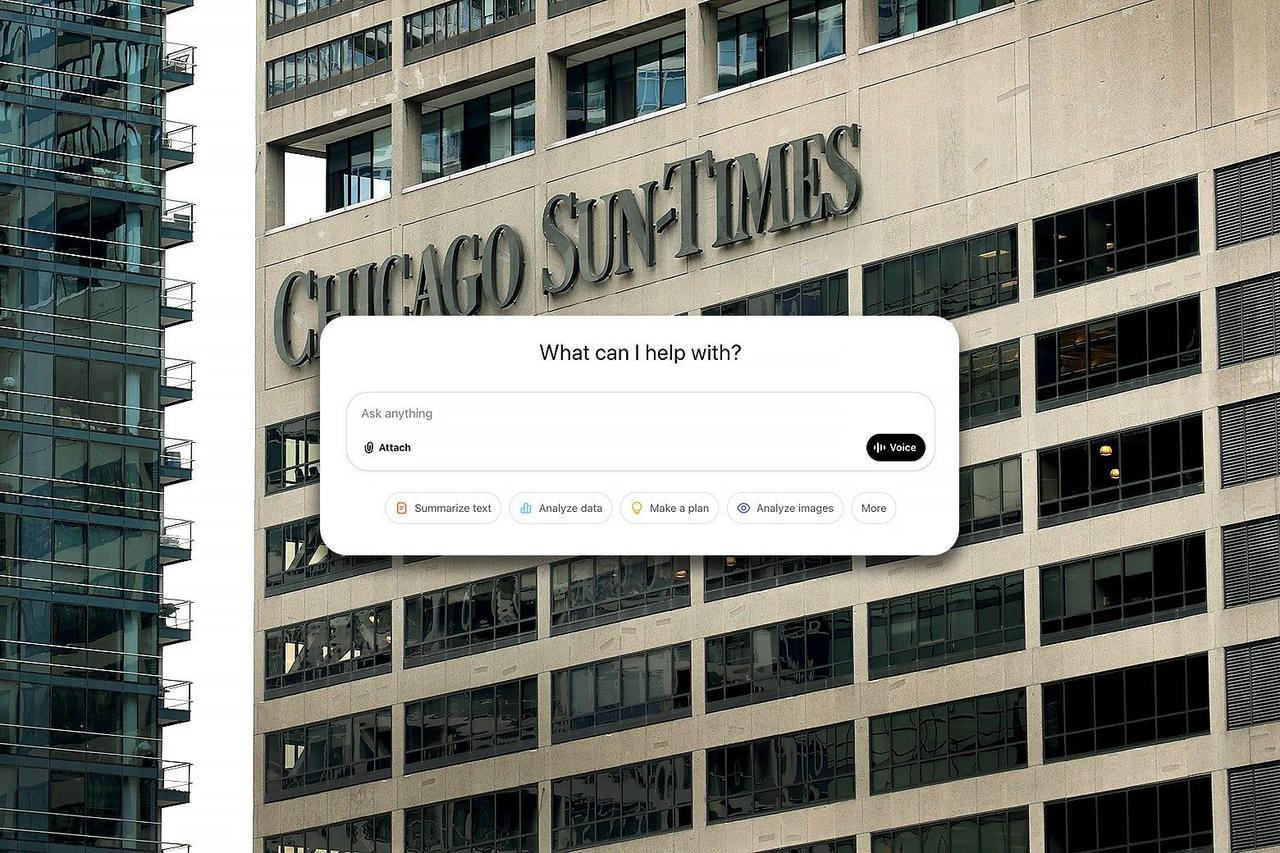

Slop the Presses

At least two newspapers published an insert littered with AI fabrications. How did this happen? At first glance, "Heat Index" appears as inoffensive as newspaper features get. A "summer guide" sprawling across more than 50 pages, the feature, which was syndicated over the past week in both the Chicago Sun-Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer, contains "303 Must-Dos, Must-Tastes, and Must-Tries" for the sweaty months ahead. Readers are advised in one section to "Take a moonlight hike on a well-marked trail" and "Fly a kite on a breezy afternoon." In others, they receive tips about running a lemonade stand and enjoying "unexpected frozen treats." Yet close readers of the guide noticed that something was very off. "Heat Index" went viral earlier today when people on social media pointed out that its summer-reading guide matched real authors with books they haven't written, such as Nightshade Market, attributed to Min Jin Lee, and The Last Algorithm, attributed to Andy Weir -- a hint that the story may have been composed by a chatbot. This turned out to be true. Slop has come for the regional newspapers. Originally written for King Features, a division of Hearst, "Heat Index" was printed as a kind of stand-alone magazine and inserted into the Sun-Times, the Inquirer, and possibly other newspapers, beefing the publications up without staff writers and photographers having to do additional work themselves. Although many of the elements of "Heat Index" do not have an author's byline, some of them were written by a freelancer named Marco Buscaglia. When we reached out to him, he admitted to using ChatGPT for his work. Buscaglia explained that he had asked the AI to help him come up with book recommendations. He hasn't shied away from using these tools for research: "I just look for information," he said. "Say I'm doing a story, 10 great summer drinks for your barbecue or whatever. I'll find things online and say, hey, according to Oprah.com, a mai tai is a perfect drink. I'll source it; I'll say where it's from." This time, at least, he did not actually check the chatbot's work. What's more, Buscaglia said that he submitted his first draft to King, which apparently accepted it without substantive changes and distributed it for syndication. King Features did not respond to a request for comment. Buscaglia (who also admitted his AI use to 404 Media) seemed to be under the impression that the summer-reading article was the only one with problems, though this is not the case. For example, in a section on "hammock hanging ethics," Buscaglia quotes a "Mark Ellison, resource management coordinator for Great Smoky Mountains National Park." There is indeed a Mark Ellison who works in the Great Smoky Mountains region -- not for the national park, but for a company he founded called Pinnacle Forest Therapy. Ellison told us via email that he'd previously written an article about hammocks for North Carolina's tourism board, offering that perhaps that is why his name was referenced in Buscaglia's chatbot search. But that was it: "I have never worked for the park service. I never communicated with this person." When we mentioned Ellison's comments, Buscaglia expressed that he was taken aback and surprised by his own mistake. "There was some majorly missed stuff by me," he said. "I don't know. I usually check the source. I thought I sourced it: He said this in this magazine or this website. But hearing that, it's like, Obviously he didn't." Another article in "Heat Index" quotes a "Dr. Catherine Furst," purportedly a food anthropologist at Cornell University, who, according to a spokesperson for the school, does not actually work there. Such a person does not seem to exist at all. For this material to have reached print, it should have had to pass through a human writer, human editors at King, and human staffers at the Chicago Sun-Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer. No one stopped it. Victor Lim, a spokesperson for the Sun-Times, told us, "This is licensed content that was not created by, or approved by, the Sun-Times newsroom, but it is unacceptable for any content we provide to our readers to be inaccurate." A longer statement posted on the paper's website (and initially hidden behind a paywall) said in part, "This should be a learning moment for all of journalism." Lisa Hughes, the publisher and CEO of the Inquirer, told us the publication was aware the supplement contained "apparently fabricated, outright false, or misleading" material. "We do not know the extent of this but are taking it seriously and investigating," she said via email. Hughes confirmed that the material was syndicated from King Features, and added, "Using artificial intelligence to produce content, as was apparently the case with some of the Heat Index material, is a violation of our own internal policies and a serious breach." (Although each publication blames King Features, both the Sun-Times and the Inquirer affixed their organization's logo to the front page of "Heat Index" -- suggesting ownership of the content to readers.) There are layers to this story, all of them a depressing case study. The very existence of a package like "Heat Index" is the result of a local-media industry that's been hollowed out by the internet, plummeting advertising, private-equity firms, and a lack of investment and interest in regional newspapers. In this precarious environment, thinned-out and underpaid editorial staff under constant threat of layoffs and with few resources are forced to cut corners for publishers who are frantically trying to turn a profit in a dying industry. It stands to reason that some of these harried staffers, and any freelancers they employ, now armed with automated tools such as generative AI, would use them to stay afloat. Buscaglia said that he has sometimes seen rates as low as $15 for 500 words, and that he completes his freelance work late at night after finishing his day job, which involves editing and proofreading for AT&T. Thirty years ago, Buscaglia said, he was an editor at the Park Ridge Times Herald, a small weekly paper that was eventually rolled up into Pioneer Press, a division of the Tribune Publishing Company. "I loved that job," he said. "I always thought I would retire in some little town -- a campus town in Michigan or Wisconsin -- and just be editor of their weekly paper. Now that doesn't seem that possible." (A librarian at the Park Ridge Public Library accessed an archive for us and confirmed that Buscaglia had worked for the paper.) On one level, "Heat Index" is just a small failure of an ecosystem on life support. But it is also a template for a future that will be defined by the embrace of artificial intelligence across every industry -- one where these tools promise to unleash human potential, but instead fuel a human-free race to the bottom. Any discussion about AI tends to be a perpetual, heady conversation around the ability of these tools to pass benchmark tests or whether they can or could possess something approximating human intelligence. Evangelists discuss their power as educational aids and productivity enhancers. In practice, the marketing language around these tools tends not to capture the ways that actual humans use them. A Nobel Prize-winning work driven by AI gets a lot of run, though the dirty secret of AI is that it is surely more often used to cut corners and produce lowest-common-denominator work. Venture capitalists speak of a future in which AI agents will sort through the drudgery of daily busywork and free us up to live our best lives. Such a future could come to pass. The present, however, offers ample proof of a different kind of transformation, powered by laziness and greed. AI usage and adoption tends to find weaknesses inside systems and exploit them. In academia, generative AI has upended the traditional education model, based around reading, writing, and testing. Rather than offer a new way forward for a system in need of modernization, generative-AI tools have broken it apart, leaving teachers and students flummoxed, even depressed, and unsure of their own roles in a system that can be so easily automated. AI-generated content is frequently referred to as slop because it is spammy and flavorless. Generative AI's output often becomes content in essays, emails, articles, and books much in the way that packing peanuts are content inside shipped packages. It's filler -- digital lorem ipsum. The problem with slop is that, like water, it gets in everywhere and seeks the lowest level. Chatbots can assist with higher-level tasks like coding or scanning and analyzing a large corpus of spreadsheets, document archives, or other structured data. Such work marries human expertise with computational heft. But these more elegant examples seem exceedingly rare. In a recent article, Zach Seward, the editorial director of AI initiatives at The New York Times said that, while the newspaper uses artificial intelligence to parse websites and datasets to assist with reporting, he views AI on its own as little more than a "parlor trick," mostly without value when not in the hands of already skilled reporters and programmers. Speaking with Buscaglia, we could easily see how the "Heat Index" mistake could become part of a pattern for journalists swimming against a current of synthetic slop, constantly produced content, and unrealistic demands from publishers. "I feel like my role has sort of evolved. Like, if people want all this content, they know that I can't write 48 stories or whatever it's going to be," he said. He talked about finding another job, perhaps as a "shoe salesman." One worst-case scenario for AI looks a lot like the "Heat Index" fiasco -- the parlor tricks winning out. It is a future where, instead of an artificial-general-intelligence apocalypse, we get a far more mundane destruction. AI tools don't become intelligent, but simply good enough. They are not deployed by people trying to supplement or enrich their work and potential, but by those looking to automate it away entirely. You can see the contours of that future right now: in anecdotes about teachers using AI to grade papers written primarily by chatbots or in AI-generated newspaper inserts being sent to households that use them primarily as birdcage liners and kindling. Parlor tricks met with parlor tricks -- robots talking to robots, writing synthetic words for audiences who will never read them.

[3]

AI is rotting your brain and making you stupid

How are you using new AI technology? Maybe you're only deploying things like ChatGPT to summarize long texts or draft up mindless emails. But what are you losing by taking these shortcuts? And is this tech taking away our ability to think? For nearly 10 years I have written about science and technology and I've been an early adopter of new tech for much longer. As a teenager in the mid-1990s I annoyed the hell out of my family by jamming up the phone line for hours with a dial-up modem; connecting to bulletin board communities all over the country. When I started writing professionally about technology in 2016 I was all for our seemingly inevitable transhumanist future. When the chip is ready I want it immediately stuck in my head, I remember saying proudly in our busy office. Why not improve ourselves where we can? Since then, my general view on technology has dramatically shifted. Watching a growing class of super-billionaires erode the democratizing nature of technology by maintaining corporate controls over what we use and how we use it has fundamentally changed my personal relationship with technology. Seeing deeply disturbing philosophical stances like longtermism, effective altruism, and singulartarianism envelop the minds of those rich, powerful men controlling the world has only further entrenched inequality. A recent Black Mirror episode really rammed home the perils we face by having technology so controlled by capitalist interests. A sick woman is given a brain implant connected to a cloud server to keep her alive. The system is managed through a subscription service where the user pays for monthly access to the cognitive abilities managed by the implant. As time passes, that subscription cost gets more and more expensive - and well, it's Black Mirror, so you can imagine where things end up. The enshittification of our digital world has been impossible to ignore. You're not imagining things, Google Search is getting worse. But until the emergence of AI (or, as we'll discuss later, language learning models that pretend to look and sound like an artificial intelligence) I've never been truly concerned about a technological innovation, in and of itself. A recent article looked at how generative AI tech such as ChatGPT is being used by university students. The piece was authored by a tech admin at New York University and it's filled with striking insights into how AI is shaking the foundations of educational institutions. No unsurprisingly, students are using ChatGPT for everything from summarizing complex texts to completely writing essays from scratch. But one of the reflections quoted in the article immediately jumped out at me. When a student was asked why they relied on generative AI so much when putting work together they responded, "You're asking me to go from point A to point B, why wouldn't I use a car to get there?" My first response was, of course, why wouldn't you? It made complete sense. For a second. And then I thought, hang on, what is being lost by speeding from point A to point B in a car? Let's further the analogy. You need to go to the grocery store. It's a 10-minute walk away but a three-minute drive. Why wouldn't you drive? Well, the only benefit of driving is saving time. That's inarguable. You'll be back home and cooking up your dinner before the person on foot even gets to the grocery store. Congratulations. You saved yourself about 20 minutes. In a world where efficiency trumps everything this is the best choice. Use that extra 20 minutes in your day wisely. But what are the benefits of not driving, taking the extra time, and walking? First, you have environmental benefits. Not using a car unnecessarily; spewing emissions into the air, either directly from combustion or indirectly for those with electric cars. Secondly, you have health benefits from the little bit of exercise you get by walking. Our stationary lives are quite literally killing us so a 20-minute walk a day is likely to be incredibly positive for your health. But there are also more abstract benefits to be gained by walking this short trip from A to B. Walking connects us to our neighborhood. It slows things down. Helps us better understand the community and environment we are living in. A recent study summarized the benefits of walking around your neighborhood, suggesting the practice leads to greater social connectedness and reduced feelings of isolation. So what are we losing when we use a car to get from point A to point B? Potentially a great deal. But let's move out of abstraction and into the real world. An article in the Columbia Journalism Review asked nearly 20 news media professionals how they were integrating AI into their personal workflow. The responses were wildly varied. Some journalists refused to use AI for anything more than superficial interview transcription, while others use it broadly, to edit text, answer research questions, summarize large bodies of science text, or search massive troves of data for salient bits of information. In general, the line almost all those media professionals shared was they would never explicitly use AI to write their articles. But for some, almost every other stage of the creative process in developing a story was fair game for AI assistance. I found this a little horrifying. Farming out certain creative development processes to AI felt not only ethically wrong but also like key cognitive stages were being lost, skipped over, considered unimportant. I've never considered myself to be an extraordinarily creative person. I don't feel like I come up with new or original ideas when I work. Instead, I see myself more as a compiler. I enjoy finding connections between seemingly disparate things. Linking ideas and using those pieces as building blocks to create my own work. As a writer and journalist I see this process as the whole point. A good example of this is a story I published in late 2023 investigating the relationship between long Covid and psychedelics. The story began earlier in the year when I read an intriguing study linking long Covid with serotonin abnormalities in the gut. Being interested in the science of psychedelics, and knowing that psychedelics very much influence serotonin receptors, I wondered if there could be some kind of link between these two seemingly disparate topics. The idea sat in the back of my mind for several months, until I came across a person who told me they had been actively treating their own long Covid symptoms with a variety of psychedelic remedies. After an expansive and fascinating interview I started diving into different studies looking to understand how certain psychedelics affect the body, and whether there could be any associations with long Covid treatments. Eventually I stumbled across a few compelling associations. It took weeks of reading different scientific studies, speaking to various researchers, and thinking about how several discordant threads could be somehow linked. Could AI have assisted me in the process of developing this story? No. Because ultimately, the story comprised an assortment of novel associations that I drew between disparate ideas all encapsulated within the frame of a person's subjective experience. And it is this idea of novelty that is key to understanding why modern AI technology is not actually intelligence but a simulation of intelligence. ChatGPT, and all the assorted clones that have emerged over the last couple of years, are a form of technology called LLMs (large language models). At the risk of enraging those who actually work in this mind-bendingly complex field, I'm going to dangerously over-simplify how these things work. It's important to know that when you ask a system like ChatGPT a question it doesn't understand what you are asking it. The response these systems generate to any prompt is simply a simulation of what it computes a response would look like based on a massive dataset. So if I were to ask the system a random question like, "What color are cats?", the system would scrape the world's trove of information on cats and colors to create a response that mirrors the way most pre-existing text talks about cats and colors. The system builds its response word by word, creating something that reads coherently to us, by establishing a probability for what word should follow each prior word. It's not thinking, it's imitating. What these generative AI systems are spitting out are word salad amalgams of what it thinks the response to your prompt should look like, based on training from millions of books and webpages that have been previously published. Setting aside for a moment the accuracy of the responses these systems deliver, I am more interested (or concerned) with the cognitive stages that this technology allows us to skip past. For thousands of years we have used technology to improve our ability to manage highly complex tasks. The idea is called cognitive offloading, and it's as simple as writing something down on a notepad or saving a contact number on your smartphone. There are pros and cons to cognitive offloading, and scientists have been digging into the phenomenon for years. As long as we have been doing it, there have been people criticizing the practice. The legendary Greek philosopher Socrates was notorious for his skepticism around the written word. He believed knowledge emerged through a dialectical process so writing itself was reductive. He even went so far as to suggest (according to his student Plato, who did write things down) that writing makes us dumber. Almost every technological advancement in human history can be seen to be accompanied by someone suggesting it will be damaging. Calculators have destroyed our ability to properly do math. GPS has corrupted our spatial memory. Typewriters killed handwriting. Computer word processors killed typewriters. Video killed the radio star. And what have we lost? Well, zooming in on writing, for example, a 2020 study claimed brain activity is greater when a note is handwritten as opposed to being typed on a keyboard. And then a 2021 study suggested memory retention is better when using a pen and paper versus a stylus and tablet. So there are certainly trade-offs whenever we choose to use a technological tool to offload a cognitive task. There's an oft-told story about gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. It may be apocryphal but it certainly is meaningful. He once said he sat down and typed out the entirety of The Great Gatsby, word for word. According to Thompson, he wanted to know what it felt like to write a great novel. I don't want to get all wishy-washy here, but these are the brass tacks we are ultimately falling on. What does it feel like to think? What does it feel like to be creative? What does it feel like to understand something? A recent interview with Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, reveals how deeply AI has infiltrated his life and work. Not only does Nadella utilize nearly a dozen different custom-designed AI agents to manage every part of his workflow - from summarizing emails to managing his schedule - but he also uses AI to get through podcasts quickly on his way to work. Instead of actually listening to the podcasts he has transcripts uploaded to an AI assistant who he then chats to about the information while commuting. Why listen to the podcast when you can get the gist through a summary? Why read a book when you can listen to the audio version at X2 speed? Or better yet, watch the movie? Or just read a Wikipedia entry. Or get AI to summarize the wikipedia entry. I'm not here to judge anyone on the way they choose to use technology. Do what you want with ChatGPT. But for a moment consider what you may be skipping over by racing from point A to point B. Sure, you can give ChatGPT a set of increasingly detailed prompts; adding complexity to its summary of a scientific journal or a podcast, but at what point do the prompts get so granular that you may as well read the journal entry itself? If you get generative AI to skim and summarize something, what is it missing? If something was worth being written then surely it is worth being read? If there is a more succinct way to say something then say it more succinctly. In a magnificent article for The New Yorker, Ted Chiang perfectly summed up the deep contradiction at the heart of modern generative AI systems. He argues language, and writing, is fundamentally about communication. If we write an email to someone we can expect the person at the other end to receive those words and consider them with some kind of thought or attention. But modern AI systems (or these simulations of intelligence) are erasing our ability to think, consider, and write. Where does it all end? For Chiang it's pretty dystopian feedback loop of dialectical slop. "We are entering an era where someone might use a large language model to generate a document out of a bulleted list, and send it to a person who will use a large language model to condense that document into a bulleted list. Can anyone seriously argue that this is an improvement?"

[4]

I Talked to the Writer Who Got Caught Publishing ChatGPT-Written Slop. I Get Why He Did It.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily. Over the past week, at least two venerable American newspapers -- the Chicago Sun-Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer -- published a 56-page insert of summer content that was in large part produced by A.I. The most glaring evidence was a now-notorious "summer reading list," which recommended 15 books, five of them real, 10 of them imaginary, with summaries of fake titles like Isabel Allende's Tidewater Dreams, Min Jin Lee's Nightshade Market, Rebecca Makkai's Boiling Point, and Percival Everett's The Rainmakers. The authors exist; the books do not. The rest of the section, which included anodyne listicles about summer activities, barbecuing, and photography, soon attracted additional scrutiny. Dr. Jennifer Campos, a purported professor of leisure studies at the University of Colorado and authority on "hammock culture" on college campuses, did not appear to exist. Other experts cited on summery subjects like gardening and bonfires were similarly difficult to track down, and some real people whose prior remarks were cited did not appear to have said the things attributed to them. It was a sprawling, newspaper-length hallucination of ChatGPT. It's not the first time that a prestigious legacy publication has been caught farming out content to A.I., but for the sheer brazenness of its made-up summer book section, it may have set a new bar. The section was provided to both papers by King Features, a division of the newspaper and magazine giant Hearst that syndicates special sections, comics, puzzles, and so on. Many newspapers have long relied on such collaborations to fill out their pages, whether the syndication is war reports from the Associated Press or Popeye comic strips. In this case, a comms person at Chicago Public Media, which owns the Sun-Times along with local NPR station WBEZ, told 404Media that they don't typically vet those products independently because of their source: "We falsely made the assumption there would be an editorial process for this." The section's sole byline, from a Chicago writer named Marco Buscaglia, appears on nearly a dozen articles. When I spoke to him on the phone on Tuesday morning, Buscaglia was contrite about his mistakes, but not his methods. "I have kind of accepted the fact that if somebody wants 60 pages' worth of stories, there has to be some sort of compromise. But it should be a good compromise. It should be an ethical compromise, and an obvious compromise. And I blew that." Buscaglia's profile is interesting because he's not a tech guy trying to automate journalism jobs. He's a 56-year-old media lifer with two writing degrees trying to automate his own freelance job, using A.I. to maintain an impossible human workload of low-paid gigs. He's the victim of the previous downward spiral of paid writing jobs (thanks to the decline of ad dollars) turned perpetrator of the current downward spiral of paid writing jobs, wielding LLMs to perform a convincing impression of the 25-year-olds who would have crafted the summer heat special section in 1995, and distorting unscrupulous bosses' sense of what they can get for their money. And it was a relatively convincing impression. Buscaglia himself did not know about the errors until Tuesday morning, and the Sun-Times and the Inquirer did not issue any remarks until then. (The Inky's section was published back on May 15.) The A.I. slop of the Heat Index tells us much about the declining standards of print journalism, but it also holds lessons for the current plight of all journalism. Syndication was popular because it allowed local newspapers to get popular comic strips to their subscribers each morning. The better the comics, the more subscribers, and the more subscribers, the more money in advertising -- which, at its peak in 2005, represented more than 80 percent of newspaper revenue. Syndicated games, columnists, and special sections followed in comics' footsteps. The fantastical Heat Index insert comprises the dying embers of this business. In its Chicago Sun-Times edition, there's just one advertisement: for the Goodman Theater's musical of The Color Purple (unlike the articles, the ad was apparently written by a human, and correctly notes the play was inspired by an Alice Walker novel). Ads were sold for human readers, and most readers are now online -- and because the readers are online, an LLM-generated newspaper section persisted for days before someone noticed. This dual audience for the written word -- readers and advertisers -- has survived in digital media, and as with silly summer inserts, it's often the tail of advertising that wags the dog of text. This ad-supported digital ecosystem is the foundation of everything on the internet, news and otherwise, from the business models of Google and Facebook to the popularity of Daily Mail slideshows. Much attention so far has focused on A.I. wranglers like Buscaglia whose offerings can compete with those of human writers and illustrators. But just as important will be the decline in human readers, as web traffic shifts into robot-to-robot conversations. To the extent a source still wants to talk to a journalist, it may be to influence the results of LLM web-trawling -- just as résumés are built by LLMs to be filtered by LLMs, and homework assignments and their grading are simultaneously outsourced to ChatGPT. A feedback loop begins. An early consequence for journalism comes from Google's A.I. Overview, which attempts (and sometimes comically fails) to answer questions on the search results page. Some online publishers say the practice is collapsing traffic to their sites, as searchers never follow through to the source of the information, whether on Slate, Wikipedia, ESPN, or IMDB. Users who ask questions inside an A.I. interface like ChatGPT may never see any other piece of the web at all. And who will buy ads if all that surfing is done by an LLM, not a human? At its developer conference on Tuesday, Google announced it would roll out an "AI Mode" option in every search that will relegate much of today's browsing experience to the back end. The Verge summarizes this shift: Project Mariner, by the way, is a Google A.I. product that performs online transactions, such as buying baseball tickets or ordering groceries. Also on Tuesday, the company announced that Mariner will be available as part of a $250-a-month A.I. subscription plan. In his Stratechery newsletter, Ben Thompson lays out a potential vicious cycle in which a decline in human web traffic prompts a decline in human web creation. The current digital ads ecosystem "depends on humans seeing those webpages, not impersonal agents impervious to advertising, which destroys the economics of ad-supported content sites, which, in the long run, dries up the supply of new content for AI." A.I. can supply answers to questions because it has been trained on countless copyrighted sources of information, which is the subject of ongoing litigation. If it's bad at writing true information, it's because it is also bad at "reading" it. Which brings us back to the Heat Index. If you Google another one of the Heat Index's fake books, The Last Algorithm by Andy Weir, you get an Amazon page for The Last Algorithm by Isaac Asimov -- a Kindle-only product from February fraudulently advertised as a work by the late science-fiction great who died in 1992. If you Google the LLM-hallucinated hammock expert Jennifer Campos, the first result is the Inquirer insert. Fakery is encroaching. In some ways, the Heat Index points to where we're going, toward an internet of regurgitation, in which art and writing are composed of machine-processed fragments of what came before. But the uproar is a sign of something ending -- a last gasp from the era of the diligent, human reader who can tell the difference between a real book and a fake one. Our robot readers are not so discerning.

[5]

Meta stole my book for its AI. Call me a traitor, but I didn't mind

There's one thing worse than having your book stolen. It's not having your book stolen. It's always reassuring when your darkest suspicions about tech billionaires are confirmed. A couple of months back, The Atlantic dropped a bombshell that would have been shocking if we weren't all so jaded. Meta had trained its AI on stolen books. Thousands of them, scanned from LibGen, a massive piracy network of stolen publications. All because Mark Zuckerberg, whose net worth could fund the British Library until the heat death of the universe, had decided that paying authors was a bit steep. The writing community went ballistic, and rightly so. The Society of Authors released a furious statement. Class action lawsuits sprouted like mushrooms after rain. Authors everywhere took to their keyboards; not to create but to check if they'd been robbed. Which is exactly what I did. As I typed my name into The Atlantic's handy search tool, my heart was racing. The result? There it was: my book, Great TED Talks: Creativity: Words of Wisdom from 100 Ted Speakers (HarperCollins, 2021), now unceremoniously fed into Meta's digital maw. I should have been livid, incandescent, ready to join the torch-bearing mob outside Zuckerberg's compound. Instead, I felt...elation. Relief. The joy of validation. I'll have to admit, this was a bit of a shock to me. Apparently, according to my lizard brain, there's one thing worse than having your book stolen. It's not having your book stolen. On further reflection, though, I don't think this is all ego. Before you revoke my author card and banish me from literary festivals for life, hear me out. To put things into context, my books aren't tender coming-of-age novels or lyrical poetry collections. They're reference books: fat, fact-filled tomes designed to inform rather than move the soul. For instance my forthcoming release, The 50 Greatest Designers (Arcturus, out 30 May) is a coffee table book that introduces you to design history's biggest names, from William Morris and Marcel Breuer through to Es Devlin and Pum Lefebure. I'll be honest; a couple of them even I hadn't heard of when I embarked on my research, despite having made a huge impact on designs that are all around us today. Consequently, it's become my passion to share their stores with the world, and although my publishers probably don't want me to say this, I'd rather that happened through AI than not at all. More broadly, if AI is going to exist (which it clearly is, regardless of my feelings on the matter), I'd rather it regurgitated my carefully researched facts than hallucinate absolute bollocks. Because that's what these systems do when they don't have proper training data: they make stuff up with the confidence of a bloke down the pub who's read half an article or watched some dodgy clickbait on YouTube. AI, in practice, will do the same: invent citations, create fictional studies, and generally talk nonsense while sounding eerily authoritative. Which is, I'd argue, exactly how a lot of politicians get elected. So I hope you'll agree there's a twisted logic to my traitorous position. Basically, if someone's going to ask an AI about my subject matter, I'd rather it pull from my work than conjure information from the digital ether. But here's where I draw a thick, uncrossable line: truly creative works. Literature, paintings, songs, films. That kind of AI "training" feels fundamentally different and far more invasive. Reference books are, by design, collections of information presented in a digestible format. The value is in the curation and accuracy, not predominantly in the unique expression. But a novel? A painting? A song? The expression is the entire point. If AI can write a song that sounds like it was penned by Sleater-Kinney, or churn out a passable new Hunger Games novel, that's not "learning", it's stealing. It's copying the essence of an artist's work without the inconvenience of attribution or payment. It's the creative equivalent of identity theft. But just watch. Over the next few years, well-paid tech bros will bang on about "fair use" and "transformative works" while their algorithmic minions hoover up everything creative minds have spent centuries producing. They'll claim the AI is "inspired by" rather than "copying" artistic styles; which is precisely what art students say when they're caught tracing. The irony, of course, is that if all content becomes AI-generated based on existing human work, the machine will eventually start eating its own tail. What happens when there's nothing new to train on except other AI-generated content? It's the cultural equivalent of inbreeding; each generation a bit more warped than the last. But hey, perhaps that's the future we deserve. An endless stream of content that's not quite right, like a cover version of a cover version played by someone who's forgotten their glasses. As long as the share price stays up, eh?

Share

Share

Copy Link

As AI systems become more prevalent, concerns grow about the deteriorating quality of AI-generated content and its impact on information integrity, raising questions about the future of AI technology and its role in various industries.

The Growing Concern of AI Model Collapse

As artificial intelligence (AI) systems become increasingly prevalent in various industries, a new threat looms on the horizon: AI model collapse. This phenomenon, characterized by a gradual loss of accuracy, diversity, and reliability in AI-generated content, is raising alarm bells among experts and users alike

1

.AI model collapse occurs when AI systems, trained on their own outputs, begin to produce increasingly distorted and unreliable information. This process is driven by three main factors: error accumulation, loss of tail data, and feedback loops. As a result, AI models can become "poisoned with their own projection of reality," leading to a significant decline in the quality of their outputs

1

.

Source: The Register

The Impact on Information Integrity

The consequences of AI model collapse are already being felt across various sectors. In the realm of search engines, traditionally reliable platforms are now producing questionable results, especially when it comes to hard data and statistics. This decline in accuracy is particularly concerning for users who rely on these tools for critical information

1

.The journalism industry has also been affected by the unchecked use of AI. A recent incident involving the Chicago Sun-Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer highlighted the dangers of relying too heavily on AI-generated content. Both newspapers published a summer guide insert that contained numerous fabrications, including non-existent books and fake expert quotes, all generated by AI

2

.

Source: Slate

The Ethical Dilemma in Academia and Publishing

The use of AI in academic settings is raising ethical concerns as well. Students are increasingly turning to AI tools like ChatGPT for various tasks, from summarizing complex texts to writing entire essays. This trend is challenging traditional notions of academic integrity and raising questions about the value of human-generated work

3

.In the publishing world, the unauthorized use of copyrighted material to train AI models has sparked controversy. Meta, for instance, was found to have trained its AI on thousands of books scanned from piracy networks, leading to outrage among authors and potential legal repercussions

4

.Related Stories

The Future of AI and Information

As AI technology continues to evolve, the challenge of maintaining information integrity becomes increasingly complex. Some researchers suggest that mixing synthetic data with fresh human-generated content could mitigate the effects of model collapse. However, this approach raises questions about the sourcing and quality of human-generated content in an AI-dominated landscape

1

.

Source: New Atlas

The rise of AI-generated content also poses a threat to the creative industries. While some argue that AI "training" on reference materials may be acceptable, the use of AI to replicate creative works such as literature, art, and music is seen as a form of theft that could potentially stifle human creativity

4

.Conclusion

As we navigate the rapidly evolving landscape of AI technology, it's clear that addressing the challenges of AI model collapse and maintaining information integrity will be crucial. The incidents highlighted in recent news stories serve as a wake-up call for industries relying on AI-generated content, emphasizing the need for robust verification processes and ethical guidelines in AI development and deployment.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

2

Demis Hassabis predicts AGI in 5-8 years, sees new golden era transforming medicine and science

Technology

3

Nvidia and Meta forge massive chip deal as computing power demands reshape AI infrastructure

Technology