AI Hallucinations Plague Legal System as Lawyers and Litigants Embrace Chatbots

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Chatbot dreams generate AI nightmares for Bay Area lawyers

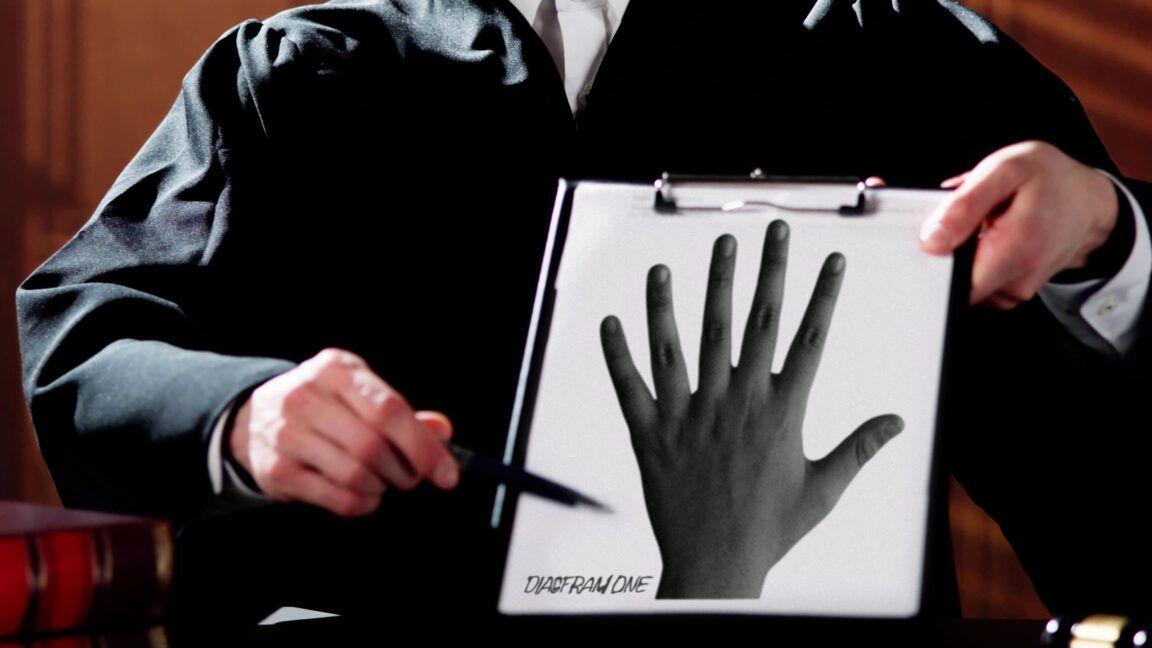

A Palo Alto, California, lawyer with nearly a half-century of experience admitted to an Oakland federal judge this summer that legal cases he referenced in an important court filing didn't actually exist and appeared to be products of artificial intelligence "hallucinations." Jack Russo, in a court filing, described the apparent AI fabrications as a "first-time situation" for him and added, "I am quite embarrassed about it." A specialist in computer law, Russo found himself in the rapidly growing company of lawyers publicly shamed as wildly popular but error-prone artificial intelligence technology like ChatGPT collides with the rigid rules of legal procedure. Hallucinations -- when AI produces inaccurate or nonsensical information -- have posed an ongoing problem in the generative AI that has birthed a Silicon Valley frenzy since San Francisco's OpenAI released its ChatGPT bot in late 2022. In the legal arena, AI-generated errors are drawing heightened scrutiny as lawyers flock to the technology, and irate judges are making referrals to disciplinary authorities and, in dozens of U.S. cases since 2023, levying financial penalties of up to $31,000, including a California-record fine of $10,000 last month in a Southern California case. Chatbots respond to users' prompts by drawing on vast troves of data and use pattern analysis and sophisticated guesswork to produce results. Errors can occur for many reasons, including insufficient or flawed AI-training data or incorrect assumptions by the AI. It affects not just lawyers, but ordinary people seeking information, as when Google's AI overviews last year told users to eat rocks, and add glue to pizza sauce to keep the cheese from sliding off. Russo told Judge Jeffrey White he took full responsibility for not ensuring the filing was factual, but said a long recovery from COVID-19 at an age beyond 70 led him to delegate tasks to support staff without "adequate supervision protocols" in place. "No sympathy here," internet law professor Eric Goldman of Santa Clara University said. "Every lawyer can tell a sob story, but I'm not falling for it. We have rules that require lawyers to double-check what they file." The judge wrote in a court order last month that Russo's AI-dreamed fabrications were a first for him, too. Russo broke a federal court rule by failing to adequately check his motion to throw out a contract dispute case, White wrote. The court, the judge sniped, "has been required to divert its attention from the merits of this and other cases to address this issue." White issued a preliminary order requiring Russo to pay some of the opposing side's legal fees. Russo told White his firm, Computerlaw Group, had "taken steps to fix and prevent a reoccurrence." Russo declined to answer questions from this news organization. As recently as mid-2023, it was a novelty to find a lawyer facing a reprimand for submitting court filings referring to nonexistent cases conjured up by artificial intelligence, but now such incidents arise nearly by the day, and even judges have been implicated, according to a database compiled by Damien Charlotin, a senior fellow at French business school HEC Paris who is tracking worldwide legal filings containing AI hallucinations. "I think the acceleration is still ongoing," Charlotin said. Charlotin said his database includes "a surprising number" of lawyers who are sloppy, reckless or "plain bad." In May, San Francisco lawyer Ivana Dukanovic admitted in the U.S. District Court in San Jose to an "embarrassing and unintentional mistake" by herself and others at legal firm Latham & Watkins. While representing San Francisco AI giant Anthropic in a music copyright case, they submitted a filing with hallucinated material, Dukanovic wrote. Dukanovic -- whose company bio lists "artificial intelligence" as one of her areas of legal practice -- blamed the creation of the false information on a particular chatbot: Claude.ai, the flagship product of her client Anthropic. Judge Susan van Keulen ordered part of the filing removed from the court record. Dukanovic, who, along with her firm, appears to have dodged sanctions, did not respond to requests for comment. Charlotin has found 113 U.S. cases involving lawyers submitting filings with hallucinated material, mostly legal-case citations, that have been the subject of court decisions since mid-2023. He believes many court submissions with AI fabrications are never caught, potentially affecting case outcomes. Court decisions can have "life-changing consequences," including in matters involving child custody or disability claims, law professor Goldman said. "The stakes in some cases are so high, and if someone is distorting the judge's decision-making, the system breaks down," Goldman said. Still, AI can be a useful tool for lawyers, finding information people might miss, and helping to prepare documents, he said. "If people use AI wisely, it helps them do a better job," Goldman said. "That's pushing everyone to adopt it." Survey results released in April by the American Bar Association, the nation's largest lawyers group, found that AI use by law firms almost tripled last year to 30% of responding law offices from 11% in 2023, and that ChatGPT was the "clear leader across firms of every size." Fines may be the least of a lawyer's worries, Goldman said. A judge could flag an attorney to their licensing organization for discipline, or dismiss a case, or reject a key filing, or view everything the lawyer does in the case with skepticism. A client could sue for malpractice. Orders to pay the other side's legal fees can require six-figure payments. Charlotin's database shows judges slapping many lawyers with warnings or referrals to disciplinary authorities, and sometimes purging all or part of a filing from the court record, or ordering payment of the opposition's fees. Last year, a federal appeals court in California threw out an appeal it said was "replete with misrepresentations and fabricated case law," including "two cases that do not appear to exist." Charlotin expects his database to keep swelling. "I don't really see it decrease on the expected lines of 'surely everyone should know by now,'" Charlotin said. #YR@ MediaNews Group, Inc. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

[2]

These people ditched lawyers for ChatGPT in court

Even as some litigants have found success in small-claims disputes, legal professionals who spoke to NBC News say AI-drafted court documents are often littered with inaccuracies and faulty reasoning. Holmes said litigants "will use a case that ChatGPT gave them, and when I go to look it up, it does not exist. Most of the time, we get them dismissed for failure to state an actual claim, because a lot of times it's just kind of, not to be rude, but nonsense." AI models often generate information that is false or misleading but presented as fact, a phenomenon known as "hallucination." Chatbots are trained on vast datasets to predict the most likely response to a query but sometimes encounter gaps in their knowledge. In these cases, the model may attempt to fill in the missing pieces with its best approximation, which can result in inaccurate or fabricated details. For litigants, AI hallucinations can lead to pricey penalties. Jack Owoc, a colorful Florida-based energy drink mogul who lost a false advertising case to the tune of $311 million and is now representing himself, was recently sanctioned for filing a court motion with 11 AI-hallucinated citations referencing court cases that do not exist. Owoc admitted he had used generative AI to draft the document due to his limited finances. He was ordered to complete 10 hours of community service and is now required to disclose whether he uses AI in all future filings in the case. "Just like a law firm would have to check the work of a junior associate, so do you have to check the work generated by AI," Owoc said via email. Holmes and other legal professionals say there are common telltale signs of careless AI use, such as citations to nonexistent case law, filler language that was left in, and ChatGPT-style emoji or formatting that looks nothing like a typical legal document. Damien Charlotin, a legal researcher and data scientist, has organized a public database tracking legal decisions in cases where litigants were caught using AI in court. He's documented 282 such cases in the U.S. and more than 130 from other countries dating back to 2023. "It really started to accelerate around the spring of 2025," Charlotin said. And the database is far from exhaustive. It only tracks cases where the established or alleged use of AI was directly addressed by the court, and Charlotin said most of its entries are referred to him by lawyers or other researchers. He noted that there are generally three types of AI hallucinations: "You got the fabricated case law, and that's quite easy to spot, because the case does not exist. Then you got the false quotations from existing case law. That's also rather easy to spot because you do control-F," Charlotin said. "And then there is misrepresented case law. That's much harder, because you're citing something that exists but you're totally misrepresenting it." Earl Takefman has experienced AI's hallucinatory tendencies firsthand. He is currently representing himself in several cases in Florida regarding a pickleball business deal gone awry and started using AI to help him in court last year. "It never for a second even crossed my mind that ChatGPT would totally make up cases, and unfortunately, I found out the hard way," Takefman told NBC News. Takefman realized his mistake when the opposing counsel pointed out a hallucinated case in one of Takefman's filings. "I went back to ChatGPT and told it that it really f----d me over," he said. "It apologized." A judge admonished Takefman for citing the same nonexistent case -- an imaginary one from 1995 called Hernandez v. Gilbert -- in two separate filings, among other missteps, according to court documents. Embarrassed about the oversight, Takefman resolved to be more careful. "So I said, 'OK, I know how to get around it. I'm going to ask ChatGPT to give me actual quotations from the court case I want to reference. Surely they would never make up an actual quotation.' And it turns out they were making that up too!" "I certainly did not intend to mislead the court," Takefman said. "They take it very, very seriously and don't let you off the hook because you're a pro se litigant." In late August, the court forced Takefman to explain why he should not receive sanctions given his mistakes. The court accepted Takefman's apology and did not apply sanctions. The experience has not turned off Takefman from using AI in his court dealings. "Now, I check between different applications, so I'll take what Grok gives me and give it to ChatGPT and see if it agrees -- that all the cases are real, that there aren't any hallucinations, and that the cases actually mean what the AI thinks they mean," Takefman said. "Then, I put all of the cases into Google to do one last check to make sure that the cases are real. That way, I can actually say to a judge that I checked the case and it exists," Takefman said. So far, the majority of AI hallucinations in Charlotin's database come from pro se litigants, but many have also come from lawyers themselves. Earlier this month, a California court ordered an attorney to pay a $10,000 fine for filing a state court appeal in which 21 of the 23 quotes from cited cases were hallucinated by ChatGPT. It appears to be the largest-ever fine issued over AI fabrications, according to CalMatters. "I can understand more easily how someone without a lawyer, and maybe who feels like they don't have the money to access an attorney, would be tempted to rely on one of these tools," said Robert Freund, an attorney who regularly contributes to Charlotin's database. "What I can't understand is an attorney betraying the most fundamental parts of our responsibilities to our clients ... and making these arguments that are based on total fabrication." Freund, who runs a law firm in Los Angeles, said the influx of AI hallucinations wastes both the court's and the opposing party's time by forcing them to use up resources identifying factual inaccuracies. Even after a judge admonishes someone caught filing AI slop, sometimes the same plaintiff continues to flood the court with AI-generated filings "filled with junk." Matthew Garces, a registered nurse in New Mexico who's a strong proponent of using AI to represent himself in legal matters, is currently involved in 28 federal civil suits, including 10 active appeals and several petitions to the Supreme Court. These cases cover a range of topics, including medical malpractice, housing disputes between Garces and his landlord, and alleged improper judicial conduct toward Garces. After noting that Garces submitted documents referencing numerous nonexistent cases, a panel of judges from the 5th U.S. Court of Appeals recently criticized Garces' prolific filing of new cases, writing that he is "WARNED FOR A SECOND TIME" to avoid any "future frivolous, repetitive, or otherwise abusive filings" or risk increasingly severe penalties. A magistrate judge in another of Garces' cases also recommended that he be banned from filing any lawsuits without the express authorization of a more senior judge, and that Garces be classified as "a vexatious litigant." Still, Garces told NBC News that "AI provides access to the courthouse doors that money often keeps closed. Managing nearly 30 federal suits on my own would be nearly impossible without AI tools to organize, research and prepare filings." As the use of AI in court grows, some pro bono legal clinics are now trying to teach their self-representing clients to use AI in ways that help rather than harm them -- without offering direct legal advice. "This is the most exciting time to be a lawyer," said Zoe Dolan, a supervising attorney at Public Counsel, a nonprofit public interest law firm and legal advocacy center in Los Angeles. "The amount of impact that any one advocate can now have is only sort of limited by our imagination and organizational structures." Last year, Dolan helped create a class for self-represented litigants in Los Angeles County to learn how to leverage AI in their cases. The class taught participants how to use various prompts to create documents, how to fact-check the AI systems' outputs and how to use chatbots to verify other chatbots' work. Several of the litigants who took the class, including White, have gone on to win their cases while using AI. Numerous legal professionals railing against the sloppy use of AI in court also say that they're not opposed to the use of AI among lawyers more generally. In fact, many say they feel optimistic about AI adoption by legal professionals who have the expertise to analyze and verify its outputs. Andrew Montez, an attorney in Southern California, said that despite his firm "seeing pro se litigants constantly using AI" over the past six months, he himself has found AI tools useful as a starting point for research or brainstorming. He said he never inputs real client names or confidential information, and he checks every citation manually. While AI cannot substitute for his own legal research and analysis, Montez said, these systems enable lawyers to write better-researched briefs more quickly. "Going forward in the legal profession, all attorneys will have to use AI in some way or another. Otherwise they will be outgunned," Montez said. "AI is the great equalizer. Internet research, to a certain extent, made law libraries obsolete. I think AI is really the next frontier." As for pro se litigants without legal expertise, Montez said he believes most cases are too complex for AI alone to understand sufficient context and provide good enough analysis to help someone succeed in court. But he noted that he could envision a future in which more people will use AI to successfully represent themselves, especially in small claims courts. White, who avoided eviction this year with the help of ChatGPT and Perplexity.ai, said she views AI as a way to level the playing field. When asked what advice she would give to other pro se litigants, she thought it was fitting to craft a reply with ChatGPT.

Share

Share

Copy Link

The increasing use of AI in legal proceedings has led to a surge in 'hallucinations' - fabricated information presented as fact. This trend is causing concern among legal professionals and judges, resulting in sanctions and penalties for those who submit AI-generated falsehoods in court.

The Rise of AI in Legal Proceedings

The legal world is grappling with a new challenge as artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT increasingly find their way into courtrooms. Lawyers and self-represented litigants are turning to AI for assistance in drafting legal documents, but this trend has led to a surge in 'hallucinations' - fabricated information presented as fact in court filings

1

2

.AI Hallucinations: A Growing Concern

AI hallucinations occur when chatbots produce inaccurate or nonsensical information, often due to gaps in their knowledge or flaws in their training data. In the legal context, these hallucinations typically manifest as:

- Citations to nonexistent case law

- False quotations from existing cases

- Misrepresentation of actual case law

Damien Charlotin, a legal researcher and data scientist, has documented 282 cases in the U.S. and over 130 internationally where litigants were caught using AI in court since 2023

2

.Consequences and Judicial Response

The submission of AI-generated falsehoods in court has drawn the ire of judges, leading to severe consequences:

- Financial penalties of up to $31,000, with a California-record fine of $10,000 in a recent case

1

- Referrals to disciplinary authorities

- Court orders to complete community service

- Requirements to disclose AI use in future filings

Notable Incidents

Several high-profile cases have highlighted the dangers of unchecked AI use in legal proceedings:

- Jack Russo, a Palo Alto lawyer with nearly 50 years of experience, admitted to using AI-generated cases in an important court filing

1

- Ivana Dukanovic, representing AI giant Anthropic, submitted a filing with hallucinated material generated by the company's own AI, Claude.ai

1

- Jack Owoc, a Florida-based energy drink mogul, was sanctioned for filing a motion with 11 AI-hallucinated citations

2

Related Stories

Strategies for Responsible AI Use

As the legal community grapples with this issue, some practitioners are developing strategies to mitigate the risks of AI hallucinations:

- Cross-checking AI-generated information across multiple platforms

- Verifying case law citations through traditional legal research methods

- Implementing stricter supervision protocols for AI-assisted work

The Future of AI in Law

Despite the challenges, many legal professionals believe AI can be a valuable tool when used responsibly. Eric Goldman, an internet law professor at Santa Clara University, suggests that AI can help lawyers find information and prepare documents more efficiently if used wisely

1

.As the legal system adapts to this new technology, the focus will likely shift towards developing best practices for AI integration and enhancing the ability to detect and prevent AI-generated errors in court filings.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

Related Stories

AI-Generated Legal Citations Lead to $10,000 Fine for California Attorney

22 Sept 2025•Technology

AI Hallucinations Plague Legal Profession as Lawyers Face Mounting Sanctions for ChatGPT Misuse

09 Nov 2025•Policy and Regulation

AI Hallucinations in Legal Filings: A Growing Concern for US Courts

22 Jul 2025•Policy and Regulation

Recent Highlights

1

Google Maps unveils Ask Maps with Gemini AI and 3D Immersive Navigation in biggest update

Technology

2

AI chatbots help plan violent attacks as safety guardrails fail, new investigation reveals

Technology

3

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round as questions swirl around AI bubble and profitability

Business and Economy