AI Reveals Alarming Glacier Loss in Arctic's Svalbard Archipelago

3 Sources

3 Sources

[1]

We built an AI model that analysed millions of images of retreating glaciers - what it found is alarming

University of Bristol provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average since 1979. Svalbard, an archipelago near the northeast coast of Greenland, is at the frontline of this climate change, warming up to seven times faster than the rest of the world. More than half of Svalbard is covered by glaciers. If they were to completely melt tomorrow, the global sea level would rise by 1.7cm. Although this won't happen overnight, glaciers in the Arctic are highly sensitive to even slight temperature increases. To better understand glaciers in Svalbard and beyond, we used an AI model to analyse millions of satellite images from Svalbard over the past four decades. Our research is now published in Nature Communications, and shows these glaciers are shrinking faster than ever, in line with global warming. Specifically, we looked at glaciers that drain directly into the ocean, what are known as "marine-terminating glaciers". Most of Svalbard's glaciers fit this category. They act as an ecological pump in the fjords they flow into by transferring nutrient-rich seawater to the ocean surface and can even change patterns of ocean circulation. Where these glaciers meet the sea, they mainly lose mass through iceberg calving, a process in which large chunks of ice detach from the glacier and fall into the ocean. Understanding this process is key to accurately predicting future glacier mass loss, because calving can result in faster ice flow within the glacier and ultimately into the sea. Despite its importance, understanding the glacier calving process has been a longstanding challenge in glaciology, as this process is difficult to observe, let alone accurately model. However, we can use the past to help us understand the future. AI replaces painstaking human labour When mapping the glacier calving front - the boundary between ice and ocean - traditionally human researchers painstakingly look through satellite imagery and make digital records. This process is highly labour-intensive, inefficient and particularly unreproducible as different people can spot different things even in the same satellite image. Given the number of satellite images available nowadays, we may not have the human resources to map every region for every year. A novel way to tackle this problem is by using automated methods like artificial intelligence (AI), which can quickly identify glacier patterns across large areas. This is what we did in our new study, using AI to analyse millions of satellite images of 149 marine-terminating glaciers taken between 1985 and 2023. This meant we could examine the glacier retreats at unprecedented scale and scope. Insights from 1985 to today We found that the vast majority (91%) of marine-terminating glaciers across Svalbard have been shrinking significantly. We discovered a loss of more than 800km² of glacier since 1985, larger than the area of New York City, and equivalent to an annual loss of 24km² a year, almost twice the size of Heathrow airport in London. The biggest spike was detected in 2016, when the calving rates doubled in response to periods of extreme warming. That year, Svalbard also had its wettest summer and autumn since 1955, including a record 42mm of rain in a single day in October. This was accompanied by unusually warm and ice-free seas. How ocean warming triggers glacier calving In addition to the long-term retreat, these glaciers also retreat in the summer and advance again in winter, often by several hundred metres. This can be greater than the changes from year to year. We found that 62% of the glaciers in Svalbard experience these seasonal cycles. While this phenomenon is well documented across Greenland, it had previously only been observed for a handful of glaciers in Svalbard, primarily through manual digitisation. We then compared these seasonal changes with seasonal variations in air and ocean temperature. We found that as the ocean warmed up in spring, the glacier retreated almost immediately. This was a nice demonstration of something scientists had long suspected: the seasonal ebbs and flows of these glaciers are caused by changes in ocean temperatures. A global threat Svalbard experiences frequent climate extremes due to its unique location in the Arctic yet close to the warm Atlantic water. Our findings indicate that marine-terminating glaciers are highly sensitive to climate extremes and the biggest retreat rates have occurred in recent years. This same type of glaciers can be found across the Arctic and, in particular, around Greenland, the largest ice mass in the northern hemisphere. What happens to glaciers in Svalbard is likely to be repeated elsewhere. If the current climate warming trend continues, these glaciers will retreat more rapidly, the sea level will rise, and millions of people in coastal areas worldwide will be endangered. Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like? Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 40,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

[2]

Pioneering research exposes huge loss of glaciers in one of the fastest-warming places on Earth

A new study has revealed the alarming extent glaciers have shrunk over the past 40 years in a global warming hotspot for the first time -- and the biggest retreat has occurred in recent years. The research, led by the University of Bristol and published in Nature Communications, shows the vast majority (91%) of glaciers across Svalbard in the Arctic have been significantly shrinking. Findings revealed an area loss of more than 800 kmat the glacier margins in this Norwegian group of islands since 1985. The study also found that more than half of the glaciers (62%) undergo seasonal cycles in glacier calving -- when large chunks of ice break away due to higher ocean and air temperatures. Lead author Dr Tian Li, Senior Research Associate at the University's Glaciology Centre, said: "The scale of glacier retreats over the past few decades is astonishing, almost covering the entire Svalbard. This highlights the vulnerability of glaciers to climate change, especially in Svalbard, a region experiencing rapid warming up to seven times faster than the global average." The research team deployed Artificial Intelligence (AI) to quickly identify glacier patterns across large areas. Using a novel AI model, they analysed millions of satellite images capturing the end positions of glaciers across the entire Svalbard. The findings provide an unprecedented level of detail into the scale and nature of glacier loss in this region. The biggest spike in glacier retreats was detected in 2016, when the calving rates were double the average between 2010 and 2015, in response to extreme warming events. "This was likely caused by a large-scale weather pattern called atmospheric blocking that can influence atmospheric pressures," Dr Li said. "With the increasing frequency of atmospheric blocking and ongoing regional warming, future retreats of glaciers are expected to accelerate, resulting in greater glacier mass loss. This would change the ocean circulation and marine life environments in the Arctic." Svalbard is one of the fastest-warming places on Earth. The low altitude of the archipelago's ice fields and geographical location in the high North Atlantic make it especially sensitive to climate change. Co-author Jonathan Bamber, Professor of Glaciology at the University of Bristol, said: "Glacier calving is a poorly modelled and understood process that plays a crucial role in the health of a glacier. Our study provides valuable insights into what controls calving and how it responds to climate forcing in an area at the frontline of global warming."

[3]

Pioneering research exposes huge loss of glaciers in one of the fastest-warming places on Earth | Newswise

This figure shows the glacier front retreat rates between 1985 and 2023. The larger darker red circles indicate areas of greatest glacier loss. A new study has revealed the alarming extent glaciers have shrunk over the past 40 years in a global warming hotspot for the first time - and the biggest retreat has occurred in recent years. The research, led by the University of Bristol and published in Nature Communications, shows the vast majority (91%) of glaciers across Svalbard in the Arctic have been significantly shrinking. Findings revealed an area loss of more than 800 kmat the glacier margins in this Norwegian group of islands since 1985. The study also found that more than half of the glaciers (62%) undergo seasonal cycles in glacier calving - when large chunks of ice break away due to higher ocean and air temperatures. Lead author Dr Tian Li, Senior Research Associate at the University's Glaciology Centre, said: "The scale of glacier retreats over the past few decades is astonishing, almost covering the entire Svalbard. This highlights the vulnerability of glaciers to climate change, especially in Svalbard, a region experiencing rapid warming up to seven times faster than the global average." The research team deployed Artificial Intelligence (AI) to quickly identify glacier patterns across large areas. Using a novel AI model, they analysed millions of satellite images capturing the end positions of glaciers across the entire Svalbard. The findings provide an unprecedented level of detail into the scale and nature of glacier loss in this region. The biggest spike in glacier retreats was detected in 2016, when the calving rates were double the average between 2010 and 2015, in response to extreme warming events. "This was likely caused by a large-scale weather pattern called atmospheric blocking that can influence atmospheric pressures," Dr Li said. "With the increasing frequency of atmospheric blocking and ongoing regional warming, future retreats of glaciers are expected to accelerate, resulting in greater glacier mass loss. This would change the ocean circulation and marine life environments in the Arctic." Svalbard is one of the fastest-warming places on Earth. The low altitude of the archipelago's ice fields and geographical location in the high North Atlantic make it especially sensitive to climate change. Co-author Jonathan Bamber, Professor of Glaciology at the University of Bristol, said: "Glacier calving is a poorly modelled and understood process that plays a crucial role in the health of a glacier. Our study provides valuable insights into what controls calving and how it responds to climate forcing in an area at the frontline of global warming."

Share

Share

Copy Link

A groundbreaking study using AI to analyze satellite imagery has uncovered significant glacier shrinkage in Svalbard, one of the fastest-warming regions on Earth, over the past four decades.

AI-Powered Study Reveals Unprecedented Glacier Loss in Svalbard

A groundbreaking study led by the University of Bristol has employed artificial intelligence to analyze millions of satellite images, revealing alarming glacier loss in Svalbard, an Arctic archipelago experiencing rapid warming. The research, published in Nature Communications, provides unprecedented insights into the scale and nature of glacier retreat in one of Earth's fastest-warming regions

1

.Significant Glacier Shrinkage and Area Loss

The study found that 91% of marine-terminating glaciers across Svalbard have been significantly shrinking. Since 1985, more than 800 km² of glacier area has been lost, equivalent to an area larger than New York City. This translates to an annual loss of 24 km², almost twice the size of London's Heathrow airport

2

.AI's Role in Glacier Analysis

Researchers deployed a novel AI model to analyze millions of satellite images capturing glacier end positions across Svalbard. This innovative approach allowed for quick identification of glacier patterns across large areas, providing an unprecedented level of detail into the scale and nature of glacier loss

3

.Seasonal Cycles and Extreme Events

The study revealed that 62% of Svalbard's glaciers undergo seasonal cycles in glacier calving, a process where large ice chunks break away due to higher ocean and air temperatures. While this phenomenon was previously well-documented in Greenland, it had only been observed in a handful of Svalbard glaciers through manual digitization

1

.2016: A Year of Extreme Retreat

The most significant spike in glacier retreats was detected in 2016 when calving rates doubled compared to the 2010-2015 average. This extreme event coincided with Svalbard's wettest summer and autumn since 1955, including a record 42mm of rain in a single October day. The unusual warmth and ice-free seas likely contributed to this accelerated retreat

1

.Related Stories

Climate Change Implications

Svalbard is warming up to seven times faster than the global average, making it particularly vulnerable to climate change. The study's lead author, Dr. Tian Li, emphasized that the scale of glacier retreats over the past few decades is "astonishing" and highlights the vulnerability of glaciers to climate change

2

.Future Projections and Global Impact

With the increasing frequency of atmospheric blocking and ongoing regional warming, future glacier retreats are expected to accelerate. This could result in greater glacier mass loss, potentially altering ocean circulation and marine life environments in the Arctic. The findings from Svalbard may be indicative of what could happen to similar glaciers across the Arctic, particularly around Greenland

1

3

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[2]

Related Stories

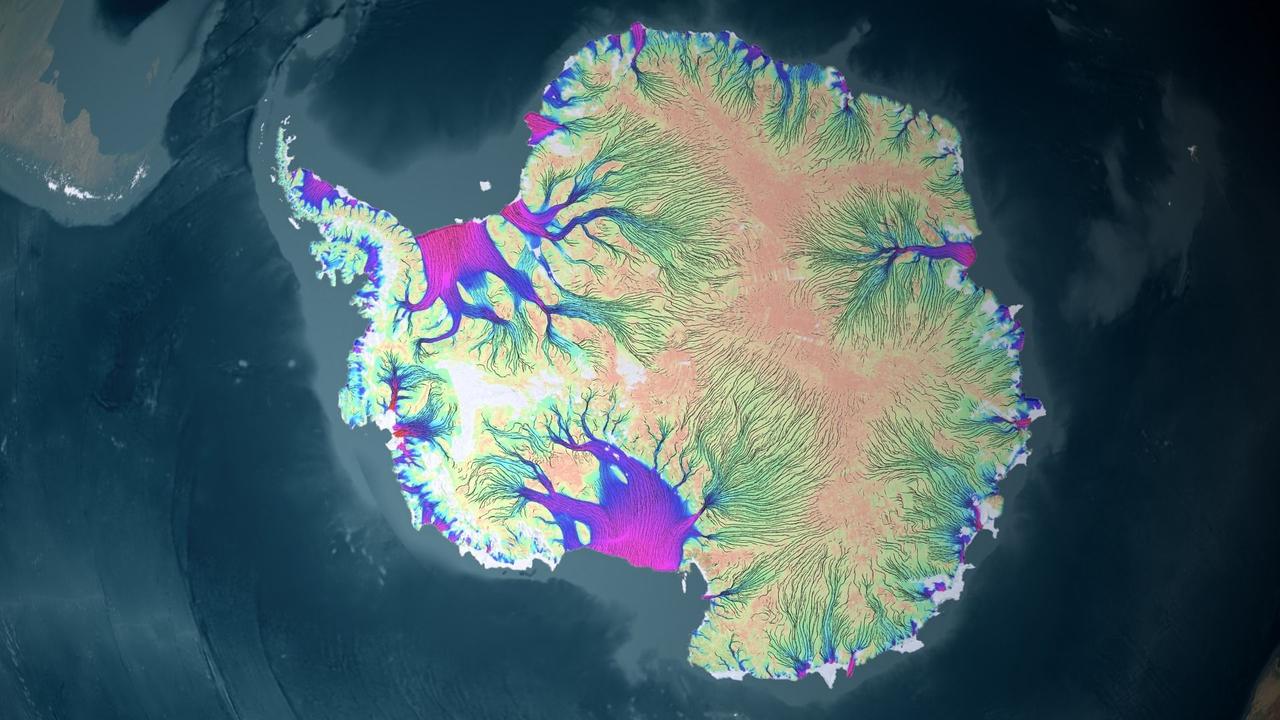

AI Reveals New Insights into Antarctic Ice Flow, Challenging Existing Climate Models

15 Mar 2025•Science and Research

AI Predicts Faster Global Warming, Surpassing Critical Thresholds

11 Dec 2024•Science and Research

AI and Space Lasers Revolutionize Forest Carbon Mapping for Climate Science

15 Jun 2025•Science and Research

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic sues Pentagon over supply chain risk label after refusing autonomous weapons use

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round as questions swirl around AI bubble and profitability

Business and Economy