AI's Energy Dilemma: Data Centers Turn to Unconventional Power Sources Amid Surging Demand

9 Sources

9 Sources

[1]

Your AI tools run on fracked gas and bulldozed Texas land | TechCrunch

The AI era is giving fracking a second act, a surprising twist for an industry that, even during its early 2010s boom years, was blamed by climate advocates for poisoned water tables, man-made earthquakes, and the stubborn persistence of fossil fuels. AI companies are building massive data centers near major gas-production sites, often generating their own power by tapping directly into fossil fuels. It's a trend that's been overshadowed by headlines about the intersection of AI and healthcare (and solving climate change), but it's one that could reshape -- and raise difficult questions for -- the communities that host these facilities. Take the latest example. This week, the Wall Street Journal reported that AI coding assistant startup Poolside is constructing a data center complex on more than 500 acres in West Texas -- about 300 miles west of Dallas -- a footprint two-thirds the size of Central Park. The facility will generate its own power by tapping natural gas from the Permian Basin, the nation's most productive oil and gas field, where hydraulic fracturing isn't just common but really the only game in town. The project, dubbed Horizon, will produce two gigawatts of computing power. That's equivalent to the Hoover Dam's entire electric capacity, except instead of harnessing the Colorado River, it's burning fracked gas. Poolside is developing the facility with CoreWeave, a cloud computing company that rents out access to Nvidia AI chips and that's supplying access to more than 40,000 of them. The Journal calls it an "energy Wild West," which seems apt. Yet Poolside is far from alone. Nearly all the major AI players are pursuing similar strategies. Last month, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman toured his company's flagship Stargate data center in Abilene, Texas -- around 200 miles from the Permian Basin -- where he was candid, saying, "We're burning gas to run this data center." The complex requires about 900 megawatts of electricity across eight buildings and includes a new gas-fired power plant using turbines similar to those that power warships, according to the Associated Press. The companies say the plant provides only backup power, with most electricity coming from the local grid. That grid, for the record, draws from a mix of natural gas and the sprawling wind and solar farms in West Texas. But the people living near these projects aren't exactly comforted. Arlene Mendler lives across the street from Stargate. She told the AP she wishes someone had asked her opinion before bulldozers eliminated a huge tract of mesquite shrubland to make room for what's being built atop it. "It has completely changed the way we were living," Mendler told the AP. She moved to the area 33 years ago seeking "peace, quiet, tranquility." Now construction is the soundtrack in the background, and bright lights on the scene have spoiled her nighttime views. Then there's the water. In drought-prone West Texas, locals are particularly nervous about how new data centers will impact the water supply. The city's reservoirs were at roughly half-capacity during Altman's visit, with residents on a twice-weekly outdoor watering schedule. Oracle claims each of the eight buildings will need just 12,000 gallons per year after an initial million-gallon fill for closed-loop cooling systems. But Shaolei Ren, a University of California, Riverside professor who studies AI's environmental footprint, told the AP that's misleading. These systems require more electricity, which means more indirect water consumption at the power plants generating that electricity. Meta is pursuing a similar strategy. In Richland Parish, the poorest region of Louisiana, the company plans to build a $10 billion data center the size of 1,700 football fields that will require two gigawatts of power for computation alone. Utility company Entergy will spend $3.2 billion to build three large natural-gas power plants with 2.3 gigawatts of capacity to feed the facility by burning gas extracted through fracking in the nearby Haynesville Shale. Louisiana residents, like those in Abilene, aren't thrilled to be encircled by bulldozers around the clock. (Meta is also building in Texas, though elsewhere in the state. This week the company announced a $1.5 billion data center in El Paso, near the New Mexico border, with one gigawatt of capacity expected online in 2028. El Paso isn't near the Permian Basin, and Meta says the facility will be matched with 100% clean and renewable energy. One point for Meta.) Even Elon Musk's xAI, whose Memphis facility has generated considerable controversy this year, has fracking connections. Memphis Light, Gas and Water - which currently sells power to xAI but will eventually own the substations xAI is building - purchases natural gas on the spot market and pipes it to Memphis via two companies: Texas Gas Transmission Corp. and Trunkline Gas Company. Texas Gas Transmission is a bidirectional pipeline carrying natural gas from Gulf Coast supply areas and several major hydraulically fractured shale formations through Arkansas, Mississippi, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Trunkline Gas Company, the other Memphis supplier, also carries natural gas from fracked sources. If you're wondering why AI companies are pursuing this path, they'll tell you it's not just about electricity; it's also about beating China. That was the argument Chris Lehane made last week. Lehane, a veteran political operative who joined OpenAI as vice president of global affairs in 2024, laid out the case during an on-stage interview with TechCrunch. "We believe that in the not-too-distant future, at least in the U.S., and really around the world, we are going to need to be generating in the neighborhood of a gigawatt of energy a week," Lehane said. He pointed to China's massive energy buildout: 450 gigawatts and 33 nuclear facilities constructed in the last year alone. When TechCrunch asked about Stargate's decision to build in economically challenged areas like Abilene, or Lordstown, Ohio, where more gas-powered plants are planned, Lehane returned to geopolitics. "If we [as a country] do this right, you have an opportunity to re-industrialize countries, bring manufacturing back and also transition our energy systems so that we do the modernization that needs to take place." The Trump administration is certainly on board. The July 2025 executive order fast-tracks gas-powered AI data centers by streamlining environmental permits, offering financial incentives, and opening federal lands for projects using natural gas, coal, or nuclear power -- while explicitly excluding renewables from support. For now, most AI users remain largely unaware of the carbon footprint behind their dazzling new toys and work tools. They're more focused on capabilities like Sora 2 - OpenAI's hyperrealistic video-generation product that requires exponentially more energy than a simple chatbot - than on where the electricity comes from. The companies are counting on this. They've positioned natural gas as the pragmatic, inevitable answer to AI's exploding power demands. But the speed and scale of this fossil fuel buildout deserves more attention than it's getting. If this is a bubble, it won't be pretty. The AI sector has become a circular firing squad of dependencies: OpenAI needs Microsoft needs Nvidia needs Broadcom needs Oracle needs data center operators who need OpenAI. They're all buying from and selling to each other in a self-reinforcing loop. The Financial Times noted this week if the foundation cracks, there'll be a lot of expensive infrastructure left standing around, both the digital and the gas-burning kind. OpenAI's ability alone to meet its obligations is "increasingly a concern for the wider economy," the outlet wrote. One key question that's been largely absent from the conversation is whether all this new capacity is even necessary. A Duke University study found that utilities typically use only 53% of their available capacity throughout the year. That suggests significant room to accommodate new demand without constructing new power plants, as MIT Technology Review reported earlier this year. The Duke researchers estimate that if data centers reduced electricity consumption by roughly half for just a few hours during annual peak demand periods, utilities could handle an additional 76 gigawatts of new load. That would effectively absorb the 65 gigawatts data centers are projected to need by 2029. That kind of flexibility would allow companies to launch AI data centers faster. More importantly, it could provide a reprieve from the rush to build natural gas infrastructure, giving utilities time to develop cleaner alternatives. But again, that would mean losing ground to an autocratic regime, per Lehane and many others in the industry, so instead, the natural gas building spree appears likely to saddle regions with more fossil-fuel plants and leave residents with soaring electricity bills to finance today's investments, including long after the tech companies' contracts expire. Meta, for instance, has guaranteed it will cover Entergy's costs for the new Louisiana generation for 15 years. Poolside's lease with CoreWeave runs for 15 years. What happens to customers when those contracts end remains an open question. Things may eventually change. A lot of private money is being funneled into small modular reactors and solar installations with the expectation that these cleaner energy alternatives will become more central energy sources for these data centers. Fusion startups like Helion and Commonwealth Fusion Systems have similarly raised substantial funding from those the front lines of AI, including Nvidia and Altman. This optimism isn't confined to private investment circles. The excitement has spilled over into public markets, where several "non-revenue-generating" energy companies that have managed to go public have truly anticipatory, market caps, based on the expectation that they will one day fuel these data centers. In the meantime -- which could still be decades -- the most pressing concern is that the people who'll be left holding the bag, financially and environmentally, never asked for any of this in the first place.

[2]

Data centers turn to commercial aircraft jet engines bolted onto trailers as AI power crunch bites -- cast-off turbines generate up to 48 MW of electricity apiece

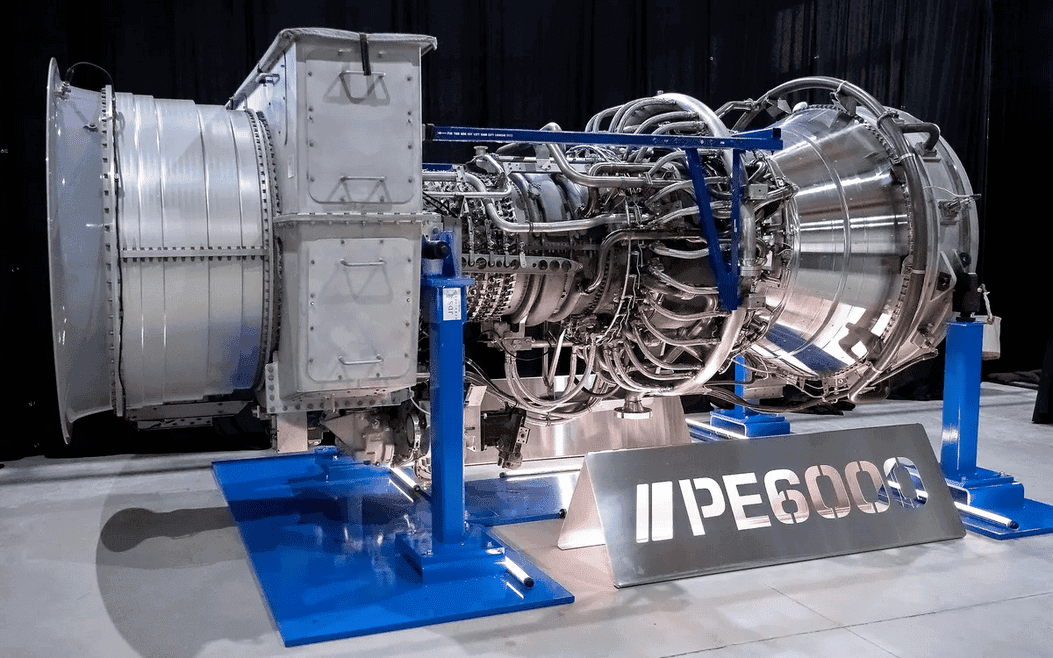

With AI buildouts outpacing the grid, data centers are rolling in jet-powered turbines to keep their clusters online. Faced with multi-year delays to secure grid power, US data center operators are deploying aeroderivative gas turbines -- effectively retired commercial aircraft engines bolted into trailers -- to keep AI infrastructure online. According to IEEE Spectrum, facilities in Texas are already spinning up units based on General Electric's CF6-80C2 and LM6000, the same turbine cores once found on 767s and Airbus A310s. Vendors like ProEnergy and Mitsubishi Power have turned these into modular, fast-start generators capable of delivering 48 megawatts apiece, enough to support a large AI cluster while utility-scale infrastructure lags. Fast, loud, and anything but elegant, these "bridging power" units come from vendors like ProEnergy, which offers trailerized turbines built around ex-aviation cores that can spin up in minutes to meet energy demand. Meanwhile, Mitsubishi Power's FT8 MOBILEPAC, which derives from Pratt & Whitney jet engines, delivers a similar output in a self-contained footprint designed for fast deployment. While this might not be the cheapest, and certainly not the cleanest, way to power racks, it's a viable stopgap for companies racing to hit AI milestones while local substations and modular nuclear power deployments remain years away. Jet-derived turbines are nothing new. They've been used in military and offshore drilling operations for decades, but this is the first time they've appeared in any meaningful way at data center sites. That speaks volumes about just how tight power supplies in the U.S. have become. In one of the more visible examples, OpenAI's parent group is deploying nearly 30 LM2500XPRESS units at a facility near Abilene, Texas, as part of its multi-billion-dollar Stargate project. Each unit spins up to 34 megawatts, fast enough to cold-start servers in under ten minutes. What they gain in fast deployment and ramp speed, they lose in thermal efficiency. Aeroderivative turbines run in simple-cycle mode, burning fuel without capturing waste heat, which puts them well below the efficiency of combined-cycle plants. Most run on diesel or gas delivered by truck, and require selective catalytic reduction to meet NOx limits. Still, it's not difficult to see the appeal. Even a small AI buildout can demand 100 megawatts or more, and with some utilities quoting lead times of five years or more, we should expect to see more stopgap power generation being implemented to meet burgeoning AI power demands.

[3]

Grounded jet engines take off again as datacenter generators

AI power demands drive operators to repurpose aircraft parts amid gas turbine shortages AI-driven datacenter energy needs are causing a shortage of gas turbines to power generators, with some operators reportedly turning to old aircraft engines instead. The rising demand for compute to feed the current AI development craze has seen datacenters adding capacity and new ones popping up, with a knock-on effect on the electricity supply. As The Register reported recently, US bit barns are set to consume 22 percent more grid power by the end of 2025 than the same time last year. But in many regions the energy grid can't keep pace with connection requests, leading operators to turn to on-site generation of their own power, as advised by Schneider Electric last year. But one thing leads to another, and now it seems that gas turbine manufacturers can't meet the sudden rise in demand, particularly in the US where there are more datacenters than anywhere else, leading to a shortage in some markets. The Financial Times says two-thirds of gas turbines for electricity generation come from three manufacturers: Japan's MHI, Germany's Siemens, and GE Vernova, the latter formed from a spin-out of General Electric's energy businesses. It quotes an MHI executive as saying: "There's so much demand right now that we can't meet it all," and that there is a lot of demand out of North America, meaning customers are now facing a three-year waiting list for delivery of turbine generators. A report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) notes the effect this is having in Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and the Philippines. Manufacturers are reporting wait times of up to five years for larger turbines, and are also starting to charge non-refundable reservation fees. One developer is said to have paid GE Vernova $25 million just to reserve a 2030 delivery slot. In response to the shortage, US company ProEnergy has now turned to offering repurposed jet engines, which is what gas turbines basically are. According to IEEE Spectrum, published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, some datacenters are already using PE6000 turbines supplied by ProEnergy to provide the power needed during construction of the facility and during its first few years of operation. When grid power becomes available, these turbines will be relegated to a backup role, supplement the grid supply, or sold on to another buyer. In this case, ProEnergy buys and overhauls used General Electric CF6 engines, a type used in commercial airliners, and adapts them to drive a generator rather than produce thrust. A shortage of gas turbines could cause problems for datacenter developers as the alternatives for on-site power generation are diesel generators, or more exotic solutions such as fuel cells or colocating facilities with wind farms. Some have suggested small modular reactors (SMRs) as another solution, but these are not likely to be ready before the end of the decade. ®

[4]

The fallout from the AI-fuelled dash for gas

Inside a building the size of an aircraft hangar, workers are rushing to make the finishing touches to a giant burgundy casing before its centrepiece is installed -- a 100-tonne turbine rotor. Composed of thousands of millimetre-precision parts manufactured and assembled over at least two years, the gas turbines weigh more than a Boeing 747. The factory in Takasago, in rural western Japan, is in the midst of a daunting battle to increase production to its highest level ever. At certain times in past years, visitors to the sprawling assembly plant owned by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries would have seen little to no activity at all inside this room. Until recently, gas was on the back foot as renewable power flourished and net zero emissions pledges rolled in. For the three manufacturers that control about two-thirds of the global supply of gas turbines -- Japan's MHI, Germany's Siemens and GE Vernova of the US -- the market looked to have irreversibly shrunk. Announcing 6,900 job cuts in 2017 due to "disruption of unprecedented scope and speed", Siemens predicted that demand would level out at 110 large units per year, versus the 400 the industry could produce. "Renewables are putting other forms of power generation under increasing pressure," said Lisa Davis, a board member, at the time. Siemens Energy's then North American president Rich Voorberg was later even more definitive: "Gas turbines were dead in 2022." Now, in 2025, they are very much alive. Orders are forecast to increase to 1,025 units this year, of which 183 will be large units, the most since 2011 and an almost 50 per cent increase on the average over the previous five years, according to Dora Partners, a specialist energy consultancy. The renaissance of gas is being driven by hunger for electricity from the data centres that are powering the boom in artificial intelligence. In 2024, the US Department of Energy forecast that data centres would consume 6.7 to 12 per cent of US electricity by 2028, up from 4.4 per cent in 2023. The computing capacity required to scale up AI requires reliable, round-the-clock power, causing the US to rapidly become the global epicentre of new gas-fired power plant construction. US energy company Entergy, for example, is building three new gas-fired power plants in Louisiana tied to Meta's colossal Hyperion data centre campus. "There's so much demand right now that we can't meet it all," says Yasuhiro Fujita, a 39-year veteran of MHI, stepping out of the assembly plant. "I feel this boom is a big one because it's worldwide. But right now, there's a lot of demand out of North America." The supply crunch means customers are now having to wait at least three years if they want to procure a turbine from the oligopoly. The trio are increasing production, but not fast enough to meet burgeoning demand. The turbine grab fuelled by US tech companies has both environmental and geopolitical consequences. Climate activists say the rush to gas is wildly out of sync with the legally binding Paris climate agreement signed in 2015 to limit global warming to well below 2C relative to pre-industrial averages. While turbines that can combust hydrogen to generate zero-emission power are under development, whether there will be a plentiful supply of clean fuel to burn for electricity is in doubt. The fallout from the US-led AI boom also has ramifications for Asia, touted as the big growth market for liquefied natural gas exports. The less carbon-intensive fossil fuel has long been touted as a "bridge" fuel between coal and renewables for emerging economies. The bottleneck in turbine supply could prevent developing Asian countries from completing gas-fired power plants in time to meet rising demand. "Nobody foresaw the US coming in like this for the turbines," says Raghav Mathur, a gas analyst at the consultancy Wood Mackenzie. "Even if Asian utilities want to place an order, they have to wait four or five years, which means they are stranded for the next four or five years." The limited availability also threatens to deny the US and Japan a powerful tool for regional influence -- supplying turbines that China is still far from mastering. With gas off the table and poor grid infrastructure limiting renewables, energy analysts say that Asia will be forced to turn to coal plants, often using Chinese technology, to keep the lights on. It's a far cry from just three years ago when the energy transition was like a mantra, says Takao Tsukui, president of Mitsubishi Power, the turbine arm of MHI. At the Asian power industry's annual conference in Bangkok in 2022, "it was almost like a sin to talk about coal," he says. "But today . . . the atmosphere of 'energy transition, energy transition and no more fossil fuels' has changed." Behind governments' shift to energy security and affordability over decarbonisation was the huge surge in gas prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Higher energy costs triggered global inflation and rising interest rates, creating obstacles for subsiding and financing clean energy projects. At that time, LNG prices surged by seven times to $70 per million British thermal units (mmbtu) as Europe rushed to replace Russian supplies. In Asia, the elevated costs made governments hesitant to build liquefied natural gas infrastructure that would lock them into an expensive fuel source. Prices have since come back down to $11 per mmbtu, but AI's surging power consumption is set to fuel a new wave of demand. The Paris-based International Energy Agency predicted in April that data centres' electricity use globally would double by 2030 to 945 terawatt hours, more than Japan's power consumption today. US utilities and AI developers have made a co-ordinated rush for gas turbines, spurred on by OpenAI and SoftBank's $500bn Stargate project to invest in AI infrastructure, including gas-fired power stations. The US is forecast to account for 46 per cent of global gas turbine orders this year, up from a recent historical average of 29 per cent, Dora Partners data shows. Data centre developers are even developing gas power plants independent of the grid. ExxonMobil is planning one such plant at a cost of about $15bn, according to a person familiar with the project. Christian Buch, chief executive of Siemens Energy, says that two years ago, it only sold one gas turbine in the US. "One, in the whole year. Now, we are at what, 150 or so?" he adds, before his assistant chimes in to clarify that it is closer to 200 units. But in the long term, he adds, he doesn't believe turbine supply snags driven by the US demand surge will change the LNG market. Tsukui of Mitsubishi Power says the industry received orders for turbines representing 40 gigawatts per year between 2021 and 2023 but that has leapt to 60-70 GW between 2024 and 2026. Manufacturers are now demanding deposits to reserve places in waiting lines -- last used during another boom in the early 2000s -- as well as charging premiums for earlier deliveries, according to industry experts. As of April, GE Vernova said that it was largely sold out for 2026 and 2027. It is now in talks with customers to deliver in 2030. Tsukui predicts high demand for five to 10 years "at least" because of the strength of demand from AI. He believes that this time is fundamentally different from the melt-up in the gas turbine market around 2000 caused by US power sector deregulation. "There's real demand from data centres and AI. That's decisively different from back then," he says. "If somebody is going to tell me AI is going to stop and nobody is going to use it, then I'd think this would be a risk but I don't think that's going to happen." The market is also seeing strong demand for turbines out of the Middle East, as the region seeks to use domestic resources to meet rising electricity demand, as well as units used to compress gas for export. Collective confidence in the boom's veracity and longevity means the big three are lifting production. MHI is pursuing a doubling of production within two years. Scaling up the supply chain will be challenging as suppliers are stretched trying to cater to booming aerospace and defence demand. All turbine makers aim to modernise and automate, instead of building new facilities, to minimise the risk of stranded assets. However, optimism is not universal at a time when markets are increasingly jittery about overspending on AI infrastructure. Back in the factory, Fujita says every time the industry booms, the bust soon follows. "The big question for me is whether this is something which is going to be sustained or like a souffle," says Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a gas specialist at Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy. "People are starting to wonder if there's an AI bubble. Who's going to pay for these [AI] services and are we going to make advances in energy efficiency?" As manufacturers increasingly cater to AI demand in the US, they are at risk of passing over the next growth engine of LNG consumption: emerging markets. South-east Asia is a prime example of a market facing unintended consequences of the AI boom. Industry officials say that several LNG projects would have to be scrapped or delayed due to the difficulty in securing gas turbines. Many put off decisions to pursue LNG when prices spiked in 2022. Today, infrastructure availability and cost has surfaced as a pain point. "The LNG-to-power industry in south-east Asia has faced many, many years of hurdles related to financing. And I would put this gas turbine shortage as the cherry on top," says Sam Reynolds, a researcher at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Vietnam and the Philippines, which have bet big on LNG, will be among the hardest hit and miss their targets for LNG development. IEEFA predicts that Vietnam will miss its 2030 targets to produce LNG-fired power capacity of 22.5GW by 2030 from the current 1.6GW. "The expansion of LNG-related infrastructure in the region will be much, much slower than the industry is hoping for," says Reynolds. One Vietnamese energy project developer says that gas power stations aiming to start within three years would fail to meet their timelines. "I do not think it is possible because of the time to order the turbines. Without more investment in renewables, Vietnam will have a power shortage if they cannot get the big power infrastructure built," they add. That could affect factory operations and have wider implications for export-dependent Vietnam, which has become a critical link to global supply chains as manufacturers shift production away from China. Cuong Tran Duc, managing director of CMIT Group, which advises power project developers in Vietnam, says that only one gas-fired power plant under development has secured a contract for its turbine. "The turbine shortage poses a severe threat to Vietnam's power development goals," he says. A silver lining of the crunch may be that it avoids locking Asian economies into a fossil fuel for decades. It may even accelerate energy transition efforts for some of the world's largest carbon emitters. Recent infrastructure challenges and the volatility of gas prices are "creating more opportunities for solar and battery and wind," says Dinita Setyawati, a senior energy analyst, Asia, at Ember. Indonesia's deputy coordinating minister for basic infrastructure, Rachmat Kaimuddin, says geothermal and hydropower offer a way forward. "The path of transition doesn't have to go through transition fuel," he says. But weak power grids, which are not connected between countries, will put a limit on how much renewables can make up for gas. Siemens Energy's Buch says that "some countries are able to leapfrog to renewables, but the one big challenge I see in south-east Asia is the weaker grid", which combined with high LNG prices means that "unfortunately we will see a slower conversion from coal to gas". The resulting uncertainty for LNG's role in the energy mix opens another door for China in south-east Asia. Unlike with many other sources of power, China does not dominate the supply of key equipment and infrastructure for gas plants. Its domestic electricity generation is primarily a mix of coal and renewables, with gas accounting for 3 per cent. Industry executives and analysts say that Chinese rivals are too far behind to break into the oligopoly any time soon. Incremental gains by the turbine manufacturing industry's big three to reach about 64 per cent efficiency, saving operators millions of dollars in fuel over years, were hard earned and not easily replicated. "There's no significant challenge to the gas turbine industry from China," says Anthony Brough, president of Dora Partners. Instead, many fear that the developing countries will have no choice but to rely on coal power technology provided by the region's hegemon. "The reality is that over the next five years, gas turbines cannot be supplied to this region. People are worried that Chinese coal-fired power plants will fill the vacuum," says Tetsuya Watanabe, president of the Economic Research Institute for Asean and East Asia, a Jakarta-based think-tank backed by the Japanese government. Even though Beijing pledged to stop financing new overseas coal plants in 2021 and the number of developments has dropped, many projects are still moving ahead. Japan, a global giant in gas infrastructure, has ambitions to place itself at the centre of the region's energy developments. In 2023, it launched the Asian Zero Emission Community, akin to China's Belt and Road Initiative, in financing energy infrastructure. Of 158 memorandums of understanding analysed under the scheme, 56 support fossil fuel technologies, according to Zero Carbon Analytics, showing the major role for gas. But if developing countries are priced out of the LNG market by the requirements of Big Tech, the huge growth in supply will struggle to find a home and new projects will be harder to justify. Alaska LNG, for example, the mega-gas project that the Trump administration is trying to strong-arm Japan and South Korea to support, is dependent on demand for gas in Asia's developing economies. One senior Japanese gas trader provides a frank assessment on the outlook in Asia for gas based on how expensive turbines have become and LNG remains. "All gas turbines are taken by the Americans, Europeans and Middle Eastern countries," the trader says. "It's going to be very difficult for Asian emerging economies to increase their LNG exposure."

[5]

Massive AI data center buildouts are squeezing energy supplies -- New energy methods are being explored as power demands are set to skyrocket

A perfect storm of massive data centre buildout and new innovations in energy could materially change what our supplies look like in the future. The world is building the electricity system for artificial intelligence on the fly. Over the next five years, the power appetite of data-center campuses built for training and serving large AI models will collide with the reality of permitting, transmission backlogs, and siting constraints. All that could materially change how much, from where, and what type of energy supplies we obtain. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects global data centre electricity demand will more than double to 945 terawatt-hours by 2030, with AI being the largest single driver of the rise. European energy demand alone could jump from about 96 TWh in 2024 to 168 TWh by 2030. The enormous rise in energy demand didn't just start with the November 2022 release of ChatGPT. The electricity use of hyperscalers has been rising more than 25% for seven years running, according to analysis by Barclays. But the amount of energy needed for AI inference and training has seen those already prodigious rises increase even further. "AI has been rolled out everywhere," Chris Preist, professor of sustainability and computer systems at the University of Bristol, said in an interview with Tom's Hardware Premium. "'Everything everywhere all at once' is the phrase I like to use for AI," Preist said. "It's doing what technologies have always done, but it's doing it at a far, far higher speed." People like Sam Altman are enormously bullish on the future of AI, but are hyperconscious of the energy crunch that it creates. In an essay published in late September, Altman wrote of his vision "to create a factory that can produce a gigawatt of new AI infrastructure every week." He added: "The execution of this will be extremely difficult; it will take us years to get to this milestone and it will require innovation at every level of the stack, from chips to power to building to robotics." As Altman says, everything affects our energy systems. The IEA's forecasts have proven to be a wake-up call for the energy sector and the AI industry. Anthropic has stated that it believes it'll need 2GW and 5GW data centres as standard to develop its advanced AI models in 2027 and 2028. It also forecasts that the total frontier AI training demand in the United States will reach up to 25GW by 2028. That's just for training: inference will add the same amount to that, Anthropic forecasts, meaning the US alone will need 50GW of AI capacity by 2028 to retain its world-leading position. Already, the data centre sector is responding by building out huge numbers of new projects: spending on U.S. data centre construction grew 59% in 2023 to $20 billion, and to $31 billion - another 56% leap - in 2024. In 2021, pre-ChatGPT, annual private data construction was only around $10 billion. All those data centres need a reliable supply to power them, so companies are starting to consider how to mitigate an energy crunch that strains grids to their breaking point by building lots of new generation capacity. But questions remain about whether it's needed. Preist is at pains to point out that globally, we have a surfeit of energy supply. "In the case of digital tech, it's actually a local shortfall, not a global shortfall," he said. But in areas where AI demand is high, there's often a gap between the demand to power the AI systems being used and the supply for them. Having access to reliable power sources is a key consideration for those building data centres, with 84% of data centre leaders telling Bloom Energy in an April 2025 survey that it was their top consideration in where they choose to build - more than twice as important as proximity to end users, or the level and type of local regulations they would face. What type of energy supplies are being built is also changing. A radical shift is taking place with AI companies moving towards firm clean power underpinned by nuclear and geothermal. Constellation is fast-tracking a restart of the shuttered Three Mile Island Unit 1 (renamed the Crane Clean Energy Centre) after striking a 20-year power purchase agreement (PPA) with Microsoft, which, if it meets its ambitious target of a 2027 restart date, could be the first full restart of a U.S. nuclear plant. Analysts estimate Microsoft is paying a premium for certainty of supply. Amazon has also funded a $500 million raise for X-energy and set a target to deploy more than 5GW of small modular reactors across the US by 2039, pairing equity stakes with future PPAs. Both deals are designed to bankroll reliable low-carbon supplies for their AI campuses. The shift isn't just in what's built, but how it's supplied. Rather than annual renewable matching, buyers are signing hour-by-hour, location-specific carbon-free supply and paying for storage to firm it. Data centers are being placed in areas with low-carbon energy supplies and faster planning processes. But the hard limit remains the wires. Even where generation exists, securing a new high-voltage tie-in can take years, so AI data campuses are planning for staged rollout, and until they are fully complete, temporary solutions to build out capacity. AI firms, such as xAI, are spending big to try to install energy supplies as quickly as they can. However, Izzy Woolgar, director of external affairs at the Centre for Net Zero, said in an interview with Tom's Hardware Premium that the purported surfeit in supply might not be as great as initially thought. "We know data centres and electricity are driving up demand today," she said. 'This creates two challenges: first to accurately forecast the energy required to power those centres, and secondly, to meet that demand as quickly and cleanly as possible in the context of an already strained grid." Choosing clean energy options is tricky, partly because alternative power sources aren't always available, and energy demand must be met immediately to support the massive needs of AI. Developers can sign record renewable deals, but connecting new supply remains the hard limit. In the United States, the median time from requesting a grid interconnection to switching on stretched to nearly five years for projects completed in 2022-23 - up from three years in 2015 and less than two years in 2008. That delay is system-wide and rising across regions. "The quickest way of getting around that is to install energy sources at the data centre itself," said Preist. "Ideally, those would be renewable, but often the quickest way of getting it in places is mobile gas generation." It means that we're seeing increased demand for all types of energy, including fossil fuels. Those constraints on the grid and supplies more generally are why tech companies are spending billions to invest in small modular reactors and other supply sources. "We are rapidly building out our infrastructure as part of the energy transition, but confronted by a congested grid, data centre operators are exploring bypassing delays and seeking out direct connections to generators," Woolgar said. She pointed out that companies have explored hook-ups to gas-fired power plants, and many are investing heavily in unproven technologies such as nuclear small modular reactors (SMRs), which are already being invested in and showcased by the likes of Amazon. But many SMRs need to clear hurdles of red tape, which won't make it feasible for all until the end of the decade. And that's the issue, said Woolgar. "The long development times of these major projects will not meet the immediate demands of AI, and we are overlooking the ability of proven and reliable clean technology like solar, wind, and battery storage that can be deployed in as little as two to three years," she said. As well as things like small modular reactors, other alternatives could be pursued. One of those areas is renewable microgrids, which the Centre for Net Zero's modelling indicates could cost 43% less to run than nuclear alternatives. That can help the world get power where it is needed in the short term, Woolgar explained. There are also environmental considerations that are resulting in an energy crunch. Water for cooling is becoming a terminal issue in many regions. In areas of high power density, there's a consideration towards direct liquid and immersion cooling to try and slash water demand and reduce fan-based cooling. Given all the debate around whether we're currently in an AI bubble, the level of energy supply expansion has some worried. "Predicted future surges in demand from AI could well be overplayed, as current projections often fail to account for emerging or future breakthroughs," said Woolgar. Preist is also worried about whether we're about to spend vast sums to build energy supplies that won't be needed if the visions of the future powered by AI turn out to be more science fiction than fact. "There is a risk that energy companies overprovision for a bubble which then bursts, and then you're stuck," he said. "You're stuck with a load of infrastructure, gas power stations, et cetera, which the residential people need to effectively pay for through overpriced energy." Woolgar explained that she believed the current plans for building out energy infrastructure to account for future AI demand didn't account for improvements in technology efficiency. "The upfront energy costs of training models tend to appear quickly, while the downstream benefits and advancements are less immediate and certain," she said. For that reason, it was likely that the huge buildout won't need to be quite as large as expected. "The requirements to train models today won't remain constant," said Woolgar. She points out that DeepSeek's R1 model, launched earlier this year, was trained using just 10% of Meta's Llama computational resources, "and chips will inevitably get more efficient when it comes to energy consumption." There's also the idea that, as well as becoming more efficient, infrastructure providers can become more intelligent about recycling waste outputs, such as heat, from the massive data centres that will have to be built to meet society's insatiable AI demand. "There is significant heat, and ideally it would be put into district heating systems," said Preist, pointing to the design of Isambard AI - a small data centre when looked at from future scaling standards, but quite large by traditional standards. That has been "designed to allow the heat to be reused in a district heating system", even though the infrastructure to connect it up to a district heating system hasn't yet been built. Some work is going on in this area already, in large part thanks to the collateral benefits of the adoption of advanced cooling techniques such as immersion cooling to try and reduce the need for energy-intensive traditional cooling in data centres. The power density of next-generation GPUs like Rubin and Rubin Ultra, which is projected to require between 1.8kW and 3.6kW per module, with entire racks approaching 600 kW, means that air cooling isn't a practical solution for these deployments. In their place, immersion cooling, where servers are submerged in dielectric fluids, has been proposed as an alternative. That recovered heat from immersion cooling could be redirected to use in nearby residential energy grids or industrial facilities, experts reckon. It all shows how quickly the face of energy is changing as AI stretches, then changes, supplies. And with multiple companies racing to try and compete with one another to gain an edge, build up their customer base and keep a foothold in the market, the demand for more varied sources of supply seems like it's going to continue to rise in the years to come.

[6]

Britains's AI gold rush hits a wall: not enough electricity

Energy Secretary Miliband promises renewable utopia for green and pleasant land... filled with datacenters Energy is essential for delivering the UK governments' AI ambitions, but Britain faces a critical question: how can it supply enough power for rapidly expanding datacenters without causing blackouts or inflating consumer bills? At Energy UK's annual London conference this week, Energy Secretary Ed Miliband made his position clear: renewables are the future, and fossil fuels drive both climate damage and the nation's inflated energy costs. What's less clear is how to reach this renewable utopia given decades of infrastructure underinvestment. "Building clean energy is the right choice for the country because, despite the challenges, it is the only route to a system that can reliably bring down bills for good, and give us clean energy abundance," Miliband claims. The UK reportedly has the world's most expensive electricity, largely because wholesale electricity prices track gas prices, which surged after Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Gas-fired generators serve as the backup when solar and wind fall short -- a frequent occurrence on Britain's gray, windless days. The obvious solution -- more solar farms and wind turbines -- faces significant obstacles. Offshore wind farms can take years to construct, while onshore projects, though faster to build, face lengthy land acquisition and planning permission processes. Local opposition to solar farms is fierce, with many viewing them as blights on the landscape, particularly when built on farmland. The government's answer is to streamline the planning process by amending the National Planning Policy Framework or designating projects as critical national infrastructure, as it did with datacenters. But even with expedited approvals, new power projects must keep pace with datacenter construction. Several major datacenters have broken ground near London's M25 in the past year alone, including Europe's largest planned cloud and AI datacenter near South Mimms, a Google facility at Waltham Cross, and projects at Abbots Langley, East Havering, and one at Woodlands Park, near Iver in Buckinghamshire - previously been rejected but now listed as approved on the developers' website.. The government's "AI Growth Zones," targeted at sites with existing grid connections like decommissioned power stations, hint at recognition of the scale challenge. And the energy regulator, Ofgem, gave the go-ahead in July to an investment program that will deliver £15 billion ($20 billion) for gas transmission and distribution networks and £8.9 billion ($12 billion) for what is being touted as "the biggest expansion of the electricity grid since the 1960s." In July, energy regulator Ofgem approved a £23.9 billion ($32 billion) investment program -- £15 billion for gas networks and £8.9 billion for what's being called the biggest electricity grid expansion since the 1960s. However, The Guardian noted that householders will fund this through higher charges, with bills rising by £104 ($140) by 2031 -- on top of already inflated costs. Replacing gas-fired generators as the reliable baseload source remains problematic. Unlike the US, Britain can't return to coal -- its last coal-fired power station closed last year. Battery energy storage systems (BESSs) offer one solution for storing excess renewable energy. But the gap is enormous: according to RenewableUK, Britain had 5,013 MW of operational battery storage at year-end, while peak demand on a cold day reaches 61.1 GW. Nuclear power is the elephant in the room. And as Miliband states, much of the UK's nuclear fleet dates to the 1980s, and no new station has come online since Sizewell B 30 years ago. Construction of a new reactor, Hinkley Point C, began in December 2018, with expected completion by 2027, but EDF, the company building it, now says it is unlikely to be operational before 2030. The overall cost has ballooned from £26 billion ($35 billion) to between £31 and £34 billion ($42 to $47 billion). Small modular reactors (SMRs) are gaining attention from government and datacenter operators, but the technology remains largely untested, and unlikely to be ready for another decade. "Omdia has talked with many power generation project developers and the consensus is that broad market acceptance and availability is likely around 2035, so about 10 years out," Omdia principal analyst Alan Howard, told us earlier this year. A recent study also found that renewable energy sources can provide power for datacenters more cheaply than SMRs, when paired with battery storage. However, the datacenters are being built now, and the government also expects Brits to switch to electric vehicles and give up gas-fired central heating for alternatives such as electric-powered heat pumps. "In the years ahead, we expect a massive increase in electricity demand - around 50 percent by 2035 and a more than doubling by 2050," Miliband said in his speech, calling it "a massive opportunity for us." "We want as a country to seize the opportunities of electric vehicles that are cheaper to run, new industries such as AI, and the benefits of electrification across the economy," he added. Whatever Miliband plans to ensure there is sufficient energy for all this, he needs to act fast, or his government's ambitions to pepper the country with AI datacenters are going to be thwarted by lack of power, soaringe energy costs - or both. ®

[7]

What's Powering All These Futuristic Data Centers? In Many Cases Repurposed Jet Engines

AI needs a lot of energy, and from Sam Altman, to Bill Gates, to Peter Thiel, tech billionaires with heavy involvement in AI tend to also invest in the futuristic energy moonshot that is nuclear fusion. But the giant, energy-sucking data centers of today are powered by the energy sources of today, includingâ€"it turns outâ€"sputtering old repurposed airplane engine cores. As noticed by IEEE Spectrum’s Drew Robb earlier this week, Missouri-based company ProEnergy is doing healthy business by supplying used General Electric CF6-80C2 jet cores, which are “high-bypass turbofan engines†according to a PDF on the GE aerospace website, to data centers that are so desperate for energy they can’t wait for power utilities to supply it. These babies were designed to propel 767s through the sky, but with the right modifications, they can be locked down on concrete slabs or packaged into trailers, wired up to data centers, and dialed up to 48 megawatts of power generation. If my numbers are right (and here’s where I’m getting them) that’s enough to power about 32,160 American homes. Or, perhaps, an AI cluster. ProEnergy’s commercial operations VP Landon Tessmer spoke to IEEE Spectrum’s Robb at the World Power show in San Antonio earlier this month, telling him that 21 such aviation engine generators have been sold to data centers for use during construction. They’ll be the intended power source for years after these centers are up and running, Tessmer explained, and have the potential to become backup generators once grid power is in place.

[8]

'AI' data centers are so power-hungry, they're now using old jet engines

Data centers that can't be supplied by local energy grids are being augmented with refurbished engines from planes. "AI" needs a lot of computing resources, which is why new data centers are cropping up anywhere there's cheap land. But powering all those hungry servers takes a lot of energy, and overburdened power grids aren't always up to the challenge. In addition to diesel generators and resurrected nuclear plants, data center operators are now repurposing airplane engines. Yes, really. At the Data Center World Power Show in Texas, natural gas provider ProEnergy is showing off the PE6000, a power generator built by repurposing old jet engines from planes like the Boeing 747. Promotional pages claim this design can output 48 megawatts at a time, four to five times as much energy as a single-family home uses in a year. IEEE Spectrum (via Tom's Hardware) reports that 21 of these gas-powered turbines have already been sold, specifically to data center operators in locations that don't have the necessary electrical grid capacity. On ProEnergy's promotional page, you can see a photo of the engine installed next to some kind of industrial building. And yeah, it looks just like a jet engine clamped in place on the ground, locked into a steel frame and set on gravel. I can only imagine what it sounds like because there's no mention of noise or a video of the turbine in operation. But the presumably similar LM6000 was featured in the YouTube video below: The staggering energy requirements of data centers -- many of which are being built exclusively for the generative "AI" industry -- are causing no small amount of problems. In addition to straining conventional power grids and causing energy prices to skyrocket for both regular home customers and businesses, noise and pollution from stopgap, on-site energy generation is affecting people living nearby. In Tennessee, the data center running Elon Musk's xAI systems is using gas turbines and pumping out harmful emissions, including nitrogen oxides known to contribute to respiratory diseases. Locals have been fighting to get the data center restricted or shut down, a fight between industry and citizens that's being mirrored around the US and the world.

[9]

Inside 'data centre alley' - the biggest story in economics right now

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player If you ever fly to Washington DC, look out of the window as you land at Dulles Airport - and you might snatch a glimpse of the single biggest story in economics right now. There below you, you will see scattered around the fields and woods of the local area a set of vast warehouses that might to the untrained eye look like supermarkets or distribution centres. But no: these are in fact data centres - the biggest concentration of data centres anywhere in the world. For this area surrounding Dulles Airport has more of these buildings, housing computer servers that do the calculations to train and run artificial intelligence (AI), than anywhere else. And since AI accounts for the vast majority of economic growth in the US so far this year, that makes this place an enormous deal. Down at ground level you can see the hallmarks as you drive around what is known as "data centre alley". There are enormous power lines everywhere - a reminder that running these plants is an incredibly energy-intensive task. This tiny area alone, Loudoun County, consumes roughly 4.9 gigawatts of power - more than the entire consumption of Denmark. That number has already tripled in the past six years, and is due to be catapulted ever higher in the coming years. Inside 'data centre alley' We know as much because we have gained rare access into the heart of "data centre alley", into two sites run by Digital Realty, one of the biggest datacentre companies in the world. It runs servers that power nearly all the major AI and cloud services in the world. If you send a request to one of those models or search engines there's a good chance you've unknowingly used their machines yourself. Their Digital Dulles site, under construction right now, is due to consume up to a gigawatt in power all told, with six substations to help provide that power. Indeed, it consumes about the same amount of power as a large nuclear power plant. Walking through the site, a series of large warehouses, some already equipped with rows and rows of backup generators, there to ensure the silicon chips whirring away inside never lose power, is a striking experience - a reminder of the physical underpinnings of the AI age. For all that this technology feels weightless, it has enormous physical demands. It entails the construction of these massive concrete buildings, each of which needs enormous amounts of power and water to keep the servers cool. Read more from Ed Conway: Blow to UK's bid to become minerals superpower There's more to your AirPods than meets the eye We were given access inside one of the company's existing server centres - behind multiple security cordons into rooms only accessible with fingerprint identification. And there we saw the infrastructure necessary to keep those AI chips running. We saw an Nvidia DGX H100 running away, in a server rack capable of sucking in more power than a small village. We saw the cooling pipes running in and out of the building, as well as the ones which feed coolant into the GPUs (graphic processing units) themselves. Such things underline that to the extent that AI has brainpower, it is provided not out of thin air, but via very physical amenities and infrastructure. And the availability of that infrastructure is one of the main limiting factors for this economic boom in the coming years. According to economist Jason Furman, once you subtract AI and related technologies, the US economy barely grew at all in the first half of this year. So much is riding on this. But there are some who question whether the US is going to be able to construct power plants quickly enough to fuel this boom. For years, American power consumption remained more or less flat. That has changed rapidly in the past couple of years. Now, AI companies have made grand promises about future computing power, but that depends on being able to plug those chips into the grid. Last week the International Monetary Fund's chief economist, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, warned AI could indeed be a financial bubble. He said: "There are echoes in the current tech investment surge of the dot-com boom of the late 1990s. It was the internet then... it is AI now. We're seeing surging valuations, booming investment and strong consumption on the back of solid capital gains. The risk is that with stronger investment and consumption, a tighter monetary policy will be needed to contain price pressures. This is what happened in the late 1990s." 'The terrifying thing is...' For those inside the AI world, this also feels like uncharted territory. Helen Toner, executive director of Georgetown's Center for Security and Emerging Technology, and formerly on the OpenAI board, said: "The terrifying thing is: no one knows how much further AI is going to go, and no one really knows how much economic growth is going to come out of it. "The trends have certainly been that the AI systems we are developing get more and more sophisticated over time, and I don't see signs of that stopping. I think they'll keep getting more advanced. But the question of how much productivity growth will that create? How will that compare to the absolutely gobsmacking investments that are being made today?" Whether it's a new industrial revolution or a bubble - or both - there's no denying AI is a massive economic story with massive implications. For energy. For materials. For jobs. We just don't know how massive yet.

Share

Share

Copy Link

As AI development skyrockets, data centers are facing an unprecedented energy crunch, leading to innovative and controversial solutions including repurposed jet engines and renewed interest in gas turbines.

AI's Growing Power Problem

AI's rapid expansion creates unprecedented energy demand, pushing data centers to find new power solutions. This growth challenges them to balance energy needs with environmental concerns and grid limitations

1

2

.

Source: Tom's Hardware

Innovative Temporary Power

Data centers utilize unconventional power. Repurposing commercial jet engines into gas turbines for on-site electricity is a prime example

2

3

. ProEnergy adapts retired GE CF6 engines. These aeroderivative turbines, generating up to 48 MW, are immediate solutions. OpenAI, for instance, installs nearly 30 LM2500XPRESS units (34 MW each) for its Texas Stargate project2

.

Source: Tom's Hardware

Gas Turbines' Revival

The AI boom surprisingly revitalized the gas turbine industry. Manufacturers like MHI, Siemens, and GE Vernova now face high demand after years of decline

4

. Gas turbine orders are projected to reach 1,025 units in 2025, with large units highest since 2011—a nearly 50% increase over five years4

. This highlights urgent needs.Related Stories

Environmental & Global Impact

The AI power race alarms environmentalists; increased reliance on gas conflicts with carbon targets

1

4

. US tech demand for turbines causes delays (up to five years) for Asian nations. This might force developing countries to use coal-fired plants, potentially with Chinese tech4

.

Source: The Register

Pursuing Sustainable Futures

Long-term, AI explores sustainable energy. Investments flow into nuclear and geothermal power. Microsoft secured a 20-year agreement to restart Three Mile Island Unit 1; Amazon backs small modular reactors

5

. IEA projects global data center electricity demand will more than double to 945 TWh by 2030, driven mainly by AI5

. This stresses critical sustainable innovation.References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

[3]

Related Stories

AI's Energy Dilemma: Data Centers Push Power Grids to the Limit

15 Oct 2024•Technology

Boom Supersonic pivots jet engine tech to power AI data centers with 42 MW turbine

10 Dec 2025•Business and Economy

US Power Grid Struggles to Keep Pace with AI Data Center Boom, While China Surges Ahead

15 Aug 2025•Business and Economy

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with Defense Production Act over AI military use restrictions

Policy and Regulation

2

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

3

Anthropic accuses Chinese AI labs of stealing Claude through 24,000 fake accounts

Policy and Regulation