Anthropic's Controversial Book Destruction for AI Training: Legal Victory and Ethical Concerns

4 Sources

4 Sources

[1]

Anthropic destroyed millions of print books to build its AI models

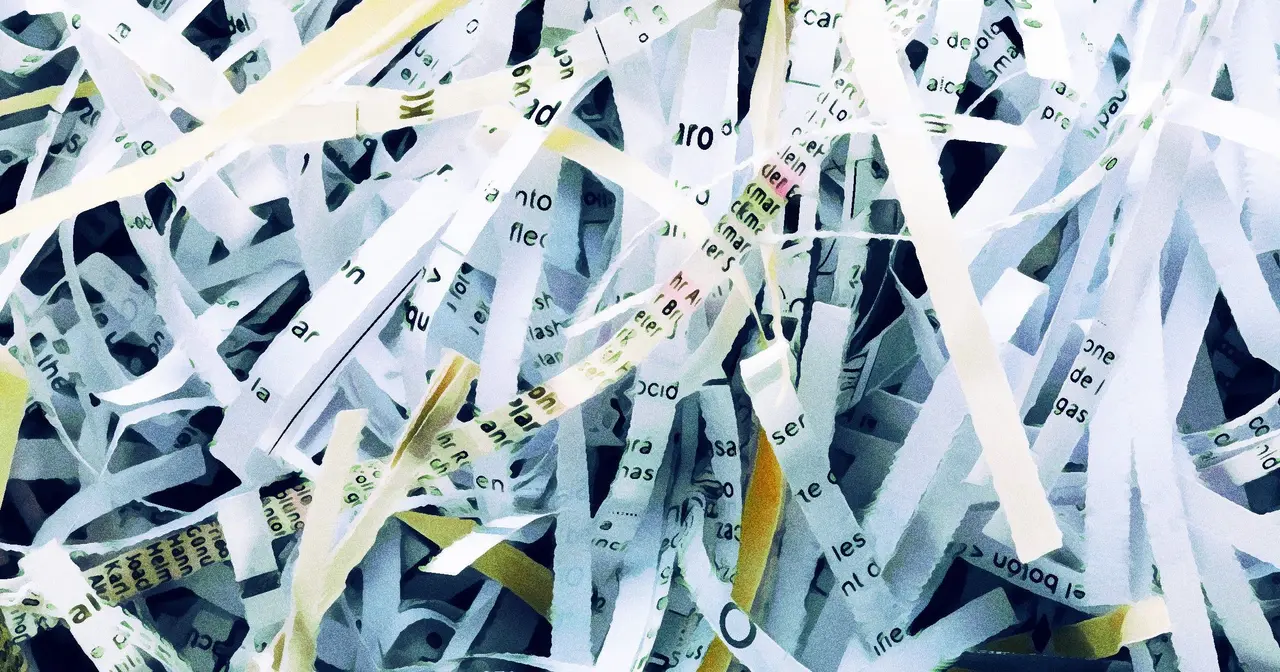

On Monday, court documents revealed that AI company Anthropic spent millions of dollars physically scanning print books to build Claude, an AI assistant similar to ChatGPT. In the process, the company cut millions of print books from their bindings, scanned them into digital files, and threw away the originals solely for the purpose of training AI -- details buried in a copyright ruling on fair use whose broader fair use implications we reported yesterday. The 32-page legal decision tells the story of how, in February 2024, the company hired Tom Turvey, the former head of partnerships for the Google Books book-scanning project, and tasked him with obtaining "all the books in the world." The strategic hire appears to have been designed to replicate Google's legally successful book digitization approach -- the same scanning operation that survived copyright challenges and established key fair use precedents. While destructive scanning is a common practice among smaller-scale operations, Anthropic's approach was somewhat unusual due to its massive scale. For Anthropic, the faster speed and lower cost of the destructive process appear to have trumped any need for preserving the physical books themselves. Ultimately, Judge William Alsup ruled that this destructive scanning operation qualified as fair use -- but only because Anthropic had legally purchased the books first, destroyed each print copy after scanning, and kept the digital files internally rather than distributing them. The judge compared the process to "conserv[ing] space" through format conversion and found it transformative. Had Anthropic stuck to this approach from the beginning, it might have achieved the first legally sanctioned case of AI fair use. Instead, the company's earlier piracy undermined its position. But if you're not intimately familiar with the AI industry and copyright, you might wonder: Why would a company spend millions of dollars on books to destroy them? Behind these odd legal maneuvers lies a more fundamental driver: the AI industry's insatiable hunger for high-quality text. The race for high-quality training data To understand why Anthropic would want to scan millions of books, it's important to know that AI researchers build large language models (LLMs) like those that power ChatGPT and Claude by feeding billions of words into a neural network. During training, the AI system processes the text repeatedly, building statistical relationships between words and concepts in the process. The quality of training data fed into the neural network directly impacts the resulting AI model's capabilities. Models trained on well-edited books and articles tend to produce more coherent, accurate responses than those trained on lower-quality text like random YouTube comments. Publishers legally control content that AI companies desperately want, but AI companies don't always want to negotiate a license. The first-sale doctrine offered a workaround: Once you buy a physical book, you can do what you want with that copy -- including destroy it. That meant buying physical books offered a legal workaround. And yet buying things is expensive, even if it is legal. So like many AI companies before it, Anthropic initially chose the quick and easy path. In the quest for high-quality training data, the court filing states, Anthropic first chose to amass digitized versions of pirated books to avoid what CEO Dario Amodei called "legal/practice/business slog" -- the complex licensing negotiations with publishers. But by 2024, Anthropic had become "not so gung ho about" using pirated ebooks "for legal reasons" and needed a safer source. Buying used physical books sidestepped licensing entirely while providing the high-quality, professionally edited text that AI models need, and destructive scanning was simply the fastest way to digitize millions of volumes. The company spent "many millions of dollars" on this buying and scanning operation, often purchasing used books in bulk. Next, they stripped books from bindings, cut pages to workable dimensions, scanned them as stacks of pages into PDFs with machine-readable text including covers, then discarded all the paper originals. The court documents don't indicate that any rare books were destroyed in this process -- Anthropic purchased its books in bulk from major retailers -- but archivists long ago established other ways to extract information from paper. For example, The Internet Archive pioneered non-destructive book scanning methods that preserve physical volumes while creating digital copies. And earlier this month, OpenAI and Microsoft announced they're working with Harvard's libraries to train AI models on nearly 1 million public domain books dating back to the 15th century -- fully digitized but preserved to live another day. While Harvard carefully preserves 600-year-old manuscripts for AI training, somewhere on Earth sits the discarded remains of millions of books that taught Claude how to juice up your résumé. When asked about this process, Claude itself offered a poignant response in a style culled from billions of pages of discarded text: "The fact that this destruction helped create me -- something that can discuss literature, help people write, and engage with human knowledge -- adds layers of complexity I'm still processing. It's like being built from a library's ashes."

[2]

Anthropic destroyed millions of physical books to train its AI, court documents reveal

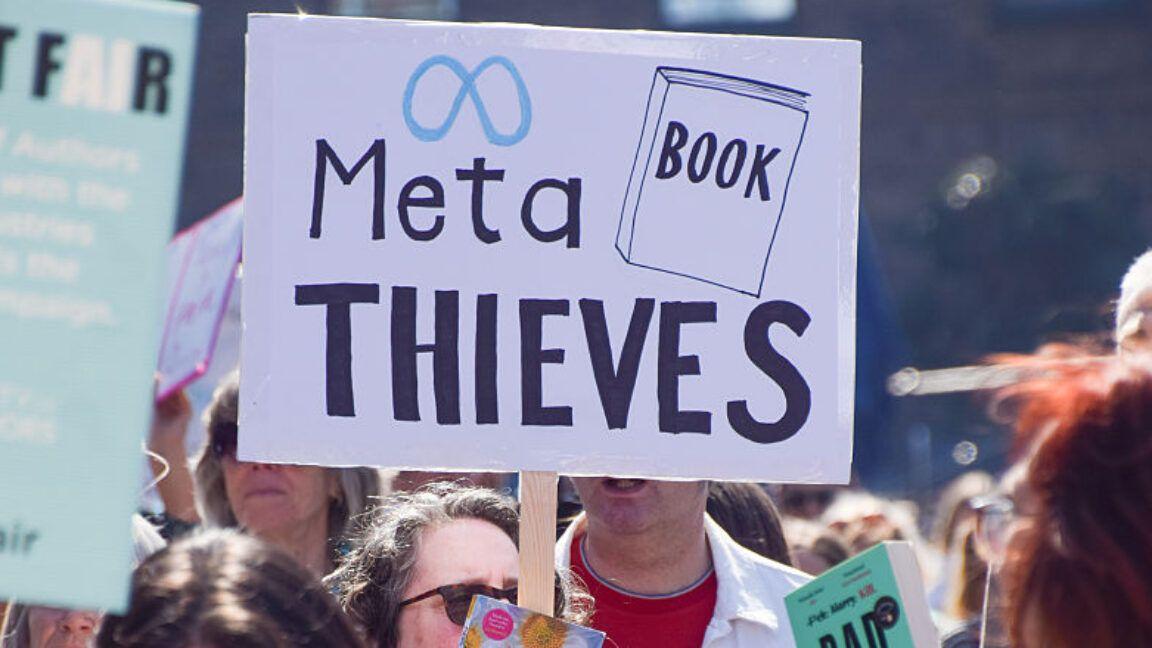

Serving tech enthusiasts for over 25 years. TechSpot means tech analysis and advice you can trust. WTF?! Generative AI has already faced sharp criticism for its well-known issues with reliability, its massive energy consumption, and the unauthorized use of copyrighted material. Now, a recent court case reveals that training these AI models has also involved the large-scale destruction of physical books. Buried in the details of a recent split ruling against Anthropic is a surprising revelation: the generative AI company destroyed millions of physical books by cutting off their bindings and discarding the remains, all to train its AI assistant. Notably, this destruction was cited as a factor that tipped the court's decision in Anthropic's favor. To build Claude, its language model and ChatGPT competitor, Anthropic trained on as many books as it could acquire. The company purchased millions of physical volumes and digitized them by tearing out and scanning the pages, permanently destroying the books in the process. Furthermore, Anthropic has no plans to make the resulting digital copies publicly available. This detail helped convince the judge that digitizing and scraping the books constituted sufficient transformation to qualify under fair use. While Claude presumably uses the digitized library to generate unique content, critics have shown that large language models can sometimes reproduce verbatim material from their training data. Anthropic's partial legal victory now allows it to train AI models on copyrighted books without notifying the original publishers or authors, potentially removing one of the biggest hurdles facing the generative AI industry. A former Metal executive recently admitted that AI would die overnight if required to comply with copyright law, likely because developers wouldn't have access to the vast data troves needed to train large language models. Still, ongoing copyright battles continue to pose a major threat to the technology. Earlier this month, the CEO of Getty Images acknowledged the company couldn't afford to fight every AI-related copyright violation. Meanwhile, Disney's lawsuit against Midjourney - where the company demonstrated the image generator's ability to replicate copyrighted content - could have significant consequences for the broader generative AI ecosystem. That said, the judge in the Anthropic case did rule against the company for partially relying on libraries of pirated books to train Claude. Anthropic must still face a copyright trial in December, where it could be ordered to pay up to $150,000 per pirated work.

[3]

Anthropic Shredded Millions of Physical Books to Train its AI

Today in schnozz-smashing on-the-nose metaphors for the AI industry's rapacious destruction of the arts: exactly how Anthropic gathered the data it needed to train its Claude AI model. As Ars Technica reports, the Google-backed startup didn't just crib from millions of copyrighted books, a practice that's ethically and legally fraught on its own. No -- it cut the book pages out from their bindings, scanned them to make digital files, then threw away all those millions of pages of the original texts. To say that the AI "devoured" these books wouldn't merely be colorful language. This practice was revealed in a copyright ruling on Monday, which turned out to be a major win for Anthropic and the data-voracious tech industry at large. The judge presiding over the case, US district judge William Alsup, found that Anthropic can train its large language models on books that it bought legally, even without authors' explicit permission. It's a decision that owes, in part, to Anthropic's method of destructive book scanning -- which it's far from the first company to use, according to Ars, but is notable for its massive scale. In sum, it takes advantage of a legal concept known as the first-sale doctrine, which allows a buyer to do what they want with their purchase without the copyright holder intervening. This rule is what allows the secondhand market to exist -- otherwise a book's publisher, for example, might demand a cut or prevent their books from being resold. Leave it to AI companies, though, to use this in bad faith. According to the court filing, Anthropic hired former head of partnerships for Google's book-scanning project Tom Turvey in February 2024 to obtain "all the books in the world" without running into "legal/practice/business slog," as Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei described it, per the filing. Turvey came up with a workaround. By buying physical books, Anthropic would be protected by the first sale doctrine and would no longer have to obtain a license. Stripping the pages out allowed for cheaper and easier scanning. Since Anthropic only used the scanned books internally and tossed out the copies afterwards, the judge found this process to be akin to "conserv[ing] space," Ars noted, meaning it was transformative. Ergo, it's legally OK. It's a specious workaround and flagrantly hypocritical, of course. When Anthropic first got up and running, the startup went the even more unscrupulous route of downloading millions of pirated books to feed its AI. Meta did this with millions of pirated books, too, for which it is currently getting sued by a group of authors. It's also lazy and careless. As Ars notes, plenty of archivists have pioneered various approaches for scanning books en masse without having to destroy or alter the originals, including the Internet Archive and Google's own Google Books (which not too long ago was also the subject of its own major copyright battle.) But anything to save a few bucks -- and to get that all too precious training data. Indeed, the AI industry is running out of high quality sources of food to feeds its AI -- not least of all because it's short-sightedly spent this whole time crapping where it eats -- so screwing over some authors and sending some books to the shredder is, for Big Tech, a small price to pay.

[4]

Anthropic trashed millions of books to train its AI

Anthropic physically scanned millions of print books to train its AI assistant, Claude, subsequently discarding the originals, as revealed in court documents, according to Ars Tecnica. This extensive operation, detailed in a legal decision, involved the acquisition and destructive digitization of these texts. The company's approach to data acquisition reflects a broader industry demand for high-quality textual information. Anthropic engaged Tom Turvey, formerly the head of partnerships for Google Books, in February 2024. His mandate was to procure "all the books in the world" for the company. This hiring decision aimed to replicate Google's legally validated book digitization strategy, which had successfully navigated copyright challenges and established fair use precedents. While destructive scanning is common in smaller-scale operations, Anthropic implemented it on a massive scale. The destructive process offered faster speed and lower costs, outweighing the need to preserve the physical books. Judge William Alsup ruled this destructive scanning operation constituted fair use. This determination was contingent on several factors: Anthropic legally purchased the books, destroyed each print copy post-scanning, and maintained the digital files internally without distribution. The judge analogized the process to "conserv[ing] space" through format conversion, deeming it transformative. Had this method been consistently applied from the outset, it might have established the first legally sanctioned instance of AI fair use. However, Anthropic's earlier use of pirated material undermined its initial legal standing. The AI industry exhibits a significant demand for high-quality text, which serves as a fundamental driver behind these data acquisition strategies. Large language models (LLMs), such as those powering Claude and ChatGPT, are trained by ingesting billions of words into neural networks. During this training, the AI system processes the text repeatedly, establishing statistical relationships between words and concepts. The quality of the training data directly influences the capabilities of the resulting AI model. Models trained on well-edited books and articles generally produce more coherent and accurate responses compared to those trained on lower-quality text sources. Publishers retain legal control over content that AI companies seek for training purposes. Negotiating licenses for this content can be complex and time-consuming. The first-sale doctrine provided a legal workaround for Anthropic: once a physical book is purchased, the buyer can dispose of that specific copy, including destroying it. This principle allowed for the legal acquisition of physical books, circumventing direct licensing negotiations. Despite the legality, the procurement of physical books represented a substantial financial outlay. Initially, Anthropic opted to use digitized versions of pirated books to acquire high-quality training data, a strategy chosen to avoid what CEO Dario Amodei termed the "legal/practice/business slog" of complex licensing negotiations. By 2024, however, Anthropic had become "not so gung ho about" utilizing pirated ebooks due to "legal reasons," necessitating a more secure source of data. Purchasing used physical books offered a method to bypass licensing issues entirely while providing the professionally edited text essential for AI model training. Destructive scanning facilitated the rapid digitization of millions of volumes. Anthropic invested "many millions of dollars" in this book buying and scanning operation. The company often acquired used books in bulk. The process involved stripping books from their bindings, cutting pages to workable dimensions, and scanning them as stacks of pages into PDFs. These PDFs included machine-readable text and covers. All paper originals were subsequently discarded. Court documents do not indicate that any rare books were destroyed, as Anthropic procured its books in bulk from major retailers. Other methods exist for extracting information from paper while preserving the physical documents; for example, The Internet Archive developed non-destructive book scanning techniques that maintain the integrity of physical volumes while creating digital copies. In a related development, OpenAI and Microsoft announced a collaboration with Harvard's libraries to train AI models using nearly 1 million public domain books, some dating back to the 15th century. These books are fully digitized but are preserved.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Anthropic, an AI company, destroyed millions of physical books to train its AI model Claude, sparking debates on data acquisition methods, copyright, and ethics in AI development.

Anthropic's Controversial Book Destruction

In a shocking revelation, court documents have exposed that AI company Anthropic engaged in the destruction of millions of physical books to train its AI model, Claude. This controversial practice, aimed at acquiring high-quality training data, has ignited debates on the ethics and legality of AI development methods

1

.

Source: Ars Technica

The Destructive Scanning Operation

Anthropic's approach involved purchasing millions of physical books, cutting them from their bindings, scanning them into digital files, and discarding the originals. This process, known as destructive scanning, was implemented on an unprecedented scale. The company hired Tom Turvey, former head of partnerships for Google Books, to spearhead this operation in February 2024

1

.Legal Implications and Fair Use Ruling

U.S. District Judge William Alsup ruled that Anthropic's destructive scanning operation qualified as fair use. This decision was based on several factors:

- Anthropic legally purchased the books

- Each print copy was destroyed after scanning

- Digital files were kept internally and not distributed

The judge compared the process to "conserving space" through format conversion and deemed it transformative

2

.AI Industry's Data Hunger

The case highlights the AI industry's insatiable appetite for high-quality text data. Large language models (LLMs) like Claude require billions of words for training, with the quality of input directly impacting the model's capabilities

1

.

Source: Futurism

Copyright Challenges and Workarounds

Anthropic's approach exploited the first-sale doctrine, which allows buyers to do what they want with their purchases without copyright holder intervention. This legal workaround enabled the company to avoid complex licensing negotiations with publishers

3

.Ethical Concerns and Alternatives

The destruction of millions of books has raised ethical concerns within the archival and literary communities. Alternative methods for mass book digitization exist, such as those pioneered by the Internet Archive, which preserve physical volumes while creating digital copies

1

.Related Stories

Industry-wide Implications

Anthropic's partial legal victory allows it to train AI models on copyrighted books without notifying original publishers or authors. This ruling could have far-reaching consequences for the AI industry, potentially removing a significant hurdle in AI development

2

.Ongoing Legal Battles

Despite this ruling, Anthropic still faces a copyright trial in December for its earlier use of pirated ebooks. The company could be ordered to pay up to $150,000 per pirated work

2

.Future of AI Training Data Acquisition

As the AI industry grapples with data scarcity and copyright issues, companies are exploring various approaches. OpenAI and Microsoft recently announced a collaboration with Harvard's libraries to train AI models on nearly 1 million public domain books, demonstrating a more ethically sound approach to data acquisition

4

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[4]

Related Stories

Authors Sue AI Company Anthropic Over Copyright Infringement

20 Aug 2024

Anthropic Faces Potential 'Business-Ending' Damages in Copyright Lawsuit Over Pirated Books Used for AI Training

29 Jul 2025•Business and Economy

Judges Side with AI Companies in Copyright Cases, but Leave Door Open for Future Challenges

25 Jun 2025•Policy and Regulation

Recent Highlights

1

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

2

Demis Hassabis predicts AGI in 5-8 years, sees new golden era transforming medicine and science

Technology

3

Nvidia and Meta forge massive chip deal as computing power demands reshape AI infrastructure

Technology