Study Reveals Alarming Link Between Computer Vision Research and Surveillance Technologies

7 Sources

7 Sources

[1]

Is AI powering Big Brother? Surveillance research is on the rise

AI research on computer vision is almost always used in ways that enable surveillance, according to a new Nature study. Computer vision is what allows driverless cars to navigate, automatic tagging of people's faces on social media, and the detection of cancerous cells, but many people have argued it could also power mass surveillance. The new study trawled through over 40,000 documents to discover that the vast majority of research in computer vision powers surveillance. Such technology could be used to secure borders and catch criminals, but researchers are concerned that this could impact democratic freedoms by allowing easy identification and tracking of people. The study could help empower those who want to protect people from being surveilled, by highlighting how this research is being conducted and used.

[2]

Wake up call for AI: computer-vision research increasingly used for surveillance

Imaging research in the popular field of computer vision almost always involves analysing humans and their environments, and most of the subsequent patents can be used in surveillance technologies, a study has found. Computer-vision research involves developing algorithms to extract information from images and videos. It can be used to spot cancerous cells, classify animal species or in robot vision. But much of the time, the technologies are used to identify and track people, suggests the study published in Nature on 25 June. Computer scientists need to "wake up" and consider the moral implications of their work, says Yves Moreau, a computational biologist at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, who studies the ethics of human data. Human-surveillance technologies have advanced in the past few years with the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) and imaging capabilities. The technologies can recognize humans and their behaviour, for instance, through face or gait recognition and monitoring for certain actions. Police forces and governments say that AI-powered surveillance allows them to better protect the public. But critics say that the systems are prone to error, disproportionately affect minority populations and can be used to suppress protest. The analysis assessed 19,000 computer-vision papers published between 1990 and 2020 at the leading Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, as well as 23,000 patents that cited them. The researchers looked in depth at a random sample of 100 papers and 100 patents and found that 90% of the studies and 86% of the patents that cited those papers involved data relating to imaging humans and their spaces. Just 1% of the papers and 1% of the patents were designed to extract only non-human data. And the trend has increased. In a wider analysis the researchers searched all the patents for a list of keywords linked to surveillance, such as 'iris', 'criminal' and 'facial recognition'. They found that in the 2010s, 78% of computer-vision papers that led to patents produced ones related to surveillance, compared with 53% in the 1990s (see 'Surveillance-enabling research'). Almost "the entire field is working on faces and gaits, on detecting people in images, and nobody seems to be saying, 'wait what are we doing here?'" says Moreau. Although many have assumed that there was a pipeline from computer-vision research to surveillance, that is "very different than having actual empirical evidence", says Sandra Wachter, who studies technology and regulation at the University of Oxford, UK. The team also analysed the language used in papers and noted that researchers often described humans as 'objects' and social spaces that people inhabit as 'scenes'. "Compared to 'tracking people', 'following objects' doesn't have the same emotional load," says Moreau. This obfuscation can mean that ethics committees and researchers building on the work don't adhere to the ethical standards that they should when using human data, he adds. The researchers also looked at who is publishing papers that generate surveillance-related patents. Microsoft, headquartered in Redmond, Washington, published the largest number of papers that spawned patents that enable surveillance, at 296, followed by Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with 184 (see 'Papers leading to patents'). The organizations that enable or conduct surveillance tend to be "nations or companies or institutions that are extremely privileged, extremely powerful", says co-author Abeba Birhane, a cognitive scientist researching ethical AI at Trinity College Dublin. But the public has "very little input in what kind of surveillance technologies are used", she says. Scientists need more ethics education, says Wachter. Like a knife, the ability to extract data from images is not inherently good or bad, but it can be used in different ways, she adds. "The knife can be used to cut bread, or you can stab somebody with it. And it's the job of policymakers to make sure that we feed people and not stab them."

[3]

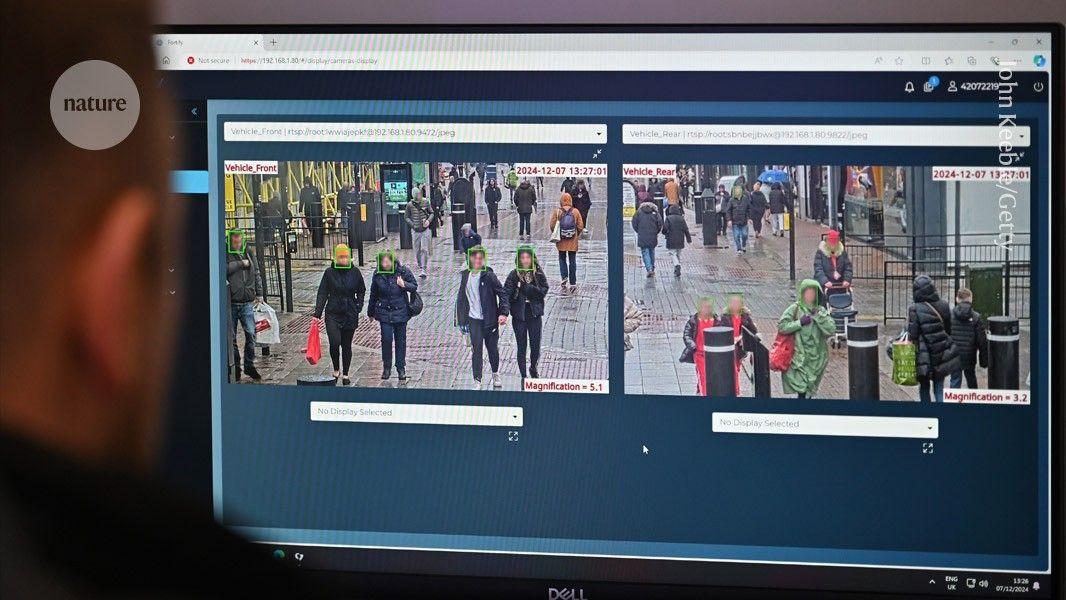

Don't sleepwalk from computer-vision research into surveillance

The nature of scientific progress is that it sometimes provides powerful tools that can be wielded for good or for ill: splitting the atom and nuclear weapons being a case in point. In such cases, it's necessary that researchers involved in developing such technologies participate actively in the ethical and political discussions about the appropriate boundaries for their use. Computer vision is one area in which more voices need to be heard. This week in Nature, Pratyusha Ria Kalluri, a computer scientist at Stanford University in California, and her colleagues analysed 19,000 papers published between 1990 and 2020 by the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) -- a prestigious event in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) concerned with extracting meaning from images and video. Studying a random sample, the researchers found that 90% of the papers and 86% of the patents that cited those articles involved imaging humans and their spaces (P. R. Kalluri et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08972-6; 2025). Just 1% of papers and 1% of patents involved only non-human data. This study backs up with clear evidence what many have long suspected: that computer-vision research is being used mainly in surveillance-enabling applications. The researchers also found that papers involving analysis of humans often refer to them as 'objects', which obfuscates how such research might ultimately be applied, the authors say. This should give researchers in the field cause to interrogate how, where and by whom their research will be applied. Regulators and policymakers bear ultimate responsibility for controlling the use of surveillance technology. But researchers have power too, and should not hesitate to use it. The time for these discussions is now. Computer vision has applications ranging from spotting cancer cells in medical images to mapping land use in satellite photos. There are now other possibilities that few researchers could once have dreamed of -- such as real-time analysis of activities that combines visual, audio and text data. These can be applied with good intentions: in driverless cars, facial recognition for mobile-phone security, flagging suspicious behaviour at airports or identifying banned fans at sports events. This summer, however, will see the expanding use of live facial-recognition cameras in London; these match faces to a police watch list in real time. Hong Kong is also installing similar cameras in its public spaces. London's police force say that its officers will physically be present where cameras are in operation, and will answer questions from the public. Biometric data from anyone who does not have a match on the list will be wiped immediately. But AI-powered systems can be prone to error, including biases introduced by human users, meaning that the people already most disempowered in society are also the most likely to be disadvantaged by surveillance. And, ethical concerns have been raised. In 2019, there was backlash when AI training data concerning real people were found to have been created without their consent. There was one such case at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, involving two million video frames of footage of students on campus. Others raised the alarm that computer-vision algorithms were being used to target vulnerable communities. Since then, computer-science conferences, including CVPR and NeurIPS, which focuses on machine learning, have added guidelines that submissions must adhere to ethical standards, including taking special precautions around human-derived data. But the impact of this is unclear. According to a study from Kevin McKee at Google DeepMind, based in London, less than one-quarter of papers involving the collection of original human data, submitted to two prominent AI conferences, outlined that they had applied appropriate standards, such as independent ethical review or informed consent (K. R. McKee IEEE-TTS 5, 279-288; 2024). Duke's now-retracted data set still racks up hundreds of mentions in research papers each year. Science that can help to catch criminals, secure national borders and prevent theft can also be used to monitor political groups, suppress protest and identify battlefield targets. Laws governing surveillance technologies must respect fundamental rights to privacy and freedom, core to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In many countries, legislation around surveillance technologies is patchy, and the conditions surrounding consent often lie in a legal grey area. As political and industry leaders continue to promote surveillance technologies, there will be less space for criticism, or even critical analysis, of their planned laws and policies. For example, in 2019, San Francisco, California, became the first US city to ban police use of facial recognition. But last year, its residents voted to boost the ability of its police force to use surveillance technologies. Earlier this year, the UK government renamed its AI Safety Institute; it became the AI Security Institute. Some researchers say that a war in Europe and a US president who supports 'big tech' have shifted the cultural winds. For Yves Moreau, a computational biologist at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium who studies the ethics of human data, the rise of surveillance is an example of 'technological somnambulism', in which humans sleepwalk into use of a technology without much reflection. Publishers should enforce their own ethical standards. Computer-vision researchers should refer to humans as humans, making clear to all the possible scope of their research's use. Scientists should consider their own personal ethics and use them to guide what they work on. Science organizations should speak out on what is or is not acceptable. "In my own work around misuse of forensic genetics, I have found that entering the social debate and saying 'this is not what we meant this technology for', this has an impact," says Moreau. Reflection must happen now.

[4]

Computer-vision research is hiding its role in creating 'Big Brother' technologies

You have full access to this article via Jozef Stefan Institute. We are in the middle of a huge boom in artificial intelligence (AI), with unprecedented investment in research, a supercharged pace of innovation and sky-high expectations. But what is driving this boom? Kalluri et al. provide an answer, at least for the sector of computer vision, in which machines automatically glean information from static and moving images. Their map of computer-vision research reveals an intimate relationship between academic research and surveillance applications created for the military, the police and profit-driven corporations. Many uses of 'surveillance' are relatively unexceptionable. As well as identifying cats on the Internet or automatically tagging your friends in photos on social media, computer vision is a crucial technology, for example, in autonomous vehicles that need to navigate roads, warehouses, mines or farms. It's also used in sport to track balls, assess player performance and detect goal-scoring. More controversially, computer vision also powers object- and facial-recognition systems that are widely used by police, banks, workplaces, shops, and many others for public security, tracking consumer behaviour or monitoring worker performance (Fig. 1). And the growing military interest in such technologies is undeniable. Venture capitalists are investing heavily in the defence sector, with much of that growth driven by funding for AI systems. Three powerhouse firms in the AI industry -- OpenAI, Palantir Technologies and Anduril Industries -- have joined together to secure lucrative contracts to build hardware and software for the US Departments of Defense and Homeland Security. These systems include AI-powered surveillance towers with automated recognition that can guide semi-autonomous drones to track and destroy targets. Kalluri and colleagues characterize the ever-deeper partnerships between computer-vision research and the technology industry and military and policing institutions as the "surveillance AI pipeline". They create a lexicon of more than 30 surveillance-indicator keywords -- explicit terms such as 'surveillance' or 'facial recognition', as well as words pointing to the human anatomy such as 'limb' and 'irises' and references to human characteristics such as gender and ethnicity. They analyse the occurrence of such terms in more than 19,000 papers published in the proceedings of the annual Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, and more than 23,000 downstream patents citing those papers. When compared with the widely used h5-index of citation impact, these conference proceedings rank among the highest-impact publications across all disciplines, sitting alongside Nature, Science and The New England Journal of Medicine. The authors find that "90% of papers and 86% of downstream patents extracted data relating to humans", with most explicitly using data about human bodies (for example, whole bodies or specific parts such as faces or gaits) and human spaces (including homes, shops and offices). The remaining portion of papers described their work in generic terms such as capturing images or analysing text, without stating whether these broad categories could also include human data. The study provides a striking overview of how works that "prioritize intrusive forms of data extraction" dominate computer-vision research. Kalluri et al. underscore the obfuscatory use of language in the field through a manual analysis of 100 computer-vision papers and 100 downstream patents from 2010 to 2020. Even when humans are clearly the subject of the surveillance, they are referred to as 'objects' -- a generic term that might include cars, cats, trees, tables and so on. Similarly, social spaces under surveillance are just referred to by the generic term 'scene'. All things being equal, these practices might be treated as a problem of semantics. Referring to humans as objects might be waved away as just engineering shorthand, and the generic tendency to create technologies that can be used to track any object of interest might be framed as necessary for patent applications. But all things are not equal, and such ubiquitous practices of dehumanization cannot be lightly dismissed. These technologies are created in a political and economic landscape in which the interests of massive corporations and military and policing institutions have a huge influence over the design and use of AI systems. I would argue that computer vision's focus on human data extraction does not merely coincide with these powerful interests, but rather is driven by them. The language surrounding this research is a powerful form of object-oriented obfuscation that abstracts any potential issues related to critical inquiry, ethical responsibility or political controversy. Overall, this research by Kalluri and colleagues represents an impressive mixture of computational, quantitative, manual and qualitative content analysis. I'm especially impressed by the line-by-line analysis of papers and patents by the team. This is a labour- and time-intensive approach that is unusual, particularly when dealing with dense, technical documents. What's even rarer is that different members of the research team, with disciplinary expertise spanning the technical and social sciences, analysed the same documents to ensure comprehensive, consistent findings. The paper's conclusions are rigorously supported and convincingly stated. Are other relevant fields also part of the surveillance AI pipeline? This point is not tackled in this analysis, but the existing literature points to the answer being yes: many subfields of AI are also involved in creating surveillance applications focused on capturing and analysing non-visual features of our world. These include tools focusing on text (Anthropic's Claude), audio (OpenAI's Whisper) and social-network data (Palantir's Gotham). Humans and their social world are being made machine-readable in a vast number of ways that include but go beyond visual inputs. Kalluri and colleagues have provided invaluable work that maps a highly influential and growing segment of the surveillance AI pipeline. Future research needs to study other segments. That should be the foundation for even more critical forms of inquiry and policy focused on blocking the pipeline that supplies the military-industrial surveillance complex with such powerful systems.

[5]

Surveillance-linked computer vision patents jump 5×

A new study shows academic computer vision papers feeding surveillance-enabling patents jumped more than fivefold from the 1990s to the 2010s. The researchers, including Stanford University's Pratyusha Ria Kalluri and Trinity College Dublin's Abeba Birhane, collected more than 19,000 research papers and more than 23,000 patents. In a manual content analysis of 100 computer-vision papers and 100 citing patents, they report that 90 percent of the papers, and 86 percent of the patents, extracted data relating to humans. The survey of academic research, published this week in the journal Nature, found that ambiguous language sometimes masked the surveillance implications of the research by referring to humans as objects. "Through an analysis of computer-vision research papers and citing patents, we found that most of these documents enable the targeting of human bodies and body parts," it said. Far from a few rogue researchers, the study found that "the normalization of targeting humans permeates the field. This normalization is especially striking given patterns of obfuscation. "We reveal obfuscating language that allows documents to avoid direct mention of targeting humans, for example, by normalizing the referring to of humans as 'objects' to be studied without special consideration. Our results indicate the extensive ties between computer-vision research and surveillance," the researchers wrote. In an accompanying article, Jathan Sadowski of Monash University in Melbourne argued it was unlikely to be coincidental that computer vision research ended up serving the needs of military, police, or corporate surveillance. "These technologies are created in a political and economic landscape in which the interests of massive corporations and military and policing institutions have a huge influence over the design and use of AI systems," he wrote. Furthermore, "I would argue that computer vision's focus on human data extraction does not merely coincide with these powerful interests, but rather is driven by them. The language surrounding this research is a powerful form of object-oriented obfuscation that abstracts any potential issues related to critical inquiry, ethical responsibility, or political controversy," he added. Sadowski argued the research should underpin more critical forms of inquiry and policy "focused on blocking the pipeline that supplies the military-industrial surveillance complex with such powerful systems." ®

[6]

Pervasive surveillance of people is being used to access, monetize, coerce and control, study suggests

New research has underlined the surprising extent to which pervasive surveillance of people and their habits is powered by computer vision research -- and shone a spotlight on how vulnerable individuals and communities are at risk. Analyses of over 40,000 documents, computer vision (CV) papers and downstream patents spanning four decades has shown a five-fold increase in the number of computer vision papers linked to downstream surveillance patents. The work also highlights the rise of obfuscating language that is used to normalize and even hide the existence of surveillance. The research, conducted by Dr. Abeba Birhane and collaborators from Stanford University, Carnegie Mellon University, University of Washington and the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence (AI2), has been published in Nature. Dr. Birhane directs the AI Accountability Lab (AIAL) in the ADAPT Research Ireland Center at the School of Computer Science and Statistics in Trinity College Dublin. Dr. Birhane said, "This work provides a detailed, systematic understanding of the field of computer vision research and presents a concrete empirical account that reveals the pathway from such research to surveillance and the extent of this surveillance." "While the general narrative is that only a small portion of computer vision research is harmful, what we found instead is pervasive and normalized surveillance." Among the key findings were that: Additionally, the work indicated the top institutions producing the most surveillance are: Microsoft; Carnegie Mellon University; MIT; University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; Chinese University of Hong Kong, and the top nations are: US; China; UK. Dr. Birhane added, "Linguistically, the field has increasingly adapted to obfuscate the existence and extent of surveillance. One such example is how the word 'object' has been normalized as an umbrella term which is often synonymous with 'people.'" "The most troublesome implications of this are that it is harder and harder to opt out, disconnect, or to 'just be,' and that tech and applications that come from this surveillance are often used to access, monetize, coerce, and control individuals and communities at the margins of society. "Due to pervasive and intensive data gathering and surveillance, our rights to privacy and related freedoms of movement, speech and expression are under significant threat." However, the researchers stress that a major, more hopeful takeaway from the work is that nothing is written in stone, and that this large-scale, systematic study can aid regulators and policy makers in addressing some of the issues. Dr. Birhane said, "We hope these findings will equip activists and grassroots communities with the empirical evidence they need to demand change, and to help transform systems and societies in a more rights-respecting direction." "CV researchers could also adopt a more critical approach, exercise the right to conscientious objection, collectively protest and cancel surveillance projects, and change their focus to study ethical dimensions of the field, educate the public, or put forward informed advocacy."

[7]

New study finds dramatic rise in 'pervasive surveillance'

The US, China and the UK are the top three global producers of surveillance, finds the study. An analysis of more than 40,000 documents and patents spanning four decades reveals a five-fold increase in the number of computer vision (CV) papers relating to downstream surveillance patents. Governments can use tech companies to access specific user communications. This method of accessing data is referred to as downstream intelligence. The research finds that CV, a form of AI that can train computers to emulate how humans see, is being used to conduct "pervasive surveillance of people". The study, published in Nature Magazine, finds that the US, China and the UK are the top three global producers of surveillance, while Microsoft, Carnegie Mellon University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are ranked as the top three institutions conducting such activities. The joint research was conducted by Dr Abeba Birhane, the director of AI Accountability Lab (AIAL) in the ADAPT Research Centre in Trinity College of Dublin, along with collaborators from Stanford University, Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Washington and Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence. "While the general narrative is that only a small portion of Computer Vision research is harmful, what we found instead is pervasive and normalised surveillance," Dr Birhane said. The new research also finds a concerning rise in language that normalises the existence of surveillance. By analysing thousands of documents, CV papers and downstream patents - or patents that build upon existing tech - the study found that surveillance is increasingly being hidden through this distracting language. "Linguistically the field has increasingly adapted to obfuscate the existence and extent of surveillance," Dr Birhane said. "One such example is how the word 'object' has been normalised as an umbrella term which is often synonymous with 'people'." She adds that the nature of pervasive and intensive data gathering and surveillance has put our rights to privacy and the freedom of movement, speech and expression under "significant threat". According to her, the most troublesome implication of this is the increasing difficulty of being able to "opt out, disconnect or just be". "Tech and applications that come from this surveillance are often used to access, monetise, coerce and control individuals and communities at the margins of society," Dr Birhane added. Although, the study finds a caveat. The researchers stress that regulators and policy makers can address some of the issues. "We hope these findings will equip activists and grassroots communities with the empirical evidence they need to demand change, and to help transform systems and societies in a more rights-respecting direction," the AIAL director said. She also hopes that CV researchers could adopt a more "critical" approach, exercise the right to conscientious objection, collectively protest and cancel surveillance projects. The AIAL was launched late last year, putting Birhane, who was ranked by Time Magazine as one in 100 most influential people in AI in 2023, at its helm. The lab works towards addressing the structural inequalities and transparency issues related to AI deployment. In 2023, Birhane was also appointed to a United National AI advisory body aimed at supporting global efforts to govern AI. In an interview with SiliconRepublic.com, Birhane rang warning bells around hyping up generative AI, highlighting issues around hallucinations and biases. Don't miss out on the knowledge you need to succeed. Sign up for the Daily Brief, Silicon Republic's digest of need-to-know sci-tech news.

Share

Share

Copy Link

A new study published in Nature exposes the strong connection between academic computer vision research and surveillance applications, raising ethical concerns about AI's role in mass surveillance.

Study Uncovers Pervasive Link Between Computer Vision Research and Surveillance

A groundbreaking study published in Nature has revealed an alarming connection between academic computer vision research and surveillance technologies. The research, conducted by a team including Pratyusha Ria Kalluri from Stanford University and Abeba Birhane from Trinity College Dublin, analyzed over 19,000 computer vision papers and 23,000 related patents

1

.

Source: The Register

Key Findings

The study's most striking discovery was that 90% of the analyzed papers and 86% of the citing patents involved data extraction relating to humans and their environments

2

. This trend has significantly increased over time, with 78% of computer vision papers in the 2010s leading to surveillance-related patents, compared to 53% in the 1990s.Obfuscation in Research Language

Researchers found a concerning pattern of language use in computer vision papers. Humans were often referred to as "objects," and social spaces as "scenes," potentially obscuring the ethical implications of the research

3

. This obfuscation could lead to ethics committees and researchers overlooking important ethical considerations when dealing with human data.Major Contributors to Surveillance-Enabling Research

Source: Nature

The study identified key organizations contributing to surveillance-enabling research:

- Microsoft: 296 papers leading to surveillance-related patents

- Carnegie Mellon University: 184 papers

2

Ethical Concerns and Implications

While computer vision has beneficial applications in areas such as medical imaging and autonomous vehicles, its potential for mass surveillance raises significant ethical concerns. Critics argue that AI-powered surveillance systems can be prone to errors, disproportionately affect minority populations, and potentially suppress democratic freedoms

4

.Related Stories

The "Surveillance AI Pipeline"

Jathan Sadowski of Monash University suggests that the focus on human data extraction in computer vision research is driven by the interests of corporations, military, and policing institutions. He describes this as the "surveillance AI pipeline," highlighting the deep partnerships between academic research and surveillance applications

5

.

Source: Nature

Call for Ethical Consideration and Regulation

The study's authors and commentators emphasize the need for researchers to actively participate in ethical and political discussions about the appropriate boundaries for their work. They call for:

- Enforced ethical standards by publishers

- Clear language in research papers about potential applications

- Personal ethical considerations by scientists

- Advocacy from scientific organizations on acceptable practices

3

As AI and computer vision technologies continue to advance, the debate over their ethical use in surveillance is likely to intensify, demanding increased scrutiny and regulation from policymakers and the scientific community alike.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[5]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens to cut Anthropic's $200M contract over AI safety restrictions in military ops

Policy and Regulation

2

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI closes in on $100 billion funding round with $850 billion valuation as spending plans shift

Business and Economy