License Plate Readers in Michigan Ignite Privacy Concerns as Communities Push Back

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Michigan license plate cameras face backlash: Big help, or Big Brother?

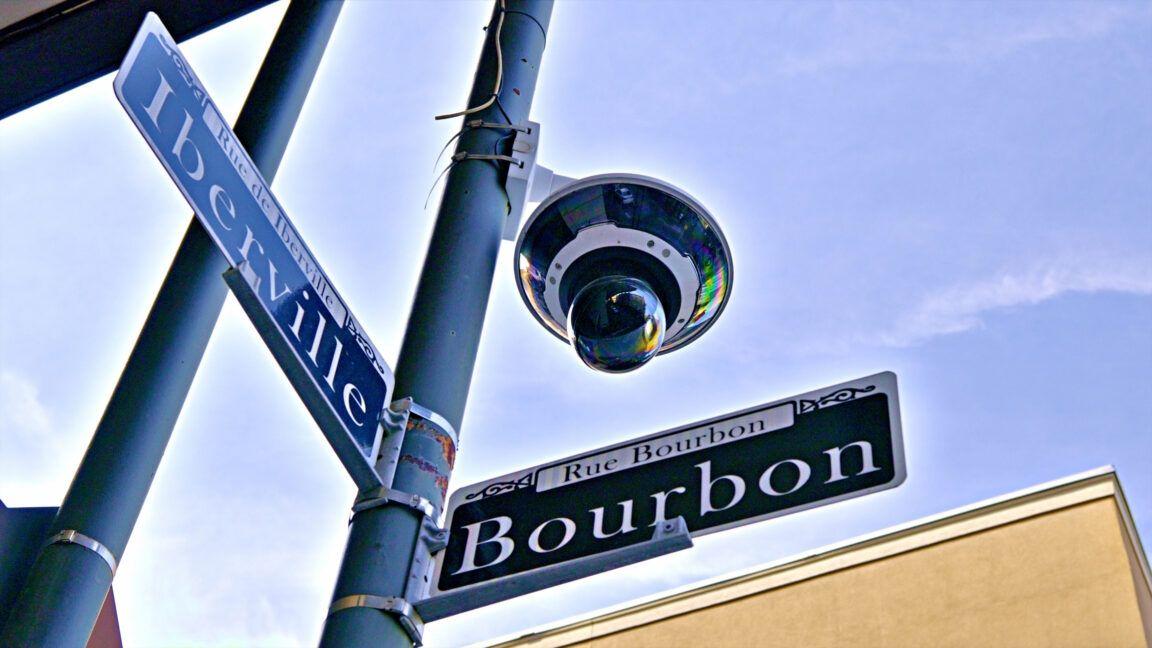

In more than 125 cities and counties across Michigan, nondescript cameras perched near busy roadways snap a picture every time a car drives by. The cameras -- automated license plate readers primarily operated under contract with Flock Safety of Atlanta -- are touted by law enforcement agencies as a speedy way to help locate missing people or catch criminals. But privacy advocates and citizens in communities large and small are increasingly raising concerns, arguing the technology infringes on citizens' privacy rights, relies too heavily on artificial intelligence and can lead to data getting shared well beyond local boundary lines. Those concerns have ramped up in recent months amid the Trump administration's aggressive deportation campaign. Flock has said it does not directly share data with any federal agency, but system lookup data analyzed last year by 404 Media showed local and state police across the country have frequently performed searches for federal partners, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). "I see this as one big, slippery slope," retired attorney Linda Berker told the Lapeer County Commission last week as officials considered allowing its sheriff's department to purchase license plate readers. "I know we have a right to safety, but what about privacy, and what about the right to go wherever you want, whenever you want, without the government tracking you?" Some cities, including Bay City and Ferndale, have in recent months backed out of contracts with Flock and are reassessing their use of license plate readers in response to community concerns. In Detroit, Police Chief Todd Bettison has said his agency is "not sharing data" with ICE, but city council members last week requested a report on how data collected from the city's more than 500 license plate readers is used, expressing concerns about the possibility of data sharing. But other communities are still considering getting their own license plate readers or adding onto existing contracts as local police credit the technology with helping locate stolen vehicles, bust human trafficking rings, solve serious crimes like rapes and murders and fill coverage gaps in short-staffed departments. "We do not spy on residents," Waterford Township Police Chief Scott Underwood told local officials during a Monday hearing. His department requested and received a three-year, $60,000 video integration add-on to its existing contract with Flock. "We use our Flock technology and all of our technology in a responsible, ethical way to investigate and solve crimes," he continued. In most communities with license plate readers, the devices are placed at or near major public intersections. As vehicles pass by, the reader takes a photo of the back of the car, collecting the license plate number that can be used to look up the vehicle registration. Photos are typically stored by the contractor for 30 days, though locals can elect to keep them for more or less time. The law enforcement entity can then cross-check those images with "hot lists" of license plates connected to suspected criminals or missing people. "The cameras get a photo of the back of the vehicle and license plate. There is no personally identifiable information," Kerry McCormack, a Flock representative and former Cleveland City Council member, recently told Lapeer County commissioners. "Who's driving the car, what they eat for breakfast, their Social Security number -- any attributes of the person are not captured by this camera." McCormack said Flock is designed to be a "force multiplier" to help police collaborate and do their jobs more efficiently. Contracting agencies can choose to share the collected data with other agencies nationally or limit data sharing to within their state or region, McCormack added, noting that the company takes the balance between privacy and public safety seriously. Separately, US Border Patrol has worked with technology companies to place its own license plate cameras in Michigan and other states, according to an Associated Press investigation. Critics contend that 24-hour surveillance of drivers, the vast majority of whom will never be charged with a crime, poses major privacy concerns. The 30-day standard for storing the data also means anyone with access could gain insight into a driver's daily routines, said Gabrielle Dresner, a policy strategist with the ACLU of Michigan. "That's an extensive amount of travel data that's being held on people just traversing the roadways, doing nothing wrong," Dresner said. "You can see a pattern of people's movements based on where their license plate crosses through." In Waterford Township, where police began using license plate readers in 2022, law enforcement is adding additional readers and Flock-powered drones to its repertoire, despite concerted pushback from locals. Township trustees on Monday also approved an updated agreement that includes Flock OS-Plus, a system that allows officers to integrate Flock footage with video from cruiser dashcams, body cameras and the Waterford School District. Other communities have attempted to mollify residents' concerns by seeking other options. Last November, the city of Ferndale ended its partnership with Flock amid significant public backlash to the pilot program that began in 2023. At the time, Ferndale Police Chief Dennis Emmi said the city would evaluate other potential vendors for license plate readers and aimed "to balance ethical standards with community expectations while equipping investigators with effective tools to solve crime." City officials in December tentatively approved a five-year contract with a different company, Axon, for license plate reader services. Emmi told Bridge Michigan that approval of the contract is contingent on the council passing a separate ordinance addressing privacy protections and city oversight of surveillance technology, scheduled to come up in February. In communities actively considering new or updated license plate reader contracts, much of the public criticism has centered around the possibility of data being used to surveil lawful activity or the possible sharing of data with federal law enforcement agencies, which do not contract with Flock but can request data from local police. Sarah Hamid, director of strategic campaigns for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for digital privacy rights, said community pushback against license plate readers "really exploded" starting in summer 2025 as reports emerged about the data being used for immigration-related searches, people seeking abortions and more. "All across the country, you're seeing this concerted effort to push these surveillance sensors out of their community as soon as possible," Hamid said. An Electronic Frontier Foundation analysis of nationwide searches on Flock servers found several instances of protest-related searches, including lookups from the Grand Rapids Police Department that corresponded with a February rally. A department spokesperson later told the Michigan Advance that police do not use the Flock devices to target protesters. In Lapeer County, commissioners remain split on whether to move forward with Flock cameras, opting to continue discussions next month. Sheriff Scott McKenna said he understands the reticence and respects local opinions. But he said the concerns are hard to square with the positive impacts he believes readers could have on the county, citing the technology's usefulness for finding elderly residents with dementia or tracking criminals hailing from outside county lines. "I've never seen a tool that's more beneficial for protecting the community than this one," he told commissioners. Commissioner Scott McMahan wasn't as convinced, expressing fears that for all the promises that data wouldn't be shared with federal agencies or other third parties, it may not end up being in the county's control. "We're talking about enabling a system that will be 24/7 surveilling all citizens, law-abiding, all of us, and storing that data," he said. "We're now expected to just take (Flock's) word for it that you're not sharing this." As public awareness of automated license plate readers grows, there's no exact blueprint or best practice for communities considering new license plate reader contracts or adding to existing ones. At least 16 states have adopted policies aimed at regulating the use and retention of data collected by license plate readers, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, though efforts in several states to beef up privacy protections failed to advance. Michigan has no state law on the books governing the readers, meaning the decision on how license plate readers are used comes down to a "patchwork of local policies," said Hamid of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "Cities aren't just the last line of defense against federal encroachment, they're also the first line of exposure through these data systems," Hamid said, adding that because agencies often share data across local boundaries, "community members really need to be asking hard questions about where their data actually flows." ___ This story was originally published by Bridge Michigan and distributed through a partnership with The Associated Press.

[2]

Michigan License Plate Cameras Face Backlash: Big Help, or Big Brother?

In more than 125 cities and counties across Michigan, nondescript cameras perched near busy roadways snap a picture every time a car drives by. The cameras -- automated license plate readers primarily operated under contract with Flock Safety of Atlanta -- are touted by law enforcement agencies as a speedy way to help locate missing people or catch criminals. But privacy advocates and citizens in communities large and small are increasingly raising concerns, arguing the technology infringes on citizens' privacy rights, relies too heavily on artificial intelligence and can lead to data getting shared well beyond local boundary lines. Those concerns have ramped up in recent months amid the Trump administration's aggressive deportation campaign. Flock has said it does not directly share data with any federal agency, but system lookup data analyzed last year by 404 Media showed local and state police across the country have frequently performed searches for federal partners, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). "I see this as one big, slippery slope," retired attorney Linda Berker told the Lapeer County Commission last week as officials considered allowing its sheriff's department to purchase license plate readers. "I know we have a right to safety, but what about privacy, and what about the right to go wherever you want, whenever you want, without the government tracking you?" Some cities, including Bay City and Ferndale, have in recent months backed out of contracts with Flock and are reassessing their use of license plate readers in response to community concerns. In Detroit, Police Chief Todd Bettison has said his agency is "not sharing data" with ICE, but city council members last week requested a report on how data collected from the city's more than 500 license plate readers is used, expressing concerns about the possibility of data sharing. But other communities are still considering getting their own license plate readers or adding onto existing contracts as local police credit the technology with helping locate stolen vehicles, bust human trafficking rings, solve serious crimes like rapes and murders and fill coverage gaps in short-staffed departments. "We do not spy on residents," Waterford Township Police Chief Scott Underwood told local officials during a Monday hearing. His department requested and received a three-year, $60,000 video integration add-on to its existing contract with Flock. "We use our Flock technology and all of our technology in a responsible, ethical way to investigate and solve crimes," he continued. 'Force multiplier' for police? In most communities with license plate readers, the devices are placed at or near major public intersections. As vehicles pass by, the reader takes a photo of the back of the car, collecting the license plate number that can be used to look up the vehicle registration. Photos are typically stored by the contractor for 30 days, though locals can elect to keep them for more or less time. The law enforcement entity can then cross-check those images with "hot lists" of license plates connected to suspected criminals or missing people. "The cameras get a photo of the back of the vehicle and license plate. There is no personally identifiable information," Kerry McCormack, a Flock representative and former Cleveland City Council member, recently told Lapeer County commissioners. "Who's driving the car, what they eat for breakfast, their Social Security number -- any attributes of the person are not captured by this camera." McCormack said Flock is designed to be a "force multiplier" to help police collaborate and do their jobs more efficiently. Contracting agencies can choose to share the collected data with other agencies nationally or limit data sharing to within their state or region, McCormack added, noting that the company takes the balance between privacy and public safety seriously. Separately, US Border Patrol has worked with technology companies to place its own license plate cameras in Michigan and other states, according to an Associated Press investigation. Critics contend that 24-hour surveillance of drivers, the vast majority of whom will never be charged with a crime, poses major privacy concerns. The 30-day standard for storing the data also means anyone with access could gain insight into a driver's daily routines, said Gabrielle Dresner, a policy strategist with the ACLU of Michigan. "That's an extensive amount of travel data that's being held on people just traversing the roadways, doing nothing wrong," Dresner said. "You can see a pattern of people's movements based on where their license plate crosses through." Differing approaches In Waterford Township, where police began using license plate readers in 2022, law enforcement is adding additional readers and Flock-powered drones to its repertoire, despite concerted pushback from locals. Township trustees on Monday also approved an updated agreement that includes Flock OS-Plus, a system that allows officers to integrate Flock footage with video from cruiser dashcams, body cameras and the Waterford School District. Other communities have attempted to mollify residents' concerns by seeking other options. Last November, the city of Ferndale ended its partnership with Flock amid significant public backlash to the pilot program that began in 2023. At the time, Ferndale Police Chief Dennis Emmi said the city would evaluate other potential vendors for license plate readers and aimed "to balance ethical standards with community expectations while equipping investigators with effective tools to solve crime." City officials in December tentatively approved a five-year contract with a different company, Axon, for license plate reader services. Emmi told Bridge Michigan that approval of the contract is contingent on the council passing a separate ordinance addressing privacy protections and city oversight of surveillance technology, scheduled to come up in February. In communities actively considering new or updated license plate reader contracts, much of the public criticism has centered around the possibility of data being used to surveil lawful activity or the possible sharing of data with federal law enforcement agencies, which do not contract with Flock but can request data from local police. Sarah Hamid, director of strategic campaigns for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for digital privacy rights, said community pushback against license plate readers "really exploded" starting in summer 2025 as reports emerged about the data being used for immigration-related searches, people seeking abortions and more. "All across the country, you're seeing this concerted effort to push these surveillance sensors out of their community as soon as possible," Hamid said. An Electronic Frontier Foundation analysis of nationwide searches on Flock servers found several instances of protest-related searches, including lookups from the Grand Rapids Police Department that corresponded with a February rally. A department spokesperson later told the Michigan Advance that police do not use the Flock devices to target protesters. Last line of defense, first line of exposure In Lapeer County, commissioners remain split on whether to move forward with Flock cameras, opting to continue discussions next month. Sheriff Scott McKenna said he understands the reticence and respects local opinions. But he said the concerns are hard to square with the positive impacts he believes readers could have on the county, citing the technology's usefulness for finding elderly residents with dementia or tracking criminals hailing from outside county lines. "I've never seen a tool that's more beneficial for protecting the community than this one," he told commissioners. Commissioner Scott McMahan wasn't as convinced, expressing fears that for all the promises that data wouldn't be shared with federal agencies or other third parties, it may not end up being in the county's control. "We're talking about enabling a system that will be 24/7 surveilling all citizens, law-abiding, all of us, and storing that data," he said. "We're now expected to just take (Flock's) word for it that you're not sharing this." As public awareness of automated license plate readers grows, there's no exact blueprint or best practice for communities considering new license plate reader contracts or adding to existing ones. At least 16 states have adopted policies aimed at regulating the use and retention of data collected by license plate readers, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, though efforts in several states to beef up privacy protections failed to advance. Michigan has no state law on the books governing the readers, meaning the decision on how license plate readers are used comes down to a "patchwork of local policies," said Hamid of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "Cities aren't just the last line of defense against federal encroachment, they're also the first line of exposure through these data systems," Hamid said, adding that because agencies often share data across local boundaries, "community members really need to be asking hard questions about where their data actually flows." ___ This story was originally published by Bridge Michigan and distributed through a partnership with The Associated Press.

Share

Share

Copy Link

More than 125 Michigan cities and counties have deployed automated license plate readers, primarily through Flock Safety contracts. While law enforcement agencies tout the technology for solving crimes and locating missing people, privacy advocates and citizens are raising alarms about surveillance overreach, data sharing with federal agencies including ICE, and the erosion of citizen privacy rights.

License Plate Readers Expand Across Michigan Amid Growing Controversy

More than 125 cities and counties across Michigan have installed automated license plate readers (ALPRs) that photograph every passing vehicle, creating a widespread surveillance network that has ignited fierce debate over public safety and individual privacy

1

. The cameras, primarily operated under contract with Flock Safety of Atlanta, are positioned near busy roadways and major intersections throughout the state. Law enforcement agencies promote these surveillance sensors as essential tools for locating missing people, recovering stolen vehicles, and solving serious crimes including human trafficking cases, rapes, and murders2

.Privacy Concerns Intensify Over Data Sharing Practices

The surveillance technology debate has intensified significantly in recent months amid the Trump administration's aggressive deportation campaign, raising alarm bells about data sharing with federal agencies. While Flock Safety maintains it does not directly share data with any federal agency, 404 Media's analysis of system lookup data revealed that local and state police across the country have frequently performed searches for federal partners, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

1

. This discovery has fueled community backlash against surveillance, with retired attorney Linda Berker telling the Lapeer County Commission: "I know we have a right to safety, but what about privacy, and what about the right to go wherever you want, whenever you want, without the government tracking you?"1

Communities Split on Automated Surveillance Systems

The response from Michigan communities has been sharply divided. Bay City and Ferndale have backed out of their Flock contracts in recent months and are reassessing their use of license plate readers in response to citizen privacy rights concerns

1

. In Detroit, where more than 500 license plate readers are deployed, Police Chief Todd Bettison has stated his agency is "not sharing data" with ICE, though city council members requested a detailed report on data usage amid mounting concerns1

. Meanwhile, Waterford Township approved a three-year, $60,000 video integration add-on to its existing Flock contract, with Police Chief Scott Underwood defending the technology: "We do not spy on residents. We use our Flock technology and all of our technology in a responsible, ethical way to investigate and solve crimes"2

.Related Stories

How the Technology Works and What Data Gets Collected

The automated license plate readers capture photographs of vehicle rear ends as they pass, collecting license plate numbers that can be cross-referenced with "hot lists" of plates connected to suspected criminals or missing people

2

. Photos are typically stored for 30 days through data retention policies, though local agencies can adjust this timeframe. Kerry McCormack, a Flock representative, emphasized that the cameras don't capture personally identifiable information beyond the license plate itself, describing the system as a "force multiplier" to help police collaborate more efficiently2

. Contracting agencies can choose to share collected data with other agencies nationally or limit sharing to their state or region.Privacy Advocates Warn of Big Brother Implications

Gabrielle Dresner, a policy strategist with the ACLU of Michigan, argues that the 30-day storage period enables extensive tracking of innocent citizens' movements. "That's an extensive amount of travel data that's being held on people just traversing the roadways, doing nothing wrong," Dresner explained. "You can see a pattern of people's movements based on where their license plate crosses through"

2

. This Big Brother scenario particularly troubles privacy advocates who note that the vast majority of photographed drivers will never be charged with a crime, yet their daily routines become visible to anyone with system access. The technology's reliance on artificial intelligence for processing and pattern recognition adds another layer of concern about accuracy and potential misuse. Community pushback has grown as residents question whether the benefits to law enforcement agencies justify the erosion of privacy in public spaces.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Border Patrol's AI-Powered Surveillance Network Monitors Millions of US Drivers

20 Nov 2025•Policy and Regulation

Federal agents deploy facial recognition tech in immigration crackdown, sparking privacy concerns

30 Jan 2026•Policy and Regulation

New Orleans Police Pause Controversial AI-Powered Facial Recognition Program Amid Privacy Concerns

20 May 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Samsung unveils Galaxy S26 lineup with Privacy Display tech and expanded AI capabilities

Technology

2

Anthropic refuses Pentagon's ultimatum over AI use in mass surveillance and autonomous weapons

Policy and Regulation

3

AI models deploy nuclear weapons in 95% of war games, raising alarm over military use

Science and Research