MIT Develops AI-Powered Robot Mapping System for Search-and-Rescue Operations

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Teaching robots to map large environments

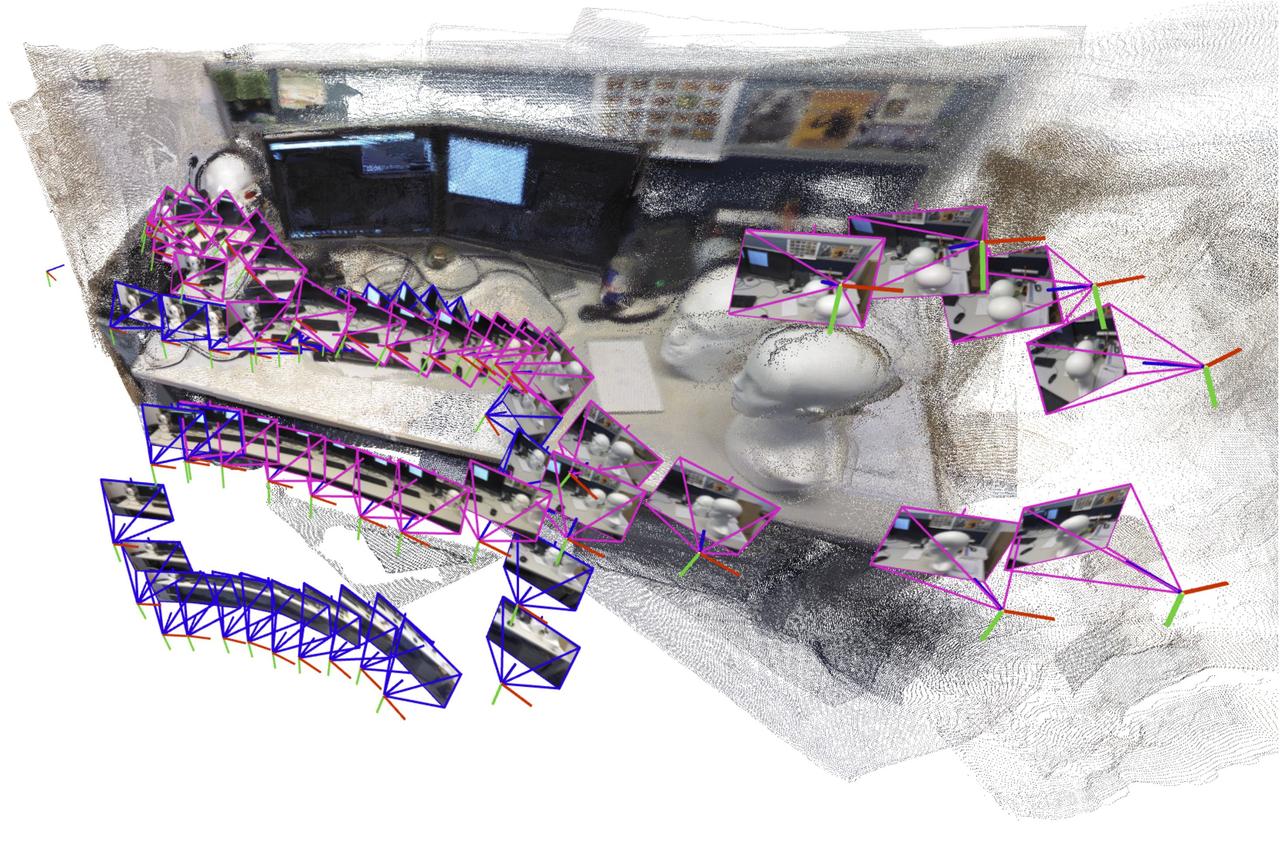

Caption: The artificial intelligence-driven system incrementally creates and aligns smaller submaps of the scene, which it stitches together to reconstruct a full 3D map, like of an office cubicle, while estimating the robot's position in real-time. A robot searching for workers trapped in a partially collapsed mine shaft must rapidly generate a map of the scene and identify its location within that scene as it navigates the treacherous terrain. Researchers have recently started building powerful machine-learning models to perform this complex task using only images from the robot's onboard cameras, but even the best models can only process a few images at a time. In a real-world disaster where every second counts, a search-and-rescue robot would need to quickly traverse large areas and process thousands of images to complete its mission. To overcome this problem, MIT researchers drew on ideas from both recent artificial intelligence vision models and classical computer vision to develop a new system that can process an arbitrary number of images. Their system accurately generates 3D maps of complicated scenes like a crowded office corridor in a matter of seconds. The AI-driven system incrementally creates and aligns smaller submaps of the scene, which it stitches together to reconstruct a full 3D map while estimating the robot's position in real-time. Unlike many other approaches, their technique does not require calibrated cameras or an expert to tune a complex system implementation. The simpler nature of their approach, coupled with the speed and quality of the 3D reconstructions, would make it easier to scale up for real-world applications. Beyond helping search-and-rescue robots navigate, this method could be used to make extended reality applications for wearable devices like VR headsets or enable industrial robots to quickly find and move goods inside a warehouse. "For robots to accomplish increasingly complex tasks, they need much more complex map representations of the world around them. But at the same time, we don't want to make it harder to implement these maps in practice. We've shown that it is possible to generate an accurate 3D reconstruction in a matter of seconds with a tool that works out of the box," says Dominic Maggio, an MIT graduate student and lead author of a paper on this method. Maggio is joined on the paper by postdoc Hyungtae Lim and senior author Luca Carlone, associate professor in MIT's Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro), principal investigator in the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems (LIDS), and director of the MIT SPARK Laboratory. The research will be presented at the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Mapping out a solution For years, researchers have been grappling with an essential element of robotic navigation called simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM). In SLAM, a robot recreates a map of its environment while orienting itself within the space. Traditional optimization methods for this task tend to fail in challenging scenes, or they require the robot's onboard cameras to be calibrated beforehand. To avoid these pitfalls, researchers train machine-learning models to learn this task from data. While they are simpler to implement, even the best models can only process about 60 camera images at a time, making them infeasible for applications where a robot needs to move quickly through a varied environment while processing thousands of images. To solve this problem, the MIT researchers designed a system that generates smaller submaps of the scene instead of the entire map. Their method "glues" these submaps together into one overall 3D reconstruction. The model is still only processing a few images at a time, but the system can recreate larger scenes much faster by stitching smaller submaps together. "This seemed like a very simple solution, but when I first tried it, I was surprised that it didn't work that well," Maggio says. Searching for an explanation, he dug into computer vision research papers from the 1980s and 1990s. Through this analysis, Maggio realized that errors in the way the machine-learning models process images made aligning submaps a more complex problem. Traditional methods align submaps by applying rotations and translations until they line up. But these new models can introduce some ambiguity into the submaps, which makes them harder to align. For instance, a 3D submap of a one side of a room might have walls that are slightly bent or stretched. Simply rotating and translating these deformed submaps to align them doesn't work. "We need to make sure all the submaps are deformed in a consistent way so we can align them well with each other," Carlone explains. A more flexible approach Borrowing ideas from classical computer vision, the researchers developed a more flexible, mathematical technique that can represent all the deformations in these submaps. By applying mathematical transformations to each submap, this more flexible method can align them in a way that addresses the ambiguity. Based on input images, the system outputs a 3D reconstruction of the scene and estimates of the camera locations, which the robot would use to localize itself in the space. "Once Dominic had the intuition to bridge these two worlds -- learning-based approaches and traditional optimization methods -- the implementation was fairly straightforward," Carlone says. "Coming up with something this effective and simple has potential for a lot of applications. Their system performed faster with less reconstruction error than other methods, without requiring special cameras or additional tools to process data. The researchers generated close-to-real-time 3D reconstructions of complex scenes like the inside of the MIT Chapel using only short videos captured on a cell phone. The average error in these 3D reconstructions was less than 5 centimeters. In the future, the researchers want to make their method more reliable for especially complicated scenes and work toward implementing it on real robots in challenging settings. "Knowing about traditional geometry pays off. If you understand deeply what is going on in the model, you can get much better results and make things much more scalable," Carlone says. This work is supported, in part, by the U.S. National Science Foundation, U.S. Office of Naval Research, and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Carlone, currently on sabbatical as an Amazon Scholar, completed this work before he joined Amazon.

[2]

Flexible mapping technique can help search-and-rescue robots navigate unpredictable environments

A robot searching for workers trapped in a partially collapsed mine shaft must rapidly generate a map of the scene and identify its location within that scene as it navigates the treacherous terrain. Researchers have recently started building powerful machine-learning models to perform this complex task using only images from the robot's onboard cameras, but even the best models can only process a few images at a time. In a real-world disaster where every second counts, a search-and-rescue robot would need to quickly traverse large areas and process thousands of images to complete its mission. To overcome this problem, MIT researchers drew on ideas from both recent artificial intelligence vision models and classical computer vision to develop a new system that can process an arbitrary number of images. Their system accurately generates 3D maps of complicated scenes like a crowded office corridor in a matter of seconds. The AI-driven system incrementally creates and aligns smaller submaps of the scene, which it stitches together to reconstruct a full 3D map while estimating the robot's position in real-time. Unlike many other approaches, their technique does not require calibrated cameras or an expert to tune a complex system implementation. The simpler nature of their approach, coupled with the speed and quality of the 3D reconstructions, would make it easier to scale up for real-world applications. Beyond helping search-and-rescue robots navigate, this method could be used to make extended reality applications for wearable devices like VR headsets or enable industrial robots to quickly find and move goods inside a warehouse. "For robots to accomplish increasingly complex tasks, they need much more complex map representations of the world around them. But at the same time, we don't want to make it harder to implement these maps in practice. We've shown that it is possible to generate an accurate 3D reconstruction in a matter of seconds with a tool that works out of the box," says Dominic Maggio, an MIT graduate student and lead author of a paper on this method. Maggio is joined on the paper by postdoc Hyungtae Lim and senior author Luca Carlone, associate professor in MIT's Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro), principal investigator in the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems (LIDS), and director of the MIT SPARK Laboratory. The research will be presented at the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. The findings are published on the arXiv preprint server. Mapping out a solution For years, researchers have been grappling with an essential element of robotic navigation called simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM). In SLAM, a robot recreates a map of its environment while orienting itself within the space. Traditional optimization methods for this task tend to fail in challenging scenes, or they require the robot's onboard cameras to be calibrated beforehand. To avoid these pitfalls, researchers train machine-learning models to learn this task from data. While they are simpler to implement, even the best models can only process about 60 camera images at a time, making them infeasible for applications where a robot needs to move quickly through a varied environment while processing thousands of images. To solve this problem, the MIT researchers designed a system that generates smaller submaps of the scene instead of the entire map. Their method "glues" these submaps together into one overall 3D reconstruction. The model is still only processing a few images at a time, but the system can recreate larger scenes much faster by stitching smaller submaps together. "This seemed like a very simple solution, but when I first tried it, I was surprised that it didn't work that well," Maggio says. Searching for an explanation, he dug into computer vision research papers from the 1980s and 1990s. Through this analysis, Maggio realized that errors in the way the machine-learning models process images made aligning submaps a more complex problem. Traditional methods align submaps by applying rotations and translations until they line up. But these new models can introduce some ambiguity into the submaps, which makes them harder to align. For instance, a 3D submap of a one side of a room might have walls that are slightly bent or stretched. Simply rotating and translating these deformed submaps to align them doesn't work. "We need to make sure all the submaps are deformed in a consistent way so we can align them well with each other," Carlone explains. A more flexible approach Borrowing ideas from classical computer vision, the researchers developed a more flexible, mathematical technique that can represent all the deformations in these submaps. By applying mathematical transformations to each submap, this more flexible method can align them in a way that addresses the ambiguity. Based on input images, the system outputs a 3D reconstruction of the scene and estimates of the camera locations, which the robot would use to localize itself in the space. "Once Dominic had the intuition to bridge these two worlds -- learning-based approaches and traditional optimization methods -- the implementation was fairly straightforward," Carlone says. "Coming up with something this effective and simple has potential for a lot of applications. Their system performed faster with less reconstruction error than other methods, without requiring special cameras or additional tools to process data. The researchers generated close-to-real-time 3D reconstructions of complex scenes like the inside of the MIT Chapel using only short videos captured on a cell phone. The average error in these 3D reconstructions was less than 5 centimeters. In the future, the researchers want to make their method more reliable for especially complicated scenes and work toward implementing it on real robots in challenging settings. "Knowing about traditional geometry pays off. If you understand deeply what is going on in the model, you can get much better results and make things much more scalable," Carlone says.

Share

Share

Copy Link

MIT researchers have created a new AI-driven system that enables robots to rapidly generate 3D maps of large environments by stitching together smaller submaps, overcoming limitations of existing machine learning models that can only process limited images at a time.

Revolutionary Mapping Technology for Emergency Response

MIT researchers have developed a groundbreaking AI-driven system that enables robots to rapidly create detailed 3D maps of large, complex environments—a breakthrough that could revolutionize search-and-rescue operations and industrial automation

1

. The system addresses a critical limitation in current robotic navigation technology by processing an unlimited number of images to generate accurate environmental maps in seconds.Overcoming Current Limitations in Robot Navigation

The challenge of simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) has long plagued robotics researchers. While recent machine learning models have shown promise in performing this complex task using only onboard camera images, they face a significant bottleneck: even the most advanced models can only process approximately 60 images at a time

2

. This limitation proves catastrophic in real-world scenarios where search-and-rescue robots must quickly traverse large disaster zones, processing thousands of images to complete life-saving missions."For robots to accomplish increasingly complex tasks, they need much more complex map representations of the world around them. But at the same time, we don't want to make it harder to implement these maps in practice," explains Dominic Maggio, an MIT graduate student and lead author of the research

1

.Innovative Submap Stitching Approach

The MIT team's solution combines cutting-edge AI vision models with classical computer vision techniques to create a system that generates smaller submaps of scenes before "gluing" them together into comprehensive 3D reconstructions

2

.

Source: MIT

This incremental approach allows the system to process unlimited images while maintaining real-time position estimation capabilities.

Initially, the seemingly simple solution presented unexpected challenges. Maggio discovered through analysis of 1980s and 1990s computer vision research that machine learning models introduce ambiguities into submaps, making traditional alignment methods ineffective

1

. Unlike conventional methods that rely on simple rotations and translations, the new system accounts for deformations where walls might appear bent or stretched in individual submaps.Addressing Technical Challenges Through Mathematical Innovation

"We need to make sure all the submaps are deformed in a consistent way so we can align them well with each other," explains Luca Carlone, associate professor in MIT's Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and senior author of the research

1

. The team developed a flexible mathematical technique that represents all deformations within submaps, applying transformations that enable proper alignment despite inherent ambiguities.This approach eliminates the need for pre-calibrated cameras or expert system tuning, making the technology more accessible for real-world deployment. The system's simplicity, combined with its speed and reconstruction quality, positions it for scalable applications across multiple industries.

Related Stories

Broad Applications Beyond Emergency Response

While search-and-rescue operations represent the most compelling use case, the technology's applications extend far beyond disaster response. The system could enhance extended reality applications for VR headsets, enable industrial robots to efficiently navigate warehouses for inventory management, and support autonomous vehicles in complex urban environments

2

.Research Team and Future Presentations

The research team includes Maggio, postdoc Hyungtae Lim, and Carlone, who serves as principal investigator in the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems and director of the MIT SPARK Laboratory. Their findings will be presented at the prestigious Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, with research published on the arXiv preprint server

2

.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

AI-Powered Navigation Breakthrough: Robots Learn to Stay on Track Without Maps

28 Aug 2025•Technology

MIT Develops Novel AI Technique for Training General-Purpose Robots

29 Oct 2024•Science and Research

Generative AI Revolutionizes Robot Training: MIT's LucidSim Enhances Real-World Performance

13 Nov 2024•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Meta strikes up to $100 billion AI chips deal with AMD, could acquire 10% stake in chipmaker

Technology

3

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with supply chain risk label over AI safeguards for military use

Policy and Regulation