Nvidia's largest Southeast Asia partner faces probe over alleged chip smuggling to China

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Former Chinese gaming company with China govt ties accused of smuggling banned AI GPUs -- Nvidia's biggest Southeast Asia customer exposes the limits of U.S. AI export controls

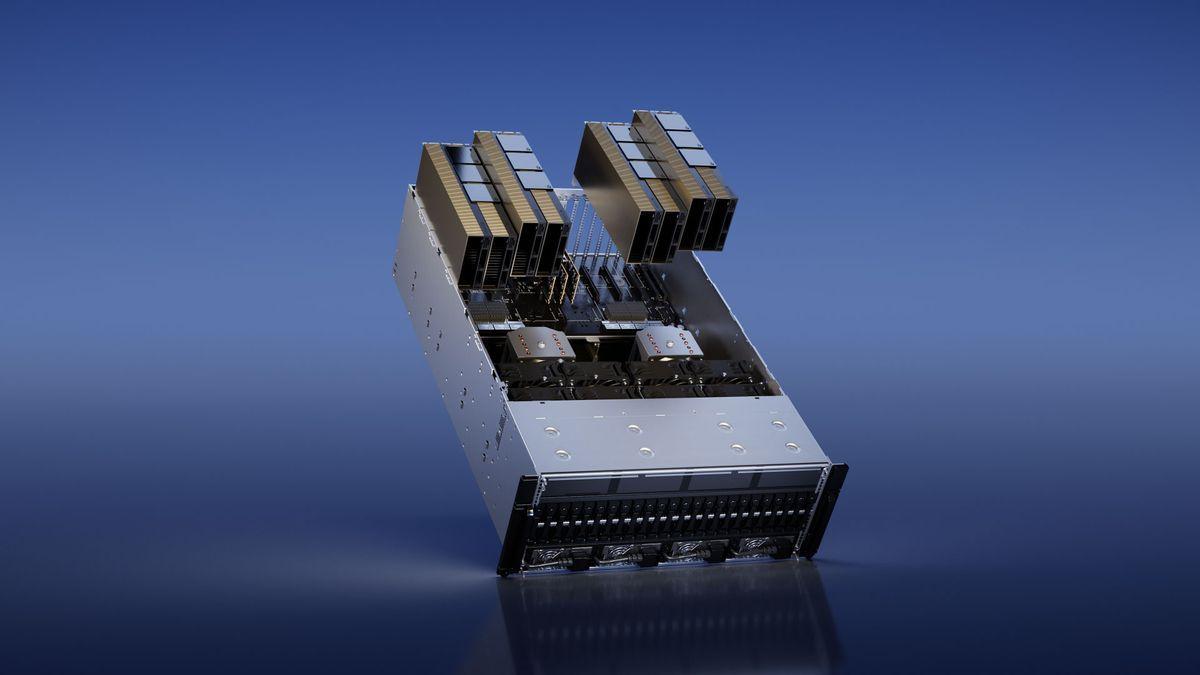

When U.S. lawmakers tightened export controls on advanced AI processors, their goal was straightforward enough: slow China's access to cutting-edge compute hardware by restricting direct sales of the most capable GPUs. Three years later, the policy is colliding with the realities of globalized supply chains, reseller-driven distribution models, and explosive demand for AI accelerators. Nothing has made that collision clearer than the scrutiny that Megapseed International is currently facing. Megaspeed -- formerly 7Road International, a Chinese gaming company with ties to the state -- describes itself as a "premier business partner of Nvidia" that specializes in AI computing resources. The company has rapidly become Nvidia's largest buyer in Southeast Asia, and U.S. officials and Singaporean authorities are examining whether Megaspeed acted as a conduit for restricted Nvidia AI chips ultimately destined for China. According to a special report by Bloomberg, the scale and speed of Megaspeed's purchases, combined with gaps between its declared data center capacity and the volume of hardware imported, have raised questions about whether U.S. export controls are being circumvented through third-party jurisdictions. While Nvidia has said it has found no evidence of chip diversion in the past, this latest episode concerning Megaspeed highlights the broader problem of export controls, which are stringent on paper but increasingly difficult to enforce in practice once hardware passes through layers of intermediaries. Nvidia does not sell most of its data center GPUs directly to end users. Instead, it relies on a sprawling ecosystem of distributors, system integrators, cloud providers, and regional partners. This model scales efficiently in normal markets, but it complicates enforcement when export rules hinge on end use and final destination rather than the point of sale. After the U.S. Commerce Department imposed controls on A100 and H100 GPUs in October 2022, Nvidia responded by creating lower-spec China-only variants such as the A800 and H800. When those too were restricted in late 2023, Nvidia introduced a new lineup of compliant parts, including the H20, L20, and L2. Each iteration was designed to remain below defined interconnect and performance thresholds while preserving software compatibility. This approach allowed Nvidia to continue serving Chinese customers legally on paper; however, in practice, it also created a gray zone in which large volumes of AI hardware could be moved through third countries before regulators had clear visibility into where systems were deployed or how they were ultimately used. Once GPUs are installed in servers and shipped as complete systems, tracing individual accelerators becomes significantly harder. Megaspeed managed to slot itself nicely within this gray zone. The company, which traces its roots to a Chinese gaming business that was subsequently spun out and rebranded in Singapore, reportedly committed to purchasing billions of dollars' worth of Nvidia hardware over a short period. That drew attention, particularly when U.S. officials noticed discrepancies between the volume of chips imported and the capacity of Megaspeed's disclosed data center footprint. Singapore's government has confirmed it is investigating potential export control violations, while U.S. agencies are examining whether restricted hardware was indirectly diverted to China. Unfortunately, the Megapseed situation is not an isolated incident. Over the past year, U.S. authorities have uncovered multiple schemes involving the illicit export of Nvidia GPUs to China, including instances in which companies misdeclared shipments, used shell entities, or physically removed accelerators from servers after inspection. In late 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice shut down a major China-linked smuggling network that allegedly routed tens of millions of dollars' worth of H100 and H200 GPUs to China by falsifying documentation and relabeling hardware. In a similar case, DeepSeek was accused of establishing "ghost" data centers in Southeast Asia to pass audits, then shipping GPUs onward. These cases all highlight the difficulty of enforcing controls once hardware leaves Nvidia's hands. Export rules are primarily enforced at the point of sale and shipment and rely heavily on declarations of end use and on downstream compliance by resellers and customers. When demand is strong enough, the incentives to circumvent those declarations multiply -- and China's appetite for AI compute remains enormous. Domestic alternatives, including Huawei's Ascend accelerators, have improved but still lag Nvidia in software maturity and ecosystem support. Even Chinese firms that publicly promote local silicon often rely on Nvidia hardware for training large models or running advanced inference workloads. That persistent demand has created a shadow market willing to pay significant premiums for restricted GPUs. From Washington's perspective, export controls are intended to impose real friction on China's AI development by constraining access to the highest-end compute. The logic is that advanced model training scales with available GPU throughput, memory bandwidth, and interconnect performance. Denying that hardware should slow progress in both commercial and military AI applications. The problem is that for China, which is so far behind the West in real terms, partial access is still extremely meaningful. Even a modest influx of smuggled or otherwise indirectly routed GPUs can support the likes of research projects and inference deployments. While it's estimated that illicit imports account for only a fraction of China's total compute capacity, even marginal gains can make a big difference at the frontier of model development. At the same time, aggressive controls carry trade-offs. They push Chinese companies to accelerate domestic chip development, fragment global supply chains, and incentivize exactly the kinds of gray-market behavior now under investigation. They also place companies like Nvidia in a difficult position, caught between compliance obligations and the commercial reality that much of their addressable market lies outside the U.S. and its closest allies. In early 2025, the Commerce Department expanded controls to cover not just hardware but also certain AI model weights, while creating new licensing frameworks for trusted partners and data center operators. While some of these controls have been relaxed by President Trump, with H200 sales now permitted to vetted Chinese customers subject to a 25% import duty, the back-and-forth indicates clear uncertainty among decision-makers about what level of restriction, if any, will achieve the desired outcome. Indeed, it's difficult to argue that allowing the H200, some of the most advanced silicon made by Nvidia, does anything to serve the U.S. goal of hindering China. Whether or not investigators ultimately find evidence that Megaspeed violated export laws, there's a structural weakness in the current system. Export controls assume that intermediaries can be trusted to enforce end-use restrictions at scale, across borders, and over time. As long as global demand for Nvidia-class AI compute outpaces legal supply to China, however, pressure will build on the seams of the system.

[2]

Nvidia's Biggest Southeast Asian Partner Dogged by China Chip Smuggling Questions

In an industry run by titans, a Singapore AI firm called Megaspeed International Pte. is drawing an unusual amount of attention. In less than three years, the once-obscure spinoff of a Chinese gaming enterprise has evolved into the single largest Southeast Asian buyer of Nvidia Corp. chips -- a rapid ascent that's lifted hopes for a regional champion in the lucrative business of AI cloud computing. Now Megaspeed finds itself a focal point of Washington's long-held fears about semiconductor smuggling into China, an issue of escalating concern among national security hawks despite Nvidia's repeated assurances that chip diversion doesn't exist. The US government is investigating both Megaspeed's ownership structure and whether it's smuggled Nvidia chips to the Asian country, which would be a major breach of curbs imposed to limit China's AI and military prowess, according to people familiar with the effort, who asked for anonymity because the details are private. Singapore is looking into whether Megaspeed has violated local laws, the country's police force confirmed, without specifying which ones. A government spokesperson in Malaysia, which hosts the lion's share of Megaspeed's operations, said when asked about the company that they "cannot comment on specific firms beyond confirming that compliance monitoring is ongoing." The spokesperson didn't respond to follow-up questions about the scope and nature of Malaysia's efforts. At stake is more than Megaspeed's individual fate. The US probe could shape how American policymakers view a business model that brings Nvidia billions of dollars in revenue and underpins a data center boom in Southeast Asia. Megaspeed denies any wrongdoing and says it abides by all regulations from the US and elsewhere relevant to its operations. "Megaspeed is a Singapore-based company, operating fully in compliance with all applicable laws, including US export control regulations," the firm said in an emailed statement. It declined to comment further, instead directing Bloomberg to its website and to Nvidia. An Nvidia spokesperson said its inquiry into Megaspeed found no evidence of diversion and showed that the company is fully owned and operated outside of China, with no China shareholders. Megaspeed is offering "a cloud service permitted under the export control rules," the spokesperson said. Megaspeed is what's called a neocloud, meaning it specializes in providing access to high-performance computing equipment used for AI workloads. At multiple facilities in Southeast Asia, the company rents Nvidia chips to Chinese tech giant Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., itself a recent subject of US national security concerns, according to documents reviewed by Bloomberg and people familiar with the matter, who asked for anonymity to discuss confidential business matters. Washington generally allows that setup, which Nvidia says helps secure American AI leadership, but there have long been calls to close what some see as a loophole. If it turns out that any of Megaspeed's Nvidia chips have physically made their way to China absent a US license -- or that the company isn't strictly Singaporean, but rather Chinese -- that could shape Washington's conversations around export controls for China and beyond. Those curbs are the preeminent policy concern of the world's most valuable company, not to mention the Chinese firms that rely on its processors in a full-throttle AI race. And the debate is a live one: Just this month, President Donald Trump said he'd greenlight sales to China of certain advanced Nvidia graphics processing units, or GPUs, that Washington had effectively banned from export to the Asian country. Nvidia, which conducts regular spot-checks of data centers around the world, told Bloomberg that it went to Megaspeed's facilities multiple times to verify that there's nothing untoward. "Our visits confirmed that the GPUs shipped to Megaspeed by our partners are where they are supposed to be," an Nvidia spokesperson said in mid-November. Bloomberg didn't find evidence that any of Megaspeed's Nvidia chips have been diverted to China, or that the company has otherwise violated US export controls or other laws. Still, a review of hundreds of pages of trade records, corporate filings, job postings and private documents from Megaspeed and its partners -- plus interviews with dozens of people across six countries, including US and foreign government and industry officials, as well as technical experts such as SemiAnalysis -- revealed inconsistencies in Megaspeed's Southeast Asia chip inventory and overall data center footprint. All of the people interviewed requested anonymity to be able to discuss sensitive information. The Nvidia spokesperson, asked in mid-December about those specific discrepancies, said that Nvidia has identified "substantially" all the products its partners sent to Megaspeed, and will visit again in the near future. Since its founding in 2023 through November of this year, Megaspeed has imported Nvidia hardware worth at least $4.6 billion, containing at least 136,000 Nvidia graphics processing units, or GPUs, according to Bloomberg analysis of Malaysian and Indonesian customs records. Those records were compiled by the platform Big Trade Data Ltd., a Beijing-based provider of export and import data that was established in 2004. More than half of Megaspeed's chips are from Nvidia's current-generation Blackwell lineup -- processors that Trump, even after allowing Nvidia to ship its best previous-generation product to China, said he won't approve for export to the Asian country. Megaspeed got the majority of its Blackwell processors more than half a year ago and another batch last month. Yet when Nvidia officials recently visited Megaspeed's data centers, they only saw hardware that contains a few thousand Blackwell GPUs, according to inventory information the chipmaker shared with the US government, described by people familiar with the Megaspeed probe. Asked about the rest of the Blackwell chips, an Nvidia official said the company visited separate Megaspeed warehouses, where it saw the hardware imported earlier and confirmed it hadn't been diverted to China. But this person declined to specify whether the number of components Nvidia cataloged in storage matches the outstanding volume from Bloomberg's analysis of Malaysian customs records. Megaspeed didn't answer multiple queries on the location of and plans for those processors, nor on its facilities writ large. On its website, Megaspeed describes three data centers, previously identified as being in Malaysia and Indonesia and now all listed as "East South Asia." But the company told potential investors that in addition to projects in those two countries, it was building an Nvidia computing cluster in a "specific area" of a third, unnamed nation, according to a slide deck Megaspeed circulated in 2024. In the presentation, obtained by Bloomberg, Megaspeed's "specific area" facility was the only one not identified as being in Southeast Asia. To depict the project, Megaspeed used a rendering of a massive AI data center in Shanghai, which corporate records show was financed in part by Megaspeed's original Chinese parent, plus a holding company created by Megaspeed's founder. Megaspeed also has something of a Chinese corporate twin. This firm used similar presentation materials to Megaspeed's, had a nearly identical website to a Megaspeed sub-brand and claimed Megaspeed's Southeast Asia employees as its own. It's also posted job ads at and near the Shanghai data center whose rendering was used in Megaspeed's investor deck -- including for engineering work on restricted Nvidia GPUs. That's all likely to raise further questions in Washington. Still, what matters most for Nvidia's business with Megaspeed is whether the US investigation, first reported by the New York Times in October, uncovers concrete violations of chip curbs. Those rules require a license from Washington for advanced AI chip exports to China itself, as well as a license for shipments outside China that are for entities headquartered in the Asian country or with an "ultimate parent" headquartered there. The regulations don't define "ultimate parent." The US Commerce Department's Bureau of Industry and Security, in charge of Washington's investigation, declined to comment, and people familiar with the effort didn't provide a time frame for the probe, which could ultimately end without any penalty or resolution. The US hasn't put Megaspeed on any trade restriction lists, nor asked Nvidia to cease doing business with the company, a spokesperson for the chipmaker said. Malaysia's Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry, asked about Megaspeed, said that "currently, there is no clear evidence to suggest" export control violations in its jurisdiction. A spokesperson added that the agency welcomes "any additional credible information that is brought to our attention to assist our investigation." Singapore's police force several months ago detained the woman who set up Megaspeed, Huang Le, people familiar with the matter said, meaning that she was brought in for questioning -- and, one person added, restricted from leaving Singapore. Huang Le is not currently in custody and is assisting the police with their Megaspeed investigation, according to one of the people. The police declined to comment on their questioning of Huang Le or elaborate on their overall probe into Megaspeed. The company declined to comment on Huang Le's detention, and Bloomberg was unable to reach Huang Le directly, including after several visits to her registered Hong Kong address in an attempt to secure her contact information from people present there. Megaspeed's beginnings in March 2023 are best understood by starting in October 2022. That month, President Joe Biden imposed sweeping restrictions on shipments to China of advanced AI chips and the tools to make them. The move, justified on a national security basis, created supply constraints for the Asian country's AI developers and impeded Chinese chipmakers' ability to manufacture their own processors. While companies like Huawei Technologies Co. have shown progress in competing with Nvidia -- and Beijing wants AI developers like Alibaba to use homegrown semiconductors -- firms in the Asian country still broadly covet Nvidia chips, which are the industrial standard for training and running large language models. There are effectively two ways for Chinese companies to get access to those processors: renting hardware that's physically in another country, which Washington generally allows, or bringing it into China, which is illegal without a US license. Megaspeed is a rental business. The company was spun off from one of China's largest video game enterprises, 7Road Holdings Ltd., five months after the US unveiled its 2022 rules. 7Road first sold its Singapore subsidiary to a British Virgin Islands entity called Huang Le Ltd., and Huang Le -- the woman detained a few months ago in Singapore and currently assisting the police investigation -- assumed control. In November 2023, Huang Le Ltd. sold Megaspeed to a Singapore shell company owned by its current CEO, a Singapore national named Tan Yong Pong. Four days later, Megaspeed was designated an official Nvidia Cloud Partner. At the end of that year, it had $5.7 million on hand. Since then, trade records show that Megaspeed has imported goods worth more than a thousand times its cash balance in 2023, the most recent year for which the company's financial information is available. Megaspeed didn't answer questions about its funding sources. At least two-thirds of Megaspeed's imports by value are Nvidia processors, though the actual number may be greater. Bloomberg only counted shipments with specific Nvidia product names or serial numbers in the description field, while excluding thousands of unlabeled AI servers in the price range of Nvidia hardware and with similar serial numbers, as well as products called Nvidia GPUs but lacking further identifying information. Megaspeed completed the bulk of its Nvidia chip purchases in the six weeks leading up to May 15, 2025, trade records show. That's when the US was set to require permits for AI chip exports to Southeast Asia as part of a Biden-era global framework that Trump scrapped before it took effect. Many of Megaspeed's chips are used by Alibaba, which declined to comment for this story. The US generally allows Chinese firms to rent advanced Nvidia processors located outside the Asian country, although there are exceptions for certain military use cases. BIS declined to comment on how officials would evaluate Megaspeed's relationship with Alibaba, which along with Beijing has denied recent US allegations that it supplies China's People's Liberation Army. Nvidia said it hasn't "seen any suggestion that any foreign military is attempting to use these products, which are most often deployed for commercial uses such as consumer recommender systems and chatbots." The chipmaker also says that AI chip rental is, by design, core to the US strategy: "Export controls forfeited the world's second-largest commercial market to foreign competitors, and America cannot afford to lose all of Asia next." Smuggling is a nagging concern. In the three years since Washington restricted Nvidia exports, a black market has emerged to get those components physically into China. Nvidia Chief Executive Officer Jensen Huang said in May that there's "no evidence" of AI chip diversion, but senior US officials have publicly and privately contradicted him, albeit without detailing the suspected scale of the problem. "It's happening," Jeffrey Kessler, who runs BIS, told lawmakers just weeks after Huang's remarks. "It's a fact." Singapore, beyond its Megaspeed investigation, has arrested executives of another official Nvidia partner for allegedly defrauding suppliers about the ultimate destination of AI servers first sent to Malaysia, a case on which Nvidia has declined to comment. A Singapore trade ministry spokesperson said the island nation doesn't "condone businesses deliberately using their association with Singapore to circumvent or violate the export controls of other countries." Malaysia earlier this year imposed its own permit requirements on exports of advanced American AI chips, and recently agreed to align with all of Washington's curbs and ensure its companies don't "backfill or undermine" them -- part of a US trade accord that's drawn China's rebuke. Kuala Lumpur is committed to guaranteeing that "advanced technologies hosted in Malaysia are used responsibly," a government representative said. (Officials in Thailand, where Megaspeed also operates, declined to comment, while those in Indonesia didn't respond to questions.) US authorities, meanwhile, have unveiled details of three alleged chip smuggling schemes since August, including one disclosed this month in which an alleged participant has already pled guilty. Nvidia has said the cases show that "smuggling is a nonstarter" and that there's "strict scrutiny and review" even for sales on the secondary market. "Over the years, people have speculated about diversion," Jensen Huang told Bloomberg TV in November. "We've chased down every single concern, and we have repeatedly tested and sampled data centers around the world and found no diversion." In Megaspeed's case, Nvidia told US officials it visited data centers run by eight operators -- one in Indonesia, one in Thailand, and the rest in Malaysia, said the people familiar with the matter. Megaspeed, like other neoclouds, rents space at those facilities and installs its own chips. Across the sites, Nvidia cataloged Megaspeed-owned servers and racks equivalent to some 86,000 GPUs. Five operators didn't respond to multiple queries seeking to confirm that inventory, while one said it can't disclose customer details. Equinix Inc., which Nvidia told Washington had a small number of Megaspeed's B200 servers in Malaysia, told Bloomberg that neither of its two facilities in the country had any of those products. Kuala Lumpur-based AIMS Data Centre, where Nvidia observed around a hundred of Megaspeed's H200 and B200 servers, said via email that that information is "incorrect. Megaspeed is not our customer." Asked about Equinix and AIMS' statements, an Nvidia spokesperson said the chipmaker has "identified substantially all the products that our customers shipped to Megaspeed." They added that Nvidia is developing an optional software service for data center operators to monitor their GPU inventory, and also plans to "visit Megaspeed's facilities again in the near future, as we continue to perform spot checks on customers in the region." BIS didn't answer questions from Bloomberg on how the agency interprets such visits. Two senior US officials have said publicly that it's easy to detect smuggling by counting the server racks or chips in a data center. Others said in interviews that they worry installed Nvidia servers could be disassembled, and the individual GPUs smuggled to China, without anything immediately looking amiss. Asked whether they'd seen evidence of that happening, these officials cited media reports and conversations with industry officials. Nvidia says this tactic would be a "dismal failure, technically and economically," if attempted. Data centers aren't the only Megaspeed facilities Nvidia visited. The vast majority of Megaspeed's $2.4 billion worth of Bianca boards, the circuit boards that house Nvidia's top-end GB200 and GB300 semiconductors, were unaccounted for at the sites Nvidia described to Washington. After Bloomberg asked about those products, the chipmaker went to separate Megaspeed warehouses, an Nvidia official said, and confirmed the Bianca boards are there. This person declined to specify the number observed in storage, nor where and when the chips -- imported more than half a year ago -- would be put to use. "Building data centers is a complex process that takes many months and involves many suppliers, contractors and approvals," an Nvidia spokesperson said. That's not the only discrepancy. The data center footprint Nvidia described to Washington differs from Megaspeed's own public account of its facilities -- and how Megaspeed has privately described its operations. The biggest question is the location of the "specific area" project touted in the investor presentation Megaspeed circulated in 2024. The slide deck, translated from its original Mandarin, said simply: "As of now, the largest NCP (Nvidia Cloud Partner) computing power cluster has been built in a specific area." Megaspeed declined to provide further details, but its investor presentation gave some indications of where the site could be. The data center is the only one not on a slide about Southeast Asia facilities. The deck also said it was being constructed in a third country, beyond the Malaysia and Indonesia presence described both in that document and on an old version of Megaspeed's website. (At the time the presentation was circulated, Megaspeed hadn't yet expanded to Thailand.) Megaspeed's slide deck also contains a map, which depicts the "specific area" project with a computer-generated image. The same rendering appears in reports about two AI infrastructure projects in China. One of those projects, upon closer inspection, has a substantially different physical layout from the image in Megaspeed's presentation. The other, a Shanghai data center that state media has said will be China's largest, is a match. It's called the Yangtze River Delta Project, and it counts Tencent Holdings Ltd., China's most valuable company, as a tenant. ("Our data center operations fully comply with all applicable laws and regulations," a Tencent spokesperson said.) 7Road, Megaspeed's original parent, invested in the site for a few months in 2020, according to a report from another company that helped finance the project. A much longer-term backer is a private equity firm called Shanghai Hexi Investment Co., which said in a 2020 WeChat post that its investing arm launched a financing vehicle to support the site alongside the local government. The following year, in 2021, a local media report called the top executive of Shanghai Hexi the "president" of the Yangtze River Delta Project. News footage from March 2025 shows he attended a progress meeting with senior corporate and government officials at the data center campus. Shanghai Hexi was also, until this past August, 48% owned by a holding company founded by Megaspeed's Huang Le. To be sure, that doesn't mean Megaspeed and Shanghai Hexi ever had a direct relationship. Huang Le was listed as one of Shanghai Hexi's directors in an official company WeChat post in 2016, but it wasn't until years later that she created Megaspeed. Earlier this year, a LinkedIn profile of Megaspeed's Singapore-based "Regional Financial Controller" listed a concurrent position as the "Post-Investment Manager Megaspeed SG" for "Hexi Fund" in Shanghai. (Shanghai Hexi goes by Hexi Fund on its official WeChat account.) But Bloomberg couldn't independently establish whether this profile, which recently lost references to Megaspeed, in fact was legitimate for someone who worked either there or at Shanghai Hexi. The LinkedIn user and private equity firm didn't respond to requests for comment, while Megaspeed didn't answer questions about the user's employment status. In any case, the Megaspeed employee preoccupying Washington officials is Huang Le herself. While Megaspeed's official registries list a Singapore national as its CEO, a LinkedIn profile with the name Huang Xiaole claims that title. (Xiao is usually used as a term of endearment in Mandarin.) In photos of a 2024 Taipei tech conference event attended by Nvidia's Jensen Huang, a woman named Alice Wong -- who the New York Times reported is the same person as Huang Le -- was identified in a separate company's LinkedIn caption as Megaspeed's chairwoman. (Wong is the Cantonese pronunciation and romanization of the Chinese surname Huang.) Bloomberg reached out several times to Huang Xiaole to confirm her identity, and she didn't respond. Megaspeed declined to comment on whether Huang Le maintains any official or unofficial role. Shanghai Hexi and the holding company she founded, where corporate filings show she relinquished her personal shares in 2017, didn't respond to multiple requests. What is clear is that the holding company Huang Le founded, which under her stewardship took a stake in Shanghai Hexi, has multiple additional connections to the Yangtze River Delta Project whose rendering is in Megaspeed's slide deck. In 2024, one of the holding company's subsidiaries secured and installed "computing servers" there, according to documents that didn't specify the hardware in question. Another subsidiary, Shanghai Shuoyao Technology Co., solicited applicants to work at the Yangtze River Delta Project before transferring to Malaysia's southern state of Johor. Shanghai Shuoyao looks like Megaspeed in several ways. The company describes itself in job postings as a leading AI infrastructure provider in China and abroad. But photos of its Indonesia staff, posted on Shanghai Shuoyao's official WeChat account, actually depict Megaspeed's employees there, according to a person with knowledge of the matter, who asked not to be identified because they aren't authorized to speak publicly. Shanghai Shuoyao's map of its data centers, also shared publicly on the company's WeChat, resembles what Megaspeed privately showed potential investors -- with one main difference being that Shanghai Shuoyao references facilities in China. Shanghai Shuoyao's website, meanwhile, was almost a carbon copy of Megaspeed's page for its sub-brand Lumina, down to Megaspeed's name appearing in Shanghai Shuoyao's source code. The primary distinction between the two, other than language, was which Nvidia products they displayed. (As of the time of publication, Lumina's website appears to be down, while Shanghai Shuoyao's no longer references Nvidia. Shanghai Shuoyao didn't respond to multiple requests for comment.) At the time Bloomberg viewed both websites in September, Megaspeed's version touted Nvidia's more advanced chips -- specifically the B200, H100 and H200, hardware Washington had effectively banned from sale to China from the moment those products went to market. Shanghai Shuoyao, on the other hand, only displayed processors that have been permitted, at least in the past, to be shipped to the Asian country. Yet on the Chinese hiring website Liepin, Shanghai Shuoyao indicated that it has, or at least anticipates getting, restricted Nvidia chips. The company posted an engineering job ad, which Bloomberg viewed in September and is no longer there, for work on "H100, H200 and other GPU models." The address for that role is at a business park in Shanghai, around half a kilometer from the Yangtze River Delta Project. Nvidia -- which functions as a sort of kingmaker in an industry paramount to the US-China competition -- didn't answer questions about Shanghai Shuoyao, the Yangtze River Delta Project and the other companies involved there. BIS declined to comment on whether it's come across the same network of Chinese firms in its own Megaspeed probe. For Megaspeed, the most pressing concern is how the US investigation into possible export control violations is resolved. But the company could also be affected by Washington's active debate about the very chip curbs BIS is trying to enforce. Trump's decision to allow additional Nvidia AI chip shipments to China, a policy reversal lawmakers are trying to prevent, could affect Chinese firms' demand for AI chip rental in Southeast Asia -- particularly if the US approves, and Beijing accepts, high volumes of direct sales. Trump's team is also trying to set rules for semiconductor exports to every other country, including those where Megaspeed operates. Trump in May nixed Biden's answer to that global question, which would've given the US government a say over advanced processor sales worldwide, and also prevented Chinese firms from training frontier AI models on restricted hardware located outside the Asian country. At the time, Trump's team hinted at continued restrictions. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said in June that Washington would allow allies to buy AI chips provided they go to a US-run data center, "and the cloud that touches that data center is an approved American operator -- so we control it while it's over there." Washington exerts such control by writing conditions into export licenses. BIS by July had drafted a rule to require such permits for Malaysia and Thailand in particular, specifically to address smuggling concerns, as the Trump administration works toward a promised broader framework. As the year comes to a close, that rule hasn't been implemented, and there isn't a clear overarching plan. That's left government and industry officials in the US and overseas unsure how Trump ultimately wants to treat companies like Megaspeed, a Singaporean cloud provider that works with local Southeast Asian data center operators and rents Nvidia chips to a Chinese tech champion. For now, though, Megaspeed is free to buy as many processors as it likes. Last month, trade records show it imported at least 17,544 of Nvidia's GB300s, the most advanced and sought after GPUs on the market, worth some $787 million.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Megaspeed International, formerly a Chinese gaming company, has become Nvidia's biggest Southeast Asian customer in under three years. Now the Singapore-based firm faces US government investigation over potential chip smuggling to China, exposing critical gaps in export controls designed to limit China's AI capabilities. The case highlights how complex global AI supply chains make enforcement increasingly difficult.

US Government Investigation Targets Nvidia's Largest Southeast Asian Customer

Megaspeed International, a Singapore-based firm that emerged as Nvidia's largest buyer in Southeast Asia, now sits at the center of a US government investigation examining whether the company smuggled restricted AI chips to China

2

. The probe focuses on Megaspeed's ownership structure and potential violations of U.S. AI export controls designed to limit China's AI capabilities, according to people familiar with the investigation2

. Singapore authorities have confirmed they are investigating potential export control violations, while Malaysian officials acknowledged that compliance monitoring is ongoing for operations within their borders2

.

Source: Bloomberg

The scrutiny comes after U.S. officials noticed significant discrepancies between the volume of chips Megaspeed imported and its disclosed data center footprint

1

. The company, formerly known as 7Road International, a Chinese gaming enterprise with state ties, rapidly transformed into a major player in AI computing resources after its 2023 founding1

. Megaspeed committed to purchasing billions of dollars' worth of Nvidia hardware over a remarkably short period, drawing attention from both U.S. and Singaporean regulators1

.Export Controls Face Enforcement Challenges in Global AI Supply Chain

When the U.S. Commerce Department imposed export controls on advanced AI processors like the A100 and H100 GPUs in October 2022, the goal was clear: slow China's access to cutting-edge compute hardware

1

. Three years later, the policy collides with the realities of globalized supply chains and reseller-driven distribution models1

. Nvidia doesn't sell most data center GPUs directly to end users, instead relying on distributors, system integrators, cloud providers, and regional partners1

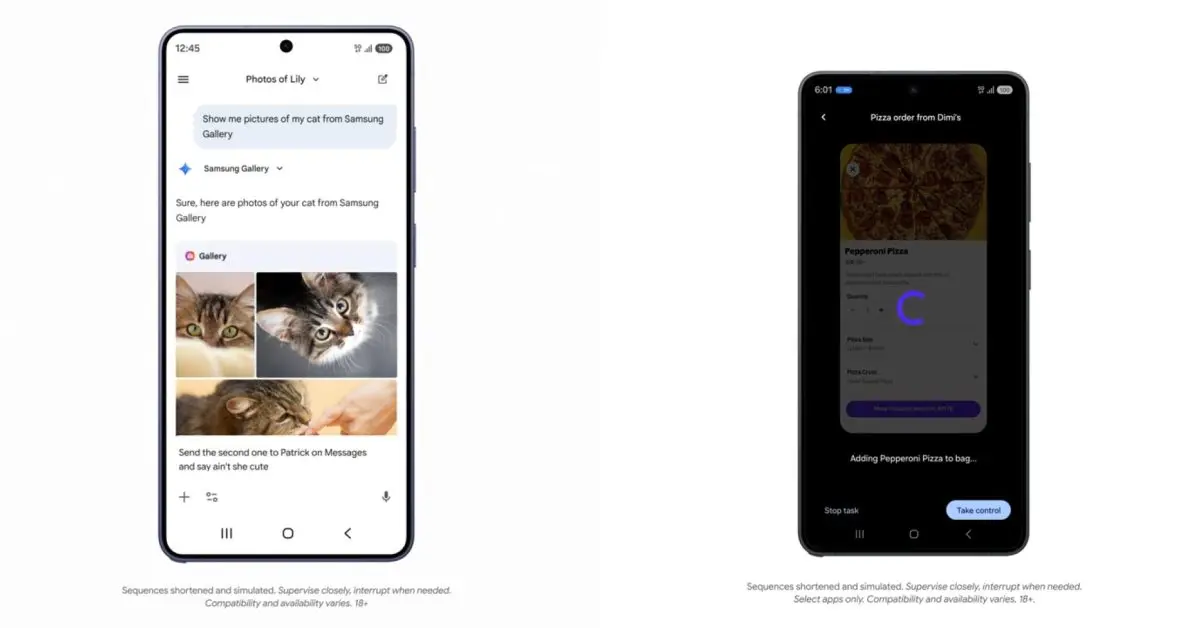

. This approach scales efficiently but complicates enforcement when export rules depend on end use and final destination rather than point of sale.Megaspeed operates as a neocloud provider, specializing in high-performance computing equipment for AI workloads at multiple facilities across Southeast Asia

2

. The company rents Nvidia chips to Chinese tech giant Alibaba, a setup Washington generally allows but that some critics view as a loophole2

. Once AI accelerators are installed in servers and shipped as complete systems, tracing individual processors becomes significantly harder1

.Pattern of Illicit GPU Exports to China Emerges

The Megaspeed case isn't isolated. Over the past year, U.S. authorities uncovered multiple schemes involving smuggling restricted Nvidia AI chips to China

1

. In late 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice shut down a major China-linked smuggling network that allegedly routed tens of millions of dollars' worth of H100 GPUs and H200 processors to China by falsifying documentation and relabeling hardware1

. DeepSeek was accused of establishing "ghost" data centers in Southeast Asia to pass audits before shipping GPUs onward1

.These cases expose the difficulty of enforcing controls once hardware leaves Nvidia's hands. Export rules are primarily enforced at the point of sale and shipment, relying heavily on declarations of end use and downstream compliance by resellers

1

. China's persistent demand for compute capacity has created a gray market willing to pay significant premiums for restricted GPUs, as domestic alternatives like Huawei's Ascend accelerators still lag Nvidia in software maturity and ecosystem support1

.Related Stories

Nvidia Defends Partner Amid Scrutiny

Nvidia maintains it found no evidence of chip diversion after conducting multiple spot-checks at Megaspeed's facilities. "Our visits confirmed that the GPUs shipped to Megaspeed by our partners are where they are supposed to be," an Nvidia spokesperson stated

2

. The company's inquiry concluded that Megaspeed is fully owned and operated outside China, with no China shareholders, and that it offers "a cloud service permitted under the export control rules"2

.Megaspeed denies any wrongdoing, stating it operates "fully in compliance with all applicable laws, including US export control regulations"

2

. Bloomberg's review didn't find evidence that Megaspeed's Nvidia chips were diverted to China, though inconsistencies in the company's chip inventory and data center footprint raised questions2

. The outcome of this probe could reshape how American policymakers view the neocloud business model that brings Nvidia billions in revenue and underpins a data center boom across Southeast Asia2

.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Nvidia Supplier Megaspeed Under Investigation for Alleged AI Chip Diversion to China

09 Oct 2025•Technology

US Investigates Potential Circumvention of AI Chip Export Controls via Singapore

31 Jan 2025•Policy and Regulation

Chinese AI Startup Accesses 2,300 Banned Nvidia Blackwell GPUs Through Indonesian Cloud Loophole

14 Nov 2025•Policy and Regulation

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with Defense Production Act over AI military use restrictions

Policy and Regulation

2

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

3

Anthropic accuses Chinese AI labs of stealing Claude through 24,000 fake accounts

Policy and Regulation