U.S. Copyright Office Report Challenges AI Companies' Fair Use Claims for Training Data

5 Sources

5 Sources

[1]

Copyright Office Punts on AI and Fair Use, One of the Biggest Questions Surrounding Gen AI

Katelyn is a writer with CNET covering social media, AI and online services. She graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a degree in media and journalism. You can often find her with a novel and an iced coffee during her time off. If you've been hoping for clarity from the US Copyright Office on AI training -- whether AI companies can use copyrighted materials under fair use or creators can claim infringement -- prepare to be disappointed. The Office released its third report on Friday, and it's not the major win tech companies hoped for, nor the full block some creators sought. The US Copyright Office set out in 2023 to release a series of reports, guidance for creators, dealing with the myriad of legal and ethical issues that arise from AI-generated content from software such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Meta AI and Dall-E. In previous reports, the Copyright Office ruled that entirely AI-generated content can't be copyrighted, while AI-edited content could still be eligible. These reports aren't law, but they give us a picture of how the agency is handling copyright protections in the age of AI. The third report, available now, isn't the final report; it's a "prepublication" version. Still, there won't be any major changes in the Copyright Office's analysis and conclusions in the final report, according to its website, so it does give us a good understanding of the guidance it will offer for future claims. The 108-page report deals primarily with copyright concerns around the training of AI models -- specifically, whether AI companies have legal footing to ask for a fair-use exception, which would let them use copyrighted content without licensing or compensating the copyright holders. In short, the Copyright Office didn't rule out the possibility of a fair-use case for companies using copyrighted material for AI training. But there are a couple of important things that would be a metaphorical strike against a fair-use case, which the report spells out in detail. So it's also possible that an AI company found to be using copyrighted material without the author's permission could be grounds for a copyright infringement claim. It depends on the AI model, how it's used and what it produces. "On one end of the spectrum, uses for purposes of noncommercial research or analysis that do not enable portions of the works to be reproduced in the outputs are likely to be fair," the report says. "On the other end, the copying of expressive works from pirate sources in order to generate unrestricted content that competes in the marketplace ... is unlikely to qualify as fair use. Many uses, however, will fall somewhere in between." The Copyright Office, which is part of the Library of Congress, is the subject of current political controversy. CBS News reports that the department's head, Shira Perlmutter, known as the Register of Copyrights, was fired by President Donald Trump this past weekend. This was a few days after Trump fired the Librarian of Congress, Carla Hayden, on Thursday. Hayden was the first woman and first African American to hold the position. Here's what the Copyright Office wrote on fair use and what you need to know about why the legal web of AI and copyright continues to grow. Tech companies have been pushing hard for a fair-use exception. If they're granted such an exception, it won't matter if they have and use copyrighted work in their training datasets. The question of potential copyright infringement is at the center of more than 30 lawsuits, including notable ones like The New York Times v. OpenAI and Ortiz v. Stability AI. (Disclosure: Ziff Davis, CNET's parent company, in April filed a lawsuit against OpenAI, alleging it infringed Ziff Davis copyrights in training and operating its AI systems.) The Copyright Office said in its report that these cases should still continue in the judicial system: "It is for the courts to weigh the statutory factors together," since there's "no mechanical computation or easy formula" to decide fair use. Writers, actors and other creators have pushed back equally hard against fair use. In an open letter signed by more than 400 of Hollywood's biggest celebrities, the creators ask the administration's office of science and technology policy not to allow fair use. They wrote: "[America's] success stems directly from our fundamental respect for IP and copyright that rewards creative risk-taking by talented and hardworking Americans from every state and territory." For now, it seems we have only a few more answers than before. The big questions around whether specific companies like OpenAI have violated copyright law will have to wait to be adjudicated in court. Fair use is part of the 1976 Copyright Act. The provision grants people who are not the original authors the right to use copyrighted works in specific cases, like for education, reporting and parody. There are four main factors to consider in a fair-use case: one, the purpose of the use; two, the nature of the work; three, the amount and substantiality used; and four, the effect it has on the market. The Copyright Office's report analyzes all four factors in the context of AI training. One important aspect is the transformativeness of the work, which is whether AI chatbots and image generators are creating outputs that are substantially different from the original training content. The report seems to indicate that AI chatbots used for deep research are sufficiently transformative. But image generators that produce outputs in too similar a style or aesthetic to existing work might not be. The report says guardrails that prevent the replication of protected works -- like image generators refusing to create popular logos -- would be evidence that AI companies are trying to avoid infringement. This is despite the fact that the office cites research that proves those guardrails aren't always effective, as OpenAI's Studio Ghibli image trend clearly demonstrated. The report argues that AI-generated content clearly affects the market, the fourth factor. It mentions the possibility of loss of sales, diluting markets through oversaturation and loss of licensing opportunities for existing data markets. However, it also mentions the potential for public benefit from the development of AI products. Licensing, a popular alternative to suing among publishers and owners of content catalogs, is also highlighted as one possible pathway to avoid copyright concerns. Many publishers, including the Financial Times and Axel Springer brands, have struck multimillion-dollar deals with AI companies, giving AI developers access to their high-quality, human-generated content. There are some concerns that if licensing becomes the sole way to attain this data, it will prioritize the big tech companies that can afford to pay for that data, boxing out smaller developers. The Copyright Office writes that those concerns shouldn't have an effect on fair-use analyses and are best dealt with by antitrust laws and the agencies that enforce them, like the Federal Trade Commission.

[2]

U.S. Copyright Office's AI report sparks new fight

Why it matters: The rules for intellectual property in the AI age are going to be set over the next couple of years, but thoughtfulness and nuance face an uphill climb in this era of hyper-partisanship and "move fast, break things" tech firm tactics. The big picture: The use of copyrighted material to train AI models has been controversial since the dawn of ChatGPT, with some publishers and content creators striking deals, some suing and others waiting to see how things shake out. Driving the news: The Copyright Office's "pre-publication" version of its 108-page report argues for a balanced approach that recognizes the contributions of both tech firms and content creators. The report concludes that while some generative AI probably does constitute a "transformative" use, the mass scraping of all data for commercial use probably does not qualify as fair use. The report encourages the U.S. government to help foster the nascent market for licensed content for AI training. Yes, but: The Trump Administration, without directly commenting on the report, almost immediately fired Shira Perlmutter, the head of the Copyright Office. Zoom in: Democrats argue Perlmutter's removal is illegal. Between the lines: Many AI firms have trained their systems on almost anything found on the open web, what they like to call "publicly available" information -- a category so broad that in some cases it includes known archives of pirated content. The other side: Content creators spanning music, film, visual art, publishing and journalism have sued, and a number of actions are working their way through the courts. My thought bubble: OpenAI's powerful new image generator highlights the risks of giving AI companies total freedom to digest the entire universe of intellectual property.

[3]

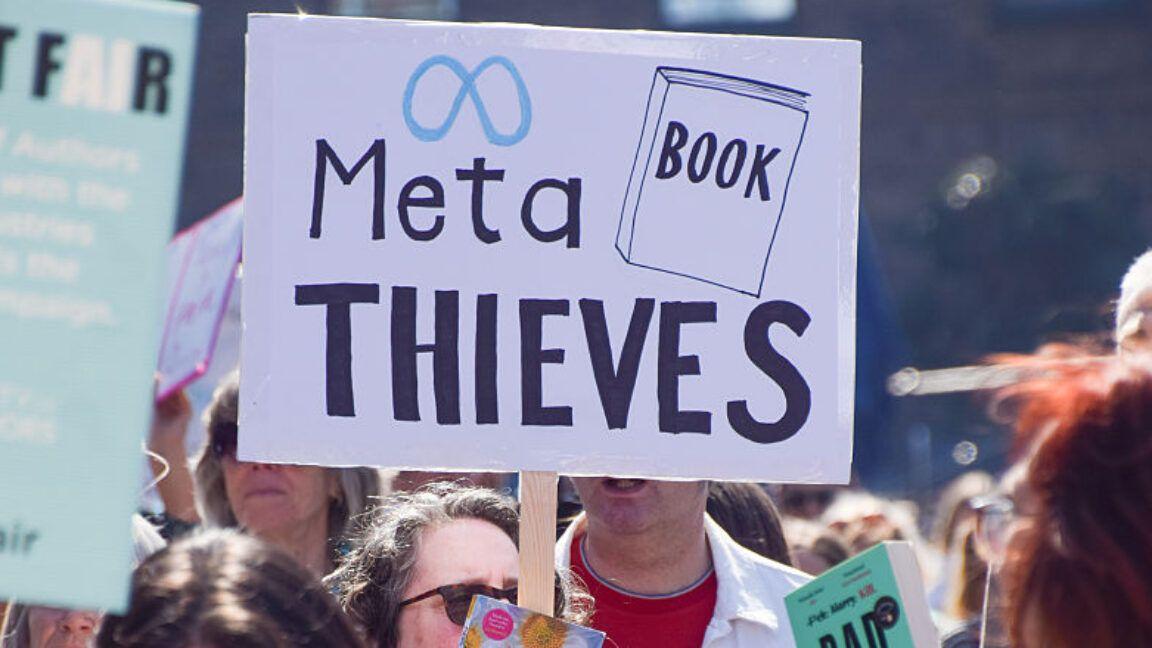

Artists are using a white-hot AI report as a weapon in Meta copyright case

Protesters march on Meta after the company was caught using pirated books for AI training. Credit: Vuk Valcic/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images Plaintiffs in the landmark Kadrey v. Meta case have already submitted the U.S. Copyright Office's controversial AI report as evidence in their copyright infringement suit against the tech giant. Last Friday, the Copyright Office quietly released a "pre-publication version" of its views on the use of copyrighted works to train generative AI models. The consequential report contained bad news for AI companies hoping to claim the fair use legal doctrine as a defense in court. Less than a day after the report was published, Shira Perlmutter, the head of the Copyright Office, was fired by President Donald Trump. It's still unclear exactly why Perlmutter was fired, but the move alarmed some copyright lawyers, as Mashable previously reported. And on May 12, the plaintiffs in Kadrey v Meta, which includes artists and authors such as Junot Diaz, Sarah Silverman, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, submitted the report as an exhibit in their class action lawsuit. The Office's report was the conclusion of a three-part investigation into copyright law and artificial intelligence, which it calls uncharted legal territory. The "Copyright and Artificial Intelligence Part 3: Generative AI Training" report examined exactly the type of legal issues at stake in Kadrey v Meta. While some copyright lawyers and Democratic politicians have speculated the report led to Perlmutter's firing, there are other possible explanations. In a blog post, copyright lawyer Aaron Moss said "it's more likely that the Office raced to release the report before a wave of leadership changes could delay -- or derail -- its conclusions." The report addressed in detail the four factors of the fair use doctrine. Meta and other AI companies are being sued for using copyrighted works to train their AI models, and Meta in particular has claimed this activity should be protected under fair use. The lengthy 113-page report spends around 50 pages delving into the nuances of fair use, citing historic legal cases that ruled for and against fair use. It doesn't goes as far as making any blanket conclusions, but its analysis generally favors copyright holders over AI companies and their unprecedented stockpiling of data for model training. The Copyright Office's stance on the white hot issue doesn't line up with the wishes of Big Tech titans, who have cozied up to the Trump Administration. In general, President Trump has taken a pro-tech approach to AI regulation. The plaintiffs in the Kadrey v. Meta case are clearly hoping the report could tip the scale in their favor. The lawyers who submitted the report as evidence on Monday didn't explain in detail why it was submitted as a "Statement of Supplemental Authority." The brief simply said, "the Report addresses several key issues discussed in the parties' respective motions regarding the use of copyrighted works in the development of generative AI systems and application of the fair use doctrine." The part of the report that's potentially the most damning for Meta is the Copyright Office's assessment of the fourth factor of fair use, which considers the effects on current or future markets. "The use of pirated collections of copyrighted works to build a training library, or the distribution of such a library to the public, would harm the market for access to those works," said the pre-publication version of the report. The analysis also considers possible market dilution for authors. "If thousands of AI-generated romance novels are put on the market, fewer of the human-authored romance novels that the AI was trained on are likely to be sold. Royalty pools can also be diluted," the report stated. In addition, the plaintiffs have argued that Meta's use of piracy to access the authors' books deprived them of licensing opportunities. For its part, Meta argues that its AI model Llama doesn't compete with the authors' market, and that the model's transformative output makes the fair use argument irrelevant. While the report favors the plaintiffs' argument, we don't know if the judge in the case will agree. And because this is a pre-publication version, it could be edited or even rescinded by a future leader at the Copyright Office.

[4]

US copyright verdict offers a glimmer of hope for artists vs AI

AI art may be everywhere, but the legality of AI image generators trained on non-licensed data, and of the images generated by them, is still in doubt. Now, in what sounds like a win for artists, a US Copyright Office report has concluded that the fair use defence does not apply to commercial AI training. But will the office's opinion change anything? That looks particularly doubtful after Donald Trump just fired the Copyright Office's director. According to the 110-page report, "various uses of copyrighted works in AI training are likely to be transformative. The extent to which they are fair, however, will depend on what works were used, from what source, for what purpose, and with what controls on the outputs -- all of which can affect the market. "When a model is deployed for purposes such as analysis or research -- the types of uses that are critical to international competitiveness -- the outputs are unlikely to substitute for expressive works used in training. But making commercial use of vast troves of copyrighted works to produce expressive content that competes with them in existing markets, especially where this is accomplished through illegal access, goes beyond established fair use boundaries." This is a pre-publication version of the report, but the Office said it didn't expect the final version to see any major changes in its conclusions. It goes on to say that practical solutions are needed for uses that may not qualify as fair, noting the emergence of licensing agreements for AI training in certain sectors. The report reads: "Given the robust growth of voluntary licensing, as well as the lack of stakeholder support for any statutory change, the Office believes government intervention would be premature at this time. Rather, licensing markets should continue to develop, extending early successes into more contexts as soon as possible. "In those areas where remaining gaps are unlikely to be filled, alternative approaches such as extended collective licensing should be considered to address any market failure. In our view, American leadership in the AI space would best be furthered by supporting both of these world-class industries that contribute so much to our economic and cultural advancement. "Effective licensing options can ensure that innovation continues to advance without undermining intellectual property rights. These groundbreaking technologies should benefit both the innovators who design them and the creators whose content fuels them, as well as the general public." The report only expresses the Copyright Office's opinion, and it holds back from recommending legislative intervention for now. But the conclusions were welcomed by some campaigners who have been fighting for copyright protection in the face of AI training. Luiza Jarovsky, co-founder of AI Tech and Privacy Academy, wrote on X: "It's GREAT NEWS for content creators/copyright holders, especially as the U.S. Copyright Office's opinion will likely influence present and future AI copyright lawsuits in the U.S." However, how long that influence lasts is in doubt. Just one day after the report's release, Donald Trump's administration fired Register of Copyrights, Shira Perlmutter, who led the US Copyright Office, on Saturday. Joe Morelle, a top Democrat on the House Administration Committee, claimed it was no coincidence that Trump "acted less than a day after she refused to rubber-stamp Elon Musk's efforts to mine troves of copyrighted works to train AI models."

[5]

Copyright Office Says AI Training Without Permission Likely Illegal

The U.S. Copyright Office has concluded that using copyrighted material to train generative AI systems likely amounts to copyright infringement. This includes content scraped from the internet and used in large-scale datasets. The Office says this holds true even if the process is automated or involves billions of data points. The finding appears in the Office's May 2025 report -- the third installment in its ongoing study of AI and copyright. This part focuses specifically on how copyrighted works are used in training, not the outputs these systems produce. Days after the report's publication, President Donald Trump removed Shira Perlmutter from her position as Director of the U.S. Copyright Office. The move raised concerns about political interference in copyright enforcement. While the Office does not propose new laws, it sets out where existing copyright rules apply. It also outlines areas where further legal clarification may be needed. The report does not rule out fair use as a defence. However, it states that most current uses of copyrighted works for AI training are unlikely to qualify. The analysis depends on several factors, including the nature of the copied work, the purpose of the use, how much was taken, and the impact on the market. If AI outputs resemble or replace the work of human creators, fair use becomes more difficult to justify. The Office also warns that wide adoption of a practice does not mean it is lawful. Simply being "common" or "useful" does not make AI training exempt from copyright law. Companies like Open AI have publicly argued that using individual works within massive datasets poses minimal legal risk. While the Copyright Office report does not quote or name specific developers making this claim, it directly addresses the argument. The report states: "The scale of use does not insulate conduct from scrutiny under the Copyright Act." It emphasises that the number of works copied does not change the legal analysis -- if protected content is used, copyright law still applies. The report highlights retrieval-based AI systems. These models do not just train on data once. They pull real-world content into outputs at the moment of generation. Because these systems may reproduce copyrighted content more directly, the Office sees them as higher-risk. The concern is not just training, but output that relies on access to protected works in real time. The Copyright Office notes that most companies do not disclose what data their models are trained on. It says developers rarely explain where content comes from, how it is filtered, or whether copyrighted material is removed. As a result, creators often have no way to know if their work has been used. The Office does not call for mandatory disclosure. But it encourages developers to be more transparent. That includes documentation of training sources, filtering steps, and safeguards against memorisation or copying. Some companies have started to license content for AI training. Adobe's Firefly and Shutterstock are two examples. The report supports these efforts and recommends that voluntary licensing models be allowed to grow. The Office also mentions extended collective licensing. Under this model, creators would be represented by rights organisations. Developers could access content legally, while creators could opt out if they choose. However, the Office does not support compulsory licensing at this time. It says the current market should be allowed to evolve without immediate regulation. The Copyright Office does not call for new laws but recommends that courts continue to define the boundaries of fair use as applied to AI training. It notes that lawsuits involving OpenAI, Meta, and other companies are already underway. The outcomes of these cases, the Office says, will help clarify how existing copyright doctrines apply. If courts fail to resolve these questions, Congress may eventually need to act but for now, the Office sees no immediate need for legislation. This report puts real pressure on how AI companies train their models. If courts agree with the Copyright Office, scraping the internet for training data without permission may no longer be legally defensible. That could force major players like OpenAI and Meta to rethink how they build their systems. Newly surfaced emails have added urgency to one of the most prominent copyright lawsuits in this space. In early 2025, unredacted internal messages revealed that Meta employees had knowingly downloaded and used pirated books from shadow libraries like LibGen and Z-Library to train AI models. According to court filings, the company acquired over 160 terabytes of pirated content, and researchers openly joked about legal risks in internal emails. One engineer even flagged that torrenting from a corporate laptop "doesn't feel right." The Office backs licensing as the right path forward. That gives creators a say in how their work is used and opens the door for more transparent, rights-based approaches to AI development. At the same time, the sudden firing of the Office's director, Shira Perlmutter, has raised red flags. It happened just days after the report came out.

Share

Share

Copy Link

The U.S. Copyright Office's latest report on AI and copyright raises significant concerns about the legality of using copyrighted material for AI training without permission, potentially impacting major tech companies and their AI development practices.

U.S. Copyright Office Challenges AI Companies' Fair Use Claims

The U.S. Copyright Office has released a significant report addressing one of the most contentious issues in the AI industry: the use of copyrighted materials for training AI models. This pre-publication report, the third in a series examining AI and copyright law, suggests that many current practices of AI companies may not be protected under fair use doctrine

1

.Key Findings and Implications

The 108-page report does not entirely rule out fair use for AI training but indicates that many current practices are unlikely to qualify. It emphasizes that the scale of use does not exempt companies from copyright scrutiny, challenging the argument that using individual works within massive datasets poses minimal legal risk

5

.The Office states, "On one end of the spectrum, uses for purposes of noncommercial research or analysis that do not enable portions of the works to be reproduced in the outputs are likely to be fair. On the other end, the copying of expressive works from pirate sources in order to generate unrestricted content that competes in the marketplace ... is unlikely to qualify as fair use"

1

.Impact on Ongoing Lawsuits

This report could significantly influence ongoing lawsuits against AI companies. In a swift move, plaintiffs in the Kadrey v. Meta case, which includes prominent authors like Sarah Silverman and Ta-Nehisi Coates, have already submitted the report as evidence in their class action lawsuit

3

.Licensing and Market Solutions

The Copyright Office encourages the development of licensing markets for AI training data. It notes the emergence of voluntary licensing agreements in certain sectors and suggests that extended collective licensing could be considered to address market failures

4

.Political Controversy

The release of this report has been overshadowed by political controversy. Shortly after its publication, Shira Perlmutter, the head of the Copyright Office, was fired by President Donald Trump

2

. This move has raised concerns about potential political interference in copyright enforcement.Related Stories

Industry Reactions and Future Implications

The report's conclusions have been welcomed by some campaigners fighting for copyright protection. Luiza Jarovsky, co-founder of AI Tech and Privacy Academy, called it "GREAT NEWS for content creators/copyright holders"

4

.However, the tech industry, which has been pushing for fair use exceptions, may face significant challenges. Companies like OpenAI, Meta, and others involved in ongoing lawsuits may need to reconsider their AI training practices

5

.Conclusion

While the Copyright Office's report is not law, it provides crucial guidance on how the agency views copyright protections in the AI era. As courts continue to grapple with these issues, this report could play a significant role in shaping the future of AI development and copyright law in the United States.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[4]

Related Stories

Judges Side with AI Companies in Copyright Cases, but Leave Door Open for Future Challenges

25 Jun 2025•Policy and Regulation

Legal Battles Over AI Training: Courts Rule on Fair Use, Authors Fight Back

15 Jul 2025•Policy and Regulation

OpenAI and Google Push for Relaxed Copyright Laws in AI Development

14 Mar 2025•Policy and Regulation

Recent Highlights

1

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

2

Demis Hassabis predicts AGI in 5-8 years, sees new golden era transforming medicine and science

Technology

3

Nvidia and Meta forge massive chip deal as computing power demands reshape AI infrastructure

Technology