AI Art Sparks Debate: From Harold Cohen's AARON to Ai-Da's Million-Dollar Painting

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Electric Dreams at Tate Modern -- when artists embraced the power of technology

Harold Cohen was already an established painter when he started experimenting with computers in the late 1960s. This was when he began building AARON, a rudimentary AI that could draw semi-autonomously. Unlike today's AI image generators, which make pictures based on analysing real images, AARON's drawings were based purely on the mathematical rules Cohen programmed. Over the years, he continued to improve AARON, teaching it to draw with imprecise strokes to mimic a human hand, to detect shapes and shade them in, even to physically draw with the help of a device called a "turtle" that would scurry across the canvas making marks. One 1979 artwork is a playful piece of abstraction, reminiscent of a child's drawing of a fantastical map. It is pretty, and looks at home on a gallery wall. Cohen would continue to tinker and collaborate with AARON for the rest of his life. Now is a fraught moment at the confluence of fine art and cutting-edge technology. On the one hand, modern technology is being used to ever more sophisticated and captivating effect by artists. Yet simultaneously, anxiety around that same technology grows louder in artistic discourse and within the artworks themselves. With hindsight, Harold Cohen's story looks like a parable, a possibility for an artist to neither dominate nor fear encroaching technology, but to grow alongside it. His is one of many little-known stories told in Tate Modern's new exhibition Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet (opening on November 28), which brings together work from more than 70 artists inspired by and creating art with technology between the end of the second world war and the dawn of the internet as we know it in the early 1990s. This spans a period of immense technological development during which, as curator Val Ravaglia points out, the computer evolved from being the size of an entire room to a discreet box that could fit on or under a desk. The artists who harnessed and responded to this rapid social change provide an intriguing precedent for many of the conversations playing out in the art world today. A large part of the motivation for the exhibition is to pay tribute to an often overlooked chapter in art history. While movements such as Pop art and Minimalism gained traction in the mainstream, an international group of like-minded artists gathered around the hub of Zagreb in present-day Croatia, to share work inspired by scientific and mathematical ideas. They became known by the name of their exhibition series, New Tendencies, presenting art that might today be classified as kinetic or optical art; works that either literally move or give the illusion of movement. The group became a centre of gravity for other collectives interested in similar ideas, such as the German group Zero, founded in the 1950s by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene, and Italy's Arte Programmata, who were inspired by mathematics and had a fan in Umberto Eco, who wrote the catalogue for their first show. The Tate exhibition also shines a spotlight on the influential 1968 exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity at London's ICA, the first large-scale exhibition dedicated to the computer as both medium and inspiration. Footage from the show displays moving sculptures, video synthesisers, and a rather dated-looking robot that resembles an off-brand Dalek. Art inspired by maths sounds as if it might be cold, austere and inaccessible. Ravaglia explains, however, that the New Tendencies artists saw their work as a way to make complex scientific ideas digestible, arresting, even beautiful. "You don't need to think about what you're seeing, it catches you and acts within your synapses first," she says. "You enjoy the form first, then the rest comes later." These artists provided a blueprint for the monumental, data-driven installations by artists such as Refik Anadol and Ryoki Ikeda, who display internationally today. Much work in the exhibition hits the senses first. There is one of David Medalla's "Sand Machines", which drags beads across a patch of sand to create an ever-changing Zen garden, and Brion Gysin's "Dreamachine", a revolving lamp that creates optical patterns if you stare at it with eyes closed. The "Square Tops" sculpture by Wen-Ying Tsai, which resembles a field of elegant robotic mushrooms, undulates with lights that change frequency in response to the sound made by the people in the room. Visitors are encouraged to interact with the work by clapping, singing, or playing music out loud. The exhibition shows that artists have long been early adopters of new technologies, with some repeatedly evolving single works as technology developed. Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez's piece "Chromointerferent Environment" transforms the gallery into an optical illusion where coloured parallel lines flash psychedelically across the walls. Between 1974 and 2009 he repeatedly adapted the work using novel technologies, moving from painted panels to film, then video, and finally computer-generated imagery in its current iteration. Artists from this period offered a range of visions of the technological future in which we now live. Some gathered under the banner of sci-fi utopianism, as outlined in Richard Brautigan's 1967 poem "All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace", in which we live in "a cybernetic meadow/where mammals and computers/live together in mutually/programming harmony." Others were more critical. Some artists wrote about their awareness that the technology they were using was originally developed for military purposes, and were keen to reappropriate the objects as art and sever them from this destructive history. Particularly prescient was Gustav Metzger, who spoke of the potential environmental damage caused by technological advancements, a point that feels burningly relevant today as we begin to grapple with the energy and water resources consumed by products such as ChatGPT. "Metzger talks about how artists should be wary of embracing technology with unbridled optimism," says Ravaglia. "It was important for them to be part of the conversation, to steer technology toward more humanistic values and not become puppets in the hands of a technological industry that would want to use artists to showcase their wares." Some of the vintage technology in this exhibition may look quaint today, but many of its themes address urgent contemporary conversations facing artists. "For example, some now believe that generative AI will replace creativity, that it will kill art," says Ravaglia, "but in these works we see that the adoption of AI to make artworks has a history. There's many examples in the past of artists that have collaborated with AIs, not just let them take over and run away with their ability to make images." Harold Cohen was one such example. He continued, until his death in 2016, to improve AARON the drawing AI, later programming it to be able to draw figurative images such as humans and plants, and ultimately enabling it to colour in its own drawings. "This was the point where he said: I don't like this too much. Where's my input?" says Ravaglia. Cohen loved to colour in his own work, so he decided to take away AARON's ability to do so, to ensure that their work would remain a collaboration that would still bring him pleasure. He wanted to ensure, until the end, that the artist stayed in the picture.

[2]

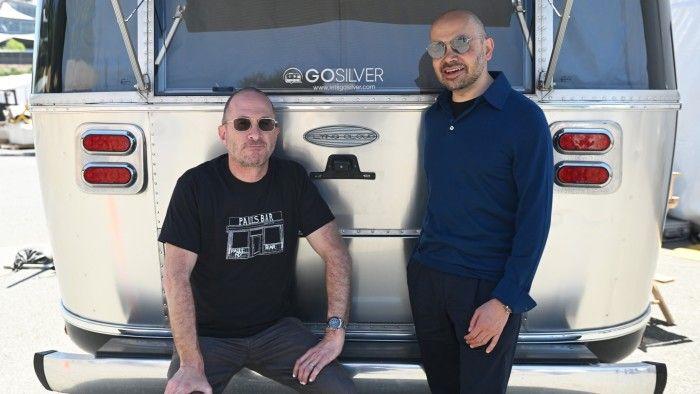

Why you're wrong about AI art, according to the Ai-Da robot that just made a $1 million painting

Science fiction promised us robot butlers, but it seems they rather fancy themselves as artists instead. And who can blame them? On November 7, a painting of the mathematician Alan Turing by an AI-powered robot called Ai-Da sold at auction for a cool $1,084,000 (around £865,000). That's a more appealing lifestyle than having to sprint around a Boston Dynamics assault course. The Sotheby's auction house said Ai-Da is "the first humanoid robot artist to have an artwork sold at auction." It probably also set the record the most online grumbling about a painting, which is understandable - after all, shouldn't robots be sweeping up and making the tea, while we artfully dab at the canvases? Naturally, the Ai-Da robot and its maker Aidan Meller don't agree that art should be ring-fenced by humans. As Marvin from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy once noted: "Here I am, brain the size of a planet and they ask me to take you down to the bridge. Call that job satisfaction? 'Cos I don't." But rather than rely on Douglas Adams to fill in the blanks, we asked Ai-Da and Meller what they'd say to those who are skeptical about AI-generated art - and what the landmark 'A.I. God' painting means for the future of creativity... Ai-Da herself usually prefers to let her art do the talking. When we asked her why she paints her answer was: "The key value of my work is in its capacity to serve as a catalyst for dialogue about emerging technologies". Fortunately, her creator Aidan Meller, a gallerist and veteran of the art world, was more forthcoming on why team Ai-Da doesn't think the painting or her work should be considered a threat to human artists. "Contemporary art has always provoked discussions about what art is and Ai-Da and her work is no different," Meller told us. "Just her existence is quite controversial for the art world," he added. Given the reaction to the 'A.I. God' painting, her presence is also pretty controversial for amateur artists, too. Meller prefers to see Ai-Da as the natural successor to the artistic disruptors of the past. "History is littered with artists that society called "non-artists". Everyone from Picasso to Matisse challenged people's idea of what art was during their time. Because it didn't fit into their conception of what art should be," he told us. "Duchamp challenged the idea of what art could be by putting a urinal in an art gallery and changed the future of art. The Ai-Da Robot challenges the idea of what an artist can be, by creating art using AI technology and creative agency," he added. But how exactly is AI art created, in Ai-Da's case, and are humanoid robots a necessary part of it gaining mainstream acceptance? After all, there's a difference between hitting the 'create' button in the best AI art generators and seeing a robot physically apply strokes to a canvas. In reality, Ai-Da's work is a collaboration between AI, robots and humans, with the latter still a very necessary part of the process. "We had a discussion with Ai-Da about what she might paint in relation to the concept of "AI for Good", and she came up with Alan Turing," Meller explained. "We then showed Ai-Da Robot an image of Alan Turning, which Ai-Da responded to by creating the artwork. She painted 15 images of Alan Turing and then selected three to be combined together to form A.I. God," he added. Those three portraits were uploaded to a computer and then printed on a canvas, with Ai-Da then applying marks and textures to finish the painting. Some final bits of texture were added by human assistants, in the parts of the canvas where Ai-Da couldn't reach. The finished artwork has more in common with Warhol's 'Factory' process, then, rather than a decade-long Da Vinci masterpiece. But what does this all mean for the future of art? Ai-Da's creator definitely isn't on the side of the AI cynics like Linux founder Linus Torvalds, who recently slammed AI as "90% marketing and 10% reality". "I think the response to the painting at auction shows that people understand the importance and power of AI in how it is shaping the world we live in and all of our futures," Aidan Meller said. "The auction shows that AI is on the rise and it is going to change society enormously". The painting's landmark price tag, which shattered its pre-auction estimate of around around $120,000-$180,000 (£100,00-£150,000) suggests something has shifted in art collecting, too. "I think it does also mean that the art world is beginning to accept that AI art is here to stay. It also shows that creativity comes in many forms and that AI has the ability to be creative and to add value to the world," Meller added. That last point remains up for debate and will remain so indefinitely. The makers of the popular digital art app Procreate, for example, recently said it will never embrace generative AI. In fact, they went a bit harder than that, with CEO James Cuda stating: "I really f***ing hate generative AI. I don't like what's happening in the industry and I don't like what it's doing to artists." Clearly, Ai-Da and her process is few steps beyond the basic generative AI we're seeing bolted onto consumer apps, but it could be a tough battle to win over skeptics. Then again, Ai-Da's creator says the point of the robot is to stimulate debate rather than convince you to swap sides... For many, Ai-Da herself is the art story rather than the $1 million painting she co-created. That's something Meller echoed when we asked him why Ai-Da was created in the first place. "The key value of Ai-Da as a robot artist is not necessarily in acceptance, but in the capacity to serve as a catalyst for dialogue about emerging technologies," he said. Clearly, the art world thinks there's a monetary value in the results produced by the project, but Meller thinks it goes beyond that. "One purpose of contemporary art is to ask questions of our time and to challenge the status quo, creating debate," he said. "So art created by an AI-powered robot was a good platform to engage audiences into a discussion around the ethical issues surrounding the development of AI technology and our response as a society." Ai-Da herself isn't new - we first covered the portrait artist back in 2019 - but the rapid development of AI models has helped transform her skills and make her the face of a hot debate that is sparking controversies on a weekly basis. And Meller admits that Ai-Da is as much as a conduit for debate as an established artist. "We are currently going through the fourth Industrial revolution, and this is resulting in extreme shifts in both technology and human behavior globally," he said. "So the heart of the project is a robot artist that explores the impact new technologies are having on society". The core of the Ai-Da debate revolves around the question of whether there's something unique, even sacrosanct, about art. For many, art is a communication between humans - the creator and audience - which gives AI-driven art a hollow air of meaninglessness. But Meller disagrees, seeing Ai-Da's approach as the latest development of how humans are using technology. "Many people look at Ai-Da and think about her being an AI-powered robot, but in many ways humans are becoming more robotic in our use of technology," he said. "We are transferring our decision-making and our agency onto machines, and in lots of ways as humans we are merging with machines and becoming cyborgs ourselves" he observed, pointing to smartphones as the obvious example. "When sat-nav came out, we didn't quite trust it, but now we wouldn't go anywhere without it. AI has infiltrated every part of our lives, from what work we will do, what news we watch, what kind of partner we have, what kind of baby even we might want to have," he added. "By painting this picture of Alan Turing, Ai-Da Robot is really digging into all of these big ethical issues." While some will flinch at parallels being drawn between sat-navs and paintings, there's no doubt Ai-Da has succeeded in reviving a debate that's as old as at art itself. The obvious example is the invention of photography in the mid-1800s, which shocked painters who dismissed the mechanized 'imitation' of their painterly hand as an art form. Ultimately, photography and art learned to not only co-exist, but to develop a symbiotic relationship. The French painter Degas was influenced by photography, while holding a contempt for the commercialized industry it became. As 'pictorialist' photographers sought to imitate traditional watercolors, painters moved towards impressionism. Will AI-driven art and human artists do the same, rather than seeking to extinguish each other? History would suggest so. Whatever the financial or artistic merits of the 'A.I. God' painting, it's certainly a lightning rod for debate - and whichever side of the debate you're on, it's one that's worth engaging in. As the Hungarian artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy said in the early 1900s, "anyone who fails to understand photography will be one of the illiterates of the future". AI-driven art is clearly here to stay and, while we may eventually get our robot butlers, it'll probably pay to engage with their artistic cousins in the meantime.

Share

Share

Copy Link

The intersection of AI and art gains prominence with Ai-Da's $1 million painting, while a Tate Modern exhibition explores the historical relationship between technology and creativity.

AI Art Takes Center Stage with Million-Dollar Painting

In a groundbreaking moment for artificial intelligence in the art world, a painting of mathematician Alan Turing created by AI-powered robot Ai-Da sold at auction for $1,084,000

2

. This sale marks a significant milestone as the first artwork by a humanoid robot artist to be sold at auction, sparking intense debate about the role of AI in creative processes.The Evolution of AI in Art: From AARON to Ai-Da

The intersection of art and technology is not a new phenomenon. Harold Cohen, an established painter, began experimenting with computers in the late 1960s, creating AARON, a rudimentary AI capable of semi-autonomous drawing

1

. Unlike today's AI image generators, AARON's drawings were based on mathematical rules programmed by Cohen, showcasing an early collaboration between human creativity and machine capabilities.Tate Modern's "Electric Dreams" Exhibition

Tate Modern's new exhibition, "Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet," explores the historical relationship between art and technology from the end of World War II to the early 1990s

1

. The exhibition features works from over 70 artists who embraced and responded to rapid technological advancements, providing context for current discussions about AI in art.The Process Behind Ai-Da's Artwork

Ai-Da's creative process involves collaboration between AI, robots, and humans. For the Turing painting, Ai-Da generated 15 images based on a photograph, from which three were selected and combined

2

. The robot then applied marks and textures to the printed canvas, with human assistants adding final touches where Ai-Da couldn't reach.Debate and Controversy in the Art World

The sale of Ai-Da's painting has intensified the ongoing debate about AI's role in art. While some view AI art as a natural progression in the history of artistic innovation, others express concern about its impact on human creativity. Aidan Meller, Ai-Da's creator, argues that AI art is here to stay and that creativity can take many forms

2

.Related Stories

Historical Context of Technological Art

The Tate Modern exhibition highlights how artists have long been early adopters of new technologies. For instance, Carlos Cruz-Diez's "Chromointerferent Environment" evolved from painted panels to computer-generated imagery over several decades

1

. This historical perspective provides insight into the current AI art movement.The Future of AI in Art

As AI continues to develop, its role in art creation and the art market is likely to expand. The record-breaking sale of Ai-Da's painting suggests a growing acceptance of AI-generated art in the collector's market. However, the debate about the nature of creativity and the value of AI-generated art is far from settled, with some artists and companies, like Procreate, strongly opposing the use of generative AI in art

2

.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Meta strikes up to $100 billion AI chips deal with AMD, could acquire 10% stake in chipmaker

Technology

3

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with supply chain risk label over AI safeguards for military use

Policy and Regulation