AI Revolutionizes Paleontology: Ancient Tegu Fossil Discovered in Florida

3 Sources

3 Sources

[1]

From prehistoric resident to runaway pet: First tegu fossil found in the U.S.

Originally from South America, the charismatic tegu made its way to the United States via the pet trade of the 1990s. After wreaking havoc in Florida's ecosystems, the exotic lizard was classified as an invasive species. But a recent discovery from the Florida Museum of Natural History reveals the reptiles are no strangers to the region -- tegus were here millions of years before their modern relatives arrived in pet carriers. Described in a new study in the Journal of Paleontology, this breakthrough came from a single, half-inch-wide vertebra fossil that was unearthed in the early 2000s and puzzled scientists for the next 20 years. Jason Bourque, now a fossil preparator in the museum's vertebrate paleontology division, came across the peculiar fossil in the museum's collection freshly out of graduate school. "We have all these mystery boxes of fossil bones, so I was digging through, and I kept coming across this one vertebra," Bourque said. "I could not figure out what it was. I put it away for a while. Then I'd come back and say: Is it a lizard? Is it a snake? In the back of my mind for years and years, it just sat there." The vertebra had been found in a fuller's earth clay mine just north of the Florida border, after a tipoff from the local work crew prompted a visit from the museum's paleontologists. There was just one catch: The mine was slated to close, and its quarry, along with any exposed fossils, would soon be filled in. Working against a deadline, the scientists excavated as many fossils as they could and brought them back to the museum, where the vertebra sat in storage, its identity unresolved. Years later, Bourque stumbled across an image of tegu vertebrae while looking through studies for a new research paper. "I saw the tegu, and I just knew right away that's what this fossil was," Bourque said. Today, tegus are of particular interest to Florida's wildlife biologists and conservationists. Their bold patterns and docile attitudes make them attractive pets, but that often changes once they reach nearly 5 feet in length and weigh 10 pounds. Exotic pets have a knack for slipping free -- or being released -- into the wild, where they can take a heavy toll on native ecosystems. This is the case with modern tegus in Florida. But until this point, there was no record of prehistoric tegus in North America. Bourque needed evidence to back up his revelation. Paleontologists typically work with multiple bones to identify an animal, but Bourque just had a single vertebra. He recruited his colleague, Edward Stanley, director of the museum's digital imaging laboratory, who saw an opportunity to try out a new, machine learning technique -- one that doesn't rely on a paleontologist's decades of specialized knowledge. With a CT scan of the unidentified fossil, Stanley carefully measured and landmarked each bump, hole and furrow of the fossil. Next, he needed vertebrae from other tegus and related lizards for comparison. Fortunately, the team had access to an abundance of specimens thanks to the museum's openVertebrate (oVert) project, a free, online collection of thousands of 3D images of vertebrates. Instead of measuring these images by hand, Stanley used a technique developed by Arthur Porto, the museum's curator of artificial intelligence for natural history and biodiversity, to automatically recognize and fit the corresponding landmarks onto more than 100 vertebrae images from the database. By comparing the data of all their shapes, he determined the fossil matched the other tegus and pinpointed its original position to the middle of the lizard's spinal column. While the fossil was unmistakably a tegu vertebra, it wasn't an exact match with any of the specimens in the database. This meant the team had uncovered a news species, which they named Wautaugategu formidus. Wautauga is the name of a forest near the mine where the fossil was discovered. Although the word's origin is unclear, it is thought to mean "land of the beyond," which Bourque and Stanley found fitting for the long-extinct species, that, despite having ancestral ties to South America, ended up in present-day Georgia. "Formidus," a Latin word meaning "warm," alludes to the reason these lizards likely wound up in the southeastern United States in the first place. The fossil is from the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum, a particularly warm period in Earth's geologic history. At the time, sea levels were significantly higher than today, and with most of Florida underwater, the historic coastline would have been near the site of the fossil bed. Tegus are terrestrial lizards, but they are strong swimmers. The warm climate may have tempted them to travel from South America into present-day Georgia, but the region did not remain hospitable for long. "We don't have any record of these lizards before that event, and we don't have any records of them after that event. It seems they were here just for a blip, during that really warm period," Bourque said. The tegus would likely have struggled and ultimately disappeared as global temperatures cooled. Like other egg-laying animals, their reproduction is highly dependent on temperature, and the cold may have limited their ability to produce or hatch eggs. Finding more tegu fossils may help demystify the prehistoric lizard's brief stint in North America. "I'm ready to go up to the Panhandle and try to find more fossil sites along the ancient coastal ridge near the Florida-Georgia border," Bourque said. Stanley, meanwhile, hopes the next find won't languish in storage. The combination of 3D modeling and artificial intelligence to identify fossils without relying on decades of specialized knowledge could dramatically speed up the process. With open access to data worldwide, it could even lead to a global database for fossil identification. "There are boxes full, shelves full, of fossils that are unsorted because it requires a huge amount of expertise to identify these things, and nobody has time to look through them comprehensively," Stanley said. "This is a first step towards some of that automation, and it's very exciting see where it goes from here."

[2]

From prehistoric resident to runaway pet: First tegu fossil found in the US

Originally from South America, the charismatic tegu made its way to the United States via the pet trade of the 1990s. After wreaking havoc in Florida's ecosystems, the exotic lizard was classified as an invasive species. But a recent discovery from the Florida Museum of Natural History reveals the reptiles are no strangers to the region -- tegus were here millions of years before their modern relatives arrived in pet carriers. Described in a study in the Journal of Paleontology, this breakthrough came from a single, half-inch-wide vertebra fossil that was unearthed in the early 2000s and puzzled scientists for the next 20 years. Jason Bourque, now a fossil preparator in the museum's vertebrate paleontology division, came across the peculiar fossil in the museum's collection when he was freshly out of graduate school. "We have all these mystery boxes of fossil bones, so I was digging through, and I kept coming across this one vertebra," Bourque said. "I could not figure out what it was. I put it away for a while. Then I'd come back and say, Is it a lizard? Is it a snake? In the back of my mind for years and years, it just sat there." The vertebra had been found in a fuller's earth clay mine just north of the Florida border, after a tipoff from the local work crew prompted a visit from the museum's paleontologists. There was just one catch: The mine was slated to close, and its quarry, along with any exposed fossils, would soon be filled in. Working against a deadline, the scientists excavated as many fossils as they could and brought them back to the museum, where the vertebra sat in storage, its identity unresolved. Years later, Bourque stumbled across an image of tegu vertebrae while looking through studies for a new research paper. "I saw the tegu, and I just knew right away that's what this fossil was," Bourque said. Today, tegus are of particular interest to Florida's wildlife biologists and conservationists. Their bold patterns and docile attitudes make them attractive pets, but that often changes once they reach nearly 5 feet in length and weigh 10 pounds. Exotic pets have a knack for slipping free -- or being released -- into the wild, where they can take a heavy toll on native ecosystems. This is the case with modern tegus in Florida. But until this point, there was no record of prehistoric tegus in North America. Bourque needed evidence to back up his revelation. Paleontologists typically work with multiple bones to identify an animal, but Bourque had just a single vertebra. He recruited his colleague, Edward Stanley, director of the museum's digital imaging laboratory, who saw an opportunity to try out a new machine-learning technique -- one that doesn't rely on a paleontologist's decades of specialized knowledge. With a CT scan of the unidentified fossil, Stanley carefully measured and landmarked each bump, hole and furrow of the fossil. Next, he needed vertebrae from other tegus and related lizards for comparison. Fortunately, the team had access to an abundance of specimens thanks to the museum's openVertebrate (oVert) project, a free, online collection of thousands of 3D images of vertebrates. Instead of measuring these images by hand, Stanley used a technique developed by Arthur Porto, the museum's curator of artificial intelligence for natural history and biodiversity, to automatically recognize and fit the corresponding landmarks onto more than 100 vertebrae images from the database. By comparing the data of all their shapes, he determined the fossil matched the other tegus and pinpointed its original position at the middle of the lizard's spinal column. While the fossil was unmistakably a tegu vertebra, it wasn't an exact match with any of the specimens in the database. This meant the team had uncovered a new species, which they named Wautaugategu formidus. Wautauga is the name of a forest near the mine where the fossil was discovered. Although the word's origin is unclear, it is thought to mean "land of the beyond," which Bourque and Stanley found fitting for the long-extinct species, that -- despite having ancestral ties to South America -- ended up in present-day Georgia. "Formidus," a Latin word meaning "warm," alludes to the reason these lizards likely wound up in the southeastern United States in the first place. The fossil is from the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum, a particularly warm period in Earth's geologic history. At the time, sea levels were significantly higher than today, and with most of Florida underwater, the historic coastline would have been near the site of the fossil bed. Tegus are terrestrial lizards, but they are strong swimmers. The warm climate may have tempted them to travel from South America into present-day Georgia, but the region did not remain hospitable for long. "We don't have any record of these lizards before that event, and we don't have any records of them after that event. It seems they were here just for a blip, during that really warm period," Bourque said. The tegus would likely have struggled and ultimately disappeared as global temperatures cooled. Like other egg-laying animals, their reproduction is highly dependent on temperature, and the cold may have limited their ability to produce or hatch eggs. Finding more tegu fossils may help demystify the prehistoric lizard's brief stint in North America. "I'm ready to go up to the Panhandle and try to find more fossil sites along the ancient coastal ridge near the Florida-Georgia border," Bourque said. Stanley, meanwhile, hopes the next find won't languish in storage. The combination of 3D modeling and artificial intelligence to identify fossils without relying on decades of specialized knowledge could dramatically speed up the process. With open access to data worldwide, it could even lead to a global database for fossil identification. "There are boxes full, shelves full, of fossils that are unsorted because it requires a huge amount of expertise to identify these things, and nobody has time to look through them comprehensively," Stanley said. "This is a first step towards some of that automation, and it's very exciting to see where it goes from here."

[3]

Ancient tegu lizard discovered in Florida using artificial intelligence - Earth.com

When we think of Florida's wildlife, charismatic reptiles like alligators and snakes often come to mind. Yet, few would associate the tegu, a South American lizard known for its striking patterns and imposing size, with prehistoric North America. The tegu's invasion of Florida in the 1990s via the pet trade wreaked havoc on the region's ecosystems, earning the lizard a reputation as a notorious invasive species. However, a recent breakthrough from the Florida Museum of Natural History reveals that the tegus' connection to North America stretches far beyond their modern-day escapades. The discovery began in the early 2000s, when Jason Bourque, a fresh graduate, stumbled upon a peculiar vertebra fossil in the museum's collection. It was only half an inch wide, but its shape gnawed at him. Despite its unassuming size, the fossil refused to be ignored. "We have all these mystery boxes of fossil bones, so I was digging through, and I kept coming across this one vertebra," Bourque said. "I could not figure out what it was. I put it away for a while. Then I'd come back and say: Is it a lizard? Is it a snake? In the back of my mind for years and years, it just sat there." Long before Bourque's moment of realization, the fossil had narrowly escaped permanent burial. A fuller's earth clay mine near the Florida border was closing down, its quarry set to be filled in. Paleontologists rushed to collect fossils, knowing they might never get another chance. The fossil made it to the Florida Museum of Natural History, where it languished in storage. There, it became another forgotten bone in a sea of unsorted fossils. But Bourque never quite let it go. Years later, during a late-night research session, an image of a tegu vertebra stopped him cold. "I saw the tegu, and I just knew right away that's what this fossil was," he said. That recognition ignited a new quest -- proving it. To turn his hunch into scientific fact, Bourque needed evidence. A single vertebra wasn't enough, but identifying it through traditional methods would be laborious and time-consuming. Enter Edward Stanley, the museum's digital imaging director. Stanley saw an opportunity to test a new machine learning technique that bypassed the old, painstaking processes. Stanley scanned the fossil using a CT machine, creating a 3D model that captured every curve, ridge, and depression. Next, he needed modern tegu vertebrae for comparison. Luckily, the museum's openVertebrate (oVert) project provided a wealth of 3D vertebrate images. Stanley then teamed up with Arthur Porto, the museum's AI curator. Porto's technique automated the process, pinpointing the fossil's exact position in the lizard's spinal column. Each bump and groove aligned perfectly with modern tegus - except for one key difference. The fossil wasn't an exact match for any known tegu species. Instead, it belonged to a previously unknown species, now named Wautaugategu formidus. The name "Wautauga" references a nearby forest, a nod to the site where the fossil was found. "Formidus," meaning "warm" in Latin, hints at the creature's era - the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum, a period of intense heat. Back then, Florida was mostly underwater. The coastline stretched to what is now Georgia, creating a warm, swampy habitat. Tegus, skilled swimmers, likely ventured northward, taking advantage of the balmy climate. But the warmth didn't last. Global temperatures dropped after the Miocene heat spike. The once-welcoming shores of prehistoric Georgia turned cold, and Wautaugategu formidus faced a new reality. Cold-blooded and dependent on warm conditions for reproduction, the lizard couldn't adapt. "We don't have any record of these lizards before that event, and we don't have any records of them after that event. It seems they were here just for a blip, during that really warm period," Bourque said. The cooling temperatures likely doomed the species, leaving behind nothing but a solitary vertebra to whisper its story. While Wautaugategu formidus may have vanished, its discovery marks a pivotal moment for paleontology. Stanley believes AI could transform fossil research, allowing scientists to scan, compare, and identify bones without years of specialized training. "There are boxes full, shelves full, of fossils that are unsorted because it requires a huge amount of expertise to identify these things, and nobody has time to look through them comprehensively," Stanley said. "This is a first step towards some of that automation, and it's very exciting see where it goes from here." The implications are staggering. With open-access databases like oVert, fossils from disparate collections could be cross-referenced, uncovering connections scientists never dreamed of. For Bourque, the discovery of Wautaugategu formidus is a tantalizing hint of what might still be hiding in the ancient coastal ridge near the Florida-Georgia border. He's already planning his next expedition, hoping to find more fossils that could fill in the gaps of the tegu's North American saga. "I'm ready to go up to the Panhandle and try to find more fossil sites along the ancient coastal ridge near the Florida-Georgia border," he said. But even if Bourque finds more fossils, the challenge remains - identifying them. The tegu vertebra only came to light because of a chance encounter and a spark of recognition. AI could eliminate that element of luck, speeding up the process and allowing scientists to focus on what truly matters: the stories behind the bones. For years, a half-inch vertebra sat unnoticed in the museum's collection, its potential obscured by its small size. Now, that fossil has become a key to a lost world, a clue to a forgotten lineage of lizards that once swam across the ancient seas. The journey from storage box to scientific breakthrough underscores the importance of reexamining old finds with fresh eyes - and new technology. The future of paleontology may not lie in the ground, but in data, algorithms, and a global network of researchers, all united in the quest to uncover Earth's ancient past. For now, Wautaugategu formidus remains a single bone, a lone survivor of a vanished world. But as AI and digital databases expand, more fossils may step out of the shadows, ready to tell their tales. Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Share

Share

Copy Link

A groundbreaking discovery of a prehistoric tegu lizard fossil in Florida, identified using AI and machine learning techniques, reshapes our understanding of North American paleontology and demonstrates the potential of AI in scientific research.

Prehistoric Tegu Fossil Unearthed in Florida

In a groundbreaking discovery, paleontologists at the Florida Museum of Natural History have identified the first known tegu lizard fossil in North America, dating back millions of years before the species' modern introduction as an invasive pet

1

2

. This finding not only reshapes our understanding of prehistoric fauna in the region but also showcases the potential of artificial intelligence in paleontological research.The Journey of Discovery

The story begins with a single, half-inch-wide vertebra fossil unearthed in the early 2000s from a fuller's earth clay mine near the Florida-Georgia border. For two decades, this small bone puzzled scientists, including Jason Bourque, now a fossil preparator at the museum

1

2

3

.Bourque's eureka moment came years later when he stumbled upon an image of tegu vertebrae during research:

"I saw the tegu, and I just knew right away that's what this fossil was," Bourque said

1

.AI-Powered Paleontology

To confirm his hunch, Bourque collaborated with Edward Stanley, director of the museum's digital imaging laboratory. They employed a novel machine learning technique that doesn't rely on decades of specialized knowledge

1

2

.The process involved:

- Creating a CT scan of the fossil

- Carefully measuring and landmarking its features

- Utilizing the museum's openVertebrate (oVert) project, a free online collection of 3D vertebrate images

- Applying an AI technique developed by Arthur Porto, the museum's curator of artificial intelligence, to automatically recognize and fit corresponding landmarks onto over 100 vertebrae images

1

2

3

This innovative approach allowed the team to confirm the fossil's identity and pinpoint its original position in the lizard's spinal column.

A New Species Emerges

The analysis revealed that the fossil belonged to a previously unknown species, which the team named Wautaugategu formidus. The name combines "Wautauga," referring to a nearby forest, with "formidus," Latin for "warm," alluding to the warm climate during which these lizards lived

1

2

3

.Related Stories

Climate Change and Prehistoric Migration

The fossil dates back to the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum, a particularly warm period in Earth's history. During this time, higher sea levels submerged most of Florida, creating a coastline near present-day Georgia

1

2

.Bourque explains the significance:

"We don't have any record of these lizards before that event, and we don't have any records of them after that event. It seems they were here just for a blip, during that really warm period,"

1

2

3

.As the climate cooled, the tegus likely struggled to adapt, eventually disappearing from the region.

The Future of Paleontology

This discovery highlights the potential of AI and machine learning in paleontological research. Stanley believes these techniques could dramatically speed up the process of identifying fossils:

"There are boxes full, shelves full, of fossils that are unsorted because it requires a huge amount of expertise to identify these things, and nobody has time to look through them comprehensively," Stanley said. "This is a first step towards some of that automation, and it's very exciting to see where it goes from here."

3

The combination of 3D modeling and AI could revolutionize the field, allowing researchers to uncover connections and make discoveries at an unprecedented pace

1

2

3

.As Bourque prepares for future expeditions to find more tegu fossils, the scientific community eagerly anticipates how AI will continue to transform our understanding of prehistoric life and accelerate discoveries in paleontology

1

2

3

.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Scientists Launch DinoTracker, an AI App That Identifies Dinosaur Footprints in Seconds

27 Jan 2026•Science and Research

New AI method tackles century-old challenge of identifying which dinosaur made which footprints

06 Feb 2026•Science and Research

AI and International Collaboration Revive Native Red-Legged Frogs in Southern California

27 Aug 2025•Science and Research

Recent Highlights

1

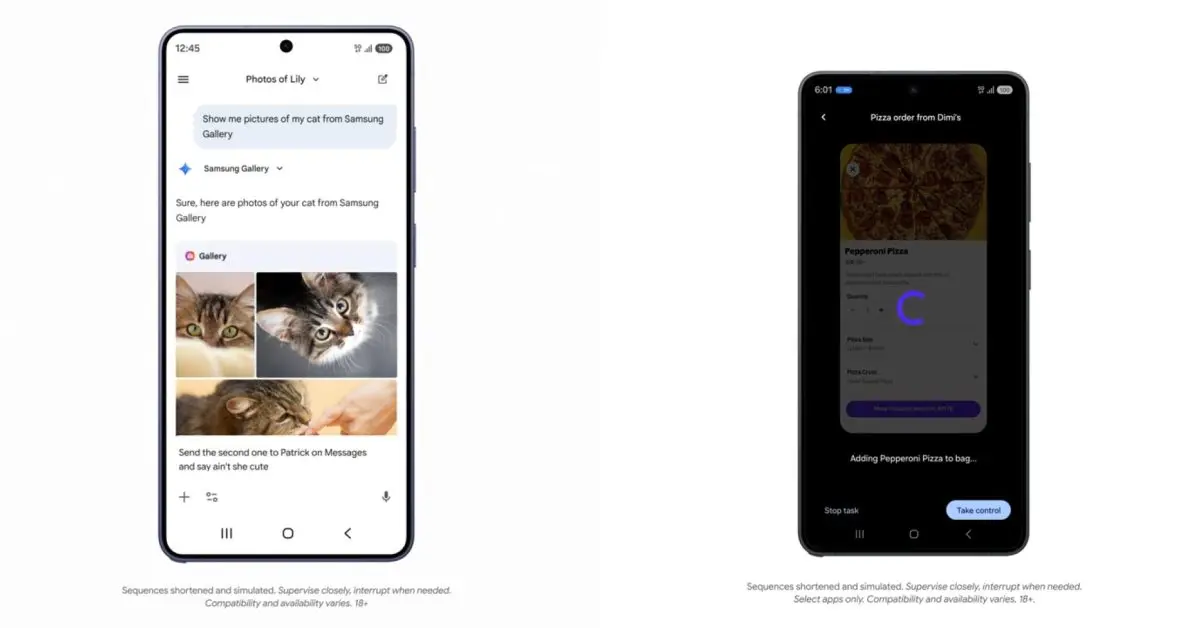

Samsung unveils Galaxy S26 lineup with Privacy Display tech and expanded AI capabilities

Technology

2

Anthropic refuses Pentagon's ultimatum over AI use in mass surveillance and autonomous weapons

Policy and Regulation

3

AI models deploy nuclear weapons in 95% of war games, raising alarm over military use

Science and Research