Google Announces Project Suncatcher: Ambitious Plan for AI Data Centers in Space

24 Sources

24 Sources

[1]

Meet Project Suncatcher, Google's plan to put AI data centers in space

The tech industry is on a tear, building data centers for AI as quickly as they can buy up the land. The sky-high energy costs and logistical headaches of managing all those data centers have prompted interest in space-based infrastructure. Moguls like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk have mused about putting GPUs in space, and now Google confirms it's working on its own version of the technology. The company's latest "moonshot" is known as Project Suncatcher, and if all goes as planned, Google hopes it will lead to scalable networks of orbiting TPUs. The space around earth has changed a lot in the last few years. A new generation of satellite constellations like Starlink has shown it's feasible to relay Internet communication via orbital systems. Deploying high-performance AI accelerators in space along similar lines would be a boon to the industry's never-ending build-out. Google notes that space may be "the best place to scale AI compute." Google's vision for scalable orbiting data centers relies on solar-powered satellites with free-space optical links connecting the nodes into a distributed network. Naturally, there are numerous engineering challenges to solve before Project Suncatcher is real. As a reference, Google points to the long road from its first moonshot self-driving cars 15 years ago to the Waymo vehicles that are almost fully autonomous today. Taking AI to space Some of the benefits are obvious. Google's vision for Suncatcher, as explained in a pre-print study (PDF), would place the satellites in a dawn-dusk sun-synchronous low-earth orbit. That ensures they would get almost constant sunlight exposure (hence the name). The cost of electricity on Earth is a problem for large data centers, and even moving them all to solar power wouldn't get the job done. Google notes solar panels are up to eight times more efficient in orbit than they are on the surface of Earth. Lots of uninterrupted sunlight at higher efficiency means more power for data processing. A major sticking point is how you can keep satellites connected at high speeds as they orbit. On Earth, the nodes in a data center communicate via blazing-fast optical interconnect chips. Maintaining high-speed communication among the orbiting servers will require wireless solutions that can operate at tens of terabits per second. Early testing on Earth has demonstrated bidirectional speeds up to 1.6 Tbps -- Google believes this can be scaled up over time. However, there is the problem of physics. Received power decreases with the square of distance, so Google notes the satellites would have to maintain proximity of a kilometer or less. That would require a tighter formation than any currently operational constellation, but it should be workable. Google has developed analytical models suggesting that satellites positioned several hundred meters apart would require only "modest station-keeping maneuvers." Hardware designed for space is expensive and often less capable compared to terrestrial systems because the former needs to be hardened against extreme temperatures and radiation. Google's approach to Project Suncatcher is to reuse the components used on Earth, which might not be very robust when you stuff them in a satellite. However, innovations like the Snapdragon-powered Mars Ingenuity helicopter have shown that off-the-shelf hardware may survive longer in space than we thought. Google says Suncatcher only works if TPUs can run for at least five years, which works out to 750 rad. The company is testing this by blasting its latest v6e Cloud TPU (Trillium) in a 67MeV proton beam. Google says while the memory was most vulnerable to damage, the experiments showed that TPUs can handle about three times as much radiation (almost 2 krad) before data corruption was detected. Google hopes to launch a pair of prototype satellites with TPUs by early 2027. It expects the launch cost of these first AI orbiters to be quite high. However, Google is planning for the mid-2030s when launch costs are projected to drop to as little as $200 per kilogram. At that level, space-based data centers could become as economical as the terrestrial versions. The fact is, terrestrial data centers are dirty, noisy, and ravenous for power and water. This has led many communities to oppose plans to build them near the places where people live and work. Putting them in space could solve everyone's problems (unless you're an astronomer).

[2]

Google has a 'moonshot' plan for AI data centers in space

Google has dreamed up a potential new way to get around resource constraints for energy-hungry AI data centers on Earth -- launching its AI chips into space on solar-powered satellites. It's a 'moonshot' research project Google announced today called Project Suncatcher. If it can ever get off the ground, the project would essentially create space-based data centers. Google hopes that by doing so, it can harness solar power around-the-clock. The dream is harnessing a near-unlimited source of clean energy that might allow the company to chase its AI ambitions without the concerns its data centers on Earth have raised when it comes to driving up power plant emissions and utility bills through soaring electricity demand.

[3]

Google exploring putting AI data centers in space -- Project Suncatcher wants to harness in-orbit solar power to scale AI compute

Solar power is much more efficient if there's no atmosphere in the way. Google just announced that it's exploring the idea of putting AI data centers into orbit to take advantage of the sun's solar output for power. According to Google Research, Project Suncatcher aims to have a constellation of solar-powered satellites with Google TPUs that communicate optically. This would allow the company to run a power-hungry data center without requiring the massive infrastructure needed to build one on land. Power is currently one of the bottlenecks of the AI infrastructure build-out, with companies like Microsoft sitting on GPU inventories because it doesn't have enough electricity for them. It's also causing electricity price hikes all over the U.S., burdening residents with the cost. Tech companies are investing in alternative technologies like small modular reactors and jet engines to solve their future power requirements, while current power supply challenges are quickly changing the makeup of power grids. Solar power is a clean source of energy that data centers can use for power, but it takes up a lot of space and is subject to the day-and-night cycle and atmospheric conditions. Google suggests that by putting its satellite in a dawn-dusk sun-synchronous low-earth orbit (meaning the satellite would orbit the earth's terminator, or the dividing line between day and night), it would be illuminated by the sun nearly 100% of the time. This would allow it to produce about eight times more power than ground-based solar panels, making space-based AI data centers potentially more scalable. While the initial study has proven the viability of the concept, Google says that it still has significant engineering challenges to overcome. Some of these include developing a wireless link between satellites that can support massive amounts of data, controlling a compact constellation of satellites so that they work in unison and avoid colliding with one another and other orbiting bodies, ensuring the radiation resistance of semiconductors in space, and managing the costs of launching the entire infrastructure into space. The company says that it plans to launch two prototypes in 2027 to test the system and check its viability for machine learning. Putting AI data centers might help reduce their impact on the electrical supply on Earth, but it also comes with its own set of issues. These include increasing the number of orbiting space junk around our planet and the possible disruption of ground-based astronomical observation, among others. The project is still in its early stages, though, so scientists and researchers have time to consider these things before launching a full-scale constellation in low-earth orbit.

[4]

Google Eyes Space-Based Data Centers With 'Project Suncatcher'

When he's not battling bugs and robots in Helldivers 2, Michael is reporting on AI, satellites, cybersecurity, PCs, and tech policy. Will the next space race feature tech giants rushing to deploy data centers in the sky? Google today announced an effort to launch satellites equipped with the company's AI chips -- something SpaceX CEO Elon Musk and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos are also pursuing. Google describes Project Suncatcher as a "research moonshot to one day scale machine learning in space." Like others, Google sees potential in harnessing the Sun to power a new class of data centers that orbit the Earth rather than consume energy here on Earth. Google will initially launch two prototype satellites in early 2027. Each one will be outfitted with the company's custom AI chips, called the Tensor Processing Unit, which are available through Google's ground-based data centers. "Our TPUs are headed to space!" CEO Sundar Pichai tweeted. Google is enlisting satellite company and imaging provider Planet Labs to help build the Suncatcher hardware. In the meantime, Pichai noted that his company has already simulated how the TPUs might perform in space. "Early research shows our Trillium-generation TPUs (our Tensor processing units, purpose-built for AI) survived without damage when tested in a particle accelerator to simulate low-Earth orbit levels of radiation," he wrote. The company published more details in a preprint paper and research post, which reveal that Google envisions potentially using "fleets of satellites equipped with solar arrays" to tap the Sun's energy in "near-constant sunlight." To rival the computing capabilities of Earth-based data centers, the satellites could transmit data to each other with the help of space-based lasers, which SpaceX's Starlink already supports. Google will need to overcome some major challenges, though, including "thermal management, high-bandwidth ground communications, and on-orbit system reliability," along with the costs. The paper largely sidesteps a major concern about orbiting data centers: The vacuum of space complicates cooling due to the absence of air to carry away heat. Google offers only a brief statement: "Cooling would be achieved through a thermal system of heat pipes and radiators while operating at nominal temperatures." Even so, the company's research paper concludes "in the long run [space-based data centers] may be the most scalable solution, with the additional benefit of minimizing the impact on terrestrial resources such as land and water." Google won't be alone in developing the technology. Musk tweeted last week about pursuing the same ambition, saying his company already has a foundation in Starlink, the satellite internet constellation. In addition, a startup called Starcloud successfully launched its first test satellite, outfitted with an Nvidia AI GPU, this past weekend, with the goal of developing its own network orbiting data centers. Meanwhile, Google's research paper notes it would need to rely on SpaceX, its future reusable rockets, and the lower launch costs to deploy its own orbiting data centers. "Our analysis of historical and projected launch pricing data suggests that with a sustained learning rate, prices may fall to less than $200/kg by the mid-2030s," the research post added. "At that price point, the cost of launching and operating a space-based data center could become roughly comparable to the reported energy costs of an equivalent terrestrial data center on a per-kilowatt/year basis."

[5]

Google launches AI hype to the moon with Project Suncatcher

Chocolate Factory's latest moonshot aims to put AI supercomputing cluster in sun-sychronous orbit Google on Tuesday announced a new moonshot - launching constellations of solar-powered satellites packed to the gills with its home-grown tensor processing units (TPUs) to form orbital AI datacenters. "In the future, space may be the best place to scale AI compute," Google executives wrote in a blog post, in which they explain that solar panels can be eight times more efficient in space than on Earth, and can produce power continuously. Availability of energy has become a limiting factor for terrestrial datacenter builds, so the prospect of an abundant source of clean uninterrupted energy is no doubt quite attractive. However, as Google points out, realizing this plan requires it to overcome significant challenges, one of which is finding enough rockets to place a useful amount of infrastructure in orbit. Despite SpaceX being on track to conduct over 140 launches this year, launch capacity is not easy to come by. Launch cost is another consideration. Assuming that launch prices fall to $200 per kilogram by the mid 2030s, Google contends that space-based datacenters will be roughly comparable to their terrestrial equivalents in terms of energy costs. Current launch prices are more than ten times Google's desired cost. AI infrastructure also needs fast and resilient networking, and vendors today provide that with optic fibers and/or copper wires. For Project Suncatcher, Google will instead transmit data wirelessly through the near vacuum of Earth orbit. By deploying spatial multiplexing, a technique for increasing throughput using multiple independent data streams, Google expects it will be able to connect large numbers of satellites together at "tens of terabits a second." Google says it's already shown that the technique can be effective using 800 Gbps optics, but admits those systems required a lot of energy. "Achieving this kind of bandwidth requires received power levels thousands of times higher than typical in conventional, long-range deployments," Google explained. "Since received power scales inversely with the square of the distance, we can overcome this challenge by flying the satellites in a very close formation - kilometers or less." In other words, these compute constellations will need to be quite dense. In one simulation, Google suggests a cluster of 81 satellites that fly between 100-200 meters from one another in an arrangement two kilometers across and at an altitude of 650 kilometers. If Google manages to get a sufficiently large fleet of TPUs into orbit and can make the space-based communications network reliable, the equipment still needs to survive the unforgiving environment of space. The source of energy that makes the idea of a space-based AI supercomputer so attractive also happens to spew out ionizing radiation, which isn't exactly great for electronics. On Earth, we're shielded from much of this radiation by the planet's electromagnetic field and thick atmosphere. However, in orbit, those protections are not nearly as strong. Google is already investigating radiation hardened versions of its TPUs. And, as it turns out, the company may not need to do much to keep them alive. In testing, Google exposed its TPU v6e (codenamed Trillium) accelerators to a 67 megaelectron-volt photon beam to see how it would cope with radiation. The results showed that the most sensitive piece of the accelerator was its high-bandwidth memory modules, which began showing irregularities after a cumulative dose of 2 krad(Si), which is almost 3 times what the chip would be expected to endure in a shielded environment over its five year mission. Google conducted system tests on Earth and documented those efforts in this prepublication paper [PDF]. The company plans to launch a pair of prototype satellites in 2027 to further evaluate its hardware and the feasibility of orbiting datacenters. Google isn't the first to suggest space as the next datacenter frontier. We reported on a startup that hoped to do it back in 2017 but that effort never made it into orbit. Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) has been working on spacefaring compute platforms for years now. Its first unit, Spaceborne, launched in 2017 and spent nearly two years aboard the ISS, but experienced failures in one of its four redundant PSUs, and nine out of its 20 SSDs. Axiom Space also launched a similar compute prototype to the ISS in August. Just last month Amazon founder and executive chair Jeff Bezos predicted that, within the next two decades, gigawatt-scale datacenters will fill the skies powered by a limitless stream of photons from the sun. And last Saturday, Elon Musk said SpaceX will build orbiting datacenters. ®

[6]

Google contemplates putting giant AI installations in low-earth orbit

Putting AI in space may sound like a sci-fi nightmare, but Google is thinking about the idea with a research endeavor called Project Suncatcher. The idea is to put power-hungry data centers into orbit on solar-powered satellites, so they can be powered by unlimited, clean energy available 24 hours a day. That would mitigate the nastiest aspects of AI cloud computing, like the use of power plants that spew huge amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. Project Suncatcher is a literal moonshot of the type that Google used to do more often. The search giant wants to put its AI chips, called Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), into orbit aboard solar panel-equipped satellites. "In the future, space may be the best place to scale AI compute," wrote Google senior director Travis Beals. "In the right orbit, a solar panel can be up to 8 times more productive than on Earth, and produce power nearly continuously, reducing the need for batteries." Suffice to say, the idea poses numerous challenges. That proximity to the sun would expose the TPUs to high levels of radiation that can rapidly degrade electronic components. However, Google has tested its current chips for radiation tolerance and said they'd be able to survive a five year mission without suffering permanent failures. Another challenge is the high-speed data links of "tens of terabits per second" and low latency required between satellites. Those speeds would be hard to achieve in space, as transmitting data at long distances requires exponentially more power than on Earth. To achieve that, Google said it may need to maneuver TPU-equipped satellites into tight formations, possibly within "kilometers or less" of each other. That would have the added benefit of reducing "station keeping" thrust maneuvers needed to keep the satellites in the right position. The determining factor, though, is money. Launching TPUs into space may not seem cost-efficient, but Google's analysis shows that doing so could be "roughly comparable" to data centers on Earth (in terms of power efficiency) by around the mid-2030s. While it's currently only a preliminary research paper, Google is planning to put Project Suncatcher through some initial trials. It has teamed with a company called Planet on a "learning mission" to launch a pair of prototype satellites into orbit by 2027. "This experiment will test how our models and TPU hardware operate in space and validate the use of optical inter-satellite links for distributed ML [machine learning] tasks," Google wrote.

[7]

Google plans orbital AI data centers powered directly by sunlight

Imagine data centers floating in orbit, powered directly by the Sun and running machine learning models beyond Earth's energy constraints. That's Google's bold new moonshot, Project Suncatcher, a research initiative exploring how constellations of solar-powered satellites could one day scale artificial intelligence (AI) computing in space. Announced this week, the project envisions compact networks of satellites equipped with Google's Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), interconnected through optical links, and powered by nearly continuous sunlight.

[8]

Google wants to build AI data centers in space using satellites

A network of solar-powered satellites orbiting the Earth could perform AI computing in the future. It's been hard to avoid tech giant Google's AI ventures lately. You might find all those new AI services and features useful, or you might find them annoying -- but either way, one thing is absolutely true: they run in data centers that suck down huge amounts of power. And, apparently, the data centers here on Earth aren't enough. Yesterday, Google announced Project Suncatcher and its intention to explore the possibility of running AI calculations in space. Project Suncatcher will investigate whether networks of solar-powered satellites equipped with Tensor AI chips could serve as data centers in space. In the blog post, Google mentions that there are several major challenges with the project, including that the satellites in the network will need to move in a much tighter formation than existing satellite networks, and that the Tensor chips will also need to cope with cosmic radiation while in orbit around the Earth. Two prototype satellites will be launched into orbit by early 2027, but Google says there's still a long way to go before the Project Suncatcher network can become operational. Google expects that launch costs will not be low enough to make the satellite network a cost-effective alternative to data centers on Earth for a long time -- at least until the mid-2030s.

[9]

Google's next moonshot is putting TPUs in space with 'Project Suncatcher'

Google is starting a new research moonshot called Project Suncatcher to "one day scale machine learning in space." This would involve Google Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) AI chips being placed onboard an interconnected network of satellites to "harness the full power of the Sun." Specifically, a "solar panel can be up to 8 times more productive than on earth" for near-continuous power using a "dawn-dusk sun-synchronous low earth orbit" that reduces the need for batteries and other power generation. In the future, space may be the best place to scale AI compute. These satellites would connect via free-space optical links, with large-scale ML workloads "distributing tasks across numerous accelerators with high-bandwidth, low-latency connections." To match data centers on Earth, the connection between satellites would have to be tens of terabits per second, and they'd have to fly in "very close formation (kilometers or less)." ...with satellites positioned just hundreds of meters apart, we will likely only require modest station-keeping maneuvers to maintain stable constellations within our desired sun-synchronous orbit. Google has already conducted radiation testing on TPUs (Trillium, v6e), with "promising" results: While the High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) subsystems were the most sensitive component, they only began showing irregularities after a cumulative dose of 2 krad(Si) -- nearly three times the expected (shielded) five year mission dose of 750 rad(Si). No hard failures were attributable to TID up to the maximum tested dose of 15 krad(Si) on a single chip, indicating that Trillium TPUs are surprisingly radiation-hard for space applications. Finally, Google believes that launch costs will "fall to less than $200/kg by the mid-2030s." At that point, the "cost of launching and operating a space-based data center could become roughly comparable to the reported energy costs of an equivalent terrestrial data center on a per-kilowatt/year basis." Our initial analysis shows that the core concepts of space-based ML compute are not precluded by fundamental physics or insurmountable economic barriers. Google still has to work through engineering challenges like thermal management, high-bandwidth ground communications, and on-orbit system reliability. It's partnering with Planet to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027 that test how "models and TPU hardware operate in space and validate the use of optical inter-satellite links for distributed ML tasks." More details are available in "Towards a future space-based, highly scalable AI infrastructure system design."

[10]

Orbiting AI data centers could become reality following Google's tests

Bench tests achieved 1.6 terabits per second between transceivers in controlled conditions Google's "Project Suncatcher" introduces an ambitious idea: to place fully functional AI data centers in orbit. These orbital platforms would consist of a constellation of compact satellites operating in a dawn-dusk sun-synchronous low Earth orbit, designed to capture near-continuous sunlight. Each unit would house machine learning hardware, including TPUs, powered by solar energy collected more efficiently than on Earth. The configuration aims to reduce dependency on heavy energy storage and to test whether computation beyond Earth's atmosphere can be both scalable and sustainable. The research team proposes inter-satellite communication at bandwidths comparable to ground-based data centers. Using multi-channel dense wavelength-division multiplexing and spatial multiplexing, the satellites could theoretically achieve tens of terabits per second. To close the signal power gap, the satellites would fly within just hundreds of meters of each other, enabling data transfer rates that a bench-scale test has already demonstrated at 1.6 Tbps. Maintaining such close formations, however, requires complex orbital control, modeled using Hill-Clohessy-Wiltshire equations and refined numerical simulations to counter gravitational and atmospheric effects. According to Google, its Trillium Cloud TPU v6e under 67 MeV proton exposure revealed no critical damage even at doses far exceeding expected orbital levels. The most sensitive components, high-bandwidth memory subsystems, showed only minor irregularities. This finding suggest existing TPU architectures could, with limited modification, endure low-Earth orbit conditions for extended missions. However, economic viability remains uncertain, though projected reductions in launch costs may make deployment plausible. If prices fall below $200 per kilogram by the mid-2030s, the expense of launching and maintaining space-based data centers could approach parity with terrestrial facilities when measured per kilowatt-year. Yet this assumes long-term reliability and minimal servicing requirements, both of which remain untested at scale. Despite the promising signals, many aspects of Project Suncatcher rest on theoretical modeling rather than field validation. The upcoming partnership with Planet, set to deploy two prototype satellites by 2027, will test optical interlinks and TPU performance under real orbital conditions. Whether these orbiting facilities can transition from research experiment to operational infrastructure depends on sustained advances in energy management, communication stability, and cost efficiency.

[11]

Google plans to put datacentres in space to meet demand for AI

US technology company's engineers want to exploit solar power and the falling cost of rocket launches Google is hatching plans to put artificial intelligence datacentres into space, with its first trial equipment sent into orbit in early 2027. Its scientists and engineers believe tightly packed constellations of about 80 solar-powered satellites could be arranged in orbit about 400 miles above the Earth's surface equipped with the powerful processors required to meet rising demand for AI. Prices of space launches are falling so quickly that by the middle of the 2030s the running costs of a space-based datacentre could be comparable to one on Earth, according to Google research released on Tuesday. Using satellites could also minimise the impact on the land and water resources needed to cool existing datacentres. Once in orbit, the datacentres would be powered by solar panels that can be up to eight times more productive than those on Earth. However, launching a single rocket into space emits hundreds of tonnes of CO. Objections could be raised by astronomers concerned that rising numbers of satellites in low orbit are "like bugs on a windshield" when they are trying to peer into the universe. The orbiting datacentres envisaged under Project Suncatcher would beam their results back through optical links, which typically use light or laser beams to transmit information. Major technology companies pursuing rapid advances in AI are projected to spend $3tn (£2.3tn) on earthbound datacentres from India to Texas and from Lincolnshire to Brazil. The spending has fueled rising concern about the impact on carbon emissions if clean energy is not found to power the sites. "In the future, space may be the best place to scale AI computers," Google said. "Working backward from there, our new research moonshot, Project Suncatcher, envisions compact constellations of solar-powered satellites, carrying Google TPUs and connected by free-space optical links. This approach would have tremendous potential for scale, and also minimises impact on terrestrial resources." TPUs are processors optimised for training and the day-to-day use of AI models. Free-space optical links deliver wireless transmission. Elon Musk, who runs the Starlink satellite internet provider and the SpaceX rocket programme, last week said his companies would start scaling up to create datacentres in space. Nvidia AI chips will also be launched into space later this month in partnership with the startup Starcloud. "In space, you get almost unlimited, low-cost renewable energy," said Philip Johnston, co-founder of the startup. "The only cost on the environment will be on the launch, then there will be 10 times carbon dioxide savings over the life of the datacentre compared with powering the datacentre terrestrially." Google is planning to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027 and said its research results were a "first milestone towards a scalable space-based AI". But it sounded a cautionary note: "Significant engineering challenges remain, such as thermal management, high-bandwidth ground communications and on-orbit system reliability."

[12]

Eyes turn to space to feed power-hungry data centers

Tech firms are floating the idea of building data centers in space and tapping into the sun's energy to meet out-of-this-world power demands in a fierce artificial intelligence race. US startup Starcloud this week sent a refrigerator-sized satellite containing an Nvidia graphics processing unit (GPU) into orbit in what the AI chip maker touted as a "cosmic debut" for the mini-data center. "The idea is that it will soon make much more sense to build data centers in space than it does to build them on Earth," Starcloud chief executive Philip Johnston said at a recent tech conference in Riyadh. Along with a constant supply of solar energy, data centers are easier to cool in space, advocates note. Announcements have come thick and fast, the latest being Google this week unveiling plans to launch test satellites by early 2027 as part of its Suncatcher project. That news came just days after tech billionaire Elon Musk claimed his SpaceX startup should be capable of deploying data centers in orbit next year thanks to its Starlink satellite program. Starcloud's satellite was taken into space by a SpaceX rocket on Sunday. Junk and radiation Current projects to put data centers into orbit envision relying on clusters of low Earth orbit satellites positioned close enough together to ensure reliable wireless connectivity. Lasers will connect space computers to terrestrial systems. "From a proof concept, it's already there," University of Arizona engineering professor Krishna Muralidharan, who is involved with such work, said of the technology. Muralidharan believes space data centers could be commercially viable in about a decade. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, the tech titan behind private space exploration company Blue Origin, has estimated it might take up to twice that long. Critical technical aspects of such operations need to be resolved, particularly harm done to GPUs by high levels of radiation and extreme temperatures as well as the danger of being hit by space junk. "Engineering work will be necessary," said University of Michigan assistant professor of engineering Christopher Limbach, contending that it is a matter of cost rather than technical feasibility. Sun synced The big draw of space for data centers is power supply, with the option of synchronizing satellites to the sun's orbit to ensure constant light on solar panels. Tech titans building AI data centers have ever growing need for electricity, and have even taken to investing in nuclear power plants. Data centers in space also avoid the challenges of acquiring land and meeting local regulations or community resistance to projects. And advocates argue that data centers operating in space are less harmful overall to the environment, aside from the pollution generated by rocket launches. Water needed to cool a space data center would be about the same amount used by a space station, relying on exhaust radiators and re-using a relatively small amount of liquid. "The real question is whether the idea is economically viable," said Limbach. An obstacle to deploying servers in space has been the cost of getting them into orbit. But a reusable SpaceX mega-rocket called Starship with massive payload potential promises to slash launch expenses by at least 30 times. "Historically, high launch costs have been a primary barrier to large-scale space-based systems," Suncatcher project head Travis Beals said in a post. But project launch pricing data suggests prices may fall by the mid-2030s to the point at which "operating a space-based data center could become comparable" to having it on Earth, Beals added. "If there ever was a time to chart new economic paths in space -- or re-invent old ones -- it is now," Limbach said.

[13]

Meet Project Suncatcher, a research moonshot to scale machine learning compute in space.

Artificial intelligence is a foundational technology that could help us tackle humanity's greatest challenges. Now, we're asking where we can go next to unlock its fullest potential. Today we're announcing Project Suncatcher, our new research moonshot to one day scale machine learning in space. Working backward from this potential future, we're exploring how an interconnected network of solar-powered satellites, equipped with our Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) AI chips, could harness the full power of the Sun. Inspired by other Google moonshots like autonomous vehicles and quantum computing, we've begun work on the foundational work needed to one day make this future possible. We're excited that this is a growing area of exploration, and our initial research, shared today in a preprint paper, describes our approach to satellite constellation design, control, and communication, and also our initial learnings from radiation testing Google TPUs. Our next step is a learning mission in partnership with Planet to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027 that will test our hardware in orbit, laying the groundwork for a future era of massively-scaled computation in space.

[14]

Eyes turn to space to feed power-hungry data centers

New York (AFP) - Tech firms are floating the idea of building data centers in space and tapping into the sun's energy to meet out-of-this-world power demands in a fierce artificial intelligence race. US startup Starcloud this week sent a refrigerator-sized satellite containing an Nvidia graphics processing unit (GPU) into orbit in what the AI chip maker touted as a "cosmic debut" for the mini-data center. "The idea is that it will soon make much more sense to build data centers in space than it does to build them on Earth," Starcloud chief executive Philip Johnston said at a recent tech conference in Riyadh. Along with a constant supply of solar energy, data centers are easier to cool in space, advocates note. Announcements have come thick and fast, the latest being Google this week unveiling plans to launch test satellites by early 2027 as part of its Suncatcher project. That news came just days after tech billionaire Elon Musk claimed his SpaceX startup should be capable of deploying data centers in orbit next year thanks to its Starlink satellite program. Starcloud's satellite was taken into space by a SpaceX rocket on Sunday. Junk and radiation Current projects to put data centers into orbit envision relying on clusters of low Earth orbit satellites positioned close enough together to ensure reliable wireless connectivity. Lasers will connect space computers to terrestrial systems. "From a proof concept, it's already there," University of Arizona engineering professor Krishna Muralidharan, who is involved with such work, said of the technology. Muralidharan believes space data centers could be commercially viable in about a decade. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, the tech titan behind private space exploration company Blue Origin, has estimated it might take up to twice that long. Critical technical aspects of such operations need to be resolved, particularly harm done to GPUs by high levels of radiation and extreme temperatures as well as the danger of being hit by space junk. "Engineering work will be necessary," said University of Michigan assistant professor of engineering Christopher Limbach, contending that it is a matter of cost rather than technical feasibility. Sun synched The big draw of space for data centers is power supply, with the option of synchronizing satellites to the sun's orbit to ensure constant light on solar panels. Tech titans building AI data centers have ever-growing need for electricity, and have even taken to investing in nuclear power plants. Data centers in space also avoid the challenges of acquiring land and meeting local regulations or community resistance to projects. And advocates argue that data centers operating in space are less harmful overall to the environment, aside from the pollution generated by rocket launches. Water needed to cool a space data center would be about the same amount used by a space station, relying on exhaust radiators and re-using a relatively small amount of liquid. "The real question is whether the idea is economically viable," said Limbach. An obstacle to deploying servers in space has been the cost of getting them into orbit. But a reusable SpaceX mega-rocket called Starship with massive payload potential promises to slash launch expenses by at least 30 times. "Historically, high launch costs have been a primary barrier to large-scale space-based systems," Suncatcher project head Travis Beals said in a post. But project launch pricing data suggests prices may fall by the mid-2030s to the point at which "operating a space-based data center could become comparable" to having it on Earth, Beals added. "If there ever was a time to chart new economic paths in space -- or re-invent old ones -- it is now," Limbach said.

[15]

Google to launch TPU-equipped satellites in 2027 - SiliconANGLE

Google LLC today detailed Project Suncatcher, an initiative to launch artificial intelligence chips into orbit aboard satellites. One of the main motivations behind the project is that solar panels generate significantly more power in space than on Earth. Moreover, there's no need for batteries. On Earth, batteries provide a backup power source when a solar panel can't generate electricity, for example at nighttime or during rainfall. Google believes that the efficiencies provided by space-based solar panels could eventually offset the cost of launching chips to space. "The cost of launching and operating a space-based data center could become roughly comparable to the reported energy costs of an equivalent terrestrial data center on a per-kilowatt/year basis," Travis Beals, the senior director of Google's Paradigms of Intelligence research unit, explained in a blog post. One of the challenges involved in operating orbital AI clusters stems from the fact that language models often run across multiple graphics cards. Those graphics cards, in turn, must coordinate their work. That means graphics cards installed in different satellites need a way to exchange data with one another. Google plans to sync information between satellites using a technology called FSO, or free-space optical communication. FSO encodes network traffic into laser beams. The challenge is that Google's proposed FSO implementation would have to beam data at a rate of tens of terabits per second. Under normal circumstances, providing such bandwidth would require thousands of times more power than current FSO implementations. Google proposes to lower power requirements by deploying its satellites close to one another. The shorter the distance between two satellites, the less power is needed for data transmission. But while that arrangement addresses one technical challenge, it creates a new one. Satellites deployed in close proximity to one another must be prevented from colliding with their neighbors or straying off course. Google developed a set of physics algorithms to understand how a dense satellite constellation would operate. It determined that the challenges such a configuration presents are manageable. "The models show that, with satellites positioned just hundreds of meters apart, we will likely only require modest station-keeping maneuvers to maintain stable constellations within our desired sun-synchronous orbit," Beals wrote. Google also studied whether AI chips can withstand the radiation to which they would be exposed in space. The evaluation focused on Trillium, the latest iteration of the company's TPU machine learning accelerator series. Google determined that even Trillium's most sensitive component, its HBM memory, could operate for years in orbit.

[16]

Google Is Sending Its TPUs to Space to Build Solar-Powered Data Centres | AIM

Google has announced a new research initiative, Project Suncatcher, which aims to explore the feasibility of scaling artificial intelligence (AI) compute in space using solar-powered satellite constellations equipped with Tensor Processing Units (TPUs). "Inspired by our history of moonshots, from quantum computing to autonomous driving, Project Suncatcher is exploring how we could one day build scalable ML compute systems in space, harnessing more of the sun's power (which emits more power than 100 trillion times humanity's total electricity production)," said Google CEO Sundar Pichai, in a post on X. ' The project, led by Travis Beals, senior director of Paradigms of Intelligence at Google, proposes a system where solar-powered satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) perform machine learning (ML) workloads while communicating through free-space optical links. "Space may be the best place to scale AI compute," Beals said in a statement. "In the right orbit, a solar panel can be up to 8 times more productive than on Earth, and produce power nearly continuously, reducing the need for batteries." According to a preprint paper released alongside the announcement -- Towards a future space-based, highly scalable AI infrastructure system design -- the initiative focuses on building modular, interconnected satellite networks that can function like data centres in orbit. The proposed system would operate in a dawn-dusk sun-synchronous orbit, ensuring near-constant exposure to sunlight and reducing reliance on heavy batteries. To achieve data centre-level performance, the satellites would need to support inter-satellite links capable of tens of terabits per second. Google's researchers said they have already achieved 1.6 terabits per second transmission in lab conditions using a single optical transceiver pair. Achieving such bandwidth in orbit requires satellites to fly in close formations, just a few hundred meters apart. "With satellites positioned this closely, only modest station-keeping manoeuvres would be needed to maintain stability," the paper noted. Radiation tolerance was another major focus. Tests conducted on Google's Trillium v6e Cloud TPU chips under a 67 MeV proton beam showed that the chips could withstand nearly three times the expected five-year mission radiation dose without failure. Historically, launch costs have made large-scale space infrastructure unviable. However, Google's analysis suggests that if launch costs fall below $200 per kilogram -- as projected by the mid-2030s -- operating a space-based AI system could be cost-competitive with terrestrial data centres. The company's next milestone is a partnership with Planet Labs to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027. The mission will test TPU performance in orbit and evaluate optical inter-satellite links for distributed ML tasks. "Our initial analysis shows that the core concepts of space-based ML compute are not precluded by fundamental physics or insurmountable economic barriers," Beals said. "Significant engineering challenges remain, such as thermal management, high-bandwidth ground communications, and on-orbit system reliability."

[17]

A startup backed by Nvidia wants to build AI data centers in space

The company argues that space offers cheaper energy and cooling compared to Earth's resource-hungry data centers. Starcloud plans a November launch of an Nvidia H100 GPU into orbit to test its functionality, aiming for extraterrestrial data centers as an alternative to Earth-based facilities. Datacenters on Earth require significant electricity and water for cooling. Starcloud posits that space offers more accessible and cheaper energy and cooling. The startup's white paper states that concept designs have not revealed "any insurmountable obstacles," but economic viability relies on decreasing space launch costs. Starcloud intends to create modular data centers in space. A 5GW data center would use a four-square-kilometer solar panel array and a heat-dissipating radiator array approximately half that size. Orbital data centers could expedite satellite data processing and support AI companies in managing compute demands for model training. These data centers would comprise individual modules. Upon reaching their end-of-life, these modules could be salvaged for material reuse or allowed to burn up in Earth's atmosphere, according to the white paper. Tech companies are expanding AI infrastructure, yet new Earth-based data centers consume vast resources. Companies like Meta face concerns from local communities regarding water supply and increased electricity use. In Memphis, xAI uses gas turbines to power data centers due to grid limitations, raising resident health concerns over emissions. Despite ecological and humanitarian impacts, AI companies heavily invest in complex AI models. Nvidia is a significant investor, providing OpenAI over $100 billion and backing startups addressing data center issues, including Starcloud. Starcloud's planned November satellite launch, containing an Nvidia GPU, is a preliminary step. Nvidia states this chip is one hundred times more powerful than previous space operations. Significant hurdles remain before Starcloud builds an extraterrestrial data center. The startup acknowledges regulatory challenges, particularly regarding increased collision risk to other satellites. The Union of Concerned Scientists reports over 7,500 active satellites currently in orbit. Launch costs present another hurdle. Starcloud expects launch costs to decrease and frequency to increase over the next decade. A 5GW data center would require approximately 100 launches for GPUs and another 100 for solar panel and radiator arrays. Starcloud CEO Philip Johnston predicts that "in ten years, nearly all new data centers will be being built in outer space."

[18]

Google aims for the stars - literally - with new 'moonshot' project

TL;DR: Google's Project Suncatcher aims to develop space-based data centers to leverage unlimited solar energy and the vacuum of space as a natural heatsink, reducing energy costs significantly. Overcoming challenges like high-speed satellite connections and radiation-hardened hardware is key to scaling AI compute off Earth. Google is joining in on the recent push to get data centers off Earth and into orbit in an effort to harness the endless solar energy of the Sun. It was only recently that NVIDIA announced that a company called Starcloud is sending NVIDIA's AI GPUs to space, marking a moment in history when it comes to space-based compute, as the Starcloud-1 satellite offers 100x more GPU compute than any previous space-based operation. Why are companies looking to space for data centers? There are a few simple reasons. The vacuum of space acts as an infinite heatsink, and the solar energy produced by the Sun is endless and free. Just those two facts combined mean energy costs in space will be 10x cheaper than land-based operations, even when including the cost to launch the data center, according to Starcloud. Google has now recognized the potential of space-based data centers with its announcement of a "moonshot" research project called "Project Suncatcher". "In the future, space may be the best place to scale AI compute," Travis Beals, a Google senior director for Paradigms of Intelligence As with anything that has yet to be done at scale, Project Suncatcher has a few hurdles that will need to be overcome first. One is the connection between satellites needing to "support tens of terabits per second" in order to provide a connection speed that is comparable to data centers on land, and hardware being able to withstand higher levels of radiation in space. According to the company, it has already tested Trillium Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) for radiation tolerance and found they can "survive a total ionizing dose equivalent to a 5-year mission life without permanent failures."

[19]

Google plans orbital AI data centers powered by the sun

Project Suncatcher explores using space-based solar energy to run AI workloads, reducing emissions and energy costs from Earth's data centers. Google announced Project Suncatcher, a research initiative to launch AI chips into space aboard solar-powered satellites, aiming to establish orbital data centers that utilize continuous solar energy to address terrestrial data center energy demands and emissions. The project represents Google's effort to overcome limitations in powering AI infrastructure on Earth. Traditional data centers consume substantial electricity, contributing to increased power-plant emissions and elevated utility costs. By relocating components to space, Google seeks to tap into solar power available nearly around the clock. Satellites in orbit avoid nighttime interruptions and atmospheric interference, enabling more consistent energy generation. This approach aligns with the company's broader AI development goals, where computational demands continue to escalate. Details of the project appear in a preprint paper released by Google, which outlines initial advancements without peer review. The paper, along with a blog post, emphasizes the potential of space for expanding AI capabilities. Travis Beals, senior director for Paradigms of Intelligence at Google, stated in the blog post, "In the future, space may be the best place to scale AI compute." This sentiment echoes in the preprint, reinforcing the project's focus on orbital computing. Central to Project Suncatcher are Google's Tensor Processing Units, or TPUs, designed for AI workloads. These units would orbit Earth on satellites equipped with solar panels. The panels in space generate electricity almost continuously, achieving productivity levels eight times higher than equivalent panels on the ground. This efficiency stems from uninterrupted sunlight exposure above the atmosphere, free from weather variations or day-night cycles that limit terrestrial solar installations. Communication between satellites poses a significant technical obstacle. To rival ground-based data centers, inter-satellite links must support data transfer rates of tens of terabits per second. Achieving such bandwidth requires precise coordination, with satellites positioned in formations mere kilometers or less apart. Current satellite operations maintain greater distances, so this proximity demands advanced maneuvering capabilities. Google identifies this closeness as essential for high-speed data exchange in a constellation network. The tighter formations also introduce risks from space debris. Existing orbital junk from past collisions already threatens active satellites. Closer groupings amplify collision probabilities, necessitating robust collision avoidance systems and ongoing orbital debris monitoring. Google acknowledges these challenges as critical to the project's feasibility, requiring innovations in satellite design and trajectory control. Radiation exposure in space presents another hurdle for electronic components. Unlike Earth environments, orbits subject hardware to intense cosmic and solar radiation, which can degrade performance. Google conducted tests on its latest Trillium TPUs to assess durability. Results show the units endure a total ionizing dose comparable to five years in orbit without experiencing permanent failures. These evaluations confirm the TPUs' resilience under simulated space conditions, supporting their use in long-duration missions. Launch and operational expenses currently make space-based systems cost-prohibitive. However, Google's analysis projects cost reductions over time. By the mid-2030s, expenses for launching and maintaining a space data center should align closely with energy costs for a comparable Earth facility, measured on a per-kilowatt-year basis. Factors include declining launch prices and improved satellite manufacturing efficiencies. To advance the initiative, Google collaborates with Planet, an Earth observation company. The partners plan a joint mission to deploy prototype satellites by 2027. This test will evaluate hardware performance in actual orbital conditions, gathering data on power generation, communication, and radiation effects to refine future implementations.

[20]

Google to test building AI data centres in space

Google plans to launch AI data centers into space by 2027. These solar-powered satellites will use proprietary AI chips. The project aims to leverage constant sunlight and vacuum cooling for efficiency. This initiative pushes Google's deeptech research boundaries. Other companies like SpaceX are also exploring similar space-based computing. "Our TPUs are headed to space," wrote Sudar Pichai, chief executive of Alphabet Inc, Google's parent, while launching Project Suncatcher -- an experiment to run artificial intelligence data centres in space. Google is launching two solar-powered satellites early 2027, each carrying four tensor processing units (TPUs) -- the company's proprietary AI chips which could run AI model training using power directly from the Sun. The project is part of Google's Moonshot philosophy, a radical idea which pushes the boundaries of space and engineering and often takes decades. For instance, Google envisioned autonomous vehicles 15 years ago which eventually became Waymo and has today completed 10 million trips without a single hazard. Similarly, a space-based data centre could be a reality by 2030. The advantages are radical -- constant sunlight, minimal atmospheric loss, no nightfall and vacuum-based cooling that could cut energy costs by up to 40% versus Earth-based data centres, the company said in a blog on Wednesday. In the right orbit, solar panels could be up to eight times more productive than on Earth, long durations of sunlight remove the need for heavy batteries, and cooling in space could significantly reduce energy and infrastructure costs. Google's math suggests that by 2030, the cost per kilowatt-year of operating space-based AI infrastructure could match that of terrestrial facilities. After major technology breakthroughs in quantum computing and autonomous driving, Google is now headed for off-planet computing, cementing its position as a deeptech research powerhouse. Google brought home seven Nobel Prizes and surpassed IBM in 2025 to become the No.2 company housing Nobel laureates, behind Bell Labs. However, there are major engineering hurdles to overcome. These include building ultra-fast optical links to connect satellites at terabit-per-second speeds, maintaining precise formations with satellites flying just hundreds of meters apart, and ensuring that compute hardware like TPUs can survive harsh space conditions and radiation over multi-year missions. Google plans to begin with a "learning mission" in cooperation with commercial partner Planet Labs, launching two prototype satellites early in 2027 to validate the hardware and optical communication systems in orbit. The vision is shared by billionaire Elon Musk who stated that his company, SpaceX, and their next-gen V3 Starlink satellites could serve as a foundation for space-based data centres. Other startups like Starcloud, Axiom Space and Lonestar Data Holdings are also working in this direction.

[21]

'Great Idea Lol,' Says Elon Musk As Sundar Pichai Reveals Plan To Launch Google's AI Data Center Into Space - Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG), Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

A lighthearted exchange between Alphabet Inc. (NASDAQ:GOOG) (NASDAQ:GOOGL) CEO Sundar Pichai and SpaceX chief Elon Musk followed Google's bold new plan to build the world's first AI data center in space. Google's Project Suncatcher Takes AI Beyond Earth On Tuesday, in a post on X, formerly Twitter, Pichai unveiled Project Suncatcher, an initiative to establish an AI data center in low Earth orbit powered directly by the sun. "Our TPUs are headed to space!" Pichai quipped, referring to Google's Tensor Processing Units -- custom-built chips that drive the company's machine learning models. He explained that the project aims to explore "how we could one day build scalable ML compute systems in space, harnessing more of the sun's power." According to Pichai, early testing showed Google's Trillium-generation TPUs survived radiation levels comparable to those found in orbit. The company plans to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027 in collaboration with Planet Labs, marking the next milestone in its pursuit of zero-carbon, solar-powered AI infrastructure. See Also: Tim Cook Says US-Made Servers Will Power Apple Intelligence, Meeting $600 Billion Manufacturing Commitment Amid Trump's Build-At-Home Push Massive Challenges, But Big Ambitions While calling the effort a "moonshot," Pichai acknowledged major technical hurdles ahead, including thermal management and on-orbit reliability. He said further breakthroughs will be needed before such space-based compute systems can operate at scale. Elon Musk Joins The Conversation Shortly after Pichai's post, Musk chimed in with a brief but viral reply: "Great idea lol." Pichai responded in kind, adding, "Only possible because of SpaceX's massive advances in launch technology!" -- a nod to SpaceX's reusable rockets that have drastically reduced the cost of reaching orbit. According to Benzinga's Edge Stock Rankings, GOOGL ranks in the 90th percentile for Momentum, underscoring its strong long-term price performance. Click here to see how it stacks up against its peers. Read Next: Trump Turnberry Is 'Our Monalisa' Says Eric Trump As He Shrugs Off Millions In Losses -- 'We Don't Give A...' Disclaimer: This content was partially produced with the help of AI tools and was reviewed and published by Benzinga editors. Photo courtesy: Shutterstock GOOGAlphabet Inc$275.75-2.95%OverviewGOOGLAlphabet Inc$275.25-2.99%Market News and Data brought to you by Benzinga APIs

[22]

Google unveils 2027 plan: Launch solar-powered AI data centres into space - here's how it'll work

Google AI data centres in space: Google is planning to launch AI datacenters into space with solar-powered satellites by early 2027, aiming to address the growing demand for AI computing power. This initiative, Project Suncatcher, could offer cost-effective and environmentally beneficial solutions compared to terrestrial facilities, though it raises concerns about space debris and astronomical interference. Google AI data centres in space: Google is exploring a bold new frontier for artificial intelligence, planning to send AI datacentres into space, with its first trial satellites expected to launch in early 2027. The initiative, dubbed Project Suncatcher, aims to place tightly packed constellations of around 80 solar-powered satellites about 400 miles above Earth, each carrying powerful processors designed to handle the growing demand for AI, as per a report. According to Google research released on Tuesday, falling launch costs could make space-based datacentres as cost-effective as those on Earth by the mid-2030s. In addition to scaling computing power, moving datacentres into orbit could reduce the strain on land and water resources used to cool terrestrial facilities. ALSO READ: 300 million at risk: Goldman Sachs lists top jobs that AI can replace, but plumbers and electricians may get rich Once in orbit, the satellites would be powered by highly efficient solar panels, up to eight times more productive than panels on Earth, as per The Guardian. Data would be transmitted back to the ground using optical links, which rely on light or laser beams. However, the plan raises environmental and astronomical concerns. Launching a single rocket emits hundreds of tonnes of CO2, and astronomers have warned that large numbers of satellites in low orbit could interfere with observations, comparing them to "bugs on a windshield," as per The Guardian report. ALSO READ: Liquidity panic? SOFR-IORB spread hits highest level since 2020 -- QE next? The initiative comes as major tech companies are projected to spend $3 trillion on Earth-based datacentres worldwide, from India to Texas and Lincolnshire to Brazil, sparking concerns over carbon emissions unless clean energy sources are used, as per the report. Philip Johnston, co-founder of startup Starcloud, which is partnering with Nvidia to launch AI chips into space later this month, highlighted the potential environmental benefits, saying, "In space, you get almost unlimited, low-cost renewable energy," adding, "The only cost on the environment will be on the launch, then there will be 10 times carbon dioxide savings over the life of the datacentre compared with powering the datacentre terrestrially," as quoted by The Guardian. ALSO READ: Why US market is down today? Key points investors need to take note as Dow, S&P 500 and Nasdaq fall Google plans to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027, calling the effort a "first milestone towards a scalable space-based AI," as per the report. However, the tech giant cautioned that, "Significant engineering challenges remain, such as thermal management, high-bandwidth ground communications and on-orbit system reliability," as quoted by The Guardian. ALSO READ: BTC crash alert: Why Bitcoin price dropped to $107,000 and why experts warn it could fall to $88,000 What is Google's Project Suncatcher? Google's plan to put AI datacentres into space using solar-powered satellites. Will space datacentres become cheaper than Earth-based ones? Yes, falling launch costs could make them comparable by the mid-2030s.

[23]

Project Suncatcher: Google's crazy plan to host an AI datacenter in space explained

Google tests satellite-linked TPUs to run machine learning in space When Google calls something a "moonshot," it's rarely just a metaphor. Its latest experiment - Project Suncatcher - quite literally looks beyond Earth. Google has outlined an idea that sounds like it's ripped from a sci-fi screenplay: building a space-based AI infrastructure, powered entirely by sunlight, and interconnected through high-speed optical links. At its core, Project Suncatcher is an attempt to reimagine where AI gets trained. Today's machine learning models, from Gemini to ChatGPT to Deepseek, demand staggering amounts of energy and compute power. The world's data centers already consume more electricity than entire countries. Google's pitch is bold - if sunlight is the limiting factor on Earth, why not go where it never sets? Also read: Google wants to take AI to space with solar-powered data centres Google's engineers envision a constellation of satellites, each equipped with solar panels and Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) - the custom chips that power many of the company's AI systems. Instead of relying on Earth's power grids, these orbiting machines would draw nearly continuous solar energy in what's called a sun-synchronous orbit, a path that keeps the satellites perpetually in daylight. These satellites would then link together using free-space optical communication, essentially lasers transmitting data between satellites at terabit speeds. If you imagine fiber-optic cables stretched across space without the cables, you're not far off. Google says a lab demo has already achieved 800 Gbps each way, proving the physics works - at least in controlled conditions. The result? A "data center" that lives in orbit, where energy is free, cooling is minimal, and sunlight never fades. The immediate appeal is energy efficiency. In orbit, solar panels can generate up to eight times more power than on Earth, thanks to constant sunlight and no atmospheric interference. That could mean cleaner, cheaper, and more scalable compute without overloading terrestrial grids. Then there's the environmental argument. As AI systems scale, their energy needs balloon. Google's researchers suggest that space-based infrastructure could reduce the strain on Earth's limited power supply while taking advantage of what is effectively limitless solar energy. Finally, there's the scalability factor. Launch costs have plummeted, from tens of thousands of dollars per kilogram a decade ago to around $1,000 today, and are expected to fall further. Google estimates that once costs hit $200/kg, space computing could rival the cost-efficiency of terrestrial data centers. Of course, it's one thing to imagine a "solar-powered AI cloud" in orbit, it's entirely another to build one. Also read: Amazon threatens Perplexity with legal action over AI agentic shopping For starters, keeping a tight formation of satellites flying just hundreds of meters apart in low Earth orbit is a massive challenge. Engineers model these formations using advanced orbital dynamics equations to prevent drift, collision, and interference. Google's prototype simulations show an 81-satellite cluster maintaining formation within a one-kilometer radius. Then comes the radiation problem. Space is brutal on electronics - cosmic rays can fry delicate chips. Google tested its Trillium TPU v6e under a 67 MeV proton beam and found no catastrophic failures even at 15 krad of radiation, suggesting the chips might survive long-term exposure. Still, long-duration reliability remains unproven. Thermal management, debris avoidance, and maintenance are other obstacles. There's no technician to swap a failed chip when your data center is 650 kilometers above Earth. If it works, the implications could be profound. Imagine a future where the Earth's heaviest AI workloads - massive model training, climate simulations, or satellite imaging analysis - happen entirely in orbit, powered by the same sun that fuels life below. It also raises fascinating questions about data sovereignty and infrastructure ethics. Who owns computation that happens outside any nation's borders? Could orbital AI systems change the geopolitics of data control? Google hasn't addressed these yet, but they'll matter if Project Suncatcher ever gets off the ground. Right now, this is just a research concept, a thought experiment made real by prototypes and math. But it signals something larger: the boundaries of AI infrastructure are expanding, literally beyond Earth. As AI pushes against the limits of compute, power, and sustainability, companies like Google are forced to look up and not just forward. If the cloud was the 2010s' defining tech metaphor, Project Suncatcher hints at what comes next. The sky isn't the limit. It's the datacenter.

[24]

Google wants to take AI to space with solar-powered data centres

Google plans to launch two prototype satellites with Planet Labs by 2027 to test the system in orbit. Google has announced Project Suncatcher, a research initiative that explores the concept of solar-powered AI data centres orbiting in space. The concept proposes compact constellations of satellites equipped with Google's Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), which would draw continuous energy from the Sun and communicate via high-speed optical links. In a recent preprint paper titled "Towards a Future Space-Based, Highly Scalable AI Infrastructure System Design," the company provided an overview of the project. The study claims that launching AI computing infrastructure into orbit could unlock enormous energy potential while reducing reliance on terrestrial resources. Reports state that solar panels in orbit can run almost continuously and generate up to eight times as much energy as those on Earth, eliminating the need for substantial battery backups. To make this logical, Google engineers are addressing a number of key challenges, including maintaining tight satellite formations and ensuring high-bandwidth, low-latency data transfers on par with Earth-based data centres. Early lab tests have shown 1.6 Tbps transmission speeds over optical inter-satellite links. However, radiation tolerance poses yet another challenge. Tests on Google's Trillium Cloud TPUs show that the chips are surprisingly resilient, withstanding radiation levels nearly three times those expected for low-Earth orbit missions. Economically, falling launch costs could make the concept more feasible by the mid-2030s. According to Google's analysis, if launch prices fall below $200 per kg, the cost of operating space-based compute systems could match the energy costs of terrestrial data centres. Furthermore, Google now aims to work with Planet Labs and launch two prototype satellites by 2027. If successful, Project Suncatcher will be the first step towards testing space-based AI computing and the future of scalable, sustainable AI infrastructure that is literally powered by the Sun.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Google unveils Project Suncatcher, a moonshot initiative to deploy solar-powered satellites equipped with TPUs in space-based data centers. The project aims to harness continuous solar power and overcome terrestrial energy constraints for AI computing.

Google's Ambitious Space-Based AI Vision

Google has unveiled Project Suncatcher, an ambitious "moonshot" initiative aimed at deploying AI data centers in space using solar-powered satellites equipped with the company's Tensor Processing Units (TPUs). The project represents a bold attempt to address the mounting energy constraints and infrastructure challenges facing terrestrial AI data centers

1

.

Source: Digit

The concept involves placing satellites in a dawn-dusk sun-synchronous low-earth orbit, ensuring nearly constant sunlight exposure. This orbital positioning would allow solar panels to operate at up to eight times the efficiency of Earth-based installations, providing a continuous source of clean energy for power-hungry AI computations

3

.

Source: The Register

Technical Challenges and Engineering Solutions

The project faces significant engineering hurdles that Google acknowledges will require years to overcome. One of the primary challenges involves maintaining high-speed communication between orbiting satellites. Unlike terrestrial data centers that rely on optical fiber connections, Project Suncatcher would need wireless solutions capable of operating at tens of terabits per second

1

.Google has demonstrated early success with bidirectional speeds up to 1.6 Tbps in Earth-based testing, but scaling this technology for space presents unique obstacles. The physics of signal transmission requires satellites to maintain extremely close proximity—within a kilometer or less—to achieve the necessary power levels. Google's simulations suggest satellites positioned several hundred meters apart would require only "modest station-keeping maneuvers"

1

.

Source: Tom's Hardware

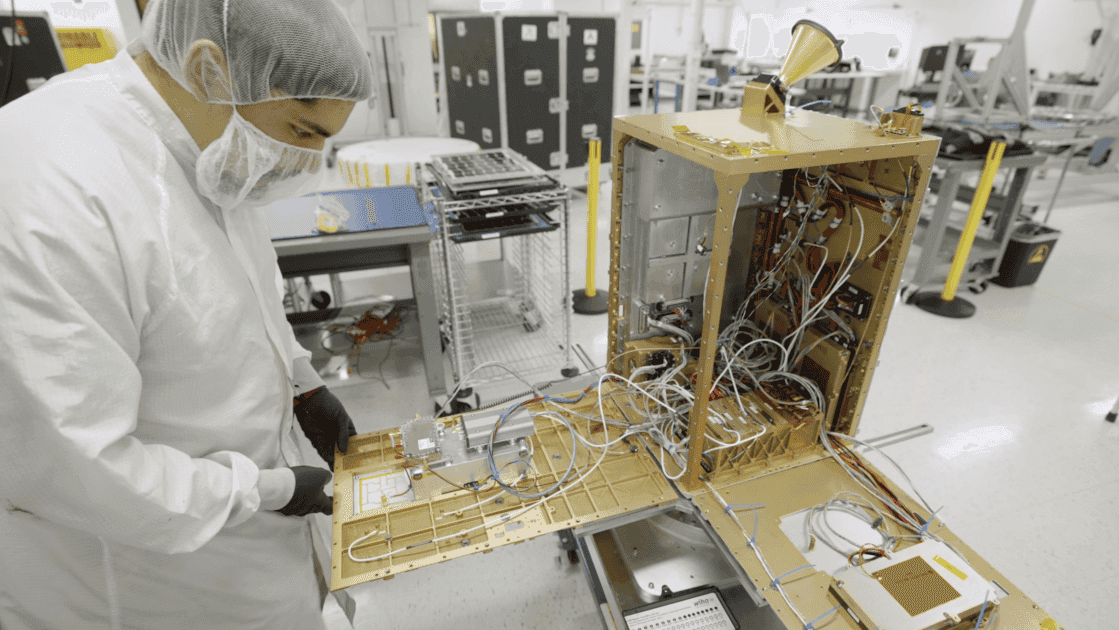

Radiation resistance represents another critical challenge. Space-based electronics face constant bombardment from solar radiation and cosmic rays. Google has been testing its latest v6e Cloud TPU (Trillium) chips using a 67MeV proton beam to simulate space conditions. Results showed that while memory components were most vulnerable, TPUs could handle approximately three times the expected radiation dose before experiencing data corruption

1

.Timeline and Economic Projections

Google plans to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027 in partnership with satellite company Planet Labs

4

. These initial missions will test the viability of TPUs in space and validate the communication systems necessary for distributed computing.The economic feasibility of the project hinges on dramatic reductions in launch costs. Current launch prices make space-based data centers prohibitively expensive, but Google projects that costs could fall to as low as $200 per kilogram by the mid-2030s. At this price point, space-based data centers could become economically comparable to terrestrial facilities on a per-kilowatt basis

4

.Related Stories

Industry Context and Competition

Google's announcement comes amid growing interest from other tech giants in space-based computing infrastructure. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk recently indicated his company's intention to build orbiting data centers, leveraging the existing Starlink satellite constellation

4

. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has also predicted that gigawatt-scale data centers will fill Earth's orbit within two decades5

.The startup Starcloud has already achieved a milestone by successfully launching its first test satellite equipped with an Nvidia AI GPU, demonstrating that the concept is moving from theoretical to practical implementation

4

.Environmental and Practical Implications

Project Suncatcher addresses several pressing issues with terrestrial data centers, which are increasingly viewed as environmentally problematic due to their massive energy consumption and water usage. Many communities now oppose new data center construction due to concerns about power grid strain and utility cost increases

3

.However, space-based solutions introduce their own concerns, including increased orbital debris and potential interference with astronomical observations. The project would require managing dense satellite constellations in formations tighter than any currently operational system

5

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[3]

[5]

Related Stories

Nvidia H100 GPUs Set to Launch Into Orbit as Startups Pioneer Space-Based AI Data Centers

22 Oct 2025•Technology

AI Trained in Space as Tech Giants Race to Build Orbiting Data Centers Powered by Solar Energy

11 Dec 2025•Technology

Google Plans Space Data Centers to Power AI with Solar Energy, Targets 2027 Launch

02 Dec 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Nvidia and Meta forge massive chip deal as computing power demands reshape AI infrastructure

Technology

3

ChatGPT cracks decades-old gluon amplitude puzzle, marking AI's first major theoretical physics win

Science and Research