Power Crisis Becomes Critical Bottleneck in Global AI Infrastructure Race

13 Sources

13 Sources

[1]

Altman and Nadella need more power for AI, but they're not sure how much

How much power is enough for AI? Nobody knows, not even OpenAI CEO Sam Altman or Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella. That has put software-first businesses like OpenAI and Microsoft in a bind. Much of the tech world has been focused on compute as a major barrier to AI deployment. And while tech companies have been racing to secure power, those efforts have lagged GPU purchases to the point where Microsoft has apparently ordered too many chips for the amount of power it has contracted. "The cycles of demand and supply in this particular case you can't really predict," Nadella said on the BG2 podcast. "The biggest issue we are now having is not a compute glut, but it's a power and it's sort of the ability to get the [data center] builds done fast enough close to power." "If you can't do that, you may actually have a bunch of chips sitting in inventory that I can't plug in. In fact, that is my problem today. It's not a supply issue of chips, it's the fact that I don't have warm shells to plug into," Nadella added, referring to the commercial real estate term for buildings ready for tenants. In some ways, we're seeing what happens when companies accustomed to dealing with silicon and code, two technologies that scale and deploy quickly compared with massive power plants, need to ramp up their efforts in the energy world. For more than a decade, electricity demand in the U.S. was flat. But over the last five years, demand from data centers has begun to ramp up, outpacing utilities' plans for new generating capacity. That has led data center developers to add power in so-called behind-the-meter arrangements, where electricity is fed directly to the data center, skipping the grid. Altman, who was also on the podcast, thinks that trouble could be brewing: "If a very cheap form of energy comes online soon at mass scale, then a lot of people are going to be extremely burned with existing contracts they've signed." "If we can continue this unbelievable reduction in cost per unit of intelligence -- let's say it's been averaging like 40x for a given level per year -- you know, that's like a very scary exponent from an infrastructure buildout standpoint," he said. Altman has invested in nuclear energy, including fission startup Oklo and fusion startup Helion, along with Exowatt, a solar startup that concentrates the Sun's heat and stores it for later use. None of those are ready for widespread deployment today, though, and fossil-based technologies like natural gas power plants take years to build. Plus, orders placed today for new gas turbine likely won't get fulfilled until later this decade. That's partially why tech companies have been adding solar at a rapid clip, drawn to the technology's inexpensive cost, emissions-free power, and ability to deploy rapidly. There might be subconscious factors at play, too. Photovoltaic solar is in many ways a parallel technology to semiconductors, and one that has been derisked and commoditized. Both PV solar and semiconductors are built on silicon substrates, and both roll off production lines as modular components that can be packaged together and tied into parallel arrays that make the completed part more powerful than any individual module. Because of solar's modularity and speed of deployment, the pace of construction is much closer to that of a data center. But both still take time to build, and demand can change much more quickly than either a data center or solar project can be completed. Altman admitted that if AI gets more efficient or if demand doesn't grow as he expects, some companies might be saddled with idled power plants. But from his other comments, he doesn't seem to think that's likely. Instead, he appears to be a firm believer in Jevons Paradox, which says that more efficient use of a resource will lead to greater use, increasing overall demand. "If the price of compute per like unit of intelligence or whatever -- however you want to think about it -- fell by a factor of a 100 tomorrow, you would see usage go up by much more than 100 and there'd be a lot of things that people would love to do with that compute that just make no economic sense at the current cost," Altman said.

[2]

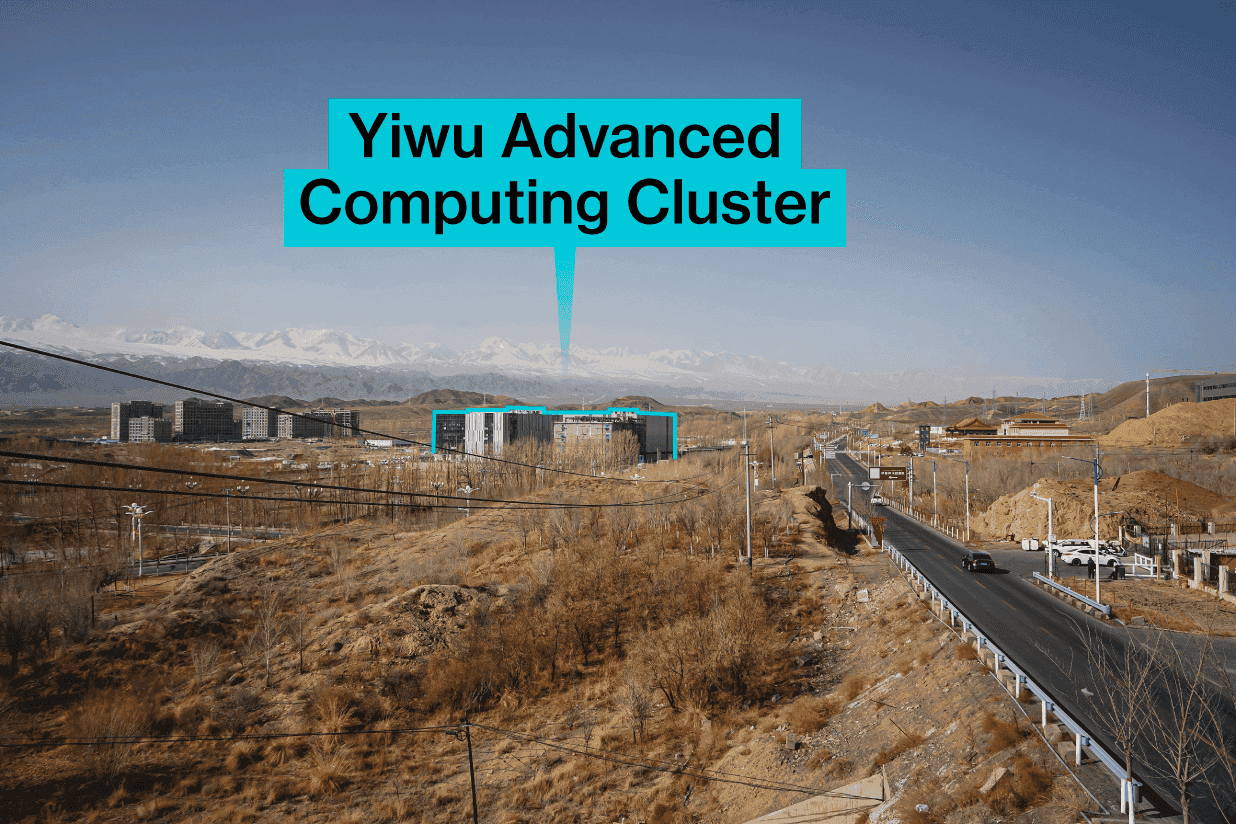

China and America's AI war isn't just about compute, it's about energy -- energy subsidies promote homegrown chip push, amid data center energy squeeze

Banning Nvidia's more efficient GPUs comes at the price of power Local Chinese governments have begun issuing attractive power incentives and subsidies to Chinese tech companies, including ByteDance, Alibaba, and Tencent, according to a new report. Designed to cut energy bills for affected companies, the subsidies are an effort to further curtail the use of foreign chips, such as Nvidia's powerful AI-capable hardware. The incentives are also intended to bolster the local production of Chinese chips and AI processors. The past year has seen the U.S. and China tussle repeatedly over access to the latest hardware, namely, Nvidia GPUs. On-again, off-again tariffs, trade export blocks, and threats to restrict access to rare earth minerals have ultimately led to China pushing to accelerate the development of its own AI hardware, like GPUs and ASICs for inference and, aspirationally, AI training. To encourage their use, the country has effectively blocked Chinese tech companies from using Nvidia GPUs and pushed them towards domestic alternatives instead. The only problem is, Nvidia GPUs are at the top of the pile for a reason: they're incredibly fast, and far more efficient than the alternatives from the likes of Huawei and Cambrion. Specifically, Nvidia's GPUs are so far ahead in terms of per-watt efficiency that Chinese alternatives are generations behind, perhaps due to export restrictions on ASML's latest EUV lithography tools, which China doesn't have access to. This means that chips developed natively in the region will lag behind the rest of the world. Despite these limitations, companies such as Huawei continue to make efforts to compete with Nvidia. Companies like Huawei are developing high-performance chips, clustering them together and pumping them full of additional power, but that makes them less efficient, in turn leading to rapidly rising energy costs. These rising energy costs have led to grumbling in the Chinese tech industry, so Chinese government officials are looking to sweeten the deal with proposed energy subsidies. Regions like Gansu, Guizhou, and Inner Mongolia, where data centers are heavily concentrated, have begun offering large energy subsidies, cutting bills by as much as 50% in some cases. The catch is that data centers that use GPUs and chips from foreign manufacturers, like Nvidia, are exempt from the incentives. This plan has the dual benefit for local governments of meeting central party demands, while also helping attract data center production to their region, as local governments compete for contracts. These subsidies are funded by the $50 billion Big Fund III, which China set up to compete with the U.S., in order to bolster its chip design and fabrication industry, thereby bolstering the country's AI efforts. China is ultimately expected to spend close to $100 billion in government investment on accelerating the development of these domestic industries this year. Across the Pacific, American companies like OpenAI, Nvidia, Oracle, and CoreWeave are all collectively investing hundreds of billions of dollars in AI infrastructure, building out enormous data centers and circularly buying each other's services, hardware, and software. Chinese tech companies are looking to compete, although Goldman Sachs has predicted that those companies will "only" invest around $70 billion in data centers in 2026. Despite greater investment in the U.S., it might also be energy which proves the bottleneck. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said that the company is sitting on unused GPUs and AI chips that it can't use because it doesn't have the energy to run them. Elon Musk's xAI has been buying up gas turbines by the thousands and is even trying to import a power station. One thing is clear: massive AI data center buildouts are causing a squeeze in energy supplies across the board. Small, modular nuclear reactors could be one way around the issue, but it's far from a simple, quick solution. Power may well remain in short supply, even with all the solar coming online around the world. Especially in China, where the country built more solar power in the first half of 2025 than the U.S. has in its entire history. China's advancements in nuclear and hydropower could give it a distinct advantage in the years to come, if energy proves to be a more significant bottleneck for AI than pure compute performance.

[3]

Power crunch threatens to derail AI datacenter construction

A survey of datacenter professionals reveals that supply chain constraints and power availability are hampering the industry's efforts to scale datacenter capacity. Turner & Townsend's 2025-2026 Datacenter Construction Cost Index report, based on 300+ projects across 20+ countries and input from 280 industry experts, identifies critical barriers to meeting AI infrastructure demand. Nearly half of respondents (48 percent) cite power access as the biggest scheduling constraint, with grid connection wait times stretching years. In the US, for example, some requests face a seven-year queue, although the US Energy Secretary is taking steps to address this. In Britain, developers similarly report delays requiring substation upgrades worth hundreds of millions. The scale problem is the sheer amount of AI infrastructure currently being planned: OpenAI's disclosed projects alone would consume 55.2 gigawatts -- enough to power 44.2 million households, nearly triple California's housing stock. Datacenters compete with housing and manufacturing for limited grid capacity across the US, UK, and Europe. Deloitte warned in June that power requred by AI datacenters in the US may be 30 times greater inside a decade with 5 GW facilities already in the planning pipeline. Turner & Townsend recommends on-site generation, energy storage or grid-independent power solutions to support projects, especially for AI facilities. The report's authors propose renewables for energy creation though in reality this is likely to be generators driven by gas-powered turbines. In adition to the power puzzle, 83 percent of industry professionals believe local supply chains cannot support the advanced cooling technology required for high-density AI deployments. There is a growing gap in the market between traditional and AI datacenters, with the latter proving more costly to design and build. Turner & Townsend's report says air-cooled facilities have experienced a 5.5 percent cost-per-watt increase (down from 9 percent in 2024). In contrast, AI-optimized liquid-cooled facilities cost 7-10 percent more than equivalent air-cooled designs, the report adds. The advice to datacenter operators? Review procurement models to bolster supply chains and support the delivery of the most urgently needed AI datacenters. Turner & Townsend North America datacenter sector lead Paul Barry noted that AI farms are increasingly high on the priority list for many governments, but investment is at risk. "Power availability remains a critical barrier, with long-lead times for grid connection the main constraint. There is also stronger competition than ever before for power due to increased business and consumer demand placing added pressure on grids," he said. "Developers and operators must adapt quickly to the evolving market landscape. AI datacenters are more advanced, and by extension, costlier. They come with greater power demands and modern cooling solutions." Hardware may another factor that holds back construction. Chip makers may struggle to produce enough supply to support the massive AI buildout forecasts. ®

[4]

How many 'bragawatts' have the hyperscalers announced so far?

The financing package stitched together for Meta's humongous Hyperion data centre campus in Louisiana made Alphaville curious about just how much energy the new AI infrastructure will consume if it all comes online. After all, massive new projects are being announced almost every week, in what even KKR's digital infrastructure lead called a "bragawatts" phenomenon in MainFT on Monday. The latest example is OpenAI on Thursday revealing plans for a 1+ gigawatt data centre hub in Michigan. Together with previously announced "Stargate" projects this brings the total to over 8 gigawatts -- close to the 10 target it floated earlier this year. This will cost over $450bn over the next three years, according to the company that spends more on marketing and employee stock options than it makes in revenue. So how many data centre projects have now been started or announced? Which ones will actually happen and which ones are fantasy? As Barclays noted last week, tracking "what is real vs. speculative is a full-time job", but the bank has forced some poor sell-side plebs to at least tally all the announcements and collect some rudimentary details. So what is the total so far? With OpenAI's Michigan project they now total 46 gigawatts of computing power. Apologies for the virtual shouting, but this seems a bit mad. These centres will cost $2.5tn to build, according to Barclays, to service an industry that still doesn't turn a profit. But the maddest bit arguably is how much energy they will require once completed. Using Barclays' 1.2 "Power Use Effectiveness" ratio, all these data centres -- if they are all completed -- would need 55.2 gigawatts of electricity to function at full capacity. If we also use Barclays' rule of thumb that 1 gigawatt can power over 800,000 American homes, it means that these data centres will consume as much energy as 44.2mn households -- almost three times California's entire housing stock.* So where is the energy all coming from? Well, OpenAI's Michigan Stargate is perhaps instructive. All the electricity for Michigan's Stargate site will come from DTE Energy, which stressed in its third-quarter earnings last week that it wouldn't negatively affect ordinary consumers, and said that Developer Related Companies -- which is actually building the campus -- would cover the costs of the new power infrastructure needed: The new electricity demand will be supported with existing capacity and new energy storage investments which will be paid for by the data center. This data center growth will create substantial affordability benefits for existing customers as DTE sells excess generation, and contract terms will also ensure that the data center absorbs all new costs required to serve them. However, DTE increased its five-year investment plan by $6.5bn, which Barclays noted included replacing one of its coal plants with gas turbines. And this seems to be the emerging norm. In many other cases, the data centre business plans include the installation of at least some of the energy generation. For example, Meta's Prometheus campus includes plans for 516 megawatts from solar and gas turbines. Amazon's Pennsylvania data centres have been promised 1.9 gigawatts from Talen Energy's nuclear power plant. However, in many cases the regional power grids still seem hopelessly inadequate to cope with demand possibly surging over the next few years. Beyond the sheer scale, the nature of the AI-related power demand is also particularly problematic. As a recent Nvidia report noted (with Alphaville's emphasis below): Unlike a traditional data center running thousands of uncorrelated tasks, an AI factory operates as a single, synchronous system. When training a large language model (LLM), thousands of GPUs execute cycles of intense computation, followed by periods of data exchange, in near-perfect unison. This creates a facility-wide power profile characterized by massive and rapid load swings. This volatility challenge has been documented in joint research by NVIDIA, Microsoft, and OpenAI on power stabilization for AI training data centers. The research shows how synchronized GPU workloads can cause grid-scale oscillations. The power draw of a rack can swing from an "idle" state of around 30% to 100% utilization and back again in milliseconds. This forces engineers to oversize components for handling the peak current, not the average, driving up costs and footprint. When aggregated across an entire data hall, these volatile swings -- representing hundreds of megawatts ramping up and down in seconds -- pose a significant threat to the stability of the utility grid, making grid interconnection a primary bottleneck for AI scaling. That's presumably why the likes of the Michigan Stargate project will include lots of energy storage. But it also explains why OpenAI this summer asked the Trump administration to ensure that the US brings a massive 100 gigawatts a year online to feed the gaping AI maw. So how likely is this to all pan out the way the AI visionaries et al envisage it? Well, OpenAI weirdly warned that the US now faced an "electron gap" versus China -- a nod to Cold War "missile gap" that famously proved to be complete and utter hogwash. Even at the time, the CIA knew it was baloney. Sure, China might have built a lot power generation lately, but that OpenAI would invoke such an well-known mirage is . . . curious. However, once the hype dies down at least we might be left with a bigger, stronger and cheaper energy grid in its wake?

[5]

China's key weapons in its AI battle with the U.S. -- massive Huawei chip clusters and cheap energy

China is focusing on large language models in the artificial intelligence space. It's well known that Chinese semiconductors designed for artificial intelligence cannot compete with the American firm Nvidia. Yet, China has managed to continue developing highly advanced AI models, with many being run on homegrown chips. China's secret? A plethora of cheap energy and giant chip clusters from the China's tech champion Huawei that are underpinning AI advances in the country's race against the U.S. "China is striving for self-sufficiency across the AI stack, as it sees AI as a strategic technology for national and economic security," Wendy Chang, senior analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), told CNBC. With the world's second-largest economy being cut off from certain tech due to U.S. restrictions, and Beijing opting to shun Nvidia chips, questions have swirled over its ability to compete in the field of AI. Despite these geopolitical challenges domestic technology companies from Alibaba to DeepSeek have managed to develop and release high performing AI models, with many being trained on homegrown chips.

[6]

Microsoft CEO says the company doesn't have enough electricity to install all the AI GPUs in its inventory - 'you may actually have a bunch of chips sitting in inventory that I can't plug in'

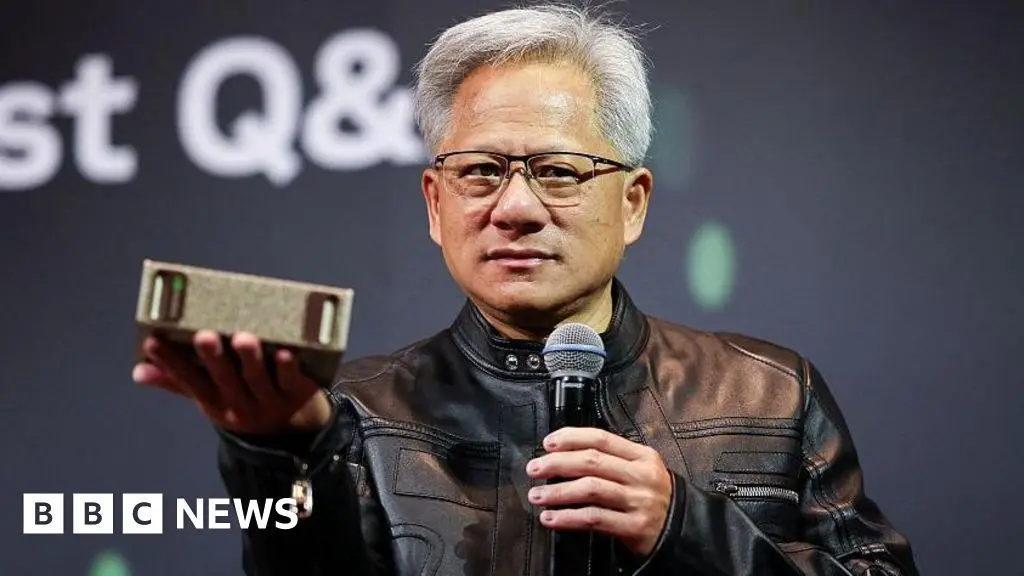

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said during an interview alongside OpenAI CEO Sam Altman that the problem in the AI industry is not an excess supply of compute, but rather a lack of power to accommodate all those GPUs. He said this on YouTube in response to Brad Gerstner, the host of Bg2 Pod, when asked whether Nadella and Altman agreed with Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, who said there is no chance of a compute glut in the next two to three years. "Well, I mean, I think the cycles of demand and supply in this particular case, you can't really predict, right? The point is: what's the secular trend? The secular trend is what Sam (the OpenAI CEO) said, which is, at the end of the day, because quite frankly, the biggest issue we are now having is not a compute glut, but it's power -- it's sort of the ability to get the builds done fast enough close to power," Satya said in the podcast. "So, if you can't do that, you may actually have a bunch of chips sitting in inventory that I can't plug in. In fact, that is my problem today. It's not a supply issue of chips; it's actually the fact that I don't have warm shells to plug into." AI's power consumption has been a topic many experts have discussed since last year. This came to the forefront as soon as Nvidia fixed the GPU shortage, and many tech companies are now investing in research in small modular nuclear reactors to help scale their power sources as they build increasingly large data centers. This has already caused consumer energy bills to skyrocket, showing how the AI infrastructure being built out is negatively affecting the average American. OpenAI has even called on the federal government to build 100 gigawatts of power generation annually, saying that it's a strategic asset in the U.S.'s push for supremacy in its AI race with China. This comes after some experts said Beijing is miles ahead in electricity supply due to its massive investments in hydropower and nuclear power. Aside from the lack of power, they also discussed the possibility of more advanced consumer hardware hitting the market. "Someday, we will make a[n] incredible consumer device that can run a GPT-5 or GPT-6-capable model completely locally at a low power draw -- and this is like so hard to wrap my head around," Altman said. Gerstner then commented, "That will be incredible, and that's the type of thing that scares some of the people who are building, obviously, these large, centralized compute stacks." This highlights another risk that companies must bear as they bet billions of dollars on massive AI data centers. While you would still need the infrastructure to train new models, the data center demand that many estimate will come from the widespread use of AI might not materialize if semiconductor advancements enable us to run them locally. This could hasten the popping of the AI bubble, which some experts like Pat Gelsinger say is still several years away. But if and when that happens, we will be in for a shock as even non-tech companies would be hit by this collapse, exposing nearly $20 trillion in market cap.

[7]

China's half-price electricity deal tempts its tech titans to replace foreign chips

Major tech firms face tough trade-offs between efficiency and political loyalty China is reportedly offering major home-grown cloud and internet companies including Alibaba, ByteDance, and Tencent electricity subsidies which could reduce energy costs by as much as half. Reports from the Financial Times claim the initiative aims to encourage these firms to run their data center operations on chips produced by local manufacturers such as Huawei and Cambricon. By targeting large data center clusters, local authorities hope to maintain momentum in artificial intelligence development while adhering to national directives favoring domestic supply chains. The move follows a series of complaints that domestic chips are less energy-efficient than Nvidia's widely-used AI chips. Nvidia's chips are no longer available to Chinese buyers due to trade restrictions imposed by the United States, but the decision to link cheaper power to the use of Chinese hardware reflects a broader attempt to protect and expand the nation's semiconductor ecosystem. The measure also exposes tensions between industrial policy and operational efficiency. Many firms have reportedly struggled with higher running costs since shifting to local chipsets, whose performance and power efficiency are still seen as trailing their Western equivalents. The subsidies, therefore, appear designed to offset these disadvantages by lowering the burden of electricity consumption in energy-intensive data center facilities. Provinces such as Gansu, Guizhou, and Inner Mongolia, key hubs for China's growing network of cloud and AI infrastructure, are said to be leading the rollout of these discounts. The policy reportedly allows qualifying facilities to cut their energy bills by up to 50%, but only if their systems rely on domestic CPU and accelerator units rather than imported ones. While the plan signals Beijing's determination to reduce dependence on foreign technology, its long-term effectiveness remains uncertain. Subsidized electricity might temporarily mask the efficiency gap between Chinese processors and Nvidia's leading designs, yet it may not solve the underlying performance issue. For major platforms deploying AI tools across vast server farms, the trade-off between political alignment and computational capability could prove costly. As of the time of writing, there is no official confirmation of the scheme, suggesting the policy may still be in a testing phase.

[8]

If Microsoft can't source enough electricity to power all the AI GPUs it has, you have to wonder how Amazon is going to cope in its new $38 billion deal with OpenAI

To keep the AI juggernaut rolling ever forward, you might think that the biggest companies in artificial intelligence desperately need ridiculous numbers of AI GPUs. According to Microsoft, though, the issue isn't a compute or hardware limit, it's that there's not enough electrical power to run it all. And if that's the case, it raises the question as to how Amazon is going to cope now that it's signed a $38 billion, multi-year deal with OpenAI to give the company access to its servers. It was Microsoft's CEO, Satya Nadella, who made the point about insufficient power in a 70-minute interview (via Tom's Hardware) with YouTube channel Bg2 Pod, alongside OpenAI's boss, Sam Altman. It came about when the interview's host, Brad Gerstner, mentioned that Nvidia's Jen-Hsun Huang had said that there was almost zero chance of there being a 'compute glut' within the next couple of years (and by that, he means an excess of AI GPUs). "The biggest issue we are now having is not a compute glut, but it's power," replied Nadella. "It's sort of the ability to get the builds done fast enough close to power. So, if you can't do that, you may actually have a bunch of chips sitting in inventory that I can't plug in. In fact, that is my problem today. It's not a supply issue of chips; it's actually the fact that I don't have warm shells to plug into." The warm shells that he refers to aren't tasty tacos; they're hubs already connected with the relevant power and other facilities required, ready to be loaded up with masses of AI servers from Nvidia. What Nadella is effectively saying is that getting hold of GPUs isn't the problem, it's accessing cheap enough electricity to run them all. That's not necessarily just a case of there just not being sufficient power stations -- it matters a great deal where they are, because while one can just dump a building down almost anywhere, if the local grid can't cope with the enormous power demands of tens of thousands of Nvidia Hopper and Blackwell GPUs, then there's no point in building the shell in the first place. When I heard Microsoft's CEO make that comment, I immediately recalled another news story I'd read today: OpenAI's $38 billion deal with Amazon that will give it access to AWS's AI servers. OpenAI already has such an agreement with Microsoft to use its Azure services, with the latter pumping money into the former as well. "OpenAI will immediately start utilizing AWS compute as part of this partnership, with all capacity targeted to be deployed before the end of 2026, and the ability to expand further into 2027 and beyond," the announcement says. "The infrastructure deployment that AWS is building for OpenAI features a sophisticated architectural design optimized for maximum AI processing efficiency and performance. Clustering the NVIDIA GPUs -- both GB200s and GB300s -- via Amazon EC2 UltraServers on the same network." Does this mean AWS is effectively handing over all its Nvidia AI GPUs to OpenAI over the next few years, or will it expand its AI network by building new servers? It surely can't be the former, as AWS offers its own AI services, so the most logical explanation is that Amazon is going to buy more GPUs and build fresh data centers. But if Microsoft can't power all the AI GPUs it has now, how on Earth is Amazon going to do it? Research by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggests that within three years, the total electrical energy consumption by data centers will reach as high as 580 trillion Wh. According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, that would put AI consuming as much electricity as 22% of all US households per year. To meet this enormous demand, some companies are looking at restarting old nuclear power stations, or in the case of Google, building a raft of new ones. While the former is hoped to be ready by 2028, it will only produce 7.3 TWh per annum at best -- a mere 1.3% of the total projected power demand. This is clearly not going to be a valid long-term solution to AI's energy problem. With so much capital now invested in AI, it's not going to disappear without a trace (though that would solve the question of powering it all), so the only way forward for Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft is to either build vastly more power stations, design and build specialised low-energy AI ASICs (in the same way that bitcoin mining has gone this way), or more likely, both. This generates a new question: Where is the money required for all of this going to come from? Answers on a postcard, please.

[9]

Microsoft faces power shortages despite holding vast inventories of idle GPUs

OpenAI urges the government to massively expand national energy generation capacity Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has drawn attention to a less discussed obstacle in the AI race - a shortage not of processors but of power. Speaking on a podcast alongside OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, Nadella said Microsoft has, "a bunch of chips sitting in inventory that I can't plug in." "The biggest issue we are now having is not a compute glut, but it's power -- it's sort of the ability to get the builds done fast enough close to power," Nadella added, "in fact, that is my problem today. It's not a supply issue of chips; it's actually the fact that I don't have warm shells to plug into." Nadella explained that while the supply of GPUs is currently sufficient, the lack of suitable facilities to power them has become a critical issue. In this context, he described "warm shells" as empty data center buildings ready to house hardware but dependent on access to adequate energy infrastructure. This shows that the explosive growth of AI tools has exposed vulnerabilities, and the demand for computing capacity has outpaced the ability to construct and power new data center sites. Energy planning across the technology industry is such a big issue, and even large companies like Microsoft with vast resources still struggle to keep up. To solve this issue, some firms, including major cloud providers, are now researching nuclear-based energy solutions to sustain their rapid expansion. Nadella's comments reflect a broader concern that AI infrastructure is stretching national electricity grids to their limits. As data center construction accelerates across the United States, power-intensive AI workloads have already begun influencing consumer electricity prices. OpenAI has even urged the US government to commit to building 100 gigawatts of new power generation capacity annually. It argues that energy security is becoming as important as semiconductor access in the competition with China. Analysts have pointed out Beijing's head start in hydropower and nuclear development could give it an advantage in maintaining AI infrastructure at scale. Altman also hinted at a potential shift toward more capable consumer devices that could one day run advanced models such as GPT-5 or GPT-6 locally. If CPU and chip innovation enable such low-power systems, much of the projected demand for cloud-based AI processing might disappear. This possibility presents a long-term risk for companies investing heavily in massive data center networks. Some experts believe such a shift could even accelerate the eventual bursting of what they describe as an AI-driven economic bubble, which could threaten trillions of dollars in market value should expectations collapse. Via TomsHardware

[10]

China Offers Cheaper Power to Local AI Firms Ditching NVIDIA Chips | AIM

The move follows complaints from Alibaba, ByteDance and Tencent, which have faced higher costs after Beijing restricted access to NVIDIA chips. China has introduced new subsidies that halve energy bills for primary data centres using domestic chips, aiming to strengthen its semiconductor industry and reduce reliance on US technology, the Financial Times reported, citing sources. Local governments in provinces such as Gansu, Guizhou and Inner Mongolia are offering discounts of up to 50% on electricity for facilities that adopt chips made by Chinese firms, including Huawei and Cambricon Technologies. The move follows complaints from tech giants like Alibaba, ByteDance and Tencent, which have faced higher costs after Beijing restricted access to NVIDIA's AI chips. The new policy aims to offset the increased electricity consumption of Chinese-made semiconductors, which are less energy-efficient than those made by NVIDIA, according to reports. The three companies have not yet responded to AIM's queries. Local authorities have been competing to attract large-scale data projects by combining power subsidies with cash grants. Some incentives can cover a data centre's operating costs for about a year. Industrial electricity prices in these western provinces are already approximately 30% lower than those in coastal China, and the subsidies will further reduce them to around RMB 0.4, or 5.6 US cents, per kilowatt-hour. By comparison, the average industrial electricity cost in the US is roughly 9.1 cents per kWh, according to the US Energy Information Administration. Beijing's latest measures underline its intent to develop a self-sufficient AI and semiconductor ecosystem amid ongoing tensions with the US. According to experts, Chinese chips reportedly consume 30-50% more power than NVIDIA's models to produce the same computing output. Huawei has sought to counter this by clustering multiple Ascend 910C chips to enhance performance, though this increases energy usage. Despite such challenges, China's centralised and relatively greener power grid offers cheaper energy than the US, with no imminent shortage.

[11]

Microsoft CEO Doesn't Want to Buy NVIDIA's AI GPUs "Beyond One Generation," Hints at a Compute Glut Driven by Energy Constraints

Microsoft's Satya Nadella has revealed the situation regarding the firm's AI GPU arsenal, claiming that there isn't enough space or energy available to bring additional compute power onboard. Recently, a thesis has emerged suggesting that NVIDIA and the AI industry will ultimately reach a point where there's excess computing, or the per-unit compute achievements gained by employing AI chips won't be sustainable for Big Tech. Commenting on NVIDIA's CEO mentioning about excess compute being 'non existent' for the next two to three years, Microsoft's CEO Satya Nadella believes (via BG2 podcast) that the industry is currently facing a 'power glut', which leads to AI chips sitting in inventory that cannot be "plugged in", so basically, another form of a compute glut. I mean, even the point is, what's the secular trend? The secular trend is what Sam said, which is at the end of the day, because quite frankly, the biggest issue we are now having is not a compute glut, but it's a power. So if you can't do that, you may actually have a bunch of chips sitting in inventory that I cannot plug in. In fact, that is my problem today, right? It's not a supply issue of chips. It's actually the fact that I don't have warm shells to plug into. Well, it's clear that the race for a compute buildout has reached a point where companies like Microsoft cannot accommodate additional chips in their respective configurations. The underlying reason why Nadella mentions a power glut is that with each generation, NVIDIA's rack-scale configurations have brought in massive power requirements, to such an extent that from Ampere to the next-gen Kyber rack design, rack TDPs are expected to increase by 100 times. When examining scaling laws and NVIDIA's efforts to advance architectural capabilities, it is certain that the industry will eventually encounter a roadblock where the energy infrastructure will not allow for the expansion of data centers. And, by the statement from Microsoft's CEO, the energy-compute constraint is already being witnessed. This is a concern being discussed by several experts; however, the efforts made to scale up the energy infrastructure are currently insufficient. Would the lack of energy lead to NVIDIA's chips not being sold? Well, Satya actually answered this, claiming that the demand in the short term is difficult to predict and is subject to how the supply chain progresses.

[12]

China going to win AI race thanks to cheaper electricity, warns NVIDIA CEO

The true AI bottleneck isn't chips or data but electricity access We've finally reached that stage of the AI arms race where securing compute isn't the primary concern for the world's leading (tech) powers. Access to gigawatt scale electricity has emerged as the single biggest bottleneck to launching the latest and greatest AI datacenters, something that's eventually going to tip the scales in China's favour, according to NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang. Speaking at the sidelines of the Future of AI Summit, Huang wasn't talking about algorithms or ambitions, but practicality. And he believes it's much easier for AI companies to access cheaper energy in China, he warned. While the West drowns in cynicism, red tape, and export bans, China is quietly building the future with cheap, abundant electricity. For a man whose company is now the world's most valuable by market cap, this is far from idle commentary. NVIDIA's entire AI empire is built on H100s, GB200s, and soon-to-be mythical Blackwell chips as the lifeblood of modern AI apps and services. But these chips are also insatiable energy hogs. And as Washington tightens export controls, Beijing is doubling down on energy access at a scale the US power grid simply can't support. Huang's frustration mirrors that of another tech titan - Microsoft's Satya Nadella - who recently offered his own sobering confession: "I've got GPUs sitting in inventory that I can't plug in." Imagine that. The CEO of the world's second-most valuable company, with billions of dollars' worth of state-of-the-art NVIDIA processors collecting dust because there's no electricity to run them. Unprecedented! Also read: Satya Nadella says Microsoft has GPUs, but no electricity for AI datacenters For years, big tech's scarcest resource was compute - how many NVIDIA chips you could hoard, rent, or smuggle through a supply chain bottleneck. Now, the great scarcity is power. Just for reference, a single hyperscale AI datacenter can draw up to 100 megawatts - enough to light 80,000 homes (in the US). Morgan Stanley projects they'll gulp over a trillion liters of water annually by 2028 just to keep cool. Microsoft, Google, and OpenAI are all scrambling for alternatives - from nuclear microreactors to space-based solar - but none of these will arrive in time for the next AI boom cycle. China, meanwhile, has turned energy access into an industrial weapon. In 2023, it added nearly 350 gigawatts of new generation capacity - more than the entire power output of the UK and Germany combined. It dominates 80% of global solar manufacturing, builds new coal and hydropower plants faster than the US can approve one, and operates the world's most advanced ultra-high-voltage transmission grid. The paradox Huang points out is brutal. The same US export controls designed to slow China's AI ascent may instead accelerate it. Cut off from NVIDIA's GPUs, Chinese chipmakers are scaling homegrown designs - and they've got the electricity to feed them. Meanwhile, America's AI giants are fighting each other (and state regulators) for megawatts. "Fifty new regulations" is how Huang described the US landscape, in stark contrast to China's decisiveness. Because before the future of artificial intelligence gets written in code running on the latest chips in datacenters, they still need to be turned on with electricity - a commodity that's fast becoming more precious with each passing day.

[13]

Satya Nadella says Microsoft has GPUs, but no electricity for AI datacenters

The AI revolution faces its most human constraint: the power grid Satya Nadella didn't mince his words. "I've got GPUs sitting in inventory that I can't plug in," he said - calmly, matter-of-factly - in a recent podcast. Let that sink in for a moment. This is the world's second-largest cloud company with a $3.86 trillion market cap, that has thousands of state-of-the-art AI processors ready to crunch intelligence into existence, and the thing stopping them from doing that is... electricity. Yes, electricity, and yes this is a tech titan from the US - not Ulhasnagar, which is prone to routine power cuts thanks to "load shedding." That's a humbling admission by the Microsoft CEO on behalf of an industry built on excess and abundance. For years, big tech's most urgent constraint was compute - how many NVIDIA H100s you could buy, rent, or smuggle through a supply chain bottleneck. But as Nadella and Sam Altman both hinted, the new scarcity isn't hardware. It's power - the simple, invisible current that keeps the datacenters humming, the water pumps spinning, the air conditioners cooling, and, by extension, the future of artificial intelligence alive and running. A large AI datacenter today gulps between 2-19 million liters of water every day - a small city's thirst to keep racks cool enough not to melt. Each rack of servers can draw 130 kilowatts or more, and the largest campuses have deployed 100 megawatts on average and are planning / building for gigawatts of capacity. To put that into perspective, that's enough electricity to light up hundreds of thousands of homes - for one facility, according to a September 2025 study. By 2028, AI datacenters are projected to consume over 1 trillion liters of water a year, according to Morgan Stanley. That's before you factor in the indirect water cost of generating all that power in the first place. Also read: NVIDIA's Kari Briski believes open models will define the next era of AI What we're watching now is the industrialization of AI at an unprecedented scale. And as ironical as it may sound, Silicon Valley, once defined by its clean abstractions, is suddenly constrained by the same dirty physics as a coal plant. The Great AI Age that big tech is sprinting to manifest (at the cost of humans laid off in the process), brought to a grinding halt not by moral panic or regulatory overreach, but by the wall socket. Datacenters that can't plug in. CEOs that can't turn on their GPUs because the grid would groan under the load. The term "data center shell," which Nadella used so casually, now sounds faintly apocalyptic - gleaming buildings full of idle hardware, waiting for power that may not come soon enough. And this is where the story stops being funny. Because when companies with trillion-dollar valuations start competing for finite megawatts, the problem starts to appear infrastructural. Every new AI cluster must now negotiate not just with regulators but with rivers and reservoirs, with transmission lines and the people who depend on them. The race to build smarter machines is bumping up against the literal limits of the planet's water and electricity plumbing. The next frontier of artificial intelligence isn't abstract at all - it's geographic, environmental, political. Maybe that's the real revelation in Nadella's comment. That AI's future will be written not in code, but depend on unlocking kilowatts.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Tech giants face unprecedented energy challenges as AI data centers demand massive power capacity, with Microsoft reporting unused GPU inventory due to power shortages while China leverages energy subsidies to compete with U.S. AI infrastructure.

The Power Predicament

The artificial intelligence revolution has hit an unexpected roadblock: electricity. Major tech companies are discovering that their ambitious AI expansion plans are being constrained not by chip availability or computational capacity, but by the fundamental challenge of securing adequate power infrastructure

1

.

Source: Digit

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella revealed a striking paradox during a recent podcast appearance: "It's not a supply issue of chips, it's the fact that I don't have warm shells to plug into." The company has reportedly ordered more GPUs than it can power, leaving expensive hardware sitting unused in inventory

1

. This represents a fundamental shift from the traditional bottlenecks that have historically constrained technology deployment.Unprecedented Scale of Demand

The magnitude of power requirements for AI infrastructure has reached staggering proportions. According to recent analysis, announced data center projects now total 46 gigawatts of computing power, requiring an estimated 55.2 gigawatts of electricity to function at full capacity

4

. To put this in perspective, this amount of energy could power 44.2 million American households—nearly three times California's entire housing stock.

Source: The Register

OpenAI's recently announced Michigan data center hub alone will consume over 1 gigawatt, adding to the company's growing portfolio of "Stargate" projects that collectively target 10 gigawatts of capacity

4

. The total cost for these facilities is projected at $2.5 trillion, serving an industry that has yet to demonstrate consistent profitability.Grid Infrastructure Challenges

The power crisis extends beyond simple capacity issues to fundamental grid infrastructure limitations. A survey of datacenter professionals found that 48% cite power access as the biggest scheduling constraint, with grid connection wait times stretching years

3

. In the United States, some power requests face seven-year queues, while British developers report delays requiring substation upgrades worth hundreds of millions of dollars.The nature of AI workloads compounds these challenges. Unlike traditional data centers running diverse, uncorrelated tasks, AI facilities operate as synchronized systems where thousands of GPUs execute intense computation cycles in unison

4

. This creates massive power swings that can oscillate from 30% to 100% utilization in milliseconds, forcing engineers to oversize components and threatening grid stability.Related Stories

China's Strategic Energy Advantage

While American companies struggle with power constraints, China has identified energy as a strategic weapon in the global AI competition. Local Chinese governments have begun offering substantial energy subsidies—cutting bills by up to 50% in regions like Gansu, Guizhou, and Inner Mongolia—but only for companies using domestically produced chips

2

.

Source: TechRadar

This policy serves dual purposes: encouraging adoption of Chinese-made AI hardware while reducing dependence on foreign technology. Despite Chinese chips being less efficient than Nvidia's offerings—requiring more power for equivalent performance—the government subsidies effectively offset the energy penalty

5

. The subsidies are funded through China's $50 billion Big Fund III, part of nearly $100 billion in government investment aimed at accelerating domestic chip development.Industry Response and Future Outlook

Tech leaders are pursuing various strategies to address the power shortage. OpenAI's Sam Altman has invested in nuclear energy startups including Oklo and Helion, as well as solar concentration company Exowatt

1

. However, these technologies remain years from widespread deployment, forcing companies to rely on faster-deploying solutions like solar panels and natural gas turbines.The industry faces a fundamental uncertainty about future power requirements. Altman acknowledges that if AI becomes significantly more efficient or demand growth slows, companies could find themselves with stranded power assets. Conversely, he believes in Jevons Paradox—that efficiency improvements will drive even greater overall demand, potentially requiring the 100 gigawatts annually that OpenAI has requested from the Trump administration

4

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

[3]

Related Stories

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang Warns China Could Win AI Race Amid Trade War Tensions

06 Nov 2025•Policy and Regulation

Nvidia CEO warns China's AI infrastructure advantage could reshape the global AI race

07 Dec 2025•Business and Economy

China's Ambitious AI Data Center Plans Raise Questions About Chip Acquisition

10 Jul 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with Defense Production Act over AI military use restrictions

Policy and Regulation

2

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

3

Anthropic accuses Chinese AI labs of stealing Claude through 24,000 fake accounts

Policy and Regulation