Trump's Controversial AI Chip Deal with Nvidia and AMD Reshapes US-China Tech Relations

6 Sources

6 Sources

[1]

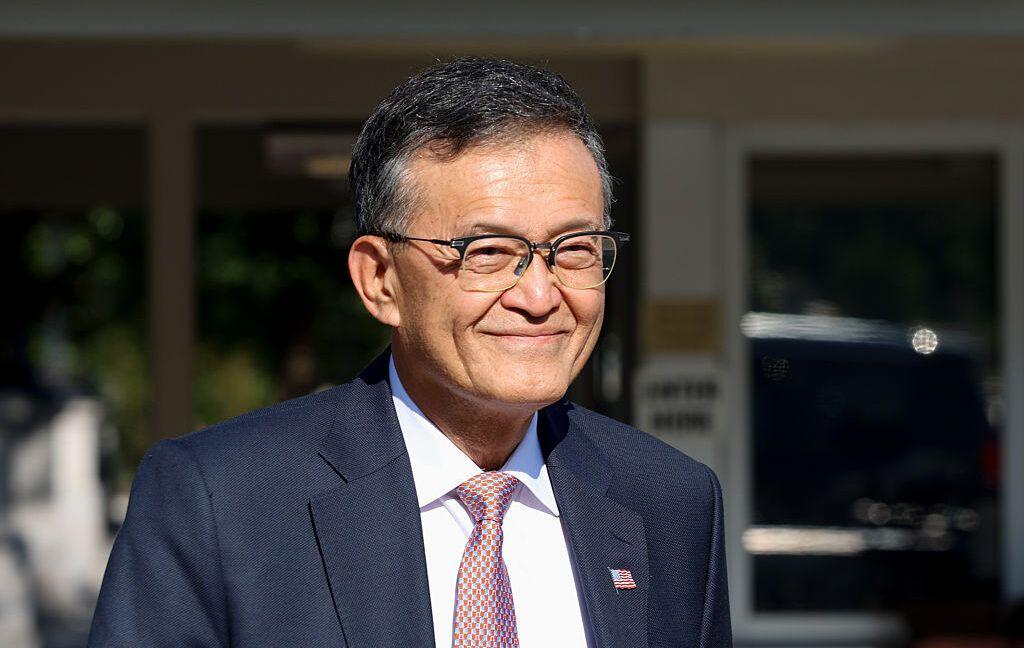

US may purchase stake in Intel after Trump attacked CEO

Donald Trump has been meddling with Intel, which now apparently includes mulling "the possibility of the US government taking a financial stake in the troubled chip maker," The Wall Street Journal reported. Trump and Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan weighed the option during a meeting on Monday at the White House, people familiar with the matter told WSJ. These talks have only just begun -- with Intel branding them a rumor -- and sources told the WSJ that Trump has yet to iron out how the potential arrangement might work. The WSJ's report comes after Trump called for Tan to "resign immediately" last week. Trump's demand was seemingly spurred by a letter that Republican senator Tom Cotton sent to Intel, accusing Tan of having "concerning" ties to the Chinese Communist Party. Cotton accused Tan of controlling "dozens of Chinese companies" and holding a stake in "hundreds of Chinese advanced-manufacturing and chip firms," at least eight of which "reportedly have ties to the Chinese People's Liberation Army." Further, before joining Intel, Tan was CEO of Cadence Design Systems, which recently "pleaded guilty to illegally selling its products to a Chinese military university and transferring its technology to an associated Chinese semiconductor company without obtaining license." "These illegal activities occurred under Mr. Tan's tenure," Cotton pointed out. He demanded answers by August 15 from Intel on whether they weighed Tan's alleged Cadence conflicts of interest against the company's requirements to comply with US national security laws after accepting $8 billion in CHIPS Act funding -- the largest granted during Joe Biden's term. The senator also asked Intel if Tan was required to make any divestments to meet CHIPS Act obligations and if Tan has ever disclosed any ties to the Chinese government to the US government. Neither Intel nor Cotton's office responded to Ars' request to comment on the letter or confirm whether Intel has responded. But Tan has claimed that there is "a lot of misinformation" about his career and portfolio, the South China Morning Post reported. Born in Malaysia, Tan has been a US citizen for 40 years after finishing postgraduate studies in nuclear engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In an op-ed, SCMP reporter Alex Lo suggested that Tan's investments -- which include stakes in China's largest sanctioned chipmaker, SMIC, as well as "several" companies on US trade blacklists, SCMP separately reported -- seem no different than other US executives and firms with substantial investments in Chinese firms. "Cotton accused [Tan] of having extensive investments in China," Lo wrote. "Well, name me a Wall Street or Silicon Valley titan in the past quarter of a century who didn't have investment or business in China. Elon Musk? Apple? BlackRock?" He also noted that "numerous news reports" indicated that "Cadence staff in China hid the dodgy sales from the company's compliance officers and bosses at the US headquarters," which Intel may explain to Cotton if a response comes later today. Any red flags that Intel's response may raise seems likely to heighten Trump's scrutiny, as he looks to make what Reuters reported was yet another "unprecedented intervention" by a president in a US firm's business. Previously, Trump surprised the tech industry by threatening the first-ever tariffs aimed at a US company (Apple) and more recently, Trump struck an unusual deal with Nvidia and AMD that gives US a 15 percent cut of the firms' revenue from China chip sales. However, Trump was seemingly impressed by Tan after some face-time this week. Trump came out of their meeting professing that Tan has an "amazing story," Bloomberg reported, noting that any agreement between Trump and Tan "would likely help Intel build out" its planned $28 billion chip complex in Ohio. Those chip fabs -- boosted by CHIPS Act funding -- were supposed to put Intel on track to launch operations by 2030, but delays have set that back by five years, Bloomberg reported. That almost certainly scrambles another timeline that Biden's Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo had suggested would ensure that "20 percent of the world's most advanced chips are made in the US by the end of the decade." Why Intel may be into Trump's deal At one point, Intel was the undisputed leader in chip manufacturing, Bloomberg noted, but its value plummeted from $288 billion in 2020 to $104 billion today. The chipmaker has been struggling for a while -- falling behind as Nvidia grew to dominate the AI chip industry -- and 2024 was its "first unprofitable year since 1986," Reuters reported. As the dismal year wound down, Intel's longtime CEO Pat Gelsinger retired. Helming Intel for more than 40 years, Gelsinger acknowledged the "challenging year." Now Tan is expected to turn it around. To do that, he may need to deprioritize the manufacturing process that Gelsinger pushed, which Tan suspects may have caused Intel being viewed as an outdated firm, anonymous insiders told Reuters. Sources suggest he's planning to pivot Intel to focus more on "a next-generation chipmaking process where Intel expects to have advantages over Taiwan's TSMC," which currently dominates chip manufacturing and even counts Intel as a customer, Reuters reported. As it stands now, TSMC "produces about a third of Intel's supply," SCMP reported. This pivot is supposedly how Tan expects Intel can eventually poach TSMC's biggest customers like Apple and Nvidia, Reuters noted. Intel has so far claimed that any discussions of Tan's supposed plans amount to nothing but speculation. But if Tan did go that route, one source told Reuters that Intel would likely have to take a write-off that industry analysts estimate could trigger losses "of hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars." Perhaps facing that hurdle, Tan might be open to agreeing to the US purchasing a financial stake in the company while he rights the ship. Trump/Intel deal reminiscent of TikTok deal Any deal would certainly deepen the government's involvement in the US chip industry, which is widely viewed as critical to US national security. While unusual, the deal does seem somewhat reminiscent to the TikTok buyout that the Trump administration has been trying to iron out since he took office. Through that deal, the US would acquire enough ownership divested from China-linked entities to supposedly appease national security concerns, but China has been hesitant to sign off on any of Trump's proposals so far. Last month, Trump admitted that he wasn't confident that he could sell China on the TikTok deal, which TikTok suggested would have resulted in a glitchier version of the app for American users. More recently, Trump's commerce secretary threatened to shut down TikTok if China refuses to approve the current version of the deal. Perhaps the terms of a US deal with Intel could require Tan to divest certain holdings that the US fears compromises the CEO. Under terms of the CHIPS Act grant, Intel is already required to be "a responsible steward of American taxpayer dollars and to comply with applicable security regulations," Cotton reminded the company in his letter. But social media users in Malaysia and Singapore have criticized Cotton of the "usual case of racism" in attacking Intel's CEO, SCMP reported. They noted that Cotton "was the same person who repeatedly accused TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew of ties with the Chinese Communist Party despite his insistence of being a Singaporean," SCMP reported. "Now it's the Intel's CEO's turn on the chopping block for being [ethnic] Chinese," a Facebook user, Michael Ong, said. Tensions were so high that there was even a social media push for Tan to "call on Trump's bluff and resign, saying 'Intel is the next Nokia' and that Chinese firms would gladly take him instead," SCMP reported. So far, Tan has not criticized the Trump administration for questioning his background, but he did issue a statement yesterday, seemingly appealing to Trump by emphasizing his US patriotism. "I love this country and am profoundly grateful for the opportunities it has given me," Tan said. "I also love this company. Leading Intel at this critical moment is not just a job -- it's a privilege." Trump's Intel attacks rooted in Biden beef? In his op-ed, SCMP's Lo suggested that "Intel itself makes a good punching bag" as the biggest recipient of CHIPS Act funding. The CHIPS Act was supposed to be Biden's lasting legacy in the US, and Trump has resolved to dismantle it, criticizing supposed handouts to tech firms that Trump prefers to strong-arm into US manufacturing instead through unpredictable tariff regimes. "The attack on Intel is also an attack on Trump's predecessor, Biden, whom he likes to blame for everything, even though the industrial policies of both administrations and their tech war against China are similar," Lo wrote. At least one lawmaker is ready to join critics who question if Trump's trade war is truly motivated by national security concerns. On Friday, US representative Raja Krishnamoorthi (D.-Ill.) sent a letter to Trump "expressing concern" over Trump allowing Nvidia to resume exports of its H20 chips to China. "Trump's reckless policy on AI chip exports sells out US security to Beijing," Krishnamoorthi warned. "Allowing even downgraded versions of cutting-edge AI hardware to flow" to the People's Republic of China (PRC) "risks accelerating Beijing's capabilities and eroding our technological edge," Krishnamoorthi wrote. Further, "the PRC can build the largest AI supercomputers in the world by purchasing a moderately larger number of downgraded Blackwell chips -- and achieve the same capability to train frontier AI models and deploy them at scale for national security purposes." Krishnamoorthi asked Trump to send responses by August 22 to four questions. Perhaps most urgently, he wants Trump to explain "what specific legal authority would allow the US government to "extract revenue sharing as a condition for the issuance of export licenses" and what exactly he intends to do with those funds. Trump was also asked to confirm if the president followed protocols established by Congress to ensure proper export licensing through the agreement. Finally, Krishnamoorthi demanded to know if Congress was ever "informed or consulted at any point during the negotiation or development of this reported revenue-sharing agreement with NVIDIA and AMD." "The American people deserve transparency," Krishnamoorthi wrote. "Our export control regime must be based on genuine security considerations, not creative taxation schemes disguised as national security policy."

[2]

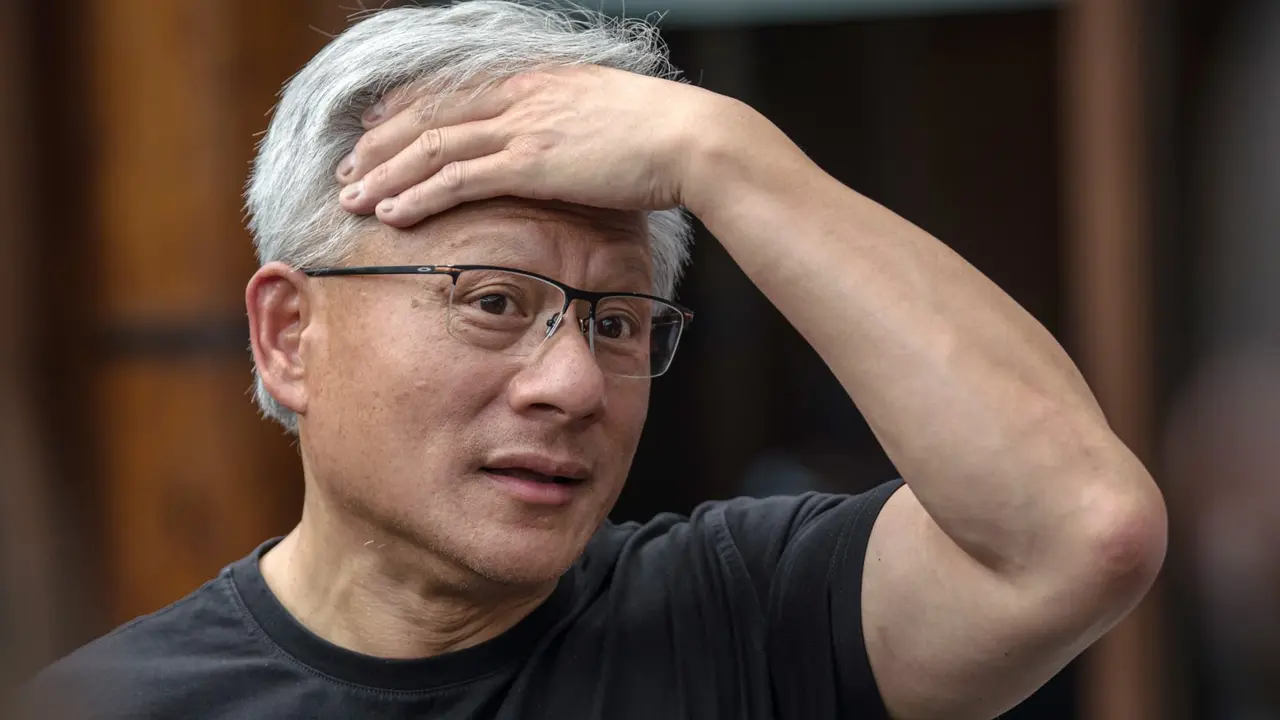

China isn't welcoming Nvidia back with open arms after Trump clears way for H20 exports

Beijing is signaling to its tech firms that they must continue to support local AI chip companies, experts say.Nvidia secured what was seen as a major win last month when the U.S. government announced it would allow it to resume sales of its made-for-China H20 chip. But it has since become clear that Beijing wont be rolling out the red carpet. Despite the U.S. softening on chip export controls -- which Beijing has long opposed -- Nvidia is being welcomed back under increased distrust and scrutiny. On Tuesday, Bloomberg reported that China had urged companies against using Nvidia's H20 chips, or those from Advanced Micro Devices , especially for government and national security use cases, citing sources familiar with the matter. In response to the report, Nvidia said in a statement that the H20 "is not a military product or for government infrastructure," and that banning the sale of H20 in China would only harm U.S. economic and technology leadership with zero national security benefit. In a separate report , The Information said regulators in China had gone so far as to order major tech companies, including ByteDance, Alibaba and Tencent, to suspend Nvidia chip purchases altogether until the completion of a national security review. "We're hearing that this is a hard mandate, and that [authorities are actually] stopping additional orders of H20s for some companies," Qingyuan Lin, a senior analyst covering China semiconductors at Bernstein, told CNBC. The news comes just weeks after Nvidia was summoned by Chinese officials over security concerns regarding potential tracking technology and "backdoors" in their chips. It also throws a wrench into Nvidia's plans to maintain market share in China, as CEO Jensen Huang tries to navigate his business through increasing tensions and shifting trade policy between the U.S. and China. Beijing's probe into Nvidia comes after the House and Senate proposed laws that would require semiconductor companies like Nvidia to include security mechanisms and location verification in their advanced artificial intelligence chips. Nvidia has denied that any such "backdoors" that provide remote access or control exist. According to chip industry analysts, however, the actions against Nvidia also highlight that Beijing remains steadfast in chip self-sufficiency campaigns and is likely to resist the Trump administration's plan to keep American AI hardware dominant in China. "It is signaling to Chinese tech firms that they must continue to support Huawei's AI development, even if Nvidia's chips are better," Chris Miller, author of "Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology," told CNBC. Building its domestic supply chain China has long had the desire to build up a self-reliant chip supply chain, and many experts say those efforts have been accelerating since chip export restrictions first took effect in October 2022. While China's domestic GPU (graphics processing unit) companies remain behind Nvidia in both scale and advancement, they have been beneficiaries of massive state funding and restrictions on Nvidia's most advanced chips. Reva Goujon, a director at Rhodium Group, told CNBC that Beijing appears to be trying to tackle constraints to the local adoption of Chinese-made chips -- based on regulators' questions about the H20s that were posed to local AI developers. Although that remains a serious challenge, "it's even more top of mind now that you have U.S. Cabinet officials openly broadcasting a strategy to get China more addicted to U.S. technologies," she added. When the resumption of H20 exports was first announced in July, a Trump administration official had presented the policy as a trade concession. However, in following weeks, the administration has indicated that the move is also part of a strategy to keep China's AI built on U.S. technology. Trump is also working on a deal that's expected to see Washington take a 15% cut of Nvidia's business in China. Not an all-out ban Still, despite Beijing's show of resistance to the H20s, experts doubt that Beijing will block their imports in a meaningful way, at least for now. "It's not likely the Chinese government will maintain a ban. After the investigation is finished, I don't think it has a strong rationale to actually block the H20s," said Bernstein's Lin. However, he added that it's unclear how long the investigation will last, and that delays to the H20's return could create more room for local players as AI companies search for alternatives. Companies such as Huawei are designing their own GPUs for the China market. Ray Wang, research director for semiconductors, supply chain and emerging technology at Futurum Group, said recent moves by Beijing are likely meant to send a message that the H20s present a potential security concern, and the government will be monitoring their use very closely. "This could impact some customers' long-term purchasing decisions," he added. In the meantime, assuming the H20 chips are allowed back in the market, they are expected to benefit local AI developers as they wait for the domestic industry to continue to advance. "There is meaningful demand for the H20 in China today," semiconductor research and consulting firm SemiAnalysis said in a note on Tuesday. Huawei, despite an aggressive boost to production, is still unable to meet all of China's inference demand, they added. While China has been making big strides in chip design, its supply of advanced GPUs remains constrained by existing export controls on the world's most advanced chipmaking equipment. "Access to US technology can still be valuable when Chinese AI developers and chipmakers are experiencing these growing pains under compute constraints, but Beijing wants to ensure the roadmap is still driving toward self-reliance in the end," said Rhodium's Goujon. Meanwhile, there are signs that Washington may take more steps to keep U.S. chips dominant in the Chinese market. On Tuesday, Trump said he was open to extending the chip approvals to companies aside from Nvidia and AMD. He also signaled he would allow Nvidia to sell a less powerful version of its latest Blackwell chip to China.

[3]

Trump hiked tariffs on US imports. Now he's looking at exports - sparking fears of 'dangerous precedent'

Experts warn of destabilized trading relations after White House strikes deal with Nvidia to take a 15% cut of certain AI chip sales to Chinese companies Apple CEO Tim Cook visited the White House bearing an unusual gift. "This box was made in California," Cook reassured his audience in the Oval Office this month, as he took off the lid. Inside was a glass plaque, engraved for its recipient, and a slab for the plaque to sit on. "The base was made in Utah, and is 24-karat gold," said Cook. Donald Trump appeared genuinely touched by the gift. But the plaque wasn't Cook's only offering: Apple announced that day it would invest another $100bn in US manufacturing. The timing appeared to work well for Apple. That day, Trump said Apple would be among the companies that would be exempt from a new US tariff on imported computer chips. The Art of the Deal looms large in the White House, where Trump is brokering agreements with powerful tech companies - in the midst of his trade war - that are reminiscent of the real estate transactions that launched him into fame. But in recent days, this dealmaking has entered uncharted waters. Two days after Cook and Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang had a closed-door meeting with Trump at the White House. The president later announced Nvidia, along with its rival Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), will be allowed to sell certain artificial intelligence chips to Chinese companies - so long as they share 15% of their revenue with the US government. It was a dramatic about-face from Trump, who initially blocked the chips' exports in April. And it swiftly prompted suggestions that Nvidia was buying its way out of simmering tensions between Washington and Beijing. Trade experts say such a deal, where a company essentially pays the US government to export a good, could destabilize trading relations. Martin Chorzempa, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said that it creates "the perception that export controls are up for sale". "If you create the perception that licenses, which are supposed to be determined on pure national security grounds, are up for sale, you potentially open up room for there to be this wave of lobbying for all sorts of really, dangerous, sensitive technologies," Chorzempa said. "I think that's a very dangerous precedent to set." Though the White House announced the deal, it technically hasn't been rolled out yet, likely because of legal complications. The White House is calling the deal a "revenue-sharing" agreement, but critics point out that it could also be considered a tax on exports, which may not be legal under US laws or the constitution. The "legality" of the deal was "still being ironed out by the Department of Commerce", White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt told reporters this week. Nvidia and AMD's AI chips are at the heart of the technological arms race between the US and China. Nvidia, which became the first publicly traded company to reach a $4tn valuation last month, creates the essential processing chips that are used to run and develop AI. The US government has played a role in this arms race over the last several years, setting regulations on what AI chips and manufacturing equipment can be sent to China. If China has less computing power, the country will be slower to develop AI, giving a clear advantage to the US. But despite the restrictions, China has been catching up, raising questions on how US policy should move forward. "They haven't held them back as far as the advocates had hoped. The US has an enormous computing advantage over China, but their best models are only a few months behind our best models," Chorzempa said. For US policymakers, "the question they've had to grapple with is: Where do you draw the line?" The AI chips Nvidia and AMD can now sell to China aren't considered high-end. While they can be used for inference on trained models, they aren't powerful enough to train new AI models. When announcing the deal with Nvidia and AMD, Trump said the chip is "an old chip that China already possesses ... under a different label". This is where a major debate on AI policy comes in. Those who take a hardline stance on the US's relationship with China say that allowing Chinese companies to purchase even an "old chip" could still help the country get an advantage over the US. Others would say a restriction on such chips wouldn't be meaningful, and could even be counterproductive. To balance these two sides, the Trump administration is asking companies to pay up in order to export to China - a solution that people on both sides of the AI debate say is a precarious one. "Export controls are a frontline defense in protecting our national security, and we should not set a precedent that incentivizes the government to grant licenses to sell China technology that will enhance AI capabilities," said John Moolenaar, a Republican US representative from Michigan, in a statement. But Trump's gut-reaction to dealmaking seems focused on the wallet. On Wednesday, US treasury secretary Scott Bessent praised the arrangement and suggested it could be extended to other industries over time. "I think that right now this is unique, but now that we have the model and the beta test, why not expand it?" he told Bloomberg. Julia Powles, executive director of the Institute for Technology, Law and Policy at the University of California, Los Angeles, said the deal opens up questions of whether similar pressure can be applied to other tech companies. "What other quid pro quo might be asked in the future? The quid pro quo that would be of great concern to the [tech] sector is anything that reduces their reputation for privacy and security," Powles said. "That's thinking of government like a transactional operator, not like an institution with rules about when, how and for what it can extract taxes, levies and subsidies." But that seems to be how the White House runs now. When explaining to the press how he made the deal, Trump said he told Huang: "I want 20% if I'm going to approve this for you". "For the country, for our country. I don't want it myself," the president added. "And he said, 'Would you make it 15?' So we negotiated a little deal."

[4]

Trump's unprecedented, potentially unconstitutional deal with Nvidia and AMD, explained: Alexander Hamilton would approve

The chips do appear to be quite significant to China, considering that the Cyberspace Administration of China held discussions with Nvidia over security concerns that the H20 chips may be tracked and turned off remotely, according to a disclosure on its website. The deal, which lifted an export ban on Nvidia's H20 AI chips and AMD's MI308, and followed heated negotiations, was widely described as unusual and also still theoretical at this point, with the legal details still being ironed out by the Department of Commerce. Legal experts have questioned whether the eventual deal would constitute an unconstitutional export tax, as the U.S. Constitution prohibits duties on exports. This has come to be known as the "export clause" of the constitution. Indeed, it's hard to find much precedent for it anywhere in the history of the U.S. government's dealings with the corporate sector. Erik Jensen, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University who has studied the history of the export clause, told Fortune he was not aware of anything like this in history. In the 1990s, he added, the Supreme Court struck down two attempted taxes on export clause grounds (cases known as IBM and U.S. Shoe). Jensen said tax practitioners were surprised that the court took up the cases: "if only because most pay no attention to constitutional limitations, and the Court hadn't heard any export clause cases in about 70 years." The takeaway was clear, Jensen said: "The export clause matters." Columbia University professor Eric Talley agreed with Jensen, telling Fortune that while the federal government has previously applied subsidies to exports, he's not aware of other historical cases imposing taxes on selected exporters. Talley also cited the export clause as the usual grounds for finding such arrangements unconstitutional. Rather than downplaying the uniqueness of the arrangement, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has been leaning into it. In a Bloomberg television interview, he said: "I think you know, right now, this is unique. But now that we have the model and the beta test, why not expand it? I think we could see it in other industries over time." Bessent and the White House insist there are "no national security concerns," since only less-advanced chips are being sold to China. Instead, officials have touted the deal as a creative solution to balance trade, technology, and national policy. The arrangement has drawn sharp reaction from business leaders, legal experts, and trade analysts. Julia Powles, director of UCLA's Institute for Technology, Law & Policy, told the Los Angeles Times: "It ties the fate of this chip manufacturer in a very particular way to this administration, which is quite rare." Experts warned that if replicated, this template could pressure other firms -- not just tech giants -- into similar arrangements with the government. Already, several unprecedented arrangements have been struck between the Trump administration and the corporate sector, ranging from the "golden share" in U.S. Steel negotiated as part of its takeover by Japan's Nippon Steel to the federal government reportedly discussing buying a stake in chipmaker Intel. Nvidia and AMD have declined to comment on specifics. When contacted by Fortune for comment, Nvidia reiterated its statement that it follows rules the U.S. government sets for its participation in worldwide markets. "While we haven't shipped H20 to China for months, we hope export control rules will let America compete in China and worldwide. America cannot repeat 5G and lose telecommunication leadership. America's AI tech stack can be the world's standard if we race." The White House declined to comment about the potential deal. AMD did not respond to a request for comment. While Washington has often intervened in business -- especially in times of crisis -- the mechanism and magnitude of the Nvidia/AMD deal are virtually unprecedented in recent history. The federal government appears to have never previously claimed a percentage of corporate revenue from export sales as a precondition for market access. Instead, previous actions took the form of temporary nationalization, regulatory control, subsidies, or bailouts -- often during war or economic emergency. Examples of this include the seizure of coal mines (1946) and steel mills (1952) during labor strikes, as well as the 2008 financial crisis bailouts, where the government took equity stakes in large corporations including two of Detroit's Big three and most of Wall Street's key banks. During World War I, the War Industries Board regulated prices, production, and business conduct for the war effort. Congress has previously created export incentives and tax-deferral strategies (such as the Domestic International Sales Corporation and Foreign Sales Corporation Acts), but these measures incentivized sales rather than directly diverting a fixed share of export revenue to the government. Legal scholars stress that such arrangements were subjected to global trade rules and later modified after international complaints. The U.S. prohibition on export taxes dates back to the birth of the nation. Case Western's Jensen has written that some delegates of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, such as New York's Alexander Hamilton, were in favor of the government being able to tax revenue sources such as imports and exports, but the "staple states" in the southern U.S. were fiercely opposed, given their agricultural bent, especially the importance of cotton at that point. Still, many other countries currently have export taxes on the books, though they are generally imposed across all exporters, rather than as one-off arrangements that remove barriers to a specific market. And many of the nations with export taxes are developing countries who tax agricultural or resource commodities. In several cases (Uganda, Malaya, Sudan, Nigeria, Haiti, Thailand), export taxes made up 10% to 40% of total government tax revenue in the 1960s and 1970s, according to an IMF staff paper. Globally, most countries tax profits generated within their borders ("source-based corporate taxes"), but rarely as a direct percentage of export sales as a market access precondition. The standard model is taxation of locally earned profits, regardless of export destination; licensing fees and tariffs may be applied, but not usually as a fixed percent of export revenue as a pre-negotiated entry fee. Although the Nvidia/AMD deal doesn't take the usual form of a tax, Case Western's Jensen added. "I don't see what else it could be characterized as." It's clearly not a "user fee," which he said is the usual triable issue of law in export clause cases. For instance, if goods or services are being provided by the government in exchange for the charge, such as docking fees at a governmentally operated port, then that charge isn't a tax or duty and the Export Clause is irrelevant. "I just don't see how the charges that will be levied in the chip cases could possibly be characterized in that way." Players have been known to "game" the different legal treatments of subsidies and taxes, Columbia's Talley added. He cited the example of a government imposing a uniform, across-the-board tax on all producers, but then providing a subsidy to sellers who sell to domestic markets. "The net effect would be the same as a tax on exports, but indirectly." He was unaware of this happening in the U.S. but cited several international examples including Argentina, India, and even the EU. One famous example of a canny international tax strategy was Apple's domicile in Ireland, along with so many other multinationals keeping their international profits offshore in affiliates in order to avoid paying U.S. tax, which at the time applied to all worldwide income upon repatriation. Talley said much of this went away after the 2018 tax reforms, which moved the U.S. away from a worldwide corporate tax, with some exceptions. If Trump's chip export tax is an anomaly in the annals of U.S. international trade, the deal structure has some parallels in another corner of the business world: organized crime, where "protection rackets" have a long history. Businesses bound by such deals must pay a cut of their revenues to a criminal organization (or parallel government), effectively as the cost for being allowed to operate or to avoid harm. The China chip export tax and the protection rackets extract revenue as a condition for market access, use the threat of exclusion or punishment for non-payment, and both may be justified as "protection" or "guaranteed access," but are not freely negotiated by the business. "It certainly has the smell of a governmental shakedown in certain respects," Columbia's Talley told Fortune, considering that the "underlying threat was an outright export ban, which makes a 15% surcharge seem palatable by comparison." Talley noted some nuances, such as the generally established broad statutory and constitutional support for national-security-based export bans on various goods and services sold to enumerated countries, which have been imposed with legal authority on China, North Korea, Iraq, Russia, Cuba, and others. "From an economic perspective, a ban on an exported good is tantamount to a tax of 'infinity percent' on the good," Talley said, meaning it effectively shuts down the export market for that good. "Viewed in that light, a 15% levy is less (and not more) extreme than a ban." Still, there's the matter, similar to Trump's tariff regime, of making a legal challenge to an ostensibly blatantly illegal policy actually hold up in court. "A serious question with the chips tax," Case Western's Jensen told Fortune, "is who, if anyone, would have standing to challenge the tax?" In other words, it may be unconstitutional, but who's actually going to compel the federal government to obey the constitution?

[5]

Nvidia and AMD's 'special treatment' from Trump shakes up an already tangled global chip supply chain

Donald Trump's decision to let Nvidia and AMD export AI processors to China in exchange for a cut of their sales will have repercussions far beyond the U.S. The semiconductor supply chain is global, involving a wide array of non-U.S. companies, often based in countries that are U.S. allies. Nvidia's chips may be designed and sold by a U.S. company, but they're manufactured by Taiwan's TSMC, using chipmaking tools from companies like ASML, which is based in the Netherlands, and Japan's Tokyo Election, and using components from suppliers like South Korea's SK Hynix. The U.S. leaned on these global companies for years to try to limit their engagement with China; these efforts picked up after the passage of the CHIPS Act and the expansion of U.S. chip-export controls in 2022. Washington has also pressured major transshipment hubs, like Singapore and the United Arab Emirates, to more closely monitor chip shipments to ensure that controlled chips don't make their way to China in violation of U.S. law. Within the U.S., discussion of Trump's Nvidia deal has focused on what it means for China's government's and Chinese companies' ability to get their hands on cutting-edge U.S. technology. But several other countries and companies are likely studying the deal closely to see if they might get an opening to sell to China as well. Trump's Nvidia deal "tells you that [U.S.] national security is not really the issue, or has never been the issue" with export controls, says Mario Morales, who leads market research firm IDC's work on semiconductors. Companies and countries will "probably have to revisit what their strategy has been, and in some cases, they're going to break away from the U.S. administration's policies." "If Nvidia and AMD are given special treatment because they've 'paid to play', why shouldn't other companies be doing the same?" he adds. The Biden administration spent a lot of diplomatic energy to get its allies to agree to limit their semiconductor exports to China. First, Washington said that manufacturers like TSMC and Intel that wanted to tap billions in subsidies could not expand advanced chip production in China. Then, the U.S. pushed for its allies to impose their own sanctions on exports to China. "Export controls and other sanctions efforts are necessarily multilateral, yet are fraught with collective action problems," says Jennifer Lind, an associate professor at Dartmouth College and international relations expert. "Other countries are often deeply unenthusiastic about telling their firms -- which are positioned to bring in a lot of revenue, which they use for future innovation -- that they cannot export to Country X or Country Y." This translates to "refusing to participate in export controls or to devoting little or no effort to ensuring that their firms are adhering to the controls," she says. Paul Triolo, a partner at the DGA-Albright Stonebridge Group, points out that "Japanese and Dutch officials during the Biden administration resisted any serious alignment with U.S. controls," and suggests that U.S allies "will be glad to see a major stepping back from controls." Ongoing trade negotiations between the U.S. and its trading partners could weaken export controls further. Chinese officials may demand a rollback of chip sanctions as part of a grand bargain between Washington and Beijing, similar to how the U.S. agreed to grant export licenses to Nvidia and AMD in exchange for China loosening its controls on rare earth magnets. Japan and South Korea may also bring up the chip controls as part of their own trade negotiations with Trump. A separate issue are controls over the transfer of Nvidia GPUs. The U.S. has leaned on governments like Singapore, Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates to prevent advanced Nvidia processors from making their way to China. Scrutiny picked up in the wake of DeepSeek's surprise AI release earlier this year, amid allegations that the Hangzhou-based startup had trained its powerful models on Nvidia processors that were subject to export controls. (The startup claims that it acquired its processors before export controls came into effect). As of now, the two chips allowed to be sold in China-Nvidia's H20 and AMD's MI308-are not the most powerful AI chips on the market. The leading-edge processors, like Nvidia's Blackwell chip, cannot be sold to China. That means chip smuggling will continue to be a concern for the U.S. government. Yet "enforcement will be spotty," Triolo says. "The Commerce Department lacks resources to track GPUs globally, hence expect continuing diversions of limited amounts of GPUs to China via Thailand, Malaysia, and other jurisdictions." Triolo is, instead, focused on another loophole in the export control regime: Chinese firms accessing AI chips based in overseas data centers. "There is no sign that the Trump Commerce Department is gearing up to try and close this gaping loophole in U.S. efforts to limit Chinese access to advanced compute," he says. Not all analysts think we'll see a complete unraveling of the export control regime. "The controls involve a complex multinational coalition that all parties will be hesitant to disrupt, given how uncertain the results will be," says Chris Miller, author of Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology. He adds that many of these chipmakers and suppliers don't have the same political heft as Nvidia, the world's most valuable company. Yet while these companies may not be as politically savvy as Nvidia, they're just as important. TSMC, for example, is the only company that can manufacture the newest generation of advanced chips; ASML is the only supplier of the extreme ultraviolet lithography machines used to make the smallest semiconductors. "I don't believe it's leverage that the Trump administration will easily give away," says Ray Wang, a semiconductor researcher at the Futurum Group.

[6]

The Nvidia chip deal that has Trump officials threatening to quit

Dylan Matthews is a senior correspondent and head writer for Vox's Future Perfect section and has worked at Vox since 2014. He is particularly interested in global health and pandemic prevention, anti-poverty efforts, economic policy and theory, and conflicts about the right way to do philanthropy. Whatever else can be said about the second Trump administration, it is always teaching me about parts of the Constitution I had forgotten were even in there. Case in point: Article I, Section 9, Clause 5 states that "No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State." This is known as the export clause, not to be confused with the import-export clause (Article I, Section 10, Clause 2). The Supreme Court has repeatedly held, most recently in 1996's US v. IBM, that this clause bans Congress and the states from imposing taxes on goods exported from one state to another or from the US to foreign countries. I found myself reading US v. IBM after President Donald Trump announced an innovative new deal with chipmakers Nvidia and AMD. They can now export certain previously restricted chips to China but have to pay a 15 percent tax to the federal government on the proceeds. Now, I'm not a lawyer, but several people who are lawyers, like former National Security Council official Peter Harrell, immediately interpreted this as a clearly unconstitutional export tax (and as illegal under the 2018 Export Control Reform Act, to boot). At this point, there's something kind of sad and impotent about complaining that something Trump is doing is illegal and unconstitutional. It feels like yelling at the refs that the Harlem Globetrotters aren't playing fair; of course they aren't, no one cares. The refs are unlikely to step in here, either. The parties with the standing to sue and block the export taxes are Nvidia and AMD, and they've already agreed to go along with it. Maybe the best we can do is understand why this happened and what it means for the future of AI. While AMD is included in the deal, for all practical purposes, the AI chips in question are being made by Nvidia -- and the main one in question is the H20. As I explained last month, the H20 is entirely the product of US export controls meant to limit export of excessively powerful chips to China. Nvidia took its flagship H100 chip, widely used for AI training, and dialed its processing power (as measured in floating point operations per second) way down, thus satisfying rules restricting advanced chips that the Biden administration put in place and Trump has maintained. At the same time, it dialed up the memory bandwidth (or the rate at which data moves between the chip and system memory) past even H100's levels. That makes the H20 better than the H100 at answering queries to AI models in action, even if it's worse at training those models to start with. Critics saw this all as an attempt to obey the letter of the export controls while violating their spirit. It still meant Nvidia was exporting very useful, powerful chips to Chinese AI firms, which could use those to catch up with or leap ahead of US firms -- precisely what the Biden administration was trying to prevent. In April, the Trump administration seemed to agree when it sent Nvidia a letter informing it that it would not receive export licenses for shipping H20s to China. Then, in July, reportedly after both some bargaining with China over rare earth metals and a personal entreaty from Nvidia founder and CEO Jensen Huang, Trump flip-flopped; the chips could go to China after all. The only thing new this month is that he wants to get a cut of the proceeds. That, of course, is an important new element, not least because it seems bad that the president is asserting the power to unilaterally impose new taxes without Congress. (At least with tariffs, Trump has some laws Congress passed he can cite theoretically granting the authority.) But the big question about H20s remains the same: Does this help Chinese companies like DeepSeek catch up with US companies like OpenAI? And how bad is that, if it happens? The concerns here are such that maybe the best way to understand them is to imagine a debate between a pro-export and anti-export advocate. I'm taking some poetic license here, in part because people in the sector are often averse to plainly saying what they mean on the record. But I think it's a fair reflection of the debate as I've heard it. Anti-Export Guy: Trump says he wants the US to have "global dominance" in AI, and here he is, just letting China have very powerful chips. This obviously hurts the US's edge. Pro-Export Guy: Does it? Again, the H20 is powerful, but it's no H100. In any case, Chinese firms are totally allowed to rent out advanced AI chips in US-based cloud servers. DeepSeek could even rent time on an H100 that way. So, why are we freaking out about exporting a weaker chip? Anti-Export: You act like the cloud option is a loophole -- it's a feature! That way, they're dependent on US servers and companies. If Chinese AI firms ever start making dangerous systems, the US can shut off their access, and they'll be out of luck. Pro-Export: Again, will they be out of luck? There's a third option after Nvidia exports and US servers. Huawei is making its own AI-optimized chips. Chinese firms don't want to depend on foreign servers forever, and if we deny them Nvidia chips, they'll run right over to Huawei chips. Anti-Export: Saying you don't need Nvidia chips when you have Huawei chips is like if you told someone 20 years ago that they don't need an iPod because they have a Zune. Yes, Huawei chips exist, but they're so much worse. They're lower bandwidth than H20s, Huawei's software libraries are full of bugs, and the chips sometimes dangerously overheat. Pro-Export: You're exaggerating. By some metrics, Huawei's latest systems (not just the chips, but the surrounding servers) outperform Nvidia's top-end model -- even though that model uses B200s that are faster than H100s and lightyears faster than you'd ever be allowed to export to China. Yes, programmers will have to learn Huawei's libraries, and transitioning from Nvidia's will take time, but it's doable. Google, Anthropic, and OpenAI have all recently moved away from Nvidia chips toward things like Google's own TPUs or Amazon's Trainiums. That took effort, but they did it. Anti-Export: Sure, but those companies still use Nvidia's too. OpenAI wants 100,000 chips in one Norwegian facility alone. And while US companies may be trying out the competition, Chinese companies still vastly prefer Nvidia to Huawei. DeepSeek reportedly had to delay its latest model because it tried to train it on Huawei chips but couldn't. Even if Huawei chips were popular, Huawei lacks the production capacity to meet demand. It relies on smuggled components to make its top-end chips and can make at most 200,000 this year, compared to the roughly 10 million Nvidia chips shipped annually. There's no substitute for Nvidias. I suppose we'll see, in the next few months and in the rollout of new chips from competitors like Huawei, who got the better of that argument. China is reportedly discouraging firms from using Nvidia chips in the wake of the export tax deal, largely to encourage them to use domestic chips like Huawei, though they are clearly not banning the firms from using Nvidias if they prove necessary. It's also investigating whether the US is including spyware in them. The bigger question this debate raises for me, and one I certainly can't answer adequately here, is: To what degree is "beating China" on AI important for making the future of AI go well? The answer for most US policymakers, and most people I know in the AI safety world, has been "very." The Financial Times reports that some Trump officials are considering resigning in protest over allowing China to get H20s. As Leopold Aschenbrenner, the AI analyst turned hedge funder, put it bluntly in his influential 2024 essay "Situational Awareness": "Superintelligence will give those who wield it the power to crush opposition, dissent, and lock in their grand plan for humanity." If China "wins," then, the result for humanity is permanent authoritarian repression. No doubt, the Beijing regime is brutal, and I have no faith that they will use AI wisely. I'm very confident they'll wield it to oppress Chinese citizens. But it feels as though "staying ahead of China" has become the sine qua non of US AI policy. I worry less that this focus on China is directionally wrong and more that it is exaggerated. The bigger danger is that no one can control these systems, rather than that China can, and that the focus on staying ahead of China will cause the US to speed deployment of automated weapons systems that could prove deeply destabilizing and dangerous. As with most aspects of AI, I feel like there's a small island of things we're all sure of and a vast ocean of unknowns. I think offering China H20s probably hurts AI safety a bit. I think.

Share

Share

Copy Link

The Trump administration strikes an unprecedented deal allowing Nvidia and AMD to sell AI chips to China in exchange for revenue sharing, sparking debates on legality and global trade implications.

Trump Administration's Unprecedented AI Chip Deal

In a surprising turn of events, the Trump administration has brokered an unconventional deal with tech giants Nvidia and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), allowing them to resume sales of certain artificial intelligence chips to Chinese companies. This arrangement, however, comes with a significant caveat: the companies must share 15% of their revenue from these sales with the U.S. government

1

2

.

Source: CNBC

The Deal's Implications and Controversies

This unprecedented move has sparked intense debate among experts, policymakers, and industry leaders. The deal represents a dramatic shift from the administration's previous stance, which had blocked the export of these chips to China in April

3

. Critics argue that this arrangement could set a dangerous precedent, potentially destabilizing trading relations and undermining the integrity of export controls.Martin Chorzempa, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, warned that this deal creates "the perception that export controls are up for sale," which could lead to a wave of lobbying for sensitive technologies

3

. The legality of the arrangement is also under scrutiny, with some experts questioning whether it constitutes an unconstitutional export tax4

.Global Repercussions and Supply Chain Impact

The deal's implications extend far beyond U.S. borders, affecting the intricate global semiconductor supply chain. While Nvidia and AMD are U.S. companies, their chips rely on components and manufacturing processes involving firms from Taiwan, the Netherlands, Japan, and South Korea

5

. This interconnectedness raises questions about how other countries and companies might respond to this new paradigm.Paul Triolo, a partner at the DGA-Albright Stonebridge Group, suggests that U.S. allies "will be glad to see a major stepping back from controls"

5

. This sentiment could potentially lead to a weakening of the multilateral export control regime that the U.S. has worked to establish.China's Response and Market Dynamics

Source: Fortune

Despite the U.S. government's apparent concession, China's response has been cautious. Reports indicate that Beijing has urged its tech companies against using Nvidia's H20 chips, especially for government and national security applications

2

. This stance underscores China's commitment to developing its domestic chip industry and reducing reliance on U.S. technology.Related Stories

The Broader Context of U.S.-China Tech Relations

This deal comes amid ongoing tensions between the U.S. and China in the tech sector. It follows other controversial moves by the Trump administration, including potential government stakes in companies like Intel

1

. The administration frames this as a strategy to maintain U.S. dominance in AI technology while extracting economic benefits.

Source: Ars Technica

Future Implications and Industry Reactions

The semiconductor industry and policymakers are closely watching how this deal unfolds. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has suggested that this model could be expanded to other industries

4

, raising concerns about the long-term implications for U.S. trade policy and corporate autonomy.As the global tech landscape continues to evolve, this unprecedented deal may mark a significant shift in how governments approach technology exports and international competition in critical sectors like artificial intelligence.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

[3]

Related Stories

U.S. Imposes 15% Revenue Share on Nvidia and AMD's AI Chip Sales to China Amid Escalating Tech Rivalry

05 Aug 2025•Policy and Regulation

Nvidia's H20 Chip Caught in US-China AI Trade Tensions

10 Aug 2025•Technology

Nvidia and AMD to Pay 15% of China AI Chip Sales Revenue to US Government

04 Aug 2025•Business and Economy

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens to cut Anthropic's $200M contract over AI safety restrictions in military ops

Policy and Regulation

2

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI closes in on $100 billion funding round with $850 billion valuation as spending plans shift

Business and Economy