SpaceX files plan for 1 million satellites as orbital AI data centers, but experts warn of major hurdles

2 Sources

2 Sources

[1]

Orbital AI data centers could work, but they might ruin Earth in the process

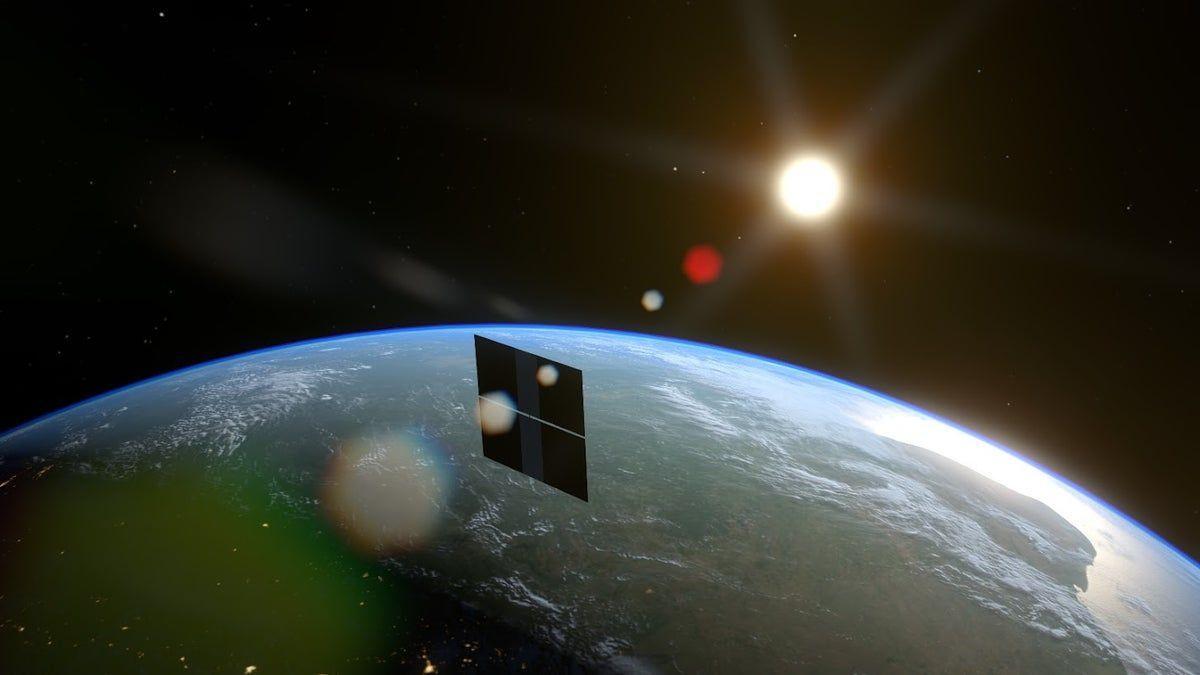

At the start of the month, Elon Musk announced that two of his companies -- SpaceX and xAI -- were merging, and would jointly launch a constellation of 1 million satellites to operate as orbital data centers. Musk's reputation might suggest otherwise, but according to experts, such a plan isn't a complete fantasy. However, if executed at the scale suggested, some of them believe it would have devastating effects on the environment and the sustainability of low Earth Earth orbit. Musk and others argue that putting data centers in space is practical given how much more efficient solar panels are away from Earth's atmosphere. In space, there are no clouds or weather events to obscure the sun, and in the correct orbit, solar panels can collect sunlight through much of the day. In combination with declining rocket launch costs and the price of powering AI data centers on Earth, Musk has said that within three years space will be the cheapest way to generate AI compute power. Ahead of the billionaire's announcement, SpaceX filed an eight-page application with the Federal Communications Commission detailing his plan. The company hopes to deposit the satellites in this massive cluster in altitudes ranging between 500km and 2000km. They would communicate with one another and SpaceX's Starlink constellation using laser "optical links." Those Starlink satellites would then transmit inference requests to and from Earth. To power the entire effort, SpaceX has proposed putting the new constellation in sun-synchronous orbit, meaning the spacecraft would fly along the dividing line that separates the day and night sides of the planet. Almost immediately the plan was greeted with skepticism. How would SpaceX, for instance, cool millions of GPUs in space? At first glance, that might seem like a weird point to get hung up on -- much of space being around -450 Fahrenheit -- but the reality is more complicated. In the near vacuum of space, the only way to dissipate heat is to slowly radiate it out, and in direct sunlight, objects can easily overheat. As one commenter on Hacker News succinctly put it, "a satellite is, if nothing else, a fantastic thermos." Scott Manley, who, before he created one of the most popular space-focused channels on YouTube, was a software engineer and studied computational physics and astronomy, argues SpaceX has already solved that problem at a smaller scale with Starlink. He points to the company's latest V3 model, which has about 30 square meters of solar panels. "They have a bunch of electronics in the middle, which are taking that power and doing stuff with it. Now, some of that power is being beamed away as radio waves, but there's a lot of thermal power that's being generated and then having to be dissipated. So they already have a platform that's running electronics off of power, and so it's not a massive leap to turn into something doing compute." Kevin Hicks, a former NASA systems engineer who worked on the Curiosity rover mission, is more skeptical. "Satellites with the primary goal of processing large amounts of compute requests would generate more heat than pretty much any other type of satellite," he said. "Cooling them is another aspect of the design which is theoretically possible but would require a ton of extra work and complexity, and I have doubts about the durability of such a cooling system." What about radiation then? There's a reason NASA relies on ancient hardware like the PowerPC 750 CPU found inside the Perseverance rover: Older chips feature larger transistors, making them more resilient to bit flips -- errors in processing caused most often by cosmic radiation -- that might scramble a computation. "Binary ones and zeroes are about the presence or absence of electrons, and the amount of charge required to represent a 'one' goes down as the transistors get smaller and smaller," explains Benjamin Lee, professor of computer and information science at the University of Pennsylvania. Space is full of energized particles traveling at incredible velocities, and the latest GPUs are built on the smallest, most advanced processing nodes to create transistor-dense silicon. Not a great combination. "My concern about radiation is that we don't know how many bit flips will occur when you deploy the most advanced chips and hundreds of gigabytes of memory up there," said Professor Lee, pointing to preliminary research by Google on the subject. As part of Project Suncatcher, its own effort to explore the viability of space-based data centers, the company put one of its Trillium TPUs in front of a proton beam to bombard it with radiation. It found the silicon was "surprisingly radiation-hard for space applications." While those results were promising, Professor Lee points out we just don't know how resilient GPUs are to radiation at this scale. "Even though modern computer architectures can detect and sometimes correct for those errors, having to do that again and again will slow down or add overhead to space-based computation," he said. Space engineer Andrew McCalip, who's done a deep dive on the economics of orbital data centers, is more optimistic, pointing to the natural resilience of AI models. "They don't require 100 percent perfect error-free runs. They're inherently very noisy, very stochastic," he explains, adding that part of the training for modern AI systems involves "injecting random noise into different layers." Even if SpaceX could harden its GPUs against radiation, the company would still lose satellites to GPUs that break down. If you know anything about data centers here on Earth, it's that they require constant maintenance. Components like SSDs and GPUs die all the time. Musk has claimed SpaceX's AI satellites would require "little" in the way of operating or maintenance costs. That's only true if you accept the narrowest possible interpretation of what maintaining a fleet of AI satellites would entail. "I think that there's no case in which repair makes sense. It's a fly till you die scenario," says McCalip. From an economic perspective, McCalip argues the projected death rate of GPUs in space represents "one of the biggest uncertainties" of the orbital data center model. McCalip's put that number at nine percent on the basis of a study Meta published following the release of its Llama 3 model (which, incidentally, measured hardware failures on Earth.) But the reality is no one knows what the attrition rate of those chips will be until they're in space. Orbital data centers also likely wouldn't be a direct replacement for their terrestrial counterparts. SpaceX's application specifically mentions inference as the primary use case for its new constellation. Inference is the practical side of running an AI system. It sees a model apply its learning to data it hasn't seen before, like a prompt you write in ChatGPT, to make predictions and generate content. In other words, AI models would still need to be trained on Earth, and it's not clear that the process could be offloaded to a constellation of satellites. "My initial thinking is that computations that require a lot of coordination, like AI training, may end up being tricky to get right at scale up there," says Professor Lee. In 1978, a pair of NASA scientists proposed a scenario where low Earth orbit could become so dense with space junk that collisions between those objects would begin to cascade. That scenario is known as Kessler syndrome. One estimate from satellite tracking website Orbiting Now puts the number of objects in orbit around the planet at approximately 15,600. Another estimate from NASA suggests there are 45,000 human-made objects orbiting Earth. No matter the number, what's currently in space represents a fraction of the 1 million additional satellites Musk wants to launch. According to Aaron Boley, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of British Columbia and co-director of the Outer Space Institute, forward-looking modeling of Earth's orbit above 700 kilometers -- where part of SpaceX's proposed cluster would live -- suggests that area of space is already showing signs of Kessler syndrome. While it takes less time for debris to clear in low Earth orbit, Professor Boley says there's already enough material in that region of space where there could be a cascading effect from a major collision. Debris could, in a worst case scenario, take a decade to clear up. In turn, that could lead to disruptions in global communications, climate monitoring missions and more. "You could get to the point where you're just launching material in, and you could ask yourself how many satellites can I afford to lose? Can you reconstitute your constellation faster than you're losing parts of it because of debris?" says Boley. "That's a horrible future in terms of the environmental perspective" In particular, it would limit opportunities for humans to fly into low Earth orbit. "Could you operate in it? Yeah, but it would come with higher and higher costs," adds Boley. "The entire world is struggling with the problem of how we safely fly multiple mega constellations," says Richard DalBello, who previously ran the Traffic Coordination System for Space (TraCSS) at the US Department of Commerce. Right now, there is no common global space situational awareness (SSA) system, and government and satellite operators are using uncoordinated national and commercial systems that are likely producing different results. At the start of the year, SpaceX lowered the orbit of thousands of Starlink satellites after one of them nearly collided with a Chinese satellite. SpaceX has its own in-house SSA system called Stargaze, which it uses to fly its more than 7,000 Starlink satellites. According to DalBello, competing operators can receive SSA data from SpaceX, but to do so they must share their satellite position information. "Assuming data sharing, it is likely Stargaze can make an important contribution to spaceflight safety" says DalBello. "SpaceX is likely to have success with US and other commercial operators, but without the assistance of the federal government, other governments -- particularly China -- will likely be unwilling to share their satellite and SSA data." According to DalBello, the Biden administration was unable to make meaningful progress on the next-generation TraCSS system, in part because Congress was initially reluctant to fund the program. Meanwhile, the current Trump administration hasn't shown interest in advancing the work that began during the president's first term. Even if the regulatory situation suddenly changes and the world's governments agree on an international SSA system, SpaceX launching 1 million satellites along the day-night terminator would see the company effectively monopolize one of the Earth's most valuable and important orbits. Professor Boley argues we should view our planet's orbits as a resource that belongs to everyone. "Every time you put a satellite up, you use part of that resource. Now someone else can't use it." And as Hicks points out, even a single cascade of colliding satellites would prevent that space from being used for scientific endeavors. "You would have to wait years for that debris to slowly come back into the atmosphere and burn up. In the meantime, that debris is taking up space that could be used for climate monitoring missions or any other types of missions that governments want to launch." Separately, the constant churn of Starship launches and re-entry of dead satellites would have a potentially dire impact on our planet's atmosphere. "We're not prepared for it," Boley flatly says of the latter. "We're not prepared for what's happening now, and what's happening now is already potentially bad." According to Musk's "basic math," SpaceX could add 100 gigawatts of AI compute capacity annually by launching a million tons of satellite per year. McCalip estimates a 100-gigawatt buildout alone would necessitate about 25,000 Starship flights. Many of the metals found in satellites, including aluminum, magnesium and lithium, in combination with the exhaust rockets release into the atmosphere, can have complicated effects on the health of the planet. For instance, they can affect polar cloud formations, which in turn can facilitate ozone layer destruction through the chemical reactions that occur on their surfaces. According to Boley, the problem is we just don't know how severe those environmental factors could become at the scale Musk has proposed, and SpaceX has provided us with precious few details on its mitigation plans. All it has said is that its plan would "achieve transformative cost and energy efficiency while significantly reducing the environmental impact associated with terrestrial data centers." Even if SpaceX could and does go out its way to mitigate the atmospheric effects of constant rocket flights, those spacecraft still need to be manufactured here on Earth. At one of his previous roles, Hicks studied rocket emissions and found the supply chains needed to build them produce an "order of magnitude" more carbon emissions than the rockets themselves. SpaceX plans to fly its new satellites in a sun-synchronous orbit, meaning for much of the year, they'll be sunlit. Each new Starlink generation has been larger and heavier than the one before it, with SpaceX stating in a recent filing that its upcoming V3 model could weigh up to 2,000 kilograms, up from the 575 kilograms of the V2 Mini Optimized. While we don't know the exact dimensions of the company's still-hypothetical AI satellites, they will almost certainly be bigger than their Starlink counterparts. SpaceX has done more than most space operators to reduce the brightness of its satellites, but Professor Boley says he expects that this new constellation will be "strikingly bright" when moving through the night sky. In aggregate, he estimates they will almost certainly be harmful to scientific research here on Earth, limiting what terrestrial observatories can see. "You're going to see them with the naked eye. You're going to see them with cameras. It's going to be like living near an airport where you see all these things flying over just after sunset and the next couple of hours after sunset," says Manley. "I don't know if I want to have my entire sunset be just a band of satellites constantly shooting overhead." There are good reasons to make some spacecraft capable of doing AI inference. For instance, Professor Lee suggests it would make orbital imaging satellites more useful, as those spacecraft could do on-site analysis, instead of sending high-resolution files over long distances, saving time in the process. But the dose, as they say, makes the poison. "There's a lot of excitement about the many possibilities that can be brought to society and humanity through continued access to space, but the promise of prosperity is not permission to be reckless," he says. "At this moment, we're allowing that excitement to overtake that more measured progression [...] those impacts don't just impact outer space but Earth as well."

[2]

AI data centers in space are having a moment. Experts say: Not so fast | Fortune

Even as technology companies are projected to spend more than $5 trillion globally on earth-based data centers by the end of the decade, Elon Musk is arguing the future of AI computing power lies in space -- powered by solar energy -- and that the economics and engineering to make it work could align within a few years. Over the past three weeks, SpaceX has filed plans with the Federal Communications Commission for what amounts to a million-satellite data-center network. Musk has also said he plans to merge his AI startup, xAI, with SpaceX to pursue orbital data centers. And at an all-hands meeting last week, he told xAI employees the company would ultimately need a factory on the moon to build AI satellites -- along with a massive catapult to launch them into space. "The lowest-cost place to put AI will be in space, and that will be true within two years, maybe three at the latest," Musk said at the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos this January. Musk is not alone in floating the idea. Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai has said Google is exploring "moonshot" concepts for data centers in space later this decade. Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has warned that the industry is "running out of electricity" and has discussed space-based infrastructure as a potential long-term solution. And Amazon and Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos has said orbital data centers could become the next step in space ventures designed to benefit earth. Still, while Musk and some other bulls argue that space-based AI could become cost-effective within a few years, many experts say anything approaching meaningful scale remains decades away -- especially as the bulk of AI investment continues to flow into terrestrial infrastructure. That includes Musk's own Colossus supercomputer in Memphis, which analysts estimate will cost tens of billions of dollars. They emphasize that while limited orbital computing is feasible, constraints around power generation, heat dissipation, launch logistics, and cost make space a poor substitute for earth-based data centers anytime soon. The renewed interest reflects mounting pressure on the industry to find ways around the physical limits of earth-based infrastructure, including strained power grids, rising electricity costs, and environmental concerns. Talk of orbital data centers has circulated for years, largely as a speculative or long-term concept; but now, experts say, there is additional urgency as the AI boom is increasingly dependent on ever more power to support the training and running of energy-hungry AI models. "A lot of smart people really believe that it won't be too many years before we can't generate enough power to satisfy what we're trying to develop with AI," said Jeff Thornburg, CEO of Portal Space Systems and a SpaceX veteran who led development of SpaceX's Raptor engine. "If that is indeed true, we have to find alternate sources of energy. That's why this has become so attractive to Elon and others." However, while the concept of data centers in space has moved beyond science fiction, it is unlikely to displace the massive AI facilities now being built on earth anytime soon. "This is something people are cynical about because it's just technologically not feasible at the moment," said Kathleen Curlee, a research analyst at Georgetown University's Center for Security and Emerging Technology who studies the U.S. space economy. "We're being told the timeline for this is 2030, 2035 -- and I really don't think that's possible." Thornburg agreed that the hurdles are formidable, even if the underlying physics are sound. "We know how to launch rockets; we know how to put spacecraft into orbit; and we know how to build solar arrays to generate power," he said. "And companies like SpaceX are showing we can mass-produce space vehicles at lower cost. With vehicles like Starship, you can carry a lot of equipment to orbit." As far as it being the right thing to try to move data centers off the ground to take advantage of the solar energy in orbit, he added, "it's a no-brainer." But feasibility, Thornburg cautioned, does not mean being able to build at speed or scale. "I think it's always a question of how long it will take," he said. The first -- and most fundamental -- challenge is power. Running AI data centers in orbit would require "ginormous" solar arrays that do not yet exist, Thornburg said. Today's AI chips, including Nvidia's most powerful GPUs, demand far more electricity than current solar-powered satellites can reliably provide. Boon Ooi, a professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute who studies long-term semiconductor challenges, put the scale into stark perspective: Generating just one gigawatt of power in space would require roughly one square kilometer of solar panels. "That's extremely heavy and very expensive to launch," he said. While the cost of transporting materials to orbit has come down in recent years, it still costs thousands of dollars per kilogram, raising the question of how to lower costs so space-based data centers could compete economically with those on earth. Even in orbit, solar power is not constant. Satellites regularly pass through earth's shadow, and solar panels cannot always remain optimally aligned with the sun. At the same time, AI chips require steady, uninterrupted power, even as their demand spikes during intensive computation. As a result, orbital data centers would also need large onboard batteries to smooth out power fluctuations, said Josep Miquel Jornet, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern University. So far, he noted, only one startup -- Lumen -- has successfully flown even a single Nvidia H100 GPU on a satellite. Cooling presents another unresolved challenge. While space itself is cold, the methods used to cool data centers on earth -- airflow, liquid cooling, and fans -- do not work in a vacuum. "There's nothing that can take heat away," Jornet said. "Researchers are still exploring ways to dissipate that heat." Other obstacles include space traffic jams and communication delays. With growing amounts of space debris in low earth orbit, managing and maneuvering large numbers of satellites would require autonomous collision-avoidance systems, Curlee said. And for many AI workloads, communicating with data centers via satellites would be slower and less energy-efficient than using fiber-connected facilities on the ground. "If you have data centers on earth, fiber connections will always be faster and more efficient than sending every prompt to orbit," Jornet said. The consensus among experts is that small pilot projects may emerge by the end of the decade -- but not anything approaching the scale of today's terrestrial data centers. "What you'll see between now and 2030 is design iteration," Thornburg said, pointing to work on solar arrays, heat rejection systems, and orbital positioning. "Will it be on schedule? No. Will it cost what we think it will? Probably not." Even SpaceX, he added, is still several years away from routinely flying its Starship launch vehicle at the cadence required to support such infrastructure. "They're in the lead, but they still have development to finish," he said. "I think it's a minimum of three to five years before you see something that's actually working properly, and you're beyond 2030 for mass production." Jornet echoed that view. "Two to three years is not realistic at the scale being promised," he said. "You might see three or four or five satellites that together look like a tiny data center. But that would be orders of magnitude smaller than what we build on earth." Still, Thornburg cautioned against dismissing the idea of orbital data centers outright. "You shouldn't bet against Elon," he said, pointing to SpaceX's long history of defying skepticism. In the long run, he added, the energy pressures driving interest in orbital data centers are unlikely to disappear. "Engineers will find ways to make this work," he said. "Long term, it's just a matter of how long is it going to take us."

Share

Share

Copy Link

Elon Musk announced plans to merge SpaceX and xAI to launch a constellation of 1 million satellites operating as orbital data centers. While experts acknowledge the concept isn't fantasy, they warn of devastating environmental effects and technical challenges including heat dissipation, cosmic radiation, and launch logistics that make meaningful scale unlikely before 2030.

SpaceX Files Ambitious Plan for Orbital AI Data Centers

Elon Musk has announced plans to merge two of his companies—SpaceX and xAI—to jointly launch a constellation of 1 million satellites that would function as AI data centers in space

1

. SpaceX filed an eight-page application with the Federal Communications Commission detailing the ambitious AI infrastructure project, proposing to deposit satellites in altitudes ranging between 500km and 2000km1

. The satellites would communicate with one another and SpaceX's Starlink constellation using laser optical links, with Starlink satellites transmitting inference requests to and from Earth1

.

Source: Fortune

Musk isn't alone in exploring orbital computing. Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai has said Google is exploring moonshot concepts for AI data centers in space later this decade, while former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has warned the industry is running out of electricity

2

. Even as technology companies are projected to spend more than $5 trillion globally on earth-based data centers by the end of the decade, these tech leaders argue space-based infrastructure could provide a long-term solution2

.The Case for AI Compute Power in Space

Musk and others argue that putting AI data centers in space makes practical sense given how much more efficient solar panels are away from Earth's atmosphere

1

. In space, there are no clouds or weather events to obscure the sun, and in the correct orbit, solar panels can collect sunlight through much of the day1

. SpaceX has proposed putting the new constellation in sun-synchronous orbit, meaning the spacecraft would fly along the dividing line that separates the day and night sides of the planet1

.

Source: Engadget

Musk has said that within three years space will be the cheapest way to generate AI compute power, combining declining rocket launch costs with the rising price of powering AI data centers on Earth

1

. At the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos this January, he declared: "The lowest-cost place to put AI will be in space, and that will be true within two years, maybe three at the latest"2

.Jeff Thornburg, CEO of Portal Space Systems and a SpaceX veteran who led development of SpaceX's Raptor engine, explained the urgency: "A lot of smart people really believe that it won't be too many years before we can't generate enough power to satisfy what we're trying to develop with AI. If that is indeed true, we have to find alternate sources of energy"

2

.Heat Dissipation Emerges as Critical Challenge

The plan was immediately greeted with skepticism from experts who question how SpaceX would cool millions of GPUs in space

1

. While much of space is around -450 Fahrenheit, the reality is more complicated. In the near vacuum of space, the only way to dissipate heat is to slowly radiate it out, and in direct sunlight, objects can easily overheat1

. As one commenter on Hacker News succinctly put it, "a satellite is, if nothing else, a fantastic thermos"1

.Scott Manley, a former software engineer who studied computational physics and astronomy, argues SpaceX has already solved that problem at a smaller scale with Starlink. He points to the company's latest V3 model, which has about 30 square meters of solar panels and successfully dissipates thermal power generated by electronics

1

. However, Kevin Hicks, a former NASA systems engineer who worked on the Curiosity rover mission, is more skeptical: "Satellites with the primary goal of processing large amounts of compute requests would generate more heat than pretty much any other type of satellite. Cooling them is another aspect of the design which is theoretically possible but would require a ton of extra work and complexity"1

.Related Stories

Cosmic Radiation and Power Generation Concerns

Cosmic radiation poses another significant obstacle for orbital computing. NASA relies on ancient hardware like the PowerPC 750 CPU found inside the Perseverance rover because older chips feature larger transistors, making them more resilient to bit flips—errors in processing caused most often by cosmic radiation

1

. Benjamin Lee, professor of computer and information science at the University of Pennsylvania, explained: "My concern about radiation is that we don't know how many bit flips will occur when you deploy the most advanced chips and hundreds of gigabytes of memory up there"1

.Google's Project Suncatcher explored this issue by bombarding one of its Trillium TPUs with a proton beam, finding the silicon was "surprisingly radiation-hard for space applications"

1

. Yet Professor Lee cautions we simply don't know how resilient GPUs are to radiation at the scale proposed1

.The power generation challenge is equally daunting. Running AI data centers in orbit would require "ginormous" solar arrays that do not yet exist, according to Thornburg

2

. Boon Ooi, a professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, put the scale into stark perspective: generating just one gigawatt of power in space would require roughly one square kilometer of solar panels. "That's extremely heavy and very expensive to launch," he said2

.Timeline Skepticism and Environmental Impacts

Many experts believe anything approaching meaningful scale remains decades away, especially as the bulk of AI investment continues to flow into terrestrial infrastructure, including Musk's own Colossus supercomputer in Memphis, which analysts estimate will cost tens of billions of dollars

2

. Kathleen Curlee, a research analyst at Georgetown University's Center for Security and Emerging Technology, stated bluntly: "We're being told the timeline for this is 2030, 2035—and I really don't think that's possible"2

.Beyond technical feasibility, experts warn that executing this AI infrastructure project at the scale suggested could have devastating effects on the environment and the sustainability of low Earth orbit

1

. The launch logistics alone raise concerns about space debris and the long-term viability of orbital operations. While the AI boom continues to drive demand for more computing power, constraints around heat dissipation, launch logistics, and cost make space a poor substitute for earth-based data centers anytime soon2

.Thornburg acknowledged the hurdles are formidable even if the underlying physics are sound: "We know how to launch rockets; we know how to put spacecraft into orbit; and we know how to build solar arrays to generate power. But feasibility does not mean being able to build at speed or scale. I think it's always a question of how long it will take"

2

. The renewed interest in orbital computing reflects mounting pressure on the industry to find ways around the physical limits of earth-based infrastructure, including strained power grids, rising electricity costs, and environmental concerns—but whether Starship and other advances can overcome these obstacles remains an open question.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

SpaceX pushes AI data centers into orbit as Musk predicts space will beat Earth in 36 months

06 Feb 2026•Technology

AI Trained in Space as Tech Giants Race to Build Orbiting Data Centers Powered by Solar Energy

11 Dec 2025•Technology

SpaceX acquires xAI as Elon Musk bets big on 1 million satellite constellation for orbital AI

29 Jan 2026•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI video generator triggers copyright infringement battle with Hollywood

Policy and Regulation

2

Demis Hassabis predicts AGI in 5-8 years, sees new golden era transforming medicine and science

Technology

3

Nvidia and Meta forge massive chip deal as computing power demands reshape AI infrastructure

Technology