AI Trained in Space as Tech Giants Race to Build Orbiting Data Centers Powered by Solar Energy

6 Sources

6 Sources

[1]

Billionaires want data centers everywhere, including space

Tech billionaires have been obsessed with space for a long time. Now, as the largest AI companies race to build more data centers in a frenzied pursuit of profitability, space is looking less like a pet project and more like a commercial opportunity. In 2025 alone, six proposals for giant AI data centers needing multiple gigawatts of power -- a capacity only rumored of in 2024 -- have been announced. Earthlings are catching on to the fact that power-hungry data centers take up land and water, while providing few jobs, too much pollution, and rising electricity costs. Hence the idea to put the data centers in orbit around the Earth, not on the Earth. Space-based data centers -- in the form of satellites with solar panels -- are Big Tech's latest fad and Silicon Valley's newest investable venture. In space, they theorize, the sun's unlimited rays could provide endless amounts of energy to power your latest AI-generated Sora video. But it's not likely to be that easy. Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Sundar Pichai, and Eric Schmidt (former Google CEO and current CEO of startup Relativity Space), have all recently expanded the focus of their rocket companies to include space data centers. Startups exclusively focused on this idea, like the US-based Aetherflux, have laid out deployment plans. Others have snagged partnerships with big names, like Planet's partnership with Google and Nvidia's backing of Starcloud, which launched a satellite containing H100 GPUs in November as part of the latest SpaceX mission. Earlier this year, China launched a dozen supercomputer satellites that can process data in space. Europe wants in on the action too -- one European think tank called space data centers the next "rapidly emerging opportunity." Yet, scientists who study space remain skeptical of the idea. Astronomer Jonathan McDowell has been tracking every object launched into space since the late 1980s. He told The Verge that, unsurprisingly, it is very expensive to launch something into space. Many business ventures, he said, start from the idea that "'space is cool, let's do something in space,' rather than, 'we really need to be in space to do this.'" The main perk of orbital data centers is access to free, limitless solar power when traveling around the Earth from pole to pole in the sun-synchronous orbit. (Musk's Starlink satellites, in contrast, avoid the poles and stick close to paying customers around the planet's populated middle.) The centers would have to remain in low Earth orbit around 600 to 1,000 miles up from the ground in order to communicate without very large antennas. In November, Google laid out plans for a sun-synchronous low Earth orbital data center called Project Suncatcher, which is slated to kick off in early 2027 with a launch of two prototype satellites. Ultimately, Google says there could be 81 satellites, each carrying TPU chips, traveling together in an arranged cluster one kilometer-square in size. Only 100 to 200 meters would separate each satellite. (For context, typical GPS and Starlink satellites move around individually, not in 81-unit fleets.) Whereas wires connect GPUs together on Earth, Google plans to connect the TPU chips with inter-satellite lasers. Some experts say it would not be smooth sailing, however. The group of satellites would need to travel through millions of pieces of space debris, or "a minefield of random objects, each moving at 17,000 miles an hour," Mojtaba Akhavan-Tafti, associate research scientist of space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan, explained to The Verge. This space debris is especially concentrated in popular orbits like the Sun-synchronous orbit. This is why Google's plan is looking, well, "a little iffy," he said. Dodging each object requires a tiny propulsion to move out of the way. For context, Akhavan-Tafti wrote in a recent Fortune article that the approximately 8,300 Starlink satellites made over 140,000 such maneuvers in just the first half of 2025. Given the close proximity of each satellite in Google's plan, Akhavan-Tafti thinks that the entire constellation, rather than each individual satellite, would need to move out of the way of any incoming debris. "That's really the big challenge," he said. Similarly, McDowell says that a group of 81 satellites traveling together just 100 to 200 meters apart would be "unprecedented" -- typically only two or three, maybe four, spacecraft would travel that close together. The size and closeness present "concerning failure modes." "If a thruster gets stuck, stuck on, or fails, and now you've got a rogue one in among all the others in this cluster of 81," he explains. However, Jessica Bloom, an astrophysicist on Google's Project Suncatcher, told The Verge that the group of 81 satellites is "illustrative," for now, because the final number will depend on money and results from preliminary tests scheduled for 2027. Regardless, satellites can move individually or as a group to avoid debris, Bloom said, and the closeness of the traveling satellites is the most novel part of Google's plan. Bloom explained that the satellites will orbit at the same speed relative to each other, and "relative velocity, rather than proximity, is the key risk factor for damage from impact between objects," she said. "We take our responsibility to the space environment extremely seriously; our approach prioritizes space sustainability and compliance with both current and emerging rules to minimize risk from debris in orbit," Bloom said. In addition to the bones of old satellites, the number of new spacecraft in orbit has dramatically increased over the last few years. There are now more than 14,000 active satellites, roughly two-thirds of which are Starlink, as tracked by McDowell. "As the number of spacecraft increases, you have to dodge more often, so you have to use more fuel," he said. This presents a circular problem: More fuel means a bigger spacecraft, which is a bigger object for other spacecraft to dodge, which means it's more likely to contribute to space debris. Space data centers also have to contend with the uniquely extraterrestrial problem of getting rid of heat in a vacuum. Philip Johnston, CEO of Nvidia-backed startup Starcloud, told The Verge that his company dissipates heat from large infrared panels. In order to keep the electronics safe from radiation, Johnston said they stripped the Nvidia H100 GPU "down to the basics" and shielded the electronics with tungsten, lead, and aluminium, among other materials that are dense and lightweight. But infrared radiation also has the potential to interfere with telescopes, according to John Barentine of the advocacy group the Center for Space Environmentalism. The group has not come out for or against space data centers, Barentine said, but they are concerned about the impact of potential light pollution from reflective surfaces on the spacecraft on astronomy research. Space companies often classify those spacecraft details as "trade secrets," leading to a "chicken-and-egg situation right now," Barentine said. "We can't really say with a lot of certainty what the impacts will be because we don't know the details because the companies haven't or won't disclose them." Starcloud's Johnston said their satellites will never be visible in the night sky, only when the Sun is just about to appear or just after it's set. "You can't really do astronomy at dawn or dusk, anyway," Johnston said. "That is not entirely true," McDowell, who has worked for 37 years as an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told The Verge. "There are things that we do need to observe at dawn and dusk, particularly things near the sun, like asteroids that might be coming close to the Earth -- which we really don't want to miss," he said. Practically, data centers on Earth require regular maintenance to keep the racks of chips humming along, and trained human operators are already in short supply. Repairs of satellites in space, meanwhile, don't happen. Astronauts fix telescopes and equipment attached to the International Space Station or NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. The prospect of robots reorienting or refueling satellites in orbit is theoretically possible but rare. Despite earthly wariness from astronomers outside Big Tech, the popularity of space data centers is likely to continue for years and even decades. Both Google and startup Aetherflux plan to launch satellites in early 2027. Starcloud plans to launch its second satellite in October 2026 and then "ramp up production in 2027, 2028," Johnston said. He views SpaceX as Starcloud's main competitor, despite no official mention from Musk's company on when a space data center might be launched, only a post on X from Musk about SpaceX "simply scaling up Starlink V3 satellites" to achieve this. Blue Origin has reportedly been working on space data centers for over a year but has also not publicly commented on any plans. Constellations close to Earth present good opportunities for "trying to make life better here back on Earth," space scientist Akhavan-Tafti said. But it needs to be done in a sustainable way: "How do we keep low Earth orbit open for business for generations to come?" One option? Avoid launching more stuff into orbit, according to Seth Gladstone of Food & Water Watch, the environmental group leading a petition to halt data center construction. "Why is it that Big Tech always seems to think a solution to its many Earth-bound problems is to blast more stuff into space?"

[2]

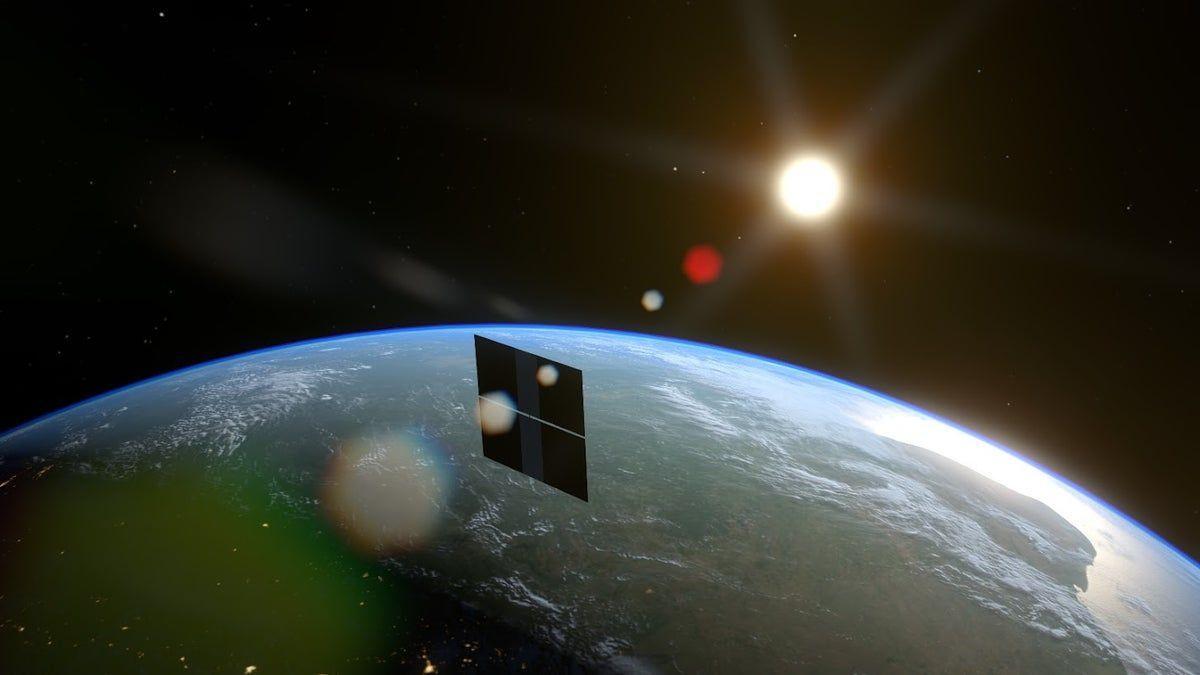

An AI Model Has Been Trained in Space Using an Orbiting Nvidia GPU

A startup says it has successfully trained an AI model in space using an Nvidia GPU that was launched into Earth's orbit last month. Starcloud flew up the Nvidia H100 enterprise GPU on a test satellite on Nov. 2. The company now reports using the Nvidia chip to train a lightweight, open-source AI model called NanoGPT from OpenAI founding member Andrej Karpathy. In addition, Starcloud has been "running inference" on the AI model, meaning it's been used to generate answers or output. The NanoGPT implementation was trained on the complete works of Shakespeare, according to Starcloud Chief Engineer Adi Oltean. The startup has also been running a preloaded open-source AI model from Google called Gemma on the Nvidia GPU, effectively creating a chatbot in space. CNBC reports the test satellite, Starcloud-1, sent back a message reading: "Greetings, Earthlings! Or, as I prefer to think of you -- a fascinating collection of blue and green." The achievement is an early step to place data centers in Earth's orbit, which might kick off a new space race. Major players including SpaceX, Google, and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos have highlighted the potential benefits, such as near‑limitless solar energy. On Earth, AI data centers are sparking concerns about the environmental toll and strain on the electric grid. "This is a significant first step toward moving almost all computing off Earth to reduce the burden on our energy supplies and take advantage of abundant solar energy in space," says Starcloud's Oltean. That said, Starcloud-1 is just one satellite. It's about the size of a small refrigerator and carries a single H100 GPU. In contrast, the AI data centers on Earth are being built to house tens of thousands and even millions of GPUs. The resulting high costs and technical hurdles are why the concept is facing skepticism. One major challenge lies in cooling the GPUs, since the vacuum of space offers no air to dissipate heat. However, Starcloud is eyeing an air-based or liquid-based cooling solution for its satellites. The startup also envisions "the largest radiators deployed in space" to further handle the heat. The company is preparing a second satellite, Starcloud-2, that'll feature even more GPUs. The goal is to launch it sometime next year, and even offer access to customers.

[3]

Data centers in space: Will 2027 really be the year AI goes to orbit?

Google recently unveiled Project Suncatcher, a research "moonshot" aiming to build a data centre in space. The tech giant plans to use a constellation of solar-powered satellites which would run on its own TPU chips and transmit data to one another via lasers. Google's TPU chips (tensor processing units), which are specially designed for machine learning, are already powering Google's latest AI model, Gemini 3. Project Suncatcher will explore whether they can be adapted to survive radiation and temperature extremes and operate reliably in orbit. It aims to deploy two prototype satellites into low Earth orbit, some 400 miles above the Earth, in early 2027. Google's rivals are also exploring space-based computing. Elon Musk has said that SpaceX "will be doing data centers in space", suggesting that the next generation of Starlink satellites could be scaled up to host such processing. Several smaller firms, including a US startup called Starcloud, have also announced plans to launch satellites equipped with the GPU chips (graphics processing units) that are used in most AI systems. The logic of data centers in space is that they avoid many of the issues with their Earth-based equivalents, particularly around power and cooling. Space systems have a much lower environmental footprint and it's potentially easier to make them bigger. As Google CEO Sundar Pichai has said: "We will send tiny, tiny racks of machines and have them in satellites, test them out, and then start scaling from there ... There is no doubt to me that, a decade or so away, we will be viewing it as a more normal way to build data centers." Assuming Google does manage to launch a prototype in 2027, will it simply be a high-stakes technical experiment - or the dawning of a new era? I wrote an article for The Conversation at the start of 2025 laying out the challenges of putting data centers into space, in which I was cautious about them happening soon. Now, of course, Project Suncatcher represents a concrete program rather than just an idea. This clarity, with a defined goal, launch date and hardware, marks a significant shift. The satellites' orbits will be "sun synchronous", meaning they'll always be flying over places at sunset or sunrise so that they can capture sunlight nearly continuously. According to Google, solar arrays in such orbits can generate significantly more energy per panel than typical installations on Earth because they avoid losing sunlight due to clouds and the atmosphere, as well as night times. The TPU tests will be fascinating. Whereas hardware designed for space normally requires to be heavily shielded against radiation and extreme temperatures, Google is using the same chips used in its Earth data centers. The company has already done laboratory tests exposing the chips to radiation from a proton beam that suggest they can tolerate almost three times the dose they'll receive in space. This is very promising, but maintaining a reliable performance for years, amidst solar storms, debris and temperature swings is a far harder test. Another challenge lies in thermal management. On Earth, servers are cooled with air or water. In space, there is no air and no straightforward way to dissipate heat. All heat must be removed through radiators, which often become among the largest and heaviest parts of a spacecraft. Nasa studies show that radiators can account for more than 40% of total power system mass at high power levels. Designing a compact system that can keep dense AI hardware within safe temperatures is one of the most difficult aspects of the Suncatcher concept. A space-based data center must also replicate the high bandwidth, low latency network fabric of terrestrial data centers. If Google's proposed laser communication system (optical networking) is going to work at the multi-terabit capacity required, there are major engineering hurdles involved. These include maintaining the necessary alignment between fast-moving satellites and coping with orbital drift, where satellites move out of their intended orbit. The satellites will also have to sustain reliable ground links back on Earth and overcome weather disruptions. If a space data-center is to be viable for the long term, it will be vital that it avoids early failures. Maintenance is another unresolved issue. Terrestrial data centers rely on continual hardware servicing and upgrades. In orbit, repairs would require robotic servicing or additional missions, both of which are costly and complex. Then there is the uncertainty around economics. Space-based computing becomes viable only at scale, and only if launch costs fall significantly. Google's Project Suncatcher paper suggests that launch costs could drop below US$200 (£151) per kilogram by the mid 2030s, seven or eight times cheaper than today. That would put construction costs on par with some equivalent facilities on Earth. But if satellites require early replacement or if radiation shortens their lifespan, the numbers could look quite different. In short, a two-satellite test mission by 2027 sounds plausible. It could validate whether TPUs survive radiation and thermal stress, whether solar power is stable and whether the laser communication system performs as expected. However, even a successful demonstration would only be the first step. It would not show that large-scale orbital data centers are feasible. Full-scale systems would require solving all the challenges outlined above. If adoption occurs at all, it is likely to unfold over decades. For now, space-based computing remains what Google itself calls it, a moonshot: ambitious and technically demanding, but one that could reshape the future of AI infrastructure, not to mention our relationship with the cosmos around us.

[4]

Nvidia Chip on Satellite in Orbit Trains First AI Model in Space

"Anything you can do in a terrestrial data center, I'm expecting to be able to be done in space." Artificial intelligence companies are planning on investing unbelievable sums -- more than a trillion dollars per year by OpenAI alone -- building out enormous data centers that consume copious amounts of electricity, generate pollution, and take up considerable amounts of room. As critics have pointed out, the logistical obstacles are comically immense, from concerns over economic viability to bandwidth limitations. But, credit where credit is due, there's now a proof of concept. With backing from AI chipmaker Nvidia, a startup called Starcloud launched a high-powered Nvidia GPU into outer space aboard a SpaceX rocket last month. Since then, the company has fired up the chip and is running Google's open-source large language model Gemma, as CNBC reports, marking the first time an AI has been run on a cutting-edge chip in space. The company also says it's managed to train a small-scale LLM on the complete works of Shakespeare, resulting in an AI that can speak in Shakespearean English. "Greetings, Earthlings! Or, as I prefer to think of you -- a fascinating collection of blue and green," the AI wrote in a message. "Let's see what wonders this view of your world holds. I'm Gemma, and I'm here to observe, analyze, and perhaps, occasionally offer a slightly unsettlingly insightful commentary." Starcloud CEO Philip Johnston told CNBC that the concept is sound, and could considerably cut energy costs for AI companies. "Anything you can do in a terrestrial data center, I'm expecting to be able to be done in space," he said. "And the reason we would do it is purely because of the constraints we're facing on energy terrestrially." "Running advanced AI from space solves the critical bottlenecks facing data centers on Earth," he added, while also making strides on "environmental responsibility." As detailed in a white paper, Starcloud has some extremely ambitious plans, especially when it comes to keeping operations in space cool. While data centers on Earth can be cooled using water and air, things get more complicated when it comes to cooling AI chips in outer space. As such, the company wants to build out a five-gigawatt orbital data center that is cooled with enormous cooling panels panels that are more than six square miles in area -- all the while being powered 24/7 by solar power. "Orbital data centers can leverage lower cooling costs using passive radiative cooling in space to directly achieve low coolant temperatures," the white paper reads. "Perhaps most importantly, they can be scaled almost indefinitely without the physical or permitting constraints faced on Earth, using modularity to deploy them rapidly." Thanks to the unconstrained source of solar power, the resulting data center's solar panels would be dramatically smaller than an equivalent solar farm in the US, the company claims. Besides cooling, running orbital data centers have plenty of other challenges to overcome as well, from extreme levels of radiation potentially wreaking havoc on the electronics to maintaining enough fuel to stay in orbit, not to mention avoiding collisions with space junk and questions regarding data regulation in space. Nonetheless, a growing number of firms believe running data centers in orbit is the answer. Starcloud is far from the only entity exploring the idea. Google also recently revealed "Project Suncatcher," an initiative that's aiming to launch the company's in-house tensor processing units into orbit. While Starcloud has partnered with SpaceX to launch its chips, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman is raising funds to either acquire or partner with a competing private space company, as the Wall Street Journal reported earlier this month. "When Starcloud-1 looked down, it saw a world of blue and green," Johnston told CNBC. "Our responsibility is to keep it that way."

[5]

Starcloud Becomes First to Train LLMs in Space Using NVIDIA H100 | AIM

NVIDIA-backed startup Starcloud has successfully trained and run LLMs from space for the first time, a step toward orbital data centres as demand for computing power and energy grows on Earth. The Washington-based company's Starcloud-1 satellite, launched last month with an NVIDIA H100 GPU, has completed training of Andrej Karpathy's nano-GPT on the complete works of Shakespeare and run inference on Google DeepMind's open Gemma model. "We just trained the first LLM in space using an NVIDIA H100 on Starcloud-1! We are also the first to run a version of Google's Gemini in space!" wrote Philip Johnston, founder and CEO of Starcloud, in a post on LinkedIn. "This is a significant step on the road to moving almost all compute to space, to stop draining the energy resources of Earth and to start utilising the near limitless energy of our Sun!" he added. In a post on X, Starcloud CTO Adi Oltean said that getting the H100 operational in space required "a lot of innovation and hard work" from the company's engineering team. He added that the team executed inference on a preloaded Gemma model and aims to test more models in the future. Founded in 2024, Starcloud argues that orbital compute could ease mounting environmental pressures linked to traditional data centres, whose electricity consumption is expected to more than double by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency. Facilities on Earth also face water scarcity and rising emissions, while orbital platforms can harness uninterrupted solar energy and avoid cooling challenges. The startup, part of NVIDIA 's Inception program and an alumnus of Y Combinator and the Google for Startups Cloud AI Accelerator, plans to build a 5-gigawatt space-based data centre powered entirely by solar panels spanning four kilometres in width and height. Such a system would outperform the largest US power plant while being cheaper and more compact than an equivalent terrestrial solar farm, according to the company's white paper. Besides Starcloud, Google, SpaceX and Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin are also pursuing space-based data centres. Google recently announced Project Suncatcher, which explores placing AI data centres in orbit. The initiative involves satellites equipped with custom tensor processing units and linked through high-throughput free-space optical connections to form a distributed compute cluster above Earth. Google CEO Sundar Pichai described space-based data centres as a "moonshot" in a recent interview. He said the company aims to harness uninterrupted solar energy near the sun, with early tests using small machine racks on satellites planned for 2027 and potential mainstream adoption within a decade. Elon Musk, meanwhile, announced in November 2025 that SpaceX would build orbital data centres using next-generation Starlink satellites, calling them the lowest-cost AI compute option within five years. He said Starlink V3 satellites could scale to become the backbone of orbital compute infrastructure. According to a recent report, SpaceX is preparing for an initial public offering in 2026 to raise more than $25 billion at a valuation exceeding $1 trillion. According to Bloomberg News, SpaceX plans to use the IPO proceeds to build space-based data centres and purchase the chips needed to run them. Musk discussed the idea during a recent event with Baron Capital." Starship should be able to deliver around 300 GW per year of solar-powered AI satellites to orbit, maybe 500 GW. The 'per year' part is what makes this such a big deal," he said in a post on X on November 20. "Average US electricity consumption is around 500 GW, so at 300 GW/year, AI in space would exceed the entire US economy just in intelligence processing every 2 years."

[6]

World's 1st LLM trained in space: From earth to orbit on NVIDIA H100 GPUs

Future of compute is moving energy-hungry AI training to space The concept of "cloud computing" has just become literal in the most extreme way possible. In a historic first that signals a new era for artificial intelligence infrastructure, Washington-based startup Starcloud has successfully trained a Large Language Model (LLM) aboard a satellite orbiting 325 kilometers above Earth. This achievement proves that the high-performance computing required for modern AI can survive and function in the vacuum of space. Also read: ChatGPT with Photoshop and Acrobat lowers Adobe's learning curve, here's how The mission began with the launch of the Starcloud-1 satellite aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9. Inside the refrigerator-sized spacecraft sat a piece of hardware never before tested in such an environment: a data center-grade NVIDIA H100 GPU. The Starcloud team used this hardware to train Andrej Karpathy's NanoGPT model on the complete works of Shakespeare. The result was an AI capable of generating text in the Bard's distinct style while traveling at 17,000 miles per hour. Following the training run, the system executed inference on a version of Google's open-source Gemma model. The AI sent a message back to mission control that acknowledged its unique position. It greeted the team with "Hello, Earthlings" and described the planet as a "charming existence composed of blue and green." This successful communication confirmed that delicate tensor operations could be performed accurately despite the harsh conditions of low Earth orbit. Also read: Devstral 2 and Vibe CLI explained: Mistral's bet on open weight coding AI Putting a 700-watt GPU into orbit presented a massive thermal challenge. On Earth, these chips are cooled by complex water and air systems to prevent overheating. In space, there is no air to carry heat away through convection. Starcloud CTO Adi Oltean and his engineering team had to design a system that relies entirely on radiative cooling. This involves using large specialized panels to radiate the intense heat generated by the GPU directly into the freezing void of deep space. Beyond heat, the hardware had to be shielded from cosmic radiation. High-energy particles in space can flip bits in memory and corrupt the training process. The team implemented robust shielding and error-correction protocols to ensure the H100 could operate without the data corruption that typically plagues space-based electronics. This project is more than just a technical stunt. It addresses the growing energy crisis facing the AI industry. Terrestrial data centers currently consume massive amounts of electricity and water. Starcloud CEO Philip Johnston argues that moving compute to orbit allows companies to tap into the sun's limitless energy. In orbit, solar arrays can generate power 24/7 without night cycles or weather interruptions. Furthermore, the natural cold of space eliminates the need for the millions of gallons of water used to cool servers on the ground. The company plans to scale this technology into a 5-gigawatt orbital data center that would rival the largest power plants on Earth. The success of Starcloud-1 has kicked off a race for orbital dominance in the computing sector. Tech giants are already mobilizing. Reports indicate that Google is developing "Project Suncatcher" to deploy similar capabilities using its TPU chips. As AI models grow larger, the sky is no longer the limit for the infrastructure needed to power them. It is simply the next layer of the stack.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Starcloud successfully trained the first AI model in space using an Nvidia H100 GPU aboard its satellite. Google plans to launch Project Suncatcher in 2027, while SpaceX and other tech giants pursue orbital data centers to address the environmental impact of ground-based AI infrastructure and tap into unlimited solar energy.

First AI Model Trained in Space Marks New Era

Startup Starcloud has achieved a milestone by training an AI model in space using an Nvidia H100 GPU launched aboard its Starcloud-1 satellite in November. The company successfully trained NanoGPT, a lightweight open-source model from OpenAI founding member Andrej Karpathy, on the complete works of Shakespeare

2

. The satellite also ran inference on Google's Gemma model, effectively creating a chatbot in orbit that sent back a message reading: "Greetings, Earthlings! Or, as I prefer to think of you -- a fascinating collection of blue and green"4

. This represents the first time an AI has been run on cutting-edge hardware in space, demonstrating that data centers in space could become viable alternatives to their terrestrial counterparts.

Source: Digit

Massive Power Requirements Drive Space Data Center Push

The race toward orbiting data centers stems from mounting concerns about the environmental impact of ground-based AI infrastructure. In 2025 alone, six proposals for giant AI data centers requiring multiple gigawatts of power have been announced

1

. These facilities consume enormous amounts of electricity, take up significant land and water resources, while generating pollution and driving up electricity costs for local communities. According to the International Energy Agency, electricity consumption from traditional data centers is expected to more than double by 20305

. Leveraging solar energy in orbit offers a compelling solution, as space-based systems can capture sunlight continuously without interference from clouds, atmosphere, or nighttime3

.

Source: The Verge

Google Project Suncatcher Targets 2027 Launch

Google recently unveiled Project Suncatcher, an ambitious initiative to deploy AI infrastructure in low Earth orbit approximately 400 miles above Earth. The tech giant plans to launch two prototype satellites in early 2027, with the ultimate goal of operating 81 satellites equipped with TPU chips traveling together in a one-kilometer-square cluster

1

. These satellites would orbit in sun-synchronous paths, ensuring they capture sunlight nearly continuously while transmitting data via inter-satellite lasers. Google CEO Sundar Pichai stated: "We will send tiny, tiny racks of machines and have them in satellites, test them out, and then start scaling from there ... There is no doubt to me that, a decade or so away, we will be viewing it as a more normal way to build data centers"3

. The company's TPU chips, which already power the Gemini 3 AI model, will be tested for their ability to withstand radiation and temperature extremes in orbit.

Source: AIM

Technical Hurdles Challenge Orbital Ambitions

Despite the progress, significant engineering obstacles remain. Thermal management poses one of the most difficult challenges, as the vacuum of space provides no air to dissipate heat. All heat must be removed through radiators, which NASA studies show can account for more than 40% of total power system mass at high power levels

3

. Starcloud proposes building a five-gigawatt orbital data center with massive cooling panels spanning more than six square miles4

. Space debris presents another major concern. The approximately 8,300 Starlink satellites made over 140,000 collision-avoidance maneuvers in just the first half of 20251

. For Google's proposed constellation where satellites would travel just 100 to 200 meters apart, astronomer Jonathan McDowell warns the configuration is "unprecedented" and presents "concerning failure modes" if a thruster malfunctions1

.Related Stories

SpaceX and Tech Giants Join the Race

Elon Musk announced in November 2025 that SpaceX would build data centers in space using next-generation Starlink satellites, claiming they would become the lowest-cost AI compute option within five years

5

. He suggested that Starship could deliver around 300 to 500 gigawatts per year of solar-powered AI satellites to orbit, potentially exceeding the entire US economy's intelligence processing capacity every two years5

. Jeff Bezos and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt have also expanded their rocket companies' focus to include space-based computing. China launched a dozen supercomputer satellites capable of processing data in space earlier this year1

. This growing competition suggests orbital computing could shift from experimental concept to commercial reality within the next decade.Economic Viability Depends on Falling Launch Costs

The financial case for data centers in space hinges on dramatic reductions in launch costs. Google's Project Suncatcher paper suggests launch costs could drop below $200 per kilogram by the mid-2030s, roughly seven or eight times cheaper than current rates

3

. At that price point, construction costs would approach parity with equivalent Earth-based facilities. However, experts remain skeptical. Astronomer Jonathan McDowell, who has tracked every object launched into space since the late 1980s, notes that many ventures start from the premise that "space is cool, let's do something in space" rather than genuine necessity1

. Questions about maintenance, hardware servicing, and early satellite replacement due to radiation damage could significantly impact long-term economics. Starcloud CEO Philip Johnston maintains optimism, telling CNBC that "anything you can do in a terrestrial data center, I'm expecting to be able to be done in space"4

. The company plans to launch Starcloud-2 with additional GPUs next year and eventually offer customer access to orbital computing resources.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

Google Announces Project Suncatcher: Ambitious Plan for AI Data Centers in Space

04 Nov 2025•Technology

Google Plans Space Data Centers to Power AI with Solar Energy, Targets 2027 Launch

02 Dec 2025•Technology

Tech Giants Push Space Data Centers as AI Demands Outpace Earth's Resources

02 Jan 2026•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Nvidia and Meta forge massive chip deal as computing power demands reshape AI infrastructure

Technology

3

ChatGPT cracks decades-old gluon amplitude puzzle, marking AI's first major theoretical physics win

Science and Research