Tech Giants Push Space Data Centers as AI Demands Outpace Earth's Resources

3 Sources

3 Sources

[1]

Even the Sky May Not Be the Limit for A.I. Data Centers

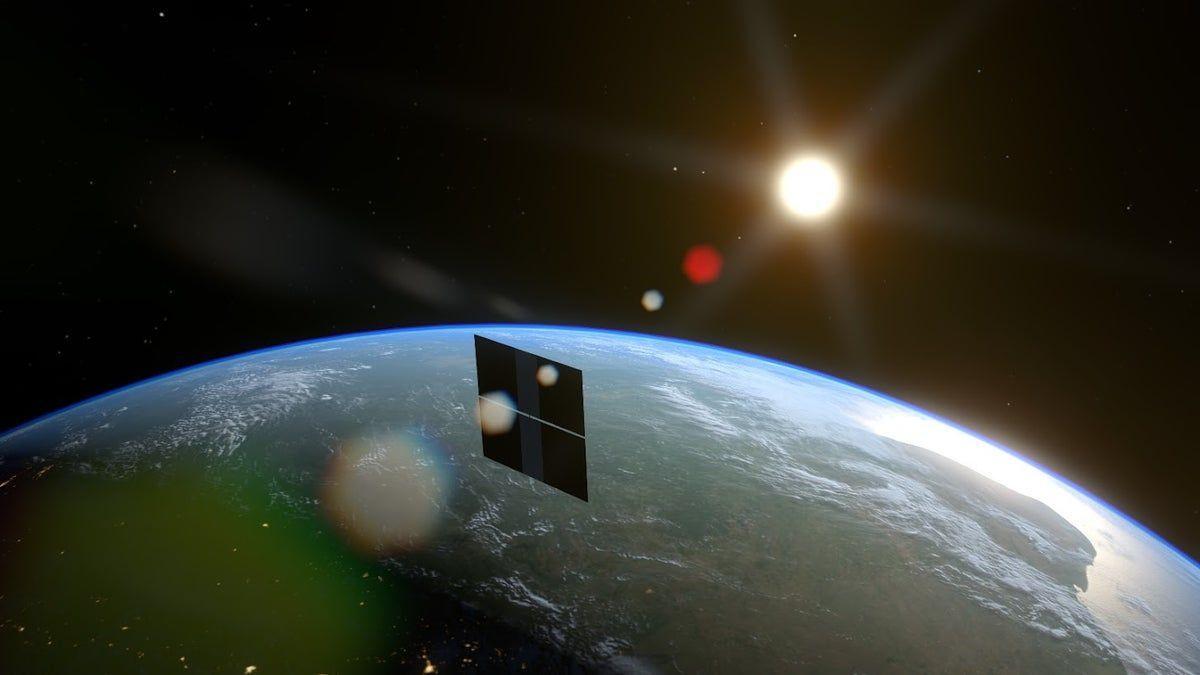

Eli Tan reported from San Francisco and Ryan Mac from Los Angeles. If the architects of the artificial intelligence boom are right, it is only a matter of time before data centers -- the giant computing facilities that power A.I. -- will float in orbit and be visible in the night sky like planets. The science-fiction-like dream is being driven by A.I. and space industry leaders who are growing increasingly worried that data centers will eventually require more energy and land than are available on Earth. So one solution -- perhaps the only solution, they say -- is to start building them in space. Google announced in November that it was working on Project Suncatcher, a space data center project that would begin test launches in 2027. Elon Musk said at a recent conference that space data centers would be the cheapest way to train A.I. "not more than five years from now." Others pledging support for the idea include Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon and Blue Origin; Sam Altman, the chief executive of OpenAI; and Jensen Huang, the chief executive of Nvidia. "It is not a debate -- it is going to happen," said Philip Johnston, the chief executive of Starcloud, a space data center start-up. "The question is when." The notion has gained traction as the A.I. race hits a fever pitch, fueling fears of a potential bubble. Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft, Amazon and other big tech companies are investing hundreds of billions in data centers worldwide, with OpenAI alone committing $1.4 trillion to such projects. Saudi Arabia and other nations are also pouring money into these efforts, while smaller companies pile up debt and take on financial risks to join the frenzy. Yet earthbound data centers are increasingly running into limits. In many places, the projects lack enough available power for the computing needs. Local opposition has also flared over whether data centers are driving up utility bills and exacerbating water shortages. That has led to more creative -- some might say wishful -- thinking with space data centers. Technologists and scientists have researched the idea and concluded that some version of these projects may be possible in the next few decades. But skeptics said the proposals flew in the face of physics and would be astronomically expensive. Tech luminaries like Mr. Musk have also recently made comments about space data centers that are a magnitude larger than what current research suggests is possible, said Pierre Lionnet, a space economist and director at Eurospace, a trade association. "It's completely nonsensical," he said. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration introduced the idea of space data centers in the 1960s. In the 1980s, the concept of "data repositories" in space popped up in science fiction stories. In the last decade, the notion of space data centers that could power modern A.I. also emerged. The main benefit to building a data center in space is abundant energy, with nearly 24/7 access to the sun and no clouds to obstruct the project's solar panels, Mr. Johnston said. There are also fewer environmental regulations than on Earth, not to mention fewer neighbors to oppose the imposition or complain about electric bills. But the feasibility hinges on whether it will become cheaper to launch materials into space and whether technical issues like radiation and cooling can be solved in the meantime. Experts are split on how soon those conditions can be met. "As a business case, it's plausible," said Phil Metzger, a physics professor at the University of Central Florida and a former physicist at NASA. "It's been an evolving discussion." Data centers in space would look different from the football-stadium-size facilities on Earth. Most mock-ups from companies like Starcloud look like large satellites with a cluster of servers housing A.I. chips at the center of miles of solar panels to power them. The data centers would need to be rebuilt every five years, which is when the computer chips are typically replaced, Mr. Johnston of Starcloud said. They would be visible at dawn and dusk from Earth, he said, appearing in the sky as about a quarter the width of the moon. But it is too expensive to create space data centers today. A kilogram of material costs around $8,000 to launch into space, Mr. Lionnet said. The cheapest rate -- around $2,000 per kilogram -- is offered by the rocket maker SpaceX, he added. Individual server racks in a data center can weigh over 1,000 kilograms. If the space-launch costs fall to around $200 per kilogram, the economics will start to make sense, Dr. Metzger said. He predicted that would take around a decade. In a research paper about Suncatcher published in November, Google predicted the costs could decline to that level "in the mid-2030s," comparing the timeline to its driverless robot taxis, which took 15 years to develop. Others said they were not sure the costs would drop in such a short time. "It is like saying if we can get the cost of a McDonald's cheeseburger down to 10 cents, we will buy so many of them," Mr. Lionnet said. Modern computer chips and semiconductors are also not built to withstand the radiation in space, which would hurt their ability to compute reliably, said Benjamin Lee, an electrical and systems engineering professor at the University of Pennsylvania. And while space is a frigid minus 455 degrees Fahrenheit, it is also a vacuum. That means there is no air to transfer the heat from the A.I. chips. To cool the chips, the data centers would instead require large radiator panels to disperse the heat. Such hurdles have not stopped people like Mr. Musk, who leads SpaceX and the artificial intelligence start-up xAI. Mr. Musk started engaging with others about space data centers in November on X, the social media platform he owns, saying that "serious AI scaling" had to "be done in space." In another post, he mused about building 300 gigawatts of space data centers, which would require more than half of the power that the United States uses in a year. Bret Johnsen, SpaceX's chief financial officer, said in a letter to shareholders last month that the company would explore an initial public offering next year partly to raise money for projects including "A.I. data centers in space." SpaceX and Mr. Musk did not respond to requests for comment. Tom Mueller, a former SpaceX executive who believes humans will hit the limits of terrestrial energy sources by 2040, said part of the reason Mr. Musk and other A.I. leaders were talking about space data centers was the financial opportunity. "The hottest thing to invest in right now is A.I., and the second-hottest thing is space," Mr. Mueller said. "Now they're converging."

[2]

As AI Grows, Should We Move Data Centers to Space?

Before entering the data center game, Bhatt was working on the technology of space-based power generation -- using satellites to collect and store the power of the sun and transmitting it back down to Earth. In many cases, that power would be used to operate terrestrial data centers, and that whole multi-step process felt wasteful to Bhatt. "Rather than beaming the power down to the ground and then converting it back to electricity to run a data center, the more efficient sort of first principles approach would be to put the data center on the satellite," he says. "You put the chips right next to the power generation." Google is taking a similar approach. The planners behind the company's Project Suncatcher envision clusters of satellites flying in close formation just hundreds of meters to a kilometer (.62 mi.) apart. "That close formation facilitates really high bandwidth, low latency communication between all of the satellites," says Google's Travis Beals, whose business card marvelously reads "senior director, paradigms of intelligence." Each cluster would be part of a larger cluster of clusters, exponentially increasing the collective processing power. "Imagine a string of pearls in Earth orbit," Beals says. Not all AI infrastructure in space would involve processing data; some would simply be about storing it. Imagine a catastrophic government-wide or industry-wide data crash -- due either to cyber collapse or cyber attack. Somehow, Washington or the commercial sector would have to reboot, restoring data on payroll, salaries, taxation, human resources, intelligence, law enforcement, military deployment, and more. Best to keep backups of all of that data stashed, cached, and out of harm's way -- and space makes an ideal safe deposit box.

[3]

Even the sky may not be the limit for AI data centres

AI leaders believe Earth may soon lack the power and space for data centres, pushing them to look skyward. Big tech figures are backing the idea of building computing hubs in orbit, despite huge costs and doubts. Supporters say it is inevitable, while critics call it unrealistic. If the architects of the artificial intelligence boom are right, it is only a matter of time before data centres -- the giant computing facilities that power AI -- will float in orbit and be visible in the night sky like planets. The science-fiction-like dream is being driven by AI and space industry leaders who are growing increasingly worried that data centres will eventually require more energy and land than are available on Earth. So one solution -- perhaps the only solution, they say -- is to start building them in space. Google announced in November that it was working on Project Suncatcher, a space data centre project that would begin test launches in 2027. Elon Musk said at a recent conference that space data centres would be the cheapest way to train AI "not more than five years from now." Others pledging support for the idea include Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon and Blue Origin; Sam Altman, the chief executive of OpenAI; and Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia. "It is not a debate -- it is going to happen," said Philip Johnston, the CEO of Starcloud, a space data centre startup. "The question is when." The notion has gained traction as the AI race hits a fever pitch, fuelling fears of a potential bubble. Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft, Amazon and other big tech companies are investing hundreds of billions in data centres worldwide, with OpenAI alone committing $1.4 trillion to such projects. Saudi Arabia and other nations are also pouring money into these efforts, while smaller companies pile up debt and take on financial risks to join the frenzy. Yet earthbound data centres are increasingly running into limits. In many places, the projects lack enough available power for the computing needs. Local opposition has also flared over whether data centres are driving up utility bills and exacerbating water shortages. That has led to more creative -- some might say wishful -- thinking with space data centres. Technologists and scientists have researched the idea and concluded that some version of these projects may be possible in the next few decades. But sceptics said the proposals flew in the face of physics and would be astronomically expensive.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Google announced Project Suncatcher for 2027 test launches while Elon Musk predicts space data centers will become the most cost-effective AI training solution within five years. Industry leaders including Jeff Bezos, Sam Altman, and Jensen Huang back the orbital computing vision as terrestrial facilities face power shortages and local opposition.

Tech Leaders Bet on Building Data Centers in Orbit

The escalating demands of AI are pushing industry leaders to consider a radical solution: space data centers that would orbit Earth like visible planets in the night sky. Google revealed in November that it's developing Project Suncatcher, targeting test launches in 2027

1

. Elon Musk declared at a recent conference that space data centers would become "the cheapest way to train A.I. not more than five years from now"1

. Other prominent supporters include Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon and Blue Origin, Sam Altman of OpenAI, and Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang3

. Philip Johnston, CEO of space data center startup Starcloud, stated emphatically: "It is not a debate -- it is going to happen. The question is when"1

.

Source: ET

Why Artificial Intelligence Infrastructure Needs to Leave Earth

The push for computing hubs in orbit stems from mounting constraints facing terrestrial data centers. Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft, Amazon and other tech giants are investing hundreds of billions in AI data centers worldwide, with OpenAI alone committing $1.4 trillion to such projects

1

. Saudi Arabia and other nations are pouring money into these efforts as the AI race intensifies. Yet earthbound facilities increasingly lack sufficient power for their computing needs. Local opposition has flared over concerns that AI data centers drive up utility bills and worsen water shortages1

. These limitations are forcing the space industry and AI sector to explore alternatives for powering the artificial intelligence sector.

Source: TIME

How Space Data Centers Would Actually Work

Space data centers would look dramatically different from football-stadium-size facilities on Earth. Most designs from companies like Starcloud resemble large satellites with server clusters housing AI chips at the center, surrounded by miles of solar panels

1

. The primary advantage is abundant solar energy, with nearly 24/7 access to the sun and no clouds obstructing panels, Johnston explained1

. Google's Project Suncatcher envisions satellites flying in close formation just hundreds of meters to a kilometer apart. "That close formation facilitates really high bandwidth, low latency communication between all of the satellites," says Google's Travis Beals, whose title is senior director of paradigms of intelligence. "Imagine a string of pearls in Earth orbit"2

. These orbital facilities would need rebuilding every five years when computer chips require replacement and would appear in the sky at dawn and dusk as about a quarter the width of the moon1

.

Source: NYT

Related Stories

The Economics and Technical Hurdles of AI Scaling in Space

Current launch costs make space data centers prohibitively expensive. A kilogram of material costs around $8,000 to launch into space, with SpaceX offering the cheapest rate at approximately $2,000 per kilogram

1

. Individual server racks can weigh over 1,000 kilograms. Phil Metzger, a physics professor at the University of Central Florida and former NASA physicist, predicts the economics will make sense when launch costs drop to around $200 per kilogram, which he estimates will take about a decade1

. Google's November research paper on Project Suncatcher predicted costs could decline to that level "in the mid-2030s," comparing the timeline to its driverless robot taxis, which required 15 years to develop1

. Technical challenges including radiation and cooling must also be resolved. Space economist Pierre Lionnet, director at Eurospace trade association, calls recent claims by tech luminaries about the magnitude of space data centers "completely nonsensical," saying proposals fly in the face of physics1

.Secure Data Storage and Protection from Cyber Threats

Not all AI infrastructure in orbit would process data—some would focus on secure data storage. In the event of a catastrophic government-wide or industry-wide data crash due to cyber collapse or cyber threats, organizations would need to reboot and restore critical data on payroll, taxation, intelligence, law enforcement, and military deployment

2

. Space offers an ideal safe deposit box, keeping backups cached and out of harm's way. The concept dates back to NASA's introduction of space data centers in the 1960s, with "data repositories" in orbit appearing in 1980s science fiction1

. Metzger acknowledges the business case as plausible, noting "it's been an evolving discussion"1

. The notion has gained traction as concerns about an AI bubble grow, with energy consumption and environmental regulations on Earth becoming increasingly restrictive. Whether this vision materializes in five years or several decades, the conversation reflects how AI scaling challenges are reshaping both the space industry and artificial intelligence development.References

Summarized by

Navi

Related Stories

AI Trained in Space as Tech Giants Race to Build Orbiting Data Centers Powered by Solar Energy

11 Dec 2025•Technology

Google Announces Project Suncatcher: Ambitious Plan for AI Data Centers in Space

04 Nov 2025•Technology

Google Plans Space Data Centers to Power AI with Solar Energy, Targets 2027 Launch

02 Dec 2025•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI Releases GPT-5.4, New AI Model Built for Agents and Professional Work

Technology

2

Anthropic sues Pentagon over supply chain risk label after refusing autonomous weapons use

Policy and Regulation

3

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round as questions swirl around AI bubble and profitability

Business and Economy