AI Decodes Rules of Mysterious Roman Board Game After 1,700 Years of Silence

7 Sources

7 Sources

[1]

An ancient Roman game board's secrets are revealed -- with AI's help

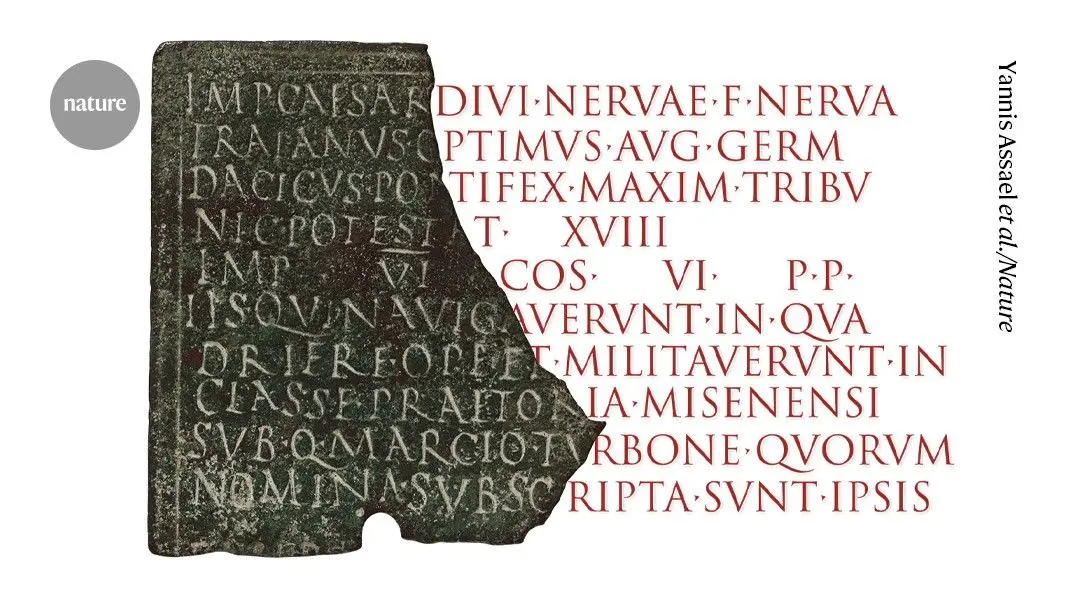

You have full access to this article via Jozef Stefan Institute. A mysterious ancient Roman object found in what is now the southern tip of the Netherlands has long been thought to be some sort of board game. With the help of artificial-intelligence simulations, Walter Crist at Leiden University in the Netherlands and his collaborators have now found that it was most likely a 'blocking game', a type of board game that was not known to exist in Europe before the Middl e Ages. The oval-shaped board has a pattern of carved lines that do not resemble those of any of known game, modern or ancient. Microscopic analysis revealed wear patterns consistent with game pieces, such as glass pebbles, being repeatedly dragged along the surface, particularly along one of the carved lines. The authors created a digital model of the pattern and made two AI opponents play against each other, following a range of rules based on a database of rules of traditional board games. The simulations showed that the wear patterns were most consistent with a blocking game -- one in which the goal is to prevent the opponent from moving their pieces.

[2]

Rules of mysterious ancient Roman board game decoded by AI

It was the summer of 2020, and researcher Walter Crist was wandering around the exhibits inside a Dutch museum dedicated to the presence of the ancient Roman empire in the Netherlands. As a scientist who studies ancient board games, one exhibit stuck out to Crist: a stone game board dating to the late Roman Empire. It was about eight inches across and etched with angular lines that roughly formed the shape of an oblong octagon inside a rectangle. "I thought to myself, 'Well, that's very interesting,' because the pattern on it -- it's not something I had ever seen in the literature before," Crist says. What the game was called and how it was played were a mystery, too. If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today. Crist contacted the museum curators to get a closer look. And now he and his colleagues believe they've decoded the game in a first-of-its-kind study using a combination of more traditional archaeological methods and artificial intelligence. According to the analysis, the object appears to be a sort of "blocking game." In these types of games, one player tries to block another from moving; one example is tic-tac-toe. The research was published on Monday in the journal Antiquity. Crist, now a guest lecturer at Leiden University in the Netherlands, recalls that when he and his team started investigating the board game, they didn't have a ton of details to work with. They knew that the game board had been found around the late 1800s or early 1900s in the southeastern Netherlands' city of Heerlen -- which would have been the city of Coriovallum in Roman times. The board was made out limestone that was imported from France. And the game was likely played casually and may not have been particularly notable, in part because there is no known documentation of it in written texts from the time. To decipher the rules, Crist's team programmed two AI agents to play the game over and over again using more than 100 different sets of rules taken from other known European games, both ancient and modern. As the AI agents played -- 1,000 games per set of rules -- the researchers tracked how the pieces moved. Then they compared the moves with the levels of wear on areas of the board, tracing which gameplay seemed to replicate grooves on the stone. The team found nine rule sets that appeared "consistent" with the wear on the board. "And they were all variations of this same kind of blocking game," Crist says. This type of game was played in the 19th and 20th centuries in Scandinavia, and researchers thought it dated to early medieval times. But the Roman game is the earliest example of such a game in Europe, Crist says. He and his team called the game Ludus Coriovalli, Latin for "the game from Coriovallum." (You can play it online here.) Crist hopes the study will help researchers solve other ancient board games. Such games offer a way to connect the ancient past to our own lives, he says. Indeed, they haven't changed much over the centuries. The ancient Egyptian board game Senet, for example, might not have been all that different from Sorry! Chess, meanwhile, is thought to have originated in ancient India, and nobody really knows when or where backgammon originated. Understanding how ancient games might've been played, Crist says, "can lead us to new insights on how people in the past enjoyed their lives."

[3]

AI helps archaeologists solve a Roman gaming mystery

The researchers used virtual players to test possible combinations of pieces and moves An old, flattened piece of limestone inscribed with a crisscross of grooves looks like the board for a game, but for nearly a century, no one knew how the game was played. Now, researchers have used artificial intelligence to reverse-engineer the rules, revealing the board was probably part of a "blocking" game played by the Romans. The innovative approach to solving how the game was played had virtual game players run through more than 100 sets of possible rules. The researchers' goal was to determine which set of rules best created the wear patterns on the limestone, Leiden University archaeologist Walter Crist and his colleagues report in the February Antiquity. Archaeologist Véronique Dasen of Switzerland's University of Fribourg called the study "groundbreaking" and added that the technique could be used to investigate other "lost" games. "The research results invite [archaeologists] to reconsider the identification of Roman period graffiti that could be actual boards for a similar game not present in texts," she says. The board, just 20 centimeters across, was found in the Dutch city of Heerlen and put on display in a local museum. Heerlen sits atop the ruins of the Roman town of Coriovallum. The board's archaeological context is unknown, and there are no records of such a game from Roman times, which lasted until the fifth century in this region. Given the board's size, the game probably had only two players. The researchers used the AI-driven Ludii game system to pit the two virtual players against each other in thousands of possible games, derived in part from the known rules of later games. Ludii uses a specialized "game description language" to drive its virtual players; in this case, the games were designed to test different configurations of pieces and moves so that the researchers could determine which rules might have produced the wear patterns. "We tried many different kinds of combinations: three versus two pieces, or four versus two, or two against two ... we wanted to test out which ones replicated the wear on the board," Crist says. The game, called Ludus Coriovalli, or the "Coriovallum Game," can now be played online against a computer. The result suggests that, on limestone at least, one player took turns placing four pieces in the grooves against an opponent's two. The winner was the player who avoided being blocked the longest. Blocking games like this weren't thought to have been played in Europe until the Middle Ages, Crist says. Go and Dominoes are modern blocking games, but Ludus Coriovalli doesn't resemble either of those. Some archaeologists of games say the study is the beginning of a breakthrough. "If more were known about the board's context and potential game pieces, more interpretations could be made of how it functioned in past social life," says University of North Florida anthropologist Jacqueline Meier, who was not involved in the research. Dasen also wasn't involved but led the Locus Ludi project to study ancient Roman and Greek board games and other forms of play. She says blocking games were once popular in Europe and that their names in several languages indicate they were often likened to hunting. But there had been no evidence until now that the Romans knew of this type of game, she says. "Games can go on for centuries, and sometimes they appear and then disappear."

[4]

Scientists solve ancient Roman board game mystery using AI

The limestone rock measures 21 by 14.5 centimetres and was found in the ground in the Dutch city of Heerlen in the late 19th or early 20th century. In Roman times, Heerlen was an important settlement called Coriovallum. The rock has a rectangle carved into it, containing four diagonal lines and one straight line. In 2020, archaeologist Walter Crist came across the stone in a local museum and was immediately fascinated by the mysterious slab. "The stone's appearance, together with the wear, strongly suggested a game, but I didn't recognise the pattern from other ancient games I know," he explained. Mr Crist decided to take a closer look at the stone under a microscope, and then started working together with a team of specialists, who were able to produce highly detailed 3D scans of the rock. "The scans make the traces on the stone much clearer," he explained. "Some of those traces are a fraction of a millimetre deeper than others, meaning they were used more intensively. "We also see that the edges of the stone are neatly finished, which indicates that this is a finished product and not a stone that still needs further working." The team then used artificial intelligence to try and identify the board game based on the lines, and the rules of other known board games from that time. They discovered that the wear on the stone was most likely linked to the playing of so-called blocking games - board games in which the goal is to prevent the opponent from moving. Previously it was thought that this type of board game was first played in the Middle Ages. However, with the stone estimated to be between 1,500 to 1,700 years old, researchers now believe that this type of game was played several centuries earlier than previously thought. The team hopes that the new AI approach may help scientists make more old gaming discoveries in the future. Mr Crist explained: "This research provides archaeologists with additional tools to identify games from ancient cultures."

[5]

Dueling AIs Reconstruct Rules of Mysterious Roman-Era Board Game

In the hands of a non-expert, the oval artifact doesn’t look like much of anything. However, geometric patterns on one of its two broad sides, along with other clues, suggest it to be a stone board game. In a study published today in the journal Antiquity, researchers used artificial intelligence to test this theory, as well as identify what the game rules may have been. Those who came before us enjoyed board games, just like we do; the pastime dates back to the Bronze Age, at least. The problem, however, is that the components of many of these games were not nearly as enduring as Monopoly’s houses and hotels will surely prove to be. As such, the stone object that came to light in Coriovallumâ€"a Roman town in modern-day Netherlandsâ€"could be a rare opportunity to investigate ancient nerds. “We identified the object as a game because of the geometric pattern on its upper face and because of evidence that it was deliberately shaped,†Walter Crist, lead author of the study and an archaeologist at Leiden University specializing in ancient board games, explained in an Antiquity statement. “Further evidence that it was a game was presented by visible damage on the surface that would be consistent with abrasion caused by sliding Roman-era game pieces on the surface.†There’s only one problem. The aforementioned geometric pattern doesn’t align with any game known to researchers. To investigate the matter, Crist and his colleagues did what many people faced with a question tend to do these daysâ€"they asked AI to give it a go. Given the artifact’s human-caused abrasions, the team used AI to model potential game rules. “The damage was unevenly distributed along the lines of the board,†Crist said. “We sought to answer the question of whether we could use AI-driven simulated play as a tool to discover playing rules that would replicate this disproportionate pattern of use wear on the surface of this board with rules similar to those documented for other small games in Europe, thus confirming that the object was likely to have been a game board.†The researchers had two AIs play a large number of ancient European board games, including Scandinavia’s Haretavl and Italy’s Gioco dell’orso, until they landed on one that could have caused the stone board’s wear-and-tear. This approach ultimately revealed a match with blocking games, a kind of board game whose objective consists of blocking the other player’s movement (just like Ticket to Ride, if you play like my fiendish partner). It also bolsters the preexisting theory that the artifact was a board game after all. “This is the first time that AI-driven simulated play has been used in concert with archaeological methods to identify a board game,†Crist concludes. “This research provides archaeologists with the tools to be able to identify games from ancient cultures that are unusual or uncommonly played, since current methods for identification rely on connecting the geometric patterns that make up the playing surface to games that are known today from references in text, or from artistic representations of them.†Interestingly, previously known traces of blocking games only appeared in Europe starting in the Middle Ages and are overall very rare in the region. In other words, the study suggests that people may have played these types of games centuries earlier than researchers thought. All that’s left to discover is how many tears were shed and friendships broken over the movementâ€"or notâ€"of pieces on this board.

[6]

Rules of mysterious ancient board game decoded by AI, scientists say

A smooth, white stone dating from the Roman era and unearthed in the Netherlands has long baffled researchers. Now, with the help of artificial intelligence, scientists believe they have cracked the mystery: the stone is an ancient board game and they have even guessed the rules. The circular piece of limestone has diagonal and straight lines cut into it. Using 3D imaging created by the restoration studio Restaura, scientists discovered some lines were deeper than others, suggesting pieces were moved along them, some more than others. "We can see wear along the lines on the stone, exactly where you would slide a piece," said Walter Crist, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands who specializes in ancient games, in a statement. "The appearance of the stone combined with this wear strongly suggests it's a game." Other researchers at Maastricht University then used an artificial intelligence program that can deduce the rules of ancient games. They trained this AI, baptized Ludii, with the rules of about 100 ancient games from the same area as the Roman stone. The computer "produced dozens of possible rule sets. It then played the game against itself and identified a few variants that are enjoyable for humans to play," Dennis Soemers, from Maastricht University, said in a statement. They then cross-checked the possible rules with the wear on the stone to uncover the most likely set of movements in the game. However, Soemers also sounded a note of caution. "If you present Ludii with a line pattern like the one on the stone, it will always find game rules. Therefore, we cannot be sure that the Romans played it in precisely that way," he said. The aim of the "deceptively simple but thrilling strategy game" was to hunt and trap the opponent's pieces in as few moves as possible, scientists said. Researchers said they believe glass, bone or earthenware were used as game pieces. The research and the possible rules were published in the journal Antiquity, which posted a video on social media explaining the game. "We know the rules we found explain the wear marks on the stone and that they are consistent with games from comparable cultural periods," Karen Jeneson, curator of The Roman Museum in Heerlen, said in a statement. "Of course we considered other possible uses for the stone, such as an architectural decorative feature, but we found no alternative explanation. So, the stone really is a board game." In 2015, scientists said they uncovered board game pieces, including dice, in an ancient Roman settlement in a German town located on the Rhine River.

[7]

AI cracks Roman-era board game

The Hague (AFP) - A smooth, white stone dating from the Roman era and unearthed in the Netherlands has long baffled researchers. Now with the help of artificial intelligence, scientists believe they have cracked the mystery: the stone is an ancient board game and they have even guessed the rules. The circular piece of limestone has diagonal and straight lines cut into it. Using 3D imaging, scientists discovered some lines were deeper than others, suggesting pieces were moved along them, some more than others. "We can see wear along the lines on the stone, exactly where you would slide a piece," said Walter Crist, an archaeologist at Leiden University who specialises in ancient games. Other researchers at Maastricht University then used an artificial intelligence programme that can deduce the rules to ancient games. They trained this AI, baptised Ludii, with the rules of about 100 ancient games from the same area as the Roman stone. The computer "produced dozens of possible rule sets. It then played the game against itself and identified a few variants that are enjoyable for humans to play," said Dennis Soemers, from Maastricht University. They then cross-checked the possible rules with the wear on the stone to uncover the most likely set of movements in the game. However, Soemers also sounded a note of caution. "If you present Ludii with a line pattern like the one on the stone, it will always find game rules. Therefore, we cannot be sure that the Romans played it in precisely that way," he said. The aim of the "deceptively simple but thrilling strategy game" was to hunt and trap the opponent's pieces in as few moves as possible. The research and the possible rules were published in the journal Antiquity.

Share

Share

Copy Link

A mysterious limestone tablet discovered in the Netherlands has puzzled researchers for over a century. Now, artificial intelligence has cracked the code, revealing it as a blocking game played by Romans—centuries earlier than such games were thought to exist in Europe. The breakthrough demonstrates how AI simulations can unlock secrets of ancient cultures.

AI Helps Archaeologists Unlock Ancient Gaming Secrets

When Walter Crist walked through a Dutch museum in the summer of 2020, he encountered something that stopped him in his tracks. An oval-shaped limestone tablet, measuring about eight inches across, sat in an exhibit dedicated to the Roman Empire in the Netherlands

2

. The ancient Roman game board featured angular lines etched into its surface, forming a pattern that the Leiden University researcher had never seen in archaeological research1

. Dating back 1,500 to 1,700 years to the late Roman Empire, the artifact had been discovered in Heerlen—once the Roman settlement of Coriovallum—sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s4

. But what game it represented and how people played it remained a complete mystery.

Source: Nature

Microscopic Analysis Reveals Critical Clues

Crist, now a guest lecturer at Leiden University, contacted museum curators for closer examination of the stone

2

. Working with specialists, his team produced highly detailed 3D scans and conducted microscopic analysis of the 21-by-14.5-centimeter limestone tablet4

. The investigation revealed wear patterns consistent with game pieces—such as glass pebbles—being repeatedly dragged along the surface, particularly along one of the carved lines1

. "Some of those traces are a fraction of a millimetre deeper than others, meaning they were used more intensively," Crist explained4

. The neatly finished edges indicated this was a completed product, not an unfinished stone, strengthening the case that it functioned as an actual game board.

Source: Science News

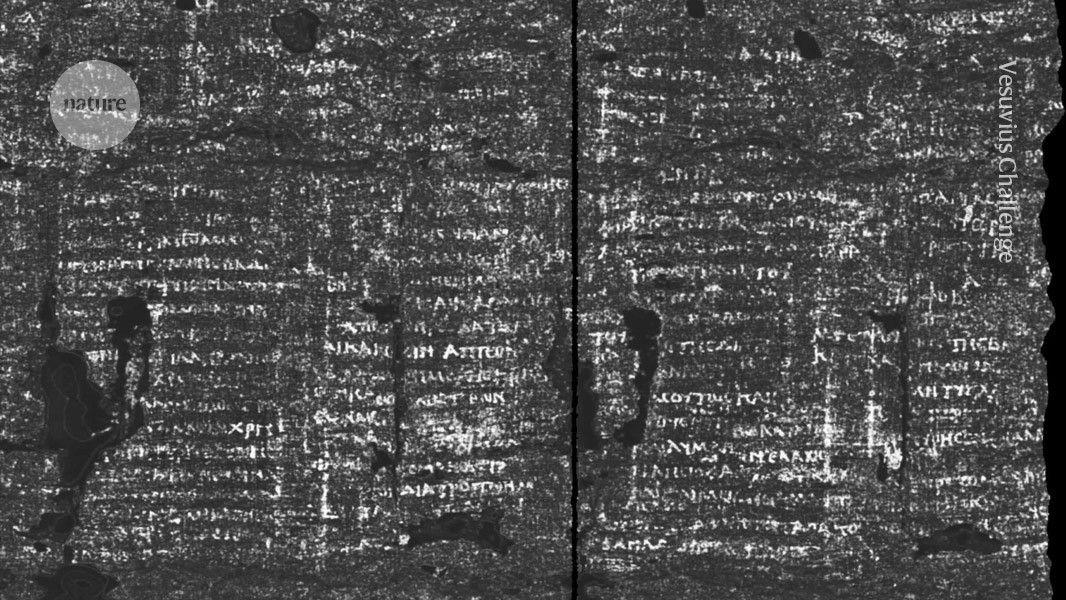

Digital Modeling and AI Simulations Reconstruct Rules of Board Game

Faced with limited historical documentation—the game appeared in no written texts from Roman times—Crist's team turned to artificial intelligence

2

. They created a digital model of the pattern and programmed two AI opponents to play against each other using the Ludii game system3

. The researchers tested more than 100 different sets of rules taken from other known European games, both ancient and modern, including Scandinavia's Haretavl and Italy's Gioco dell'orso5

. As the AI agents played 1,000 games per rule set, the team tracked how pieces moved and compared the gameplay patterns with the levels of wear on areas of the board2

.

Source: Gizmodo

Related Stories

Blocking Game Discovery Rewrites European Gaming History

The AI simulations showed that wear patterns were most consistent with a blocking game—one in which the goal is to prevent the opponent from moving their pieces

1

. The team identified nine rule sets that appeared consistent with the board's wear, and "they were all variations of this same kind of blocking game," Crist noted2

. The results suggest one player took turns placing four pieces in the grooves against an opponent's two, with victory going to whoever avoided being blocked the longest3

. The researchers named it Ludus Coriovalli, Latin for "the game from Coriovallum," and the game can now be played online2

.Groundbreaking Method Opens New Research Possibilities

This Roman board game represents the earliest example of such a blocking game in Europe—a type previously thought to have emerged only during the Middle Ages

1

. "This is the first time that AI-driven simulated play has been used in concert with archaeological methods to identify a board game," Crist stated5

. Véronique Dasen of Switzerland's University of Fribourg called the study "groundbreaking" and noted the technique could investigate other lost games3

. The research results invite archaeologists to reconsider Roman period graffiti that could represent actual boards for similar games not present in texts. Published in the journal Antiquity, this approach provides archaeologists with tools to identify games from ancient cultures that are unusual or uncommonly played, since current identification methods rely on connecting geometric patterns to games known from historical references or artistic representations5

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

[3]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

OpenAI secures $110 billion funding round from Amazon, Nvidia, and SoftBank at $730B valuation

Business and Economy

2

Trump orders federal agencies to ban Anthropic after Pentagon dispute over AI surveillance

Policy and Regulation

3

Google releases Nano Banana 2 AI image model with Pro quality at Flash speed

Technology