Fed Chair Powell Distinguishes AI Boom from Dot-Com Bubble as Tech Giants Pour Trillions into Infrastructure

10 Sources

10 Sources

[1]

The Fed Chair Is Not Worried About an AI Bubble. Here's Why It Differs From the 90s

US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell (Credit: JIM WATSON / Contributor / AFP via Getty Images) Are we in an AI bubble? Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell is not convinced. "This is different," Powell told reporters on Wednesday when asked about applying any lessons from the 1990s dot-com crash to today's AI boom. "If you go back to the '90s and the dot-com [era], these were ideas rather than companies," he added. "So, there's a clear bubble there. Whereas -- I won't go into particular [tech company] names -- but [today's top performers] actually have earnings, and it looks like they have business models and profits. So it's really a different thing." In other words, Powell believes businesses like Amazon, which reported $18 billion in profit last quarter, have ongoing revenue streams to keep the companies afloat, even if their AI ambitions don't pan out. An economic bubble is the "rapid escalation in asset prices, often due to speculative behavior, followed by a sharp contraction," according to Investopedia. They're hard to identify in real-time, but lead to "significant economic consequences" once they burst. The dot-com bubble of the late 1990s is one of the most notable examples, along with the Japanese economic contraction in the 1980s, and the Dutch "Tulip Mania" of the 1630s. Today, it's not speculative tulip investments that would bring down the economy, but data centers. The sums of money tech companies are pouring into them are astronomical, suggesting a high level of confidence that has sent stocks soaring. Nvidia just hit the $5 trillion valuation mark. Earlier this year, OpenAI, Oracle, and Softbank pledged to invest $500 billion in AI data centers over the next four years via their Stargate project. Yesterday, Amazon opened an $11 billion data center in Indiana, while Google, Microsoft, Meta, and others have similar plans. Data centers require a small number of employees, but building them generates temporary business for suppliers and construction companies. "The investment we're getting into equipment and all the things that go into creating data centers and feeding AI, it's clearly one of the big sources of growth in the economy," Powell said this week. He admitted he couldn't say if the data center investments "will work out," but does not think they will affect interest rates either way, which is his primary concern. (On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates by a quarter point.) Still, the AI hype is not translating into a hiring boom. Amazon just laid off 14,000 corporate employees, citing the need to move fast in AI (and pay for the GPUs needed to power it), which might climb to 30,000 in 2026. In June, Meta invested $14.3 billion in ScaleAI and poached its founder to lead AI at Meta, but recently laid off 600 employees as part of a team restructuring. When asked about whether AI is contributing to layoffs, Powell said it's too soon to tell, but it's an area the Federal Reserve is concerned about and watching closely. "You see a significant amount of companies announcing that they are not going to be doing much hiring or are actually doing layoffs, and much of the time they are talking about AI and what it can do," he said. "It could absolutely have implications for job creation. We don't see it in the initial [jobless] claims data yet, but it takes some time to get in there. We are watching that very carefully, but don't see it yet." The government shutdown is further hampering efforts to secure the federal employment data report for September. In its absence, Powell referenced "anecdotal data" from earnings reports, where companies are discussing a "bifurcated economy," meaning very different activity among high-income consumers who are still spending a lot, and lower-income consumers who are tightening their belts. "We think there's something there," Powell said. Other data points the Fed is using as a proxy for the official, federal report -- such as unemployment insurance claims and job listings on Indeed -- show that the situation has been "stable" over the last few weeks, Powell said. Regarding tariffs, which have hit tech companies like Apple, Powell seemed cautiously optimistic. "Higher tariffs are pushing up prices in some categories of goods, resulting in higher overall inflation," he said. "A reasonable base case is that the effects on inflation will be relatively short-lived, a one-time shift in the price level. "But it is also possible that the inflationary effects could instead be more persistent," he cautioned. "And that is a risk to be assessed and managed. Our obligation is to ensure that a one-time increase in the price level does not become an ongoing inflation problem."

[2]

The Fed's Wait-and-See Approach to AI Can't Last

Financial markets are obsessed with AI, and the broader public is aware of its looming impact on jobs and wages. Yet for the Federal Reserve, the concern has barely registered. This isn't because its policymakers think AI doesn't matter. It's because they have no idea how its potentially vast repercussions will play out -- and no good tools for shaping the outcome. Last week, as Amazon cut thousands of corporate positions and Nvidia's market capitalization climbed to $5 trillion, Chair Jerome Powell was asked about the subject during the press conference that followed the Fed's latest policy announcement. A significant number of companies, he said, "are either announcing that they are not going to be doing much hiring, or actually doing layoffs, and much of the time they're talking about AI and what it can do. So, we're watching that very carefully."

[3]

Powell says AI is different from dotcom bubble and is major source of economic growth

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell speaks during a news conference following a meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee at the Federal Reserve on Oct. 29, 2025 in Washington, DC. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said on Wednesday that the artificial intelligence boom is different from the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s. "This is different in the sense that these companies, the companies that are so highly valued, actually have earnings and stuff like that," Powell said, during a news conference following the Fed's two-day policy meeting. AI investments in data centers and chips are also a major source of economic growth, he said. In the dotcom era, numerous companies raced to big valuations before going bankrupt due to hefty losses. Powell didn't name specific vendors, but chipmaker Nvidia has emerged as the world's most valuable company, surpassing $5 trillion in market cap. The rally has been driven by the company's graphics processing units, which are at the heart of AI models and workloads. However, while Nvidia is generating big profits, high-valued startups OpenAI and Anthropic have been burning cash as they develop and expand their services. OpenAI has racked up $1 trillion in AI deals of late, despite being set to generate only $13 billion in annual revenue. Anthropic, which is at a $7 billion revenue run rate, last week announced an estimated $50 billion cloud partnership with Google.

[4]

Jerome Powell Deeply Concerned About AI's Effects on Job Market

If you had a hunch that the economy is in the tubes lately, you're not alone: Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell agrees with you. After his long-anticipated Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting on Wednesday, Powell told reporters that "job creation is very low, and the job-finding rate for people who are unemployed is very low." Per Fortune magazine, Powell added that a "significant number of companies" have been contributing to the malaise by laying off workers or pausing hiring. Their reason? None other than artificial intelligence. "Much of the time they're talking about AI and what it can do," the Fed chair said about executives of large corporations. "We're watching that very carefully." Powell's cynical comments come after the Fed announced that it'd cut interest down to around 3.75-4.0 percent, the lowest level in three years, CNN reported. The Fed board has been facing something of an impossible situation over the past few months, juggling both rising unemployment and severe inflation. In a healthy market economy it's typically understood that employment and inflation have an inverse relationship -- when one goes up, the other goes down. In 2025, however, both are rising at the same time, placing an increased burden on working-class households, and putting the Fed in an impossible situation. As the number of people out of work goes up, corporations are able to use the pressure of hungry hands to keep wages for actual workers low. The effect of this horrible job growth -- fueled by the hype of the AI narrative -- is an economy where the rich spend like sailors, while the poor get much poorer. As Powell put it: "consumers at the lower end are struggling and buying less and shifting to lower-cost products," while high income households and corporations enjoy the strongest stock market in history.

[5]

Powell suggested tech giants fueling the AI boom and GDP hardly care about Fed rate tweaks. They just proved him right | Fortune

While Wall Street seems to live and die on the slightest hints about the Federal Reserve's rate stance, Chairman Jerome Powell doesn't think the tech giants behind the AI boom will be swayed by incremental moves in monetary policy. After the Fed cut rates by another 25 basis points on Wednesday, Powell noted the AI spending explosion is supported by actual earnings, unlike the dot-com bubble. As a result, borrowing costs are less of an issue. "I don't think the spending that happens to build data centers all over the country is especially interest-sensitive," he said. "It's based on longer-run assessments that this is an area where there's going to be a lot of investment that's going to drive higher productivity and that sort of thing." Powell added companies are "making money in building them -- it's not about 25 basis points here or there." In fact, Morgan Stanley has estimated the so-called AI hyperscalers plan to spend about $3 trillion on data centers and other infrastructure through 2028, with about half that amount likely coming from cash flows. Right on cue, earnings reports late Wednesday from Alphabet, [hotlink]Meta Platforms,[/hotlink] and Microsoft showed they made a combined $78 billion in capital expenditures in the third quarter alone, up 89% from a year earlier. And the spending will speed up. Google said its capital expenditures for this year would be $91 billion-$93 billion, up from a prior view of $75 billion-$85 billion and the $52.5 billion spent in 2024. Meta said investment will grow "notably larger" in 2026 after nearly doubling this year to $72 billion. The social-media giant also sold $30 billion in corporate bonds this week to help feed the spending spree, despite spooking investors about the additional debt it's taking on. And on Thursday, Amazon CEO Andy Jassy said the company will "continue to be very aggressive in investing capacity" because demand is strong enough to support it. "As fast as we're adding capacity right now, we're monetizing it." Similarly, Microsoft said the tens of billions of dollars in recent spending are still not enough to satisfy the enormous demand for AI and related services. "I thought we were going to catch up," CFO Amy Hood said. "We are not. Demand is increasing. It is not increasing in just one place. It is increasing across many places." The tech giants are also borrowing from private credit. UBS recently estimated at least $50 billion in private credit has been flowing to AI each quarter for the past three quarters. That's about two to three times what public credit markets are providing. All that investment is moving the needle on the U.S. economy. Powell acknowledged as much on Wednesday, and JPMorgan recently estimated AI-related capex contributed 1.1 percentage points to GDP growth in the first half of this year, outpacing consumer spending as a growth driver. The nature of AI spending is also evolving and will continue to felt across the economy, according to JPMorgan global market strategist Stephanie Aliaga. "Official data primarily reflect the first phase of AI investment, emphasizing chips, servers, and networking equipment," she said in a note last month. "This next phase is targeting supporting infrastructure such as power plants and grid upgrades, which can take years to plan, permit, and build. Early signs of this phase are emerging, but the full impact is likely ahead."

[6]

Jerome Powell says the AI hiring apocalypse is real: 'Job creation is pretty close to zero.' | Fortune

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell drew a stark picture of a labor market that looks fine on the surface -- 4.3% unemployment, solid consumer spending -- but is quietly losing momentum underneath. Once you adjust for statistical overcounting in the payroll data, he said during a press conference Wednesday following the FOMC meeting, "job creation is pretty close to zero." He connected that slowdown, at least in part, to what CEOs are now openly telling investors: AI allows them to do more with fewer people. He noted "a significant number of companies" have recently announced layoffs or hiring pauses, with many of them explicitly citing AI as the reason. "Much of the time they're talking about AI and what it can do," Powell told reporters after the Fed's rate-cut decision, warning large employers are signaling they won't need to add headcount for years. "We're watching that very carefully," he added. The comments come as the Fed cut interest rates by a quarter point to a range of 3.75%-4%, citing "downside risks to employment" even as inflation remains elevated. Powell said the U.S. economy is still expanding at a "moderate pace," even as hiring slows. He described that spending as one of the "big sources of growth in the economy," driven by companies building data centers and other equipment tied to artificial intelligence. Powell also pushed back on the idea that all that spending is amounting to another speculative bubble. He drew a clear line between today's surge in capital expenditure and the dot-com era, noting "these companies actually have earnings." Those projects, he said, aren't especially sensitive to interest rates, though, since they reflect long-term bets on higher productivity. At the same time, Powell emphasized the boom creates a policy dilemma for the Fed. AI and automation are boosting output, but they're also allowing companies to do more with fewer workers, leaving the labor market softer, even while GDP stays positive. "We have upside risks to inflation, downside risks to employment," he said. "This is a very difficult thing for a central bank, because one of those calls for rates to be lower, one calls for rates to be higher." Recent corporate announcements illustrate Powell's warning. Amazon announced this week it laid off 14,000 middle managers -- about 4% of its white-collar workforcein an effort to "remove organizational layers." The layoffs come amid their rampant investments into AI. Target, Paramount, and other large firms followed with their own cuts. According to a Challenger, Gray & Christmas report, U.S. employers have announced nearly 946,000 layoffs so far this year -- the highest total since 2020 -- with more than 17,000 explicitly tied to AI and another 20,000 to automation. "Job creation is very low, and the job-finding rate for people who are unemployed is very low," Powell said. The phenomenon is so widespread some economists have coined a new term -- the "Great Freeze" -- to describe the dismal labor market conditions. With unemployment among recent college grads topping 5% -- and AI threatening to automate entry-level office jobs -- many Gen Z workers are turning to graduate school as a strategic timeout. That awkward balance -- strong investment but weak hiring -- is now at the center of the Fed's decision-making. Powell said the economy increasingly resembles a K-shape, with higher-income households and large corporations benefiting from strong stock markets and AI-fueled productivity gains, while lower-income consumers pull back under the weight of rising costs. He pointed to anecdotal reports from major retailers and consumer companies describing a "bifurcated economy," in which wealthier Americans continue to spend freely but those at the bottom are trading down to cheaper goods. " "Consumers at the lower end are struggling and buying less and shifting to lower-cost products," Powell said, noting the uneven effects of growth make the Fed's balancing act even more complicated. "There is no risk-free path for policy," Powell said. "We're navigating the tension between our employment and inflation goals as carefully as we can."

[7]

Jerome Powell: AI boom is not a bubble, could 'absolutely' affect job market

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said Wednesday he did not believe the massive growth in artificial intelligence (AI) investment and spending was a bubble. At a press conference following the Fed's latest rate cut, Powell contrasted the explosive growth of AI companies with the dot-com bubble of the 2000s. "This is different," Powell said, explaining that leading AI companies actually have a track record to show for their sky-high valuations, unlike the scores of firms that went bust during the start of the century. "These [AI] companies, the companies that are so highly valued, actually have earnings and stuff like that," Powell said. While the defunct giants of the dot-com bubble were "ideas rather than companies," Powell said, the leading companies in AI are building out actual infrastructure through data centers and tech development. "The investment we're getting in equipment and all those things go into creating data centers and feeding the AI, it's clearly one of the big sources of growth in the economy," Powell said. A growing number of influential tech and financial figures, including leading AI executives, have warned of a potential bubble within the AI industry after years of exponential growth. Investment in AI has been one of the few bright spots in the U.S. economy, particularly as President Trump's tariffs stifle growth in other areas of the economy. Policymakers have also become increasingly concerned with the potential impact AI could have on the job market, particularly after a string of major companies announced plans to cut staff, driven partly by developments in the technology. "You see a significant number of companies either announcing that they are not going to be doing much hiring or actually doing layoffs," Powell said. "And much of the time they're talking about AI and what it can do. So we're watching that very carefully." "It could absolutely have implications for job creation," he added.

[8]

Powell gave traders a green light to double down on AI -- but the markets punished Meta and Microsoft anyway | Fortune

U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell bifurcated the stock market yesterday when he delivered a 0.25% rate cut that the market was expecting and then, unexpectedly, said he did not believe that the AI sector was in a bubble akin to the dotcom boom of 2000. The broad index of large-cap companies in the S&P 500 closed flat, but the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 rose 0.55%. Tech stocks were led by Nvidia, which was up 3%, and now has a market cap of more than $5 trillion. (Its stock is down 0.7% premarket this morning, suggesting that some traders are taking their overnight gains.) To put that in perspective, Nvidia's market cap is bigger than the GDP of every G7 country except the U.S. and Japan. Powell's remarks about AI were extensive -- he was asked about it repeatedly in a Q&A session with reporters. At every turn, he insisted that the Fed was unbothered by the run-up in valuations of AI companies and the massive amount of capex spending they have triggered. "I don't think that the spending that happens to build data centers all over the country is especially interest-sensitive. It's based on longer run -- it's, you know, longer-run assessments that this is an area where there's going to be a lot of investment and that it's going to drive higher productivity and that sorts of things," he said. "These companies -- the companies that are so highly valued actually have earnings and stuff like that. So if you go back to the '90s and the dotcom, they were -- these were ideas rather than companies, and you know, were -- so there's a clear bubble there. Whereas the -- you know, I won't go into particular names, but they actually have earnings and, you know, it looks like they have business models and profits and that kind of thing. So it's really a different thing," he added. Powell all-but gave the tech sector the green light to keep investing in AI, in other words, because he said he doesn't need to raise interest rates to choke off any irrational exuberance. Investors -- after digesting earnings reports from Meta, Microsoft, and Alphabet -- reacted soberly. Meta shares are down 8.6% premarket after closing flat yesterday, in part because investors were unimpressed with the company's spending on AI. It was a similar story at Microsoft, which is down 2.64% premarket after closing flat yesterday. But Alphabet (Google) shares are up 7% premarket, even though that company is also continuing to spend big on AI. "Microsoft, Meta and Alphabet send contrasting signals on the payoffs from the AI investment boom. The three tech giants saw their joint capex bill rise +89% y/y to $78bn in the latest quarter. But with Meta delivering in line revenue guidance for the current quarter ($56-59bn vs $57.4bn est.) and Microsoft saying that capacity was still constraining growth in its cloud unit (+39% y/y vs +37% est.), this left questions hanging over increasingly lofty expectations," Jim Reid et al at Deutsche Bank told clients this morning. "There has simply never been a company like it in the history of financial markets. With Microsoft (-0.10%) also surpassing $4tn earlier this week, and Apple (+0.26%) doing so yesterday, these companies are now more akin to countries than corporations," Reid said.

[9]

Why the Fed's wait-and-see approach to AI can't last

The Federal Reserve faces a significant challenge with AI's unpredictable economic impacts, as it struggles to develop tools to manage its potential job displacement and inflation effects. While AI fuels market exuberance and demand, it also causes layoffs and hiring reluctance, creating conflicting signals for monetary policy. Financial markets are obsessed with AI, and the broader public is aware of its looming impact on jobs and wages. Yet for the Federal Reserve, the concern has barely registered. This isn't because its policymakers think AI doesn't matter. It's because they have no idea how its potentially vast repercussions will play out -- and no good tools for shaping the outcome. Last week, as Amazon cut thousands of corporate positions and Nvidia's market capitalization climbed to $5 trillion, Chair Jerome Powell was asked about the subject during the press conference that followed the Fed's latest policy announcement. A significant number of companies, he said, "are either announcing that they are not going to be doing much hiring, or actually doing layoffs, and much of the time they're talking about AI and what it can do. So, we're watching that very carefully." That was about it. AI is already having conflicting macroeconomic effects. The stock market's unshakable exuberance, which relaxes the "financial conditions" the Fed has to weigh when it sets its policy rate, rests on optimism about the big AI innovators. Massive outlays on AI software and equipment are powering overall demand. At the same time, the job market is limping thanks to layoffs and a marked reluctance to hire -- most likely caused, in part, by companies waiting to see how AI will change their businesses and their need for workers. As yet, these disturbances have no clear implication for monetary policy. On the face of it, a bubbly stock market and elevated spending on AI raise demand and call for higher interest rates. A sluggish labor market suggests the opposite. For now, doing nothing except "watching that very carefully" looks reasonable. Before long, this stance will be hard to sustain. The likely effects of AI have what you might call quantitative and qualitative dimensions. AI could be a big deal or not such a big deal. And it could be a good thing or a bad thing. Small effects, good or bad, would complicate the Fed's job by muddying the signals it uses to guide policy, but needn't keep its policymakers up at night. Big effects, good or bad, could make their job -- combining "maximum employment" with 2% inflation -- much harder, and perhaps impossible. Unsurprisingly, expert opinion is divided on where things will go, but suppose for the sake of argument that AI proves to be a truly transformative technology -- on a par with the adoption of electric power. That would suggest a boost to productivity growth of maybe one percentage point a year for the next several decades. This supply-side push in turn implies a higher long-term neutral real interest rate (known as r-star), combined with lower inflation because of falling costs of production. The Fed's appropriate response, given its inflation target of 2%, would be to cut the policy rate, but by less than the fall in inflation. Getting that right is already tricky, but that's just the start. So far, this scenario is one of good big effects: It assumes higher productivity plus the implicitly smooth adoption of displaced workers into different jobs, with little else changing. But big effects could easily turn bad. The AI revolution could replace certain kinds of workers abruptly and en masse, as opposed to gradually making workers in general more productive. True, similarly dire predictions have been made about every wave of innovation, only to be proven wrong (eventually). Still, AI seems more directly aimed at saving labor through automation than many of its predecessors, and might arrive much faster and more forcefully. Lower wages, higher unemployment and rising inequality as the labor force divides between workers empowered and disempowered by AI would pressure the Fed to do something -- but what, exactly? Its only policy tool, the short-term interest rate, is beside the point in confronting a structural shift of this kind. The Fed can always engineer higher inflation; it can't always raise real wages or find jobs for the unemployable. Another plausible bad effect is greater price-raising power for the technology's leaders and earliest adopters. As with collapsing demand for labor, this isn't to be taken for granted: In the end, an open-source AI ecosystem might emerge to keep would-be AI monopolists in check and promote competition more broadly. At the moment, though, network effects and economies of scale appear to have the upper hand. Economic prospects hinge on how this turns out. The Fed can only stand and watch. Short-term macro management is squarely in its wheelhouse, but the difficulties aren't confined to ambiguous economic signals and a fluctuating neutral rate. AI could also amplify the short-term business cycle by making it easier for employers to cut jobs in a downturn. If supply chains are designed and managed by AI, and fail because of shocks not previously encountered, the technology might make things worse -- and there'll be fewer humans to put things right. The same goes for financial markets. Once they're guided by models trained on history and opaque to human judgement, radical novelties (such as AI) could throw them for a loop, causing bigger, faster, self-reinforcing errors. The next crash could break records. Call me an alarmist, but tweaking the federal funds rate will not suffice. Handling these possibilities demands smarter policy across an unnervingly wide front: a stronger safety net to cushion the blow for displaced workers; judicious regulation to temper the threat to competition; tax reform to guard against surging inequality; labor-market reform to improve occupational mobility; and, above all, schools and colleges capable of training students before their careers begin and throughout their working lives. If things go badly, the Fed will doubtless get more than its fair share of the blame. But the truth is, AI is too big for any central bank to cope with on its own. The technology calls for politicians willing to think hard about these challenges and face them. Let me know if you see one.

[10]

Powell says that, unlike the dot-com boom, AI spending isn't a bubble: 'I won't go into particular names, but they actually have earnings' | Fortune

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell doesn't think the AI boom is another dot-com bubble. In fact, he made that distinction explicit on Wednesday, arguing that the current wave of artificial-intelligence investment is grounded in profit-making firms and real economic activity rather than speculative exuberance. "I won't go into particular names," Powell told reporters after the Fed's policy meeting, "but they actually have earnings." "These companies... actually have business models and profits and that kind of thing. So it's really a different thing" than the dot-com bubble, he added. The comments mark what seems like Powell's most direct acknowledgment yet that AI's corporate build-out -- spanning hundreds of billions of dollars in data-center and semiconductor investments -- has become a genuine engine of U.S. growth. Powell emphasized that the explosion of AI spending isn't being driven by monetary policy -- or by cheap money. "I don't think interest rates are an important part of the AI or data-center story," he said. "It's based on longer-run assessments that this is an area where there's going to be a lot of investment, and that's going to drive higher productivity." That remark cuts against one market narrative that loosening financial conditions might be fueling an asset bubble in tech. Instead, Powell suggested that the AI build-out is more structural: a bet on the long-term transformation of work. From Nvidia's on track to have half a trillion dollars in revenue to Microsoft and Alphabet's multi-hundred-billion-dollar capital-expenditure plans, the scale is unprecedented. But, in Powell's telling, it's also grounded. Goldman Sachs agrees. In a research note titled "The AI Spending Boom Is Not Too Big," chief U.S. economist Joseph Briggs argued that "anticipated investment levels are sustainable, although the ultimate AI winners remain less clear." Briggs and his team estimated that the productivity unlocked by AI could be worth $8 trillion in present value to the U.S. economy, and potentially as much as $19 trillion in high-end scenarios. "We are not concerned about the total amount of AI investment," the Goldman team wrote. "AI investment as a share of U.S. GDP is smaller today (<1%) than in prior large technology cycles (2%-5%)." In other words, there's still plenty of room to run. Powell's framing echoes that view: the AI race, while frothy at times, is being financed mainly through corporate cash flow rather than speculative debt. Powell noted that the investment wave is showing up in the real economy. "It's the investment we're getting in equipment and all those things that go into creating data centers and feeding the AI," he said. "It's clearly one of the big sources of growth in the economy." Those remarks align with private-sector estimates. JPMorgan economists have projected that AI-related infrastructure spending could add up to 0.2 percentage points to U.S. GDP growth over the next year, roughly the same annual boost that shale drilling delivered at its peak. The boom has already pushed industrial power demand to record levels and forced utilities to fast-track grid expansion, confronting with the realities of a too-slim grid. The AI boom isn't just reflected on paper, in other words: Powell is talking about cranes, concrete, capital goods. Still, Powell didn't give AI a free pass. He stressed that while the current investment surge looks healthy, it's too early to call it a permanent productivity revolution. "I don't know how those investments will work out," he said. For all its promise, the AI economy is unevenly distributed: capital-intensive and concentrated among a handful of firms. Economists warn that productivity gains from AI will take years to filter through the broader workforce, and that automation could suppress hiring in sectors now driving demand. Powell acknowledged as much when he noted that many recent layoff announcements from major corporations "are talking about AI and what it can do."There's an irony, there: the same technology boosting output may also slow job creation -- one of the central bank's two mandates. Powell said job growth, adjusted for statistical over-counting, is now "pretty close to zero."Powell says that, unlike the dot-com boom, AI spending isn't a bubble: "I won't go into particular names, but they actually have earnings"

Share

Share

Copy Link

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell argues the current AI investment surge differs fundamentally from the 1990s dot-com bubble, citing actual earnings and business models. However, he expresses concern about AI's impact on employment as companies announce layoffs while investing heavily in data centers.

Fed Chair Distinguishes AI Investment from Historical Bubbles

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell drew a sharp distinction between today's artificial intelligence investment surge and the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s during a press conference following the Fed's latest policy meeting. When asked about potential parallels to the speculative frenzy that preceded the dot-com crash, Powell was emphatic: "This is different"

1

.

Source: PC Magazine

Powell's reasoning centers on fundamental business metrics that were absent during the dot-com era. "If you go back to the '90s and the dot-com [era], these were ideas rather than companies," he explained. "So, there's a clear bubble there. Whereas [today's top performers] actually have earnings, and it looks like they have business models and profits"

1

. Companies like Amazon, which reported $18 billion in profit last quarter, demonstrate the revenue streams that distinguish current AI leaders from their dot-com predecessors1

.Massive Infrastructure Investments Drive Economic Growth

The scale of AI-related capital expenditures has reached unprecedented levels, with tech giants demonstrating their commitment through concrete financial commitments. Recent earnings reports revealed that Alphabet, Meta, and Microsoft combined spent $78 billion on capital expenditures in the third quarter alone, representing an 89% increase from the previous year

5

. Google raised its 2025 capital expenditure guidance to $91-93 billion, up from a prior range of $75-85 billion5

.

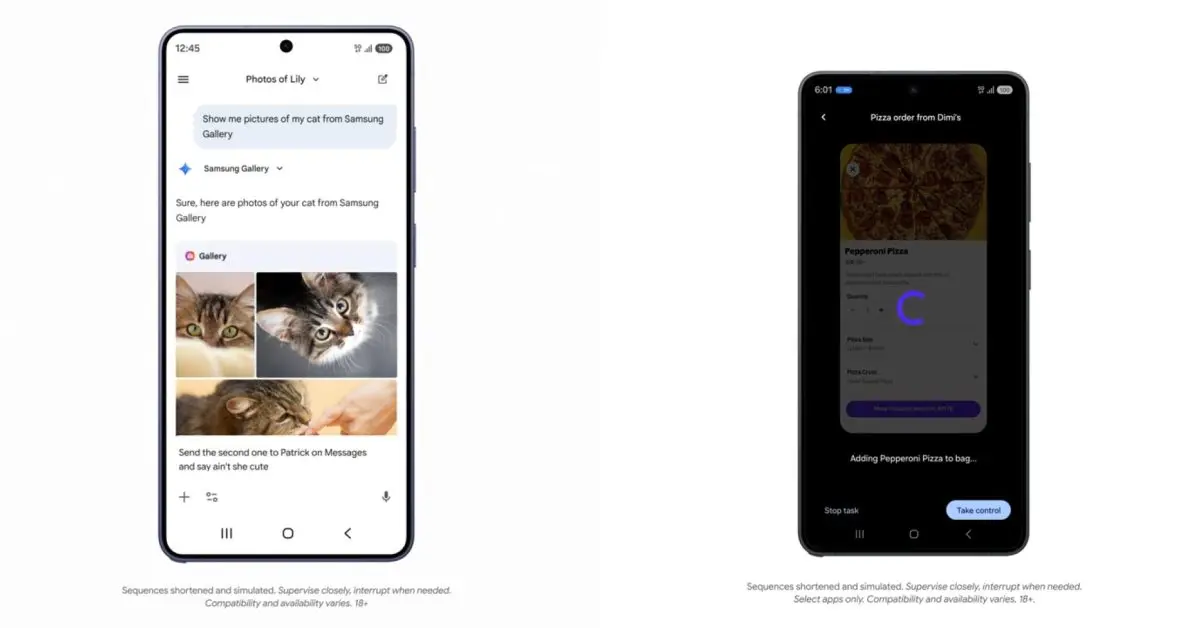

Source: Fortune

Morgan Stanley estimates that AI hyperscalers plan to invest approximately $3 trillion in data centers and infrastructure through 2028, with roughly half funded through cash flows

5

. This investment wave includes major projects like OpenAI, Oracle, and Softbank's $500 billion Stargate initiative and Amazon's recent $11 billion data center opening in Indiana1

.Powell acknowledged this spending as "clearly one of the big sources of growth in the economy," noting that data center construction generates temporary business for suppliers and construction companies

1

. JPMorgan estimates that AI-related capital expenditures contributed 1.1 percentage points to GDP growth in the first half of this year, outpacing consumer spending as a growth driver5

.Interest Rate Insensitivity of AI Investments

Unlike traditional business investments, Powell suggested that AI infrastructure spending operates largely independent of Federal Reserve monetary policy. "I don't think the spending that happens to build data centers all over the country is especially interest-sensitive," he stated, explaining that these investments are "based on longer-run assessments that this is an area where there's going to be a lot of investment that's going to drive higher productivity"

5

.This assessment proved accurate as tech giants continued aggressive spending despite rate considerations. Amazon CEO Andy Jassy confirmed the company will "continue to be very aggressive in investing capacity" due to strong demand, while Microsoft's CFO Amy Hood noted that despite tens of billions in recent spending, "we are not" catching up to demand

5

.Related Stories

Employment Concerns Amid AI Transformation

Despite the economic benefits of AI investment, Powell expressed growing concern about its impact on employment. He noted that "a significant number of companies" are announcing hiring freezes or layoffs, with executives frequently citing "AI and what it can do" as justification

4

. Amazon recently laid off 14,000 corporate employees, with projections suggesting this could reach 30,000 by 2026, while Meta cut 600 employees despite investing $14.3 billion in AI initiatives1

.

Source: Fortune

Powell acknowledged it's "too soon to tell" whether AI is contributing to layoffs but emphasized this as an area the Federal Reserve is "watching very carefully"

1

. The employment effects contribute to what Powell described as a "bifurcated economy," where high-income consumers continue spending while lower-income consumers tighten their belts1

.References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

Related Stories

Federal Reserve governors warn AI could trigger unemployment spike that monetary policy can't fix

18 Feb 2026•Policy and Regulation

AI Investment Surge Creates Economic Uncertainty as Fed Grapples with 'Bifurcated' Economy

11 Nov 2025•Business and Economy

AI's Impact on the Job Market: More Retraining Than Layoffs, For Now

05 Sept 2025•Business and Economy

Recent Highlights

1

Pentagon threatens Anthropic with Defense Production Act over AI military use restrictions

Policy and Regulation

2

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

3

Anthropic accuses Chinese AI labs of stealing Claude through 24,000 fake accounts

Policy and Regulation