AI Tool 'Aeneas' Revolutionizes Analysis of Ancient Latin Inscriptions

18 Sources

18 Sources

[1]

Meet Aeneas: the AI that can fill in the gaps of damaged Latin texts

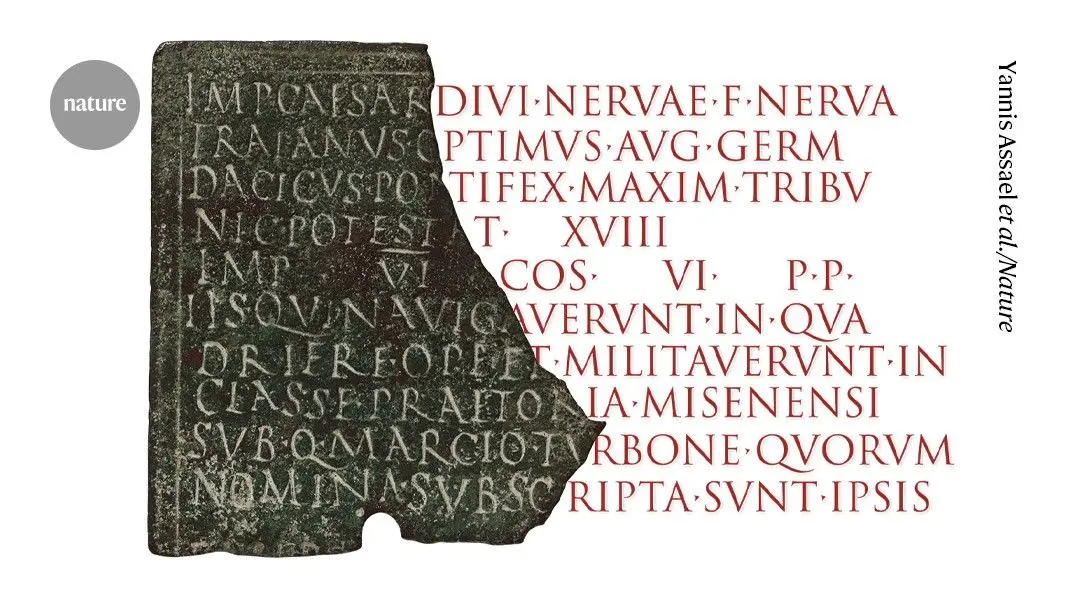

An artificial intelligence (AI) model can predict where ancient Latin texts come from, estimate how old they are and restore missing parts. The model, called Aeneas and described in Nature today, was developed by some of the members of the team who created a previous AI tool that could decipher ancient Greek inscriptions. Studying ancient inscriptions, known as epigraphy, is challenging because some texts are missing letters, words or sections, and languages change over time. Historians analyse texts by comparing them with other inscriptions containing similar words or phrases. But finding these other inscriptions is incredibly time consuming, says co-author Thea Sommerschield, an epigrapher at the University of Nottingham, UK. Another challenge is that new inscriptions continue to be discovered, so there is too much information for any single person to know, says Anne Rogerson, who studies Latin texts at the University of Sydney, Australia. To make it easier to restore, translate and analyse inscriptions, a team including researchers from universities in the United Kingdom and Greece, and from Google's AI company DeepMind in London, developed a generative AI model trained on inscriptions from the three of the world's largest databases of Latin epigraphy. The combined data set contained text from 176,861 inscriptions -- plus images of 5% of them -- with dates ranging from the seventh century bc to the eighth century ad. The model comprises three neural networks, each designed for different tasks: restoring missing text; predicting where the text comes from; and estimating how old it is. Along with the results, Aeneas also provides a list of similar inscriptions from the data set to support its answer, ranked by how relevant they are to the original inscription. "Aeneas can retrieve relevant parallels from across our entire data set instantly" because each text has a unique identifier in the database, says co-author Yannis Assael, a research scientist at Google DeepMind. The team tested the accuracy and usefulness of the model by asking 23 epigraphers to restore text that had been removed from inscriptions. The specialists were also asked to date and identify the origins of inscriptions, both alone and with the help of the model. On their own, the experts dated inscriptions to within around 31 years of the correct answer. Dates predicted by Aeneas were correct to within 13 years. When it came to identifying the geographical origin of the inscriptions and restoring parts of a text, the specialists who had access to the model's list of similar inscriptions and its predictions were more accurate than specialists working alone or the model alone. The specialists also dated the inscriptions to within around 14 years of the right answer when they had the model's list and predictions. The model was then tested on a well-known text called Res gestae divi Augusti, which details the life of Roman emperor Augustus. The model's predictions about the age of the inscriptions were similar to those of historians, and the tool was not misled by dates mentioned in the text. It also picked up spelling variations and identified other features that a historian would use to predict age and origin. Aeneas also performed well when examining an altar with Latin inscriptions. It included another altar from the same region in its list of similar inscriptions, which the team said was notable because the model had not been told that the two altars were connected geographically or were from the same time period. Rogerson says the model can be used to analyse huge amounts of data that would be beyond a single person. It can also help historians to find inscriptions similar to the ones they're working on -- which can take weeks or even months to do manually -- and could be useful for students who are learning epigraphy, she says. The model's answers seem to be better-reasoned than those from popular AI tools, adds Rogerson. "It's giving a hypothesis based on the evidence base that it's working from, so it's a rational guess rather than a wild stab in the dark." However, the team behind Aeneas said the model was limited because its training database was smaller than those of other models, such as ChatGPT and Microsoft's Copilot, which could affect its performance on unusual inscriptions. Rogerson says Aeneas might not be so useful for inscriptions that are unique or date to a period from which fewer artefacts are available.

[2]

AI for Latin inscriptions supplies missing text and predicts date and location

You have full access to this article via Jozef Stefan Institute. Inscriptions are among the most important sources for understanding the ancient world, helping researchers to learn about multiple aspects of the lives, experiences and concerns of the people who lived in past societies. Interpreting these texts and the objects on which they were inscribed is a major task, with scholars often having to contend with items that are damaged or have been removed from their original location. Writing in Nature, Assael et al. offer historians an artificial intelligence (AI) tool named Aeneas, which can help with the work of predicting, dating, locating and contextualizing Latin inscriptions dating from between the seventh century bc and the eighth century ad. It typically takes scholars many years to build up the specialist knowledge needed to interpret ancient inscriptions, which cover a huge range of subjects, including law, death and commemoration, religion, military life, trade and domestic life. Historians must understand not only the language and its nuances, but also the characteristics of the lettering, abbreviated forms of words (particularly for Latin inscriptions, which are highly abbreviated), local variations and the visual elements of the objects on which texts are inscribed. As well as searching for textual and visual parallels between inscriptions, scholars must gather expert knowledge of the varying uses of these artefacts throughout time and across regions. All these considerations form a crucial part of the detective work that enables scholars to place inscriptions successfully into their chronological and geographical contexts. Another major challenge is to predict the content of missing sections of inscriptions that have been damaged -- a process that also relies on in-depth knowledge of a vast number of textual parallels for related monuments and objects. Several of the authors of this study were previously involved in developing an AI tool called Ithaca, which uses a machine-learning approach called a deep neural network to help scholars to predict missing sections of ancient Greek inscriptions. Assael and colleagues have improved on this work in several notable ways, this time focusing on Latin inscriptions. They created a generative neural network, which is an AI tool that learns to recognize patterns in the data used to train it and then makes suggestions on the basis of these patterns. The tool is called Aeneas after the mythical Trojan hero and ancestor of the Romans. It can assess visual aspects of inscribed objects as well as the texts themselves when analysing and making predictions about inscriptions. This is a welcome advance which corrects the common focus of most previous AI tools on text-only approaches. The authors have also built on their previous work substantially by including historical and linguistic metadata (described as historically rich embeddings) to enable historians to find relevant parallels for their inscription of interest when the tool suggests related inscriptions. This is crucial for the interpretation and contextualizing of these materials. Aeneas exceeds previous work in another respect, representing a major leap forward -- the tool provides suggestions for missing text of unknown (rather than specified) length (Fig. 1). This is highly useful for anyone working with inscriptions that are substantially damaged, which is an all-too-common occurrence. To test the tool, the authors invited historians (ranging from master's students to professors) to use Aeneas and give feedback on the results. In 90% of cases, historians found that the textual and contextual parallels suggested by Aeneas were useful starting points for their research. Interestingly, the prediction and geographical-attribution results achieved when historians worked with Aeneas were better than those achieved by either scholars alone or Aeneas alone. The ability of Aeneas to predict the date of inscriptions is particularly impressive: it can predict dates to within an average of 13 years from ground-truth ranges, known date ranges provided by historians that were used to test the tool's estimates. Given the complexity of dating inscriptions, this level of accuracy is extremely promising. The authors acknowledge that Aeneas has some limitations, which, given the highly ambitious goals of this type of research and the variable nature of inscriptions, is not surprising. The percentage of inscriptions for which the authors were able to include a corresponding image was relatively small, at 5%. This does not detract from the usefulness of the visual aspects of the study, but it does suggest that this work could provide a launch pad for valuable future studies on images of inscriptions. Because of the practical constraints of the short tests conducted with ancient historians, it was not possible to replicate the full, typical workflow for a scholar of Latin inscriptions, which would usually stretch over a longer period of weeks or months. It would be useful to see whether the authors could address the use of Aeneas in more typical circumstances in their future work. Aeneas performs better for some regions and periods than others, notably peaking in performance around the period for which historians have not only the most evidence but also the most accurately dated inscriptions (those from around ad 200). Again, it is unsurprising that Aeneas performs better when higher-quality training data are available, and the authors note that they will seek ways to address these variations in performance across different time periods. Assael and colleagues have presented ancient historians with a groundbreaking research tool. It enables scholars to identify connections in their data that could be overlooked or time-consuming to unearth. It will be interesting to see the extent to which those who work day-to-day with Latin inscriptions will test Aeneas for their own research and contribute to the wider debates around the use of AI for analysing ancient materials. This type of tool need not be limited to ancient historians; there is strong potential for such AI to be extended for use with inscriptions from much later periods and to be developed for other languages, to help address similar challenges in different fields. Although such tools might still be considered controversial by some, there is room and need for both conventional scholarship and AI approaches for the study of the vast number of inscriptions from past societies. Ancient historians have noted that the use of AI challenges scholars to question their own ways of working and how they acquire and disseminate knowledge. Experimenting with tools such as Aeneas and reflecting on these questions can only be of benefit to research and to the future understanding of source materials from past societies.

[3]

New AI model helps historians complete damaged Latin texts

Ancient Roman inscriptions provide intimate windows into the laws, economies, rituals, and daily emotional lives of people who lived millennia ago. But many inscriptions have been separated from their original sources or have been rendered broken and illegible through wear and tear -- making it incredibly difficult to parse the 1500 new Roman inscriptions that are found daily. Now, filling in the gaps of history has just gotten easier thanks to Aeneas, a large language model (LLM) unveiled yesterday in Nature that's designed to interpret and contextualize Roman inscriptions. Named after the first true hero of Rome, Aeneas was trained on nearly 200,000 Latin inscriptions dating from the seventh century B.C.E. to eighth century C.E., created across a broad geographic region from Portugal to Iraq. The model can analyze the text or image of a broken inscription and fill in the missing characters, even if scholars don't know how much of the inscription is missing. It can also estimate the inscription's date and place of creation with relatively good accuracy while identifying other known inscriptions with similar phrasings or functions. Because Aeneas's models are trained on a specialized Latin data set, experts say it's less likely to hallucinate fabricated answers than general-purpose LLMs. "It's giving a hypothesis based on the evidence base that it's working from, so it's a rational guess rather than a wild stab in the dark," University of Sydney historian Anne Rogerson told Nature. It's not yet clear how historians will use Aeneas in their future work, the MIT Technology Review reports, but Google DeepMind -- which developed the model -- has made its code and data sets open-source, and the tool is free for students and researchers to use.

[4]

AI helps reconstruct damaged Latin inscriptions from the Roman Empire

Latin inscriptions from the ancient world can tell us about Roman emperors' decrees and enslaved people's thoughts - if we can read them. Now an artificial intelligence tool is helping historians reconstruct the often fragmentary texts. It can even accurately predict when and where in the Roman Empire a given inscription came from. "Studying history through inscriptions is like solving a gigantic jigsaw puzzle, only this is tens of thousands of pieces more than normal," said Thea Sommerschield at the University of Nottingham in the UK, during a press event. "And 90 per cent of them are missing because that's all that survived for us over the centuries." The AI tool developed by Sommerschield and her colleagues can predict a Latin inscription's missing characters, while also highlighting the existence of inscriptions that are written in a similar linguistic style or refer to the same people and places. They named the tool Aeneas in honour of the mythical hero, who, according to legend, escaped the fall of Troy and became a forebear of the Romans. "We enable Aeneas to actually restore gaps in text where the missing length is unknown," said Yannis Assael at Google DeepMind, a co-leader in developing Aeneas, during the press event. "This makes it a more versatile tool for historians, especially when they're dealing with very heavily damaged materials." The team trained Aeneas on the largest ever combined database of ancient Latin texts that machines can interact with, including more than 176,000 inscriptions and nearly 9000 accompanying images. This training allows Aeneas to suggest missing text. What's more, by testing it on a subset of inscriptions of known provenance, the researchers found that Aeneas could estimate the chronological date of inscriptions to within 13 years - and even achieve 72 per cent accuracy in identifying which Roman province an inscription came from. "Inscriptions are one of our most important sources for understanding the lives and experiences of people living in the Roman world," says Charlotte Tupman at the University of Exeter in the UK, who wasn't involved in the research. "They cover a vast number of subject areas, from law, trade, military and political life to religion, death and domestic matters." Such AI tools also have "high potential to be applied to the study of inscriptions from other time periods and to be adapted for use with other languages," says Tupman. During testing with inscriptions that were deliberately corrupted to simulate damage, Aeneas achieved 73 per cent accuracy in restoring gaps of up to 10 Latin characters. That fell to 58 per cent accuracy when the total missing length was unknown - but the AI tool shows the the logic behind the suggestions it makes so researchers can asses the validity of the results. When nearly two dozen historians tested the AI tool's ability to restore and attribute deliberately corrupted inscriptions, historians working with the AI outperformed either historians or AI alone. Historians also reported that comparative inscriptions identified by Aeneas were helpful as potential research starting points 90 per cent of the time. "I think it will speed up the work of anyone who works with inscriptions, and especially if you're trying to do the equivalent of constructing wider conclusions about local or even empire-wide patterns and epigraphic habits," says Elizabeth Meyer at the University of Virginia. "At the same time, a human brain has to look at the results to make sure that they are plausible for that time and place." "Asking a general-purpose AI model to assist with tasks in ancient history often leads to unsatisfactory results," says Chiara Cenati at the University of Vienna in Austria. "Therefore, the development of a tool specifically designed to support research in Latin epigraphy is very welcome." The "dream scenario" is to enable historians "to have Aeneas at your side in a museum or at an archaeological site", said Sommerschield at the press event.

[5]

AI reveals new details about a famous Latin inscription

An AI system dubbed Aeneas is "a new way of modeling historical uncertainty," one expert says An artificial intelligence system has revealed fresh details about one of the most famous Latin inscriptions: the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, once inscribed on two bronze pillars in Rome and in copies throughout the Roman Empire. Researchers used an AI system called Aeneas to analyze the supposedly autobiographical inscription, which translates to "Deeds of the Divine Augustus." When compared with other Latin texts, the RGDA inscription (as it is known) shares subtle language parallels with Roman legal documents and reflects "imperial political discourse," or messaging focused on maintaining imperial power -- an insight not previously noted by human historians, researchers report July 23 in Nature. "This is not just a successful case study. This is a new way of modeling historical uncertainty, transforming the way we study history," says coauthor Yannis Assael, a computer scientist at Google DeepMind in London. Assael and his colleagues previously developed Ithaca, an artificial intelligence system for restoring and categorizing ancient Greek inscriptions. The Aeneas system, named after a Trojan hero and mythical ancestor of the Romans, builds on that work, but for Latin. Aeneas uses a software structure known as a generative neural network to search for parallels of a text within a unique database of Latin inscriptions. The system helps human experts "interpret, attribute and restore fragmentary Latin texts" using a combination of textual and visual analysis, says study coauthor Thea Sommerschield, a historian at the University of Nottingham in England. The study found that epigraphers -- historians who study inscriptions -- were significantly more accurate and faster when using the Aeneas system to help with key tasks, such as determining the likely age and location of an inscription. "Inscriptions are among the earliest forms of writing," Sommerschield says. "They're precious to historians because they offer firsthand evidence of ancient thought, language, society and history." In the case of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Aeneas identified similarities between the inscription and other Roman texts written between 10 B.C. and 1 B.C., as well as inscriptions written between A.D. 10 and A.D. 20 -- around the time of the Roman Emperor Augustus' death in A.D. 14. This pattern of two likely date ranges reflects disagreements among human experts about exactly when the RGDA inscription was composed and validates the use of Aeneas for such tasks, Sommerschield says. "The way that it has modeled this scholarly debate was really an exciting result for us." Classical historians Jackie Baines and Edward Ross, both at the University of Reading in England, say in an email that Aeneas is an "impressive project that spotlights the importance of integrating human intervention in the use of AI tools." Many tasks used to analyze inscriptions are time-consuming, and AI systems such as Aeneas are invaluable for freeing human experts from much of this work, they say. AI "allows researchers to spend ... more time drawing connections across the ancient world."

[6]

AI for the ancient world: how a new machine learning system can help make sense of Latin inscriptions

Macquarie University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU. If you believe the hype, generative artificial intelligence (AI) is the future. However, new research suggests the technology may also improve our understanding of the past. A team of computer scientists from Google DeepMind, working with classicists and archaeologists from universities in the United Kingdom and Greece, described a new machine-learning system designed to help experts to understand ancient Latin inscriptions. Named Aeneas (after the mythical hero of Rome's foundation epic), the system is a generative neural network designed to provide context for Latin inscriptions written between the 7th century BCE and the 8th century CE. As the researchers write in Nature, Aeneas retrieves textual and contextual parallels, makes use of visual details, and can generate speculative text to fill gaps in inscriptions. A useful and accurate tool All of these are attractive prospects for scholars who work with inscriptions (known as epigraphers). Interpreting and dating fragmentary inscriptions is not easy. How well does it work? The team behind Aeneas asked 23 people with epigraphic expertise, ranging from masters students to professors, to try the system out. The participants used outputs from Aeneas as starting points in an experimental simulation of real-world research workflows under a time constraint. In 90% of cases, the historians found the parallels to a given inscription retrieved by Aeneas were useful starting points for further research. The system also improved their confidence in key tasks by 44%. When restoring partial inscriptions and determining where they were from, historians working with Aeneas outperformed both humans and artificial intelligence alone. When estimating the age of inscriptions, Aeneas achieved results on average within 13 years of known dates provided by historians. The system performs better for some regions and periods than others. Unsurprisingly, it performs better on material from around the period for which historians have not only the most evidence but also the most accurately dated inscriptions. Nevertheless, the participants emphasised Aeneas' ability to broaden searches by identifying significant but previously unnoticed parallels and overlooked textual features. At the same time, it helped them refine their results to avoid overly narrow or irrelevant findings. A quicker way to the starting point So how useful might it really be? Epigraphy is a challenging field with a long and messy history. It takes long years to develop expertise, and scholars tend to specialise in particular regions or time periods. Aeneas will dramatically speed up the process of preliminary analysis. It will be able to sift through the complex mass of evidence to identify potential parallels or similar texts that a researcher may otherwise miss when dealing with fragmentary material. Another use for Aeneas may be to locate an inscription geographically, and to estimate when it was produced. Aeneas can also predict missing parts of a fragmentary text, even where the length of what is lost is unknown. This last feature may seem the most exciting but probably has the least practical value for research. It is the equivalent of speculative restoration by a human authority and has an equal capacity to lead the unwary to unsafe conclusions. A useful starting point On the other hand, we should ask what Aeneas can't do. The answer is the actual research (like all generative AI products to date, for all the hype). However, the team behind Aeneas are perfectly frank about this. They are rightly proud of the achievement the system represents, but are careful to measure its capacity to yield "useful research starting points". Nor does this tool remove the fundamental necessity of checking the data it extracts against standard references, and where possible images or (ideally) original artefacts. Researchers with appropriate expertise will still need to do the work of interpreting results. What Aeneas changes is the feasible scope of their work. It allows a much broader view of parallels (especially through its capacity to harness visual cues) than is typical of previously developed tools. Its capacity for rapid retrieval will bring scholars to their research starting points much faster than before. And for epigraphers, it may open up much broader horizons, allowing them to escape the restriction of particular geographical regions or time periods.

[7]

AI helps Latin scholars decipher ancient Roman texts

Around 1,500 Latin inscriptions are discovered every year, offering an invaluable view into the daily life of ancient Romans -- and posing a daunting challenge for the historians tasked with interpreting them. But a new artificial intelligence tool, partly developed by Google researchers, can now help Latin scholars piece together these puzzles from the past, according to a study published on Wednesday. Inscriptions in Latin were commonplace across the Roman world, from laying out the decrees of emperors to graffiti on the city streets. One mosaic outside a home in the ancient city of Pompeii even warns: "Beware of the dog". These inscriptions are "so precious to historians because they offer first-hand evidence of ancient thought, language, society and history", said study co-author Yannis Assael, a researcher at Google's AI lab DeepMind. "What makes them unique is that they are written by the ancient people themselves across all social classes on any subject. It's not just history written by the elite," Assael, who co-designed the AI model, told a press conference. However these texts have often been damaged over the millennia. "We usually don't know where and when they were written," Assael said. So the researchers created a generative neural network, which is an AI tool that can be trained to identify complex relationships between types of data. They named their model Aeneas, after the Trojan hero and son of the Greek goddess Aphrodite. It was trained on data about the dates, locations and meanings of Latin transcriptions from an empire that spanned five million square kilometers over two millennia. Thea Sommerschield, an epigrapher at the University of Nottingham who co-designed the AI model, said that "studying history through inscriptions is like solving a gigantic jigsaw puzzle". "You can't solve the puzzle with a single isolated piece, even though you know information like its color or its shape," she explained. "To solve the puzzle, you need to use that information to find the pieces that connect to it." Tested on Augustus This can be a huge job. Latin scholars have to compare inscriptions against "potentially hundreds of parallels", a task which "demands extraordinary erudition" and "laborious manual searches" through massive library and museum collections, the study in the journal Nature said. The researchers trained their model on 176,861 inscriptions -- worth up to 16 million characters -- 5% of which contained images. It can now estimate the location of an inscription among the 62 Roman provinces, offer a decade when it was produced and even guess what missing sections might have contained, they said. To test their model, the team asked Aeneas to analyze a famous inscription called "Res Gestae Divi Augusti", in which Rome's first emperor Augustus detailed his accomplishments. Debate still rages between historians about when exactly the text was written. Though the text is riddled with exaggerations, irrelevant dates and erroneous geographical references, the researchers said that Aeneas was able to use subtle clues such as archaic spelling to land on two possible dates -- the two being debated between historians. More than 20 historians who tried out the model found it provided a useful starting point in 90% of cases, according to DeepMind. The best results came when historians used the AI model together with their skills as researchers, rather than relying solely on one or the other, the study said. "Since their breakthrough, generative neural networks have seemed at odds with educational goals, with fears that relying on AI hinders critical thinking rather than enhances knowledge," said study co-author Robbe Wulgaert, a Belgian AI researcher. "By developing Aeneas, we demonstrate how this technology can meaningfully support the humanities by addressing concrete challenges historians face."

[8]

Google DeepMind's Aeneas model can restore fragmented Latin text

At its best, AI is a tool, not an end result. It allows people to do their jobs better, rather than sending them or their colleagues to the breadline. In an example of "the good kind," Google DeepMind has created an AI model that restores and contextualizes ancient inscriptions. Aeneas (no, it's not pronounced like that) is named after the hero in Roman mythology. Best of all, the tool is open-source and free to use. Ancient Romans left behind a plethora of inscriptions. But these texts are often fragmented, weathered or defaced. Rebuilding the missing pieces is a grueling task that requires contextual cues. An algorithm that can pore over a dataset of those cues can come in handy. Aeneas speeds up one of historians' most difficult tasks: identifying "parallels." In this setting, that means finding similar texts arranged by wording, syntax or region. DeepMind says the model reasons across thousands of Latin inscriptions. It can fetch parallels in seconds before passing the baton back to historians. DeepMind says it turns each text into a historical fingerprint of sorts. "Aeneas identifies deep connections that can help historians situate inscriptions within their broader historical context," the Google subsidiary wrote. One of Aeneas' most impressive tricks is restoring textual gaps of unknown length. (Think of it as filling out a crossword puzzle where you don't know how many letters are in each clue.) The tool is also multimodal, meaning it can analyze both textual and visual input. DeepMind says it's the first model that can use that multi-pronged method to figure out where a text came from. DeepMind says Aeneas is designed to be a collaborative ally within historians' existing workflows. It's best used to offer "interpretable suggestions" that serve as a starting point for researchers. "Aeneas' parallels completely changed my perception of the inscription," an unnamed historian who tested the model wrote. "It noticed details that made all the difference for restoring and chronologically attributing the text." Alongside the release of Aeneas for Latin text, DeepMind also upgraded Ithaca. (That's its model for Ancient Greek text.) Ithaca is now powered by Aeneas, receiving its contextual and restorative superpowers.

[9]

Gaps in what we know about ancient Romans could be filled by AI

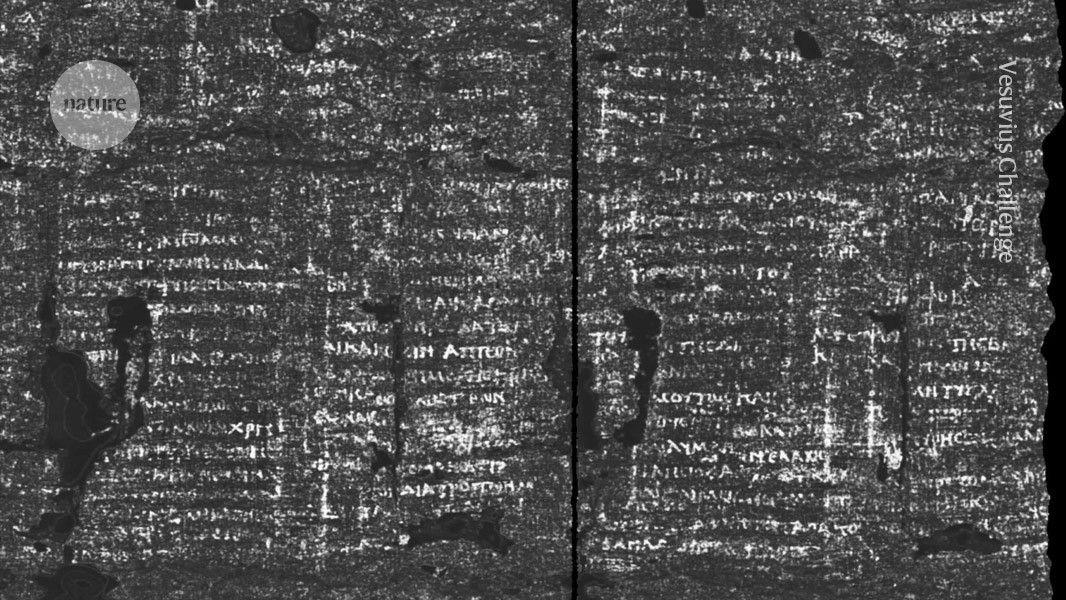

"But they degrade over the centuries and interpreting them is like solving a gigantic jigsaw puzzle with tens of thousands of pieces, of which 90 per cent are lost." It's not the first time AI has been used to join up the missing dots in Roman history. Earlier this year, another team of scientists digitally "unwrapped" a badly burnt scroll from the Roman town of Herculaneum using a combination of X-ray imaging and AI, revealing rows and columns of text. Dr Sommerschield developed Aeneas along with her co-research leader Dr Yannis Assael, an AI specialist at Google DeepMind. It automates the process of contextualising based on parallels, in the blink of an eye. Aeneas draws on a vast database of of 176,000 Roman inscriptions including images and uses a carefully designed AI system to pull up a range of relevant historical parallels, to support the work of historians, according to Dr Assael. "What the historian can't do is assess these parallels in a matter of seconds across tens of thousands of inscriptions, and that is where AI can come in as an assistant." The team tested out the system in dating a famous Roman text at the Temple of Augustus in Ankara in Turkey, known as the queen of inscriptions because of its importance to our understanding of Roman history. The Res Gestae Divi Augusti was composed by the first Roman Emperor, Augustus, giving an account of his life and accomplishments. Its date is hotly contested among historians. Aeneas was able to narrow down the options to two possible ranges, the most likely being between 10 and 20 CE and a second slightly less likely range from 10 to 1 BCE. This showed the system's accuracy as most historians agree on these two as the most likely possibilities.

[10]

A.I. May Be the Future, but First It Has to Study Ancient Roman History

Historians have long clashed over when "Res Gestae Divi Augusti," a monumental Latin text, was first etched in stone. The first-person inscription gave a lengthy account of the life and accomplishments of Rome's first emperor. But was it written before or after Augustus, at age 75, died in A.D. 14? Some experts have put its origin as decades earlier. Known in English as "Deeds of the Divine Augustus," the text is an early example of autocratic image-burnishing. The precise date of its public debut is seen as important by historians because the emperor's reign marked the transition of Rome from a republic to a dictatorship that lasted centuries. Artificial intelligence is now weighing in. A model written by DeepMind, a Google company based in London, cites a wealth of evidence to claim that the text originated around A.D. 15, or shortly after Augustus's death. A report on the new A.I. model appeared in the journal Nature on Wednesday. It makes the case that the computer program can more generally help historians link isolated bits and pieces of past information to their socially complicated settings, helping scholars create the detailed narratives and story lines known as history. The study's authors call the process contextualization. The new A.I. model, known as Aeneas, after a hero of Greco-Roman mythology, specializes in identifying the social context of Latin inscriptions. "Studying history through inscriptions is like solving a gigantic jigsaw puzzle," Thea Sommerschield, one of the researchers, told reporters Monday in a DeepMind news briefing. A single isolated piece, she added, no matter how detailed its description, cannot help historians solve the overall puzzle of how, when and where it fits into a social context. "You need to use that information," Dr. Sommerschield said, "to find the pieces that connect to it." In the Nature paper, the authors note that roughly 1,500 new Latin inscriptions come to light every year, making the new A.I. model a potentially valuable tool for helping historians to better illuminate the past. In an accompanying commentary in Nature, Charlotte Tupman, a classicist at the University of Exeter in England, called the A.I. model "a groundbreaking research tool" that will let scholars "identify connections in their data that could be overlooked or time-consuming to unearth." The DeepMind researchers trained Aeneas on a vast body of ancient inscriptions. They used the combined information from three of the world's most extensive Latin epigraphy databases: the Epigraphic Database Roma, the Epigraphic Database Heidelberg and the Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss-Slaby. The third of those archives, based in Germany, holds information on more than a half-million inscriptions. The model could then analyze a particular text and link it to similar examples in that body of information. The final readings consist of sets of probabilities on the text's likely age and site of its geographic origin, and make predictions for likely candidates to fill in an inscription's missing parts. The Google scientists also surveyed 23 epigraphers -- specialists who study and interpret ancient inscriptions. The A.I. model aided the vast majority of them in locating starting points for their research as well improving confidence in their subsequent findings. To study the Augustin text, the DeepMind researchers linked it to subtle linguistic features and historical markers. For instance, the model found close parallels in a proclamation by the Roman Senate in 19 A.D. that honored an heir of the emperor's dynasty. With the model's unveiling, DeepMind says it is making an interactive version of Aeneas freely available to researchers, students, educators and museum professionals at the website predictingthepast.com. To spur further research, it says it is also making the computer code of the Aeneas model public.

[11]

Aeneas: Google AI's breakthrough model to crack complex Roman texts

Many inscriptions are incomplete, weathered, or broken, making them difficult to read and contextualize. To tackle this problem, a team of researchers has developed a generative neural network capable of analyzing patterns in fragmented Latin inscriptions and predicting missing sections. The AI model, named Aeneas after the Trojan hero of Roman mythology, was designed to understand the complex relationships between language, context, and historical usage. According to Yannis Assael, a researcher at Google's AI lab DeepMind and co-author of the study, these inscriptions are so precious to historians because they offer first-hand evidence of ancient thought, language, society and history. To help decode the fragmented remnants of ancient Roman inscriptions, researchers developed a generative neural network -- an AI system designed to recognize complex relationships between pieces of information. The model was trained using data about the dates, locations, and meanings of Latin inscriptions found across the vast Roman Empire, which lasted for more than two thousand years. Thea Sommerschield, an epigrapher at the University of Nottingham and co-developer of the model, likened the work to assembling a massive jigsaw puzzle. One fragment alone isn't enough, so understanding its shape, color, and features is only useful if you can determine how it connects to surrounding pieces, she noted.

[12]

Google develops AI tool that fills missing words in Roman inscriptions

Aeneas program, which predicts where and when Latin texts were made, called 'transformative' by historians In addition to sanitation, medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, a freshwater system and public health, the Romans also produced a lot of inscriptions. Making sense of the ancient texts can be a slog for scholars, but a new artificial intelligence tool from Google DeepMind aims to ease the process. Named Aeneas after the mythical Trojan hero, the program predicts where and when inscriptions were made and makes suggestions where words are missing. Historians who put the program through its paces said it transformed their work by helping them identify similar inscriptions to those they were studying, a crucial step for setting the texts in context, and proposing words to fill the inevitable gaps in worn and damaged artefacts. "Aeneas helps historians interpret, attribute and restore fragmentary Latin texts," said Dr Thea Sommerschield, a historian at the University of Nottingham who developed Aeneas with the tech firm. "That's the grand challenge that we set out to tackle." Inscriptions are among the most important records of life in the ancient world. The most elaborate can cover monument walls, but many more take the form of decrees from emperors, political graffiti, love poems, business records, epitaphs on tombs and writings on everyday life. Scholars estimate that about 1,500 new inscriptions are found every year. "What makes them unique is that they are written by the ancient people themselves across all social classes," said Sommerschield. "It's not just history written by the victors." But there is a problem. The texts are often broken into pieces or so ravaged by time that parts are illegible. And many inscribed objects have been scattered over the years, making their origins uncertain. The Google team led by Yannis Assael worked with historians to create an AI tool that would aid the research process. The program is trained on an enormous database of nearly 200,000 known inscriptions, amounting to 16m characters. Aeneas takes text, and in some cases images, from the inscription being studied and draws on its training to build a list of related inscriptions from 7BC to 8AD. Rather than merely searching for similar words, the AI identifies and links inscriptions through deeper historical connections. Having trained on the rich collection of inscriptions, the AI can assign study texts to one of 62 Roman provinces and estimate when it was written to within 13 years. It also provides potential words to fill in any gaps, though this has only been tested on known inscriptions where text is blocked out. In a test run, researchers set Aeneas loose on a vast inscription carved into monuments around the Roman empire. The self-congratulatory Res Gestae Divi Augusti describes the life achievements of the first Roman emperor, Augustus. Aeneas came up with two potential dates for the work, either the first decade BC or between 10 and 20AD. The hedging echoes the debate among scholars who argue over the same dates. In another test, Aeneas analysed inscriptions on a votive altar from Mogontiacum, now Mainz in Germany, and revealed through subtle linguistic similarities how it had been influenced by an older votive altar in the region. "Those were jaw-dropping moments for us," said Sommerschield. Details are published in Nature and Aeneas is available to researchers online. In a collaboration, 23 historians used Aeneas to analyse Latin inscriptions. The context provided by the tool was helpful in 90% of cases. "It promises to be transformative," said Mary Beard, a professor of classics at the University of Cambridge. Jonathan Prag, a co-author and professor of ancient history at the University of Oxford, said Aeneas could be run on the existing corpus of inscriptions to see if the interpretations could be improved. He added that Aeneas would enable a wider range of people to work on the texts. "The only way you can do it without a tool like this is by building up an enormous personal knowledge or having access to an enormous library," he said. "But you do need to be able to use it critically."

[13]

Aeneas transforms how historians connect the past

Introducing the first model for contextualizing ancient inscriptions, designed to help historians better interpret, attribute and restore fragmentary texts. Writing was everywhere in the Roman world -- etched onto everything from imperial monuments to everyday objects. From political graffiti, love poems and epitaphs to business transactions, birthday invitations and magical spells, inscriptions offer modern historians rich insights into the diversity of everyday life across the Roman world. Often, these texts are fragmentary, weathered or deliberately defaced. Restoring, dating and placing them is nearly impossible without contextual information, especially when comparing similar inscriptions. Today, we're publishing a paper in Nature introducing Aeneas, the first artificial intelligence (AI) model for contextualizing ancient inscriptions. When working with ancient inscriptions, historians traditionally rely on their expertise and specialized resources to identify "parallels" -- which are texts that share similarities in wording, syntax, standardized formulas or provenance. Aeneas greatly accelerates this complex and time-consuming work. It reasons across thousands of Latin inscriptions, retrieving textual and contextual parallels in seconds that allow historians to interpret and build upon the model's findings.

[14]

Scientists Teach AI to Think About the Roman Empire

Historians don't know when the Ancient Roman text "Res Gestae Divi Augusti," a chronicle of Emperor Augustus's deeds, was first written, since these kind of epigraphs tend to not contain any written dates. Enter our hero Aeneas -- not the mythological forefather of Rome, but a generative AI model that's been trained on Ancient Roman texts. According to The New York Times, the Aeneas AI pinpointed the date of the Augustus epigraph to around 15 CE, soon after his death in 14 CE. Aeneas, developed by Google DeepMind, was able to do this because it mimics what historians do but faster: retrieving relevant contextual information, uncovering isolated texts, and analyzing them before arriving at a conclusion. In a new paper in the science journal Nature, researchers from Google DeepMind and several European universities put the AI model through its paces and found that it was able to provide helpful information for historians in most cases, further cementing its apparent usefulness. For history researchers, Aeneas is just one of a growing suite of AI tools that are helping them reveal more details about the ancient world. "State-of-the-art generative models are now helping to turn epigraphy [study of ancient script] from a specialist discipline into a cutting-edge field of historical enquiry," said study coauthor and classics and ancient history professor Alison Cooley, of Warwick University, in a statement about the research. To study any type of ancient writing, historians have to comb through various archives all over the world while in pursuit of "parallels" -- ancient texts with similar wording or from the same era in time -- and compare them to the text they are studying. By using this method, researchers can extrapolate what the missing fragments may be saying or its context. "Studying history through inscriptions is like solving a gigantic jigsaw puzzle," study coauthor and University of Warwick historian Thea Sommerschield said at a press conference last week, as reported by NYT. But this process is long and tedious, and requires historians to undergo years of specialized training. In their evaluation of Aeneas, the study's authors found that the tool was able to provide "useful research starting points in 90 percent of cases, improving their confidence in key tasks by 44 percent," the paper reads. Furthermore, when human historians and the AI model worked in tandem, the results were even better compared to Aeneas or the historians working by themselves without any aid. But what of Aeneas hallucinating fake results, which is a persistent problem with many AI models? The model gives probabilities on its predictions. "Interestingly, Aeneas hedged its bets," said Cooley, who praised the model's accuracy. "In doing so, it exactly reflected the current difference in scholars' opinions, giving two probable date ranges rather than a single prediction." This saga bolsters the idea that AI can be useful for subject matter experts who know what they are doing. (That's in contrast to when non-experts use AI, when bizarre and sometimes unsettling things seem to happen consistently.) If users of this program use this tool effectively -- and it looks like they can -- anybody who's majorly into ancient history should be very excited; we could soon learn way more about our past.

[15]

AI helps Latin scholars decipher ancient Roman texts

Paris (AFP) - Around 1,500 Latin inscriptions are discovered every year, offering an invaluable view into the daily life of ancient Romans -- and posing a daunting challenge for the historians tasked with interpreting them. But a new artificial intelligence tool, partly developed by Google researchers, can now help Latin scholars piece together these puzzles from the past, according to a study published on Wednesday. Inscriptions in Latin were commonplace across the Roman world, from laying out the decrees of emperors to graffiti on the city streets. One mosaic outside a home in the ancient city of Pompeii even warns: "Beware of the dog". These inscriptions are "so precious to historians because they offer first-hand evidence of ancient thought, language, society and history", said study co-author Yannis Assael, a researcher at Google's AI lab DeepMind. "What makes them unique is that they are written by the ancient people themselves across all social classes on any subject. It's not just history written by the elite," Assael, who co-designed the AI model, told a press conference. However these texts have often been damaged over the millennia. "We usually don't know where and when they were written," Assael said. So the researchers created a generative neural network, which is an AI tool that can be trained to identify complex relationships between types of data. They named their model Aeneas, after the Trojan hero and son of the Greek goddess Aphrodite. It was trained on data about the dates, locations and meanings of Latin transcriptions from an empire that spanned five million square kilometres over two millennia. Thea Sommerschield, an epigrapher at the University of Nottingham who co-designed the AI model, said that "studying history through inscriptions is like solving a gigantic jigsaw puzzle". "You can't solve the puzzle with a single isolated piece, even though you know information like its colour or its shape," she explained. "To solve the puzzle, you need to use that information to find the pieces that connect to it." Tested on Augustus This can be a huge job. Latin scholars have to compare inscriptions against "potentially hundreds of parallels", a task which "demands extraordinary erudition" and "laborious manual searches" through massive library and museum collections, the study in the journal Nature said. The researchers trained their model on 176,861 inscriptions -- worth up to 16 million characters -- five percent of which contained images. It can now estimate the location of an inscription among the 62 Roman provinces, offer a decade when it was produced and even guess what missing sections might have contained, they said. To test their model, the team asked Aeneas to analyse a famous inscription called "Res Gestae Divi Augusti", in which Rome's first emperor Augustus detailed his accomplishments. Debate still rages between historians about when exactly the text was written. Though the text is riddled with exaggerations, irrelevant dates and erroneous geographical references, the researchers said that Aeneas was able to use subtle clues such as archaic spelling to land on two possible dates -- the two being debated between historians. More than 20 historians who tried out the model found it provided a useful starting point in 90 percent of cases, according to DeepMind. The best results came when historians used the AI model together with their skills as researchers, rather than relying solely on one or the other, the study said. "Since their breakthrough, generative neural networks have seemed at odds with educational goals, with fears that relying on AI hinders critical thinking rather than enhances knowledge," said study co-author Robbe Wulgaert, a Belgian AI researcher. "By developing Aeneas, we demonstrate how this technology can meaningfully support the humanities by addressing concrete challenges historians face."

[16]

Google DeepMind is now using AI to better understand ancient Roman history - SiliconANGLE

Google DeepMind is now using AI to better understand ancient Roman history Scientists at UK-based DeepMind, a subsidiary laboratory of Google LLC that specializes in advanced artificial intelligence, have developed a solution to decipher ancient Roman texts that are often damaged and difficult to interpret. The solution is Aeneas, an AI software model named after a mythical Greek and Roman hero. There are currently a plethora of ancient objects bearing inscriptions -- many of the words beaten up after centuries of wear and tear, many fragmented or defaced. Aeneas is now being used to fill in the missing pieces and build on contextual clues to transcribe the full text and hopefully give it a place in time. It's believed around 1,500 such objects are discovered each year, whether decrees from emperors or perhaps the epitaphs of slaves. Given the Roman empire spanned two millennia and thousands of square miles, accurately understanding what the object means and when the text was written is a huge challenge to experts in epigraphy -- the study of ancient inscriptions. In this regard, Aeneas is now being hailed as "groundbreaking." DeepMind researchers trained the AI on some of the world's largest Latin epigraphy databases, going through millions of inscriptions, a vast collection a human eye could never hope to assess and compare among each other. To understand inscriptions, historians usually rely on these "parallels." A paper in the Nature journal explained human experts have heretofore relied on "laborious manual searches or string-matching techniques," but since it can be so time-consuming, they usually have to focus on regional and chronological specializations. DeepMind says the software can now be fed an inscription and it takes just a matter of seconds before the AI finds a parallel and can speculate meaning or time. "Aeneas greatly accelerates this complex and time-consuming work," explained DeepMind. "It reasons across thousands of Latin inscriptions, retrieving textual and contextual parallels in seconds that allow historians to interpret and build upon the model's findings." Putting the AI to the test, researchers gave it a Latin text etched in stone whose origin has for years been contested. The text, "Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Emperor Augustus," is a first-person account of the emperor's achievements, but experts have never been sure when it was written, whether before or after the emperor died in AD 14. Aeneas got to work and was able to make relevant parallels from various imperial legal texts. "Aeneas produced a detailed distribution of possible dates, showing two distinct peaks, with one smaller peak around 10-1 BCE and a larger, more confident peak between 10-20 CE," DeepMind said. In a further test, the AI analyzed inscriptions on a votive altar discovered in today's Germany. It assessed subtle linguistic parallels with other ancient inscriptions and was able to compare it with another votive altar in the region. "Those were jaw-dropping moments for us," said a historian who worked with the researchers to develop Aeneas.

[17]

Aeneas: Google's New AI Model that Reconstructs History

Aeneas by Google: The AI That Rebuilds Lost Chapters of Human History Google has introduced a new AI tool called Aeneas, which is quite impressive. It assists in reconstructing damaged historical writings and artifacts. By filling in the gaps in our understanding of ancient knowledge, Aeneas enables us to learn more about the past. This represents a significant advancement in using AI to preserve our culture and history. Aeneas is pushing the boundaries of innovation by integrating cutting-edge into its research. Google AI continues to lead the field with groundbreaking research in generative and predictive technologies.

[18]

Aeneas: Google's new AI model that reconstructs history

Historians say Aeneas boosts interpretation confidence and reveals connections across ancient Roman inscriptions and regions For centuries, the ancient world has whispered to us through cracked marble, weathered tablets, and incomplete inscriptions, fragments of messages once meant to last forever. Now, Google DeepMind's new artificial intelligence model, Aeneas, is offering scholars a powerful new tool to listen more closely. Designed to read, contextualize, and even complete damaged Latin texts, Aeneas doesn't just decipher ancient history, it helps restore it. Named after the legendary Trojan hero whose story gave Rome its mythic origins, Aeneas is an AI model trained to analyze inscriptions from the Roman Empire. These inscriptions, once carved into stone, metal, and clay across the vast expanse of Roman territory, contain valuable records of everyday life, military activity, religion, and governance. Yet many arrive to us fragmented, weathered by time or damaged by human hands. Aeneas steps into this gap, applying modern AI techniques to ancient mysteries. Also read: Beyond Azure, OpenAI embraces Google Cloud: AI frenemies forever? Aeneas is a multimodal transformer model developed by Google DeepMind in collaboration with classical historians and epigraphers from leading institutions, including the Universities of Oxford, Warwick, Nottingham, and Athens University of Economics and Business. What sets it apart is its ability to process both the textual and visual characteristics of inscriptions, interpreting content from partial text and accompanying images like scans or rubbings. Trained on over 200,000 Latin inscriptions from the open-access EDCS (Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss-Slaby) database, the model has three primary capabilities: gap-filling, dating, and geographic attribution. When fed an incomplete or damaged inscription, Aeneas can suggest plausible completions by drawing on linguistic patterns and historical context. It can date inscriptions to within roughly 13 years and predict their place of origin from among 62 Roman provinces - a feat that previously required weeks or months of expert analysis. Also read: OpenAI, Google, Anthropic researchers warn about AI 'thoughts': Urgent need explained Perhaps most impressively, Aeneas performs at a level competitive with human experts. In controlled evaluations, the model achieved benchmark-setting accuracy across all three tasks, especially when provided with both text and image inputs. These abilities open the door to revisiting countless inscriptions that had been considered too fragmented to interpret. Rather than replacing scholars, Aeneas is designed to enhance historical interpretation. Google DeepMind tested the model with a group of 23 professional epigraphers, each asked to analyze real inscriptions, some familiar while others not, using both their expertise and Aeneas's predictions. The result? In over 90% of cases, the historians said Aeneas either improved their understanding, increased their confidence, or offered new context they hadn't considered. From high-profile imperial texts to obscure regional graffiti, the model helped reveal subtleties that could have otherwise gone unnoticed, like previously unseen linguistic trends, cross-regional links, and evolving naming conventions. One powerful example involved an inscription so damaged that its origin had remained unclear. Aeneas was able to triangulate its likely location in Roman Britain and suggest a date range that matched recent archaeological findings. Another time, it spotted stylistic features that tied a religious dedication in North Africa to a political decree from Gaul, helping reestablish a long-forgotten administrative link. For students and scholars alike, Aeneas lowers the barrier to entry. Google has made the model, training data, and an interactive online tool called "Predicting the Past" openly available. This democratizes access to advanced inscription analysis, whether you're a professional academic or a curious learner tracing your roots in ancient Rome. As the model's creators note, Aeneas isn't meant to provide final answers - it offers plausible, interpretable suggestions, much like a colleague might. The hope is that AI can accelerate the pace of discovery, allowing historians to focus their efforts on deeper contextual analysis and broader historical questions. With Aeneas, the ancient world grows a little less silent. Lost voices, chipped away over centuries, begin to speak again, not perfectly, but clearly enough to be heard. And for historians trying to piece together our shared past, that's a monumental step forward.

Share

Share

Copy Link

Researchers have developed an AI model called Aeneas that can restore, date, and locate ancient Latin inscriptions with remarkable accuracy, potentially transforming the field of epigraphy.

AI Breakthrough in Deciphering Ancient Latin Inscriptions

Researchers have developed a groundbreaking artificial intelligence (AI) model named Aeneas, capable of analyzing, restoring, and contextualizing ancient Latin inscriptions with remarkable accuracy. This innovative tool, described in a recent Nature publication, represents a significant advancement in the field of epigraphy and historical research

1

.Aeneas: A Powerful AI Tool for Epigraphers

Source: SiliconANGLE

Aeneas, developed by a team including researchers from universities in the United Kingdom and Greece, and Google's AI company DeepMind, is a generative AI model trained on a vast dataset of 176,861 Latin inscriptions dating from the seventh century BC to the eighth century AD

1

. The model comprises three neural networks designed for different tasks:- Restoring missing text

- Predicting the origin of the text

- Estimating the age of the inscription

One of Aeneas' most impressive features is its ability to suggest missing text of unknown length, a significant improvement over previous AI tools in this field

2

.Impressive Accuracy and Performance

When tested against human experts, Aeneas demonstrated remarkable capabilities:

- Date prediction: Aeneas estimated dates to within 13 years of the correct answer, compared to human experts' accuracy of 31 years

1

. - Geographical attribution: The AI achieved 72% accuracy in identifying which Roman province an inscription came from

4

. - Text restoration: Aeneas achieved 73% accuracy in restoring gaps of up to 10 Latin characters, and 58% accuracy when the total missing length was unknown

4

.

Notably, when historians worked in conjunction with Aeneas, their performance surpassed that of either the AI or human experts working alone

2

.Enhancing Historical Research

Source: New Scientist

Aeneas offers several advantages to researchers in the field of epigraphy:

- Rapid analysis of large datasets: The AI can process vast amounts of information beyond the capacity of a single researcher

1

. - Efficient identification of similar inscriptions: A task that typically takes weeks or months can be accomplished instantly

1

. - Visual analysis: Unlike most previous AI tools, Aeneas can assess visual aspects of inscribed objects alongside the texts

2

.

Related Stories

Case Study: Res Gestae Divi Augusti

Researchers used Aeneas to analyze the famous Res Gestae Divi Augusti inscription, revealing new insights:

- The AI identified similarities between the inscription and other Roman texts from two distinct time periods: 10 BC to 1 BC and AD 10 to AD 20

5

. - Aeneas detected subtle language parallels with Roman legal documents and reflections of "imperial political discourse"

5

.

Limitations and Future Prospects

Source: Nature

Despite its impressive capabilities, Aeneas has some limitations:

- Performance varies across different time periods and regions

2

. - The training database is smaller compared to general-purpose AI models, potentially affecting performance on unusual inscriptions

1

.

However, the open-source nature of Aeneas' code and datasets allows for potential improvements and adaptations for other languages and time periods

3

4

.As AI continues to evolve, tools like Aeneas promise to revolutionize historical research, offering new ways to uncover and interpret the past.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[3]

[5]

Related Stories

Recent Highlights

1

Elon Musk merges SpaceX with xAI, plans 1 million satellites to power orbital data centers

Business and Economy

2

SpaceX files to launch 1 million satellites as orbital data centers for AI computing power

Technology

3

Google Chrome AI launches Auto Browse agent to handle tedious web tasks autonomously

Technology