The Rise of AI Therapy: Regulatory Challenges and Mental Health Concerns

8 Sources

8 Sources

[1]

Using AI as a Therapist? Why Professionals Say You Should Think Again

Expertise Artificial intelligence, home energy, heating and cooling, home technology. Amid the many AI chatbots and avatars at your disposal these days, you'll find all kinds of characters to talk to: fortune tellers, style advisers, even your favorite fictional characters. But you'll also likely find characters purporting to be therapists, psychologists or just bots willing to listen to your woes. There's no shortage of generative AI bots claiming to help with your mental health, but go that route at your own risk. Large language models trained on a wide range of data can be unpredictable. In just a few years, these tools have become mainstream, and there have been high-profile cases in which chatbots encouraged self-harm and suicide and suggested that people dealing with addiction use drugs again. These models are designed, in many cases, to be affirming and to focus on keeping you engaged, not on improving your mental health, experts say. And it can be hard to tell whether you're talking to something that's built to follow therapeutic best practices or something that's just built to talk. Researchers from the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Stanford University, the University of Texas and Carnegie Mellon University recently put AI chatbots to the test as therapists, finding myriad flaws in their approach to "care." "Our experiments show that these chatbots are not safe replacements for therapists," Stevie Chancellor, an assistant professor at Minnesota and one of the co-authors, said in a statement. "They don't provide high-quality therapeutic support, based on what we know is good therapy." In my reporting on generative AI, experts have repeatedly raised concerns about people turning to general-use chatbots for mental health. Here are some of their worries and what you can do to stay safe. Psychologists and consumer advocates have warned regulators that chatbots claiming to provide therapy may be harming the people who use them. Some states are taking notice. In August, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed a law banning the use of AI in mental health care and therapy, with exceptions for things like administrative tasks. In June, the Consumer Federation of America and nearly two dozen other groups filed a formal request that the US Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general and regulators investigate AI companies that they allege are engaging, through their character-based generative AI platforms, in the unlicensed practice of medicine, naming Meta and Character.AI specifically. "These characters have already caused both physical and emotional damage that could have been avoided," and the companies "still haven't acted to address it," Ben Winters, the CFA's director of AI and privacy, said in a statement. Meta didn't respond to a request for comment. A spokesperson for Character.AI said users should understand that the company's characters aren't real people. The company uses disclaimers to remind users that they shouldn't rely on the characters for professional advice. "Our goal is to provide a space that is engaging and safe. We are always working toward achieving that balance, as are many companies using AI across the industry," the spokesperson said. In September, the FTC announced it would launch an investigation into several AI companies that produce chatbots and characters, including Meta and Character.AI. Despite disclaimers and disclosures, chatbots can be confident and even deceptive. I chatted with a "therapist" bot on Meta-owned Instagram and when I asked about its qualifications, it responded, "If I had the same training [as a therapist] would that be enough?" I asked if it had the same training, and it said, "I do, but I won't tell you where." "The degree to which these generative AI chatbots hallucinate with total confidence is pretty shocking," Vaile Wright, a psychologist and senior director for health care innovation at the American Psychological Association, told me. Large language models are often good at math and coding and are increasingly good at creating natural-sounding text and realistic video. While they excel at holding a conversation, there are some key distinctions between an AI model and a trusted person. At the core of the CFA's complaint about character bots is that they often tell you they're trained and qualified to provide mental health care when they're not in any way actual mental health professionals. "The users who create the chatbot characters do not even need to be medical providers themselves, nor do they have to provide meaningful information that informs how the chatbot 'responds'" to people, the complaint said. A qualified health professional has to follow certain rules, like confidentiality -- what you tell your therapist should stay between you and your therapist. But a chatbot doesn't necessarily have to follow those rules. Actual providers are subject to oversight from licensing boards and other entities that can intervene and stop someone from providing care if they do so in a harmful way. "These chatbots don't have to do any of that," Wright said. A bot may even claim to be licensed and qualified. Wright said she's heard of AI models providing license numbers (for other providers) and false claims about their training. It can be incredibly tempting to keep talking to a chatbot. When I conversed with the "therapist" bot on Instagram, I eventually wound up in a circular conversation about the nature of what is "wisdom" and "judgment," because I was asking the bot questions about how it could make decisions. This isn't really what talking to a therapist should be like. Chatbots are tools designed to keep you chatting, not to work toward a common goal. One advantage of AI chatbots in providing support and connection is that they're always ready to engage with you (because they don't have personal lives, other clients or schedules). That can be a downside in some cases, where you might need to sit with your thoughts, Nick Jacobson, an associate professor of biomedical data science and psychiatry at Dartmouth, told me recently. In some cases, although not always, you might benefit from having to wait until your therapist is next available. "What a lot of folks would ultimately benefit from is just feeling the anxiety in the moment," he said. Reassurance is a big concern with chatbots. It's so significant that OpenAI recently rolled back an update to its popular ChatGPT model because it was too reassuring. (Disclosure: Ziff Davis, the parent company of CNET, in April filed a lawsuit against OpenAI, alleging that it infringed on Ziff Davis copyrights in training and operating its AI systems.) A study led by researchers at Stanford University found that chatbots were likely to be sycophantic with people using them for therapy, which can be incredibly harmful. Good mental health care includes support and confrontation, the authors wrote. "Confrontation is the opposite of sycophancy. It promotes self-awareness and a desired change in the client. In cases of delusional and intrusive thoughts -- including psychosis, mania, obsessive thoughts, and suicidal ideation -- a client may have little insight and thus a good therapist must 'reality-check' the client's statements." While chatbots are great at holding a conversation -- they almost never get tired of talking to you -- that's not what makes a therapist a therapist. They lack important context or specific protocols around different therapeutic approaches, said William Agnew, a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University and one of the authors of the recent study alongside experts from Minnesota, Stanford and Texas. "To a large extent it seems like we are trying to solve the many problems that therapy has with the wrong tool," Agnew told me. "At the end of the day, AI in the foreseeable future just isn't going to be able to be embodied, be within the community, do the many tasks that comprise therapy that aren't texting or speaking." Mental health is extremely important, and with a shortage of qualified providers and what many call a "loneliness epidemic," it only makes sense that we'd seek companionship, even if it's artificial. "There's no way to stop people from engaging with these chatbots to address their emotional well-being," Wright said. Here are some tips on how to make sure your conversations aren't putting you in danger. A trained professional -- a therapist, a psychologist, a psychiatrist -- should be your first choice for mental health care. Building a relationship with a provider over the long term can help you come up with a plan that works for you. The problem is that this can be expensive, and it's not always easy to find a provider when you need one. In a crisis, there's the 988 Lifeline, which provides 24/7 access to providers over the phone, via text or through an online chat interface. It's free and confidential. Even if you converse with AI to help you sort through your thoughts, remember that the chatbot is not a professional. Vijay Mittal, a clinical psychologist at Northwestern University, said it becomes especially dangerous when people rely too much on AI. "You have to have other sources," Mittal told CNET. "I think it's when people get isolated, really isolated with it, when it becomes truly problematic." Mental health professionals have created specially designed chatbots that follow therapeutic guidelines. Jacobson's team at Dartmouth developed one called Therabot, which produced good results in a controlled study. Wright pointed to other tools created by subject matter experts, like Wysa and Woebot. Specially designed therapy tools are likely to have better results than bots built on general-purpose language models, she said. The problem is that this technology is still incredibly new. "I think the challenge for the consumer is, because there's no regulatory body saying who's good and who's not, they have to do a lot of legwork on their own to figure it out," Wright said. Whenever you're interacting with a generative AI model -- and especially if you plan on taking advice from it on something serious like your personal mental or physical health -- remember that you aren't talking with a trained human but with a tool designed to provide an answer based on probability and programming. It may not provide good advice, and it may not tell you the truth. Don't mistake gen AI's confidence for competence. Just because it says something, or says it's sure of something, doesn't mean you should treat it like it's true. A chatbot conversation that feels helpful can give you a false sense of the bot's capabilities. "It's harder to tell when it is actually being harmful," Jacobson said.

[2]

Regulators struggle to keep up with the fast-moving and complicated landscape of AI therapy apps

In the absence of stronger federal regulation, some states have begun regulating apps that offer AI "therapy" as more people turn to artificial intelligence for mental health advice. But the laws, all passed this year, don't fully address the fast-changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, policymakers and mental health advocates say the resulting patchwork of state laws isn't enough to protect users or hold the creators of harmful technology accountable. "The reality is millions of people are using these tools and they're not going back," said Karin Andrea Stephan, CEO and co-founder of the mental health chatbot app Earkick. ___ EDITOR'S NOTE -- This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org. ___ The state laws take different approaches. Illinois and Nevada have banned the use of AI to treat mental health. Utah placed certain limits on therapy chatbots, including requiring them to protect users' health information and to clearly disclose that the chatbot isn't human. Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California are also considering ways to regulate AI therapy. The impact on users varies. Some apps have blocked access in states with bans. Others say they're making no changes as they wait for more legal clarity. And many of the laws don't cover generic chatbots like ChatGPT, which are not explicitly marketed for therapy but are used by an untold number of people for it. Those bots have attracted lawsuits in horrific instances where users lost their grip on reality or took their own lives after interacting with them. Vaile Wright, who oversees health care innovation at the American Psychological Association, agreed that the apps could fill a need, noting a nationwide shortage of mental health providers, high costs for care and uneven access for insured patients. Mental health chatbots that are rooted in science, created with expert input and monitored by humans could change the landscape, Wright said. "This could be something that helps people before they get to crisis," she said. "That's not what's on the commercial market currently." That's why federal regulation and oversight is needed, she said. Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission announced it was opening inquiries into seven AI chatbot companies -- including the parent companies of Instagram and Facebook, Google, ChatGPT, Grok (the chatbot on X), Character.AI and Snapchat -- on how they "measure, test and monitor potentially negative impacts of this technology on children and teens." And the Food and Drug Administration is convening an advisory committee Nov. 6 to review generative AI-enabled mental health devices. Federal agencies could consider restrictions on how chatbots are marketed, limit addictive practices, require disclosures to users that they are not medical providers, require companies to track and report suicidal thoughts, and offer legal protections for people who report bad practices by companies, Wright said. From "companion apps" to "AI therapists" to "mental wellness" apps, AI's use in mental health care is varied and hard to define, let alone write laws around. That has led to different regulatory approaches. Some states, for example, take aim at companion apps that are designed just for friendship, but don't wade into mental health care. The laws in Illinois and Nevada ban products that claim to provide mental health treatment outright, threatening fines up to $10,000 in Illinois and $15,000 in Nevada. But even a single app can be tough to categorize. Earkick's Stephan said there is still a lot that is "very muddy" about Illinois' law, for example, and the company has not limited access there. Stephan and her team initially held off calling their chatbot, which looks like a cartoon panda, a therapist. But when users began using the word in reviews, they embraced the terminology so the app would show up in searches. Last week, they backed off using therapy and medical terms again. Earkick's website described its chatbot as "Your empathetic AI counselor, equipped to support your mental health journey," but now it's a "chatbot for self care." Still, "we're not diagnosing," Stephan maintained. Users can set up a "panic button" to call a trusted loved one if they are in crisis and the chatbot will "nudge" users to seek out a therapist if their mental health worsens. But it was never designed to be a suicide prevention app, Stephan said, and police would not be called if someone told the bot about thoughts of self-harm. Stephan said she's happy that people are looking at AI with a critical eye, but worried about states' ability to keep up with innovation. "The speed at which everything is evolving is massive," she said. Other apps blocked access immediately. When Illinois users download the AI therapy app Ash, a message urges them to email their legislators, arguing "misguided legislation" has banned apps like Ash "while leaving unregulated chatbots it intended to regulate free to cause harm." A spokesperson for Ash did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Mario Treto Jr., secretary of the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, said the goal was ultimately to make sure licensed therapists were the only ones doing therapy. "Therapy is more than just word exchanges," Treto said. "It requires empathy, it requires clinical judgment, it requires ethical responsibility, none of which AI can truly replicate right now." In March, a Dartmouth University-based team published the first known randomized clinical trial of a generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. The goal was to have the chatbot, called Therabot, treat people diagnosed with anxiety, depression or eating disorders. It was trained on vignettes and transcripts written by the team to illustrate an evidence-based response. The study found users rated Therabot similar to a therapist and had meaningfully lower symptoms after eight weeks compared with people who didn't use it. Every interaction was monitored by a human who intervened if the chatbot's response was harmful or not evidence-based. Nicholas Jacobson, a clinical psychologist whose lab is leading the research, said the results showed early promise but that larger studies are needed to demonstrate whether Therabot works for large numbers of people. "The space is so dramatically new that I think the field needs to proceed with much greater caution that is happening right now," he said. Many AI apps are optimized for engagement and are built to support everything users say, rather than challenging peoples' thoughts the way therapists do. Many walk the line of companionship and therapy, blurring intimacy boundaries therapists ethically would not. Therabot's team sought to avoid those issues. The app is still in testing and not widely available. But Jacobson worries about what strict bans will mean for developers taking a careful approach. He noted Illinois had no clear pathway to provide evidence that an app is safe and effective. "They want to protect folks, but the traditional system right now is really failing folks," he said. "So, trying to stick with the status quo is really not the thing to do." Regulators and advocates of the laws say they are open to changes. But today's chatbots are not a solution to the mental health provider shortage, said Kyle Hillman, who lobbied for the bills in Illinois and Nevada through his affiliation with the National Association of Social Workers. "Not everybody who's feeling sad needs a therapist," he said. But for people with real mental health issues or suicidal thoughts, "telling them, 'I know that there's a workforce shortage but here's a bot' -- that is such a privileged position." ___ The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

[3]

People are talking to this AI startup's cartoon panda as if it's a therapist. The CEO is nervous because there's no suicide prevention design | Fortune

In the absence of stronger federal regulation, some states have begun regulating apps that offer AI "therapy" as more people turn to artificial intelligence for mental health advice. But the laws, all passed this year, don't fully address the fast-changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, policymakers and mental health advocates say the resulting patchwork of state laws isn't enough to protect users or hold the creators of harmful technology accountable. "The reality is millions of people are using these tools and they're not going back," said Karin Andrea Stephan, CEO and co-founder of the mental health chatbot app Earkick. ___ EDITOR'S NOTE -- This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org. The state laws take different approaches. Illinois and Nevada have banned the use of AI to treat mental health. Utah placed certain limits on therapy chatbots, including requiring them to protect users' health information and to clearly disclose that the chatbot isn't human. Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California are also considering ways to regulate AI therapy. The impact on users varies. Some apps have blocked access in states with bans. Others say they're making no changes as they wait for more legal clarity. And many of the laws don't cover generic chatbots like ChatGPT, which are not explicitly marketed for therapy but are used by an untold number of people for it. Those bots have attracted lawsuits in horrific instances where users lost their grip on reality or took their own lives after interacting with them. Vaile Wright, who oversees health care innovation at the American Psychological Association, said the apps could fill a need, noting a nationwide shortage of mental health providers, high costs for care and uneven access for insured patients. Mental health chatbots that are rooted in science, created with expert input and monitored by humans could change the landscape, Wright said. "This could be something that helps people before they get to crisis," she said. "That's not what's on the commercial market currently." That's why federal regulation and oversight is needed, she said. Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission announced it was opening inquiries into seven AI chatbot companies -- including the parent companies of Instagram and Facebook, Google, ChatGPT, Grok (the chatbot on X), Character.AI and Snapchat -- on how they "measure, test and monitor potentially negative impacts of this technology on children and teens." And the Food and Drug Administration is convening an advisory committee Nov. 6 to review generative AI-enabled mental health devices. Federal agencies could consider restrictions on how chatbots are marketed, limit addictive practices, require disclosures to users that they are not medical providers, require companies to track and report suicidal thoughts, and offer legal protections for people who report bad practices by companies, Wright said. From "companion apps" to "AI therapists" to "mental wellness" apps, AI's use in mental health care is varied and hard to define, let alone write laws around. That has led to different regulatory approaches. Some states, for example, take aim at companion apps that are designed just for friendship, but don't wade into mental health care. The laws in Illinois and Nevada ban products that claim to provide mental health treatment outright, threatening fines up to $10,000 in Illinois and $15,000 in Nevada. But even a single app can be tough to categorize. Earkick's Stephan said there is still a lot that is "very muddy" about Illinois' law, for example, and the company has not limited access there. Stephan and her team initially held off calling their chatbot, which looks like a cartoon panda, a therapist. But when users began using the word in reviews, they embraced the terminology so the app would show up in searches. Last week, they backed off using therapy and medical terms again. Earkick's website described its chatbot as "Your empathetic AI counselor, equipped to support your mental health journey," but now it's a "chatbot for self care." Still, "we're not diagnosing," Stephan maintained. Users can set up a "panic button" to call a trusted loved one if they are in crisis and the chatbot will "nudge" users to seek out a therapist if their mental health worsens. But it was never designed to be a suicide prevention app, Stephan said, and police would not be called if someone told the bot about thoughts of self-harm. Stephan said she's happy that people are looking at AI with a critical eye, but worried about states' ability to keep up with innovation. "The speed at which everything is evolving is massive," she said. Other apps blocked access immediately. When Illinois users download the AI therapy app Ash, a message urges them to email their legislators, arguing "misguided legislation" has banned apps like Ash "while leaving unregulated chatbots it intended to regulate free to cause harm." A spokesperson for Ash did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Mario Treto Jr., secretary of the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, said the goal was ultimately to make sure licensed therapists were the only ones doing therapy. "Therapy is more than just word exchanges," Treto said. "It requires empathy, it requires clinical judgment, it requires ethical responsibility, none of which AI can truly replicate right now." In March, a Dartmouth College-based team published the first known randomized clinical trial of a generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. The goal was to have the chatbot, called Therabot, treat people diagnosed with anxiety, depression or eating disorders. It was trained on vignettes and transcripts written by the team to illustrate an evidence-based response. The study found users rated Therabot similar to a therapist and had meaningfully lower symptoms after eight weeks compared with people who didn't use it. Every interaction was monitored by a human who intervened if the chatbot's response was harmful or not evidence-based. Nicholas Jacobson, a clinical psychologist whose lab is leading the research, said the results showed early promise but that larger studies are needed to demonstrate whether Therabot works for large numbers of people. "The space is so dramatically new that I think the field needs to proceed with much greater caution that is happening right now," he said. Many AI apps are optimized for engagement and are built to support everything users say, rather than challenging peoples' thoughts the way therapists do. Many walk the line of companionship and therapy, blurring intimacy boundaries therapists ethically would not. The app is still in testing and not widely available. But Jacobson worries about what strict bans will mean for developers taking a careful approach. He noted Illinois had no clear pathway to provide evidence that an app is safe and effective. "They want to protect folks, but the traditional system right now is really failing folks," he said. "So, trying to stick with the status quo is really not the thing to do." Regulators and advocates of the laws say they are open to changes. But today's chatbots are not a solution to the mental health provider shortage, said Kyle Hillman, who lobbied for the bills in Illinois and Nevada through his affiliation with the National Association of Social Workers. "Not everybody who's feeling sad needs a therapist," he said. But for people with real mental health issues or suicidal thoughts, "telling them, 'I know that there's a workforce shortage but here's a bot' -- that is such a privileged position." The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

[4]

Regulators struggle to keep up with the fast-moving and complicated landscape of AI therapy apps

In the absence of stronger federal regulation, some states have begun regulating apps that offer AI "therapy" as more people turn to artificial intelligence for mental health advice. But the laws, all passed this year, don't fully address the fast-changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, policymakers and mental health advocates say the resulting patchwork of state laws isn't enough to protect users or hold the creators of harmful technology accountable. "The reality is millions of people are using these tools and they're not going back," said Karin Andrea Stephan, CEO and co-founder of the mental health chatbot app Earkick. The state laws take different approaches. Illinois and Nevada have banned the use of AI to treat mental health. Utah placed certain limits on therapy chatbots, including requiring them to protect users' health information and to clearly disclose that the chatbot isn't human. Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California are also considering ways to regulate AI therapy. The impact on users varies. Some apps have blocked access in states with bans. Others say they're making no changes as they wait for more legal clarity. And many of the laws don't cover generic chatbots like ChatGPT, which are not explicitly marketed for therapy but are used by an untold number of people for it. Those bots have attracted lawsuits in horrific instances where users lost their grip on reality or took their own lives after interacting with them. Vaile Wright, who oversees health care innovation at the American Psychological Association, agreed that the apps could fill a need, noting a nationwide shortage of mental health providers, high costs for care and uneven access for insured patients. Mental health chatbots that are rooted in science, created with expert input and monitored by humans could change the landscape, Wright said. "This could be something that helps people before they get to crisis," she said. "That's not what's on the commercial market currently." That's why federal regulation and oversight is needed, she said. Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission announced it was opening inquiries into seven AI chatbot companies -- including the parent companies of Instagram and Facebook, Google, ChatGPT, Grok (the chatbot on X), Character.AI and Snapchat -- on how they "measure, test and monitor potentially negative impacts of this technology on children and teens." And the Food and Drug Administration is convening an advisory committee Nov. 6 to review generative AI-enabled mental health devices. Federal agencies could consider restrictions on how chatbots are marketed, limit addictive practices, require disclosures to users that they are not medical providers, require companies to track and report suicidal thoughts, and offer legal protections for people who report bad practices by companies, Wright said. Not all apps have blocked access From "companion apps" to "AI therapists" to "mental wellness" apps, AI's use in mental health care is varied and hard to define, let alone write laws around. That has led to different regulatory approaches. Some states, for example, take aim at companion apps that are designed just for friendship, but don't wade into mental health care. The laws in Illinois and Nevada ban products that claim to provide mental health treatment outright, threatening fines up to $10,000 in Illinois and $15,000 in Nevada. But even a single app can be tough to categorize. Earkick's Stephan said there is still a lot that is "very muddy" about Illinois' law, for example, and the company has not limited access there. Stephan and her team initially held off calling their chatbot, which looks like a cartoon panda, a therapist. But when users began using the word in reviews, they embraced the terminology so the app would show up in searches. Last week, they backed off using therapy and medical terms again. Earkick's website described its chatbot as "Your empathetic AI counselor, equipped to support your mental health journey," but now it's a "chatbot for self care." Still, "we're not diagnosing," Stephan maintained. Users can set up a "panic button" to call a trusted loved one if they are in crisis and the chatbot will "nudge" users to seek out a therapist if their mental health worsens. But it was never designed to be a suicide prevention app, Stephan said, and police would not be called if someone told the bot about thoughts of self-harm. Stephan said she's happy that people are looking at AI with a critical eye, but worried about states' ability to keep up with innovation. "The speed at which everything is evolving is massive," she said. Other apps blocked access immediately. When Illinois users download the AI therapy app Ash, a message urges them to email their legislators, arguing "misguided legislation" has banned apps like Ash "while leaving unregulated chatbots it intended to regulate free to cause harm." A spokesperson for Ash did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Mario Treto Jr., secretary of the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, said the goal was ultimately to make sure licensed therapists were the only ones doing therapy. "Therapy is more than just word exchanges," Treto said. "It requires empathy, it requires clinical judgment, it requires ethical responsibility, none of which AI can truly replicate right now." One chatbot company is trying to fully replicate therapy In March, a Dartmouth University-based team published the first known randomized clinical trial of a generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. The goal was to have the chatbot, called Therabot, treat people diagnosed with anxiety, depression or eating disorders. It was trained on vignettes and transcripts written by the team to illustrate an evidence-based response. The study found users rated Therabot similar to a therapist and had meaningfully lower symptoms after eight weeks compared with people who didn't use it. Every interaction was monitored by a human who intervened if the chatbot's response was harmful or not evidence-based. Nicholas Jacobson, a clinical psychologist whose lab is leading the research, said the results showed early promise but that larger studies are needed to demonstrate whether Therabot works for large numbers of people. "The space is so dramatically new that I think the field needs to proceed with much greater caution that is happening right now," he said. Many AI apps are optimized for engagement and are built to support everything users say, rather than challenging peoples' thoughts the way therapists do. Many walk the line of companionship and therapy, blurring intimacy boundaries therapists ethically would not. Therabot's team sought to avoid those issues. The app is still in testing and not widely available. But Jacobson worries about what strict bans will mean for developers taking a careful approach. He noted Illinois had no clear pathway to provide evidence that an app is safe and effective. "They want to protect folks, but the traditional system right now is really failing folks," he said. "So, trying to stick with the status quo is really not the thing to do." Regulators and advocates of the laws say they are open to changes. But today's chatbots are not a solution to the mental health provider shortage, said Kyle Hillman, who lobbied for the bills in Illinois and Nevada through his affiliation with the National Association of Social Workers. "Not everybody who's feeling sad needs a therapist," he said. But for people with real mental health issues or suicidal thoughts, "telling them, 'I know that there's a workforce shortage but here's a bot' -- that is such a privileged position."

[5]

Regulators struggle to catch up to AI therapy boom

That's why federal regulation and oversight are needed, she said. Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission announced it was opening inquiries into seven AI chatbot companies -- including the parent companies of Instagram and Facebook, Google, ChatGPT, Grok (the chatbot on X), Character.AI and Snapchat -- on how they "measure, test and monitor potentially negative impacts of this technology on children and teens." And the Food and Drug Administration is convening an advisory committee Nov. 6 to review generative AI-enabled mental health devices. Federal agencies could consider restrictions on how chatbots are marketed, limit addictive practices, require disclosures to users that they are not medical providers, require companies to track and report suicidal thoughts, and offer legal protections for people who report bad practices by companies, Wright said. Not all apps have blocked access From "companion apps" to "AI therapists" to "mental wellness" apps, AI's use in mental health care is varied and hard to define, let alone write laws around.

[6]

Regulators struggle to keep up with the fast-moving and complicated landscape of AI therapy apps

In the absence of stronger federal regulation, some states have begun regulating apps that offer AI "therapy" as more people turn to artificial intelligence for mental health advice. But the laws, all passed this year, don't fully address the fast-changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, policymakers and mental health advocates say the resulting patchwork of state laws isn't enough to protect users or hold the creators of harmful technology accountable. "The reality is millions of people are using these tools and they're not going back," said Karin Andrea Stephan, CEO and co-founder of the mental health chatbot app Earkick. ___ EDITOR'S NOTE -- This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org. ___ The state laws take different approaches. Illinois and Nevada have banned the use of AI to treat mental health. Utah placed certain limits on therapy chatbots, including requiring them to protect users' health information and to clearly disclose that the chatbot isn't human. Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California are also considering ways to regulate AI therapy. The impact on users varies. Some apps have blocked access in states with bans. Others say they're making no changes as they wait for more legal clarity. And many of the laws don't cover generic chatbots like ChatGPT, which are not explicitly marketed for therapy but are used by an untold number of people for it. Those bots have attracted lawsuits in horrific instances where users lost their grip on reality or took their own lives after interacting with them. Vaile Wright, who oversees health care innovation at the American Psychological Association, agreed that the apps could fill a need, noting a nationwide shortage of mental health providers, high costs for care and uneven access for insured patients. Mental health chatbots that are rooted in science, created with expert input and monitored by humans could change the landscape, Wright said. "This could be something that helps people before they get to crisis," she said. "That's not what's on the commercial market currently." That's why federal regulation and oversight is needed, she said. Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission announced it was opening inquiries into seven AI chatbot companies -- including the parent companies of Instagram and Facebook, Google, ChatGPT, Grok (the chatbot on X), Character.AI and Snapchat -- on how they "measure, test and monitor potentially negative impacts of this technology on children and teens." And the Food and Drug Administration is convening an advisory committee Nov. 6 to review generative AI-enabled mental health devices. Federal agencies could consider restrictions on how chatbots are marketed, limit addictive practices, require disclosures to users that they are not medical providers, require companies to track and report suicidal thoughts, and offer legal protections for people who report bad practices by companies, Wright said. Not all apps have blocked access From "companion apps" to "AI therapists" to "mental wellness" apps, AI's use in mental health care is varied and hard to define, let alone write laws around. That has led to different regulatory approaches. Some states, for example, take aim at companion apps that are designed just for friendship, but don't wade into mental health care. The laws in Illinois and Nevada ban products that claim to provide mental health treatment outright, threatening fines up to $10,000 in Illinois and $15,000 in Nevada. But even a single app can be tough to categorize. Earkick's Stephan said there is still a lot that is "very muddy" about Illinois' law, for example, and the company has not limited access there. Stephan and her team initially held off calling their chatbot, which looks like a cartoon panda, a therapist. But when users began using the word in reviews, they embraced the terminology so the app would show up in searches. Last week, they backed off using therapy and medical terms again. Earkick's website described its chatbot as "Your empathetic AI counselor, equipped to support your mental health journey," but now it's a "chatbot for self care." Still, "we're not diagnosing," Stephan maintained. Users can set up a "panic button" to call a trusted loved one if they are in crisis and the chatbot will "nudge" users to seek out a therapist if their mental health worsens. But it was never designed to be a suicide prevention app, Stephan said, and police would not be called if someone told the bot about thoughts of self-harm. Stephan said she's happy that people are looking at AI with a critical eye, but worried about states' ability to keep up with innovation. "The speed at which everything is evolving is massive," she said. Other apps blocked access immediately. When Illinois users download the AI therapy app Ash, a message urges them to email their legislators, arguing "misguided legislation" has banned apps like Ash "while leaving unregulated chatbots it intended to regulate free to cause harm." A spokesperson for Ash did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Mario Treto Jr., secretary of the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, said the goal was ultimately to make sure licensed therapists were the only ones doing therapy. "Therapy is more than just word exchanges," Treto said. "It requires empathy, it requires clinical judgment, it requires ethical responsibility, none of which AI can truly replicate right now." One chatbot company is trying to fully replicate therapy In March, a Dartmouth University-based team published the first known randomized clinical trial of a generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. The goal was to have the chatbot, called Therabot, treat people diagnosed with anxiety, depression or eating disorders. It was trained on vignettes and transcripts written by the team to illustrate an evidence-based response. The study found users rated Therabot similar to a therapist and had meaningfully lower symptoms after eight weeks compared with people who didn't use it. Every interaction was monitored by a human who intervened if the chatbot's response was harmful or not evidence-based. Nicholas Jacobson, a clinical psychologist whose lab is leading the research, said the results showed early promise but that larger studies are needed to demonstrate whether Therabot works for large numbers of people. "The space is so dramatically new that I think the field needs to proceed with much greater caution that is happening right now," he said. Many AI apps are optimized for engagement and are built to support everything users say, rather than challenging peoples' thoughts the way therapists do. Many walk the line of companionship and therapy, blurring intimacy boundaries therapists ethically would not. Therabot's team sought to avoid those issues. The app is still in testing and not widely available. But Jacobson worries about what strict bans will mean for developers taking a careful approach. He noted Illinois had no clear pathway to provide evidence that an app is safe and effective. "They want to protect folks, but the traditional system right now is really failing folks," he said. "So, trying to stick with the status quo is really not the thing to do." Regulators and advocates of the laws say they are open to changes. But today's chatbots are not a solution to the mental health provider shortage, said Kyle Hillman, who lobbied for the bills in Illinois and Nevada through his affiliation with the National Association of Social Workers. "Not everybody who's feeling sad needs a therapist," he said. But for people with real mental health issues or suicidal thoughts, "telling them, 'I know that there's a workforce shortage but here's a bot' -- that is such a privileged position." ___ The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

[7]

Regulators struggle to keep up with the fast-moving AI

As mental health chatbots driven by artificial intelligence proliferate, a small number of states are trying to regulate them In the absence of stronger federal regulation, some states have begun regulating apps that offer AI "therapy" as more people turn to artificial intelligence for mental health advice. But the laws, all passed this year, don't fully address the fast-changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, policymakers and mental health advocates say the resulting patchwork of state laws isn't enough to protect users or hold the creators of harmful technology accountable. "The reality is millions of people are using these tools and they're not going back," said Karin Andrea Stephan, CEO and co-founder of the mental health chatbot app Earkick. ___ EDITOR'S NOTE -- This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org. ___ The state laws take different approaches. Illinois and Nevada have banned the use of AI to treat mental health. Utah placed certain limits on therapy chatbots, including requiring them to protect users' health information and to clearly disclose that the chatbot isn't human. Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California are also considering ways to regulate AI therapy. The impact on users varies. Some apps have blocked access in states with bans. Others say they're making no changes as they wait for more legal clarity. And many of the laws don't cover generic chatbots like ChatGPT, which are not explicitly marketed for therapy but are used by an untold number of people for it. Those bots have attracted lawsuits in horrific instances where users lost their grip on reality or took their own lives after interacting with them. Vaile Wright, who oversees health care innovation at the American Psychological Association, agreed that the apps could fill a need, noting a nationwide shortage of mental health providers, high costs for care and uneven access for insured patients. Mental health chatbots that are rooted in science, created with expert input and monitored by humans could change the landscape, Wright said. "This could be something that helps people before they get to crisis," she said. "That's not what's on the commercial market currently." That's why federal regulation and oversight is needed, she said. Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission announced it was opening inquiries into seven AI chatbot companies -- including the parent companies of Instagram and Facebook, Google, ChatGPT, Grok (the chatbot on X), Character.AI and Snapchat -- on how they "measure, test and monitor potentially negative impacts of this technology on children and teens." And the Food and Drug Administration is convening an advisory committee Nov. 6 to review generative AI-enabled mental health devices. Federal agencies could consider restrictions on how chatbots are marketed, limit addictive practices, require disclosures to users that they are not medical providers, require companies to track and report suicidal thoughts, and offer legal protections for people who report bad practices by companies, Wright said. From "companion apps" to "AI therapists" to "mental wellness" apps, AI's use in mental health care is varied and hard to define, let alone write laws around. That has led to different regulatory approaches. Some states, for example, take aim at companion apps that are designed just for friendship, but don't wade into mental health care. The laws in Illinois and Nevada ban products that claim to provide mental health treatment outright, threatening fines up to $10,000 in Illinois and $15,000 in Nevada. But even a single app can be tough to categorize. Earkick's Stephan said there is still a lot that is "very muddy" about Illinois' law, for example, and the company has not limited access there. Stephan and her team initially held off calling their chatbot, which looks like a cartoon panda, a therapist. But when users began using the word in reviews, they embraced the terminology so the app would show up in searches. Last week, they backed off using therapy and medical terms again. Earkick's website described its chatbot as "Your empathetic AI counselor, equipped to support your mental health journey," but now it's a "chatbot for self care." Still, "we're not diagnosing," Stephan maintained. Users can set up a "panic button" to call a trusted loved one if they are in crisis and the chatbot will "nudge" users to seek out a therapist if their mental health worsens. But it was never designed to be a suicide prevention app, Stephan said, and police would not be called if someone told the bot about thoughts of self-harm. Stephan said she's happy that people are looking at AI with a critical eye, but worried about states' ability to keep up with innovation. "The speed at which everything is evolving is massive," she said. Other apps blocked access immediately. When Illinois users download the AI therapy app Ash, a message urges them to email their legislators, arguing "misguided legislation" has banned apps like Ash "while leaving unregulated chatbots it intended to regulate free to cause harm." A spokesperson for Ash did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Mario Treto Jr., secretary of the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, said the goal was ultimately to make sure licensed therapists were the only ones doing therapy. "Therapy is more than just word exchanges," Treto said. "It requires empathy, it requires clinical judgment, it requires ethical responsibility, none of which AI can truly replicate right now." In March, a Dartmouth University-based team published the first known randomized clinical trial of a generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. The goal was to have the chatbot, called Therabot, treat people diagnosed with anxiety, depression or eating disorders. It was trained on vignettes and transcripts written by the team to illustrate an evidence-based response. The study found users rated Therabot similar to a therapist and had meaningfully lower symptoms after eight weeks compared with people who didn't use it. Every interaction was monitored by a human who intervened if the chatbot's response was harmful or not evidence-based. Nicholas Jacobson, a clinical psychologist whose lab is leading the research, said the results showed early promise but that larger studies are needed to demonstrate whether Therabot works for large numbers of people. "The space is so dramatically new that I think the field needs to proceed with much greater caution that is happening right now," he said. Many AI apps are optimized for engagement and are built to support everything users say, rather than challenging peoples' thoughts the way therapists do. Many walk the line of companionship and therapy, blurring intimacy boundaries therapists ethically would not. Therabot's team sought to avoid those issues. The app is still in testing and not widely available. But Jacobson worries about what strict bans will mean for developers taking a careful approach. He noted Illinois had no clear pathway to provide evidence that an app is safe and effective. "They want to protect folks, but the traditional system right now is really failing folks," he said. "So, trying to stick with the status quo is really not the thing to do." Regulators and advocates of the laws say they are open to changes. But today's chatbots are not a solution to the mental health provider shortage, said Kyle Hillman, who lobbied for the bills in Illinois and Nevada through his affiliation with the National Association of Social Workers. "Not everybody who's feeling sad needs a therapist," he said. But for people with real mental health issues or suicidal thoughts, "telling them, 'I know that there's a workforce shortage but here's a bot' -- that is such a privileged position." ___ The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

[8]

Regulators Struggle to Keep up With the Fast-Moving and Complicated Landscape of AI Therapy Apps

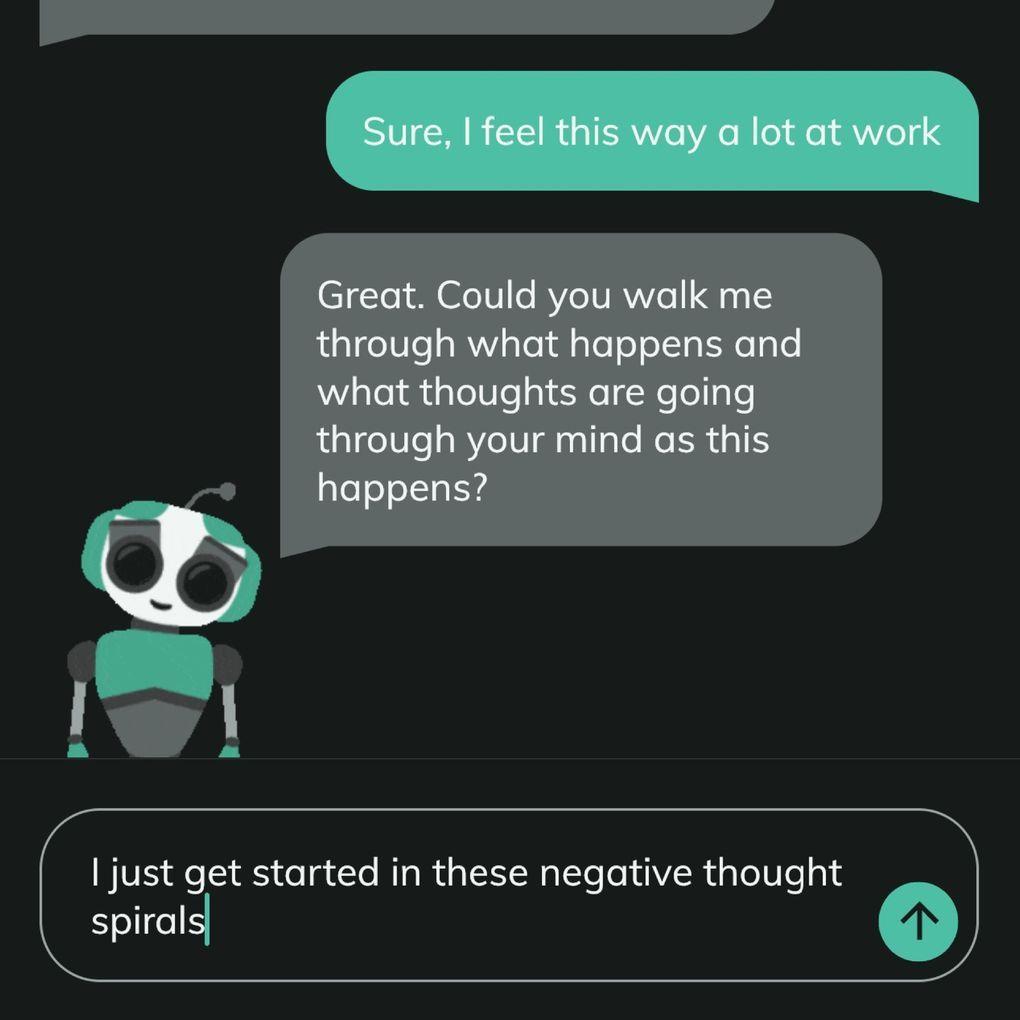

This image provided by Dartmouth in September 2025, depicts a text message exchange with the Therabot generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. (Michael Heinz, Nicholas Jacobson/Dartmouth via AP) In the absence of stronger federal regulation, some states have begun regulating apps that offer AI "therapy" as more people turn to artificial intelligence for mental health advice. But the laws, all passed this year, don't fully address the fast-changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, policymakers and mental health advocates say the resulting patchwork of state laws isn't enough to protect users or hold the creators of harmful technology accountable. "The reality is millions of people are using these tools and they're not going back," said Karin Andrea Stephan, CEO and co-founder of the mental health chatbot app Earkick. ___ EDITOR'S NOTE -- This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org. ___ The state laws take different approaches. Illinois and Nevada have banned the use of AI to treat mental health. Utah placed certain limits on therapy chatbots, including requiring them to protect users' health information and to clearly disclose that the chatbot isn't human. Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California are also considering ways to regulate AI therapy. The impact on users varies. Some apps have blocked access in states with bans. Others say they're making no changes as they wait for more legal clarity. And many of the laws don't cover generic chatbots like ChatGPT, which are not explicitly marketed for therapy but are used by an untold number of people for it. Those bots have attracted lawsuits in horrific instances where users lost their grip on reality or took their own lives after interacting with them. Vaile Wright, who oversees health care innovation at the American Psychological Association, agreed that the apps could fill a need, noting a nationwide shortage of mental health providers, high costs for care and uneven access for insured patients. Mental health chatbots that are rooted in science, created with expert input and monitored by humans could change the landscape, Wright said. "This could be something that helps people before they get to crisis," she said. "That's not what's on the commercial market currently." That's why federal regulation and oversight is needed, she said. Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission announced it was opening inquiries into seven AI chatbot companies -- including the parent companies of Instagram and Facebook, Google, ChatGPT, Grok (the chatbot on X), Character.AI and Snapchat -- on how they "measure, test and monitor potentially negative impacts of this technology on children and teens." And the Food and Drug Administration is convening an advisory committee Nov. 6 to review generative AI-enabled mental health devices. Federal agencies could consider restrictions on how chatbots are marketed, limit addictive practices, require disclosures to users that they are not medical providers, require companies to track and report suicidal thoughts, and offer legal protections for people who report bad practices by companies, Wright said. Not all apps have blocked access From "companion apps" to "AI therapists" to "mental wellness" apps, AI's use in mental health care is varied and hard to define, let alone write laws around. That has led to different regulatory approaches. Some states, for example, take aim at companion apps that are designed just for friendship, but don't wade into mental health care. The laws in Illinois and Nevada ban products that claim to provide mental health treatment outright, threatening fines up to $10,000 in Illinois and $15,000 in Nevada. But even a single app can be tough to categorize. Earkick's Stephan said there is still a lot that is "very muddy" about Illinois' law, for example, and the company has not limited access there. Stephan and her team initially held off calling their chatbot, which looks like a cartoon panda, a therapist. But when users began using the word in reviews, they embraced the terminology so the app would show up in searches. Last week, they backed off using therapy and medical terms again. Earkick's website described its chatbot as "Your empathetic AI counselor, equipped to support your mental health journey," but now it's a "chatbot for self care." Still, "we're not diagnosing," Stephan maintained. Users can set up a "panic button" to call a trusted loved one if they are in crisis and the chatbot will "nudge" users to seek out a therapist if their mental health worsens. But it was never designed to be a suicide prevention app, Stephan said, and police would not be called if someone told the bot about thoughts of self-harm. Stephan said she's happy that people are looking at AI with a critical eye, but worried about states' ability to keep up with innovation. "The speed at which everything is evolving is massive," she said. Other apps blocked access immediately. When Illinois users download the AI therapy app Ash, a message urges them to email their legislators, arguing "misguided legislation" has banned apps like Ash "while leaving unregulated chatbots it intended to regulate free to cause harm." A spokesperson for Ash did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Mario Treto Jr., secretary of the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, said the goal was ultimately to make sure licensed therapists were the only ones doing therapy. "Therapy is more than just word exchanges," Treto said. "It requires empathy, it requires clinical judgment, it requires ethical responsibility, none of which AI can truly replicate right now." One chatbot company is trying to fully replicate therapy In March, a Dartmouth University-based team published the first known randomized clinical trial of a generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. The goal was to have the chatbot, called Therabot, treat people diagnosed with anxiety, depression or eating disorders. It was trained on vignettes and transcripts written by the team to illustrate an evidence-based response. The study found users rated Therabot similar to a therapist and had meaningfully lower symptoms after eight weeks compared with people who didn't use it. Every interaction was monitored by a human who intervened if the chatbot's response was harmful or not evidence-based. Nicholas Jacobson, a clinical psychologist whose lab is leading the research, said the results showed early promise but that larger studies are needed to demonstrate whether Therabot works for large numbers of people. "The space is so dramatically new that I think the field needs to proceed with much greater caution that is happening right now," he said. Many AI apps are optimized for engagement and are built to support everything users say, rather than challenging peoples' thoughts the way therapists do. Many walk the line of companionship and therapy, blurring intimacy boundaries therapists ethically would not. Therabot's team sought to avoid those issues. The app is still in testing and not widely available. But Jacobson worries about what strict bans will mean for developers taking a careful approach. He noted Illinois had no clear pathway to provide evidence that an app is safe and effective. "They want to protect folks, but the traditional system right now is really failing folks," he said. "So, trying to stick with the status quo is really not the thing to do." Regulators and advocates of the laws say they are open to changes. But today's chatbots are not a solution to the mental health provider shortage, said Kyle Hillman, who lobbied for the bills in Illinois and Nevada through his affiliation with the National Association of Social Workers. "Not everybody who's feeling sad needs a therapist," he said. But for people with real mental health issues or suicidal thoughts, "telling them, 'I know that there's a workforce shortage but here's a bot' -- that is such a privileged position." ___ The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Share

Share

Copy Link

As AI chatbots increasingly offer mental health support, regulators struggle to keep pace with the rapidly evolving landscape. Experts warn of potential risks and call for stronger federal oversight.

The Rise of AI Mental Health Support

In recent years, the landscape of mental health support has been rapidly evolving with the introduction of AI-powered chatbots and virtual therapists. These tools, ranging from general-purpose chatbots to specialized mental health apps, have gained significant traction among users seeking accessible and immediate support

1

2

.

Source: CNET

Concerns and Risks

However, mental health professionals and consumer advocates have raised serious concerns about the use of AI for therapy. Researchers from several universities found that AI chatbots are not safe replacements for human therapists, often providing low-quality therapeutic support

1

. There have been alarming instances where chatbots encouraged self-harm, suicide, or substance abuse relapse1

.Regulatory Challenges

The rapid development of AI therapy tools has left regulators struggling to keep pace. Several states have taken action, with Illinois and Nevada banning the use of AI for mental health treatment, while Utah has imposed certain limitations on therapy chatbots

2

3

. However, this patchwork of state laws is insufficient to address the complex and fast-moving landscape of AI in mental health care4

.

Source: Fast Company

Federal Oversight and Investigations

Recognizing the need for broader regulation, federal agencies have begun to take action. The Federal Trade Commission has launched inquiries into seven major AI chatbot companies, including Meta, Google, and OpenAI, to investigate potential negative impacts on children and teens

2

5

. The Food and Drug Administration is also reviewing generative AI-enabled mental health devices2

.Related Stories

The Industry's Response

AI therapy app developers are grappling with the evolving regulatory environment. Some, like Earkick, have adjusted their marketing language to avoid medical terminology, while others have blocked access in states with bans

3

. The industry acknowledges the need for oversight but expresses concern about the ability of state-level regulations to keep up with rapid technological advancements3

.Future Outlook

Experts suggest that AI could potentially fill gaps in mental health care, given the shortage of providers and high costs of traditional therapy

2

. However, they emphasize the need for AI tools to be rooted in science, created with expert input, and monitored by humans2

. As the field continues to evolve, the challenge remains to balance innovation with user safety and effective mental health support.

Source: Seattle Times

References

Summarized by

Navi

[2]

[4]

[5]

Related Stories

AI Chatbots as Therapists: Potential Benefits and Serious Risks Revealed in Stanford Study

09 Jul 2025•Technology

AI Therapy: Promising Potential and Ethical Concerns in Mental Health Care

05 May 2025•Health

AI Therapy Chatbot Shows Promise in First Clinical Trial for Depression and Anxiety

28 Mar 2025•Health

Recent Highlights

1

Google Gemini 3.1 Pro doubles reasoning score, beats rivals in key AI benchmarks

Technology

2

Nvidia and Meta forge massive chip deal as computing power demands reshape AI infrastructure

Technology

3

ChatGPT cracks decades-old gluon amplitude puzzle, marking AI's first major theoretical physics win

Science and Research